After reading this chapter, you should be able to

1. understand how to increase self-awareness of arousal states,

2. use somatic, cognitive, and multimodal anxiety reduction techniques,

3. identify coping strategies to deal with competitive stress,

4. describe on-site relaxation tips to reduce anxiety,

5. understand the matching hypothesis, and

6. identify techniques to raise arousal for competition.

We live in a world where stress has become part of our daily lives. Certainly the pressure to perform at high levels in competitive sport has increased in recent years with all the media attention and money available through sport. In essence, our society values winning and success at all levels of competition, and coaches and athletes feel pressure to be successful. People who don’t cope effectively with the pressure of competitive sport, however, may experience not only decreases in performance but also mental distress and even physical illness. Continued pressure sometimes causes burnout in sport and exercise (see chapter 21), and it can lead to ulcers, migraine headaches, and hypertension. Depending on the person and the situation, however, there are various ways of coping with the pressure of competitive sport. The following quotes show how a few athletes have approached the pressure of competition.

The thing that always worked best for me whenever I felt I was getting too tense to play good tennis was to simply remind myself that the worst thing—the very worst thing that could happen to me—was that I’d lose a bloody tennis match. That’s all!

—Rod Laver, former top professional tennis player (Tarshis, 1977, p. 87)

I love the pressure. I just look forward to it.

—Daly Thompson, Olympic decathlon gold medalist

The relaxation technique that I have adopted over the past year is a type of mantra. I count down from three to zero, and when I get to zero I can produce a calmer approach. I use this if I have to stand there and wait around for the judges and I feel a rush of nervousness that’s too much.

—James May, Commonwealth Games gymnastics gold medalist

Not only do athletes respond differently to pressure, but the type of sport or task they perform also becomes a critical factor in how they react. For example, a golfer preparing to knock in a 20-foot putt would control arousal differently than would a wrestler taking the mat. Similarly, one specific relaxation procedure might work better for controlling cognitive (mental) anxiety, whereas another might be more effective for coping with somatic (perceived physiological) anxiety. The relation between arousal and performance can be complicated (see chapter 4), and athletes in competitive sport need to learn to control their arousal. They should be able to increase it—to psych up—when they’re feeling lethargic and to decrease it when the pressure to win causes them anxiety and nervousness. The key is for individuals to find their optimal levels of arousal without losing intensity and focus. In this chapter we discuss in detail a variety of arousal regulation techniques that should help individuals in sport and exercise settings reach their optimal levels of arousal. The first step in this process is to learn how to recognize or become aware of anxiety and arousal states.

Increasing Self-Awareness of Arousal

The first step toward controlling arousal levels is to be more aware of them during practices and competitions. This typically involves self-monitoring and recognizing how emotional states affect performance. As an athlete you can probably identify certain feelings associated with top performances and other feelings associated with poor performances. To increase awareness of your arousal states, we recommend the following process.

First, think back to your best performance. Try to visualize the actual competition as clearly as possible, focusing on what you felt and thought at that time. Take at least 5 minutes to relive the experience. Now complete the items in the “Checklist of Performance States.” Because you are reconstructing your best performance, for “played extremely well,” you would circle the number 1. For the second item, if you felt moderately anxious, you might circle number 4. After completing the checklist for your best performance, repeat the process for your worst performance.

Now compare your responses in this exercise between the two performances you brought to mind. Most people find that their thoughts and feelings are distinctly different when comparing playing well and playing poorly. This is the beginning of awareness training. If you want to better understand the relation between your thoughts, feelings, and performance, monitor yourself by completing the checklist immediately after each practice or competitive session over the next few weeks. Of course, your psychological state will vary during a given session. If you feel one way during the first half of a basketball game, for example, and another way during the second half, simply complete two checklists.

In a relatively recent development, the study of the self-awareness of arousal states has started to focus on whether these states are felt as facilitative or debilitative. Olympic basketball coach Jack Donahue noted that “it’s not a case of getting rid of the butterflies, it’s a question of getting them to fly in formation” (Orlick, 1986, p. 112). Along these lines, it has been found that elite athletes generally interpret their anxiety as more facilitative than non-elite athletes (Hanton & Jones, 1999a). Sport psychologists can help athletes not only become more aware of their arousal states but also interpret them in a positive manner. This is seen in the following quote by an Olympic swimmer:

I mean you have to get nervous to swim well…. If you’re not bothered about it, you are not going to swim well…. I think the nerves bring out the best in you and I soon realized that I wanted to feel this way. (Hanton & Jones, 1999b, p. 9)

In addition, Eubank and Collins (2000) found that individuals who see their anxiety as facilitative are more likely to use both problem-focused and emotion-focused coping. Conversely, individuals viewing their anxiety as debilitative appeared limited in their use of any coping strategies. So not only do people who perceive their anxiety as facilitative typically perform better; they also cope more effectively with the anxiety. Let’s now turn to some of the more popular anxiety reduction techniques in sport and exercise settings.

Using Anxiety Reduction Techniques

One important way in which excess anxiety can affect performers is through increased muscle tension. In fact, excess anxiety can produce inappropriate muscle tension, which in turn can diminish performance. And it is all too easy to develop excess muscle tension. The common thinking is, “The harder you try, the better you will perform.” This reasoning, however, is incorrect.

As a quick, practical exercise, rest your dominant forearm and hand palm down on a desktop or table. Tense all the muscles in your hand and wrist and then try to tap your index and middle fingers quickly back and forth. Do this for about 30 seconds. Now try to relax the muscles in your hands and fingers and repeat the exercise. You will probably discover that muscular tension slows your movements and makes them less coordinated, compared with movements of muscles that are relaxed.

Besides sometimes producing inappropriate muscle tension, excess anxiety can produce inappropriate thoughts and cognitions such as, “I hope I don’t blow this shot” or “I hope I don’t fail in front of all these people.” A quote by baseball player B.J. Surhoff makes this point: “The power has always been there; I just had to find a way to tap it…. Mostly, it’s a matter of learning to relax at the plate. You don’t worry about striking out and looking bad as much as before.”

In addition to simply reducing anxiety, as noted in chapter 4, it is important to interpret anxiety in a facilitative as compared to a debilitative manner. Research (Thomas, Hanton, & Maynard, 2007) revealed that three time periods were critical in the interpretation of anxiety: (a) post-performance (previous performance), (b) 1 or 2 days prior to competition, and (c) day of competition. In each of these time frames, facilitators utilized a refined repertoire of psychological skills (e.g., imagery, reframing self-talk) to internally control and reinterpret the cognitive and somatic anxiety experienced. Conversely, debilitators did not possess these refined psychological skills and therefore lacked internal control to alter their anxiety states.

We now present some relaxation procedures commonly used in sport and physical activity settings. Some of these techniques focus on reducing somatic anxiety, some on cognitive anxiety. Still others are multimodal in nature, using a variety of techniques to cope with both somatic and cognitive anxiety.

Somatic Anxiety Reduction Techniques

The first group of techniques works primarily to reduce physiological arousal associated with increased somatic anxiety.

Progressive Relaxation

Edmund Jacobson’s progressive relaxation technique (1938) forms the cornerstone for many modern relaxation procedures. This technique involves tensing and relaxing specific muscles. Jacobson named the technique progressive relaxation because the tensing and relaxing progress from one major muscle group to the next until all muscle groups are completely relaxed. Progressive relaxation rests on a few assumptions: (a) It is possible to learn the difference between tension and relaxation; (b) tension and relaxation are mutually exclusive—it is not possible to be relaxed and tense at the same time; and (c) relaxation of the body through decreased muscle tension will, in turn, decrease mental tension. Jacobson’s technique has been modified considerably over the years, but its purpose remains that of helping people learn to feel tension in their muscles and then let go of this tension.

The tension–relaxation cycles develop an athlete’s awareness of the difference between tension and lack of tension. Each cycle involves maximally contracting one specific muscle group and then attempting to fully relax that same muscle group, all the while focusing on the different sensations of tension and relaxation. With skill, an athlete can detect tension in a specific muscle or area of the body, like the neck, and then relax that muscle. Some people even learn to use the technique during breaks in an activity, such as a time-out. The first few sessions of progressive relaxation take an athlete up to 30 minutes. With practice, less time is necessary, the goal being to develop the ability to relax on-site during competition.

Ost (1988) developed an applied variant of relaxation technique that he based on progressive relaxation to teach an individual to relax even within 20 to 30 seconds. The first phase of training involves a 15-minute progressive relaxation session practiced twice a day, in which muscle groups are tensed and relaxed. The individual then moves on to a release-only phase that takes 5 to 7 minutes to complete. The time is next reduced to a 2- to 3-minute version with the use of a self-instructional cue, “Relax.” This time is further reduced until only a few seconds are required, and then the technique is practiced in specific situations. For example, a golfer who becomes tight and anxious when faced with important putts could use this technique in between shots to prepare for difficult putts.

Breath Control

Proper breathing is often considered key to achieving relaxation, and breath control is another physically oriented relaxation technique. Breath control, in fact, is one of the easiest, most effective ways to control anxiety and muscle tension. When you are calm, confident, and in control, your breathing is likely to be smooth, deep, and rhythmic. When you’re under pressure and tense, your breathing is more likely to be short, shallow, and irregular.

Unfortunately, many athletes have not learned proper breathing. Performing under pressure, they often fail to coordinate their breathing with the performance of the skill. Research has demonstrated that breathing in and holding your breath increases muscle tension, whereas breathing out decreases muscle tension. For example, most discus throwers, shot-putters, and baseball pitchers learn to breathe out during release. As pressure builds in a competition, the natural tendency is to hold one’s breath, which increases muscle tension and interferes with the coordinated movement necessary for maximum performance. Taking a deep, slow, complete breath usually triggers a relaxation response.

To practice breath control, take a deep, complete breath, and imagine that the lungs are divided into three levels. Focus on filling the lower level of the lungs with air, first by pushing the diaphragm down and forcing the abdomen out. Then fill the middle portion of the lungs by expanding the chest cavity and raising the rib cage. Finally, fill the upper level of the lungs by raising the chest and shoulders slightly. Hold this breath for several seconds and then exhale slowly by pulling the abdomen in and lowering the shoulders and chest. By focusing on the lowering (inhalation) and raising (exhalation) of the diaphragm, you’ll experience an increased sense of stability, centeredness, and relaxation. To help enhance the importance and awareness of the exhalation phase, people can learn to inhale to a count of four and exhale to a count of eight. This 1:2 ratio of inhalation to exhalation helps slow breathing and deepens the relaxation by focusing on the exhalation phase.

The best time to use breath control during competition is during a time-out or break in the action (e.g., before serving in tennis, just before putting a golf ball, preparing for a free throw in basketball). The slow and deliberate inhalation–exhalation sequence will help you maintain composure and control over your anxiety during particularly stressful times. By focusing on your breathing, you are less likely to be bothered by irrelevant cues or distractions, as well as relaxing shoulder and neck muscles. Finally, deep breathing provides a short mental break from the pressure of competition and can renew your energy.

Instructions for Progressive Relaxation

In each step you’ll first tense a muscle group and then relax it. Pay close attention to how it feels to be relaxed as opposed to tense. Each phase should take about 5 to 7 seconds. For each muscle group, perform each exercise twice before progressing to the next group. As you gain skill, you can omit the tension phase and focus just on relaxation. It is usually a good idea to record the following instructions; you might even invest a few dollars in buying a progressive relaxation recording.

1. Find a quiet place, dim the lights, and lie down in a comfortable position with your legs uncrossed. Loosen tight clothing. Take a deep breath, let it out slowly, and relax.

2. Raise your arms, extend them in front of you, and make a tight fist with each hand. Notice the uncomfortable tension in your hands and fingers. Hold that tension for 5 seconds; then let go halfway and hold for an additional 5 seconds. Let your hands relax completely. Notice how the tension and discomfort drain from your hands, replaced by comfort and relaxation. Focus on the contrast between the tension you felt and the relaxation you now feel. Concentrate on relaxing your hands completely for 10 to 15 seconds.

3. Tense your upper arms tightly for 5 seconds and focus on the tension. Let the tension out halfway and hold for an additional 5 seconds, again focusing on the tension. Now relax your upper arms completely for 10 to 15 seconds and focus on the developing relaxation. Let your arms rest limply at your sides.

4. Curl your toes as tight as you can. After 5 seconds, relax the toes halfway and hold for an additional 5 seconds. Now relax your toes completely and focus on the spreading relaxation. Continue relaxing your toes for 10 to 15 seconds.

5. Point your toes away from you and tense your feet and calves. Hold the tension hard for 5 seconds; then let it out halfway for another 5 seconds. Relax your feet and calves completely for 10 to 15 seconds.

6. Extend your legs, raising them about 6 inches off the floor, and tense your thigh muscles. Hold the tension for 5 seconds, let it out halfway, and hold for another 5 seconds before relaxing your thighs completely. Concentrate on your feet, calves, and thighs for 30 seconds.

7. Tense your stomach muscles as tight as you can for 5 seconds, concentrating on the tension. Let the tension out halfway and hold for an additional 5 seconds before relaxing your stomach muscles completely. Focus on the spreading relaxation until your stomach muscles are completely relaxed.

8. To tighten your chest and shoulder muscles, press the palms of your hands together and push. Hold for 5 seconds; then let go halfway and hold for another 5 seconds. Now relax the muscles and concentrate on the relaxation until your muscles are completely loose and relaxed. Concentrate also on the muscle groups that have been previously relaxed.

9. Push your back to the floor as hard as you can and tense your back muscles. Let the tension out halfway after 5 seconds, hold the reduced tension, and focus on it for another 5 seconds. Relax your back and shoulder muscles completely, focusing on the relaxation spreading over the area.

10. Keeping your torso, arms, and legs relaxed, tense your neck muscles by bringing your head forward until your chin digs into your chest. Hold for 5 seconds, release the tension halfway and hold for another 5 seconds, and then relax your neck completely. Allow your head to hang comfortably while you focus on the relaxation developing in your neck muscles.

11. Clench your teeth and feel the tension in the muscles of your jaw. After 5 seconds, let the tension out halfway and hold for 5 seconds before relaxing. Let your mouth and facial muscles relax completely, with your lips slightly parted. Concentrate on totally relaxing these muscles for 10 to 15 seconds.

12. Wrinkle your forehead and scalp as tightly as you can, hold for 5 seconds, and then release halfway and hold for another 5 seconds. Relax your scalp and forehead completely, focusing on the feeling of relaxation and contrasting it with the earlier tension. Concentrate for about a minute on relaxing all of the muscles of your body.

13. Cue-controlled relaxation is the final goal of progressive relaxation. Breathing can serve as the impetus and cue for effective relaxation. Take a series of short inhalations, about one per second, until your chest is filled. Hold for 5 seconds; then exhale slowly for 10 seconds while thinking to yourself the word relax or calm. Repeat the process at least five times, each time striving to deepen the state of relaxation that you’re experiencing.

Biofeedback

Biofeedback is a physically oriented technique specifically designed to teach people to control physiological or autonomic responses. It usually involves an electronic monitoring device that can detect and amplify internal responses not ordinarily known to us. These electronic instruments provide visual or auditory feedback of physiological responses such as muscle activity, skin temperature, brain waves, or heart rate, although most studies have used muscle activity as measured by electromyography (Zaichkowsky & Takenaka, 1993).

For example, a tennis player might feel muscle tension in her neck and shoulders before serving on important points in a match. Electrodes could be attached to specific muscles in her neck and shoulder region, and she would be asked to relax these specific muscles. Excess tension in the muscles would then cause the biofeedback instrument to make a loud and constant clicking noise. The tennis player’s goal would be to quiet the machine by attempting to relax her shoulder and neck muscles. She could accomplish relaxation through any relaxation technique, such as visualizing a positive scene or using positive self-talk. The key point is that the lower the noise level, the more relaxed the muscles are. Such feedback attunes the player to her tension levels and whether they are decreasing or increasing.

Once the tennis player learns to recognize and reduce muscle tension in her shoulders and neck, she needs to be able to transfer this knowledge to the tennis court. She can do this by interspersing sessions of nonfeedback (time away from the biofeedback device) within the training regimen. Gradually, the duration of these nonfeedback sessions is increased, and the tennis player depends less on the biofeedback signal while maintaining an awareness of physiological changes. With sufficient practice and experience, the tennis player can learn to identify the onset of muscle tension and control it so that her serve remains effective in clutch situations.

Research has indicated that rifle shooters can improve their performance by training themselves, using biofeedback, to fire between heartbeats (Daniels & Landers, 1981; Wilkinson, Landers, & Daniels, 1981). In addition, biofeedback has been effective for improving performance among recreational, collegiate, and professional athletes in a variety of sports (Crews, 1993; Zaichkowsky & Fuchs, 1988, 1989). Although not all studies of biofeedback have demonstrated enhanced performance, the technique has been shown to consistently reduce anxiety and muscle tension.

Cognitive Anxiety Reduction Techniques

Some relaxation procedures focus more directly on relaxing the mind than do progressive relaxation and deep breathing. The argument is that relaxing the mind will in turn relax the body. Both physical and mental techniques can produce a relaxed state, although they work through different paths. We next discuss some of the techniques for relaxing the

mind.

Relaxation Response

Herbert Benson, a physician at Harvard Medical School, popularized a scientifically sound way of relaxing that he called the relaxation response (Benson & Proctor, 1984). Benson’s method applies the basic elements of meditation but eliminates any spiritual or religious significance. Many athletes have used meditation to mentally prepare for competition, asserting that it improves their ability to relax, concentrate, and become energized. However, few controlled studies have addressed the effectiveness of the relaxation response in enhancing performance. The state of mind produced by meditation is characterized by keen awareness, effortlessness, relaxation, spontaneity, and focused attention—many of the same elements that characterize peak performance. The relaxation response requires four elements:

1. A quiet place, which ensures that distractions and external stimulation are minimized.

2. A comfortable position that can be maintained for a while. Sit in a comfortable chair, for example, but do not lie down in bed—you do not want to fall asleep.

3. A mental device, which is the critical element in the relaxation response, that involves focusing your attention on a single thought or word and repeating it over and over. Select a word, such as relax, calm, or easy, that does not stimulate your thoughts, and repeat the word while breathing out. Every time you exhale, repeat your word.

4. A passive attitude, which is important but can be difficult to achieve. You have to learn to let it happen, allowing the thoughts and images that enter your mind to move through as they will, making no attempt to attend to them. If something comes to mind, let it go and refocus on your word. Don’t worry about how many times your mind wanders; continue to refocus your attention on your word.

Learning the relaxation response takes time. You should practice it about 20 minutes a day. You will discover how difficult it is to control your mind and focus on one thought or object. But staying focused on the task at hand is important to many sports. The relaxation response teaches you to quiet the mind, which will help you to concentrate and reduce muscle tension. However, it is not an appropriate technique to use right before an event or competition. Finally, it should be noted that studies using meditation (which is related to the relaxation response in that a key component is focusing on repetition of a sound) have demonstrated lower lactate levels, less self-reported tension, and increases in performance compared to control conditions (Solberg et al., 1996, 2000).

Autogenic Training

Autogenic training consists of a series of exercises designed to produce sensations, specifically of warmth and heaviness. Used extensively in Europe but less in North America, the training was developed in Germany in the early 1930s by Johannes Schultz and later refined by Schultz and Luthe (1969). Basically, it is a technique of self-hypnosis, thus a mental technique. Attention is focused on the sensations you are trying to produce. As in the relaxation response, feeling should be allowed to happen without interference. The autogenic training program is based on six hierarchical stages, which should be learned in order:

1. Heaviness in the extremities

2. Warmth in the extremities

3. Regulation of cardiac activity

4. Regulation of breathing

5. Abdominal warmth

6. Cooling of the forehead

The statements “My right arm is heavy,” “My right arm is warm and relaxed,” “My heartbeat is regular and calm,” “My breathing rate is slow, calm, and relaxed,” and “My forehead is cool” are all examples of commonly used verbal stimuli in autogenic training. It usually takes several months of regular practice, 10 to 40 minutes a day, to become proficient, to experience heaviness and warmth in the limbs, and to produce the sensation of a relaxed, calm heartbeat and respiratory rate accompanied by warmth in the abdomen and coolness in the forehead.

An Example of Successful Relaxation Training

An elite racket sport player (who had won numerous international championships) sought out a sport psychologist to help her cope with her propensity to panic under pressure—that is, when the score was close at the end of a match. The following is an overview of the relaxation training that sport psychologist (Jones, 1993) provided. Note that this relaxation training method is similar to one that Ost (1988) presented, except that the relaxation response, rather than progressive relaxation, serves as the starting point.

Phase 1

This initial phase involved about 20 minutes of taped instructions in which the athlete generally learned the relaxation response. This included (a) concentrating on breathing, (b) using a mental device (repeating the word one or some other single-syllable word such as ease) on each exhalation, (c) listening to relaxing music, (d) counting down from 10 to 1 on each exhalation, and (e) counting up from 1 to 7 on each inhalation. After two sessions of this form of relaxation in the presence of the sport psychologist, the athlete practiced using the tape at least once daily for the next 2 weeks, finally being able to achieve a deep state of relaxation.

Phase 2

In this phase, the period of relaxation was reduced to approximately 5 minutes. In this version the athlete continued to listen to the taped instructions, but the music was excluded and the mental device of one was changed to relax. In addition, the counting procedure was changed to counting down from 5 to 1 and then up from 1 to 3. The athlete practiced this every day for 2 weeks, using the 20-minute tape twice a week. During the second week, the athlete also practiced the 5-minute relaxation without the aid of the tape. By the end of the second week the athlete was proficient at reaching the desired level of relaxation without the tape.

Phase 3

In this phase, the athlete concentrated on each inhalation and silently said relax to herself on each exhalation. The sport psychologist had the athlete think about various physically taxing, uncomfortable situations (e.g., shuttle runs to exhaustion) in which she was asked to relax as best she could. While she did this, the relaxation technique was reduced to approximately 5 to 20 seconds, requiring four or five breaths. The athlete was now practicing three versions of the original relaxation technique: (a) the 20-minute version used for deep relaxation, but not to be used on match days; (b) the 5-minute version, which was used for gaining composure and could be used on competition days; and (c) the “quick” version, which required only a few seconds and could be used on court to maintain composure.

Phase 4

The athlete practiced the quick relaxation technique as much as possible during practice situations and practice matches. The athlete used a cue to trigger her quick relaxation, which was simply to focus on the trademark on her racket and to relax as she walked across court to either serve or receive serve. She then used this technique in competitive matches when she played a poor shot or just before she played a critical point.

Multimodal Anxiety Reduction Packages

The anxiety reduction techniques just presented focus on either the cognitive or the somatic aspects of anxiety. Multimodal stress management packages, however, can alleviate both cognitive and somatic anxiety while providing systematic strategies for the rehearsal of coping procedures under simulated stressful conditions. The two most popular ones are cognitive–affective stress management training, developed by Ronald Smith (1980), and stress inoculation training, developed by Donald Meichenbaum (1985). A key feature of these techniques is that they help athletes develop a number of different coping skills to manage a wide variety of problems emanating from different stressful situations. Thus, these coping skills training programs help athletes control dysfunctional emotions by producing more adaptive appraisals, improving coping responses, and increasing confidence to use their coping skills to manage numerous sources of athletic stress.

Cognitive–Affective Stress Management Training

Cognitive–affective stress management training (SMT) is one of the most comprehensive stress management approaches. Stress management training is a skills program designed to teach a person a specific integrated coping response using relaxation and cognitive components to control emotional arousal. Bankers, business executives, social workers, and college administrators have all applied SMT, and athletes have also found this technique to be effective (Crocker, Alderman, Murray, & Smith, 1988). Athletes have proved to be an ideal target population: They acquire the coping skills (e.g., muscular relaxation) somewhat more quickly than other groups, face stressful athletic situations frequently enough to permit careful monitoring of their progress, and perform in ways that can be readily assessed.

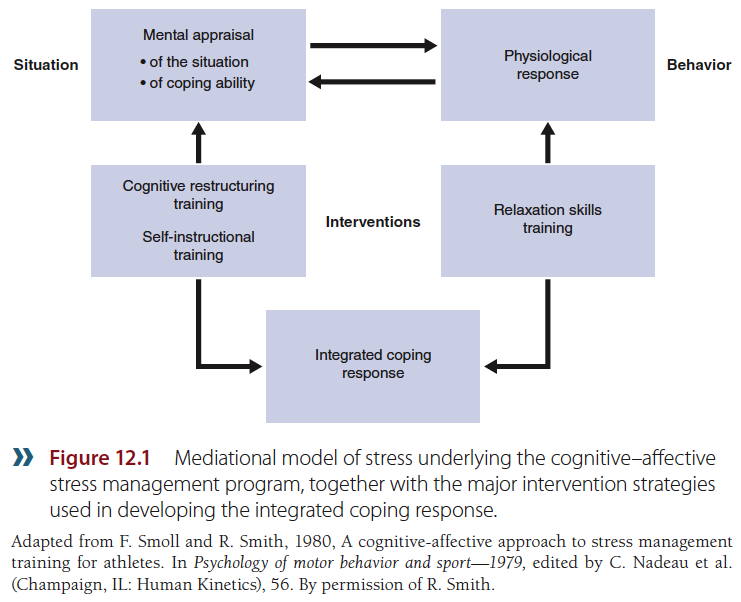

The theoretical model of stress underlying SMT (see figure 12.1) includes both cognitively based and physiologically based intervention strategies (derived from the work of Ellis, 1962; Lazarus, 1966; and Schachter, 1966). This model accounts for the situation, the person’s mental appraisal of the situation, the physiological response, and the actual behavior. The program offers specific intervention strategies, such as relaxation skills, cognitive restructuring, and self-instructional training, to help deal with the physical and mental reactions to stress. Combining mental and physical coping strategies eventually leads to an integrated coping response.

Smith’s cognitive–affective SMT program has four separate phases:

1. Pretreatment assessment. During this phase, the consultant conducts personal interviews to assess the kinds of circumstances that produce stress, the player’s responses to stress, and the ways in which stress affects performance and other behaviors. The consultant also assesses the player’s cognitive and behavioral skills and deficits and administers written questionnaires to supplement the interview. This information is used to tailor a program to the player.

2. Treatment rationale. During the treatment rationale phase, the idea is to help the player understand his stress response by analyzing personal stress reactions and experiences. The consultant should emphasize that the program is educational, not psychotherapeutic, in design, and participants should understand that the program is intended to increase their self-control.

3. Skill acquisition. The major objective of the SMT program is to develop an integrated coping response (see figure 12.1) by acquiring both relaxation and cognitive intervention skills. In the skill acquisition phase, participants receive training in muscular relaxation, cognitive restructuring, and self-instruction. The muscular relaxation comes from progressive relaxation. Cognitive restructuring is the attempt to identify irrational or stress-inducing self-statements, which are typically related to the fear of failure and disapproval (e.g., “I know I’ll mess up,” “I couldn’t stand to let my teammates and coaches down”). These statements are then restructured into more positive thoughts (e.g., “I’ll still be a good person whether I win or lose,” “Don’t worry about losing—just play one point at a time”). Changing negative self-statements into positive self-statements is discussed in more detail in chapter 16. Self-instructional training teaches people to provide themselves with specific instructions to improve concentration and problem solving. This training teaches specific, useful self-commands, especially helpful for stressful situations. Examples of such commands might be “Don’t think about fear, just think about what you have to do,” “Take a deep breath and relax,” and “Take things one step at a time, just like in practice.”

4. Skill rehearsal. To facilitate the rehearsal process, the consultant intentionally induces different levels of stress (typically by using films, imaginary rehearsals of stressful events, and other physical and psychological stressors), even high levels of emotional arousal that exceed those in actual competitions (Smith, 1980). These arousal responses are then reduced through the use of coping skills that the participant has acquired. The procedure of induced affect can produce high levels of arousal, so only trained clinicians should use this component of the technique.

Stress Inoculation Training

One of the most popular multifaceted stress management techniques used both inside and outside the sport environment is stress inoculation training (SIT; Meichenbaum, 1985). Recent research has found SIT to be effective in reducing anxiety and enhancing performance in sport settings (Kerr & Leith, 1993), as well as in helping athletes cope with the stress of injury (Kerr & Goss, 1996). The approach for SIT has a number of similarities to SMT, so we provide only a brief outline of SIT.

Stress inoculation training (SIT) gets its name because the individual is exposed to and learns to cope with stress in increasing amounts, thereby enhancing her immunity to stress. Stress inoculation training teaches skills for coping with psychological stressors and for enhancing performance by developing productive thoughts, mental images, and self-statements. One application of SIT has athletes break down stressful situations using a four-stage approach including (a) preparing for the stressor (e.g., “It is going to be rough; keep your cool”), (b) controlling and handling the stressor (e.g., “Keep your cool because he’s losing his cool”), (c) coping with feelings of being overwhelmed (e.g., “Keep focused: What do you have to do next?”), and (d) evaluating coping efforts (e.g., “You handled yourself well”). Through SIT, athletes are given opportunities to practice their coping skills, starting with small manageable doses of stress and progressing to greater amounts of stress. Thus, athletes develop a sense of “learned resourcefulness” by successfully coping with stressors through a variety of techniques including imagery, role-playing, and homework assignments. The use of a stage approach and the strategies of self-talk, cognitive restructuring, and relaxation make both SIT and SMT effective multimodal approaches for anxiety reduction.

Hypnosis

A somewhat controversial and often misunderstood technique for reducing anxiety (both cognitive and somatic), as well as enhancing other mental skills, is hypnosis. Although many different definitions have been put forth, hypnosis is defined here as an altered state of consciousness that can be induced by a procedure in which a person is in an unusually relaxed state and responds to suggestions for making alterations in perceptions, feelings, thoughts, or actions (Kirsch, 1994). Originally used by clinical psychologists and psychiatrists outside of sport to enhance performance, focus attention, increase confidence, and reduce anxiety, hypnosis has been increasingly used in sport contexts. Although hypnotic procedures include components used in other applied sport psychology interventions such as relaxation and imagery, they differ from other techniques because they require participants to enter a hypnotic state before other techniques (e.g., relaxation, imagery) are applied.

Earlier research by Unesthal (1986) used hypnotic techniques, but little attention was given to this work. However, more recently there has been an upsurge in the use of hypnosis as an arousal regulation technique. For example, research (Lindsay, Maynard, & Thomas, 2005; Pates, Oliver, & Maynard, 2001) revealed that hypnosis was related to feelings of peak performance states (see chapter 11) that resulted in improvements in basketball, cycling, and golf performance (greater feelings of relaxation were particularly noted by participants). In addition, Barker and Jones (2008) found that hypnosis increased positive affect and decreased negative affect in soccer. So, what are the specific stages of a hypnosis intervention?

Sport psychologists who wish to use these techniques should acquire specialized training and education from mentors with appropriate clinical qualifications and experience. Some facts about hypnosis and its effects on performance are highlighted in “Facts About Hypnosis.”

Exploring the Matching Hypothesis

You now have learned about a variety of relaxation techniques, and it is logical to ask when these techniques should be used to achieve maximum effectiveness. In attempting to answer this question, researchers have explored what is known as the matching hypothesis. This hypothesis states that an anxiety management technique should be matched to a particular anxiety problem. That is, cognitive anxiety should be treated with mental relaxation, and somatic anxiety should be treated with physical relaxation. This individualized approach is similar to the stress model developed by McGrath (see chapter 4). A series of studies (Maynard & Cotton, 1993; Maynard, Hemmings, & Warwick-Evans, 1995; Maynard, Smith, & Warwick-Evans, 1995) have provided support for the matching hypothesis.

Facts About Hypnosis

Although researchers and practitioners don’t always agree on the definition of hypnosis, they agree generally about the following aspects of hypnosis:

The studies by Maynard and his colleagues showed a somatic relaxation technique (progressive relaxation) to be more effective than a cognitive one (positive thought control) in reducing somatic anxiety. Similarly, the cognitive relaxation technique was more effective than the somatic one in reducing cognitive anxiety. The reductions in somatic and cognitive anxiety were associated with some subsequent (but not quite consistent) increases in performance. More recent research (Rees & Hardy, 2004) found this same matching hypothesis appropriate for the use of social support as a way to cope with anxiety. More specifically, certain types of social support were found to be more effective in reducing anxiety among performers. So once again, the specific social support (e.g., informational emotional) should be matched to the specific anxiety problem experienced by the athlete (e.g., competition pressure, technical problems in training) to produce maximum effectiveness in reducing anxiety.

However, “crossover” effects (whereby somatic anxiety relaxation techniques produce decreases in cognitive anxiety, and cognitive anxiety relaxation techniques produce decreases in somatic anxiety) also occurred in these studies. In one study using a cognitive relaxation technique, the intensity of cognitive anxiety decreased by 30%; the intensity of somatic anxiety also decreased, although by only 15%. Similarly, when a somatic relaxation procedure was used, the intensity of somatic anxiety decreased by 31% and the intensity of cognitive anxiety decreased as well, although by 16%. In other words, somatic relaxation techniques had some benefits for reducing cognitive anxiety, and cognitive relaxation techniques had some benefits for reducing somatic anxiety. These crossover effects have led some researchers to argue that SMT and SIT are the more appropriate programs to use, inasmuch as these multimodal anxiety reduction techniques can work on both cognitive and somatic anxiety.

Given the current state of knowledge, we recommend that if an individual’s anxiety is primarily cognitive, a cognitive relaxation technique be used. If somatic anxiety is the primary concern, focus on somatic relaxation techniques. Finally, if you are not sure what type of anxiety is most problematic, then use a multimodal technique.

Coping With Adversity

Athletes should learn a broad spectrum of coping strategies to use in different situations and for different sources of stress (Hardy, Jones, & Gould, 1996). Although athletes tend to use similar coping strategies from situation to situation, in a more traitlike manner (Giacobbi & Weinberg, 2000), it is also the case that athletes change strategies across situations. Successful athletes vary in their coping strategies, but all have skills that work when they need them most. Consider the strategies of two athletes:

[My strategy is] having tunnel vision…. I eliminate anything that’s going to interfere with me. I don’t have any side doors, I guess, for anyone to come into. I make sure that nothing interferes with me.

—Olympic wrestler (cited in Gould, Eklund, & Jackson, 1993, p. 88)

I did a lot of visualization. A lot of that…. It’s a coping strategy. It felt like you did more run-throughs. You went through the program perfectly [many] times. So, it gave you a sense of security and understanding about what was to take place and how it was supposed to go. It just gives you a calmer, more serene

way.

—U.S. national champion figure skater (cited in Gould, Finch, & Jackson, 1993, p. 458)

Although the relaxation techniques we have discussed have helped individuals reduce anxiety in sport and exercise settings, the wrestler and the figure skater demonstrate how athletes also use more specific coping strategies to help deal with potential adversity and stress in competitions. The stressors particular to competitions include the fear of injury, performance slumps, the expectations of others, crowd noises, external distractions, and critical points within the competition. Let’s first take a look at how coping is defined before discussing specific coping strategies used in sport.

Definition of Coping

Although many definitions of coping have been put forth in the psychological literature, the most popular definition is “a process of constantly changing cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage specific external and/or internal demands or conflicts appraised as taxing or exceeding one’s resources” (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984, p. 141). This view has the advantage of considering coping as a dynamic process involving both cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage stress—a definition that is consistent with McGrath’s (1970) model of stress (presented in chapter 4). In addition, it emphasizes an interactional perspective, with both personal and situational factors combining to influence the coping responses. In fact, although individuals appear to exhibit similar coping styles across situations, the particular coping strategies they use depend on both personal and situational factors (Bouffard & Crocker, 1992).

Categories of Coping

The two most widely accepted coping categories are problem-focused coping and emotion-focused coping. Problem-focused coping involves efforts to alter or manage the problem that is causing the stress for the individual concerned. It includes such specific behaviors or categories as information gathering, precompetition and competition plans, goal setting, time management skills, problem solving, increasing effort, self-talk, and adhering to an injury rehabilitation program. Emotion-focused coping entails regulating the emotional responses to the problem that causes stress for the individual. It includes such specific behaviors or categories as meditation, relaxation, wishful thinking, reappraisal, self-blame, mental and behavioral withdrawal, and cognitive efforts to change the meaning of the situation (but not the actual problem or environment). Lazarus and Folkman (1984) suggested that problem-focused coping is used more often when situations are amenable to change, and emotion-focused coping is used more often when situations are not amenable to change. Given multiple stressors (e.g., interpersonal relationships, injury, expectation of others, financial matters), there is a consensus that no single type of coping strategy is effective in all athletic settings. It is recommended, therefore, that athletes learn a diverse set of problem- and emotion-focused coping strategies to prepare them to manage emotions effectively in numerous, and sometimes novel, stress situations.

Coping With the Yips

The yips (most commonly associated with golf) is a condition that includes involuntary tremors, freezing, or jerking of the hands, most often seen in golf shots such as putting and chipping but also seen in archery (called target panic), throwing a baseball, and shooting foul shots in basketball. This condition can be devastating, especially to an elite or professional athlete as it can literally ruin a career. The yips are usually due to anxiety, nerves, or choking in high-pressure situations. For example, golfers with the yips tend to have higher heart rates, a tighter grip on the putter, and increased forearm and muscle activity. (However, the yips, although rarely, can also be a real physical condition called focal dystonia, a neurological disorder characterized by involuntary movements or spasms of small muscles.) How can athletes cope with the yips from a psychological perspective?

Studies of Coping in Sport

Compared with what we see in the general psychology literature, there is a paucity of research in sport psychology on coping, although such studies have been on the increase in the past 15 years (e.g., Anshel & Weinberg, 1995a; Crocker, 1992; Madden, 1995; Pensgaard & Duda, 2003). In fact, one of the top researchers in the world on stress and coping (Lazarus, 2000) has argued that sport provides a classic situation in which the effectiveness of different coping strategies can be tested. Along these lines, in a series of in-depth qualitative interviews, Dale (2000) and Gould, Eklund, and Jackson (1992a, 1992b) assessed the coping strategies that elite athletes use. Despite using many different strategies, at least 40% of the athletes reported using the following:

Furthermore, research by Gould and his colleagues on Olympic athletes (e.g., Gould, Guinan, Greenleaf, Medbery, & Peterson, 1999; Greenleaf, Gould, & Dieffenbach, 2001) has revealed the following consistent findings:

Virtually all of the previous research focused on short-term coping and its perceived effectiveness in reducing stress related to competition. However, Kim and Duda (2003) have also investigated the long-term effects of coping. Results revealed that both active–problem-focused coping and avoidance–withdrawal coping were effective in reducing the immediate stress of competition. But when the researchers looked at long-term variables such as satisfaction, enjoyment, and desire to continue participation in the sport, only active–problem-focused coping produced a positive relationship, whereas a negative relationship was found with avoidance–withdrawal coping. In fact, research (Giacobbi, Foore, & Weinberg, 2004) has found that non-elite athletes use avoidance coping techniques more than elite athletes, so this could be a big problem with recreational athletes. Furthermore, recent research (Nicholls, Polman, Morley, & Taylor, 2009) has found that factors such as gender, age, and pubertal status can influence both the type of coping strategy employed and its perceived effectiveness. For example, mental distraction strategies were significantly more effective for female athletes, whereas venting emotions was significantly more effective for male athletes. In addition, postpubertal athletes felt that mental distraction was more effective than athletes in the beginning or middle stage of puberty. Finally, even recent research on coping strategies within individuals has shown inconsistency rather than consistency (Nicholas & Jebrane, 2009)—specifically, inconsistency in coping within athletes between competition and practice, as well as across and within different competitive settings. In essence, coping appears to be situation specific.

Resiliency: Bouncing Back From Adversity

Most of us probably know survivors of horrific circumstances and events such as cancer, the Holocaust, HIV/AIDS, war, and the terrorist attacks of 9/11. Studies (e.g., Butler et al., 2005) have shown that many individuals not only survive, but gain positive attributes because of adversity. It has been argued that experiences of adversity serve to strengthen resilient qualities such as self-esteem and self-efficacy. The notion of resiliency seems appropriate for the study of sport because one needs to effectively bounce back from adversity in the form of injury, poor performance, being cut from a team, firing (coaches), lack of crowd or community support, and team conflicts (to name a few). Galli and Vealey (2008) interviewed athletes who described their experiences with resiliency in sport. Key points included the following:

The most frequently cited stressors, along with the effectiveness of coping strategies, were investigated by Nicholls and colleagues (2005, 2008) using golfers and rugby players. Although many stressors and coping strategies were noted (some specific to the sport), the most frequently cited stressors were physical and mental errors, and the most effective coping strategies were focusing on the task, positive reappraisal, thought stopping, and increased effort. Finally, for coping with extreme physical duress such as “hitting the wall” in marathon running (Buman, Omli, Giacobbi, & Brewer, 2008), a variety of mental coping strategies were employed, including emotion-focused (e.g., social support) and cognitive strategies (e.g., willpower, mental reframing). A variety of coping strategies (both physical and mental) were necessary because it was difficult to know which one would be most effective in this arduous situation. In summary, there are great individual differences in coping strategies, and each athlete has to find what works best for him or her in specific situations.

Anecdotal Tips for Coping With Stress

In addition to the well-developed and carefully structured techniques we’ve discussed so far, other on-site procedures can help you cope with competitive stress. These techniques are not backed with scientific, empirical research but come from applied experience with athletes (Kirschenbaum, 1997; Weinberg, 1988, 2002). Choose the strategies that work best for your situation.

Coping With Emotions in Sport

Much of what has been discussed so far pertains to controlling and coping with excess anxiety and arousal. However, more recent research and application (Hanin, 2000; Jones, 2003; Lazarus, 2000) has broadened the study of anxiety to the study of emotions in sport such as happiness, enthusiasm, frustration, anger, determination, pessimism, fear, and fatigue. Coping with these emotions, some of which are seen as more positive (e.g., happiness) and some as more negative (e.g., anger), has been a recent concern of researchers. A number of different strategies to enhance emotional control (some of which are discussed in more detail in different chapters) have been put forth (Jones, 2003), including the following:

To generalize coping to other situations, Smith (1999) suggested that the following factors be considered:

Using Arousal-Inducing Techniques

So far we have focused on anxiety management techniques to reduce excess levels of anxiety. There are times, however, when you need to pump yourself up because you are feeling lethargic and underenergized. Perhaps you have taken an opponent too lightly and he has surprised you. Or you’re feeling tired in the fourth quarter. Or you’re feeling lackluster about your rehabilitation exercises. Unfortunately, various “psyching-up” strategies or energizing strategies have often been used by coaches inappropriately to pump athletes up for a competition. The key is to get athletes at an optimal level of arousal, and oftentimes things such as “pep talks” and motivational speeches can overarouse athletes. So if arousal is to be raised, it should be done in a deliberate fashion with awareness of optimal arousal states. Certain behaviors, feelings, and attitudes signal that you are underactivated:

You don’t have to experience all these signs to be underactivated. The more you notice, however, the more likely it is that you need to increase arousal. Although these feelings can appear at any time, they usually indicate you are not physically or mentally ready to play. Maybe you didn’t get enough rest, played too much (i.e., overtrained), or are playing against a significantly weaker opponent. The more quickly you can detect these feelings, the quicker you can start to get yourself back on track. Here we provide suggestions for generating more energy and activating your system. However, note that these are mostly individualized strategies (although some could be altered for teams) as opposed to team energizing strategies such as team goal setting, bulletin boards, media coverage or reports, and pep talks.

Thus far we have discussed individual strategies to become more energized, but at times a coach might have to energize an entire team. This might especially be the case if you are playing a much weaker team and believe that winning is “a lock.” Although several things can be done, two of the more typical are setting team or individual performance goals and giving a pep talk (goal setting is discussed in more detail in chapter 15). Setting goals in relation to your own team (not focusing solely on winning) can help keep energy high. For example, a heavily favored football team might set some team goals (e.g., to keep the opposition under 70 yards rushing, to average 5 yards per carry, and to have no quarterback “sacks”) to maintain intensity regardless of the score. Pep talks have been used extensively throughout the years, the most famous probably being Knute Rockne’s “Win one for the Gipper” speech at halftime of a Notre Dame football game. Many coaches have tried to emulate this pep talk, but contemporary thinking argues against such an approach. Specifically, such a talk suggests that all athletes need to be more energized, and this is most often not the case. However pep talks are still given, and some anecdotes from an applied perspective are provided next.

Pep Talks: An Applied Perspective

For a football coach (or any other team sport coach), giving a pregame or halftime speech is an art form as delicate as drawing up Xs and Os or structuring a game plan. Sometimes less is more and sometimes it’s not.

Knute Rockne probably invented the modern-day pep talk with his reference to All-American George Gipp, who had died several years earlier from an infection. Notre Dame was about to play heavily favored Army, and Rockne told his team, “The day before he died, George Gipp asked me to wait until the situation seemed hopeless, and then ask a Notre Dame team to go out and beat Army for him. This is the day and you are the team.” Notre Dame won 12-6 and thus “won one for the Gipper.”

Now “pep talks” take all different forms. For example, legendary coach Vince Lombardi came into the locker room at halftime with Green Bay losing to Detroit 21-3. The players were fearing an emotional outburst, but all Lombardi did was come in and say, “Men, we’re the Green Bay Packers.” Green Bay won 31-21. Urban Meyer, coach for the University of Florida, felt his team was flat going against Kentucky and had his assistant coaches throw things around the room to get the players excited and activated. Years ago, John Unitas, Hall of Fame quarterback for the Baltimore Colts, would have this to say to his team before starting a game: “Talk is cheap.” Then he’d just walk out of the locker room.

Finally, Lou Holtz, who has coached successfully at several major colleges, provides some guidelines for a successful pregame talk.

Learning Aids

Summary

1. Understand how to increase self-awareness of arousal states.

The first step toward controlling arousal levels is for athletes to become aware of the situations in competitive sport that cause them anxiety and of how they respond to these events. To do this, athletes can be asked to think back to their best and worst performances and then recall their feelings at these times. In addition, it is helpful to use a checklist to monitor feelings during practices and competitions.

2. Use somatic, cognitive, and multimodal anxiety reduction techniques.

A number of techniques have been developed to reduce anxiety in sport and exercise settings. The ones used most often to cope with somatic anxiety are progressive relaxation, breath control, and biofeedback. The most prevalent cognitive anxiety reduction techniques include the relaxation response and autogenic training. Two multimodal anxiety management packages that use a variety of techniques are (a) cognitive–affective stress management and (b) stress inoculation training. Finally, hypnosis has received more recent attention as an anxiety reduction technique as well as a method of improving other mental skills.

3. Identify coping strategies to deal with competitive stress.

The two major categories of coping are known as problem-focused coping and emotion-focused coping. Problem-focused coping strategies, such as goal setting or time management, involve efforts to alter or manage the problem that is causing stress. Emotion-focused coping involves regulating the emotional responses to the problem causing the stress. Having an array of coping strategies allows athletes to effectively cope with unforeseen events in a competition.

4. Describe on-site relaxation tips to reduce anxiety.

In addition to several well-developed and carefully structured techniques, on-site techniques have been identified to help sport and exercise participants cope with feelings of anxiety. These on-site tips usually involve having participants remember that they are out there to have fun and enjoy the experience.

5. Understand the matching hypothesis.

The matching hypothesis states that anxiety management techniques should be matched to the particular anxiety problem. That is, cognitive anxiety should be treated with mental relaxation, and somatic anxiety should be treated with physical relaxation.

6. Identify techniques to raise arousal for competition.

Sometimes energy levels need to be raised. Increased breathing, imagery, music, positive self-statements, and simply acting energized can all help increase arousal. The ability to regulate your arousal level is indeed a skill. To perfect that skill you need to systematically practice arousal regulation techniques, integrating them into your regular physical practice sessions whenever possible.

Key Terms

progressive relaxation

breath control

biofeedback

relaxation response

autogenic training

cognitive–affective stress management training (SMT)

stress inoculation training (SIT)

hypnosis

matching hypothesis

coping

problem-focused coping

emotion-focused coping

generalize

Review Questions

1. Discuss two ways to help athletes increase awareness of their psychological states.

2. Discuss the three basic tenets of progressive relaxation and give some general instructions for using this technique.

3. Describe the four elements of the relaxation response and how to use it.

4. Describe the approach taken, skills included, and phases involved in Meichenbaum’s stress inoculation training.

5. How does biofeedback work? Provide an example of its use in working with athletes.

6. Describe the theoretical model of stress underlying the development of the cognitive–affective stress management technique.

7. Discuss the four phases of cognitive–affective stress management, comparing and contrasting cognitive structuring and self-instructional training.

8. Define coping as suggested by Lazarus and Folkman. What are the advantages of defining coping in this way?

9. Describe and give contrasting examples of emotion-focused and problem-focused coping. Under what circumstances is each type of coping used in general?

10. Describe five different coping strategies that elite Olympic athletes used in the studies by Gould and colleagues.

11. Discuss three strategies for on-site reductions in anxiety and tension.

12. An athlete is having trouble getting psyched up for competition. How would you help this athlete get energized?

13. Discuss the current state of knowledge regarding the effects of hypnosis on athletic performance. Describe the steps (phases) of a hypnosis intervention.

14. Discuss two energizing strategies that you could use with an entire team. Why do you think these strategies would be effective?

15. Discuss three of the findings on coping obtained by Gould and his colleagues.

16. Describe three different strategies for coping with different emotions in sport.

17. If you wanted to generalize your coping skills from sport to other areas of life, what are at least three things you could do to maximize this transfer?

Critical Thinking Questions

1. You are getting ready to play the championship game to end your volleyball season in two weeks. You know that some of your players will be tense and anxious, especially because it’s the first time your team has reached the final game. But you have a few players who are always slow starters and seem lethargic at the beginning of competitions. What kinds of techniques and strategies would you use to get your players ready for this championship game?

2. Think back to a time when you were really anxious before a competition and when your anxiety had a negative effect on your performance. Now you know all about relaxation and stress management techniques as well as several specific coping strategies. If you had this same situation again, what would you do (and why) to prepare yourself to cope more effectively with your excess anxiety?