After reading this chapter, you should be able to

1. discuss why people do or do not exercise,

2. explain the different models of exercise behavior,

3. describe the determinants of exercise adherence,

4. identify strategies for increasing exercise adherence, and

5. give guidelines for improving exercise adherence.

Lots of people appear to be exercising in an attempt to stay young and to improve the quality of their life. In addition, judging from the looks of store windows, we’re in the midst of a fitness craze. Most department stores carry a wide variety of athletic sportswear, not only for physical activity but also for leisure and even work. More and more fitness clubs appear to be opening up as people try to get or stay in shape. But the fact is that most Americans do not regularly participate in physical activity (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 1996, 1999).

Let’s look at some statistics to get a better idea of the level of exercise participation. These data are drawn from a variety of sources representing extensive surveys in many of the industrialized countries (e.g., Canadian Fitness and Lifestyle Research Institute, 1996; Caspersen, Merritt, & Stephens, 1994; Gauvin, Levesque, & Richard, 2001; Higgins, 2004; King et al., 2000; Sallis & Owen, 1999; USDHHS, 1999, 2000; Vainio & Biachini, 2002):

Physical activity rates within the United States are similar to those in other industrialized nations. Only 10% to 25% of American adults are active enough to maintain or increase cardiorespiratory and muscular fitness levels.

Physical activity rates within the United States are similar to those in other industrialized nations. Only 10% to 25% of American adults are active enough to maintain or increase cardiorespiratory and muscular fitness levels.

Among adults, 30% do not participate in any physical activity.

Among adults, 30% do not participate in any physical activity.

Among American adults in 2000, 19.8% (40 million) were considered obese compared with 12% in 1991.

Among American adults in 2000, 19.8% (40 million) were considered obese compared with 12% in 1991.

Among Americans, 66% were seen as overweight or obese in 2005. In fact from 2000 to 2005 obesity increased by 24% and the percentage of super obese increased by 75%.

Among Americans, 66% were seen as overweight or obese in 2005. In fact from 2000 to 2005 obesity increased by 24% and the percentage of super obese increased by 75%.

The propensity to be overweight increases with age, as 44% of people age 18 to 29 and 77% of people age 46 to 64 were overweight in 2005.

The propensity to be overweight increases with age, as 44% of people age 18 to 29 and 77% of people age 46 to 64 were overweight in 2005.

Among youths from 12 to 21 years of age, 50% do not participate regularly in physical acti-

Among youths from 12 to 21 years of age, 50% do not participate regularly in physical acti-

vity.

Among adults, only 10% to 15% participate in vigorous exercise regularly (three times a week for at least 20 minutes).

Among adults, only 10% to 15% participate in vigorous exercise regularly (three times a week for at least 20 minutes).

Of sedentary adults, only 10% are likely to begin a program of regular exercise within a year.

Of sedentary adults, only 10% are likely to begin a program of regular exercise within a year.

Among both boys and girls, physical activity declines steadily through adolescence from about 70% at age 12 to 30% to 40% by age 21.

Among both boys and girls, physical activity declines steadily through adolescence from about 70% at age 12 to 30% to 40% by age 21.

Among women, physical inactivity is more prevalent than among men, as it is among blacks and Hispanics compared with whites, older adults compared with younger ones, and the less affluent compared with the more affluent.

Among women, physical inactivity is more prevalent than among men, as it is among blacks and Hispanics compared with whites, older adults compared with younger ones, and the less affluent compared with the more affluent.

Of people who start an exercise program, 50% will drop out within 6 months.

Of people who start an exercise program, 50% will drop out within 6 months.

Most recently, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Data (2008) has provided information on physical activity patterns using revised definitions for minimum levels of physical activity. Some findings for 2008 include the following:

Approximately 72% of adults did not engage in a minimum of 20 minutes of vigorous physical activity for at least 3 days per week (little change from 2000).

Approximately 72% of adults did not engage in a minimum of 20 minutes of vigorous physical activity for at least 3 days per week (little change from 2000).

Approximately 50% of adults did not engage in a minimum of 20 minutes of vigorous physical activity for at least 3 days per week or moderate physical activity for at least 30 minutes at least 5 days per week.

Approximately 50% of adults did not engage in a minimum of 20 minutes of vigorous physical activity for at least 3 days per week or moderate physical activity for at least 30 minutes at least 5 days per week.

Approximately 47% of high school graduates and 15% of college graduates reported no leisure time physical activity.

Approximately 47% of high school graduates and 15% of college graduates reported no leisure time physical activity.

Approximately 25% of adults reported no leisure time physical activity—down from 30% throughout the 1990s.

Approximately 25% of adults reported no leisure time physical activity—down from 30% throughout the 1990s.

Approximately 19% of individuals ages 18 to 24 reported no leisure time physical activity compared to 27% of individuals ages 45 to 64 and 33% of individuals over 65 years of age.

Approximately 19% of individuals ages 18 to 24 reported no leisure time physical activity compared to 27% of individuals ages 45 to 64 and 33% of individuals over 65 years of age.

Approximately 26% of females and 22% of males reported no leisure time physical activity.

Approximately 26% of females and 22% of males reported no leisure time physical activity.

Blacks and Hispanics reported significantly more leisure time physical activity (33%) than did whites (22%).

Blacks and Hispanics reported significantly more leisure time physical activity (33%) than did whites (22%).

Thus, it is clear that as a society we are not exercising enough and this lack of physical activity is exacerbated by certain individual differences. This occurs despite the physiological and psychological benefits of exercise, including reduced tension and depression, increased self-esteem, lowered risk of cardiovascular disease, better weight control, and enhanced functioning of systems (metabolic, endocrine, and immune systems; see chapter 17). Only a relatively small percentage of children and adults participate in regular physical activity. This prompted a special issue of papers from the Academy of Kinesiology and Physical Education (Morgan & Dishman, 2001) targeted at exercise adherence. So let’s start by looking at why people exercise—as well as the reasons they give for not exercising.

REASONS TO EXERCISE

With much of the adult population either sedentary or not exercising enough to gain health benefits, the first problem that exercise leaders and other health and fitness professionals face is how to get these people to start exercising. People are motivated for different reasons (see chapter 3), but a good place to start is to emphasize the diverse benefits of exercise (President’s Council on Physical Fitness and Sport, 1996). Note that the issue of maintenance as well as initiation of physical activity is a critical one, because individuals must continue to be physically active to sustain the full health benefits of regular exercise (Marcus et al., 2000). So let’s look at some of the more typical reasons for people to start an exercise program.

Weight Control

Our society values fitness, good looks, and thinness, so staying in shape and keeping trim concern many people. However, an estimated 70 to 80 million American adults and 15 to 20 million American teenagers are overweight, and these numbers have been increasing over the past 10 years. In fact, recently there has been an increased focus on teenage obesity and obesity in general as a national epidemic. The first thing most people think to do when facing the fact that they are overweight is diet. Although dieting certainly helps people lose weight, exercise plays an important and often underrated role (and although dieting is never fun, exercise certainly can be fun). For example, some people assume that exercise does not burn enough calories to make a significant difference in weight loss, but this, too, is contrary to fact. Specifically, running 3 miles five times a week can produce a weight loss of 20 to 25 pounds in a year if caloric intake remains the same. Weight loss can have important health consequences beyond looking and feeling good. Obesity and physical inactivity are primary risk

factors for coronary heart disease. Thus, regular exercise not only improves weight control and appearance but also eliminates physical inactivity as a risk factor.

Exercising to lose weight can be seen as a self-presentational reason for exercising because this typically will result in enhancing physical appearance and improving muscularity (Hausenblas, Brewer, & Van Raalte, 2004). It is not surprising that some people are motivated to exercise for self-presentational reasons considering that positive self-presentation is strongly influenced by the aesthetic-ideal physique. Regardless of the current ideal physique (which has changed over time), people are influenced by it because of a self-presentational concern to look good and be popular.

Reduced Risk of Cardiovascular Disease

Research has produced evidence that regular physical activity (although we do not know the exact dose–response relationship) or cardiorespiratory fitness decreases the risk of mortality from cardiovascular disease in general and from coronary heart disease in particular. In fact, the decreased risk for coronary heart disease that is attributable to regular physical activity is similar in level to that for other lifestyle factors, such as refraining from cigarette smoking. In addition, regular exercise has been shown to prevent or delay the development of high blood pressure, and exercise reduces blood pressure in people with hypertension. Like obesity, hypertension is a prime risk factor in coronary heart disease, but research has indicated that it can be reduced through regular physical activity. So it is not surprising that a

summary of studies identified improvement in people’s physical and psychological health as the most salient behavioral advantage of exercise (Downs & Hausenblas, 2005).

Reduction in Stress and Depression

As discussed in chapter 17, regular exercise is associated with an improved sense of well-being and mental health. Our society has recently seen a tremendous increase in the number of people experiencing anxiety disorders and depression. Exercise is one way to cope more effectively with the society we live in and with our everyday lives.

Enjoyment

Although many people start exercise programs to improve their health and lose weight, it is rare for people to continue these programs unless they find the experience enjoyable. In general, people continue an exercise program because of the fun, happiness, and satisfaction it brings (Kimiecik, 2002; Titze, Stonegger, & Owen, 2005). Along these lines, Williams and colleagues (2006) found that individually tailored physical activity programs were more effective for individuals reporting greater enjoyment of physical activity at baseline. In essence, special attention needs to be paid to individuals who do not enjoy physical activity to start with, and exercise should be intrinsically motivating if a person is to adhere over a long period of time (this will be discussed in more detail later in the chapter).

Enhancement of Self-Esteem

Exercise is associated with increased feelings of self-esteem and self-confidence (Buckworth & Dishman, 2002), as many people get a sense of satisfaction from accomplishing something they couldn’t do before. Research (Whaley & Schrider, 2005) has revealed that hoped-for self of older adults (staying healthy and independent) was related to increases in exercise behavior. Something as simple as walking around the block or jogging a mile makes people feel good about moving toward their goals. In addition, people who exercise regularly feel more confident about the way they look.

Opportunities to Socialize

Often people start an exercise program for the chance to socialize and be with others. They can meet people, fight loneliness, and shed social isolation. Many people who lead busy lives find that the only time they have to spend with friends is when exercising together. In fact, almost 90% of exercise program participants prefer to exercise with a partner or group rather than alone. Exercising together gives people a sense of personal commitment to continue the activity and to derive social support from each other (Carron, Hausenblas, & Estabrooks, 1999).

REASONS FOR NOT EXERCISING

Despite the social, health, and personal benefits of exercising, many people still choose not to exercise, usually citing lack of time, lack of energy, and lack of motivation as their primary reasons for inactivity (Canadian Fitness and Lifestyle Research Institute, 1996). These are all factors that individuals have within their control, as opposed to environmental factors, which are often out of their control. (“Barriers to Physical Activity” shows that virtually all barriers to exercise are within the control of the individual.) This is consistent with research (McAuley, Poag, & Gleason, 1990) showing that the major reasons for attrition in an exercise program were internal and personally controllable causes (e.g., lack of motivation, time management), which are amenable to change.

A recent population-based study of over 2,200 individuals between the ages of 18 and 78 found important age and gender differences regarding reasons for not exercising (Netz, Zeev, Arnon, & Tenenbaum, 2008). For example, older adults (60-78) cited more health-related reasons (e.g., bad health, injury or disability, potential damage to health) for not exercising than their younger counterparts. In addition, older adults selected more internal barriers (e.g., I’m not the sporty type) than situational barriers (e.g., I haven’t got the energy) than younger adults. Furthermore, women, compared to men, selected more internal barriers (e.g., lack of self-discipline); since these are not easily amenable, this poses a difficult problem regarding adherence to exercise programs for these women. These findings underscore the notion that age and gender need to be considered in any discussion of reasons for not exercising.

For adolescents, some of the major barriers for participation in physical activity involve other factors such as lack of parents’ support, previous physical inactivity, siblings’ nonparticipation in physical activity, and being female (Sallis, Prochaska, & Taylor, 2000). In addition, in a recent analysis of 47 studies investigating exercise behavior that included special populations (Downs & Hausenblas, 2005), the main reasons for not exercising were (a) health issues (physical limitations, injury, poor health, pain or soreness, psychological problems); (b) inconvenience (lack of access to facilities, facility too crowded, lack of transportation, other commitments); (c) lacking motivation and energy (feeling lazy, feeling unmotivated, believing that exercise requires too much effort); (d) lacking social support (no exercise partner, no support from spouse); (e) insufficient time; and (f) lacking money (finding exercise programs too expensive). Some of the reasons most consistently given for not exercising are discussed next.

Perceived Lack of Time

The most frequent reason given for inactivity is a lack of time. In fact, 69% of truant exercisers cited lack of time as a major barrier to physical activity (Canadian Fitness and Lifestyle Research Institute, 1996). However, a closer look at schedules usually reveals that this so-called lack of time is more a perception than a reality. The problem lies in priorities—after all, people seem to find time to watch TV, hang out, or read the newspaper. When fitness professionals make programs enjoyable, satisfying, meaningful, and convenient, exercising can compete well against other leisure activities.

Lack of Energy

Many people keep such busy schedules that fatigue becomes an excuse for not exercising. In fact, 59% of nonexercisers said that lack of energy was a major barrier to physical activity. Fatigue is typically more mental than physical and often is stress related. Fitness professionals should emphasize that a brisk walk, bicycle ride, or tennis game can relieve tension and stress and be energizing as well. If these activities are structured to be fun, a person will look forward to them after a day that may be filled with hassles.

Lack of Motivation

Related to a lack of energy is a lack of sufficient motivation to sustain physical activity over a long period. It takes commitment and dedication to maintain regular physical activity when one’s life is busy with work, family, and friends. It is easy to let other aspects of life take up all your time and energy. So keeping in mind the positive benefits of physical activity becomes even more important to maintaining your motivation.

PROBLEM OF EXERCISE ADHERENCE

Once sedentary people have overcome inertia and started exercising, the next barrier they face has to do with continuing their exercising program. Evidently many people find it easier to start an exercise program than to stick with it: About 50% of participants drop out of exercise programs within the first 6 months. Figure 18.1 illustrates this steep dropoff in exercise participation during the first 6 months of an exercise program, which then essentially levels off until 18 months. Exercisers often have lapses in trying to adhere to exercise programs. A few reasons have been put forth as to why people have a problem with exercise adherence despite the fact that it is beneficial both physiologically and psychologically. These include the following:

The prescriptions are often based solely on fitness data, ignoring people’s psychological readiness to exercise.

The prescriptions are often based solely on fitness data, ignoring people’s psychological readiness to exercise.

Most exercise prescriptions are overly restrictive and are not optimal for enhancing motivation for regular exercise.

Most exercise prescriptions are overly restrictive and are not optimal for enhancing motivation for regular exercise.

Rigid exercise prescriptions based on principles of intensity, duration, and frequency are too challenging for many people, especially beginners.

Rigid exercise prescriptions based on principles of intensity, duration, and frequency are too challenging for many people, especially beginners.

Traditional exercise prescription does not promote self-responsibility or empower people to make long-term behavior change.

Traditional exercise prescription does not promote self-responsibility or empower people to make long-term behavior change.

However, Dishman and Buckworth (1997) noted that potential relapses may have a more limited impact if the individual plans and anticipates them, recognizes them as temporary impediments, and develops self-regulatory skills for preventing relapses to inactivity (see “Preventing a Relapse”). Finally, the importance of maintaining exercise over time (not relapsing) was shown in a recent study (Emery et al., 2003). Specifically, participants (individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) who adhered to an exercise program for a year experienced gains in cognitive functioning, functional capacity, and psychological well-being compared with those individuals who did not maintain an exercise program.

Given that exercise programs have a high relapse rate, they are like dieting, smoking cessation, or cutting down on drinking alcohol (Prochaska & Velicer, 1997). People intend to change a habit that negatively affects their health and well-being. In fact, fitness clubs traditionally have their highest new enrollments in January and February, when sedentary individuals feel charged by New Year’s resolutions to turn over a new leaf and get in shape. To accentuate the value of fitness, the marketing of exercise has accelerated in North America in a campaign of mass persuasion, with heavy advertising promoted by sportswear companies. So, why is it that some people who start an exercise program fail to stick with it, whereas others continue to make it part of their lifestyle?

THEORIES AND MODELS OF EXERCISE BEHAVIOR

One way to start answering this question is through the development of theoretical models that help us understand the process of exercise adoption and adherence (Culos-Reed, Gyurcsik, & Brawley, 2001). In this section we discuss some of the major models and theories.

Health Belief Model

The health belief model is one of the most enduring theoretical models associated with preventive health behaviors (Hayslip, Weigand, Weinberg, Richardson, & Jackson, 1996). Specifically, it stipulates that the likelihood of an individual’s engaging in preventive health behaviors (such as exercise) depends on the person’s perception of the severity of the potential illness as well as his appraisal of the costs and benefits of taking action (Becker & Maiman, 1975). An individual who believes that the potential illness is serious, that he is at risk, and that the pros of taking action outweigh the cons is likely to adopt the target health behavior. Although there has been some success in using the health belief model to predict exercise behavior, the results have been inconsistent because the model was originally developed to focus on disease, not exercise (Berger et al., 2002).

Preventing a Relapse

Unfortunately, when people start to exercise they often relapse into no exercise at all, or they exercise less frequently. Here are some tips to help prevent a relapse:

Expect and plan for lapses, such as scheduling alternative activities while on vacation.

Expect and plan for lapses, such as scheduling alternative activities while on vacation.

Develop coping strategies to deal with high-risk situations (e.g., relaxation training, time management, imagery).

Develop coping strategies to deal with high-risk situations (e.g., relaxation training, time management, imagery).

Replace “shoulds” with “wants” to provide more balance in your life. “Shoulds” put pressure and expectations on you.

Replace “shoulds” with “wants” to provide more balance in your life. “Shoulds” put pressure and expectations on you.

Use positive self-talk and imagery to avoid self-dialogues focusing on relapse.

Use positive self-talk and imagery to avoid self-dialogues focusing on relapse.

Identify situations that put you at risk and attempt to avoid or plan for these settings.

Identify situations that put you at risk and attempt to avoid or plan for these settings.

Do not view a temporary relapse as catastrophic because this undermines confidence and willpower (e.g., if you didn’t exercise for a week you are not a total failure; just start again next week).

Do not view a temporary relapse as catastrophic because this undermines confidence and willpower (e.g., if you didn’t exercise for a week you are not a total failure; just start again next week).

Theory of Planned Behavior

The theory of planned behavior (Ajzen & Madden, 1986) is an extension of the theory of reasoned action (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980). The theory of reasoned action states that intentions are the best predictors of actual behavior. Specifically, intentions are the product of an individual’s attitude toward a particular behavior and what is normative regarding the behavior (subjective norm). This subjective norm is the product of beliefs about others’ opinions and the individual’s motivation to comply with others’ opinions. For example, if you are a nonexerciser and believe that other significant people in your life (e.g., your spouse, children, friends) think you should exercise, then you may wish to do what these others want you to do.

Planned behavior theory extends the theory of reasoned action by arguing that intentions cannot be the sole predictors of behavior, especially in situations in which people might lack some control over the behavior. So in addition to the notions of subjective norms and attitudes, planned behavior theory states that perceived behavioral control—that is, people’s perceptions of their ability to perform the behavior—will also affect behavioral outcomes.

The theory of planned behavior has been useful in predicting exercise behavior, as seen in a study by Mummery and Wankel (1999). The authors found that swimmers who held positive attitudes toward training, believed that significant others wanted them to train hard (subjective norm), and held positive perceptions of their swimming ability (perceived behavioral control) formed stronger intentions to train and actually adhered to the training regimen significantly more than those who did not hold these attitudes and perceptions. Recently, behavioral intentions to increase exercise behavior have been distinguished from intentions to maintain exercise (Milne, Rodgers, Hall, & Wilson, 2008). Thus, when developing exercise interventions, the notion that exercise might unfold in phases (see transtheoretical model later in this chapter) needs to be considered. In addition, using the theory of planned behavior, e-mail messages (every other day for two weeks) were effective in increasing both intentions to exercise and actual exercise behavior compared to a control condition (Parrott, Tennant, Olejnik, & Poudevigne, 2008). Furthermore, the theory of planned behavior was extended, with self-identity and group norms added to the existing theory variables to help predict exercise behavior in adolescents (Hamilton & White, 2008). Finally, Dimmock and Banting (2009) argue that intentions, as the theory predicts, don’t necessarily influence behavior; rather the quality and strength of intentions are more important.

The importance of perceived behavioral control is also seen in a more recent study (Motl et al., 2005) that found behavioral control to be a good predictor of physical activity of more than 1,000 black and white female adolescents across a 1-year period. Along these lines, Martin and colleagues (2005) were able to predict moderate physical activity and cardiorespiratory fitness in African American children using the variables within the theory of planned behavior. Furthermore, research (Rhodes, Courneya, & Jones, 2004) indicates that personality traits should be included because they can mediate the predictions of planned behavior on exercise adherence. In addition, recent research has revealed that an individual may need to meet a certain threshold regarding perceived behavioral control and subjective norms in studies focused on predicting exercise behaviors and adherence (Rhodes & Courneya, 2005). Finally, the effectiveness of using the theory of planned behavior was demonstrated in predicting exercise intentions in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma survivors (Courneya, Vallance, Jones, & Reiman, 2005).

Social Cognitive Theory

Social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986, 1997, 2005) proposes that personal, behavioral, and environmental factors operate as reciprocally interacting determinants of each other. In essence, not only does the environment affect behaviors, but behaviors also affect the environment. Such personal factors as cognitions or thoughts, emotions, and physiology are also important. Despite this interaction among different factors, probably the most critical piece to this approach is an individual’s belief that he can successfully perform a behavior (self-efficacy). Self-efficacy has been shown to be a good predictor of behavior in a variety of health situations, such as smoking cessation, weight management, and recovery from heart attacks. In relation to exercise, self-efficacy theory has produced some of the most consistent findings, revealing an increase in exercise participation as self-efficacy increases (e.g., Maddison & Prapavessis, 2004; McAuley & Courneya, 1992), as well as increases in self-efficacy as exercise participation increases (McAuley & Blissmer, 2002). This important role of self-efficacy is especially the case where exercise is most challenging, such as in the initial stages of adoption or for persons with chronic diseases. For example, self-efficacy theory has predicted exercise behavior, which has been especially helpful for individuals with Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes as well as cardiovascular disease (Luszczynska & Tryburcy, 2008; Plotnikoff et al., 2008). In addition, when individuals relapse in their exercise behavior, the best predictor of whether they will resume exercise was recovery self-efficacy (Luszczynska et al., 2007). Finally, in a recent study (Martin & McCaughtry, 2008) investigating physical activity in inner-city African American children, results revealed that time spent outside and social support, as opposed to self-efficacy, were the best predictors of physical activity levels. This population has rarely been studied from a social cognitive perspective, and thus other factors besides self-efficacy may be the primary determinants of exercise behavior.

Self-Determination Theory

Self-determination theory was discussed in chapter 6 in relation to its influence on sport motivation and performance. Basically, the theory proposes that people are inherently motivated to feel connected to others within a social milieu (relatedness), to function effectively in that milieu (effectance), and to feel a sense of personal initiative in doing so (autonomy). Hagger and Chatzisarantis (2007, 2008) have summarized the recent research that has employed self-determination theory to predict exercise behavior. The studies generally indicate that participants who display autonomy in their exercise behavior (Standage, Sebire, & Loney, 2008) and have strong social support systems exhibit stronger motivation and enhanced exercise adherence. Self-determination theory was also able to predict adherence in overweight and obese participants (Edmunds, Ntoumanis, & Duda, 2007). However, since application of the theory to exercise is relatively new, additional intervention studies are needed to further test its predictions and utility in the exercise domain.

Evaluation Criteria for Theories of Health Behavior

A consensus exists that unhealthy behaviors are major causes of disease, premature death, and increased health care costs. Certainly lack of exercise has been related to many negative health outcomes (e.g., coronary heart disease, obesity). As a result, many theories (noted in this chapter) have been applied to exercise behavior. Recently, Prochaska, Wright, and Velicer (2008) provided guidelines to help evaluate the effectiveness of these different theories in predicting exercise behavior. In the following list, these are ordered from least to most important in terms of usefulness in practice and in value of enhancing health.

Clarity: The theory has well-defined terms that are operationalized and explicit.

Clarity: The theory has well-defined terms that are operationalized and explicit.

Consistency: The components do not contradict each other.

Consistency: The components do not contradict each other.

Parsimony: The theory explains the phenomenon in the least complex manner possible.

Parsimony: The theory explains the phenomenon in the least complex manner possible.

Testability: The propositions can be tested.

Testability: The propositions can be tested.

Empirical adequacy: The theory predicts when a behavior change will and will not occur.

Empirical adequacy: The theory predicts when a behavior change will and will not occur.

Productivity: It generates new questions and ideas and adds to the knowledge base.

Productivity: It generates new questions and ideas and adds to the knowledge base.

Generalizability: It generalizes to other situations, places, and times.

Generalizability: It generalizes to other situations, places, and times.

Integration: Constructs are combined in a meaningful and systematic pattern.

Integration: Constructs are combined in a meaningful and systematic pattern.

Utility: It provides health-related service and is usable.

Utility: It provides health-related service and is usable.

Practicality: A theory-based intervention produces greater behavior change than a placebo or a control.

Practicality: A theory-based intervention produces greater behavior change than a placebo or a control.

Impact: Impact = reach (the percentage of the target population participating) times number of behaviors changed times efficacy (amount of change).

Impact: Impact = reach (the percentage of the target population participating) times number of behaviors changed times efficacy (amount of change).

Transtheoretical Model

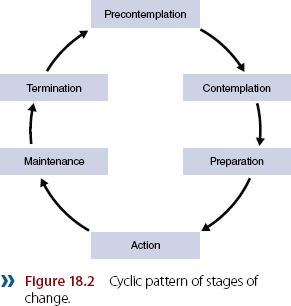

Although the models just discussed are useful as we try to grasp why people do or do not exercise, these constructs tend to focus on a given moment in time. However, the transtheoretical model (Prochaska, DiClemente, & Norcross, 1992) argues that individuals progress through stages of change and that movement across the stages is cyclic (see figure 18.2), rather than linear, because many people do not succeed in their efforts at establishing and maintaining lifestyle changes (Marcus, Buck, Pinto, & Clark, 1996). This model would argue that different interventions and information need to be tailored to match the particular stage an individual is in at the time (see “Matching the Exercise Intervention to the Individual”).

There are six stages in the transtheoretical model.

1.Precontemplation stage. In this stage, individuals do not intend to start exercising in the next 6 months. They are “couch potatoes.” People in this first stage may be demoralized about their ability to change, may be defensive because of social pressures, or may be uninformed about the long-term consequences of their behavior.

2.Contemplation stage. In this stage people seriously intend to exercise within the next 6 months. Despite their intentions, individuals usually remain in this second stage, according to research, for about 2 years. So the couch potato has a fleeting thought about starting to exercise but is unlikely to act on that thought.

3.Preparation stage. People in this stage are exercising some, perhaps less than three times a week, but not regularly. Hence, though our couch potato now exercises a bit, the activity is not regular enough to produce major benefits. In the preparation stage, individuals typically have a plan of action and have indeed taken action (in the past year or so) to make behavioral changes, such as exercising a little.

4.Action stage. Individuals in this stage exercise regularly (three or more times a week for 20 minutes or longer) but have been doing so for fewer than 6 months. This is the least stable stage; it tends to correspond with the highest risk for relapse. It is also the busiest stage, in which the most processes for change are being used. So our couch potato is now an active potato who could easily fall back into her old “couchly” ways.

5.Maintenance stage. Individuals in this stage have been exercising regularly for more than 6 months. Although they are likely to maintain regular exercise throughout the life span except for time-outs because of injury or other health-related problems, boredom and loss of focus can become a problem. In essence, sometimes the constant vigilance initially required to establish a new habit is tiring and difficult to maintain. Ideally the exerciser works to reinforce the gains made through the various stages to help prevent a relapse. Although most studies testing the transtheoretical model have focused on the earlier stages, Fallon, Hausenblas, and Nigg (2005) focused on the later stages (e.g., maintenance). Results revealed that increasing self-efficacy to overcome barriers to exercise was a critical factor for both males and females to continue exercising. In addition, people in the maintenance phase were found to be more intrinsically than extrinsically motivated (Buckworth et al., 2007).

6. Termination stage. Once an exerciser has stayed in this stage for 5 years, the individual is considered to have exited from the cycle of change, and relapse simply does not occur. At this stage, one is truly an active potato—and for a lifetime. In an interesting study, Cardinal (1997) found that approximately 16% of participants (more than 550) indicated that they were in the termination stage (criteria of 5 or more years of continuous involvement in physical activity and 100% self-efficacy in an ability to remain physically active for life). Cardinal concluded that individuals in the termination stage are resistant to relapse despite common barriers to exercise such as lack of time, no energy, low motivation, and bad weather.

In a large worksite promotion project (Marcus, Banspach, et al., 1992), participants were classified into the following categories: (a) 24% in precontemplation, (b) 33% in contemplation, (c) 10% in preparation, (d) 11% in action, and (e) 22% in maintenance. This approximate distribution pattern of the stages of change is found for other behaviors as well, such as smoking cessation and weight control. Researchers have found that when there is a mismatch between the stage of change and the intervention strategy, attrition is high. Therefore, matching treatment strategies to an individual’s stage of change is important to improve adherence and reduce attrition.

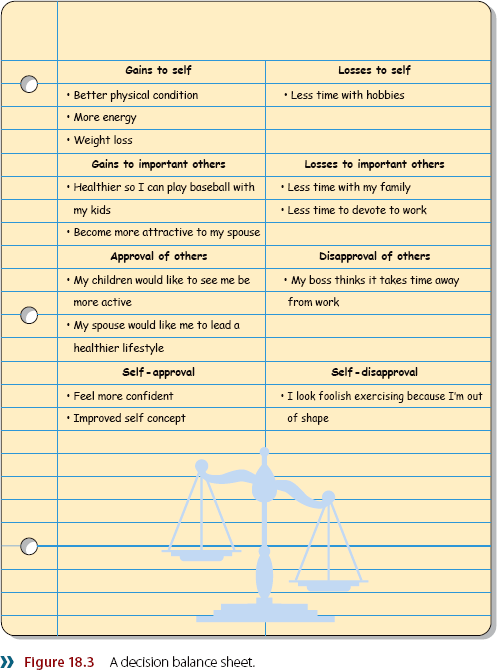

In making decisions about exercise, people go through a kind of cost–benefit analysis called decisional balance. Specifically, when people are considering a change in lifestyle, they weigh the pros and cons of a given behavior (e.g., Should I begin exercising?). In one study, researchers found that in the precontemplation and contemplation stages, the cons are usually greater than the pros. However, a crossover of the balance then occurs in the preparation stage, and the pros outweigh the cons in the action and maintenance stages (Prochaska et al., 1994). This is consistent with research (Landry & Solmon, 2004) using African American women, which found that motives for exercise become more internal as participants progressed through stages. Thus, approaches that focus on a sense of guilt or obligation, rather than fostering self-motivation, may actually have a negative effect on adherence. Therefore, exercise specialists need to help individuals who are contemplating exercise realize all of the benefits of exercise (i.e., become more intrinsically motivated) to help them move from contemplation to preparation. Finally, some contemporary research and thinking (Courneya, Friedenreich, Arthur, & Bobick, 1999) has begun to integrate different theories (in this case planned behavior and stages of change) to provide additional insights into why and how people successfully change their exercise behavior.

Physical Activity Maintenance Model

The models previously mentioned were not designed specifically for exercise adherence. To help better understand the long-term maintenance of physical activity, the physical activity maintenance model (PAM) was recently developed (Nigg, Borrelli, Maddock, & Dishman, 2008). The key aspects to the model predicting the maintenance of physical activity include

goal setting (commitment attainment, satisfaction),

goal setting (commitment attainment, satisfaction),

self-motivation (persistence in the pursuit of behavioral goals independent of any situational constraints),

self-motivation (persistence in the pursuit of behavioral goals independent of any situational constraints),

self-efficacy (confidence to overcome barriers and avoid relapse),

self-efficacy (confidence to overcome barriers and avoid relapse),

physical activity environment (e.g., access, aesthetics-attractiveness, enjoyable scenery, social support), and

physical activity environment (e.g., access, aesthetics-attractiveness, enjoyable scenery, social support), and

life stress (recent life changes, everyday hassles).

life stress (recent life changes, everyday hassles).

The authors feel that the development of a theoretical model can provide some coherence to the literature that has identified a host of correlates and predictors of physical activity initiation and maintenance.

Ecological Models

One class of models that has recently gained support in the study of exercise behavior is the ecological model. The term ecological refers to models, frameworks, or perspectives rather than a specific set of variables (Dishman et al., 2004). The primary focus of these models is to explain how environments and behaviors affect each other, bringing into consideration intrapersonal (e.g., biological), interpersonal (e.g., family), institutional (e.g., schools), and policy (e.g., laws at all levels) influences. Although all of these environments are important, it is argued (Sallis & Owen, 1999) that physical environments are really the hallmark of these ecological models. The most provocative claim is that ecological models can have a direct impact on exercise above that provided by social cognitive models. Although earlier physical environment variables can directly affect exercise behavior, future research is needed to determine if this occurs above and beyond the influence of social cognitive factors.

DETERMINANTS OF EXERCISE ADHERENCE

Theories help us understand the process of adopting, and later maintaining, exercise habits and give us a way to study this process. Another way researchers have attempted to study adherence to exercise programs is through investigating the specific determinants of exercise behavior. In a broad sense, the determinants fall into two categories: personal factors and environmental factors.

We’ll examine each category, highlighting the most consistent specific factors related to adherence and dropout rates. Table 18.2 summarizes the positive and negative influences on adherence, along with the variables that have no influence on exercise adherence (Dishman & Buckworth, 1998, 2001; Dishman & Sallis, 1994). However, it should be noted that the determinants of physical activity are not isolated variables; rather, they influence and are influenced by each other as they contribute to behavioral outcomes (King, Oman, Brassington, Bliwise, & Haskell, 1997). For example, someone who values physical fitness and is self-motivated may be less influenced by the weather and thus more likely to exercise when it is cold than someone for whom fitness is less important and who needs more external support and motivation.

Personal Factors

We can distinguish three types of personal characteristics that may influence exercise adherence: demographic variables, cognitive variables, and behaviors. We’ll discuss these in order.

Demographic Variables

Demographic variables traditionally have had a strong association with physical activity. For example, education, income, and socioeconomic status have all been consistently and positively related to physical activity. Specifically, people with higher incomes, more education, and higher occupational status are more likely to be physically active. For example, of individuals earning less than $15,000 annually, 65% are inactive compared with 48% of those earning more than $50,000. In addition, among people with less than a high school education, 72% are sedentary compared with 50% of college-educated individuals (U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1993). Conversely, people who smoke and are blue-collar workers are less likely to be as physically active as their nonsmoking and white-collar counterparts.

Regarding job status, many blue-collar workers may have the attitude that their job requires enough physical activity for health and fitness, but with the use of technology in today’s industry, most workers do not expend much energy compared with workers 50 years ago. In addition, interestingly, although males have a higher level of participation in physical activity than females, there are no differences in intensity of exercise.

Finally, some recent studies have used nonwhite participants, because groups who are nonwhite have been virtually absent from the literature and probably are at higher risk for low levels of physical activity (Eyler et al., 1998; Taylor, Baranowski, & Young, 1998). Along these lines, in one study (Kimm et al., 2002), black females decreased their physical activity by 100% from ages 10 to 19 whereas white girls decreased physical activity by 64%. However, results have shown that barriers to exercise were similar between white and nonwhite individuals, although the populations differed in other determinants of exercise (King et al., 2000). Obviously this is an area that needs more research. With the current epidemic of obesity, it is instructive to note that not only do obese people find it more difficult to exercise because weight bearing is difficult, but they tend to relapse after dieting and typically regain any weight loss within 3 to 5 years.

Cognitive and Personality Variables

Many cognitive variables have been tested over the years to determine if they help predict patterns of physical activity. Of all the variables tested, self-efficacy

and self-motivation have been found to be the most consistent predictors of physical activity. Self-efficacy is simply an individual’s belief that he can successfully perform a desired behavior. Getting started in an exercise program, for example, is likely affected by the confidence one has in being able to perform the desired behavior (e.g., walking, running, aerobic dance) and keep the behavior up. Therefore, exercise specialists need to help people feel confident about their bodies through social support, encouragement, and tailoring of activities to meet their needs and abilities. Specialists also should provide beginning exercisers with a sense of success and competence in their exercise programs to enhance their desire to continue participation.

Self-motivation has also been consistently related to exercise adherence and has been found to distinguish adherents from dropouts across many settings, including adult fitness centers, preventive medicine clinics, cardiac rehabilitation units, and corporate fitness gyms (Dishman & Sallis, 1994). Evidence suggests that self-motivation may reflect self-regulatory skills, such as effective goal setting, self-monitoring of progress, and self-reinforcement, which are believed to be important in maintaining physical activity. Combined with other measures, self-motivation can predict adherence even more accurately. For example, when self-motivation scores were combined with percent body fat, about 80% of subjects were correctly predicted to be either adherents or dropouts (Dishman, 1981).

The cumulative body of evidence also supports the conclusion that beliefs about and expectations of benefits from exercise are associated with increased physical activity levels and adherence to structured physical activity programs among adults (e.g., Marcus, Pinto, Simkin, Audrain, & Taylor, 1994; Marcus et al., 2000). In fact, population-based educational campaigns can modify knowledge, attitudes, values, and beliefs regarding physical activity; these changes then can influence individuals’ intentions to be active and finally their actual level of activity. Therefore, specialists need to inform people of the benefits of regular physical activity and give them ways to overcome perceived barriers. A way to provide this type of information (see Marcus, Rossi, et al., 1992), for example, is to distribute exercise-specific manuals to participants, based on their current stage of physical activity.

Behaviors

Among studies of the many behaviors that might predict physical activity patterns in adulthood, research on a person’s previous physical activity and sport participation has produced some of the most interesting findings. In supervised programs in which activity can be directly observed, past participation in an exercise program is the most reliable predictor of current participation (Dishman & Sallis, 1994). That is, someone who has remained active in an organized program for 6 months is likely to be active a year or two later.

There is little evidence that mere participation in school sports, as opposed to a formal exercise program, in and of itself will predict adult physical activity. Similarly, there is little support for the notion that activity patterns in childhood or early adulthood are predictive of later physical activity. Evidently, the key element is that an individual has developed a fairly recent habit of being physically active during the adult years regardless of the particular physical activity pattern. However, active children who receive parental encouragement for physical activity will be more active as adults than will children who are sedentary and do not receive parental support. Along these lines, an extensive survey of some 40,000 schoolchildren in 10 European countries revealed that children whose parents, best friends, and siblings took part in sport and physical activity were much more likely themselves to take part and continue to exercise into adulthood (Wold & Anderssen, 1992). In addition, just the most active 10% of children did not have declines in physical activity from ages 12 to 18. These results underscore the importance of adults’ encouraging youngsters and getting them involved in regular physical activity and sport participation early in life, as well as serving as positive role models.

Environmental Factors

Environmental factors can help or hinder regular participation in physical activity. These factors include the social environment (e.g., family and peers), the physical environment (e.g., weather, time pressures, and distance from facilities), and characteristics of the physical activity (e.g., intensity and duration of the exercise bout). Environments (i.e., communities) that promote increased activity—offering easily accessible facilities and removing real and perceived barriers to an exercise routine—are probably necessary for the successful maintenance of changes in exercise behavior. For example, adherence to physical activity is higher when individuals live or work closer to a fitness club, receive support from their spouse for the activity, and can manage their time effectively. Although most of the determinants studied in the past have been demographic, personal, behavioral, psychological, and programmatic factors, more attention has been given recently to environmental variables (Sallis & Owen, 1999).

Social Environment

Social support is a key aspect of one’s social environment, and such support from family and friends has consistently been linked to physical activity and adherence to structured exercise programs among adults (USDHHS, 1996). A spouse has great influence on exercise adherence, and a spouse’s attitude can exert even more influence than one’s own attitude (Dishman, 1994). In the Ontario Exercise-Heart Collaborative Study (Oldridge & Jones, 1983), the dropout rate among patients whose spouses were indifferent or negative toward the program was three times greater than among patients whose spouses were supportive and more enthusiastic. Similarly, Raglin (2001a) found a dropout rate for married-singles (only one person from a married couple exercising) of 43%, whereas for married-pairs (both people in the exercise program) the dropout rate was only 6.3%. Thus, actually taking part in an exercise program provides a great deal of support for a spouse. Social support was also found to be effective in injury rehabilitation settings (Levy, Remco, Polman, Nicholls, & Marchant, 2009). Specifically, athletes felt that social support helped them cope with the stress of being injured and not being able to participate in their sport. Friends, family, and the physiotherapist were seen as offering different types of social support (e.g., task support, emotional support). Finally, a review by Carron, Hausenblas, and Mack (1996) found that for social variables, influence of support by family and important others on attitudes about exercise was the strongest predictor of adherence.

Exercise professionals can use a participant’s family or spousal support to arrange an orientation session for family members, such as educating spouses on all aspects of the exercise program to foster their understanding of the goals. In Erling and Oldridge’s (1985) cardiac rehabilitation study, the dropout rate, which had been 56% before initiation of a spouse program, decreased to only 10% for patients with a spouse in the support program. Encouragement for a friend, family member, or peer who is trying to get back to or stay in an exercise program can be as simple as saying, “Way to go” or “I’m proud of you.”

Physical Environment

A convenient location is important for regular participation in community-based exercise programs. Both the perceived convenience and the actual proximity to home or worksite are factors that consistently affect whether someone chooses to exercise and adheres to a supervised exercise program (King, Blair, & Bild, 1992). The closer to a person’s home or work the exercise setting is, the greater the likelihood that the individual will begin and stay with a program. Such locations as schools and recreation centers offer potentially effective venues for community-based physical activity programs (Smith & Biddle, 1995). Along these lines, King and colleagues (2000) found that approximately two-thirds of the women in their study expressed a preference for undertaking physical activity on their own in their neighborhood rather than going to a fitness facility. In addition, Sallis (2000) argued that one of the major reasons for the current epidemic of inactive lifestyles is the modern built environment, whose design includes formidable barriers to physical activity such as a lack of biking and walking trails, parks, and other open places where physical activity could occur.

Besides the actual location of the physical activity is the climate or season, with activity levels lowest in winter and highest in summer. In addition, from observational studies, the time spent outdoors is one of the best correlates of physical activity in preschool children (Kohl & Hobbs, 1998).

Still, the most prevalent and principal reason people give for dropping out of supervised clinical and community exercise programs is a perceived lack of time (Dishman & Buckworth, 1997). When time seems short, people typically drop exercise. How many times have you heard someone say, “I’d like to exercise but I just don’t have the time”? For many people, however, this perceived lack of time reflects a more basic lack of interest or commitment. Regular exercisers are at least as likely as sedentary people to view time as a barrier to exercise. For example, women who work outside the home are more likely than those who do not to exercise regularly, and single parents are more physically active than parents in two-parent families. So it is not clear that time constraints truly predict or determine exercise participation. Rather, physical inactivity may have to do more with poor time management skills than with too little time. Therefore, helping new exercisers deal more effectively with the decision of when to exercise might be especially beneficial.

Although lack of time has been cited as a major reason for physical inactivity, home exercise equipment has not solved the inactivity problem. For example, Americans spent nearly three times as much on home exercise equipment in 1996 as in 1986 (1.2–3 billion). However, during that period, moderate to vigorous physical activity increased only 2%, and a lot of that equipment ended up in people’s garages and closets.

Physical Activity Characteristics

The success or failure of exercise programs can depend on several structural factors. Some of the more important factors are the intensity, frequency, and duration of the exercise; whether the exercise is done in a group or alone; and qualities of the exercise leader.

Exercise Intensity, Frequency, and Duration Discomfort during exercise can certainly affect adherence to a program. High-intensity exercise is more stressful on the system than low-intensity exercise, especially for people who have been sedentary. People in walking programs, for example, continue their regimens longer than do people in running programs. One study showed that dropout rates (25%–35%) with a moderate-level activity are only about half what is seen (50%) for vigorous exercise (Sallis et al., 1986). Furthermore, research indicated that adherence rates in exercise programs were best when individuals were exercising at 50% of their aerobic capacity or less (Dishman & Buckworth, 1997; USDHHS, 1996). Williams (2007, 2008) provides evidence that individuals (especially those who were inactive, obese, or both) who chose self-paced intensities that produced positive affect exhibited higher levels of adherence. This is contrary to many recommendations that individuals should exercise at a certain intensity level. Williams concludes that allowing participants to select intensity levels related to pleasant feelings while avoiding exercise that elicits unpleasant feelings can be particularly helpful in terms of adherence for obese and sedentary individu als, who often exhibit discomfort when exercising (and subsequently drop out).

Finally, most recently, research has revealed that the level of past activity may moderate the effects of exercise intensity on adherence (Anton et al., 2005). Specifically, it was found that participants with higher levels of past physical activity exhibited better adherence to higher-intensity exercise but tended to have poorer adherence to moderate-intensity exercise. Thus, an individual’s prior exercise experience should be considered when prescribing an exercise regimen.

Different recommendations regarding the frequency and duration of exercise have been made by different scholarly organizations. For example, the American College of Sports Medicine and the Centers for Disease Control recommend that people accumulate 30 minutes or more of moderate-intensity physical activity most days of the week to encourage sedentary people (who usually do very little physical activity) to perform activities such as gardening, walking, and household chores in short dosages (e.g., 5-10 minutes). Other groups such as the Food and Nutrition Board of the Institute of Medicine recommend at least 1 hour per day of moderate-intensity physical activity (Couzin, 2002). However, research has revealed that multiple short bouts of exercise led to similar long-term increases in physical activity and weight loss compared with traditional longer sessions of 30 minutes or longer (Jakicic, Winters, Lang, & Wing, 1999). Thus, the key point is that people need to get regular physical activity, and there appears no best way to accomplish this goal.

More vigorous physical activity carries a greater risk for injury. In fact, injury is the most common reason given for the most recent relapse from exercise, and participants who report temporary injuries are less likely than healthy individuals to report vigorous exercise (Dishman & Buckworth, 1997). In starting an exercise program, many people try to do too much the first couple of times out and wind up with sore muscles, injuries to soft tissues, or orthopedic problems. Of course, they find such injury just the excuse they need to quit exercising. The message to give them is that it is much better to do some moderate exercise than try to shape up in a few weeks by doing too much, too soon.

Comparing Group With Individual Programs Group exercising leads to better adherence than exercising alone does (Dishman & Buckworth, 1996). Group programs offer enjoyment, social support, an increased sense of personal commitment to continue, and an opportunity to compare progress and fitness levels with others. One reason people exercise is for affiliation. Being part of a group fulfills this need and also provides other psychological and physiological benefits. There tends to be a greater commitment to exercise when others are counting on you. For example, if you and a friend agree to meet at 7 AM four times a week to run for 30 minutes, you are likely to keep each appointment so that you don’t disappoint your friend. Although group programs are more effective in general than individual programs, certain people prefer to exercise alone for convenience. In fact, about 25% of regular exercisers almost always exercise alone. Therefore, it is important for exercise leaders to understand the desires of participants to exercise in a group or alone.

Leader Qualities Although little empirical research has been conducted in the area, anecdotal reports suggest that program leadership is important in determining the success of an exercise program. A good leader can compensate to some extent for other program deficiencies, such as a lack of space or equipment. By the same token, weak leadership can result in a breakdown in the program, regardless of how elaborate the facility is. This underscores the importance of evaluating not only a program’s activities and facilities but also the expertise and personality of the program leaders. Good leaders are knowledgeable, are likeable, and show concern for safety and psychological comfort. Bray, Millen, Eidsness, and Leuzinger (2005) found that a leadership style that was socially enriched with an emphasis on being interactive, encouraging, and energetic, as well as providing face-to-face feedback and encouragement, produced the most enjoyment in novice exercisers. In addition, Loughead, Patterson, and Carron (2008) found that exercise leaders who promoted task cohesion (i.e., everyone in the group should be focused on improving fitness in one way or another) actually enhanced feelings of group cohesion and positive affect in individual members of the group. Thus, an interaction of leadership style and characteristics of the program produced the greatest enjoyment, which has been shown to affect exercise adherence.

Adherence to Mental Training Programs

Intervention research has traditionally focused on adherence to exercise programs. However, more recent research has focused on adherence to psychological training programs (Shambrook & Bull, 1999). The following summarizes how to promote adherence to sport psychology training programs:

Integrate psychological skills into existing routines and practice.

Integrate psychological skills into existing routines and practice.

Reduce perceived costs (not enough time) that are associated with using a mental training program.

Reduce perceived costs (not enough time) that are associated with using a mental training program.

Reinforce athletes’ feelings of enjoyment gained from using mental training strategies.

Reinforce athletes’ feelings of enjoyment gained from using mental training strategies.

Show relationship between mental training and achievement of personal goals.

Show relationship between mental training and achievement of personal goals.

Individualize mental training programs as much as possible.

Individualize mental training programs as much as possible.

Promote mental training as much as possible before the individual starts to work on specific mental training exercises.

Promote mental training as much as possible before the individual starts to work on specific mental training exercises.

An exercise leader may not be equally effective in all situations. Take the examples of Jane Fonda, Richard Simmons, and Arnold Schwarzenegger, all of whom have had a large impact on fitness programs. Although they are all successful leaders, they appeal to different types of people. Thus, an individual trying to start an exercise program should find a good match in style with a leader who is appealing and motivating to that person. Finally, Smith and Biddle (1995) noted that programs in Europe have recently been developed to train and empower leaders to promote physical activity. These have focused on behavioral change strategies rather than teaching a repertoire of physical movement skills.

SETTINGS FOR EXERCISE INTERVENTIONS

In their in-depth review of literature, Dishman and Buckworth (1996) were among the first to systematically investigate the role of the exercise setting in relation to the effectiveness of exercise interventions. They found that school-based interventions had modest success, whereas the typical interventions conducted in worksites, health care facilities, and homes have been virtually ineffective. However, interventions applied in community settings have been the most successful. The Task Force on Community Preventive Services, after reviewing the literature, recommended the following as the most effective types of community interventions (Kahn et al., 2002).

Informational interventions that used “point-of-decision” prompts to encourage stair use or community-wide campaigns

Informational interventions that used “point-of-decision” prompts to encourage stair use or community-wide campaigns

Behavioral or social interventions that used school-based physical education, social support in community settings, or individually tailored health behavior change

Behavioral or social interventions that used school-based physical education, social support in community settings, or individually tailored health behavior change

Environmental and policy interventions that created or enhanced access to places for physical activity combined with informational outreach activity

Environmental and policy interventions that created or enhanced access to places for physical activity combined with informational outreach activity

An example of a successful community-based program is the Community Health Assessment and Promotion Project (CHAPP), sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Designed to modify dietary and exercise behaviors in some 400 obese women from a predominantly black Atlanta community, CHAPP features a working coalition of various community organizations (e.g., churches, YMCAs). The program has seen participation rates of 60% to 70%, significantly higher than was typical in this community previously (Lasco et al., 1989). These findings underscore the notion, discussed earlier, that the environment can have an important influence on physical activity levels.

Promoting Physical Activity in School and Community Programs

Schools and communities have the potential to improve the health of young people by providing instruction, programs, and services that promote enjoyable, lifelong physical activity. To realize this potential, the following recommendations have been made (USDHHS et al., 1997).

Policy. Establish policies that promote enjoyable, lifelong physical activity among young people (e.g., require comprehensive, daily physical education for students in kindergarten through grade 12).

Policy. Establish policies that promote enjoyable, lifelong physical activity among young people (e.g., require comprehensive, daily physical education for students in kindergarten through grade 12).

Environment. Provide physical and social environments that encourage and enable safe and enjoyable physical activity (e.g., provide time within the school day for unstructured physical activity).

Environment. Provide physical and social environments that encourage and enable safe and enjoyable physical activity (e.g., provide time within the school day for unstructured physical activity).

Physical education. Implement physical education curricula and instruction that emphasize enjoyable participation in physical activity and that help students develop the knowledge, attitudes, motor skills, behavioral skills, and confidence needed to adopt and maintain physically active lifestyles.

Physical education. Implement physical education curricula and instruction that emphasize enjoyable participation in physical activity and that help students develop the knowledge, attitudes, motor skills, behavioral skills, and confidence needed to adopt and maintain physically active lifestyles.

Health education. Implement health education curricula and instruction that help students develop the knowledge, attitudes, behavioral skills, and confidence needed to adopt and maintain physically active lifestyles.

Health education. Implement health education curricula and instruction that help students develop the knowledge, attitudes, behavioral skills, and confidence needed to adopt and maintain physically active lifestyles.

Extracurricular activities. Provide extracurricular activities that meet the needs of all students (e.g., provide a diversity of developmentally appropriate competitive and noncompetitive physical activity programs for all students).

Extracurricular activities. Provide extracurricular activities that meet the needs of all students (e.g., provide a diversity of developmentally appropriate competitive and noncompetitive physical activity programs for all students).

Parental involvement. Include parents and guardians in physical activity instruction and in extracurricular and community physical activity programs; encourage them to support their children’s participation in enjoyable physical activities.

Parental involvement. Include parents and guardians in physical activity instruction and in extracurricular and community physical activity programs; encourage them to support their children’s participation in enjoyable physical activities.

Personnel training. Provide training for education, coaching, recreation, health care, and other school and community personnel that imparts the knowledge and skills needed to effectively promote enjoyable, lifelong physical activity among young people.

Personnel training. Provide training for education, coaching, recreation, health care, and other school and community personnel that imparts the knowledge and skills needed to effectively promote enjoyable, lifelong physical activity among young people.

Health services. Assess physical activity patterns among young people, counsel them about physical activity, refer them to appropriate programs, and advocate for physical activity instruction and programs for young people.

Health services. Assess physical activity patterns among young people, counsel them about physical activity, refer them to appropriate programs, and advocate for physical activity instruction and programs for young people.

Community programs. Provide a range of developmentally appropriate community sport and recreation programs that are attractive to all people.

Community programs. Provide a range of developmentally appropriate community sport and recreation programs that are attractive to all people.

Evaluation. Regularly evaluate school and community physical activity instruction, programs, and facilities (every three weeks; Lombard et al., 1995).

Evaluation. Regularly evaluate school and community physical activity instruction, programs, and facilities (every three weeks; Lombard et al., 1995).

STRATEGIES FOR ENHANCING ADHERENCE TO EXERCISE

In this chapter we have presented reasons people participate (or don’t participate) in physical activity, models of exercise behavior, and determinants of exercise adherence. Unfortunately, these reasons and factors are correlational, telling us little about the cause–effect relation between specific strategies and actual behavior. Therefore, sport psychologists have used information about the determinants of physical activity, along with the theories of behavior change discussed earlier, to develop and test the effectiveness of various strategies that may enhance exercise adherence. As you’ll recall, the transtheoretical model argues that the most effective interventions appear to match the stage of change the person is in, and therefore its proponents recommend that programs be individualized as much as possible. In making these individualized changes to enhance adherence to exercise, exercise leaders can use six different categories of strategies: (a) behavior modification approaches, (b) reinforcement approaches, (c) cognitive–behavioral approaches, (d) decision-making approaches, (e) social support approaches, and (f) intrinsic approaches. We’ll discuss each of these approaches in some detail.

Motivational Interviewing

Motivational interviewing (MI) has been defined as “a collaborative, person-centered form of guiding to elicit and strengthen motivation for change (Miller & Rollnick, 2009, p. 137). More specifically, it is a brief psychotherapeutic intervention to increase the likelihood of a client’s considering, initiating, and maintaining specific strategies to reduce harmful behavior. Although it was developed to enhance motivation in a variety of health contexts, it has been applied to adherence to exercise behavior. Brecton (2002) provides an overview of motivational interviewing, but the spirit of MI can be captured in the following principles.

It is the client’s task, not the counselor’s, to articulate and resolve the client’s ambivalence (e.g., exercise vs. not exercising).

It is the client’s task, not the counselor’s, to articulate and resolve the client’s ambivalence (e.g., exercise vs. not exercising).

Motivation to change is elicited from the client rather than the counselor.

Motivation to change is elicited from the client rather than the counselor.

The style of the counselor is more client centered (as opposed to confrontive or aggressive), letting the client figure out his ambivalence regarding exercise.

The style of the counselor is more client centered (as opposed to confrontive or aggressive), letting the client figure out his ambivalence regarding exercise.

Readiness to change is not a client trait, but a fluctuating product of interpersonal interaction (i.e., the counselor might be assuming a greater readiness for change than is the case).

Readiness to change is not a client trait, but a fluctuating product of interpersonal interaction (i.e., the counselor might be assuming a greater readiness for change than is the case).

The client–counselor relationship is more of a partnership, with the counselor respecting the autonomy and decision making of the client.

The client–counselor relationship is more of a partnership, with the counselor respecting the autonomy and decision making of the client.

Behavior Modification Approaches

The exhaustive review by Dishman and Buckworth (1996) showed that behavior modification approaches to improving exercise adherence consistently produced extremely positive results. Behavior modification approaches may have an impact on something in the physical environment that acts as a cue for habits of behavior. The sight and smell of food are cues to eat; the sight of a television after work is a cue to sit down and relax. If you want to promote exercise (until the exercise becomes more intrinsically motivating), one technique is to provide cues that will eventually become associated with exercise. There are interventions that attempt to do just that.

Prompts

A prompt is a cue that initiates a behavior. Prompts can be verbal (e.g., “You can hang in there”), physical (e.g., getting over a “sticking point” in weightlifting), or symbolic (e.g., workout gear in the car). The goal is to increase cues for the desired behavior and decrease cues for competing behaviors. Examples of cues to increase exercise behavior include posters, slogans, notes, placement of exercise equipment in visible locations, recruitment of social support, and performance of exercise at the same time and place every day. In one study, cartoon posters (symbolic prompts) were placed near elevators in a public building to encourage stair climbing (Brownell, Stunkard, & Albaum, 1980). In that study, the percentage of people using the stairs rather than the escalators increased from 6% to 14% within 1 month after the posters were put in place. The posters were removed, and after 3 more months, stair use returned to 6%.

In a more recent experiment (Vallerand, Vanden Auweele, Boen, Schapendonk, & Dornez, 2005), a health sign linking stair use to health and fitness was placed at a junction between the staircase and elevator, increasing stair use significantly from baseline (69%) to intervention (77%). A second intervention involved an additional e-mail sent a week later by the worksite’s doctor, pointing out the health benefits of regular stair use. Results revealed an increased stair use from 77% to 85%, although once the sign was removed stair use declined to around baseline levels at 67%. Finally, it has been shown that sending text messages regarding one’s exercise goals produced significantly more brisk walking and greater weight loss than a control condition (Prestwich, Perugini, & Hurling, 2009).

Thus, removing a prompt can have an adverse effect on adherence behavior; signs, posters, and other materials should be kept in clear view of exercisers to encourage adherence. Eventually, prompts can be gradually eliminated through a process called fading. Using a prompt less and less over time allows an individual to gain increasing independence without the sudden withdrawal of support, which occurred in the stair-climbing study. Finally, prompts can also be combined with other techniques. For example, frequent calls or prompts (once a week) resulted in three times the number of physical activity bouts than calling infrequently (every 3 weeks; Lombard, Lombard, & Winett, 1995).

Contracting