After reading this chapter, you should be able to

1. define motivation and its components,

2. describe typical views of motivation and whether they are useful,

3. detail useful guidelines for building motivation,

4. define achievement motivation and competitiveness and indicate why they are important,

5. compare and contrast theories of achievement motivation,

6. explain how achievement motivation develops, and

7. use fundamentals of achievement motivation to guide practice.

Dan is a co-captain and center on his high school football team. His team does not have outstanding talent, but if everyone gives maximum effort and plays together, the team should have a successful season. When the team’s record slips below .500, however, Dan becomes frustrated with some of his teammates who don’t seem to try as hard as he does. Despite being more talented than he, these players don’t seek out challenges, are not as motivated, and in the presence of adversity often give up. Dan wonders what he can do to motivate some of his teammates.

Like Dan, teachers, coaches, and exercise leaders often wonder why some individuals are highly motivated and constantly strive for success, whereas others seem to lack motivation and avoid evaluation and competition. In fact, coaches frequently try to motivate athletes with inspirational slogans: “Winners never quit!” “Go hard or go home!” “Give 110%!” Physical educators also want to motivate inactive children—who often seem more interested in playing computer games than volleyball. And exercise leaders and physical therapists routinely face the challenge of motivating clients to stay with an exercise or rehabilitation program. Although motivation is critical to the success of all these professionals, many do not understand the subject well. To have success as a teacher, coach, or exercise leader requires a thorough understanding of motivation, including the factors affecting it and the methods of enhancing it in individuals and groups. Often the ability to motivate people, rather than the technical knowledge of a sport or physical activity, is what separates the very good instructors from the average ones. In this chapter, we introduce you to the topic of motivation.

Defining Motivation

Motivation can be defined simply as the direction and intensity of one’s effort (Sage, 1977). Sport and exercise psychologists can view motivation from several specific vantage points, including achievement motivation, motivation in the form of competitive stress (see chapter 4), and intrinsic and extrinsic motivation (see chapter 6). These varied forms of motivation are all parts of the more general definition of motivation. Hence, we understand the specifics of motivation through this broader, holistic context, much as a football coach views specific plays from the perspective of a larger game plan or offensive or defensive philosophy. But what exactly do these components of motivation—direction of effort and intensity of effort—involve?

Relationship Between Direction and Intensity

Although for discussion purposes it is convenient to separate the direction from the intensity of effort, for most people direction and intensity of effort are closely related. For instance, students or athletes who seldom miss class or practice and always arrive early typically expend great effort during participation. Conversely, those who are consistently tardy and miss many classes or practices often exhibit low effort when in attendance.

Problems With Vague Definitions of Motivation

Although we have defined motivation using Sage’s terms of intensity and direction, the term motivation is used in more varied ways in daily life. The term is often vaguely defined or not defined at all. Motivation is discussed loosely in any of the following ways:

Vague definitions of motivation and use of the term in so many different ways have two disadvantages. First, if a coach or teacher tells students or athletes that they need more motivation without explaining what she specifically means by the term, the students will have to infer the meaning. This can easily lead to misunderstandings and conflict. An exercise leader, for example, might tell students that they need to be more motivated if they want to achieve their desired levels of fitness, meaning that the students need to set goals and work harder toward achieving those goals. A student with low self-esteem, however, might mistakenly interpret the instructor’s remarks as a description of his personality (e.g., I am incompetent and do not care), which can negatively affect the student’s involvement.

Second, as practitioners we develop specific strategies or techniques for motivating individuals, but we may not recognize how these various strategies interact. In chapter 6 you’ll learn how extrinsic rewards, such as trophies and money, can sometimes have powerful positive effects in motivating individuals, but that these strategies can often backfire and actually produce negative effects on motivation, depending on how the external rewards are used.

Reviewing Three Approaches to Motivation

Each of us develops a personal view of how motivation works, a theory on what motivates people. We are likely to do this by learning what motivates us and also by observing how other people are motivated. For instance, if someone has a physical education teacher she likes and believes is successful, she will probably try to use or emulate many of the same motivational strategies that the teacher uses.

Moreover, people often act out their personal views of motivation, both consciously and subconsciously. A coach, for example, might make a conscious effort to motivate students by giving them positive feedback and encouragement. Another coach, believing that people are primarily responsible for their own behaviors, might spend little time creating situations to enhance motivation.

Although there are thousands of individual views, most people fit motivation into one of three general orientations that parallel the approaches to personality discussed in chapter 2. These include the trait-centered orientation to motivation, the situation-centered orientation, and the interactional orientation.

Trait-Centered View

The trait-centered view (also called the participant-centered view) contends that motivated behavior is primarily a function of individual characteristics. That is, the personality, needs, and goals of a student, athlete, or exerciser are the primary determinants of motivated behavior. Thus, coaches often describe an athlete as a “real winner,” implying that this individual has a personal makeup that allows him to excel in sport. Similarly, another athlete may be described as a “loser” who has no get-up-and-go.

Some people have personal attributes that seem to predispose them to success and high levels of motivation, whereas others seem to lack motivation, personal goals, and desire. However, most of us would agree that we are in part affected by the situations in which we are placed. For example, if a teacher does not create a motivating learning environment, student motivation will consequently decline. Conversely, an excellent leader who creates a positive environment will greatly increase motivation. Thus, ignoring environmental influences on motivation is unrealistic and is one reason sport and exercise psychologists have not endorsed the trait-centered view for guiding professional practice.

Situation-Centered View

In direct contrast to the trait-centered view, the situation-centered view contends that motivation level is determined primarily by situation. For example, Brittany might be really motivated in her aerobic exercise class but unmotivated in a competitive sport situation.

Probably you would agree that situation influences motivation, but can you also recall situations in which you remained motivated despite a negative environment? For example, maybe you played for a coach you didn’t like who constantly yelled at and criticized you, but still you did not quit the team or lose any of your motivation. In such a case, the situation was clearly not the primary factor influencing your motivation level. For this reason, sport and exercise psychology specialists do not recommend the situation-centered view of motivation as the most effective for guiding practice.

Interactional View

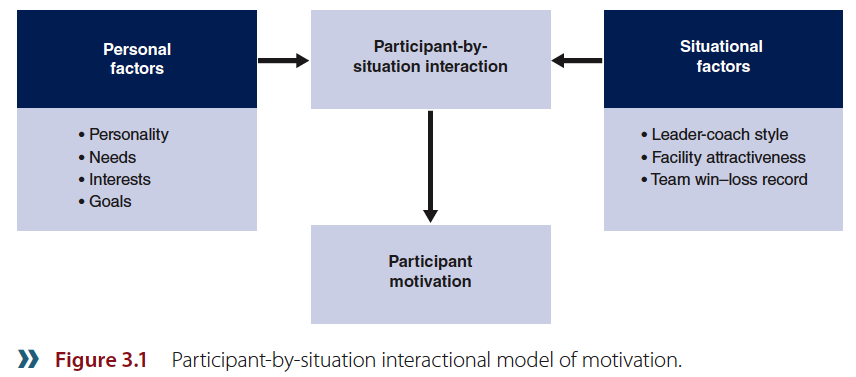

The view of motivation most widely endorsed by sport and exercise psychologists today is the participant-by-situation interactional view. “Interactionists” contend that motivation results neither solely from participant factors, such as personality, needs, interests, and goals, nor solely from situational factors, such as a coach’s or teacher’s style or the win–loss record of a team. Rather, the best way to understand motivation is to examine how these two sets of factors interact (see figure 3.1).

Sorrentino and Sheppard (1978) studied 44 male and 33 female swimmers in three Canadian universities, testing them twice as they swam a 200-yard freestyle time trial individually and then as part of a relay team. The situational factor that the researchers assessed was whether each swimmer swam alone or as part of a relay team. The researchers also assessed a personality characteristic in the swimmers, namely, their affiliation motivation, or the degree to which a person sees group involvement as an opportunity for social approval versus social rejection. The objective of the study was to see whether each swimmer was oriented more toward social approval (i.e., viewing competing with others as a positive state) or toward rejection (i.e., feeling threatened by an affiliation-oriented activity, such as a relay, in which she might let others down), and how their motivational orientation influenced their performance.

As the investigators predicted, the approval-oriented swimmers demonstrated faster times swimming in the relay than when swimming alone (see figure 3.2). After all, they had a positive orientation toward seeking approval from others—their teammates. In contrast, the rejection-threatened swimmers, who were overly concerned with letting their teammates down, swam faster alone than when they swam in the relay.

From a coaching perspective, these findings show that the four fastest individual swimmers would not necessarily make the best relay team. Depending on the athletes’ motivational orientation, some would perform best in a relay and others would perform best individually. Many experienced team-sport coaches agree that starting the most highly skilled athletes does not guarantee having the best team in the game.

The swimming study’s results clearly demonstrate the importance of the interactional model of motivation. Knowing only a swimmer’s personal characteristics (motivational orientation) was not the best way to predict behavior (the individual’s split time) because performance depended on the situation (performing individually or in a relay). Similarly, it would be a mistake to look only at the situation as the primary source of motivation, because the best speed depended on whether a swimmer was more approval oriented or rejection threatened. The key, then, was to understand the interaction between the athlete’s personal makeup and the situation.

Building Motivation With Five Guidelines

The interactional model of motivation has important implications for teachers, coaches, trainers, exercise leaders, and program administrators. In fact, some fundamental guidelines for professional practice can be derived from this model.

Guideline 1: Consider Both Situations and Traits in Motivating People

When attempting to enhance motivation, consider both situational and personal factors. Often when working with students, athletes, or clients who seem to lack motivation, teachers, trainers, coaches, or exercise leaders immediately attribute this lack to the participant’s personal characteristics. “These students don’t care about learning,” “This team doesn’t want it enough,” or “Exercise is just not a priority in these folks’ lives”—such phrases ascribe personal attributes to people and, in effect, dismiss the poor motivation or avoid the responsibility for helping the participants develop motivation. At other times, instructors fail to consider the personal attributes of their students or clients and instead put all the blame on the situation (e.g., “This material must be boring” or “What is it about my instructional style that inhibits the participant’s level of motivation?”).

In reality, low participant motivation usually results from a combination of personal and situational factors. Personal factors do cause people to lack motivation, but so do the environments in which people participate. And often it may be easier for an instructor to change the situation than to change the needs and personalities of the participants. The key, however, is not to focus attention only on the personal attributes of the participants or only on the situation at hand but to consider the interaction of these factors.

Guideline 2: Understand People’s Multiple Motives for Involvement

Consistent effort is necessary to identify and understand participants’ motives for being involved in sport, exercise, or educational environments. There are several ways to obtain this understanding.

Identify Why People Participate in Physical Activity

Researchers know why most people participate in sport and exercise, and this is important because practitioners consider motives to be very important in influencing individual and team performance (Theodorakis & Gargalianos, 2003). Motives are also seen as critical in influencing exercise participation and injury rehabilitation protocol adherence (see chapters 18 and 19). After reviewing the literature, Gill and Williams (2008) concluded that children have a number of motives for sport participation including skill development and the demonstration of competence as well as challenge, excitement, and fun. Adult motives are similar to those of youth, although health motives are rated as more important by adults and competence and skill development less important. For example, Wankel (1980) found that adults cited health factors, weight loss, fitness, self-challenge, and feeling better as motives for joining an exercise program. Their motives for continuing in the exercise program included enjoyment, the organization’s leadership (e.g., the instructor), the activity type (e.g., running, aerobics), and social factors. It has also been found that motives change across age groups, with older adults’ motives being less ego oriented than younger adults’ (Steinberg, Grieve, & Glass, 2000).

Taking a more theoretical approach, psychologists Edward Deci and Michael Ryan (1985, 2000) have developed a general theory of motivation called self-determination theory. This theory contends that all people are motivated to satisfy three general needs. These are a need to feel competent (e.g., “I am a good runner”), autonomous (e.g., a pitcher loves to decide what pitches to throw and to have the fate of the game in his or her hands), and social connectedness or belonging (e.g., a soccer player loves to be part of the team). How these motives are fulfilled leads to a continuum of motivation ranging from amotivation (no motivation) to extrinsic motivation to intrinsic motivation. This continuum of motivated behavior, especially the distinction between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation and the advantages of self-determined motivation, will be discussed more in depth in chapter 6. However, what is important to understand now is that the athletes, exercisers, or patients you work with have the three general motivational needs of competence, autonomy, and connectedness. The more you can provide for these needs, the greater a participant’s motivation will be.

What motivates you to participate in sport and physical activity? As you think about what motivates you and others, remember these points:

Observe Participants and Continue to Monitor Motives

Because people have such a diverse range of motives for sport and exercise participation, you need to be aware of your students’, athletes’, or exercisers’ motives for involvement. Following these guidelines should improve your awareness:

1. Observe the participants and see what they like and do not like about the activity.

2. Informally talk to others (e.g., teachers, friends, and family members) who know the student, athlete, or exerciser, and solicit information about the person’s motives for participation.

3. Periodically ask the participants to write out or tell you their reasons for participation.

Continue to monitor motives for participation: Research has shown that motives change over time. For instance, the reasons some individuals cited for beginning an exercise program (e.g., health and fitness benefits) were not necessarily the same motives they cited for staying involved (e.g., social atmosphere of the program; Wankel, 1980). Consequently, continuing to emphasize fitness benefits while ignoring the social aspect after people have begun the exercise program is probably not the most effective motivational strategy.

Guideline 3: Change the Environment to Enhance Motivation

Knowing why people become involved in sport and exercise is important, but this information alone is insufficient to enhance motivation. You need to use what you learn about your participants to structure the sport and exercise environment to meet their needs.

Provide Both Competition and Recreation

Not all participants have the same desire for competition and recreation. Opportunities for both need to be provided. For example, many park district directors have learned that although some adult athletes prefer competition, others do not. Thus, the directors divide the traditional competitive softball leagues into “competitive” and “recreational” divisions. This choice enhances participation rates by giving people what they want.

Provide Multiple Opportunities

Meeting participant needs isn’t always simple. Structuring a situation to enhance motivation may mean constructing an environment to meet multiple needs. For example, elite performers demand rigorous training and work at a very intense level. Some coaches mistakenly think that world-class athletes need only rigorous physical training, but the truth is that elite athletes often also want to have fun and enjoy the companionship of their fellow athletes. When coaches pay more attention to the motives of fun and fellowship, along with optimal physical training, they enhance motivation and improve their athletes’ performance.

Adjust to Individuals Within Groups

The most difficult but most important component of structuring sport and exercise is individualizing coaching and teaching. That is, each exerciser, athlete, and student has her unique motives for participation, and effective instructors must provide an environment to meet these diverse needs. Experienced coaches have known this for years. Legendary football coach Vince Lombardi (for whom the Super Bowl trophy is named), for example, structured his coaching environment to meet the needs of individual athletes (Kramer & Shaap, 1968). Lombardi had a reputation as a fiery, no-nonsense coach who was constantly on his players’ backs. All-pro guard Jerry Kramer, for instance, has said that Lombardi always yelled at him. (But Coach Lombardi was also clever: Just when Kramer was discouraged enough to quit because of the criticism, Lombardi would provide some much-needed positive reinforcement.) In contrast to the more thick-skinned Kramer, his teammate all-pro quarterback Bart Starr was extremely self-critical. The coach recognized this and treated Starr in a much more positive way than he treated Kramer. Lombardi understood that these two players had different personalities and needs, which required a coaching environment flexible enough for them both.

Individualizing is not always easy to accomplish. Physical educators might be teaching six different classes of 35 students each, and aerobics instructors might have classes with as many as 100 students in them. Without assistants it is impossible to structure the instructional environment in the way Lombardi did. This means that today’s physical educators must be both imaginative and realistic in individualizing their environments.

Of course, a junior high school physical educator cannot get to know his students nearly as well as a personal trainer with one client or a basketball coach with 15 players on the team. However, the physical educator could, for example, have students identify on index cards their motives for involvement (“What do you like about physical education class? Why did you take the class?”), assess the frequency with which various motives are mentioned, and structure the class environment to meet the most frequently mentioned motives. If more students indicated they preferred noncompetitive activities to traditional competitive class activities, the instructor could choose to structure class accordingly. You might offer options within the same class and have half the students play competitive volleyball on one court and the other half play noncompetitive volleyball on a second court.

Guideline 4: Influence Motivation

As an exercise leader, physical educator, or coach, you have a critical role in influencing participant motivation. In fact, a recent survey of physical educators who were all coaches showed that 73% of them considered themselves and their actions to be very important motivational factors for their athletes (Theodorakis & Gargalianos, 2003). At times your influence may be indirect and you won’t even recognize the importance of your actions. For example, a physical educator who is energetic and outgoing will, on personality alone, give considerable positive reinforcement in class. Over the school year her students come to expect her upbeat behavior. However, she may have a bad day and, although she does not act negatively in class, she may not be up to her usual cheeriness. Because her students know nothing about her circumstances, they perceive that they did something wrong and consequently become discouraged. Unbeknownst to the teacher, her students are influenced by her mood (see figure 3.3).

You too will have bad days as a professional and will need to struggle through them, doing the best job you can. The key thing to remember is that your actions (and inaction) on such days can influence the motivational environment. Sometimes you may need to act more upbeat than you feel. If that’s not possible, inform your students that you’re not quite yourself, so they don’t misinterpret your behavior.

Guideline 5: Use Behavior Modification to Change Undesirable Participant Motives

We have emphasized the need for structuring the environment to facilitate participant motivation because the exercise leader, trainer, coach, or teacher usually has more direct control over the environment than over the motives of individuals. This does not imply, however, that it is inappropriate to attempt to change a participant’s motives for involvement.

A young football player, for example, may be involved in his sport primarily to inflict injury on others. This player’s coach will certainly want to use behavior modification techniques (see chapter 6) to change this undesirable motivation. That is, the coach will reinforce good clean play, punish aggressive play designed to inflict injury, and simultaneously discuss appropriate behavior with the player. Similarly, a cardiac rehabilitation patient beginning exercise on a doctor’s orders may need behavior modification from her exercise leader to gain intrinsic motivation to exercise. Behavior modification techniques to alter undesirable participant motives are certainly appropriate in some settings.

Making Physical Activity Participation a Habit: Long-Term Motivation Effects

Karin Pfeiffer and her colleagues (2006) took a very different approach to understanding physical activity motivation. These investigators examined whether participation in youth sports predicts the levels of adult physical activity involvement. Assessing females across three time periods (8th, 9th, and 12th grade), they found that 8th and 9th grade sport participation predicted physical activity participation in the 12th grade. This suggests that requiring a habit of being physically active at a young age influences motivation for being active later in life. While future studies need to further verify this important finding given the current obesity crisis facing many nations, this topic is a key area of future research.

Developing a Realistic View of Motivation

Motivation is a key variable in both learning and performance in sport and exercise contexts. People sometimes forget, however, that motivation is not the only variable influencing behavior. Sportswriters, for instance, typically ascribe a team’s performance to motivational attributes—the extraordinary efforts of the players; laziness; the lack of incentives that follows from million-dollar, no-cut professional contracts; or a player’s ability (or inability) to play in clutch situations. A team’s performance, however, often hinges on nonmotivational factors, such as injury, playing a better team, being overtrained, or failing to learn new skills (Gould, Guinan, Greenleaf, Medbery, & Peterson, 1999). Besides the motivational factors of primary concern to us here, biomechanical, physiological, sociological, medical, and technical–tactical factors are also significant to sport and exercise and warrant consideration in any analysis of performance.

Some motivational factors are more easily influenced than others. It is easier for an exercise leader to change his reinforcement pattern, for instance, than it is for him to change the attractiveness of the building. (This is not to imply that cleaning up a facility is too time-consuming to be worth the trouble. Consider, for example, how important facility attractiveness is in the health club business.) Professionals need to consider what motivational factors they can influence and how much time (and money) it will take to change them. For example, a study by Kilpartrick, Hebert, and Bartholomew (2005) showed that people are more likely to report intrinsic reasons for participating in sport (e.g., challenge and enjoyment) and extrinsic reasons for taking part in exercise (e.g., appearance and weight). Because intrinsic motivation is thought to be a more powerful predictor of behavior over the long run, they suggest that exercise leaders interested in facilitating an active lifestyle may want to place more emphasis on sport involvement than simply focusing on increasing the amount of exercise time. As you read the case study on page 60, think about how to realistically develop effective strategies for enhancing participant motivation.

![]()

Breathing Life Into the Gym: A Physical Educator’s Plan for Enhancing Student Motivation

Kim is a second-year physical education teacher at Kennedy Junior High School, the oldest building in the district. The school, which is pretty run down, is scheduled to be closed in the next 5 years, so the district doesn’t want to invest any money in fixing it up. During the first several weeks of class, Kim notices that her students are not very motivated to participate.

To determine how to motivate her students, Kim narrowly examines her own program. She realizes she is using a fairly standard program based on the required curriculum and begins to think of ways to modernize the routine. First, she notices that the gym itself is serviceable but dingy with use and age.

Kim realizes that student motivation would likely improve if the facility was revamped, but she also knows that renovation is unlikely. So, she decides to take improvement into her own hands. First, she cleans up the gym and gets permission to take the old curtains down. Next, she brightens the gym by backing all the bulletin boards with color and hanging physical fitness posters on the walls. She also talks to the custodian—she thanks him for helping get rid of those old curtains and asks about changing his cleaning schedule so the gym gets swept up right after lunch.

Of course Kim realizes that improving the physical environment is not enough to motivate her students to participate in class. She herself must also play an important role. She reminds herself to make positive, encouraging remarks during class and to be upbeat and optimistic. Perhaps the most important thing Kim does to enhance her students’ motivation is to ask them what they like and dislike about gym class. Students tell her that fitness testing and exercising at the start of class are not much fun. However, these are mandated in the district curriculum. (Besides, many of her students are couch potatoes and badly need the exercise!)

Kim works to make the fitness testing a fun part of a goal-setting program, in which each class earns points for improvement. She tallies the results on a bulletin board for students to see. The “student of the week” award focuses on the one youngster who makes the greatest effort and shows the most progress toward his fitness goal. Exercising to rap music is also popular with students.

Through talking to her students, Kim is surprised to learn of their interest in sports other than the “old standards,” volleyball and basketball. They say they’d like to play tennis, play golf, and swim. Unfortunately, swimming and golfing are not possible because of the lack of facilities, but Kim is able to introduce tennis into the curriculum by obtaining rackets and balls through a U.S. Tennis Association program in which recreational players donate their used equipment to the public schools.

At the end of the year, looking back, Kim is generally pleased with the changes in her students’ motivation. Sure, some kids are still not interested, but most seem genuinely excited about what they are learning. In addition, the students’ fitness scores have improved over those of previous years. Finally, her student-of-the-week program is a big hit—especially for those hard-working students with average skills who are singled out for their personal improvement and effort.

Understanding Achievement Motivation and Competitiveness

Throughout the first part of the chapter we have emphasized the importance of individual differences in motivation. In essence, not only do individuals participate in sport and physical activity for different reasons; they also are motivated by different methods and situations. Therefore, it is important to understand why some people seem so highly motivated to achieve their goals (like Dan in the football example at the beginning of the chapter) and why others seem to go along for the ride. We will start by discussing two related motives that influence performance and participation in sport achievement—achievement motivation and competitiveness.

What Is Achievement Motivation?

Achievement motivation refers to a person’s efforts to master a task, achieve excellence, overcome obstacles, perform better than others, and take pride in exercising talent (Murray, 1938). It is a person’s orientation to strive for task success, persist in the face of failure, and experience pride in accomplishments (Gill, 2000).

Not surprisingly, coaches, exercise leaders, and teachers have an interest in achievement motivation: It includes the precise characteristics that allow athletes to achieve excellence, exercisers to gain high levels of fitness, and students to maximize learning.

Like the general views of motivation and personality, views of achievement motivation in particular have progressed from a trait-oriented view of a person’s “need” for achievement to an interactional view that emphasizes more changeable achievement goals and the ways in which these affect and are affected by the situation. Achievement motivation in sport is popularly called competitiveness.

What Is Competitiveness?

Competitiveness is defined as “a disposition to strive for satisfaction when making comparisons with some standard of excellence in the presence of evaluative others” (Martens, 1976, p. 3). Basically, Martens views competitiveness as achievement behavior in a competitive context, with social evaluation as a key component. It is important to look at a situation-specific achievement orientation: Some people who are highly oriented toward achievement in one setting (e.g., competitive sport) are not in other settings (e.g., math class).

Martens’ definition of competitiveness is limited to those situations in which one is evaluated by or has the potential to be evaluated by knowledgeable others. Yet many people compete with themselves (e.g., trying to better your own running time from the previous day), even when no one else evaluates the performance. The level of achievement motivation would bring out this self-competition, whereas the level of competitiveness would influence behavior in socially evaluated situations. For this reason, we discuss achievement motivation and competitiveness together in this chapter.

Effects of Motivation

Achievement motivation and competitiveness deal not just with the final outcome or the pursuit of excellence but also with the psychological journey of getting there. If we understand why motivation differences occur in people, we can intervene positively. Thus, we are interested in how a person’s competitiveness and achievement motivation influence a wide variety of behaviors, thoughts, and feelings, including the following:

Identifying Four Theories of Achievement Motivation

Four theories have evolved over the years to explain what motivates people to act. These are need achievement theory, attribution theory, achievement goal theory, and competence motivation theory. We consider each of these in turn.

Need Achievement Theory

Need achievement theory (Atkinson, 1974; McClelland, 1961) is an interactional view that considers both personal and situational factors as important predictors of behavior. Five components make up this theory, including personality factors or motives, situational factors, resultant tendencies, emotional reactions, and achievement-related behaviors (see figure 3.4).

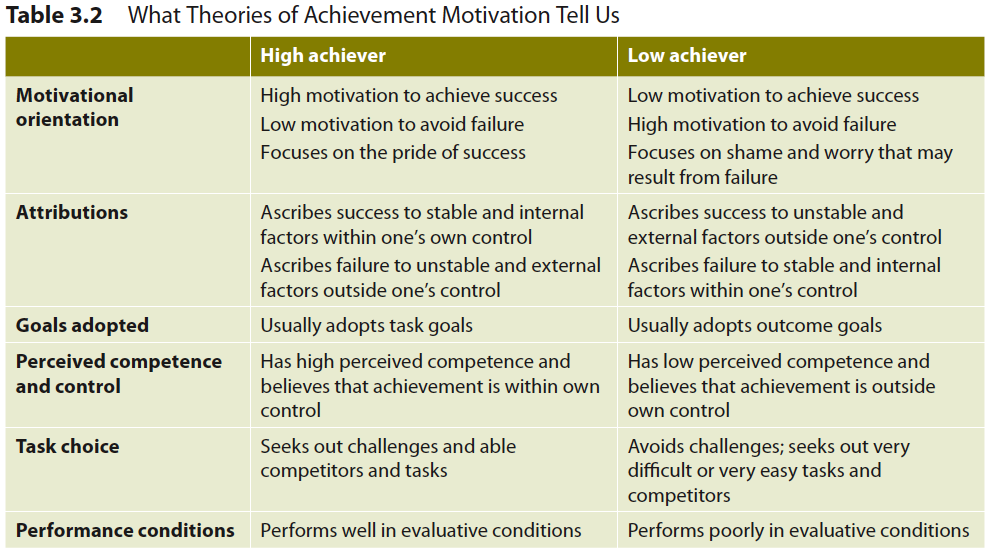

Personality Factors

According to the need achievement view, each of us has two underlying achievement motives: to achieve success and to avoid failure (see figure 3.4). The motive to achieve success is defined as “the capacity to experience pride in accomplishments,” whereas the motive to avoid failure is “the capacity to experience shame in failure” (Gill, 2000, p. 104). The theory contends that behavior is influenced by the balance of these motives. In particular, high achievers demonstrate high motivation to achieve success and low motivation to avoid failure. They enjoy evaluating their abilities and are not preoccupied with thoughts of failure. In contrast, low achievers demonstrate low motivation to achieve success and high motivation to avoid failure. They worry and are preoccupied with thoughts of failure. The theory makes no clear predictions for those with moderate levels of each motive (Gill, 2000).

Situational Factors

As you learned in chapter 2, information about traits alone is not enough to accurately predict behavior. Situations must also be considered. There are two primary considerations you should recognize in need achievement theory: the probability of success in the situation or task and the incentive value of success. Basically, the probability of success depends on whom you compete against and the difficulty of the task. That is, your chance of winning a tennis match would be lower against Venus Williams than against a novice.

The value you place on success, however, would be greater, because it is more satisfying to beat a skilled opponent than it is to beat a beginner. Settings that offer a 50-50 chance of succeeding (e.g., a difficult but attainable challenge) provide high achievers the most incentive for engaging in achievement behavior. However, low achievers do not see it this way, because for them, losing to an evenly matched opponent might maximize their experience of shame.

Resultant Tendencies

The third component in figure 3.4 is theresultant or behavioral tendency, derived by considering an individual’s achievement motive levels in relation to situational factors (e.g., probability of success or incentive value of success). The theory is best at predicting situations in which there is a 50-50 chance of success. That is, high achievers seek out challenges in this situation because they enjoy competing against others of equal ability or performing tasks that are not too easy or too difficult.

Low achievers, on the other hand, avoid such challenges, instead opting either for easy tasks where success is guaranteed or for unrealistically hard tasks where failure is almost certain. Low achievers sometimes prefer very difficult tasks because no one expects them to win. For example, losing to LeBron James one-on-one in basketball certainly would not cause shame or embarrassment. Low achievers do not fear failure—they fear the negative evaluation associated with failure. A 50-50 chance of success causes maximum uncertainty and worry, and thus it increases the possibility of demonstrating low ability or competence. If low achievers cannot avoid such a situation, they become preoccupied and distraught because of their high need to avoid

failure.

Emotional Reactions

The fourth component of the need achievement theory is the individual’s emotional reactions, specifically how much pride and shame she experiences. Both high and low achievers want to experience pride and minimize shame, but their personality characteristics interact differently with the situation to cause them to focus more on either pride or shame. High achievers focus more on pride, whereas low achievers focus more on shame and worry.

Achievement Behavior

The fifth component of the need achievement theory indicates how the four other components interact to influence behavior. High achievers select more challenging tasks, prefer intermediate risks, and perform better in evaluative situations. Low achievers avoid intermediate risk, perform worse in evaluative situations, and avoid challenging tasks—by selecting tasks so difficult that they are certain to fail or tasks so easy that they are guaranteed success.

Significance of Need Achievement Theory

These performance predictions of the need achievement theory serve as the framework for all contemporary achievement motivation explanations. That is, even though more recent theories offer different explanations for the thought processes underlying achievement differences, the behavioral predictions between high and low achievers are basically the same. The most important contribution of need achievement

theory is its task preference and performance predictions.

Attribution Theory

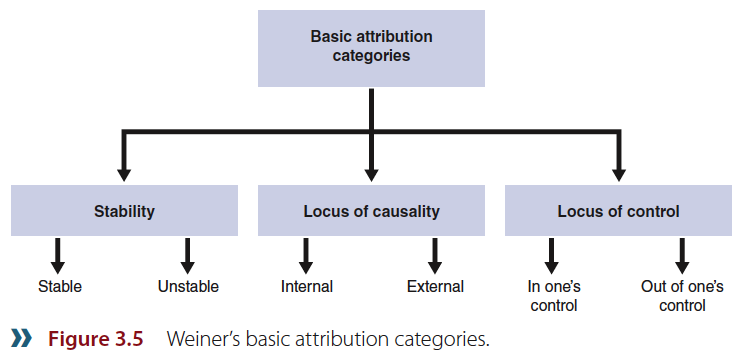

Attribution theory focuses on how people explain their successes and failures. This view, originated by Heider (1958) and extended and popularized by Weiner (1985, 1986), holds that literally thousands of possible explanations for success and failure can be classified into a few categories (see figure 3.5). These most basic attribution categories are stability (a factor to which one attributes success or failure is either fairly permanent or unstable), locus of causality (a factor is either external or internal to the individual), and locus of control (a factor is or is not under our control).

Attributions As Causes of Success and Failure

A performer can perceive his success or failure as attributable to a variety of possible reasons. These perceived causes of success or failure are called attributions. For example, you may win a swimming race and attribute your success to

Or you may drop out of an exercise program and attribute your failure to

Why Attributions Are Important

Attributions affect expectations of future success or failure and emotional reactions (Biddle, Hanrahan, & Sellars, 2001; McAuley, 1993b). Attributing performance to certain types of stable factors has been linked to expectations of future success. For example, if Susie, an elementary physical education student, ascribes her gymnastics performance success to a stable cause (e.g., her high ability), she will expect the outcome to occur again in the future and will be more motivated and confident. She may even ask her parents if she can sign up for after-school gymnastics. In contrast, if Zachary attributes his performance success in tumbling to an unstable cause (e.g., luck), he won’t expect it to occur regularly and his motivation and confidence will not be enhanced. He probably wouldn’t pursue after-school gymnastics. Of course, a failure also can be ascribed to a stable cause, such as low ability, which would lessen confidence and motivation, or to an unstable cause (e.g., luck), which would not.

Attributions to internal factors and to factors in our control (e.g., ability, effort) rather than to external factors or factors outside our control (e.g., luck, task difficulty) often result in emotional reactions like pride and shame. For example, a lacrosse player will experience more pride (if successful) or shame (if unsuccessful) if she attributes her performance to internal factors than she would if she attributes it to luck or an opponent’s skill (see table 3.1).

Achievement Goal Theory

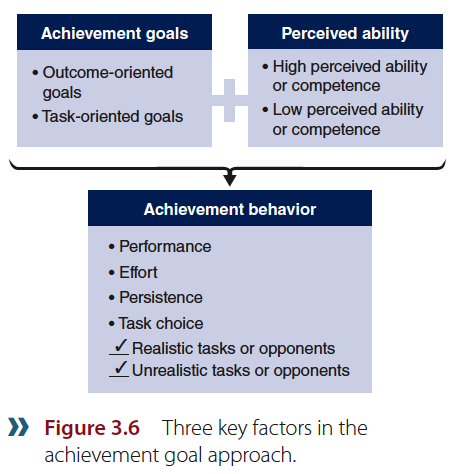

Both psychologists and sport and exercise psychologists have focused on achievement goals as a way of understanding differences in achievement (Duda & Hall, 2001; Dweck, 1986; Maehr & Nicholls, 1980; Nicholls, 1984; Roberts, 1993). According to the achievement goal theory, three factors interact to determine a person’s motivation: achievement goals, perceived ability, and achievement behavior (see figure 3.6). To understand someone’s motivation, we must understand what success and failure mean to that person. And the best way to do that is to examine a person’s achievement goals and how they interact with that individual’s perceptions of competence, self-worth, or perceived ability.

Outcome and Task Orientations

Holly may compete in bodybuilding because she wants to win trophies and have the best physique of anybody in the area. She has adopted an outcome goal orientation (also called a competitive goal orientation), in which the focus is on comparing herself with and defeating others. Holly feels good about herself (has high perceived ability) when she wins but not so good about herself (has low perceived ability) when she loses.

Sarah also likes to win contests, but she primarily takes part in bodybuilding to see how much she can improve her strength and physique. She has adopted a task goal orientation (also called a mastery goal orientation), in which the focus is on improving relative to her own past performances. Her perceived ability is not based on a comparison with others.

For a particular situation, some people can be both task and outcome oriented. For example, a person might want to win the local turkey trot but also to set a personal best time for the race. However, according to researchers in achievement goal orientation, most people tend to be higher on either task or outcome orientation.

Value of a Task Orientation

Sport psychologists argue that a task orientation more often than an outcome orientation leads to a strong work ethic, persistence in the face of failure, and optimal performance. This orientation can protect a person from disappointment, frustration, and a lack of motivation when the performance of others is superior (something that often cannot be controlled). Because focusing on personal performance provides greater control, individuals become more motivated and persist longer in the face of failure.

Task-oriented people also select moderately difficult or realistic tasks and opponents. They do not fear failure. And because their perception of ability is based on their own standards of reference, it is easier for them to feel good about themselves and to demonstrate high perceived competence than it is for outcome-oriented individuals.

Problems With Outcome Orientation

In contrast to task-oriented individuals, outcome-oriented people have more difficulty maintaining high perceived competence. They judge success by how they compare with others, but they cannot necessarily control how others perform. After all, at least half of the competitors must lose, which can lower a fragile perceived competence. People who are outcome oriented and have low perceived competence demonstrate a low or maladaptive achievement behavioral pattern (Duda & Hall, 2001). That is, they are likely to reduce their efforts, cease trying, or make excuses. To protect their self-worth they are more likely to select tasks in which they are guaranteed success or are so outmatched that no one would expect them to do well. They tend to perform less well in evaluative situations (see “Setting Outcome Goals and One Skier’s Downfall”).

Social Goal Orientations

Most goal orientation research has focused on task or outcome goal orientations. However, contemporary investigators have also identified social goal orientations as additional determinants of behavior (Allen, 2003; Stuntz & Weiss, 2003). Individuals high in a social goal orientation judge their competence in terms of affiliation with the group and recognition from being liked by others. Hence, in addition to judging their ability relative to their own and others’ performances, they would also be motivated by the desire for social connections and the need to belong to a group. Social goal orientations are important because they have been shown to be related to participant enjoyment, intrinsic motivation, and competence (Stuntz & Weiss, 2009). Thus, defining success in terms of social relationships has positive motivational effects.

Entity Versus Incremental Goal Perspectives

Elliott and Dweck (1988) proposed that, similar to task and outcome goals, achievement behavior patterns are explained by how participants view their ability. According to these researchers, participants who are characterized by an entity view adopt an outcome goal focus, where they see their ability as fixed and unable to be changed through effort, or an incremental focus, where they adopt a task goal perspective and believe they can change their ability through hard work and effort. Research shows that physical activity participants who adopt an entity focus are characterized by maladaptive motivation patterns (e.g., negative self-thoughts and feelings; Li & Lee, 2004).

![]()

Setting Outcome Goals and One Skier’s Downfall

After years of hard work, Dave becomes a member of the U.S. ski team. He has always set outcome goals for himself: becoming the fastest skier in his local club, winning regional races, beating arch-rivals, and placing at nationals. Unfortunately, he gets off to a rocky start on the World Cup circuit. He had wanted to be the fastest American downhiller and to place in the top three at each World Cup race, but with so many good racers competing it has become impossible to beat them consistently. To make matters worse, because of his lowered world ranking, Dave skis far back in the pack (after the course has been chopped up by the previous competitors), which makes it virtually impossible to place in the top three.

As Dave becomes more frustrated by his failures, his motivation declines. He no longer looks forward to competitions; he either skis out of control, focused entirely on finishing first, or skis such a safe line through the course that he finishes well back in the field. Dave blames his poor finishes on the wrong ski wax and equipment. He does not realize that his outcome goal orientation, which had served him well at the lower levels of competition where he could more easily win, is now leading to lower confidence, self-doubts, and less motivation.

Importance of Motivational Climate

In recent years, sport psychologists have studied not only how goal orientations and perceived ability work together to influence motivation of physical activity participants, but also how the social climate influences one’s goal orientations and motivation level (Duda, 2005; Ntoumanis & Biddle, 1999). Some psychologists contend, for example, that the social climates of achievement settings can vary significantly in several dimensions. These include such things as the tasks that learners are asked to perform, student–teacher authority patterns, recognition systems, student ability groupings, evaluation procedures, and times allotted for activities to be performed (Ames, 1992).

Research has revealed that in a motivational climate of mastery or task goal orientation, there are more adaptive motivational patterns, such as positive attitudes, increased effort, and effective learning strategies. In contrast, a motivational climate of outcome orientation has been linked with less adaptive motivational patterns, such as low persistence, low effort, and attribution of failures to (low) ability (Ntoumanis & Biddle, 1999).

Most important, researchers have found that motivational climates influence the types of achievement goals participants adopt: Task-oriented climates are associated with task goals and outcome-oriented climates with outcome goals (Duda & Hall, 2001). Coaches, teachers, and exercise leaders, then, play an important role in facilitating motivation through the psychological climates they create.

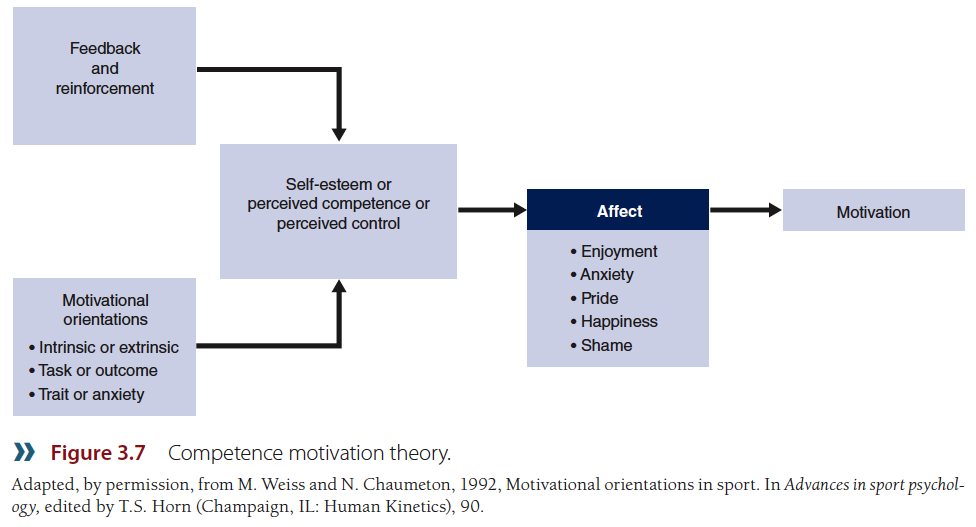

Competence Motivation Theory

A final theory that has been used to explain differences in achievement behavior, especially in children, is competence motivation theory (Weiss & Chaumeton, 1992). Based on the work of developmental psychologist Susan Harter (1988), this theory holds that people are motivated to feel worthy or competent and, moreover, that such feelings are the primary determinants of motivation (see figure 3.7). The competence motivation theory also contends that athletes’ perceptions of control (feeling control over whether they can learn and perform skills) work along with self-worth and competence evaluations to influence their motivation. However, these feelings do not influence motivation directly. Rather, they influence affective or emotional states (such as enjoyment, anxiety, pride, and shame) that in turn influence motivation.

If a young soccer player, for example, has high self-esteem, feels competent, and perceives that he has control over the learning and performance of soccer skills, then efforts to learn the game will increase his enjoyment, pride, and happiness. These positive affective states will in turn lead to increased motivation. In contrast, if an exerciser has low self-esteem, feels incompetent, and believes that personal actions have little bearing on increasing fitness, negative affective responses will result, such as anxiety, shame, and sadness. These feelings will lead to a decline in motivation.

Considerable research has demonstrated the link between competence and motivation (Weiss, 1993). The left side of the model (see figure 3.7) also shows that feedback and reinforcement from others and various motivational orientations (such as goal orientations and trait anxiety) influence feelings of self-esteem, competence, and control. Wong and Bridges (1995) tested this model using 108 youth soccer players and their coaches. The researchers measured perceived competence, perceived control, trait anxiety, and motivation as well as various coaching behaviors. As you might expect, they found that trait anxiety and coaching behaviors predicted perceived competence and control, which in turn were related to the players’ motivation levels. Hence, the perceptions of competence and control that young athletes have are critical determinants of whether they will strive toward achievement. Thus, enhancing perceived competence and control should be primary goals of professionals in exercise and sport science.

What Theories of Achievement Motivation Tell Us

To compare how these four theories explain achievement motivation, table 3.2 summarizes major predictions from each, showing how high and low achievers differ in terms of their motivational orientation and attributions, the goals they adopt, their task choices, their perceived competence and control, and their performance. We next discuss how a person’s achievement motivation and competitiveness develop.

Developing Achievement Motivation and Competitiveness

Is achievement motivation learned? At what age do children develop achievement tendencies? Can sport and exercise professionals influence and motivate children toward certain kinds of achievement?

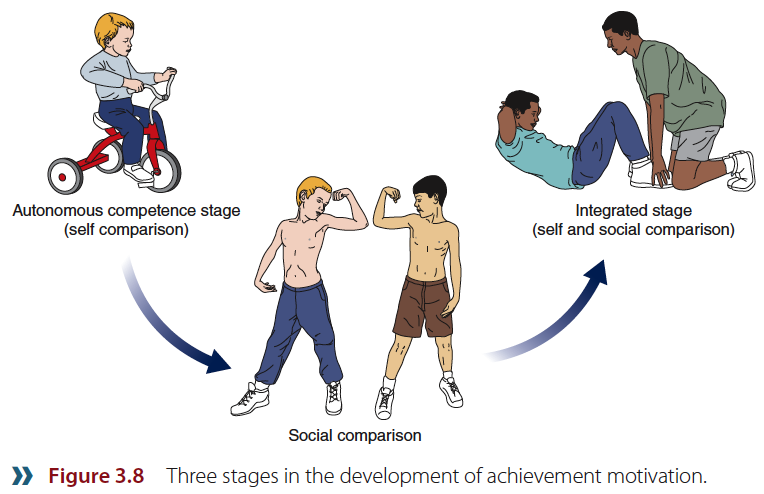

Achievement motivation and competitiveness are believed to develop in three stages (Scanlan, 1988; Veroff, 1969). These stages are sequential—that is, you must move through one stage before progressing to the next (see figure 3.8). Not everyone makes it to the final stage, and the age at which people reach each stage varies considerably. These are the three stages:

1. Autonomous competence stage. In this stage, which is thought to occur before the age of 4 years, children focus on mastering their environment and on self-testing. For example, Brandon is a preschooler who is highly motivated to learn to ride his tricycle, and he couldn’t care less that his sister Eileen can ride better than he can. He rarely compares himself with others.

2. Social comparison stage. In the social comparison stage, which begins at about the age of 5 years, a child focuses on directly comparing his performance with that of others, unlike what occurs in the autonomous stage with its self-referenced standards. Children seem preoccupied with comparing themselves to others, asking, “Who is faster, bigger, smarter, and stronger?”

3. Integrated stage. The integrated stage involves both social comparison and autonomous achievement strategies. The person who fully masters this integration knows when it is appropriate to compete and compare herself with others and when it is appropriate to adopt self-referenced standards. This stage, which integrates components from the previous two stages, is the most desirable. There is no typical age for entering this stage.

Importance of Distinguishing Between Stages

Recognizing the developmental stages of achievement motivation and competitiveness helps us to understand better the behavior of people we work with, especially children. Thus, we will not be surprised when a preschooler is not interested in competition or when fourth and fifth graders seem preoccupied with it. An integrated achievement orientation, however, must ultimately be developed, and it is important to teach children when it is appropriate or inappropriate to compete and compare themselves socially.

Tips for Guiding Achievement Orientation

Influencing Stages of Achievement Motivation

The social environment in which a person functions has important implications for achievement motivation and competitiveness. Significant others can play an important role in creating a positive or negative climate.

Parents, teachers, and coaches all play especially important roles. Teachers and coaches directly and indirectly create motivational climates. They define tasks and games as competitive or cooperative, group children in certain ways (e.g., picking teams through a public draft in which social comparison openly occurs), and differentially emphasize task or outcome goals (Ames, 1987; Roberts, 1993).

As professionals we can play significant roles in creating climates that enhance participant achievement motivation. For example, Treasure and Roberts (1995) created both task and outcome motivational climates in a youth soccer physical education class study. They found that after 10 sessions of having players participate in each climate, players who performed in the mastery climate focused more on effort, were more satisfied, and preferred more challenging tasks than outcome-climate participants. Similarly, Pensgaard and Roberts (2000) examined the relationship between motivational climate and stress in Olympic soccer players and found that a perception of a mastery climate was related to reduced stress. Hence, the motivational climate created by teachers and coaches influences achievement motivation and other important psychological states (stress).

Using Achievement Motivation in Professional Practice

Now that you better understand what achievement motivation and competitiveness involve and how they develop and influence psychological states, you can draw implications for professional practice. To help you consolidate your understanding, we now discuss some methods you can use to help people you work with.

Recognize Interactional Factors in Achievement Motivation

You know now that the interaction of personal and situational factors influences the motivation that particular students, athletes, and exercisers have to achieve. What should you watch for to guide your practice? Essentially, you assess

Let’s take two examples. Jose performs well in competition, seeks out challenges, sets mastery goals, and attributes success to stable internal factors such as his ability. These are desirable behaviors, and he is most likely a high achiever. You see, however, that Felix avoids competitors of equal ability, gravitates toward extreme competitive situations (where either success or failure is almost certain), focuses on outcome goals, becomes tense in competitions, and attributes failure to his low ability (or attributes success to external, unstable factors, such as luck). He demonstrates maladaptive achievement behavior, and he will need your help and guidance.

Felix’s may even be a case of learned helplessness, an acquired condition in which a person perceives that his or her actions have no effect on the desired outcome of a task or skill (Dweck, 1980). In other words, the person feels doomed to failure and believes that nothing can be done about it. The individual probably makes unhelpful attributions for failure and feels generally incompetent (see “Recognizing a Case of Learned Helplessness”).

![]()

Recognizing a Case of Learned Helplessness

Johnny is a fifth grader in Ms. Roalston’s second-period physical education class. He is not a very gifted student, but he can improve with consistent effort. However, after observing and getting to know Johnny, Ms. Roalston has become increasingly concerned. He demonstrates many of the characteristics of learned helplessness that she became familiar with in her university sport psychology and sport pedagogy

classes.

Johnny has all the characteristics of learned helplessness. Ms. Roalston remembers that learned helplessness is not a personality flaw—it is not Johnny’s fault. Rather, it results from an outcome goal orientation; maladaptive achievement tendencies; previous negative experiences with physical activity; and attributions of performance to uncontrollable, stable factors, especially low ability. Equally important, learned helplessness can vary in its specificity—it can be specific to a particular activity (e.g., learning to catch a baseball) or can be more general (e.g., learning any sport skill). Ms. Roalston knows that learned helplessness can be overcome by giving Johnny some individual attention, repeatedly emphasizing mastery goals, and downplaying outcome goals. Attributional retraining or getting Johnny to change his low-ability attributions for failure will also help him. It will take some time and hard work, but she decides that a major goal for the year is to help get Johnny out of his helpless hole.

Emphasize Task Goals

There are several ways to help prevent maladaptive achievement tendencies or rectify learned helpless states. One of the most important strategies is to help people set task goals and downplay outcome goals. Society emphasizes athletic outcomes and student grades so much that downplaying outcome goals is not always easy. Luckily, however, sport and exercise psychologists have learned a great deal about goal setting (see more in chapter 15).

Monitor and Alter Attributional Feedback

In addition to downplaying outcome goals and emphasizing task or individual-specific mastery goals, you must be conscious of the attributions you make while giving feedback. It is not unusual for teachers, coaches, or exercise leaders to unknowingly convey subtle but powerful messages through the attributions that accompany their feedback. Adults influence a child’s interpretations of performance success—and future motivation—by how they give feedback (Biddle et al., 2001; Horn, 1987). For example, notice how this physical educator provides feedback to a child in a volleyball instructional setting:

You did not bump the ball correctly. Bend your knees more and contact the ball with your forearms. Try harder—you’ll get it with practice.

The coach not only conveys instructional information to the young athlete but also informs the child that he can accomplish the task. The instructor also concludes the message by stating that persistence and effort pay off. In contrast, consider the effects of telling that same child the following:

You did not bump the ball correctly! Your knees were not bent and you did not use your forearms. Don’t worry, though—I know softball is your game, not volleyball.

Although well-meaning, this message informs the young athlete that she will not be good at volleyball, so she shouldn’t bother trying. Of course you should not make unrealistic attributions (e.g., telling an exerciser that with continued work and effort she will look like a model when in fact her body type makes this unlikely). Rather, the key is to emphasize mastery goals by focusing on individual improvement and then to link attributions to those individual goals (e.g., “I’ll be honest. You’ll never have a body like Tyra Banks, but with hard work you can look and feel a lot better than you do now”).

When you work with children, attributing performance failure to their low effort may be effective only if they believe they have the skills they need to ultimately achieve the task (Horn, 1987). If Jimmy believes that he is totally inept at basketball, telling him that he didn’t learn to dribble because he did not try will not increase his achievement motivation—it may only reinforce his low perception of ability. Do not make low-effort attributions with children under the age of 9 unless you also reassure them that they have the skills to accomplish the task. The child must believe he has the skills to perform the

task.

Assess and Correct Inappropriate Attributions

We need to monitor and correct inappropriate or maladaptive attributions that participants make of themselves. Many performers who fail (especially those with learned helplessness) attribute their failure to low ability, saying things like “I stink” or “Why even try? I just don’t have it.” They definitely adopt an entity perspective to defining ability. Teaching children in classroom situations to replace their lack-of-ability attributions with lack-of-effort attributions helped them alleviate performance decrements after failure—this strategy was more effective even than actual success (Dweck, 1975)! Moreover, attribution retraining focusing on creating positive emotional states and expectations after success, and especially avoiding low-ability attributions after failure, has been shown to be effective in sport and physical education contexts (Biddle et al., 2001). If you hear students or clients make incorrect attributions for successful performances, such as “That was a lucky shot,” correct them and indicate that hard work and practice made the shot successful, not luck. Especially important is the need to correct participants when they make low-ability attributions after failure (get them to change from statements like “I stink, why even try? I will never get it” to “I’ll get it if I just hang in there and focus on what my coach said to do”). You have an important responsibility to ensure that participants use attributions that will facilitate achievement motivation and efforts.

Determine When Competitive Goals Are Appropriate

You are also responsible for helping participants determine when it is appropriate to compete and when it is appropriate to focus on individual improvement. Competing is sometimes a necessity in society (e.g., to make an athletic team or to gain admission to a selective college). At times, however, competing against others is counterproductive. You wouldn’t encourage a basketball player to not pass off to teammates who have better shots or a cardiac rehabilitation patient to exceed the safe training zone in order to be the fastest jogger in the group.

The key, then, is developing judgment. Through discussion you can help students, athletes, and exercisers make good decisions in this area. Society emphasizes social evaluation and competitive outcomes so much that you will need to counterbalance by stressing a task (as compared with an outcome) orientation (see chapter 3 for additional guidelines). Talking to someone once or twice about this issue is not enough: Consistent, repeated efforts are necessary to promote good judgment about appropriate competition.

Attributional Guidelines for Providing Instructor Feedback

Do

Don’t

Adapted from American College of Sports Medicine, 1997, ACSM’s health/fitness facility standards and guidelines, 2nd ed. (Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics).

Enhance Feelings of Competence and Control

Enhancing perceived competence and enhancing feelings of control are critical ways to foster achievement motivation in physical activity participants, especially children (Weiss, 1993). You can do this by keeping practices and competitions fun as well as achievement focused and by matching participant skills and abilities. Instructors can enhance competence by using appropriate feedback and reinforcement and by helping create individualized challenges and goals for participation (see chapters 6 and 15, respectively). Maximizing the involvement of all participants is critical for enhancing competence. You can find additional means of enhancing competence in chapter 14.

Learning Aids

Summary

1. Define motivation and its components.

Motivation can be defined as the direction and intensity of effort. The direction of effort refers to whether an individual seeks out, approaches, or is attracted to certain situations. The intensity of effort refers to how much effort a person puts forth in a particular situation.

2. Describe typical views of motivation and whether they are useful.

Three views of motivation include the trait-centered view, the situation-centered view, and the interactional view. Among these models of motivation, the participant-by-situation interactional view is the most useful for guiding professional practice.

3. Detail useful guidelines for building motivation.

Five fundamental observations, derived from the interactional view of motivation, make good guidelines for practice. First, participants are motivated both by their internal traits and by situations; second, it is important to understand their motives for involvement. Third, you should structure situations to meet the needs of participants. Fourth, recognize that as a teacher, coach, or exercise leader you play a critical role in the motivational environment; fifth, use behavior modification to change undesirable participant motives. Furthermore, you must also develop a realistic view of motivation: Recognize that other, nonmotivational factors influence sport performance and behavior and learn to assess whether motivational factors may be readily changed.

4. Define achievement motivation and competitiveness and indicate why they are important.

Achievement motivation refers to a person’s efforts to master a task, achieve excellence, overcome obstacles, perform better than others, and take pride in exercising talent. Competitiveness is a disposition to strive for satisfaction when making comparisons with some standard of excellence in the presence of evaluative others. These notions are important because they help us understand why some people seem so motivated to achieve and others seem simply to “go along for the ride.”

5. Compare and contrast theories of achievement motivation.

Theories of achievement motivation include the (a) need achievement theory, (b) attribution theory, (c) achievement goal theory, and (d) competence motivation theory. Together these theories suggest that high and low achievers can be distinguished by their motives, the tasks they select to be evaluated on, the effort they exert during competition, their persistence, and their performance. High achievers usually adopt mastery (task) goals and have high perceptions of their ability and control. They attribute successes to stable and internal factors like high ability; they attribute failure to unstable, controllable factors like low effort. Low achievers, on the other hand, usually have low perceived ability and control, judge themselves more on outcome goals, and attribute successes to luck or ease of the task (external, uncontrollable factors); they attribute failure to low ability (an internal, stable

attribute).

6. Explain how achievement motivation develops.

Achievement motivation and its sport-specific counterpart, competitiveness, develop through stages that include (a) an autonomous stage when the individual focuses on mastery of her environment, (b) a social comparison stage when the individual compares herself with others, and (c) an integrated stage when the individual both focuses on self-improvement and uses social comparison. The goal is for the individual to reach an autonomous, integrated stage and to know when it is appropriate to compete and compare socially and when instead to adopt a self-referenced focus of comparison.

7. Use fundamentals of achievement motivation to guide practice.

Parents, teachers, and coaches significantly influence the achievement motivation of children and can create climates that enhance achievement and counteract learned helplessness. They can best do this by (a) recognizing interactional influences on achievement motivation, (b) emphasizing individual task goals and downplaying outcome goals, (c) monitoring and providing appropriate attributional feedback, (d) teaching participants to make appropriate attributions, (e) discussing with participants when it is appropriate to compete and compare themselves socially and when it is appropriate to adopt a self-referenced focus, and (f) facilitating perceptions of competence and control.

Key Terms

motivation

direction of effort

intensity of effort

trait-centered view (participant-centered view)

situation-centered view

interactional view

achievement motivation

competitiveness

need achievement theory

probability of success

incentive value of success

resultant tendency (behavioral tendency)

attribution theory

stability

locus of causality

locus of control

achievement goal theory

outcome goal orientation (competitive goal orientation)

task goal orientation (mastery goal orientation)

entity view

incremental focus

competence motivation theory

learned helplessness

Review Questions

1. Explain the direction and intensity aspects of motivation.

2. Identify three general views of motivation. Which should be used to guide practice?

3. How does the swimming relay study (by Sorrentino and Sheppard) support the interactional model of motivation?

4. Describe five fundamental guidelines of motivation for professional practice.

5. What are the primary motives people have for participating in sport? What are their primary motives for participating in exercise activities?

6. When is it appropriate to use behavior modification techniques to alter motivation for sport and exercise involvement?

7. What major factors besides motivation should you consider in order to understand performance and behavior in exercise and sport settings?

8. Give examples of motivational factors that are readily influenced.

9. What is the difference between achievement motivation and competitiveness?

10. In what ways does achievement motivation influence participant behavior?

11. Explain and distinguish four theories to explain achievement motivation.

12. How do high and low achievers differ in the types of challenges and tasks they select?

13. What are attributions? Why are they important in helping us understand achievement motivation in sport and exercise settings?

14. Distinguish between an outcome (competitive) and a task (mastery) goal orientation. Which should be most emphasized in sport, physical education, and exercise settings? Why?

15. Identify the three stages of achievement motivation and competitiveness. Why are these important?

16. Discuss how a teacher’s or coach’s attributional feedback influences participant achievement. What are the key components of attributional retraining?

17. What is learned helplessness? Why is it important?

Critical Thinking Questions

1. List at least three ways to better understand someone’s motives for sport and physical activity involvement.

2. Design a program to eliminate learned helplessness in performers. Indicate how you will foster an appropriate motivational climate.