After reading this chapter, you should be able to

1. define imagery,

2. discuss the effectiveness of imagery in enhancing sport performance,

3. discuss the where, when, why, and what of imagery use by athletes,

4. discuss the factors influencing imagery effectiveness,

5. describe how imagery works,

6. discuss the uses of imagery,

7. explain how to develop a program of imagery training, and

8. explain when to use imagery.

For many years athletes have been mentally practicing or rehearsing their motor skills. In fact, a large literature, termed “mental practice” (to distinguish it from physical practice), has been thoroughly reviewed on numerous occasions (e.g., Richardson, 1967a, 1967b; Weinberg, 1981, 2008) and has a long tradition in sport and exercise psychology. However, this general focus on mental practice has given way, in the last two decades, to systematically studying the potential uses and effectiveness of imagery in sport and exercise settings. The following quote by all-time golf great Jack Nicklaus demonstrates his use of imagery:

Before every shot I go to the movies inside my head. Here is what I see. First, I see the ball where I want it to finish, nice and white and sitting up high on the bright green grass. Then, I see the ball going there; its path and trajectory and even its behavior on landing. The next scene shows me making the kind of swing that will turn the previous image into reality. These home movies are a key to my concentration and to my positive approach to every shot.

—Jack Nicklaus (1976)

Nicklaus obviously believes that rehearsing shots in his mind before actually swinging is critical to his success. In fact, he has said that hitting a good golf shot is 10% swing, 40% stance and setup, and 50% the mental picture of how the swing should occur. In the 1980s and 1990s, multiple gold medalist Greg Louganis repeatedly told of his use of imagery before performing any of his dives. Picturing the perfect dive helped build his confidence and helped him prepare to make minute changes in his dive based on his body positioning during various phases. He pictured himself making a perfect dive and feeling different points of the dive. Nicklaus and Louganis are two of the many athletes who, for quite some time, have used imagery to enhance performance.

As scientific evidence accumulates supporting the effectiveness of imagery in sport and exercise settings, many more athletes and exercisers have begun using imagery, not only to help their performances, but also to make their experiences in sport and exercise settings more enjoyable. In this chapter we discuss the many uses of imagery in sport and exercise settings as well as the factors that make it more effective. Many people misunderstand the term, so let’s start by defining what exactly we mean by imagery.

defining Imagery

You probably have heard several different terms that refer to an athlete’s mental preparation for competition, including visualization, mental rehearsal, symbolic rehearsal, covert practice, imagery, and mental practice. These terms all refer to creating or recreating an experience in the mind. The process involves recalling from memory pieces of information stored from experience and shaping these pieces into meaningful images. These pieces are essentially a product of your memory, experienced internally through the recall and reconstruction of previous events. Imagery is actually a form of simulation. It is similar to a real sensory experience (e.g., seeing, feeling, or hearing), but the entire experience occurs in the mind.

All of us use imagery to recreate experiences. Have you ever watched the swing of a great golfer and tried to copy the swing? Have you ever mentally reviewed the steps and music of an aerobic dance workout before going to the class? We are able to accomplish these things because we can remember events and recreate pictures and feelings of them. We can also imagine (or “image”) and picture events that have not yet occurred. For example, an athlete rehabilitating from a shoulder separation could see herself lifting her arm over her head, even though she has not yet been able to do this. Many football quarterbacks view films of the defense they will be facing and then, through imagery, see themselves using certain offensive sets and strategies to offset the specific defensive alignments. Tennis great Chris Evert would carefully rehearse every detail of a match, including her opponent’s style, strategy, and shot selection. Here is how Evert described using imagery to prepare for a tennis match:

Before I play a match, I try to carefully rehearse what is likely to happen and how I will react in certain situations. I visualize myself playing typical points based on my opponent’s style of play. I see myself hitting crisp, deep shots from the baseline and coming to the net if I get a weak return. This helps me mentally prepare for a match, and I feel like I’ve already played the match before I even walk on the court. (Tarshis, 1977)

Imagery can, and should, involve as many senses as possible. Even when imagery is referred to as “visualization,” the kinesthetic, auditory, tactile, and olfactory senses are all potentially important. The kinesthetic sense is particularly important to athletes (Moran & MacIntyre, 1998) because it involves the feeling of our body as it moves in different positions and thus is particularly useful in enhancing performance. Using more than one sense helps to create more vivid images, thus making the experience more real as seen in this quote by Tiger Woods:

You have to see the shots and feel them through your hands.

Let’s look at how you might use a variety of senses as a baseball batter. First, you obviously use visual sense to watch the ball as the pitcher releases it and it comes toward the plate. You use kinesthetic sense to know where your bat is and to transfer your weight at the proper time to maximize power. You use auditory sense to hear the sound of the bat hit the ball. You can also use your tactile sense to note how the bat feels in your hands. Finally, you might use your olfactory sense to smell the freshly mowed grass.

Besides using your senses, learning to attach various emotional states or moods to your imagined experiences is also important. Recreating emotions (e.g., anxiety, anger, joy, or pain) or thoughts (e.g., confidence and concentration) through imagery can help control these states. In one case study, a hockey player had difficulty dealing with officiating calls that went against him. He would get angry, lose his cool, and then not concentrate on his assignment. The player was instructed to visualize himself getting what he perceived to be a bad call and then to use the cue words “Stick to ice” to remain focused on the puck. Similarly, an aerobic exerciser might think negatively and lose her confidence if she had trouble with remembering a specific routine. But via imagery, she could mentally rehearse the routine and provide positive instructional comments to herself if she did in fact make a mistake.

Evidence of Imagery’s Effectiveness

To determine whether imagery indeed does enhance performance, sport psychologists have looked at three different kinds of evidence: anecdotal reports, case studies, and scientific experiments. Anecdotal reports, or people’s reports of isolated occurrences, are numerous (Jack Nicklaus’ and Chris Evert’s remarks are examples). Many of our best athletes and national coaches include imagery in their daily training regimen, and ever more athletes report using imagery to help recover from injury. A study conducted at the United States Olympic Training Center (Murphy, Jowdy, & Durtschi, 1990) indicated that 100% of sport psychology consultants and 90% of Olympic athletes used some form of imagery, with 97% of these athletes believing that it helped their performance. In addition, 94% of the coaches of Olympic athletes used imagery during their training sessions, with 20% using it at every practice session. Finally, Orlick and Partington (1988) reported that 99% of Canadian Olympians also used imagery.

Despite the fact that anecdotal reports might be the most interesting evidence supporting the effectiveness of imagery, they are also the least scientific. A more scientific approach is the use of case studies, in which the researcher closely observes, monitors, and records an individual’s behavior over a period of time. Some earlier and later case studies demonstrated the effectiveness of imagery such as one using a field-goal kicker (Jordet, 2005; Titley, 1976). More recently researchers have used multiple-baseline case studies (i.e., studies of just a few people over a long period of time, with multiple assessments documenting changes in behavior and performance) and have found positive effects of imagery on performance enhancement and other psychological variables such as confidence and coping with anxiety (e.g., Evans, Jones, & Mullen, 2004). Many other studies have focused on psychological intervention packages, approaches that use a variety of psychological interventions (e.g., self-talk, relaxation, concentration training), along with imagery. For example, Suinn (1993) used a technique known as visuomotor behavior rehearsal (VMBR) that combines relaxation with imagery. Research with skiers using VMBR showed increases in the neuromuscular activity of the muscles used for skiing, and there were similar performance increases for karate performers who used VMBR (Seabourne et al., 1985). Other studies using imagery as part of a psychological intervention package have shown positive performance results with golfers, basketball players, triathletes, figure skaters, swimmers, and tennis players, although the improvements could not be attributed to imagery alone (see Perry & Morris, 1995; Weinberg & Williams, 2001, for reviews). Finally, qualitative investigations (e.g., Hanton & Jones, 1999b; Munroe, Giacobbi, Hall, & Weinberg, 2000; Thelwell & Greenlees, 2001) have also revealed the positive relationship between imagery and performance.

Evidence from scientific experiments in support of imagery also is impressive and clearly demonstrates the value of imagery in learning and performing motor skills (Feltz & Landers, 1983; Martin, Moritz, & Hall, 1999; Morris, Spittle, & Perry, 2004; Murphy, Nordin, & Cumming, 2008). These studies have been conducted across different levels of ability and in many different sports such as basketball, football, kayaking, track and field, swimming, karate, downhill and cross-country skiing, volleyball, tennis, and golf.

Imagery in Sport: Where, When, Why, and What

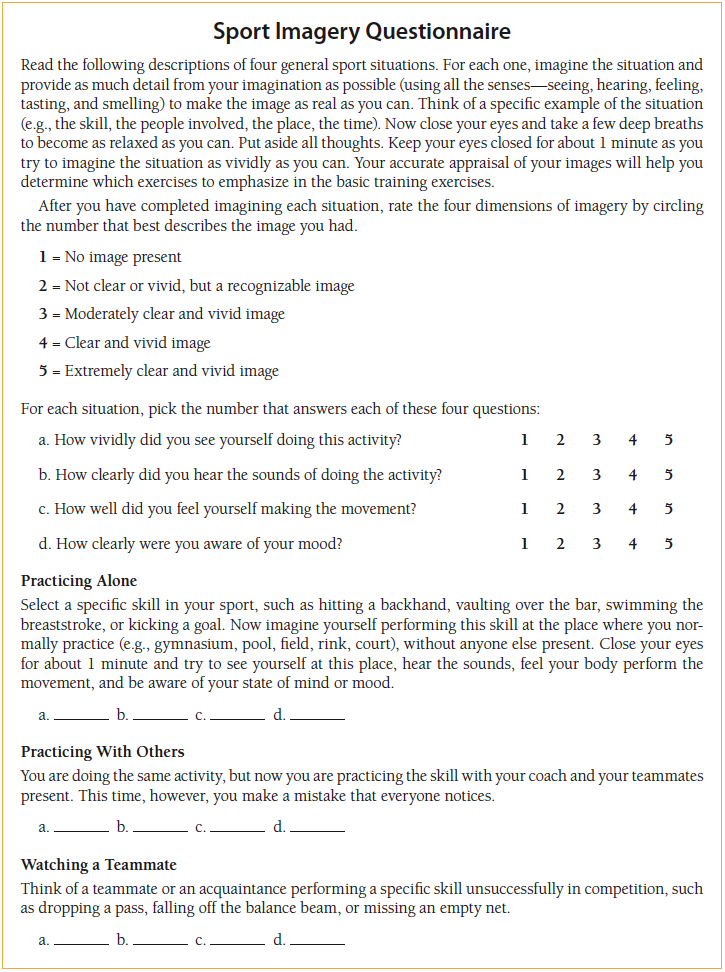

We now know from research that imagery can positively enhance performance. But recent findings, especially with the Sport Imagery Questionnaire (Hall, Mack, Pavio, & Hausenblas, 1998), have also revealed some of the details of imagery use, which should help practitioners design imagery training programs (discussed later in the chapter).

Where Do Athletes Image?

The majority of imagery use occurs in practice and competition, with athletes consistently using imagery more frequently in competition than in training (Munroe et al., 2000; Salmon, Hall, & Haslam, 1994). Interestingly, although the majority of imagery research has focused on practice situations (e.g., using imagery to facilitate learning), athletes appear to be using imagery more for performance enhancement (i.e., competing effectively), especially during precompetition. Therefore, coaches might want to focus more on teaching athletes proper imagery use during practice so that the athletes can transfer it over to competition and also practice the correct use of imagery on their own.

When Do Athletes Image?

Research has revealed (see Hall, 2001, for a review) that athletes use imagery before, during, and after practice; outside of practice (home, school, work); and before, during, or after competition. Some studies have indicated that athletes use imagery even more frequently outside of practice than during practices. Interestingly, athletes report using more imagery before competition than during or after competition, whereas imagery use is more frequent during practices than before or after practices. Imagery after practices and competitions appear to be underused. This is unfortunate, because vivid images of performance should be fresh in athletes’ minds after practice—which should facilitate the efficacy of imagery right after practicing or performing.

It has also been suggested that athletes use imagery while they are injured. However, research has revealed that imagery is still used more frequently during competition and practice than during injury rehabilitation. When imagery is used for rehabilitation purposes, the focus tends to be on motivation to recover and to rehearse rehabilitation exercises. More emphasis should be placed on imagery during recovery from injury, because a variety of benefits (including faster healing) have been identified.

Why Do Athletes Image?

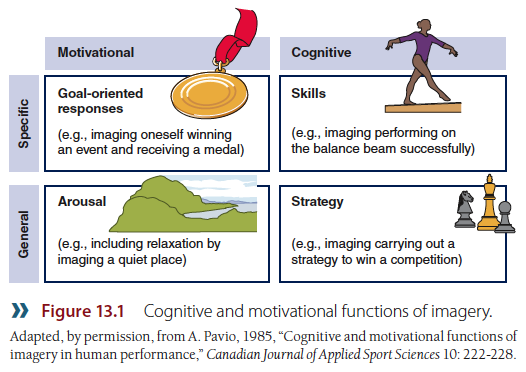

When attempting to determine why performers and exercisers use imagery, we should differentiate content from function. Content relates to what a person images (e.g., muscles feeling loose after a hard workout), whereas function refers to why the person images (to feel relaxed). Thus, in discussing why individuals image, we focus on function. To help in this regard, Pavio (1985) distinguished between two functions of imagery: motivational and cognitive. He suggested that imagery plays both cognitive and motivational roles in mediating behavior, each capable of being oriented toward either general or specific behavioral goals (see figure 13.1).

On the motivational specific (MS) side, people can use imagery to visualize specific goals and goal-

oriented behaviors, such as winning a particular contest or being congratulated for a good performance. In fact, imagery can help an individual set specific goals and then adhere to the training to reach these goals (Martin, Moritz, & Hall, 1999). Empirical testing has determined that motivational general imagery should be classified into motivational general—mastery (MG-M) and motivational general—arousal (MG-A). Imaging performing well to maintain confidence is an example of MG-M, although achieving mental toughness, positivism, and focus has also been identified as a potential outcome of MG-M imagery. Similarly, using imagery to “psych-up and increase arousal” (Caudill, Weinberg, & Jackson, 1983; Munroe et al., 2000) is an example of MG-A, as is using imagery to help achieve relaxation and control (Page, Sime, & Nordell, 1999). Investigating the effectiveness of these different types of motivational imagery, Nordin and Cumming (2008) found that indeed MS was most effective in helping athletes maintain confidence and stay focused. However, all three types of motivational imagery were effective in enhancing motivation, and MG-A and MG-M were both effective in regulating arousal (e.g., psyching up and calming down).

On the cognitive specific (CS) side, imagery focuses on the performance of specific motor skills, whereas cognitive general (CG) imagery refers to rehearsing entire game plans, strategies of play, and routines inherent in competitions. Along these lines, research (Nordin & Cumming, 2008) has revealed that CS imagery was rated most effective for skill learning and development as well as skill execution and performance enhancement. Cognitive general imagery was rated most effective for strategy learning and development and for strategy execution. It should be noted that such mental training should supplement and complement physical practice, not replace it.

An interesting study (Short & Short, 2005) demonstrated that the function of imagery might be dependent on the individual athlete. Specifically, it was found that different athletes view the same image differently. Therefore, when developing an imagery script, make sure the athlete perceives the function as facilitative. For example, an athlete might perceive the image of an Olympic gold medalist as threatening rather than motivational because she feels pressure to win a medal.

What Do Athletes Image?

Various researchers (e.g., Munroe et al., 2000) have investigated exactly what and how individuals image. The findings relate to four aspects of imaging: images of the surroundings in which the athlete competes, the positive or negative character of images, the senses involved in imagery (types of imagery), and the perspective (internal vs. external) the athlete takes in creating imagery.

Surroundings

It is not surprising that athletes have reported imagining competition surroundings (e.g., venue, spectators). They have most often done this when using imagery to prepare for an event because imagining competition surroundings can increase the vividness of the image and make it more realistic. A cross country runner illustrates this type of imagery well.

I think about the whole course in the evening

… before I go to sleep I lay there … and I’ll just imagine from start to finish every part of the course and where the hills are.

Nature of Imagery

Most studies classify imagery as positive or negative. Positive images are most often reported during practices and precompetition. For example, one athlete reported imaging this way:

During practices I am thinking about nice places and nice things. It gets your mind off it. Then it’s been a half-hour into practice.

Negative images were most often reported during competitions, as in this example:

I sometimes imagine hitting a bad shot in golf. And guess what, I usually do hit a bad shot.

Although the focus of imagery research has been on generating positive images, sometimes imagery can have an adverse affect on performance (especially negative images). In fact, when directly asked, 35% of athletes, 25% of coaches, and 87% of sport psychologists could point to examples where imagery inhibited performance. The following situations should be monitored carefully because they might contribute to adverse outcomes of imagery use (Murphy & Martin, 2002):

Oftentimes we tell ourselves “not to do something.” But does this have a positive or negative effect? Beilock, Afremow, Rabe, and Carr (2001) investigated the notion of suppressive imagery (trying to avoid a particular error, as in, Don’t picture a double fault). Results revealed that the accuracy of a group that used positive imagery improved regardless of imagery frequency. However, for the imagery suppression group (in which participants were told not to image undershooting the cup and then not to image overshooting the cup), accuracy improved when they imaged before every third putt but decreased when they imaged before each putt. Even replacing this negative image with a positive image did not help performance. These results are consistent with research by Ramsey, Cumming, and Edwards (2008), who found that suppressive imagery (not thinking about hitting the ball into the sand bunker next to the green) produced significantly poorer putting performance than facilitative imagery (seeing yourself making the putt). They argue that simply mentioning the sand bunker increased players’ awareness of the bunker, which in turn negatively affected their concentration. This reinforces the notion that telling yourself not to image something that you don’t want to do will in fact make it more likely that you will image it, thus hindering actual

performance.

A recent investigation looked at how positive or negative imagery combined with self-talk influenced performance. Specifically, researchers (Cumming, Nordin, Horton, & Reynolds, 2006) found that participants in the facilitative imagery/facilitative self-talk condition improved their performance, whereas participants in the debilitative imagery/debilitative self-talk condition decreased their performance. Future research needs to determine the exact combinations that produce the best performance.

Type of Imagery

Researchers have found that athletes describe basically four types of imagery (visual, kinesthetic, auditory, and olfactory) and that they use visual and kinesthetic imagery most often, and to the same extent. However, this does not mean that the auditory and olfactory aspects of imagery are not important. For example, a professional tennis player remarked on the importance of auditory imagery:

If you’re really visualizing something, then you should be aware of the sounds because different balls have different sounds. Balls sound different when they are sliced than when they are hit with topspin. The sound can be really important because if you imagine what it sounds like to hit a sliced backhand, it will have a different sound than a topspin. It gets to you especially in your mind set.

In an interesting study comparing the effectiveness of learning a new task using visual information (watching a videotape) versus learning via kinesthetic awareness (feeling where one’s arm was in space as one performed the movement, blindfolded), results revealed that the visual imagery group performed significantly better than the kinesthetic imagery group, although both imagery groups performed better than the control group (Farahat, Ille, & Thon, 2004). However, the best way to proceed (if possible) is to combine both the visual and kinesthetic information in imaging skills to maximally enhance performance.

Imagery Perspective

Athletes usually take either an internal or external perspective for viewing their imagery (Mahoney & Avener, 1977). Which perspective is used depends on the athlete and the situation. We’ll look briefly at each perspective.

Internal imagery refers to imagery of the execution of a skill from your own vantage point. As if you had a camera on your head, you see only what you would see if you actually executed the particular skill. As a softball pitcher, for instance, you would see the batter at the plate, the umpire, the ball in your glove, and the catcher’s target, but not the shortstop, second baseman, or anything else out of your normal range of vision. Because internal imagery comes from a first-person perspective, the images emphasize the feel of the movement. As a softball pitcher, you would feel your fingers gripping the ball, the stretch of your arm during the backswing, the shift of weight, and finally the extension of your arm upon release.

In using external imagery, you view yourself from the perspective of an outside observer. It is as if you are watching yourself in a movie. For example, if a baseball pitcher imagined pitching from an external perspective, he would see not only the batter, catcher, and umpire but also all the other fielders. There is little emphasis on the kinesthetic feel of the movement because the pitcher is simply watching himself perform it.

Initial studies suggested that elite athletes favored an internal perspective, but other research has failed to support this contention (see Hall, 2001, for a review). Regarding performance results, few reliable differences have been established between external and internal imagery. In addition, it was virtually impossible to characterize participants as strictly internal or external imagers because people’s images varied considerably, both within and between images (Epstein, 1980; Mumford & Hall, 1985). In fact, most Olympic athletes surveyed by Murphy, Fleck, Dudley, and Callister (1990) indicated that they use both internal and external imagery.

Hardy and his colleagues (Hardy, 1997; Hardy & Callow, 1999; White & Hardy, 1995) argued that task differences may influence the use of each perspective. They proposed that external imagery has superior effects on the acquisition and performance of skills that depend heavily on form for their successful execution, whereas the internal perspective is predicted to be superior for the acquisition and performance of tasks that depend heavily on perception and anticipation for successful execution. Hardy and colleagues provide some preliminary data to support their contentions on form-based tasks such as gymnastics, karate, and rock climbing (Hardy & Callow, 1999), although some other more recent data suggested that imagery perspective did not make a difference in relation to the type of task performed (Cumming & Ste-Marie, 2001). On a final note, tasks varying along the continuum of open (time pressured, changing environment, e.g., basketball) and closed (not time stressed, environment stable, e.g., golf) sports may be affected by internal and external imagery. For example, preliminary research by Spittle and Morris (2000) indicated that internal imagery might be more beneficial for closed tasks and external imagery more beneficial for open tasks. Obviously, more research is necessary to untangle this thorny issue.

Even though the research is somewhat inconclusive, a review of this literature showed that internal imagery produced more electrical activity in the muscles involved in the imagined activity than did external imagery (Hale, 1994). Internal imagery appears to make it easier to bring in the kinesthetic sense, feel the movement, and approximate actual performance skills.

In summary, many people switch back and forth between internal and external imagery. As one Olympic rhythmic gymnast reported, “Sometimes you look at it from a camera view, but most of the time I look at it as what I see from within, because that’s the way it’s going to be in competition” (Orlick & Partington, 1988, p. 114). The important thing appears to be getting a good, clear, controllable image, regardless of whether it is from an internal or an external perspective.

Factors Affecting the Effectiveness of Imagery

Several factors seem to determine the extent to which imagery can improve performance. Keep these in mind to maximize the effectiveness of imagery.

How Imagery Works

How can just thinking about jumping over the high bar, hitting a perfect tennis serve, healing an injured arm, or sinking a golf putt actually help athletes accomplish these things? We can generate information from memory that is essentially the same as an actual experience; consequently, imaging events can have an effect on our nervous system similar to that of the real, or actual, experience. “Imagined stimuli and perceptual or ‘real’ stimuli have a qualitatively similar status in our conscious mental life” (Marks, 1977, p. 285). Sport psychologists have proposed five explanations of this phenomenon.

Psychoneuromuscular Theory

The psychoneuromuscular theory originated with Carpenter (1894), who proposed the ideomotor principle of imagery. According to this principle, imagery facilitates the learning of motor skills because of the nature of the neuromuscular activity patterns activated during imaging. That is, vividly imagined events innervate the muscles in somewhat the same way that physically practicing the movement does. These slight neuromuscular impulses are hypothesized to be identical to those produced during actual performance but reduced in magnitude (indeed, the impulses may be so minor that they do not actually produce movement).

The first scientific support of this phenomenon came from the work of Edmund Jacobson (1931), who reported that the imagined movement of bending the arm created small muscular contractions in the flexor muscles of the arm. In research with downhill skiers, Suinn (1972, 1976) monitored the electrical activity in the skiers’ leg muscles as they imagined skiing the course; results showed that the muscular activity changed during the skiers’ imaginings. Muscle activity was highest when the skiers were imagining themselves skiing rough sections in the course, which would actually require greater muscle activity.

When you vividly imagine performing a movement, you use neural pathways similar to those you use in actual performance of the movement. Let’s take the example of trying to perfect your golf swing. The goal is to make your swing as fluid and natural as possible. To accomplish this, you imagine taking a bucket of balls to the driving range and practicing your swing, trying to automate it (i.e., groove your swing). In effect, you are strengthening the neural pathways that control the muscles related to your golf swing. Although there is some research to support this explanation of how imagery works, other research indicates that the electrical activity produced by the muscles does not mirror the actual pattern of activity when actually performing the movement (Slade, Landers, & Martin, 2002). More definitive research is necessary to empirically substantiate that imagery actually works as predicted by the psychoneuromuscular theory.

Murphy (2005) noted that with new imaging techniques such as positron emission tomography scanning and functional magnetic resonance imaging, we can look at pictures of the brain of a person who is resting quietly and compare them with pictures taken when that person is imaging, for example, a 400-meter race. These pictures show that certain areas of the cerebral cortex are much more active when a person uses imagery than when he or she is resting. More specifically (Decety, 1996), it has been found that when someone imagines starting a movement, various areas of the brain become active, including the premotor cortex as the action is prepared, the prefrontal cortex as the action is initiated, and the cerebellum during the control of movement sequences that require a specific order. Even more fascinating is the discovery that many of the same areas of the brain that are used during the process of visual perception are also used during visual imagery, which means that imagery shares some of the same brain processes and pathways with actual vision. These are exciting new developments that will require more research to document how imagery actually changes our physiology, which in turn enhances performance.

Symbolic Learning Theory

Sackett (1934) argued that imagery can help individuals understand their movements. His symbolic learning theory suggests that imagery may function as a coding system to help people understand and acquire movement patterns. That is, one way individuals learn skills is by becoming familiar with what needs to be done to successfully perform them. When an individual creates a motor program in the central nervous system, a mental blueprint is formed for successfully completing the movement. For example, in a doubles match in tennis if a player knows how her partner will move on a certain shot, she will be able to better plan her own course. This will help the athlete plan her movement patterns.

Thorough reviews of the literature (Driskell, Cooper, & Moran, 1994; Feltz & Landers, 1983) have shown that participants using imagery performed consistently better on tasks that were primarily cognitive (e.g., football quarterbacking) than on those that were more mostly motoric (e.g., weightlifting). Of course, most sport skills have both motor and cognitive components; imagery can be effective to an extent, therefore, in helping players with a variety of skills.

Bioinformational Theory

Probably the best-developed theoretical explanation for the effects of imagery is Lang’s bioinformational theory (1977, 1979). Based on the assumption that an image is a functionally organized set of propositions stored by the brain, the model holds that a description of an image consists of two main types of statements: response propositions and stimulus propositions. Stimulus propositions are statements that describe specific stimulus features of the scenario to be imagined. For example, a weightlifter at a major competition might imagine the crowd, the bar he is going to lift, and the people sitting or standing on the sidelines. Response propositions, on the other hand, are statements that describe the imager’s response to the particular scenario, and they are designed to produce physiological activity. For example, having a weightlifter feel the weight in his hands as he gets ready for his lift as well as feel a pounding heart and a little tension in his muscles is a response proposition.

The crucial point is that response propositions are a fundamental part of the image structure in Lang’s theory. In essence, the image is not only a stimulus in the person’s head to which the person responds. In fact, imagery instructions (especially motivation general—arousal) that contain response propositions elicit greater physiological responses (i.e., increases in heart rate) than do imagery instructions that contain only stimulus propositions (Cumming, Olphin, & Law, 2007). Imagery scripts should contain both stimulus and response propositions, which are more likely to create a vivid image than stimulus propositions alone.

Response Versus Stimulus Propositions: Lang’s Bioinformational Theory

To be most effective, imagery scripts should contain both stimulus and response propositions, although with emphasis on response propositions. Here are examples of each:

Script Weighted With Stimulus Propositions

It is a beautiful autumn day and you are engaged in a training program, running down a street close to your home. You are wearing a bright red track suit, and as you run you watch the wind blow the leaves from the street onto a neighbor’s lawn. A girl on a bicycle passes you as she delivers newspapers. You swerve to avoid a pothole in the road, and you smile at another runner passing you in the opposite direction.

Script Weighted With Response Propositions

It is a crisp autumn day and you are engaged in a training run, going down a street close to your home. You feel the cold bite of air in your nose and throat as you breathe in large gulps of air. You are running easily and smoothly, but you feel pleasantly tired and can feel your heart pounding in your chest. Your leg muscles are tired, especially the calf and thigh muscles, and you can feel your feet slapping against the pavement. As you run you can feel a warm sweat on your body.

Triple Code Model

The final model goes a step further in stating that the meaning the image has to the individual must also be incorporated into imagery models. Specifically, Ahsen’s (1984) triple code model of imagery highlights understanding three effects that are essential aspects or parts of imagery; the effects are referred to as ISM. The first part is the image (I) itself. “The image represents the outside world and its objects with a degree of sensory realism which enables us to interact with the image as if we were interacting with the real world” (Ahsen, 1984, p. 34). The second part is the somatic response (S): The act of imagination results in psychophysiological changes in the body (this contention is similar to Lang’s bioinformational theory). The third aspect of imagery (mostly ignored by other models) is the meaning (M) of the image. According to Ahsen, every image imparts a definite significance, or meaning, to the individual imager; the same set of imagery instructions will never produce the same imagery experience for any two people.

Individual differences can be seen in Murphy’s (1990) description of figure skaters who were asked to relax and concentrate on “seeing a bright ball of energy, which I inhale and take down to the center of my body.” One skater imagined a glowing energy ball “exploding in my stomach [and] leaving a gaping hole in my body.” Another skater said that the image of the ball of energy “blinded me so that when I began skating I could not see where I was going and crashed into the wall of the rink.” In essence, Ahsen’s triple code model recognizes the powerful reality of images for the individual and also encourages us to seek the meanings of the images to them.

Psychological Explanations

Although not full-blown theories, a number of psychological explanations have been put forth to explain the effects of imagery. For example, one notion is based on attention–arousal set theory and argues that imagery functions as a preparatory set that assists in achieving an optimal arousal level. This optimal level of arousal allows the performer to focus on task-relevant cues and screen out task-irrelevant cues.

A second area explaining imagery effectiveness from a psychological perspective argues that imagery helps build psychological skills that are critical to performance enhancement, such as increased confidence and concentration and decreased anxiety. For example, a golfer might have missed a crucial putt in the past to lose a tournament because he tightened up and got distracted by the crowd. Now, he sees himself taking a deep breath, going through his preshot routine, and feeling confident about making the putt. In his imagery he sees himself sinking the putt and winning the tournament.

Imagery can also serve a motivational function by helping the performer to focus on positive outcomes, whether that be improving on previous performance or doing well against the competition. Therefore, an exerciser could image a great workout with her body getting leaner and stronger, or an athlete could image winning a competition and having a gold medal placed around his neck.

In summary, the five theories or explanations—psychoneuromuscular theory, symbolic learning theory, bioinformational theory, the triple code model, and psychological explanations—all assert that imagery can help program an athlete both physically and mentally. All these explanations have found some support from research, although they have also been closely scrutinized. You might regard imagery as a strong mental blueprint of how to perform a skill, which should result in quick and accurate decision making, increased confidence, and improved concentration. In addition, the increased neuromuscular activity in the muscles helps players make movements more fluid, smooth, and automatic. As Moran (2004) suggested, taken together, these approaches suggest that imagery might be best understood as a centrally mediated cognitive activity that mimics perceptual, motor, and emotional experiences in the brain. Thus, the cognitive, physiological, and psychological components of an activity can be captured through different modalities with the use of imagery.

Uses of Imagery

Athletes can use imagery in many ways to improve both physical and psychological skills. Uses include improving concentration, enhancing motivation, building confidence, controlling emotional responses, acquiring and practicing sport skills and strategies, preparing for competition, coping with pain or injury, and solving problems.

Using imagery can enhance your confidence, because if you imagine yourself having a good race and finishing a competition, and being excited about the time, you see that this gives you confidence before the next race…. Imagery can definitely give you confidence the next time you step up to the blocks.

Keys to Effective Imagery

Like all psychological techniques, imagery skill is acquired through practice. Some participants are good at it, whereas others may not even be able to get an image in their minds. There are two keys to good images—vividness and controllability. We’ll consider each of these in turn.

Vividness

Good imagers use all of their senses to make their images as vivid and detailed as possible. It is important to create as closely as possible the actual experience in your mind. Pay particular attention to environmental detail, such as the layout of the facilities, type of surface, and closeness of spectators. Experience the emotions and thoughts of the actual competition. Try to feel the anxiety, concentration, frustration, exhilaration, or anger associated with your performance. All of this detail will make the imagined performance more real. If you have trouble getting clear, vivid images, first try to imagine things that are familiar to you, such as the furniture in your room. Then use the arena or playing field where you normally play and practice. You will be familiar with the playing surface, grandstands, background, colors, and other environmental details. You can practice getting vivid images with the three vividness exercises that follow. (We also recommend trying the exercises in Put Your Mother on the Ceiling by Richard DeMille, 1973.)

Using Imagery in Exercise

This chapter has focused predominantly on imagery in sport. However, imagery in exercise has recently begun to receive more attention (Hausenblas et al., 1999; Gammage, Hall, & Rodgers, 2000). The following quote illustrates the use of imagery in exercise.

For weeks before actually exercising, I visualized myself moving freely as I worked out. I enjoyed this image and it helped me to start working out.

In extending this recent research, Giacobbi, Hausenblas, Fallon, and Hall (2003) found a number of different functions of imagery including the following:

These functions suggest that exercise imagery helps sustain the motivation and self-efficacy beliefs of exercise participants, which may then lead to greater involvement in physical activity. Exercise participants should be encouraged to use imagery to see themselves achieving their goals especially through appearance and technique imagery, because these have been shown to be related to intrinsic motivation (Wilson, Rodgers, Hall, & Gammage, 2003). In addition, individual differences need to be considered; for example, active individuals use more appearance or health imagery than less active individuals, and younger males (18-25) use more exercise technique imagery than older males (45-65) (Giacobbi, 2007).

Controllability

Another key to successful imagery is learning to manipulate your images so they do what you want them to. Many athletes have difficulty controlling their images and often find themselves repeating their mistakes as they visualize. A baseball batter might visualize his strikeouts; a tennis player, her double faults; or a gymnast, falling off the uneven parallel bars. Controlling your image helps you to picture what you want to accomplish instead of seeing yourself make errors. The key to control is practice. The following description by an Olympic springboard diver shows how practice can help overcome an inability to control one’s images:

It took me a long time to control my images and perfect my imagery, maybe a year, doing it every day. At first I couldn’t see myself; I always saw everyone else, or I would see my dives wrong all the time. I would get an image of hurting myself, or tripping on the board, or I would see something done really bad. As I continued to work on it, I got to the point where I could see myself doing a perfect dive and the crowd at the Olympics. But it took me a long time. (Orlick & Partington, 1988, p. 114)

We suggest the following controllability exercises for practice.

How to Develop an Imagery Training Program

Now that you know the principles underlying the effectiveness of imagery and are familiar with techniques for improving vividness and controllability, you have the basics you need to set up an imagery training program. To be effective, imagery should become part of the daily routine. Imagery programs should be tailored to the needs, abilities, and interests of each athlete or exerciser. Simons (2000) provided some good practical tips for implementing an imagery training program in the field. In addition, Holmes and Collins (2001) offered some guidelines to make imagery more effective, which they call their PETTLEP program because it emphasizes the following:

In testing this model, Smith, Wright, Allsopp, and Westhead (2007) found support for including the elements of the PETTLEP model in one’s imagery. More specifically, they found that an athlete performing imagery while wearing the clothing she would usually wear when playing her sport, along with doing the imagery on the actual field (i.e., imaging while wearing her hockey uniform while standing on the team’s hockey pitch), produced significantly better performance than doing imagery wearing the clothing alone (i.e., imaging while wearing her hockey uniform), which in turn produced better performance than simply doing imagery in a more traditional manner (imaging at home without sport-specific clothing). In a second study, Wright and Smith (2007) found that the PETTLEP group performed as well as a performance-only group and better than a traditional imagery group on a cognitive task. These results provide initial support for using PETTLEP principles while performing imagery to enhance its effectiveness.

An even newer model (Guillot & Collet, 2008) was proposed to help guide imagery research and practice. The motor imagery integrative model posits four specific areas and then some subareas in which imagery can affect various aspects of sport performance:

Evaluate Imagery Skill Level

The first step in setting up imagery training is to evaluate the athlete’s or student’s current level of imagery skill. Because imagery is a skill, individuals differ in how well they can do it. Measuring someone’s ability in imaging is not easy, however, because imagery is a mental process and therefore not directly observable. As a result, sport psychologists use mostly questionnaires to try to discern the various aspects of imagery content. Tests of imagery date back to 1909 when the Betts Questionnaire on Mental Imagery was first devised. Later the Vividness of Movement Imagery Questionnaire (Issac, Marks, & Russell, 1986) was developed to measure visual imagery as well as kinesthetic imagery. In addition, Hall and colleagues (1998) developed the Sport Imagery Questionnaire (SIQ), which contains questions about the frequency with which individuals use various types of imagery (e.g., imaging sport skills, strategies of play, staying focused, or the arousal that may accompany performance). The frequency items in the SIQ indicate that athletes found these particular imagery techniques and strategies effective (Weinberg, Butt, Knight, Burke, & Jackson, 2003). Finally, in further extending the SIQ (Short, Monsma, & Short, 2004), researchers found that the function, not the content, of the image was the most critical. In essence, if an athlete uses imagery to enhance self-confidence, then it doesn’t matter exactly what the image is, as long as it enhances confidence.

These imagery questionnaires can be used to evaluate various aspects of imagery ability and use; the practitioner chooses the most appropriate instrument for a specific situation. As an example and to see how good your own imagery skills are, complete the “Sport Imagery Questionnaire” on pages 310-311 (Martens, 1982b), which measures how well athletes can use all their senses while imaging. Note that this questionnaire has been updated (called the Sport Imagery Ability Measure) to reflect different sense modalities (visual, auditory, kinesthetic, tactile, olfactory, and gustatory) as well as the dimensions of control, ease, vividness, speed and duration of the image, and the emotion associated with the imagery (Watt, Morris, & Andersen, 2004).

Implement Feedback Into Imagery Training

After compiling feedback from the questionnaire, players and coaches can determine which areas to incorporate into an athlete’s daily training regimen. The imagery program need not be complex or cumbersome, and it should fit well into the individual’s daily training routine. Following are tips and guidelines for implementing a successful program in imagery training (Vealey & Greenleaf, 1998).

Practice in Many Settings

Many people think that lying down on a couch or chair is the only way to do imagery. Although athletes might want to start to practice imaging in a quiet setting with few distractions, once they become proficient at imagery, they should practice it in many different settings; for example, in the locker room, on the field, during practice, at the pool. People who are highly skilled in the use of imagery can perform the technique almost anywhere. As skills develop, people learn to use imagery amid distractions and even in actual competition. Sometimes athletes’ imagery practice might include holding a bat, club, or ball in their hands or moving into or being in the position called for in performance of the skill (e.g., sitting on your knees for kayaking or standing up and getting into a batting stance for a baseball player).

Aim for Relaxed Concentration

Imagery preceded by relaxation is more effective than the use of imagery alone (Weinberg, Seabourne, & Jackson, 1981). Before each imagery session, athletes should relax by using deep breathing, progressive relaxation, or some other relaxation procedure that works for them. Relaxation is important for two reasons: It lets the person forget everyday worries and concerns and concentrate on the task at hand, and it results in more powerful imagery because there is less competition with other stimuli.

Establish Realistic Expectations and Sufficient Motivation

Some athletes are quick to reject such nontraditional training as imagery, believing that the only way to improve is through hard physical practice. They are skeptical that visualizing a skill can help improve its performance. Such negative thinking and doubt undermine the effectiveness of imagery. Other athletes believe that imagery can help them become the next Tiger Woods or Serena Williams, as if imagery is magic that can transform them into the player of their dreams. The truth is simply that imagery can improve athletic skills if you work at it systematically. Excellent athletes are usually intrinsically motivated to practice their skills for months and even years. Similar dedication and motivation are needed to develop psychological skills. Yet many athletes do not commit to practicing imagery systematically.

Use Vivid and Controllable Images

When you use imagery relating to performance of a skill, try to use all your senses and feel the movements as if they were actually occurring. Many Olympic teams visit the actual competition site months in advance so they can visualize themselves performing in that exact setting, with its colors, layout, construction, and grandstands. Moving and positioning your body as if you were actually performing the skill can make the imagery and feeling of movement more vivid. For example, instead of lying down in bed to image kicking a soccer goal, stand up and kick your leg as if you were actually doing so. Imagery can be used during quick breaks in the action, so it is important to learn to image with your eyes open as well as closed. Work on controlling images to do what you want them to do and thus produce the desired outcome.

Apply Imagery to Specific Situations

Make sure to use imagery in specific situations, tailored to your individual needs. For example, if a softball pitcher has trouble staying calm with runners on base, she should simulate different situations with different counts, game scores, numbers of outs, and numbers of base runners to groove strong and consistent mental and physical responses to the pressure of these situations. Repeatedly imaging just pitching well would not be as effective as imaging pitching in these different difficult situations.

Maintain Positive Focus

Focus in general on positive outcomes, such as kicking a field goal, getting a base hit, completing a successful physical therapy session, or scoring a goal. Sometimes using imagery to recognize and analyze errors is beneficial (Mahoney & Avener, 1977) because nobody is perfect and we all make mistakes every time we play. It is also important, however, to be able to leave the mistake behind and focus on the present. Try using imagery to prepare for the eventuality of making a mistake and effectively coping with the error.

For trouble with a particular mistake or error, we suggest the following: First try to imagine the mistake and determine the correct response. Then immediately imagine performing the skill correctly. Repeat the image of the correct response several times, and follow this immediately with actual physical practice. This process will help you absorb what it looks like and how it feels to perform the skill well.

Errors and mistakes are part of competition, so athletes should be prepared to deal with them effectively. The importance of preparing for errors and unlikely events was chronicled by Gould and colleagues through interviews with Olympic coaches and athletes (e.g., Gould, Greenleaf, Lauer, & Chung, 1999; Gould, Guinan, et al., 1999). This focus on errors and a coping strategy is highlighted in the following quote by a three-time Olympian:

It’s as if I carry around a set of tapes in my mind. I play them occasionally, rehearsing direct race strategies. Usually I imagine the race going the way I want—I set my pace and stick to it. But I have other tapes as well—situations where someone goes out real fast and I have to catch him, or imaging how I will cope if the weather gets really hot. I even have a “disaster” tape where everything goes wrong and I’m hurting badly, and I imagine myself gutting it out. (Murphy & Jowdy, 1992, p. 242)

Example of an Imagery Script (for Tennis)

You step out on the court to warm up, and your feet feel light and bouncy. Your ground strokes are fluid and easy, yet powerful. You feel the short backswing and nice follow-through on your shots. You are moving around the court freely and effortlessly, getting to all of your opponent’s shots. You feel a nice stretch on the back of your arm and in your low back as you warm up your overhead. The overheads are hit clean and right in the middle of your racket. You warm up your serve, and your motion feels fluid; you’re really stretching out and transferring your weight into the ball. The ball is hitting the spots in the service box you are aiming for with a variety of spins and speeds.

See yourself starting the match serving and getting right into the flow of the match. Visualize some strong serves where your opponent can only just get the ball back in the midcourt and you decisively put the ball away with short, topspin, angled strokes. Your next point is a long rally from the baseline. See yourself keeping the ball deep and hitting it firmly but yet with a good margin for error. Finally your opponent hits a short ball and you come in on a slice down the line to the backhand side. Your opponent tries a down-the-line passing shot but you anticipate this and are right there to hit a short cross-court volley winner. You finish the game with a big serve ace down the middle. The game gets you off to a good start and gets your adrenaline flowing and concentration focused on the match. As you get ready to walk on the court you are feeling relaxed and confident. You can’t wait to hit the ball.

Consider Use of DVDs, Videotapes, and Audiotapes

Many athletes can get good, clear images of their teammates or frequent opponents but have trouble imaging themselves. The reason is that it is difficult to visualize something you have never seen. Seeing yourself on videotape for the first time is quite eye-opening, and people typically ask, “Is that me?” A good procedure for filming athletes is to film them practicing, carefully edit the tape (usually in consultation with the coach or athlete) to identify the perfect or near-perfect skills, and then duplicate the sequence repeatedly on the tape. The athlete observes her skills in the same relaxed state prescribed for imagery training. After watching the film for several minutes, she closes her eyes and images the skill.

Another way to use video is to make “highlight videos” of individuals playing well in particular situations during a competition. People can use such videos with their own imagery to boost confidence and motivation or simply to enhance the clarity and vividness of their images. In addition, many athletes make their own cassette tapes rather than using commercial tapes. Personal tapes should include specific verbal cues that are familiar and meaningful to the performer, including specific responses to various situations that may arise during a game. Performers can also modify a tape to fit their particular needs and in ways that help them feel at ease and comfortable with the tape.

Finally, Smith and Holmes (2004) reported that golfers in a video or audio group performed significantly better than golfers in a written script or control group. This is significant because the great majority of imagery interventions in published studies have used written scripts, which now do not appear to be optimally effective. So the modality in which the imagery is presented appears to be important and should provide the participant with the most accurate motor representation of the skill (Holmes & Collins, 2001).

Include Execution and Outcome

Imagery should include both the execution and end result of skills. Many athletes image the execution of the skill and not the outcome, or vice versa. Athletes need to be able to feel the movement and control the image so that they see the desired outcome. For instance, divers must first be able to feel their body in different positions throughout a dive. Then they should see themselves making a perfectly straight entry into the water. An interesting study (Caliari, 2008) found that focusing on the movement directly related to the movement technique (e.g., the trajectory of the racket when playing tennis) produced significantly better performance than focusing on a more distant effect (e.g., the trajectory of the ball after hitting it in tennis). Therefore, athletes in sports requiring the use of an implement (e.g., baseball, tennis, golf, hockey) should focus their imagery more on the movement itself than the direction of the ball, which is external to the movement itself. Athletes should still include the outcome of their performance in their imagery; but it is most important to focus on the process with imagery.

Image Timing

From a practical and intuitive perspective, it would make sense to image in real time. In other words, the time spent imaging a particular skill should be equal to the time it takes for the skill to be executed in actuality. If a golfer normally takes 20 seconds to perform a preshot routine before putting, then his imaging of this routine should also take 20 seconds. Imaging in real time makes the transfer from imagery to real life easier. Research reveals that overall, athletes do voluntarily choose real-time imagery over fast and slow imagery (O & Hall, 2009). This is consistent with the model of Holmes and Collins (2001) mentioned earlier, which argues that “if motor preparation and execution and motor imagery access the same motor representation then the temporal characteristics should be the same” (p. 73). However, caution may be warranted, as recent research (O & Munroe-Chandler, 2008) did not show any performance differences between slow-motion and regular-speed imagery. According to these authors, this might have been because the task was novel, as slow motion might be more beneficial for a beginner trying to get the idea of the movement. A final variable to consider in relation to image timing is closed versus open skills. Specifically, research (Munzert, 2008) indicates that keeping real and imagined movements similar is more important for closed tasks (where the timing is under the athlete’s control and not affected by the opponent, as in golf, figure skating, and gymnastics) than for open tasks (e.g., football, basketball), in which the length (and exact movement patterns) of a play might be affected by actions of the opponent.

The Content of Imagery Use in Youth Sport

Munroe-Chandler, Hall, Fishburne, O, and Hall (2007) investigated the use of imagery in young athletes ranging in age from 7 to 14. In general, five different categories of imagery were found.

Some differences emerged among the different age groups, including these:

When to Use Imagery

Imagery can be used virtually any time—before and after practice, before and after competition, during the off-season, during breaks in the action in both practice and competition, during personal time, and during recovery from injury. In the following sections we describe how imagery can be used during each of these times.

Before and After Practice

One way to schedule imagery systematically is to include it before and after each practice session. Limit these sessions to about 10 minutes; most athletes have trouble concentrating any longer than this on imagery (Murphy, 1990). To focus concentration and get ready before practice, athletes should visualize the skills, routines, and plays they expect to perform. After each practice they should review the skills and strategies they worked on. Tony DiCicco, former coach of the U.S. Women’s Soccer national team, used imagery after practice to help build confidence with the following scenario:

Imagine in your mind when you do well. If you’re a great header, visualize yourself winning headers. If you’re a great defender, visualize yourself stripping the ball from an attacking player. If you’re a great passer of the ball, visualize yourself playing balls in. If you’ve got great speed, visualize yourself running by players and receiving the ball. Visualize the special skills that separate you from the rest—the skills that make your team better because you possess them. (DiCicco, Hacker, & Salzberg, 2002, p. 112)

Before and After Competition

Imagery can help athletes focus on the upcoming competition if they review exactly what they want to do, including different strategies for different situations. Optimal timing of this precompetition imagery differs from one person to another: Some athletes like to visualize right before the start of a competition, whereas others prefer doing so an hour or two before. What’s important is that the imaging fit comfortably into the pre-event routine. It should not be forced or rushed. After competition, athletes can replay the things they did successfully and get a vivid, controllable image.

Similarly, students in physical education classes can imagine themselves correcting an error in the execution of a skill they just learned and practiced. They can also replay unsuccessful events, imagining performing successfully or choosing a different strategy. Imagery can also be used to strengthen the blueprint and muscle memory of those skills already performed well. Hall of Famer Larry Bird was a great shooter, but he still practiced his shooting every day. Good performance of a particular skill does not preclude the use of imaging; the usefulness of imagery continues as long as one is performing one’s skill.

During the Off-Season

The lines between season and off-season are often blurred. In many cases, there is no “true” off-season, because athletes do cardiovascular conditioning, lift weights, and train sport-specific skills during time away from their sport. Using imagery during the off-season is a good opportunity to stay “in practice” with imaging, although recent research has revealed that athletes’ use of imagery is significantly less during this time than during the season.

During Breaks in the Action

Most sporting events have extended breaks in the action during which an athlete can use imagery to prepare for what’s ahead. In many sports there is a certain amount of “dead time” after an athlete performs, and this is an ideal opportunity to use imagery.

During Personal Time

Athletes can use imagery at home or in any other appropriate quiet place. It may be difficult to find a quiet spot before practicing, and there may be days when an athlete does not practice at all. In such cases athletes should try to set aside 10 minutes at home so that they do not break their imagery routine. Some people like to image before they go to sleep; others prefer doing it when they wake up in the morning.

How Various Professionals Use Imagery

As we have seen, imagery can be used in all sports and activities. The following are examples of how coaches and sport professionals in several activities can use imagery to enhance performance:

When Recovering From Injury

Athletes have been trained to use imagery with relaxation exercises to reduce anxiety about an injury. They have used imagery to rehearse performance as well as the emotions they anticipate experiencing on return to competition, thereby staying sharp and ready for return. Positive images of healing or full recovery have been shown to enhance recovery. Ievleva and Orlick (1991) found that positive healing and performance imagery were related to faster recovery times. (Similarly, terminally ill cancer patients have used imagery to see themselves destroying and obliterating the cancerous cells. In a number of cases, the cancer has reportedly gone into remission; see Simonton, Matthews-Simonton, & Creighton, 1978.) Imagery can also help athletes, such as long-distance runners, fight through a pain threshold and focus on the race and technique instead of on their pain. Finally, different types of imagery have been shown to be effective at different parts of the rehabilitation process (Hare, Evans, & Callow, 2008).

Learning Aids

Summary

1. Define imagery.

Imaging refers to creating or recreating an experience in the mind. A form of simulation, it involves recalling from memory pieces of information that are stored there regarding all types of experiences and shaping them into meaningful images. The image should optimally involve all the senses and not rely totally on the visual.

2. Discuss the effectiveness of imagery in enhancing sport performance.

Using anecdotal, case study, and experimental methods, researchers have found that imagery can improve performance in a variety of sports and in different situations. Of course, the principles of the effective use of imagery would need to be incorporated into imagery studies to maximize imagery effectiveness.

3. Discuss the where, when, why, and what of imagery use by athletes.

Imagery is used at many different times but most typically before competition. Categories of imagery that athletes use include cognitive general (e.g., using strategy), cognitive specific (e.g., using skills), motivational specific (e.g., receiving a medal), motivational general—arousal (arousal or relaxation), and motivational general—mastery (building confidence). Athletes image internally and externally; image positive and negative events or their surroundings; and use the visual, kinesthetic, olfactory, and auditory senses.

4. Discuss the factors influencing imagery effectiveness.

Consistent with the interactional theme that is prominent throughout this text, the effectiveness of imagery is influenced by both situational and personal factors. These include the nature of the task, the skill level of the performer, and the imaging ability of the person.

5. Describe how imagery works.

A number of theories or explanations address how imagery works. These include the psychoneuromuscular theory, symbolic learning theory, bioinformational theory, triple code theory, and psychological explanations. All five explanations have some support from research findings, and they basically propose that physiological and psychological processes account for the effectiveness of imagery.

6. Discuss the uses of imagery.

Imagery has many uses, including enhancing motivation, reducing anxiety, building confidence, enhancing concentration, recovering from injury, solving problems, and practicing specific skills and strategies.

7. Explain how to develop a program of imagery training.

Motivation and realistic expectations are critical first steps in setting up a program of imagery training. In addition, evaluation, using an instrument such as the Sport Imagery Questionnaire, should occur before the training program begins. Basic training in imagery includes exercises in vividness and controllability. Athletes should initially practice imagery in a quiet setting and in a relaxed, attentive state. They should focus on developing positive images, although it is also useful occasionally to visualize failures in order to develop coping skills. Both the execution and outcome of the skill should be imaged, and imaging should occur in real time.

8. Explain when to use imagery.

Imagery can be used before and after practice and competition, during the off-season, during breaks in the action, during personal time. Imagery can also benefit the injury rehabilitation process.

Key Terms

imagery

kinesthetic sense

visual sense

auditory sense

tactile sense

olfactory sense

anecdotal reports

case studies

multiple-baseline case studies

psychological intervention packages

scientific experiments

internal imagery

external imagery

psychoneuromuscular theory

ideomotor principle

symbolic learning theory

bioinformational theory

triple code model

psychological explanations

attention–arousal set

vividness

controllability

exercise imagery

Review Questions

1. What is imagery? Discuss recreating experiences that involve all the senses.

2. What are three uses of imagery? Provide practical examples for each.

3. Compare and contrast the psychoneuromuscular and symbolic learning theories as they pertain to imagery.

4. Describe some anecdotal and some experimental evidence supporting the effectiveness of imagery in improving performance, including evidence relating to the nature of the task and ability level.

5. Compare and contrast internal imagery and external imagery and their effectiveness.

6. Describe two exercises each to improve vividness and controllability of imagery.

7. What is the importance of vividness and controllability in enhancing the quality of imagery?

8. Discuss three of the basic elements of a successful imagery program, including why they are impor-tant.

9. Discuss when and where imagery is most often used.

10. Compare and contrast the different types of imagery including cognitive general, cognitive specific, motivational specific, motivational general—arousal, and motivational general—mastery.

11. Discuss the important factors that have been shown to influence the effectiveness of imagery.

12. Describe three potential negative outcomes of using imagery.

13. List five different functions of exercise imagery.

Critical Thinking Questions

1. Think of a sport or physical activity you enjoy (or used to enjoy). If you were to use imagery to help improve your performance as well as enhance the experience of your participation, how would you put together an imagery training program for yourself? What would be the major goals of this program? What factors would you have to consider to enhance the effectiveness of your imagery?

2. As an exercise leader you want to use imagery with a class, but the students are skeptical of its effectiveness. Using anecdotal, case study, and experimental evidence, convince students that imagery would be a great way to make the class experiences more positive.

3. As a coach, how might you use the five different types of imagery discussed in this chapter for different situations to enhance the performance, affect, and thoughts of your athletes?