27

CHASING THE ‘BIG LIFE’

I’ve always said that to achieve any big goal, you need a strong emotional connection to it; you need a very good reason for it. Because when you’re hating the grind and wondering why you’re doing what you’re doing, you need a foundation to fall back on.

Before the fire, I was an independent, vivacious go-getter. After it, I was apparently going to need a carer for the rest of my life – but, if I was lucky, there was always the possibility that one day I might drive again. I might even get married! And while I would never belittle those goals (I wanted and I want those things too), put together they didn’t add up to what I would call a ‘big life’ – the kind of life I’ve always wanted to live for myself.

That was the reason I trained for and completed two Ironmans. That was the reason I kept grinding away with my training, waking up each morning in the dark and hitting the road. The reason I kept pushing myself, even when I wanted more than anything else to give up.

When I was training, in the middle of a six-hour bike ride, in the middle of a miserable downpour, I kept coming back to this reason: I want to be fitter than I was in the Kimberley. I hate being told what I can and can’t do. I hate being limited. And the thing I hate the most is being underestimated.

What was the hardest thing about training for these huge events? The never-ending monotony of it. I struggled to fit in the training around my other commitments (much as I love my speaking engagements, or going to Peru to walk the Inca Trail, they take up a lot of time). There’s no triathlon club in Ulladulla, so I tried to organise group sessions for the dates I was in Sydney, and consoled myself the rest of the time with the thought that training solo would only make me mentally tougher.

I faced it like I had faced everything else in my journey. Namely: how do you eat an elephant? One bite at a time.

In the same way, during my recovery from the fire I would congratulate myself for getting through yet another day in hospital (literally: every night before I went to sleep I’d say to myself, ‘Well done, mate. You’ve made it through another day.’) I would just focus on the day I had ahead of myself.

If it was a day in which I had to do a two-hour brick session (a full bike workout followed immediately by a full run workout), I’d get up in the morning, do it, and then not think about it for the rest of the day.

A lot of the strategies I used to train for Ironman were in fact similar to the strategies I’d used in hospital and throughout my recovery. For example, when I’d struggled through a particularly hard day of physio or a hard day of training, I’d say to myself, ‘Once you’ve done this, it’ll be in the bank and you won’t have to do it again.’ Or let’s say my physio sessions would go for an hour and they’d be really painful, I’d break them up into five-minute sections and reward myself with some Gatorade at these points.

When it came to Kona, I knew I was going to need some pretty specific, well-thought-out strategies. I knew it was going to be a tougher physical challenge than any I had ever taken on before. So, when things got tough:

- I thought about everything I had to be grateful for – Michael, Mum, being alive, having the opportunity to compete in this iconic race.

- I was careful not to let the enormity of the task ahead of me overwhelm me; to stay in the moment. I knew that if I thought about everything I had to do that day, it’d be too much. So I broke it down. In the swim, I just focused on getting to the next buoy, on the bike ride I just thought about the next 10 kilometres, and on the run I focused on the next 2 kilometres, aid station to aid station.

- I compared any physical pain to what I’ve experienced in the past few years – and it paled in comparison.

- If a negative thought entered my mind, I immediately squashed it. For example, on the bike ride when it was super-windy I got really cranky, but before that crankiness could poison the rest of me, I would replace that negative thought with a positive one. Yes, it’s really windy – but every other competitor has gone through the same thing today.

- I used visualisation techniques. Often, I imagine that I’m a messenger for the Queen, and I have to get a message to her otherwise a war is going to break out and I’m going to have the deaths of thousands of people on my hands. Sounds crazy, I know, but it works.

At the time, Port Macquarie was the toughest physical challenge I had ever undertaken. But Kona was for me another level altogether. And in life we need to empty the tank. We don’t need to be the best, but we need to give our best.

For my training, I also had to be super-organised – I literally scheduled in each and every session for the months ahead. If I knew I was travelling a lot in a certain week, I’d let Bruce know and he’d tailor my sessions accordingly.

And I’d give myself a leave pass: no one is perfect. If I was travelling a lot for work, and couldn’t fit in proper meals or training sessions, I’d just accept that that day wasn’t going to be great. I set myself a ratio for my sessions, too: two per week had to be excellent, two could be sub-par and the rest I had to fully complete, even if I didn’t excel in them.

One of the scariest things going into Kona was the pressure I felt. Sure, some of it was the pressure I’d put on myself, but I’d also told half of Australia that I was doing an Ironman in Hawaii, and there were moments when I worried what I’d done. Had I set myself up for failure? Again, I tried to reframe it: by telling the country that I was doing an Ironman, I knew that come hell or high water I’d finish it. Even if it meant crawling across the line. It made me accountable.

In fact, in Kona shit got even more real because I had financial backing from sponsors. It’s tough when you know you have to go out there and perform and you’re wearing a logo.

I also worried about how my body would hold up. I’d get overuse injuries (which most athletes get training for an Ironman) and had to put in additional hours doing rehab or physio.

The thing about achieving a big goal is that it always gives back more than you put into it. I poured in hours and hours and hours and hours. I sweated, I cried, I wondered why I was doing it. I wondered what I was trying to prove. But in the end it was so empowering. It made me realise that the ‘process’ I’d used for recovering from hospital wasn’t just a fluke. I wasn’t just ‘born this way’. I’d used the same strategies to complete Port Macquarie, where they’d worked; then I used them to go on and complete Kona, and they worked there, too.

Finally, doing Kona made me realise that anything I want to achieve in life is possible – if I’m willing to put in the work to get myself there.

Training for Ironman

Because I know that at least a handful of you out there share my love of a spreadsheet – and because there will also be enough of you curious to know exactly what sort of training is required to compete in an Ironman, I’ve laid it out below.

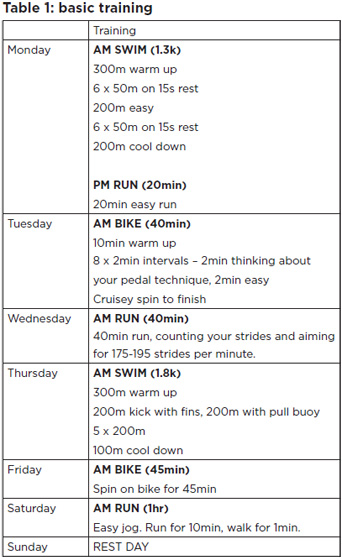

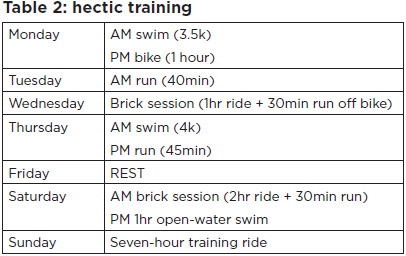

My training varied in intensity. Don’t forget, by the time Kona came around, I’d been preparing for Ironman for two years. At the very start, my training was basic (see Table 1: basic training). Later on, when I was working towards Kona, it got way more intense, until it was kind of taking over my life (see Table 2: hectic training).

Having a strict regime worked, though – and the best thing about it was when I would start to doubt my fitness levels, I’d look back through the previous months and (maybe even years) and see how far I had come.