On August 23, 1939, the romance of American communism collided with the realpolitik of the Soviet Union. Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin had come to an arrangement. In Moscow, Nazi foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop and Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov signed a mutual nonaggression pact that carved up Poland, surrendered Finland, and lit the fuse for a European war. Flashed worldwide by wire photo, pictures of the cozy diplomatic scene struck like a lightning bolt—or, to the staunch anti-Nazi, a knife in the heart.

In America, literally overnight, the Hitler-Stalin Pact fractured the sense of common purpose that had unified the disparate ranks of the Popular Front. Heeding marching orders from the Comintern, the Moscow-based nerve center for revolutionary action, American communists pledged fealty to the hastily revised party line. Stupefied by the betrayal, liberals bolted from the new orthodoxy.1 At the 1939–40 New York World’s Fair, the film programming at the Russian Pavilion reacted to the seismic shift in the geopolitical terrain. The Soviet-made anti-Nazi film Professor Mamlock (1938) was yanked from the screen and replaced with Lenin in 1918 (1939), a hagiographic biopic binding the founder of the Soviet state to his strong right arm and anointed successor, Joseph Stalin. “Just a routine change of program,” insisted Soviet officials.2

Many Popular Front groups were also forced to change their programs. Few fell into line as compliantly as the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League. With the selfsame fervor lately mustered to oppose Nazism, HANL now opposed the policies it had once advocated so passionately—a peacetime draft, a strong national defense, and American intervention in European affairs. “The League affirms positively that the United States should in no way become involved in the war,” editorialized Hollywood Now, as the Luftwaffe strafed Poland.3 Even the party liners found it hard to look former allies in the eye and defend the 180-degree turnabout with a straight face. “I didn’t think myself into an acceptance of the pact as much as I felt that there must be a reason for it,” Donald Ogden Stewart reflected years later. “Russia was the only country of Marxism, and I didn’t think I could abandon Stalin without surrendering my life raft.”4

On December 15, 1939, the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League dropped the “anti-Nazi” from its masthead and officially changed its name to the Hollywood League for Democratic Action. In context, “democratic action” meant isolationist paralysis.

In January 1940, with Poland crushed but “brave little Finland” still hanging on against Soviet aggression, the renamed League launched a “vigorous protest against loans to Finland or other belligerents” and passed a resolution affirming same. “The Hollywood League for Democratic Action composed of 4,000 members, wishes to go on record as unalterably opposed” to financial aid to Finland or other warring nations—notably France or Great Britain—as “a flagrant evasion of that neutrality which the administration has pledged the American people.” Making common cause with Republican Party isolationists, the League declared: “These bills violate the spirit and essence of our neutrality by involving America in European affairs. Such loans will endanger the peace of this nation.”5

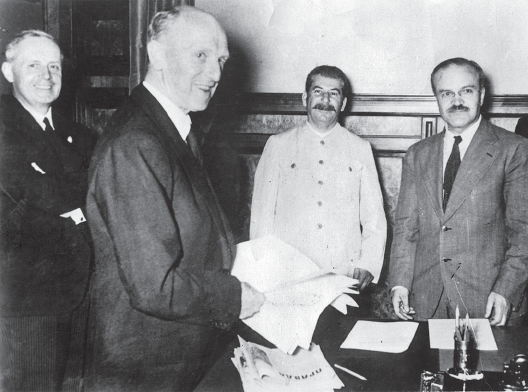

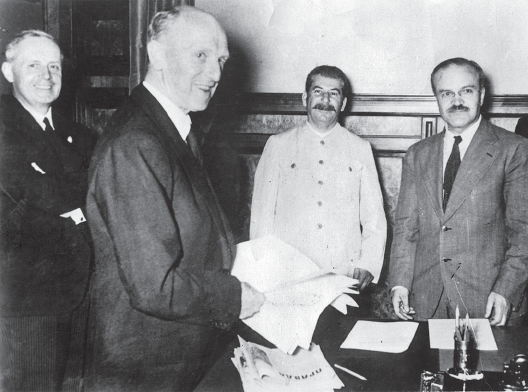

Shattering the Popular Front (left to right): in Moscow, German foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop, German undersecretary of state Dr. Friedrich Wilhelm Gaus, a beaming Josef Stalin, and Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov, at the signing of the Soviet-German Non-Aggression Pact, August 23, 1939.

By then, Hollywood’s red-blooded political action group had become an anemic shell of its former self. While Stewart and his comrades clung to their life raft, the liberals who had swelled the ranks of the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League leapt overboard. Membership shrank and donations dried up. Soon, the executive officers were reduced to pleading for basic operating funds. “This issue [of Hollywood Now] will reach you after a hectic week during which our staff set aside important work in order to try to raise enough money to make a small payment to the printer,” the League informed its dwindling readership. “The crisis isn’t over—not by a long shot. If you want to see Hollywood Now continue in business, you must furnish it with the necessary money. We put this bluntly because that’s the way things shape up.”6

Only party discipline and an eye for the big picture kept the true believers in line. The screenwriter Dalton Trumbo, a dutiful party liner, published an anitwar novel, Johnny Got His Gun, about a young American doughboy from the Great War, his face, arms, and legs blown off, who pleads in Morse code to be put on exhibit as a warning to future generations.7 A belated variation on All Quiet on the Western Front, the tract was designed to remind readers of the horror and waste of the Great War. Americans who argued for defense appropriations and intervention overseas, Trumbo declared, held opinions that “constitute a treasonable state of mind.”8

Of course, the new party line followed by the League also applied to Hollywood feature films. Apparently, the Hays office had been right all along: interventionist themes and anti-Nazi plotlines had no place in American motion picture entertainment. Like Washington, Hollywood should butt out of European affairs.

Ironically, however, even as the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League was parroting Soviet foreign policy, the major studios had been roused to action. In the 1939–1941 interim between the Hitler-Stalin Pact and the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, a slate of unabashedly anti-Nazi melodramas moved through the studio pipelines—works that kindled a revived American patriotism, that called for a strong national defense, and that named Germany as the wolf at the door. Hollywood was finally making the kind of films that the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League had been demanding since 1936—only now the rebranded League was no longer in the business of anti-Nazism.

Hollywood, however, had decided anti-Nazism was indeed its business. Even the most conservative moguls were not insensitive to the shift in the zeitgeist—that with the outbreak of war in Europe, a nation of isolationist temper could also be pro-defense and anti-Nazi. True to industry form, a decisive factor in the sensibility turnabout was commercial. The considerations that had constrained Hollywood since 1933—the profits from the German market and the hope that relations might return to normal in a post-Hitler Germany—had become moot. Hollywood made anti-Nazi films because, after September 1939, there was no good reason not to.

On September 1, 1939, when war broke out in Europe, Hollywood’s first concern was the futures market—namely, how the fighting would impact box office revenues from overseas. The major studios took in around a third of their total profits from foreign markets, with 17 percent of the revenue stream drawn from England, France, and Poland, at the time the major belligerents. Optimistically—too optimistically as it turned out—the projected shortfall from the warring nations was estimated to be a mere 25 percent of the peacetime take.a A trade analysis indicated that the Axis powers had already been written off as profit centers. “Germany, of course, has long since been deemed a lost market for U.S. films, save for skeleton organizations maintained by Metro, 20th-Fox, and Paramount. For another reason, all the majors bowed out en masse from Italy Jan. 1 [1939].”9 (On that date, Mussolini nationalized all aspects of the Italian film industry, including the business of foreign distribution, precipitating a total American withdrawal.) Fixated on the ticket window, Variety was not fretting over the fate of Poland. “Outbreak of European war would be a blow to American picture distribution in the foreign field,” it lamented. “Greatest threat to profitable operations in warring countries would be the clamping down on coin restrictions.”10

Motion picture personnel in Nazi-occupied Europe faced greater threats than blocked currency. From the safety of Paris, Boris Jankolowicz, head of the Warner Bros. branch office in Warsaw, sent back a ghastly account of how seriously the Nazis took cinema. Jankolowicz had trekked over 300 miles “with only the clothes on his back and a few scraps of food” to escape the Nazi blitzkrieg. He reported that Polish exhibitors who had screened Confessions of a Nazi Spy (1939) were hanged from the rafters of their own theaters.11

On the domestic front, before the booming economy of the war years pumped up weekly attendance figures to 85–90 million moviegoers per week, Hollywood’s audience was diverted by the real-life drama purveyed by another medium. With the news from Europe surpassing the danger and suspense of any scenario on screen, many Americans spent evenings huddled by their radios rather than at the corner Bijou. The war of the worlds was being broadcast for real.

Defying the turn to the radio dial, one motion picture theater boasted a full house—the Embassy Newsreel Theater. Audiences flocked to the Times Square landmark to catch a glimpse of what they had heard over the air and read about in the newspapers. Even dated library shots showing war preparations filmed days or weeks earlier braced jittery patrons. Watching a newsreel while the war overseas raged was “much more dramatic and intense,” Variety felt. “That’s visible in the drawn expressions of the people in the film as well as the bated reception by the newsreel audience.” In late 1939, a lengthy segment in MGM’s News of the Day recapped the events that had led up to the war, including the Munich Crisis of September 1938, when war was averted by the appeasement of British prime minister Neville Chamberlain and French prime minister Édouard Daladier. The newsreel flashed the shot of Chamberlain deplaning at Heston Airport, clutching the white piece of paper that guaranteed “peace in our time.” Throughout World War II, and ever after, the image of the frail old man waving the treaty paper like a flag of surrender would be photographic metonomy for how Europe’s weak-willed democracies cowered before the Nazi war machine. That afternoon at the Embassy marked the first time that audiences viewed the clip with rueful, retrospective knowledge, the first time that the bitter epithet “Munich” became a codeword for appeasement. “It draws hollow laughter in light of current events,” reported Variety.12

What might be thought of as the anti-Embassy—the pro-Nazi Yorkville Theatre, rechristened the 96th Street Theatre, after its cross-street—continued to operate, catering to a German clientele fired up by Nazi military victories across Europe. Benefiting from a surge in pan-German patriotism, the theater initially underwent a spurt in attendance and a concurrent upswing in picket lines. With a collection box for “German War Relief” placed conspicuously in the theater lobby, Nazi propaganda films such as Sieg im Westen (1940), a newsreel celebration of the blitzkrieg into Poland, and D III 88: The German Air Force Attacks (1940), a male-bonding aviation melodrama, made up some of the war-minded entertainment programming. Newsreel shots of Hitler and the swastika inspired “wild cheering” reported an unbylined firsthand account in Variety that must have been written by Wolfe Kaufman given the droll comment that followed: that a crowd cheering Hitler in New York was “slightly amazing within a mile of 100 spots where Adolf would be slung from a lamppost before he could mutter ‘Lebensraum.’”13 The 96th Street Theatre and its programming were shuttered after American entry into World War II.b

In this atmosphere, the precedent of Confessions of a Nazi Spy seemed to open a door that had long been shut in the face of a producer who had been pitching an anti-Nazi melodrama since 1933. Sensing his moment was finally at hand, the ever hopeful Al Rosen sought to breathe new life into his dormant scenario. “Hollywood’s celluloid problem child, the long-projected and comparably long-deterred filming of The Mad Dog of Europe, again is occupying the limelight,” reported Box Office, days after the release of the pathbreaker from Warner Bros. Daily Variety chimed in with a canine pun: “Rosen’s ‘Dog’ Rebarks.”14

Attempting to revive his pet project in a more propitious business climate, Rosen did what he always did—hyped the production in press interviews, met with investors, and secured endorsements from religious leaders. “Al Rosen Announces the Forthcoming Production of The Mad Dog of Europe,” promised his latest round of trade press ads. “[It has been] endorsed by outstanding Catholic periodicals whose editors have read the shooting script, and carefully planned for the past four years, with the keen intuitive ability he has demonstrated in the past.” The updated shooting script remained credited to Herman J. Mankiewicz and Lynn Root, but Rosen now took a screenwriting credit as well. The would-be film was still described as “dealing with true conditions in Germany under Hitler rule,” buttressed by 3,000 feet of newsreel film purporting to show concentration camps and street riots.15

Despite Rosen’s keen opportunism, he was shut out again—or rather beaten to the punch. Producers Distributing Corporation, a bargain-basement outfit hardscrabble even by Poverty Row standards, churned out an anti-Nazi exploitation picture entitled Hitler—Beast of Berlin (1939) and rushed it into theaters by November. Variety panned its artistic merits (“There are doubtless powerful pictures to be made on the anti-Nazi theme, but this isn’t one”) while hailing its commercial acumen (“From a monetary standpoint, this picture should be a spectacular success.… Its treatment is precisely the sort calculated to inflame mob passions during a period of growing hysteria.”).16 Rosen must have gritted his teeth as he followed the grosses and read the tagline for the film that now made The Mad Dog of Europe redundant: “The Mad Monster of Europe Is Loose!” Unfortunately for Rosen, it was not he who released it.

Though less rabid than either Hitler—Beast of Berlin or the aborted Mad Dog of Europe, the anti-Nazi feature films released by the major studios in the interregnum between September 1, 1939, and December 7, 1941, were no less forthright in their condemnation of Nazism. The most devastating of the shots was fired by a filmmaker with good reason to take Nazism—and its führer—personally. In gestation officially since 1937 and probably since 1933, Charles Chaplin’s The Great Dictator (1940) had the great comedian playing his evil doppelgänger for laughs, but not just for laughs, in a dual role as a Jewish barber and a megalomaniacal tyrant. For the first time on screen, the actor spoke fluent English in an end-reel tirade against all that Nazism stood for. (Reflecting the change in MPPDA policy and his esteem for the comic genius, Chaplin’s anti-Nazi film was cheered on by Joseph Breen himself.) Also taking advantage of the new atmosphere, Walter Wanger finally made Personal History, Vincent Sheean’s memoir of the Spanish Civil War, transferring the action to Europe and the London blitz for Alfred Hitchcock’s Foreign Correspondent (1940).

Having already led the charge with Confessions of a Nazi Spy, Warner Bros. kept mostly in the back of the field. Jack Warner made good on his promise to produce Underground (1940), a Berlin-set thriller about German resistance to the Nazis, but where Confessions of a Nazi Spy was a class A production with a massive publicity campaign, Underground was a B-level programmer given a lackluster rollout. The contemplated project about the life of the heroic Protestant pastor Martin Niemöller never came to fruition. Taking the lesson from Juarez (1939), the studio preferred allegorical attacks to another frontal assault on Nazism.

In fact, the two most effective anti-Nazi features from Warner Bros. released before America’s entry into World War II were set during World War I. Both William Keighley’s The Fighting 69th (1940) and Howard Hawks’s Sergeant York (1941) blotted out the antiwar legacy of the interwar Great War films and restored America’s crusade Over There to the status of a patriotic cause worth fighting for in the run-up to the sequel. Accompanying the Great War revisionism were pointed lessons in ethnic and religious tolerance. In The Fighting 69th, after a Jewish recruit changes his name to join the fabled Irish Catholic regiment, a Catholic chaplain returns the favor by filling in for a Jewish rabbi, reading a prayer in Hebrew for the dying Jewish doughboy. For its part, Sergeant York abided no conscientious objection to war in a conversion narrative affirming that a born-again Christian could reconcile faith and patriotism by rendering unto Caesar what is Caesar’s and unto God what is God’s. Backdating the anti-Nazi allegory even further, the Errol Flynn swashbuckler The Sea Hawk (1940) cast Warner Bros.’ most valuable star property as a dashing privateer for Queen Elizabeth, dueling against the expansionist, totalitarian forces of the Hitlerian Spanish monarch Charles I on behalf of plucky, besieged, and freedom-loving England.

Oddly enough, the most affecting of the prewar anti-Nazi films came not from Warner Bros. but from MGM, the studio most deeply immersed in trafficking with the Nazis during the 1930s. Directed by Frank Borzage, who helped ensure that Three Comrades would have no reference at all to the nascent Nazism in the Weimar Republic, The Mortal Storm (1940) reviewed the history of the period between 1933 and 1939 that had been mainly overlooked by the Hollywood cinema produced between 1933 and 1939. The first-act curtain raises on the fateful date of January 30, 1933, a day of some significance and as yet no irony to the beloved Professor Viktor Roth (avuncular character actor Frank Morgan), the personification of bewhiskered Teutonic scholarship, an educator with none of the stuffiness or foibles of Emil Jannings in The Blue Angel (1929) and all of the brilliance and kindheartedness of Semyon Mezhinsky in Professor Mamlock. By screenwriterly coincidence, January 30th is Herr Professor’s sixtieth birthday: telegrams of congratulation pour in from afar, a testament to the universal esteem in which he is held. That night, around the dinner table with friends and family, Professor Roth basks in the glow of a happy home and warm hearth, the well-earned reward of a life devoted to “tolerance and good humor.”

The fete is interrupted by a maid with a momentous bulletin from the radio. “Something wonderful has happened! We have just heard. They have made Adolf Hitler chancellor of Germany!” she blurts, giddy with excitement.

Germany’s slide into oppression is not incremental. As a gemütlich German town is swathed in the regalia of Nazism, the university, once a citadel of learning, morphs into a military camp. A phalanx of thuggish student-brownshirts sits menacingly in the lecture hall and shouts down Professor Roth when he affirms the biochemical unity of all bloodstreams. A reenactment of the Nazi book burning of May 10, 1933, shows cartloads of books consigned to the fire. Illuminated by tongues of flame, Roth watches as the treasures of German culture—Heinrich Heine, Albert Einstein, Erich Maria Remarque—are torched like so much kindling. Nazism blankets the land, enveloping all, smothering dissent. When peer pressure does not coerce conformity, a boot in the face will serve. For recreation, brownshirts pummel a gentle, kind-hearted family friend named Mr. Werner.

Meanwhile the contagion spreads to Roth’s own home. Under director Borzage’s expert hand, the convivial bustle of the opening sequences is peeled away by degrees, the joyous voices silenced, the social contacts curtailed. The now deserted Roth house resembles a mausoleum. It is as if the cozy neighborhood sheltering the Hardys, MGM’s ur-American family, had been wiped out by a plague.

Unapologetic message mongering: led by former star pupil Fritz Marberg (Robert Young), brownshirts take over the classroom of kindly Professor Roth (Frank Morgan) in MGM’s interwar anti-Nazi film The Mortal Storm (1940).

The word that is still unspoken in The Mortal Storm is “Jew,” but by 1940 only the dimmest moviegoer would have failed to read the signs. The name, physiognomy, and accent of the beaten Mr. Werner mark him for what he is. Professor Roth identifies himself as “non-Aryan” and what kind of non-Aryan is made clear when his wife visits him in a concentration camp and a “J” adorns his sleeve. The Mortal Storm sailed through the Breen office.

After the thunderbolt of the Hitler-Stalin Pact, another vertiginous news bulletin rescrambled the domestic political scene when, on June 22, 1941, Nazi Germany betrayed its cosignatory and invaded the Soviet Union. Immediately, American communists reversed their earlier reversal and took up an anti-Nazi, pro-interventionist stance with renewed vigor. While driving through Connecticut, Donald Ogden Stewart heard a radio announcer read the news and burst into tears—not out of sympathy with the Russian people but out of relief. “I was once more on the ‘right’ side, the side of all my old friends,” he recalled. “I could continue believing in my remote dream, the country where the true equality of man was becoming a reality under the philosophy of Marxism and Leninism and the leadership of the great Stalin.”17 With the Nazis again a common ideological enemy and soon a military one, a wartime version of the Popular Front reassembled and congealed, but the liberals remembered where the real allegiances of their comrades would always reside.

By September 1941, Hollywood’s explicitly anti-Nazi and implicitly pro-interventionist stance had incited a reaction from isolationist elements within the U.S. Senate.c Alarmed at Hollywood’s polemicist streak, a subcommittee of the Senate Interstate Commerce Committee, under the chairmanship of D. Worth Clark (D-ID) and the instigation of Burton Wheeler (D-MT) and Gerald Nye (D-ND), launched a series of hearings into alleged Hollywood war mongering. “The movies control one of the most important sources of information the people have,” declared Senator Clark. “We should ascertain whether they are being used to deluge the people with propaganda tending to incite war.”18 The conversation of the senators, both on the senate floor and in public forums, was tinged with enough nativist antisemitism to justify comparisons with the regime the industry under investigation was condemning on screen. Senator Nye in particular was given to outbursts against “foreign born” persons “of the Jewish faith” plotting to sucker America into another European war.19 To defend itself, the industry hired the highest profile of establishment lawyers—Wendell Willkie, the Republican nominee for president in 1940.

In the course of the widely publicized hearings, Willkie and the moguls routed the senators. In passionate testimony, a defiant Darryl F. Zanuck of Twentieth Century-Fox spoke for his colleagues: yes, Hollywood was making anti-Nazi films, what of it? Zanuck, a Methodist from Yahoo City, Nebraska, invoked every Hollywood film from The Birth of a Nation (1915) to The Grapes of Wrath (1940) to prove Hollywood a noble defender of the American way of life. As the gallery erupted in applause, he declared that Hollywood pictures sold Americanism “so strongly that when dictators took over Italy and Germany, what did Hitler and his flunky Mussolini do? The first thing they did was to ban our pictures and throw us out. They wanted no part of the American way of life.”20

Senators Clark, Wheeler, and Nye had no better luck intimidating the foreign-born mogul in their sights. A few days before Zanuck’s testimony, on September 25, 1941, Harry M. Warner was summoned for a daylong grilling. With Willkie at his side, Warner read a lengthy statement before deftly parrying the questions-cum-accusations from the committeemen. Warner was unapologetic and unbowed. He asserted his deep hatred for Nazism and pledged to do everything in his power to destroy Hitler. He praised the besieged British (“England is fighting for every right-thinking person in the world”) and lobbied for FDR’s National Defense program. His films were not propaganda, he explained, but all-too-true depictions of a world at war. “In truth, the only sin of which Warner Bros. is guilty is that of accurately recording on the screen the world as it is or as it has been,” he said. “I cannot conceive of how any patriotic citizen could object to a picture accurately recording the danger already existing within our country. Certainly it is not in the public interest for the average citizen to shut his eyes ostrich-like to attempts of Hitler to undermine the unity of those he seeks to conquer.” Warner also gently reminded Senator Nye that two years earlier he himself had personally endorsed Confessions of a Nazi Spy. Warner too was interrupted repeatedly by applause from the gallery.21 Outmaneuvered and outperformed by their witnesses, the committee adjourned.

As America moved toward December 7, 1941, two of the players most central to the motion picture dramas of 1933–1939 had left the scene. One was forcibly removed, the other passed away naturally.

On June 16, 1941, FDR severed diplomatic relations with Nazi Germany and ordered its embassy and consular offices shuttered. In Los Angeles, a wistful Dr. Georg Gyssling closed up shop. “Of course I regret leaving the United States,” said Gyssling, who had been consul in L.A. since Hitler had come to power and whose 13-year-old daughter, Angelika, had been born in America. “I have thousands of friends here. I hope someday to return.”

Gyssling set about packing up the furniture and burning official correspondence and secret papers. “The huge fireplace in the German Consulate at 403 S. Mariposa Avenue was clogging with the ashes of burned confidential documents yesterday [June 28, 1941],” reported the Los Angeles Times.22 Back in the fatherland, Gyssling continued to serve the Nazis as a political and cultural affairs officer, devoting himself to broadcasting and specializing in North American affairs. He survived the war, avoided prosecution at the Nuremberg trials, and died in Spain in 1965.23

The German-born transplant who really did have thousands of friends in the United States was also gone. Carl Laemmle had officially retired in 1936, after selling Universal Pictures, but Hollywood’s beloved Uncle Carl continued to preside over the industry as a kind of mogul emeritus. In 1937, at a huge outdoor barbeque at his mansion overlooking Beverly Hills and Benedict Canyon, he welcomed scores of well-wishers—all decked out in white aprons and chefs’ toques—to celebrate his seventieth birthday. Though nominally retired, after thirty years in the business he could not help but scan the trade papers for a hot new project. “I am keeping my eyes open and when a good story comes along, one like All Quiet on the Western Front, I will make it into a picture,” he promised. In a pensive mood, he confided a desire he had long harbored, assuming his health held up. “I have never been to Jerusalem,” he mused, “and it is one place I would like to visit. And if I feel up to it, I will make a trip there next month.”24

In the summer of 1938, Laemmle took his car, chauffeur, and secretary for a two-month vacation through Europe. He visited England, France, Switzerland, and Norway. Germany, the land of his birth, and Austria, now part of the Reich, were not on the itinerary.25 Nor was Jerusalem.

Always antsy, Laemmle devoted himself to enough charity work to keep two secretaries busy. As in the 1920s, when the people of his hometown of Laupheim faced starvation, he took a special interest in the well-being of his German countrymen, now suffering under another lethal threat. He signed affidavits, put up cash bond, and shepherded scores of refugees through the hurdles of American immigration policy, not just relatives but any desperate kinsman. In early 1939, Variety observed him working feverishly “to bring every refugee out of Laupheim now living there.”26

On August 24, 1939, as the headlines in the morning newspapers heralded the Hitler-Stalin Pact, Carl Laemmle died at his home in Beverly Hills. He was seventy-two years old. “The Laemmle servants, some of whom had been with him for thirty years, were inconsolable,” read a forlorn account in the Hollywood Reporter, and the hired help was not alone. The death of the benevolent old man cast a pall over the town.27 For many in Hollywood, who foresaw where the war clouds in Europe would ultimately settle, the passing of one of the industry’s founding fathers marked a shift in generations and perspective. Soon enough, Hollywood too would be at war, marshaled as a weapon in the arsenal of democracy.

Laemmle’s passing was also a reminder of what Germans and Germany had meant in Hollywood a lifetime ago, before 1933. At 12:30 p.m., during Laemmle’s funeral service at the Wilshire Temple B’Nai B’Brith, every studio in Hollywood stood silent for five minutes. Over 2,000 mourners attended the service. That evening, Warner Bros. paid homage to their competitor with a memorial program on KFWB. More than lip service, the eulogies and tributes that poured in had the ring of heartfelt affection.28 “It is reported he left an estate of four millions,” wrote Terry Ramsaye in Motion Picture Herald. “He gave away more than that before.”29

Earlier that week, Universal had reissued Laemmle’s proudest legacy, All Quiet on the Western Front. The film was billed as “The Uncensored Version,” a deceptive label that required an asterisk: “uncensored by war or military authorities.” Naturally, the 1939 rerelease had been vetted by the Breen office for conformity with the Production Code, not operative during the film’s original release in 1930, but American military authorities had never attempted to censor the film, and the version censored by the Germans had not been shown in America. John Deering, the voice of Confessions of a Nazi Spy, narrated both a special prologue and an epilogue comprised of newsreel clips reviewing the history of the Great War and what had transpired since 1930: the rise of the Nazis and the cupidity of the European powers, a grim survey highlighted by the now iconic newsreel footage of the book burning in Berlin in 1933 overseen by Joseph Goebbels. Among the volumes being tossed into the pyre was, of course, Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front.