After reading this chapter, you should be able to

1. define concentration and explain how it is related to performance,

2. explain the main theories of concentration effects,

3. identify different types of attentional focus,

4. describe some attentional problems,

5. explain how self-talk works,

6. explain how to assess attentional ability, and

7. discuss how to improve attentional focus.

We hear the word focus more and more when athletes and coaches discuss getting ready to play and when they evaluate actual performance. Staying focused for an entire game or competition is often the key to victory (and losing that focus is the ticket to failure). Even in competitions lasting hours or days (such as golf), a brief loss of concentration can mar total performance and affect outcome. It is critical to concentrate during a competition, even through adverse crowd noise, weather conditions, and irrelevant thoughts. Top-level athletes are known to focus their attention and maintain that focus throughout a competition. This intense focus throughout an event is evident in the recollections of Olympic swimming gold medalist Michelle Smith: “I was never more focused in a race. No looking about, tunnel vision all the way … my concentration was so intense that I almost forgot to look up to see my time after touching the finishing pads” (cited in Roche, 1995, p. 1). A similar single-minded focus is seen in the following quote by gold medalist and world record holder in the 400 meters, Michael Johnson:

I have learned to cut all unnecessary thoughts on the track. I simply concentrate. I concentrate on the tangible—on the track, on the race, on the blocks, on the things I have to do. The crowd fades away and other athletes disappear and now it’s just me and this one lane.

On the other hand, we have all heard stories of athletes who have performed poorly because they lost concentration, such as the 100-meter sprinter who “missed” the gun; the basketball player distracted by the fans when shooting free throws; the tennis player whose thoughts fixated on a bad line call; and the baseball player mired in a slump, simply thinking that he would probably strike out again. In essence, the temporary loss of focus can spell defeat, as George Foreman commented after defeating Michael Moorer in the World Boxing Association championship: “They urged me to pile up some points, but I knew I could only win the fight by a knock-out. I waited and waited, until Moorer briefly lost his concentration and gave me an opening” (cited in Jones, 1994, p. 1). Or, as Shaquille O’Neal noted when he missed three dunks and went 0 for 5 from the foul line: “I wasn’t even concentrating, I was so upset. I simply lost my cool.”

Many athletes mistakenly believe that concentrating is important only during actual competition. All-time tennis great Rod Laver in effect says that the adage “practice makes perfect” is apt when it comes to developing concentration skills:

If your mind is going to wander during practice, it’s going to do the same thing in a match. When we were all growing up in Australia, we had to work as hard mentally as we did physically in practice. If you weren’t alert, you could get a ball hit off the side of your head. What I used to do was force myself to concentrate more as soon as I’d find myself getting tired, because that’s usually when your concentration starts to fail you. If I’d find myself getting tired in practice, I’d force myself to work much harder for an extra ten or fifteen minutes, and I always felt as though I got more out of those extra minutes than I did out of the entire practice. (Tarshis, 1977, p. 31)

In this chapter we explain how to effectively cope with the pressures of competition and to maintain concentration despite momentary setbacks, errors, and mistakes. We start by describing what concentration is and how it is related to performance. The terms concentration and attention are used interchangeably throughout the chapter, inasmuch as researchers tend to use the term attention and practitioners seem to prefer the term concentration.

Defining Concentration

Attention and its role in human performance have been subjects of debate and examination for more than a century, beginning with the following classic description by William James:

Everyone knows what attention is. It is taking possession by the mind, in clear and vivid form, of one out of what seems several simultaneously possible objects or trains of thought. Focalization, concentration of consciousness are the essence. It implies withdrawal from some things in order to deal effectively with others. (1890, pp. 403–404)

James’ definition focuses on one particular aspect of concentration (selective attention), although a more contemporary definition views attention more broadly as the concentration of mental effort on sensory or mental events (Solso, 1995). Moran (2004) stated that “concentration refers to a person’s ability to exert deliberate mental effort on what is most important in any given situation” (p. 103). You also hear popular metaphors for concentration such as “spotlight” or “zoom lens.” But a useful definition ofconcentration in sport and exercise settings typically contains four parts: (a) focusing on the relevant cues in the environment (selective attention), (b) maintaining that attentional focus over time, (c) having awareness of the situation and performance errors, and (d) shifting attentional focus when necessary.

Attentional Focus

A quarterback in football has to distinguish between what is relevant and what is irrelevant. When he stands behind the center and looks over the defense, he first must recognize the specific defensive formation to determine whether the play that was called will work. If he believes the linebackers are all going to blitz, he might decide to change the long pass he originally called to a quick pass over the middle. Of course, the linebackers are probably trying to fool the quarterback into thinking they are going to blitz when they really aren’t—a cat-and-mouse game occupying the quarterback’s attentional focus.

Now the quarterback has the ball and has dropped back to throw a pass. Seeing one of his teammates open, he is about ready to release the ball when, out of the corner of his eye, he notices a 250-pound lineman getting ready to slam into him. Is this lineman a relevant or an irrelevant cue for the quarterback? If the quarterback can release the ball before being tackled by the lineman, then the lineman is an irrelevant cue, even though the quarterback knows he will be hit hard right after he releases the ball. However, if the quarterback determines that the defensive lineman will tackle him before he can release the ball, then the lineman becomes a relevant cue that should signal the quarterback to “scramble out of the pocket” and gain more time to find an open receiver.

Focusing on Relevant Environmental Cues

Part of concentration refers to focusing on the relevant environmental cues, or selective attention. Irrelevant cues are either eliminated or disregarded. For example, a football quarterback with less than 2 minutes to play needs to pay attention to the clock, distance for a first down, and field position. But after the play is called, his focus needs to be on the defense, his receivers, and executing the play to the best of his ability. The crowd, noise, and other distracters should simply fade into the background. Or as Olympic champion in the 100-meter dash, Donovan Bailey, noted:

I was not thinking about the world record. When I go into a race thinking about times, I always screw up so I was thinking about my start and trying to relax. Just focus on doing the job at hand.

Similarly, learning and practice can help build selective attention—a performer does not have to attend to all aspects of the skill, because via extended practice, some of these become automated. For example, when learning to dribble, a basketball player typically needs all of her attention to be placed on the task, which means watching the ball constantly. However, when the player becomes more proficient, she can take her eyes off the ball (because this aspect of the skill has become automated and does not require consistent attentional focus); now she can be concerned with the other players on the court, who become relevant cues for the execution of a successful play.

A study by Bell and Hardy (2009) provides information regarding exactly what to focus on. Specifically, they found that an external focus (outside the body) was better than an internal focus (on the body). Moreover, a distal external focus produced better performance than a proximal external focus. For example, a golfer should focus more on the flight of the ball (distal external) than on the club face (proximal external) throughout the swing. Evidently, the more you focus on yourself or things near you (like the club in golf), the poorer the performance.

Maintaining Attentional Focus

Maintaining attentional focus for the duration of the competition is also part of concentration. This can be difficult, because thought-sampling studies have revealed that the median length of time during which thought content remains on target is approximately 5 seconds. So, on average, people engage in about 4,000 distinct thoughts in a 16-hour day. Thus, reigning in our thought process is not an easy task. This is seen as many athletes have instants of greatness, yet few can sustain a high level of play for an entire competition. Chris Evert was never the most physically talented player on the women’s tour, but nobody could match her ability to stay focused throughout a match. She was virtually unaffected by irrelevant cues such as bad line calls, missing easy shots, crowd noise, and her opponent’s antics. Concentration helped make her a champion.

Maintaining focus over long time periods is no easy task. Tournament golf, for example, is usually played over 72 holes. Say that after playing great for 70 holes, you have 2 holes left in the tournament and lead by a stroke. On the 17th hole, just as you prepare to hit your drive off the tee, an image of the championship trophy flashes in your mind. This momentary distraction causes you to lose your focus on the ball and hook your drive badly into the trees. It takes you three more strokes to get on the green, and you wind up with a double bogey. You lose your lead and wind up in second place. Thus, one lapse in concentration over the course of 72 holes costs you the championship. Tiger Woods has repeatedly noted that one of his great attributes is his ability to maintain his concentration throughout the 3 to 4 days of a golf tournament. In fact, Burke (1992) suggested different attentional styles depending on whether play is continuous (e.g., soccer), has a few breaks (e.g., basketball), or has many breaks (e.g., golf). The difficulty of maintaining concentration throughout a competition is the risk of losing concentration due to fatigue. In fact, tennis great and former number one player in the world, Bjorn Borg, has said that he was more mentally tired than physically tired after a match due to his total concentration on each and every point. The problem with having many breaks in the action such as golf is the risk of having trouble regaining concentration after the breaks. Ian Botham (former cricketer) switched his concentration on and off as necessary to keep his appropriate attentional focus:

I switch off the moment the ball is dead—then I relax completely and have a chat and joke…. But as soon as the bowler reaches his mark, I switch back on to the game. I think anybody who can concentrate totally all the time is inhuman. I certainly can’t.

Maintaining Situation Awareness

One of the least understood but most interesting and important aspects of attentional focus in sport is an athlete’s ability to understand what is going on around him. Known as situation awareness, this ability allows players to size up game situations, opponents, and competitions to make appropriate decisions based on the situation, often under acute pressure and time demands. For example, Boston Celtics announcer Johnny Most gave one of the most famous commentary lines in basketball when, in the seventh game of the 1965 NBA play-offs between the Boston Celtics and Philadelphia 76ers and with 5 seconds left, he screamed repeatedly, “and Havlicek stole the ball!” The Celtics’ John Havlicek later described how his situation awareness helped him make this critical play. The 76ers were down by a point and were taking the ball in from an out-of-bounds. Havlicek was guarding his man, with his back to the passer, when the referee handed the ball to the player in-bounding the ball. A team has 5 seconds to put the ball into play when throwing it in from out of bounds, and Havlicek started counting to himself 1001, 1002, 1003. When nothing had happened, he knew that the passer was in trouble. He turned halfway to see the passer out of the corner of his eye, still focusing on his own man. A second later he saw a poor pass being made and reacted quickly enough to deflect the ball to one of his own players, who ran out the clock. The Celtics won the game—and went on to win the NBA championship. Had Havlicek not counted, he would not have had a clear sense of the most important focus at that instant (Hemery, 1986).

Association or Dissociation: What Do We Know?

More than 25 years ago, studies of the cognitive strategies of marathon runners showed that the most successful marathoners tended to use an associative attentional strategy (monitoring bodily functions and feelings, such as heart rate, muscle tension, and breathing rate), whereas non-elite runners tended to use a dissociative attentional strategy (distraction and tuning out) during the race (Morgan & Pollock, 1977). Since then, many studies have been published in this area, including some that are more recent (e.g., Hutchinson & Tenenbaum, 2007; Stanley, Pargman, & Tenenbaum, 2007; Tenenbaum & Connolly, 2008). Recent research as well as a review of the past 20 years of research (Masters & Ogles, 1998) has found the following consistencies and yielded several recommendations regarding the use of associative and dissociative strategies in sport and exercise:

Association and dissociation should be seen more along a continuum than a dichotomy, especially when used in longer events (e.g., marathon running).

Association and dissociation should be seen more along a continuum than a dichotomy, especially when used in longer events (e.g., marathon running).

Use of associative strategies is generally correlated with faster running performance compared with use of dissociative strategies.

Use of associative strategies is generally correlated with faster running performance compared with use of dissociative strategies.

Runners in competition prefer association (focusing on monitoring bodily processes and forms as well as information management strategies related to race tactics), whereas runners in practice prefer dissociation, although both strategies are used in both situations. In essence, runners flip between these two strategies.

Runners in competition prefer association (focusing on monitoring bodily processes and forms as well as information management strategies related to race tactics), whereas runners in practice prefer dissociation, although both strategies are used in both situations. In essence, runners flip between these two strategies.

Dissociation is inversely related to physiological awareness and feelings of perceived exertion especially in laboratory studies, although not as consistently as in the field.

Dissociation is inversely related to physiological awareness and feelings of perceived exertion especially in laboratory studies, although not as consistently as in the field.

Dissociation does not increase the probability of injury, but it can decrease the fatigue and monotony of training or recreational runs.

Dissociation does not increase the probability of injury, but it can decrease the fatigue and monotony of training or recreational runs.

Association appears to allow runners to continue performing despite painful sensory input because they can prepare for and be aware of such physical discomfort.

Association appears to allow runners to continue performing despite painful sensory input because they can prepare for and be aware of such physical discomfort.

Dissociation should be used as a training technique for individuals who want to increase adherence to exercise regimens, because it makes the exercise bout more pleasant while not increasing the probability of injury or sacrificing safety.

Dissociation should be used as a training technique for individuals who want to increase adherence to exercise regimens, because it makes the exercise bout more pleasant while not increasing the probability of injury or sacrificing safety.

As workload increases, a shift from dissociation to association tends to focus needed mental attention to the task at hand.

As workload increases, a shift from dissociation to association tends to focus needed mental attention to the task at hand.

Along these lines, we all know of athletes who seem to be able to do just the right thing at the right time. Some who come to mind are LeBron James, Rafael Nadal, Misty May, and Teresa Edwards. Their awareness of the court and competitive situation always makes it seem as if they are a step ahead of everyone else. In fact, research has indicated that experts and nonexperts differ in their attentional processing (see “Expert–Novice Differences in Attentional Processing”).

Shifting Attentional Focus

Often it is necessary to shift attentional focus during an event, and this attentional flexibility is known as the ability to alter the scope and focus of attention as demanded by the situation. Let’s take a golf example. As a golfer prepares to step up to the ball before teeing off, she needs to assess the external environment: the direction of the wind, the length of the fairway, the positioning of water hazards, trees, and sand traps. This requires a broad–external focus. After appraising this information, she might recall previous experience with similar shots, note current playing conditions, and analyze the information she’s gathered to select a particular club and determine how to hit the ball. These considerations require a broad–internal focus.

Expert–Novice Differences in Attentional Processing

We all know that being able to size\ up a situation to know what to do—and possibly what your opponent is about to do—is a key attentional skill. Researchers (e.g., Abernethy, 2001) have studied how expert and novice performers differ in their attentional processes across a variety of sports even though there is no difference in eyesight (visual hardware) or perceptual–motor characteristics. Along these lines, a growing body of evidence suggests that “knowledge-based” factors, such as where an athlete directs her attention, can account for performance differences between expert and novice athletes in a variety of sports (Moran, 1996, 2004). Research has also revealed that the attentional skills of experts can be learned by novices (Abernethy, Wood, & Parks, 1999; Tenenbaum, Sar-El, & Bar-Eli, 2000), although there appear to be some innate differences. Some of the consistent differences that have emerged during the research process include the following:

Expert players attend more to advance information (e.g., arm and racket cues) than do novices and thus can make faster decisions and can better anticipate future actions.

Expert players attend more to advance information (e.g., arm and racket cues) than do novices and thus can make faster decisions and can better anticipate future actions.

Expert players attend more to movement patterns of their opponents than do novices.

Expert players attend more to movement patterns of their opponents than do novices.

Expert players search more systematically for cues than do novices.

Expert players search more systematically for cues than do novices.

Expert players selectively attend to the structure inherent in their particular sport more than novices (they can pick up structured offensive and defensive styles of play).

Expert players selectively attend to the structure inherent in their particular sport more than novices (they can pick up structured offensive and defensive styles of play).

Expert players are more successful in predicting the flight pattern of a ball than novices are.

Expert players are more successful in predicting the flight pattern of a ball than novices are.

Besides these attentional differences, recent research revealed that experts set more specific goals, selected more technique-oriented strategies to achieve these goals, made more strategy attributions, and displayed higher levels of self-efficacy than nonexperts (Cleary & Zimmerman, 2001). These attentional and psychological differences have important implications for the teaching and learning of motor skills. What might these be?

Once she has formulated a plan, she might monitor her tension, image a perfect shot, or take a deep, relaxing breath as part of a preshot routine. She has moved into a narrow–internal focus. Finally, shifting to a narrow–external focus, she addresses the ball. At this time, her focus is directly on the ball. This is not the time for other internal cues and thoughts, which would probably interfere with the execution of the shot. Golfers have ample time to shift attentional focus because they themselves set the pace. However, it is also important to be able to relax and lower the intensity of concentration at times between shots, because concentrating for extended periods of time is very energy consuming.

Shifting attention is also necessary, and often more difficult, when time pressures during a competition are intense. Hemery (1986) described how this might be the case during the running of a 400-meter hurdles race. The hurdler’s primary attention is narrow and external because of the need to focus and concentrate on the upcoming hurdle. However, the focus can change rapidly. For example, the hurdler uses a broad–internal focus to constantly review the stride lengths required to reach the next hurdle in the proper position for a rapid balanced clearance. He assesses the effects of the wind, track conditions, and pace on the stride pattern for clearing the next hurdle. He uses a broad–external focus to assess where he is in relation to all the other competitors in the race and a narrow–internal focus for personal race judgment and effort distribution. At any one instant, any one of these factors could be critical.

EXPLAINING ATTENTIONAL FOCUS: THREE PROCESSES

It is beyond the scope of this chapter to thoroughly discuss the various theories that have been proposed to help explain the attention–performance relationship. Thus, we provide a very brief description of the theories and refer interested readers to other work (Abernethy, 2001; Boutcher, 2008; Moran, 2003) for more complete reviews.

The major theories attempting to explain the role of attention in performance have used an information-processing approach. Early approaches favored either a single-channel approach (fixed capacity), where information is processed through a single channel, or a variable (flexible) approach, where individuals can choose where to focus their attention, allocating it to more than one task at a time. However, neither of these approaches proved fruitful, and current thinking now favors a multiple pools theory approach, which views attention like multiprocessors, with each processor having its own unique capabilities and resource–performer relationships. In essence, attentional capacity is seen not as centralized but rather as distributed throughout the nervous system. A possible application is that extensive practice could lead to the development of automaticity, where less actual processing time is needed because of overlearning of skills.

Within the information-process approach, three processes have received the most focus in trying to explain the attention–performance relationship.

Attentional Selectivity

Selective attention refers to letting some information into the information-processing system whereas other information is screened or ignored. Drawing on the work of Abernethy (2001), Perry (2005) proposed that a useful metaphor for understanding selective attention is a person who uses a “searchlight” to focus only on what is important. In fact, a recent review by Memmert (2009), found that it is not how long athletes focus, but rather, what they focus on that helps produce top performance. Three common errors are made when this searchlight is focused inappropriately:

Failure to focus all the attention on the essential or relevant elements of the task (searchlight beam is too broad)

Failure to focus all the attention on the essential or relevant elements of the task (searchlight beam is too broad)

Being distracted from relevant information by irrelevant information (searchlight is pointing in the wrong direction)

Being distracted from relevant information by irrelevant information (searchlight is pointing in the wrong direction)

Inability to divide attention among all the relevant cues that need to be processed concurrently (the searchlight’s beam is too narrow, or the person is unable to shift it rapidly enough from one spot to the next)

Inability to divide attention among all the relevant cues that need to be processed concurrently (the searchlight’s beam is too narrow, or the person is unable to shift it rapidly enough from one spot to the next)

As performers become more proficient in a given skill, they can move from more conscious control to more automatic (somewhat unconscious) control. In essence, when one is learning a skill, attention has to be targeted to all aspects of performing the skill itself (such as dribbling a basketball). But as one becomes more proficient, attention can be focused on watching other players (keeping one’s head up) because dribbling the ball has become more automatic. Most sport skills involve some conscious control, which can be cumbersome, and some automatic processing, which is more typical of skilled performance. Consistent practice can change a skill that requires lots of thinking to one that is automatic, which frees attention to be targeted to other aspects of the situation. The notion of selective attention is highlighted by Scotty Bowman’s comments (the U.S. Golf Association scorer) when referring to Tiger Woods at the U.S. Open in 2000 (which he won by an amazing 15 strokes):

His eye contact is right with his caddie and nowhere else when he’s preparing to hit a shot. He’s oblivious to everyone else. (Garrity, 2000, p. 61)

Attentional Capacity

This aspect of attention refers to the fact that attention is limited in the amount of information that can be processed at one time. But athletes seem to be able to pay attention to many things when performing. This is because they can change from controlled processing to automatic processing as they become more proficient. Controlled processing is mental processing that involves conscious attention and awareness of what you are doing when you perform a sport skill. For example when learning to hit a golf swing, athletes need to think about how to grip the club, address the ball, and perform the backswing and downswing. Automatic processing is mental processing without conscious attention. For example, as gymnasts become more proficient at performing their routine on the floor, they don’t need to attend to all the details of the jumps, dance moves, and sequences, as these should be virtually automatic after much practice. So as performers become more proficient and attentional capacity becomes more automatic, attention is freed up to focus on different aspects of the playing situation. That is why a skilled soccer player, for example, can focus on his teammates, opposition, playing style, and formations; he doesn’t have to pay much attention to dribbling the ball, because this is basically on automatic processing. The Boston Celtic basketball great Bill Russell referred to this limited channel capacity in a little different way:

Remember, each of us has a finite amount of energy, and things you do well don’t require as much. Things you don’t do well take more concentration. And if you’re fatigued by that, then the things you do best are going to be affected. (Deford, 1999, p. 110)

Attentional Alertness

Attentional alertness is related to the notion that increases in emotional arousal narrow the attentional field because of a systematic reduction in the range of cues that a performer considers in executing a skill. For example, numerous studies have indicated that in stressful situations, performance on a central visual task decreases the ability to respond to peripheral stimuli (Landers et al., 1985). Thus, it appears that arousal can bring about sensitivity loss to cues that are in the peripheral visual field. A point guard in basketball, for instance, can miss some important cues in the periphery (players on her team) if she is overaroused and as a result starts to narrow her attentional focus and field.

CONNECTING CONCENTRATION TO OPTIMAL PERFORMANCE

As noted at the outset of the chapter, athletes and coaches certainly recognize the importance of proper attentional focus in achieving high levels of performance. And research from several sources substantiates their experience. For example, researchers (Jackson & Csikszentmihalyi, 1999) investigated the components of exceptional performance and found eight physical and mental capacities that elite athletes associate with peak performance. Three of these eight are associated with high levels of concentration. Specifically, athletes describe themselves as (a) being absorbed in the present and having no thoughts about the past or future, (b) being mentally relaxed and having a high degree of concentration and control, and (c) being in a state of extraordinary awareness of both their own bodies and the external environment. In addition, in Orlick and Partington’s (1988) landmark study of Canadian Olympic athletes, concentration was a central component of performance that was repeatedly reinforced whether it was referring to quality training, mental preparation, distraction control, competition focus plans, or competition evaluation. For example, one athlete said this about quality training:

When I’m training I’m focused…. By focusing all the time on what you’re doing when you’re training, focusing in a race becomes a by-product. (p. 111)

Researchers comparing successful and less successful athletes have consistently found that attentional control is an important discriminating factor. In general, the studies reveal that successful athletes are less likely to become distracted by irrelevant stimuli; they maintain a more task-oriented attentional focus, as opposed to worrying or focusing on the outcome. Some researchers have argued that peak performers have developed exceptional concentration abilities appropriate to their sport. These observations led Gould and colleagues (1992c) to conclude that optimal performance states have a characteristic that is variously referred to as concentration, the ability to focus, a special state of involvement, or awareness of and absorption in the task at hand. This complete focus on the task is seen in Pete Sampras’ comment during his 1999 Wimbledon championship run when serving on match point (where he hit a second serve ace): “There was absolutely nothing going on in my mind at that time.”

To Watch or Not Watch the Ball: That Is the Question

Anyone who has played a sport involving a ball has probably often heard the admonishment, “Keep your eye on the ball.” Tennis players learn, “Watch the ball right onto the racket,” and baseball players, “Never take your eyes off the ball if you want to catch it.” However, researchers indicate that these long-held beliefs are not necessarily correct. For example, researchers have found that the eyes can be removed from the flight of the ball at some stage without causing a performance decrement (Savelsbergh, Whiting, & Pijpers, 1992). In addition, contrary to popular belief, top professional tennis players do not watch the ball approaching them as they prepare to return serve because it is virtually impossible for someone to track a ball traveling at speeds of 120 to 130 miles per hour (Abernethy, 1991). The same is true for baseball hitters trying to hit 90-mile-per-hour fastballs. Instead, these expert players use advance cues—such as the server’s racket and toss or the pitcher’s motion—to make informed judgments on where the ball will be going and what type of serve or pitch is coming toward them. This is not to say that watching the ball is unimportant. Rather, optimal performance is inevitably enhanced by an athlete’s ability to predict the flight of a ball from cues.

A related study (Castaneda & Gray, 2007) showed that batting performance of skilled baseball players was best when their attention was directed away from skill execution itself (internal) and focused on the effect of their body movements, which in this case was on the ball leaving the bat (external). In essence, the authors argue that the optimal focus for highly skilled batters is one that does not disrupt knowledge of skill execution (external focus) and permits attention to the perceptual effect of the action. Thus after picking up the cues from the pitcher’s motion, players should stay externally focused instead of refocusing on body mechanics and skill execution.

Eye movement patterns also confirm that expert players have a different focus of attention than have novice performers. Researchers have found this phenomenon in a variety of individual and team sports such as basketball, volleyball, tennis, soccer, baseball, and karate (for a review, see Moran, 1996). Think about the no-look passes that Magic Johnson was famous for making. Most good point guards in basketball, such as Dawn Staley and Chris Paul, now throw these kinds of passes. In reality, these point guards “see the floor” and anticipate where players will go (this skill gets better the more you play with teammates and become familiar with their movement patterns). Thus, these players accomplish the no-look pass by using advance cues to predict the future movement of their teammates.

IDENTIFYING TYPES OF ATTENTIONAL FOCUS

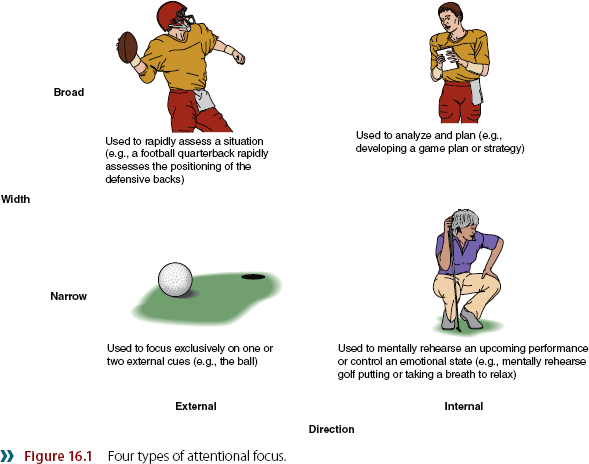

Most people think concentration is an all-or-none phenomenon—you either concentrate or you don’t. However, researchers have discovered that various types of attentional focus are appropriate for specific sports and activities. The most intuitively appealing work on the role of attentional style in sport (although we should note that this research has been questioned by some other researchers) has developed from the theoretical framework and practical work of Nideffer and colleagues (Nideffer, 1976a, 1976b, 1981; Nideffer & Segal, 2001), who view attentional focus along two dimensions: width (broad or narrow) and direction (external or internal).

Missing the “Open Player”: Attentional Errors in Team Sports

While watching a team sport such as soccer or basketball, one often cannot help wondering why the player with the ball did not pass to a much better positioned teammate, even though this player seemed to be right in her line of vision. When the coach or a teammate asks the player after the game why she did not pass the ball to the free player, the player typically responds that she hadn’t seen the other player. Although this sounds like an excuse, attentional research suggests another explanation for this phenomenon.

Specifically, Memmert and Furley (2007) found that giving players specific instructions can narrow their focus of attention and thus they can miss important cues (e.g., an open teammate). This is called inattentional blindness. In essence, team players often fail to find the optimal tactical solution to a situation because the coach narrows their attention by giving restrictive instructions. For example, if a coach has players watch for a specific situation or two and that situation does not occur, then players can have difficulty switching from the narrow focus conveyed by the coaches’ instructions to a broad focus, where the entire field can be surveyed. A wide or broad focus of attention facilitates noticing unmarked players in a dynamic situation like team sports. Of course, waving one’s hand can get the attention of the player but it also can get the attention of the defense, who can then alter their strategy and movement to guard the open player. Similarly, it was found that soccer players under pressure spend too much time focusing on the goalie, resulting in less accurate shots (Wilson, Wood, & Vine, 2009). This might be part of the reason there are more missed penalty kicks under high pressure situations in international soccer competitions.

A broad attentional focus allows a person to perceive several occurrences simultaneously. This is particularly important in sports in which athletes have to be aware of and sensitive to a rapidly changing environment (i.e., they must respond to multiple cues). Two examples are a basketball point guard leading a fast break and a soccer player dribbling the ball upfield.

A broad attentional focus allows a person to perceive several occurrences simultaneously. This is particularly important in sports in which athletes have to be aware of and sensitive to a rapidly changing environment (i.e., they must respond to multiple cues). Two examples are a basketball point guard leading a fast break and a soccer player dribbling the ball upfield.

A narrow attentional focus occurs when you respond to only one or two cues, as when a baseball batter prepares to swing at a pitch or a golfer lines up a putt.

A narrow attentional focus occurs when you respond to only one or two cues, as when a baseball batter prepares to swing at a pitch or a golfer lines up a putt.

An external attentional focus directs attention outward to an object, such as a ball in baseball or a puck in hockey, or to an opponent’s movements, such as in a doubles match in tennis.

An external attentional focus directs attention outward to an object, such as a ball in baseball or a puck in hockey, or to an opponent’s movements, such as in a doubles match in tennis.

An internal attentional focus is directed inward to thoughts and feelings, as when a coach analyzes plays without having to physically perform, a high jumper prepares to start her run-up, or a bowler readies his approach.

An internal attentional focus is directed inward to thoughts and feelings, as when a coach analyzes plays without having to physically perform, a high jumper prepares to start her run-up, or a bowler readies his approach.

Through combinations of width and direction of attentional focus, four different categories emerge, appropriate to various situations and sports (see figure 16.1).

Recognizing Attentional Problems

Many athletes recognize that they have problems concentrating for the duration of a competition. Usually, their concentration problems are caused by inappropriate attentional focus. As seen through interviews with elite athletes (Jackson, 1995), worries and irrelevant thoughts can cause individuals to withdraw their concentration “beam” from what they are doing to what they hope will not happen. They are not focusing on the proper cues; rather, they become distracted by thoughts, other events, and emotions. So they haven’t as much lost concentration as focused their concentration on inappropriate cues. We’ll now discuss some of the typical problems that athletes have in controlling and maintaining attentional focus, dividing these problems into distractions that are internal and those that are external.

Internal Distracters

Some distractions come from within ourselves—our thoughts, worries, and concerns. Jackson (1995) showed through interviews with elite athletes that worries and irrelevant thoughts can cause performers to lose concentration and develop an inappropriate focus of attention. Let us look at some of these internal distracters that present attentional problems.

Attending to Past Events

Some people cannot forget about what has just happened—especially a bad mistake. Focusing on past events has been the downfall of many talented athletes, because looking backward prevents them from focusing on the present. For example, archers who are preoccupied with past mistakes tend to produce poorer performances than those whose minds are focused on the present (Landers, Boutcher, & Wang, 1986). Interestingly, one of the mental challenges of individual sports is that they provide ample opportunity for rueful reflections about past mistakes and errors. But note how Lori Fung, the 1994 gold medalist in rhythmic gymnastics, positively deals with mistakes:

If you have a bad routine just go out and do the next one, and pretend the next one is the first routine of the day. You can’t do anything about it. You can’t do anything about the score you are getting; it’s over and done with. Sometimes it’s hard to make yourself forget it, but the more you try, the better you’re going to get at it in the future. (Orlick, 2000, p. 139)

Attending to Future Events

Concentration problems can also involve attending to future events. In essence, individuals engage in a form of “fortune-telling,” worrying or thinking about the outcome of the event rather than what they need to do now to be successful. Such thinking often takes the form of “what if” questions, such as “What if I lose the game?”; “What if I make another error?”; “What if I let my teammates down?”

Can You Identify the Proper Attentional Focus?

See if you can identify the proper attentional focus of a football quarterback under time duress. Fill in the term for the proper focus in the blank spaces here (the answers, which correspond to the numbers in the blanks, are given afterward).

As the quarterback calls the play, he needs a (1) ___________ focus to analyze the game situation, including the score, what yard line the ball is on, the down, and time left in the game. He also considers the scouting reports and the game plan that the coach wants him to execute in calling the play. As the quarterback comes up to the line of scrimmage, his focus of attention should be (2) ___________ while he looks over the entire defense and tries to determine if the originally called play will be effective. If he believes that another play might work better, he may change the play by calling an “audible” at the line of scrimmage. Next the quarterback’s attention shifts to a (3) ___________ focus to receive the ball from the center. Mistakes sometimes occur in the center–quarterback exchange because the quarterback is still thinking about the defense or what he has to do next (instead of making sure he receives the snap without fumbling). If a pass play is called, the quarterback drops back into the pocket to look downfield for his receivers. This requires a (4) ___________ perspective so the quarterback can evaluate the defense and find the open receiver while still avoiding onrushing linemen. Finally, after he spots a specific receiver, his focus becomes (5) ___________ as he concentrates on throwing a good pass.

Within a few seconds, the quarterback shifts attentional focus several times to effectively understand the defense and pick out the correct receiver. Examples of different types of attentional focus are shown in figure 16.1.

Answers

1. broad–internal; 2. broad–external; 3. narrow–external; 4. broad–external; 5. narrow–external

This kind of future-oriented thinking and worry negatively affects concentration, making mistakes and poor performance more likely. For example, Pete Sampras was leading 7-6, 6-4, and serving at 5-2 in the 1994 Australian Open finals. He double-faulted and lost two more games before holding out by 6-4 in the third set. Interviewed afterward, Sampras explained that his lapse in concentration was caused by speculating about the future. “I was thinking about winning the Australian Open and what a great achievement [it would be] looking ahead and just kind of taking it for granted, instead of taking it point by point.”

Sometimes future-oriented thinking has nothing at all to do with the situation. Your mind wanders without much excuse. For example, athletes report thinking during the heat of competition about such things as what they need to do at school the next day, what they have planned for that evening, or their girlfriend or boyfriend. These irrelevant thoughts are often involuntary—suddenly the players just find themselves thinking about things that have nothing to do with the present exercise or competi-

tion.

Choking Under Pressure

Emotional factors such as the pressure of competition often play a critical role in creating internal sources of distraction, and we often hear the word choking to describe an athlete’s poor performance under pressure. Tennis great John McEnroe underscores the point that choking is part of competition:

When it comes to choking, the bottom line is that everyone does it. The question isn’t whether you choke or not, but how—when you choke—you are going to handle it. Choking is a big part of every sport, and a part of being a champion is being able to cope with it better than everyone else.

—John McEnroe (cited in Goffi, 1984, pp. 61–62)

Although most players and coaches have their own ideas about what choking is, providing an objective definition is not easy. For example, read the three scenarios that follow and determine whether the athlete choked.

A basketball game is tightly fought, the lead shifting after each basket. Finally with 2 seconds left and her team down by two points, steady guard Julie Lancaster gets fouled in the act of shooting and is awarded two foul shots. Julie is a 90% free-throw shooter. She steps up to the line, makes her first shot but misses her second, and her team loses. Did Julie choke?

A basketball game is tightly fought, the lead shifting after each basket. Finally with 2 seconds left and her team down by two points, steady guard Julie Lancaster gets fouled in the act of shooting and is awarded two foul shots. Julie is a 90% free-throw shooter. She steps up to the line, makes her first shot but misses her second, and her team loses. Did Julie choke?

Jane is involved in a close tennis match. After splitting the first two sets with her opponent, she is now serving for the match at 5-4; the score is 30-30. On the next two points, Jane double-faults to lose the game and even the set at 5-5. However, Jane then comes back to break serve and hold her own serve to close out the set and match. Did Jane choke?

Jane is involved in a close tennis match. After splitting the first two sets with her opponent, she is now serving for the match at 5-4; the score is 30-30. On the next two points, Jane double-faults to lose the game and even the set at 5-5. However, Jane then comes back to break serve and hold her own serve to close out the set and match. Did Jane choke?

Bill is a baseball player with a batting average of .355. His team is in a one-game play-off to decide who will win the league championship and advance to the district finals. Bill goes 0 for 4 in the game, striking out twice with runners in scoring position. In addition, in the bottom of the ninth he comes up with the bases loaded and one out, and all he needs to do is hit the ball out of the infield to tie the game. Instead he grounds into a game-ending—and game-losing—double play. Did Bill choke?

Bill is a baseball player with a batting average of .355. His team is in a one-game play-off to decide who will win the league championship and advance to the district finals. Bill goes 0 for 4 in the game, striking out twice with runners in scoring position. In addition, in the bottom of the ninth he comes up with the bases loaded and one out, and all he needs to do is hit the ball out of the infield to tie the game. Instead he grounds into a game-ending—and game-losing—double play. Did Bill choke?

When people think of choking, they tend to focus on the bad performance at a critical time of the game or competition, such as a missed shot or dropped pass. However, choking is much more than the actual behavior—it is a process that leads to impaired performance. The fact that you missed a free throw to lose a game does not necessarily mean you choked. The more important questions to answer are why and how you missed the free throw.

Let’s take a closer look at the process that is characteristic of what we have come to call choking. Behaviorally, we infer that athletes are choking when their performance progressively deteriorates and they cannot regain control over performance. An example is the gymnast who allows an early mistake of falling off the balance beam to upset her and cause additional errors once she’s back on the beam. Choking usually occurs in a situation of emotional importance to the athlete. For example, Jana Novotna was serving at 4-1 in the third set of the 1993 Wimbledon finals against Steffi Graf and was one point away from a seemingly insurmountable 5-1 lead. But she proceeded to miss an easy volley, later served three consecutive double faults, and hit some wild shots, allowing Graf to come back to win 6-4. Many consider Wimbledon the most prestigious tournament to win, and thus the pressure for Novotna was extremely high.

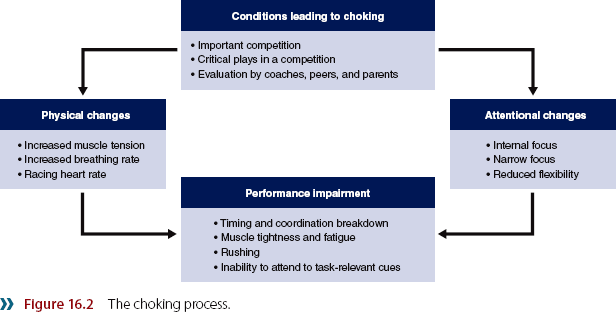

The choking process is shown in figure 16.2. Sensing pressure causes your muscles to tighten. Your heart rate and breathing increase; your mouth gets dry, and your palms get damp. But the key breakdown occurs at the attentional level: Instead of focusing externally on the relevant cues in your environment (e.g., the ball, the opponent’s movements), you focus on your own worries and fears of losing and failing, as your attention becomes narrow and internal. At the same time, the increased pressure reduces your flexibility to shift your attentional focus—you have problems changing your focus as the situation dictates. Impaired timing and coordination, fatigue, muscle tension, and poor decision making soon follow. An interesting recent study (Wilson, Vine, & Wood, 2009) found that increased anxiety affected basketball free-throw shooters by reducing the duration of the “quiet eye” period (the time of the final fixation on the target before the initiation of the movement). The “quiet eye” period is a time where task-relevant cues are processed and motor plans are developed. Thus, a longer duration minimizes distractions and allows focusing on relevant cues. In essence, the process of choking might, in part, result in shorter periods of focus on the task itself, leading to performance decrements.

A final look at choking analyzed situations in which athletes were more likely to choke. Specifically, Jordet and Hartman (2008) found that soccer players were more likely to choke (miss the shot) in a shootout (i.e., score tied) when a miss meant they would lose the game as opposed to a miss where the game would remain tied. In essence, when faced with needing a goal to keep a tie, players were more likely to miss than when faced with needing a goal to win the game. It appeared that players took more time (less automatic) before shots that might result in a loss, and this loss of automaticity was hypothesized to produce these performance differences.

Overanalyzing Body Mechanics

Another type of inappropriate attention is focusing too much on body mechanics and movements. When you’re learning a new skill, you should focus internally to get the kinesthetic feel of the movement. If you’re learning to ski downhill, for instance, you might focus on the transfer of weight, the positioning of your skis and poles, and simply avoiding a fall or running into other people. As you attempt to integrate this new movement pattern, your performance is likely to be uneven. That is what practice is all about—focusing on improving your technique by getting a better feel of the movement.

The problem arises when narrow–internal thinking continues after you have learned the skill. At this point the skill should be virtually automatic, and your attention should be primarily on what you’re doing with a minimum of thinking. If you are skiing in a competition for the fastest time, you should not be focusing on body mechanics. Rather, you should be externally focused on where you’re going, skiing basically on automatic pilot.

This doesn’t mean that no thinking occurs once a skill is well learned. But an emphasis on technique and body mechanics during competition is usually detrimental to performance because the mind gets in the way of the body. Or to use attentional terminology, a performer using conscious control processing (which is slow, requires effort, and is important in learning a skill) would have difficulty performing a skill in competition because he would be spending too much time focusing on what to do rather than using automatic processing (which requires little attention and effort).

Some interesting research (Beilock & Carr, 2001; Beilock, Carr, MacMahon, & Starkes, 2002) demonstrates the important role that attention plays in the choking process and the overanalysis of the movement itself. Specifically, attention on the task to be performed (attention to step-by-step execution) appears helpful to performers learning the skill, and thus teachers and coaches should draw learners’ attention to task-relevant, kinesthetic, and perceptual cues. However, skilled performers exhibited decreases in performance under conditions designed to prompt attention to step-by-step execution. Thus, what often happens when athletes choke is that they focus too much on the specifics of performing the task, and this added attention breaks down the movement pattern that has been automated and practiced over and over. In essence, what was once automatic is now being performed through conscious thought processes, but the skill is best performed without (or with minimum) conscious thought processes (Nieuwenhuys, Pijpers, Oudejans, & Bakker, 2008). Thus, added attention might be beneficial as performers learn a task, but it becomes counterproductive and detrimental in competition, when skills need to be performed quickly and automatically. Along these lines, Otten (2009) found that athletes who developed a greater sense of control and confidence (through practice) performed better in pressure situations than athletes who merely focus more attention on the task.

More recently, a study by Gucciardi and Dimmock (2008) highlights exactly what happens when someone “chokes.” The authors investigated two separate theoretical hypotheses for why athletes choke. The first is called the conscious processing hypothesis, which states that choking occurs when skilled performers focus too much of their conscious attention to the task, much as they would do if they were a novice at the task. In essence, they no longer perform on “automatic pilot”; rather, their conscious attention reverts back to the task when they are put in a pressure situation. The attention threshold hypothesis states that the increased pressure along with the attention needed to perform the task simply overloads the system and attentional capacity is exceeded. With not enough attentional capacity left in the system, performance deteriorates.

Results supported the conscious processing hypothesis as performance decreased only with increased focus on task-relevant cues. The authors argue that one global cue word (as opposed to focusing on several cues related to the task) would still focus the performer on the task (avoid irrelevant anxiety thoughts) while avoiding the increased attention seen when the focus is on several cues. For example, Curtis Granderson of the Detroit Tigers tends to think too much and gets analytical at the plate, which causes him problems. So he just tries to set an overall cue to focus on, which is “Don’t think, have fun.” For him, this means just going up and hitting while trusting his instincts. A thorough review of the relationship between anxiety and attention, exploring processing efficiency theory and attentional control theory, is provided by Wilson (2008).

Fatigue

Given our definition of attention, which involves mental effort, it is not surprising that concentration can be lost simply through fatigue. A high school football coach makes this point by saying, “When you get tired, your concentration goes. This results in impaired decision making, lack of focus and intensity, and other mental breakdowns. This is why conditioning and fitness are so important.” In essence, fatigue reduces the amount of processing resources available to the athlete to meet the demands of the situation.

Inadequate Motivation

If an individual is not motivated, it is difficult to maintain concentration, as the mind is likely to wander. As Jack Nicklaus (1974) stated:

Whenever I am up for golf—when either the tournament or course, or best of all both, excite and challenge me—I have little trouble concentrating…. But whenever the occasion doesn’t stimulate or challenge me, or I’m just simply jaded with golf, then is the time I have to bear down on myself with a vengeance and concentrate. (p. 95)

Irrelevant thoughts can occur simply because one is not focused, because a performer may believe it is not really necessary to focus when the competition is relatively weak. This “extra mental space” is quickly filled by thoughts of irrelevant cues.

External Distracters

External distracters may be defined as stimuli from the environment that divert people’s attention from the cues relevant to their performance. Unfortunately for performers, a variety of potential distractions exist.

Visual Distracters

One of the difficult aspects of remaining focused throughout an exercise bout or competition is that there are so many visual distracters in the environment that are competing for your attention. One successful diver described it this way:

I started to shift away from the scoreboard a year and a half before the Olympics because I knew that every time that I looked at the scoreboard my heart went crazy…. At the Olympics, I really focused on my dives rather than on other divers…. Before that I used to just watch the event and watch the Chinese and think “Oh, how can she do that? She’s a great diver.” I thought “I’m as good as anyone else, let’s stop thinking about them and focus on your own dives.” That was an important step in my career.

—Sylvie Bernier, 1984 Canadian Olympic diving champion (cited in Orlick, 2000, p. 91)

Spectators can cause a visual distraction and may affect some people’s concentration and subsequent performance by making them try too hard. We all want to look good when playing in front of people we know and care for, so we often start to press, tighten up, and try too hard. This usually results in poorer play instead of better, which embarrasses us and causes us to tighten up even more. In fact, in his research on “the championship choke,” Baumeister (1984) argued that increased self-consciousness elicited by home crowds can cause athletes to focus too much on the process of movement (i.e., control processing), causing a decrement in performance. Of course, some people actually play better in front of audiences they know. For many others, though, knowing people in the audience is a powerful distraction. Other visual distracters reported by athletes include the leader board in professional golf tournaments, the scoreboard that has scores of other games, and the television camera crews at courtside.

Auditory Distracters

Most sport competitions take place in environments where various types of noise may distract from one’s focus. Common auditory distracters include crowd noise, airplanes flying overhead (typically noted at the U.S. Open tennis championships in New York), announcements on the public address system, mobile telephones, beepers or other electronic paging devices, and loud conversations among spectators. Along these lines, an Olympic weightlifter competing in a major international competition missed out on a gold medal because a train rattled past the rear of the stadium as he prepared for his final lift. Similarly, earlier in her career, several top players complained that tennis great Monica Seles’ grunting hurt their concentration. As Seles tried to eliminate her grunting, she noted that the effort to do so impaired her own concentration, because she was now not hitting the ball automatically; rather she was thinking about not grunting! A good example of an external distracter comes from Olympic archer Grace Gaughan:

I was distracted by a low-flying helicopter that was taking people up to see a big mountain behind where we were shooting in Atlanta. For just a second, I lost concentration. It was a head to head competition with only 12 arrows so there was no margin for error—that was a short, sharp, swift end to my chances.

Accordingly, athletic success may hinge on an athlete’s ability to ignore such distracters while focusing on the most relevant cues to complete the task at hand. Noise and sounds are part of most team sports (e.g., basketball, soccer, hockey), although very quiet environments are expected for most individual sports (e.g., golf, tennis). Thus, a loud sound from the crowd is typically more disturbing to a golfer, who expects near silence, than to a hockey player, who probably expects the sound.

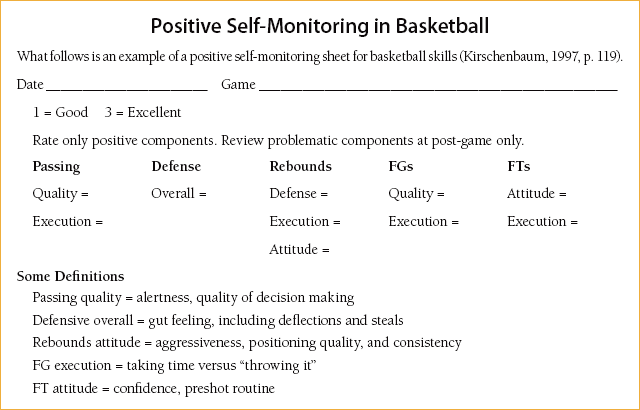

USING SELF-TALK TO ENHANCE CONCENTRATION

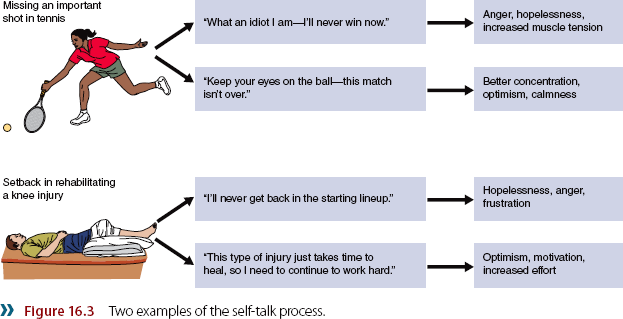

The previous section covered a variety of internal and external distractions typically present in the competitive environment. Self-talk is another potential internal distracter (although it can also be a way to deal with distractions). Anytime you think about something, you are in a sense talking to yourself. Self-talk has many potential uses (besides enhancing concentration), including breaking bad habits, initiating action, sustaining effort, and acquiring skill. The process of self-talk, in which self-talk functions as a mediator between an event and a response, is displayed in figure 16.3. As the relationship shows, self-talk plays a key role in reactions to situations, and these reactions affect future actions and feelings.

Self-talk can take many forms, but for convenience we will categorize it into three types: positive (motivational), instructional, and negative. Conroy and Metzler (2004) used a different model to characterize self-talk, although the specifics are beyond the scope of the present discussion. Positive self-talk typically focuses on increasing energy, effort, and positive attitude but does not carry any specific task-related cue (e.g., “I can do it” or “Just hang in there a little longer”). For example, gold medalist swimmer Nelson Diebel has used the word now to motivate him to kick extra hard at certain points in a race. Instructional self-talk usually helps the individual focus on the technical or task-related aspects of the performance in order to improve execution (e.g., “Keep your eyes on the ball” or “Bend your knees”). For instance, many volleyball spikers use the word extend to cue them to extend their arm when spiking a ball.

Negative self-talk is critical and self-demeaning and gets in the way of a person’s reaching goals; it is counterproductive and anxiety producing. Saying things like “That was a stupid shot,” “You stink,” or “How can you play so bad?” does not enhance performance or create positive emotions. Rather, it creates anxiety and fosters self-doubt. The performers who think positively about these negative events are usually the most successful. In fact, a recent study (Hardy, Roberts, & Hardy, 2009) found that athletes using a logbook to monitor self-talk became more aware of the content of their negative self-talk as well as the consequences of using negative self-talk. This could have important applied applications since, for most athletes, negative self-talk is detrimental to performance.

In a recent study (Zourbanos, Hatzigeorgiadis, Chroni, Thedorakis, & Papaioannou, 2009), a scale to assess self-talk was developed and the authors found eight different types (factors) of self-talk. This added some specificity to simply classifying self-talk as positive (motivational), instructional, or negative. The eight types were broken down into four positive categories including psych-up (power), confidence (I can make it), instruction (focus on your technique), and anxiety control (calm down); three negative categories including worry (I’m wrong again), disengagement (I can’t keep going), and somatic fatigue (I am tired); and one neutral category termed irrelevant thoughts (What will I do later tonight?). These additional categories highlight the varied nature of athletes’ and exercisers’ self-talk and can help coaches better understand what athletes are saying to themselves.

On a related topic, recent research conducted under the term ironic processes in sport has shown that trying not to perform a specific action can inadvertently trigger its occurrence (Janelle, 1999; Wegner, 1997; Wegner, Ansfield, & Piloff, 1998). In the laboratory, empirical evidence has recently been piling up demonstrating that what’s accessible in our minds can exert an influence on judgment and behavior simply because it is there. So, people trying to banish a thought from their minds—of a white bear, for example—find that the thought keeps returning about once a minute. Likewise, people trying not to think about a specific word continually blurt it out during rapid-fire word-association tests.

These same “ironic errors” are just as easy to evoke in the real world. So instructions such as “Whatever you do, don’t double-fault now,” “Don’t drive the ball into the bunker or lake,” and “Don’t choke” will typically produce the unwanted behavior. This is especially the case under pressure. For example, soccer players told to shoot a penalty kick anywhere but a certain spot of the net, like the lower right corner, look at that spot more often than any other. Similarly, golfers instructed to avoid a specific mistake, like overshooting, do it more often under pressure. In essence, to comply with these instructions to suppress a certain thought or image, we have to remember the instructions that include the forbidden thought—so we end up thinking it. A recent study (Woodman & Davis, 2008) demonstrated that “repressors” were particularly vulnerable to ironic processing errors. The reason is that repressors’ cognitive strategy is to inhibit the subjective distress related to anxiety, which simply increases their cognitive load, making them even more prone to ironic errors. In essence, by trying to reduce or get rid of their anxiety, they spend more time thinking about it, which just overloads the system and results in reduced performance. Therefore, we should focus on what to do instead of what not to do.

There are many uses of self-talk in addition to enhancing concentration, including increasing confidence, enhancing motivation, regulating arousal levels, improving mental preparation, breaking bad habits, acquiring new skills, and sustaining effort. These uses of self-talk are typically motivational or instructional, depending on the needs of the athlete. Interestingly, some recent research (Hanin & Stambulova, 2002) has shown that athletes make extensive use of metaphors in their self-talk (e.g., quick like a cheetah; strong like a bull) and that these metaphors, when generated by the performers themselves, are particularly helpful for changing behavior and performance.

Finally, other qualitative and quantitative research (Hardy, Gammage, & Hall, 2001; Hardy, Hall, & Hardy, 2004) has suggested that the content of self-talk can be divided into the following categories: (a) nature (positive or negative; internal or external); (b) structure (single cue words like breathe and concentrate vs. phrases like “Park it” and “Come on” vs. full sentences like “Don’t worry about mistakes that occur”); (c) person (one talks to oneself in the first person, using I and me, or in the second person, using you); and (d) task instruction (skill-specific phrases like “Tackle low” and “Keep your head up” vs. general instructions like “Get there faster” and “Stay tough throughout the race”). The researchers found two major functions of self-talk—cognitive (e.g., relating to skill development and skill execution) and motivational (e.g., relating to self-confidence, regulation of arousal, mental readiness, coping with difficult situations, and motivation). The use of self-talk varied based on the time of year, with self-talk being increasingly used as the year progressed from the off-season through the early competitive season to the late competitive season.

Self-Talk and Performance Enhancement

Although practitioners as well as researchers have argued the potentially important benefits of positive self-talk in enhancing task performance, only relatively recently has empirical research corroborated this assumption. In addition, although the focus here will be on performance enhancement, some recent research has shown self-talk to be effective in enhancing exercise adherence (Cousins & Gillis, 2005).

Regarding performance enhancement, Van Raalte, Brewer, Rivera, and Petitpas (1994) conducted an interesting descriptive analysis of audible self-talk and observable gestures that junior tennis players exhibited during competition. They found (a) that these junior tennis players displayed more negative than positive self-talk, (b) that negative self-talk was associated with poor performance on the court, and (c) that there was no significant association between audible, positive self-talk and performance. Thus, this sample of youth tennis players seemed to focus on the negative, and the self-talk they uttered undermined their performance.

Research using a variety of other athletic samples, however, has shown that different types of positive self-talk (i.e., instructional, motivational, mood related, self-affirmative) can enhance performance. These studies have been conducted, for example, with cross-country skiers (Rushall, Hall, & Rushall, 1988), beginning and skilled tennis players (Landin & Hebert, 1999; Ziegler, 1987), sprinters (Mallett & Hanrahan, 1997), soccer players (Johnson, Hyrcaiko, Johnson, & Halas, 2004), tennis players (Mamassis & Doganis, 2004), and figure skaters (Ming & Martin, 1996). The study with figure skaters is particularly impressive because self-report follow-ups a year after the intervention indicated that the participants continued to use the self-talk during practices and believed that it enhanced their competitive performance.

Furthermore, several investigations (Hatzigeorgiadis, Theodorakis, & Zourbanos, 2004; Hatzigeorgiadis, Zourbanos, Goltsios, & Theodorakis, 2008; Perkos, Theodorakis, & Chroni, 2002) have found both instructional and motivational self-talk effective for tasks varying in strength, accuracy, endurance, and fine motor coordination. This works by reducing the frequency of interfering thoughts while increasing the frequency of task-related thoughts. In addition, instructional self-talk can even help performance when knowledge of performance feedback is eliminated. In essence, even though subjects never received any feedback about their movement patterns, self-talk instructional cues were enough to produce performance increases during the learning of a skill (Cutton & Landin, 2007). Finally, recent research (Hamilton, Scott, & MacDougall, 2007) has revealed that both positive and negative self-talk may lead to enhanced performance. The authors hypothesize that the nature, content, and delivery of self-talk may not be as important as the individual interpretation of that self-talk. This underscores the importance of individual differences in relation to the effectiveness of different types of self-talk (Hatzigeorgiadis, Zourbanos, & Theodorakis, 2007).

A recent study underscores the notion that one needs to consider culture when looking at the effects of positive and negative self-talk on performance (Peters & Williams, 2006). Specifically, the authors compared the self-talk of European Americans and East Asians and found that East Asians had a significantly larger proportion of negative versus positive self-talk than European Americans. Although negative self-talk was related to poorer performance for the European Americans, it was related to better performance for the East Asians. It has been argued that there are fewer negative consequences of self-criticism for individuals from collectivist cultural backgrounds (e.g., East Asians) than for those from individualistic cultural backgrounds (e.g., European Americans). In any case, this has important implications for sport psychology consultants working with different populations and highlights the need to be sensitive to cultural differences.

Techniques for Improving Self-Talk

Mikes (1987) suggested six rules for creating self-talk for performance execution: (a) Keep your phrases short and specific; (b) use the first person and present tense; (c) construct positive phrases; (d) say your phrases with meaning and attention; (e) speak kindly to yourself; and (f) repeat phrases often. In addition to these suggestions, various techniques or strategies have been found to improve self-talk. Two of the most successful involve thought stopping and changing negative self-talk to positive self-talk.

Thought Stopping

One way to cope with negative thoughts is to stop them before they harm performance. Thought stopping involves concentrating on the undesired thought briefly and then using a cue or trigger to stop the thought and clear your mind. The trigger can be a simple word like stop or a trigger like snapping your fingers or hitting your hand against your thigh. What makes the most effective cue depends on the person.

Initially, it’s best to restrict thought stopping to practice situations. Whenever you start thinking a negative thought, just say “Stop” (or whatever cue you have chosen) aloud and then focus on a task-related cue. Once you have mastered this, try saying stop quietly to yourself. If there is a particular situation that produces negative self-talk (like falling during a figure skating jump), you might want to focus on that one performance aspect to stay more focused and aware of the particular problem. Old habits die hard, so you should practice thought stopping continuously.

Changing Negative Self-Talk to Positive Self-Talk

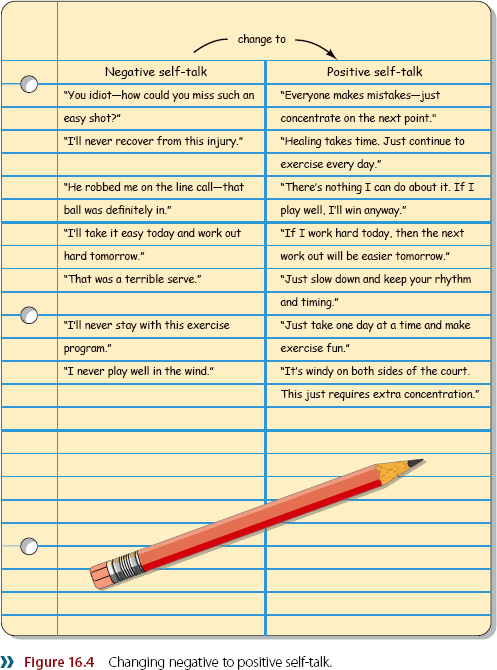

It would be nice to eliminate all negative self-talk, but in fact almost everyone has negative thoughts from time to time. When negative thoughts come, one way to cope with them is to change them into positive self-talk, which redirects attentional focus to provide encouragement and motivation. First, list all the types of self-talk that hurt your performance or that produce other undesirable behaviors. The goal here is to recognize what situations produce negative thoughts and why. Then try to substitute a positive statement for the negative one. When you’ve done this, create a chart with negative self-talk in one column and your corresponding positive self-talk in another (see figure 16.4).

To work on changing self-talk from negative to positive, use the same guidelines that you used for thought stopping. That is, do it in practice before trying it in competition. Because most negative thoughts occur under stress, first try to halt the negative thought and then take a deep breath. As you exhale, relax and repeat the positive statement. Let’s now look at some other skills connected with attention or concentration—specifically, how to assess attentional strengths and weaknesses.

ASSESSING ATTENTIONAL SKILLS

Before trying to improve concentration, you should be able to pinpoint problem areas, such as undeveloped attentional skills. Nideffer’s distinctions concerning attentional focus, that is, external versus internal and broad versus narrow, are useful in this regard. Nideffer argued that people have different attentional styles that contribute to differences in the quality of performance.

Test of Attentional and Interpersonal Style

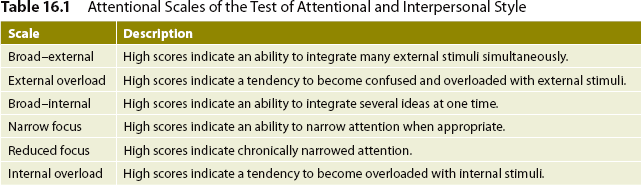

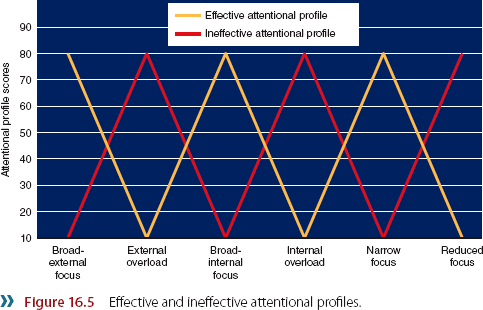

Nideffer (1976b) devised the Test of Attentional and Interpersonal Style (TAIS) to measure a person’s attentional style, or disposition. The TAIS has 17 subscales, 6 of them measuring attentional style (the others measure interpersonal style and cognitive control). Notice in table 16.1 that three of the scales indicate aspects of effective focusing (broad–external, broad–internal, and narrow focus), and three assess aspects of ineffective focusing (external overload, internal overload, and reduced focus).

Effective and Ineffective Attentional Styles

People who concentrate well (effective attenders) deal well with simultaneous stimuli from external and internal sources (see figure 16.5). They have high scores on broad–external and broad–internal focusing and can effectively switch their attention from a broad to a narrow focus as is necessary. Effective attenders are also low on the three measures of ineffective attention mentioned in the preceding paragraph, which means that they can attend to many stimuli without becoming overloaded with information. They also can narrow their attentional focus when necessary without omitting or missing any important information.

In contrast, people who don’t concentrate well (ineffective attenders) tend to become confused and overloaded by multiple stimuli, both internal and external. When they assume either a broad–internal or a broad–external focus, they have trouble narrowing their attentional width. For example, they may have trouble blocking out crowd noises or movement in the stands. Furthermore, the high score on the reduced-focus scale indicates that when they assume a narrow focus, it is so narrow that important information is left out. A soccer player, for example, might narrow his attentional focus to the ball and fail to see an opposing player alongside him who steals the ball! For ineffective attenders to perform better in sport competition, they must learn to switch their direction of attention at will and to narrow or broaden attention as the situation demands.

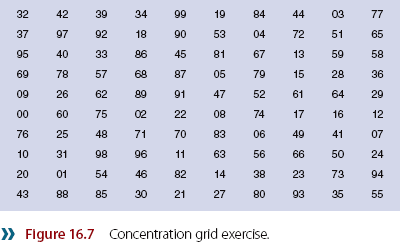

Test of Attentional and Interpersonal Style As a Trait Measure