After reading this chapter, you should be able to

1. define and understand the benefits of self-confidence,

2. discuss the sources of sport confidence,

3. understand how expectations affect performance and behavior,

4. explain the theory of self-efficacy,

5. explain how you would assess self-confidence,

6. explain the various aspects of coaching efficacy, and

7. describe strategies for building self-confidence.

During interviews following competitions, athletes and coaches inevitably discuss the critical role that self-confidence (or a lack of self-confidence) played in their mental success (or failure). For example, Trevor Hoffman, one of the top “closers” pitching in the major leagues, has stated, “Confidence is everything; if you start second guessing yourself, you’re bound to run into more bad outings.” Or, as Tiger Woods has noted, “The biggest thing is to have the belief that you can win every tournament going in. A lot of guys don’t have that. Jack Nicklaus did.” Great athletes also keep their confidence high despite poor recent performance. For example, New York Yankee star shortstop Derek Jeter stated that even in the midst of a slump (which he had in the 2004 season and recovered to have an excellent year), “I never lose my confidence. It doesn’t mean I’m going to get hits, but I have my confidence all the time” (McCallum & Verducci, 2004). Finally, sometimes confidence is felt not only by athletes but by their competitors. For example, at the end of 2004, Andy Roddick talked about Roger Federer (winner of several Grand Slam titles and predicted to win many more). “He’s got an aura about him in the locker room. Mentally, he’s so confident right now. A lot of his success right now is between the ears.” These comments by Roddick are echoed by Federer himself, who has said, “I believe strongly in my capabilities. There’s a lot of confidence as well, with my record over the past few years. I’ve built up this feeling on big points that I can do it over and over again. Things are now just coming automatically.” (This is bad news for other men’s professional tennis players, because Federer won 22 consecutive finals in which he played, until he finally lost a 5 setter to David Nalbandian.)

Research, too, indicates that the factor most consistently distinguishing highly successful from less successful athletes is confidence (Jones & Hardy, 1990; Vealey, 2005). In addition, Gould, Greenleaf, Lauer, and Chung (1999) found that confidence (efficacy) was among the chief factors influencing performance at the Nagano Olympic Games. Along these lines, in interviews with 63 of the highest achievers from a wide variety of sports, nearly 90% stated that they had a very high level of self-confidence. Top athletes, regardless of the sport, consistently display a strong belief in themselves and their abilities. Let’s look at how Olympic decathlon gold medalist Daly Thompson and all-time tennis great Jimmy Connors view confidence.

I’ve always been confident of doing well. I know whether or not I’m going to win. I have doubts, but come a week or ten days before the event, they’re all gone. I’ve never gone into competition with any doubts. I’ve always had confidence of putting 100% in and at the end of the day, I think regardless of where you come out, you can’t do any more than try your best.

—Daly Thompson (cited in Hemery, 1986, p. 156)

The whole thing is never to get negative about yourself. Sure, it’s possible that the other guy you’re playing is tough and that he may have beaten you the last time you played, and okay, maybe you haven’t been playing all that well yourself. But the minute you start thinking about these things you’re dead. I go out to every match convinced that I’m going to win. That’s all there is to it.

—Jimmy Connors (cited in Weinberg, 1988, p. 127)

Even elite athletes sometimes have self-doubts, however, although they still seem to hold the belief that they can perform at high levels. Former world-class middle-distance runner Herb Elliott stated, “I think one of my big strengths has been my doubts of myself; if you’re very aware of the weaknesses and are full of your own self-doubts, in a sense, that’s quite a motivation.” Similarly, former elite middle-distance runner Steve Ovett stated, “There’s always a worry that I’d never live up to the expectations of my friends” (Hemery, 1986, p. 155). Finally, even basketball legend Michael Jordan speaks of gaining confidence through failure, as the following quote suggests:

I’ve missed more than 9,000 shots in my career. I’ve lost almost 300 games. Twenty-six times I’ve been trusted to take the game winning shot and missed. I’ve failed over and over and over again in my life—and that is why I succeed.

So sometimes there is a struggle between feeling self-confident and recognizing your weaknesses. Let’s begin by defining what we mean by self-confidence.

DEFINING SELF-CONFIDENCE

Although we hear athletes and exercisers talk about confidence all the time, it is not an easy term to define. Sport psychologists define self-confidence as the belief that you can successfully perform a desired behavior. The desired behavior might be kicking a soccer goal, staying in an exercise regimen, recovering from a knee injury, serving an ace, or hitting a home run. But the common factor is that you believe you will get the job done.

Although Vealey (1986) originally viewed self-confidence as both a disposition and a state, the latest thinking (Vealey, 2001) is that sport self-confidence is a social cognitive construct that can be more traitlike or more statelike, depending on the temporal frame of reference used. For example, confidence could differ if we look at confidence about today’s competition versus confidence about the upcoming season versus one’s typical level of confidence. In essence, confidence might be something you feel today and therefore it might be unstable (state self-confidence), or it might be part of your personality and thus be very stable (trait self-confidence). Another recent development is the view that confidence is affected by the specific organizational culture as well as the general sociocultural forces surrounding sport and exercise. For instance, an exerciser may get lots of positive feedback from the instructor, which helps to build his confidence, in contrast to no feedback (or even negative comments), which might undermine confidence. In sport, participation in certain activities is seen as more appropriate for males (e.g., wrestling) or females (e.g., figure skating), and this would certainly affect an athlete’s feelings of confidence. Here is how a college basketball player described self-confidence and its sometimes transient nature:

The whole thing is to have a positive mental approach. As a shooter, you know that you will probably miss at least 50% of your shots. So you can’t get down on yourself just because you miss a few in a row. Still, I know it’s easy for me to lose my confidence fast. Therefore, when I do miss several shots in a row I try to think that I am more likely to make the next one since I’m a 50% shooter. If I feel confident in myself and my abilities, then everything else seems to fall into place.

When you expect something to go wrong, you are creating what is called a self-fulfilling prophecy, which means that expecting something to happen actually helps cause it to happen. Unfortunately, this phenomenon is common in both competitive sport and exercise programs. Negative self-fulfilling prophecies are psychological barriers that lead to a vicious cycle: The expectation of failure leads to actual failure, which lowers self-image and increases expectations of future failure. For example, a baseball batter in a slump begins to expect to strike out, which leads to increased anxiety and decreased concentration, which in turn usually result in lowered expectancies and poorer performance.

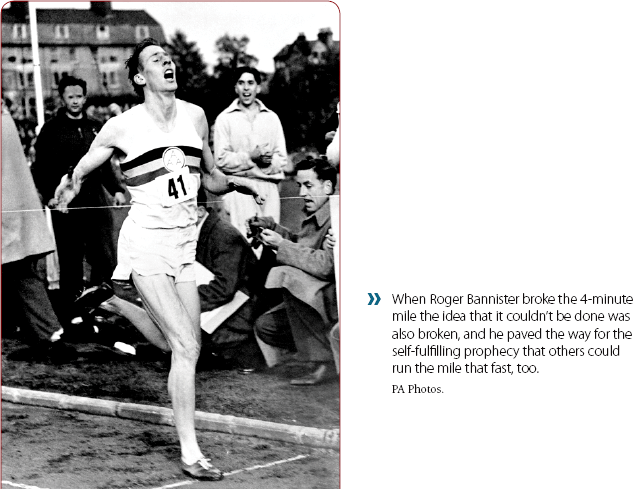

A great example of someone’s overcoming a negative self-fulfilling prophecy is the story of how Roger Bannister broke the 4-minute mile. Before 1954, most people claimed there was no way to run a mile in less than 4 minutes. Many runners were timed at 4:03, 4:02, and 4:01, but most runners agreed that to get below 4 minutes was physiologically impossible. Roger Bannister, however, did not. Bannister believed that he could break the 4-minute barrier under the right conditions—and he did. Bannister’s feat was impressive, but what’s really interesting is that in the next year more than a dozen runners broke the 4-minute mile. Why? Did everyone suddenly get faster or start training harder? Of course not. What happened was that runners finally believed it could be done. Until Roger Bannister broke the barrier, runners had been placing psychological limits on themselves because they believed it just wasn’t possible to break the 4-minute mile.

Research (Vealey & Knight, 2002) has revealed that like many other current personality constructs, self-confidence may be multidimensional, consisting of several aspects. Specifically, there appear to be several types of self-confidence within sport, including the following:

Confidence about one’s ability to execute physical skills

Confidence about one’s ability to execute physical skills

Confidence about one’s ability to use psychological skills (e.g., imagery, self-talk)

Confidence about one’s ability to use psychological skills (e.g., imagery, self-talk)

Confidence to use perceptual skills (e.g., decision making, adaptability)

Confidence to use perceptual skills (e.g., decision making, adaptability)

Confidence in one’s level of physical fitness and training status

Confidence in one’s level of physical fitness and training status

Confidence in one’s learning potential or ability to improve one’s skill

Confidence in one’s learning potential or ability to improve one’s skill

More recently, Hays, Maynard, Thomas, and Bawden (2007) assessed types of self-confidence in elite performers and found additional types such as belief in their ability to achieve (both winning and improved performance) as well as their belief in their superiority over the opposition. This underscores the notion of elite athletes having strong beliefs in their abilities and is consistent with the importance of self-belief as seen in the mental toughness literature.

Benefits of Self-Confidence

Self-confidence is characterized by a high expectancy of success. It can help individuals to arouse positive emotions, facilitate concentration, set goals, increase effort, focus their game strategies, and maintain momentum. In essence, confidence can influence affect, behavior, and cognitions (the ABCs of sport psychology). We’ll discuss each of these briefly.

Confidence arouses positive emotions. When you feel confident, you are more likely to remain calm and relaxed under pressure. This state of mind and body allows you to be aggressive and assertive when the outcome of the competition lies in the balance. In addition, research (Jones & Swain, 1995) has revealed that athletes with high confidence interpret their anxiety levels more positively than do those with less confidence. This provides a more productive belief system in which one can reframe emotions as facilitative to performance.

Confidence arouses positive emotions. When you feel confident, you are more likely to remain calm and relaxed under pressure. This state of mind and body allows you to be aggressive and assertive when the outcome of the competition lies in the balance. In addition, research (Jones & Swain, 1995) has revealed that athletes with high confidence interpret their anxiety levels more positively than do those with less confidence. This provides a more productive belief system in which one can reframe emotions as facilitative to performance.

Confidence facilitates concentration. When you feel confident, your mind is free to focus on the task at hand. When you lack confidence, you tend to worry about how well you are doing or how well others think you are doing. In essence, confident individuals are more skillful and efficient in using cognitive processes and have more productive attentional skills, attributional patterns, and coping strategies.

Confidence facilitates concentration. When you feel confident, your mind is free to focus on the task at hand. When you lack confidence, you tend to worry about how well you are doing or how well others think you are doing. In essence, confident individuals are more skillful and efficient in using cognitive processes and have more productive attentional skills, attributional patterns, and coping strategies.

Confidence affects goals. Confident people tend to set challenging goals and pursue them actively. Confidence allows you to reach for the stars and realize your potential. People who are not confident tend to set easy goals and never push themselves to the limits (see goal setting in chapter 15).

Confidence affects goals. Confident people tend to set challenging goals and pursue them actively. Confidence allows you to reach for the stars and realize your potential. People who are not confident tend to set easy goals and never push themselves to the limits (see goal setting in chapter 15).

Confidence increases effort. How much effort someone expends and how long the individual will persist in pursuit of a goal depend largely on confidence (Weinberg, Yukelson, & Jackson, 1980). When ability is equal, the winners of competitions are usually the athletes who believe in themselves and their abilities. This is especially true in situations that necessitate persistence (as in running a marathon or playing a 3-hour tennis match) or in the face of obstacles such as painful rehabilitation sessions (Maddux & Lewis, 1995).

Confidence increases effort. How much effort someone expends and how long the individual will persist in pursuit of a goal depend largely on confidence (Weinberg, Yukelson, & Jackson, 1980). When ability is equal, the winners of competitions are usually the athletes who believe in themselves and their abilities. This is especially true in situations that necessitate persistence (as in running a marathon or playing a 3-hour tennis match) or in the face of obstacles such as painful rehabilitation sessions (Maddux & Lewis, 1995).

Confidence affects game strategies. People in sport commonly refer to “playing to win” or, conversely, “playing not to lose.” Confident athletes tend to play to win: They are usually not afraid to take chances, and so they take control of the competition to their advantage. When athletes are not confident, they often play not to lose: They are tentative and try to avoid making mistakes. For example, a confident basketball player who comes off the bench will try to make things happen by scoring, stealing a pass, or getting an important rebound. A less confident player will try to avoid making a mistake, like turning over the ball. Players with less confidence are content not to mess up and are less concerned with making something positive happen.

Confidence affects game strategies. People in sport commonly refer to “playing to win” or, conversely, “playing not to lose.” Confident athletes tend to play to win: They are usually not afraid to take chances, and so they take control of the competition to their advantage. When athletes are not confident, they often play not to lose: They are tentative and try to avoid making mistakes. For example, a confident basketball player who comes off the bench will try to make things happen by scoring, stealing a pass, or getting an important rebound. A less confident player will try to avoid making a mistake, like turning over the ball. Players with less confidence are content not to mess up and are less concerned with making something positive happen.

Confidence affects psychological momentum. Athletes and coaches refer to momentum shifts as critical determinants of winning and losing (Miller & Weinberg, 1991). Being able to produce positive momentum or reverse negative momentum is an important asset. Confidence appears to be a critical ingredient in this process. People who are confident in themselves and their abilities never give up. They view situations in which things are going against them as challenges and react with increased determination. For example, Wayne Gretzky, Lebron James, Serena Williams, and Tiger Woods have exuded confidence to reverse momentum when the outlook looked bleak.

Confidence affects psychological momentum. Athletes and coaches refer to momentum shifts as critical determinants of winning and losing (Miller & Weinberg, 1991). Being able to produce positive momentum or reverse negative momentum is an important asset. Confidence appears to be a critical ingredient in this process. People who are confident in themselves and their abilities never give up. They view situations in which things are going against them as challenges and react with increased determination. For example, Wayne Gretzky, Lebron James, Serena Williams, and Tiger Woods have exuded confidence to reverse momentum when the outlook looked bleak.

Confidence affects performance. Probably the most important relationship for practitioners is the one between confidence and performance. Although we know from past research that there is a positive relationship between confidence and performance (Feltz, 1984b; Vealey, 2001), the factors affecting this relationship are less well known. However, such factors as organizational culture (e.g., high school vs. collegiate expectations), personality characteristics (e.g., competitive orientation), demographic characteristics (e.g., gender, age), affect (e.g., arousal or anxiety), and cognitions (e.g., attributions for success or failure) have been suggested to be important. All these factors affect whether confidence is too low, too high, or just right, as we briefly discuss in the following sections.

Optimal Self-Confidence

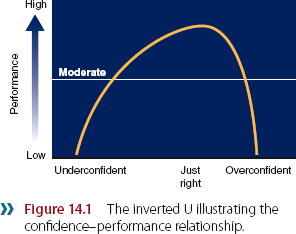

Although confidence is a critical determinant of performance, it will not overcome incompetence. Confidence can take an athlete only so far. The relation between confidence and performance can be represented by the form of an inverted U with the highest point skewed to the right (see figure 14.1). Performance improves as the level of confidence increases—up to an optimal point, whereupon further increases in confidence produce corresponding decrements in performance. Optimal self-confidence means being so convinced that you can achieve your goals that you will strive hard to do so. It does not necessarily mean that you will always perform well, but it is essential to reaching your potential. A strong belief in yourself will help you deal with errors and mistakes effectively and keep you striving toward success. Each person has an optimal level of self-confidence, and performance problems can arise with either too little or too much confidence.

Lack of Confidence

Many people have the physical skills to be successful but lack confidence in their ability to perform these skills under pressure—when the game or match is on the line. For example, a volleyball player consistently hits strong and accurate spikes during practice. In the match, however, her first spike is blocked back in her face. She starts to doubt herself and becomes tentative and conservative in subsequent spikes, thus losing her effectiveness.

Psychological Momentum: Illusion or Reality?

Most coaches and athletes speak about the concept of psychological momentum and how it is often elusive—one minute you have it, and the next minute you don’t. Researchers have sometimes found that this feeling of momentum might be more an illusion than a reality. For example, one study addressed the hot hand phenomenon in basketball, which traditionally has meant that when a player has hit a few shots in a row, he is likely to continue making baskets. Using records from professional basketball teams, researchers discovered that a player was just as likely to miss the next basket as to make the next basket after having made several successful shots in a row (Gillovich, Vallone, & Tversky, 1985; Koehler & Conley, 2003).

Other researchers also found that having momentum did not affect subsequent performance in baseball and volleyball (Albright, 1993; Miller & Weinberg, 1991, respectively). However, additional research has shown a relationship between psychological momentum and performance in sports such as tennis, basketball, and cycling (Jackson & Mosurki, 1997; Mace, Lalli, Shea, & Nevin, 1992; Perreault, Vallerand, Montgomery, & Provencher, 1998). It has been hypothesized that psychological momentum affects performance through cognitive (increased attention and confidence), affective (changes in perceptions of anxiety), and physiological (increased arousal) mechanisms (Taylor & Demick, 1994). Although there is some support for these notions (Kerick, Iso-Ahola, & Hatfield, 2000), further research is necessary to more clearly elucidate these intervening mechanisms. So the jury is still out on whether psychological momentum is real or simply an illusion. In fact, in a thorough review of 20 years of “hot hand” research, Bar-Eli, Avugos, and Raab (2006) conclude that although there is evidence against the existence of psychological momentum in basketball and a few other sports, simulations do lend some support to the presence of psychological momentum. However, Gula and Raab (2004) offered a sort of compromise position. Specifically, they argued that it would be best for a coach to select the player with the “hot hand” to shoot the last shot, but only if this player has a high base rate of success (e.g., is a good shooter to begin with). Thus, they perceive the “hot hand” as neither myth nor reality but rather as information to use when selecting a shooter for a critical situation.

Adding to the research on psychological momentum was a recent study investigating the strategies for maintaining positive momentum or overcoming negative momentum from players’ perspectives. Although self-confidence appeared to be the key factor regarding psychological momentum, other strategies were noted. These were sometimes similar and sometimes dissimilar for positive and negative momentum. For example, to develop or maintain psychological momentum, team and individual strategies included encouragement (e.g., coaches, teammates, spectators), targeting opponents’ weaknesses, maintaining concentration, controlling the pace of the game, changing tactics, and mental and physical preparation. Team and individual strategies to overcome negative momentum were encouragement (teammates, coaches, spectators), managing anxiety, controlling pace, and frustrating opponents.

Self-doubts undermine performance: They create anxiety, break concentration, and cause indecisiveness. Individuals lacking confidence focus on their shortcomings rather than on their strengths, distracting themselves from concentrating on the task at hand. Sometimes athletes in the training room doubt their ability to fully recover from injury. Exercisers often have self-doubts about the way they look or about their ability to stay with a regular exercise program. But, as noted earlier, for some individuals, a little self-doubt helps maintain motivation and prevents complacency or overconfidence.

Overconfidence

Overconfident people are actually falsely confident. That is, their confidence is greater than their abilities warrant. Their performance declines because they believe that they don’t have to prepare themselves or exert effort to get the job done. This occurs when a top-rated team takes another team for granted, its members thinking that all they have to do is show up to win. You cannot be overconfident, however, if your confidence is based on actual skill and ability. As a general rule, overconfidence is much less a problem than underconfidence. When overconfidence does occur, however, the results can be just as disastrous. In the mid-1970s, Bobby Riggs lost a famous “battle of the sexes” tennis match against Billie Jean King. Riggs explained the loss this way:

It was mainly a case of overconfidence on my part. I overestimated myself. I underestimated Billie Jean’s ability to meet the pressure. I let her pick the surface and the ball because I figured it wouldn’t make a difference, that she would beat herself. Even when she won the first set, I wasn’t worried. In fact, I tried to bet more money on myself. I miscalculated. I ran out of gas. She started playing better and better. I started playing worse. I tried to slow up the game to keep her back but she kept the pressure on. (Tarshis, 1977, p. 48)

More common is the situation in which two athletes or teams of different abilities play each other. The better player or team often approaches the competition overconfidently. The superior players slight preparation and perform haphazardly, which may well cause them to fall behind early in the competition. The opponent, meanwhile, starts to gain confidence, making it even harder for the overconfident players to come back and win. Another situation that most of us have seen is that of an athlete who is faking overconfidence. Often athletes do this in an attempt to please others and to hide actual feelings of self-doubt. It would be more constructive for athletes to express such feelings to the coach, so the coach can then devise programs to help athletes remove their doubts and gain back their self-confidence.

Sport Confidence Model

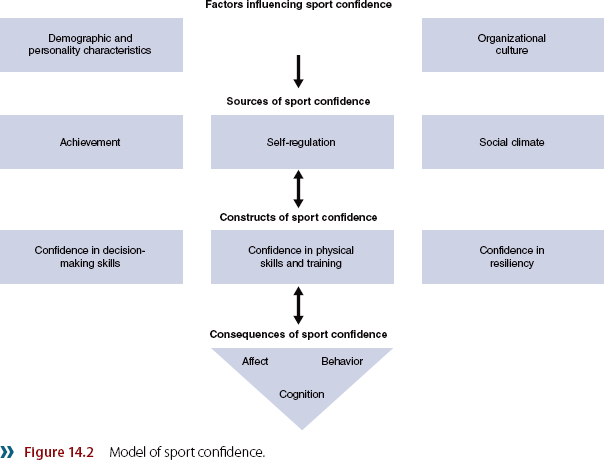

Now that we’ve discussed different aspects of sport self-confidence, it is time to put things together in a model of sport confidence (see figure 14.2) described by Vealey and her colleagues (Vealey 1986, 2001; Vealey, Hayashi, Garner-Holman, & Giacobbi, 1998). The sport confidence model has four components:

Constructs of sport confidence. As noted earlier in the chapter, sport confidence is seen as varying on a continuum from more traitlike to more statelike, as opposed to either purely trait or state self-confidence. Along these lines, self-confidence is defined as the belief or degree of certainty that individuals possess about their ability to be successful in sport. Furthermore, sport confidence is conceptualized as multidimensional, including confidence about physical ability, psychological and perceptual skills, adaptability, fitness and training level, learning potential, and decision making.

Constructs of sport confidence. As noted earlier in the chapter, sport confidence is seen as varying on a continuum from more traitlike to more statelike, as opposed to either purely trait or state self-confidence. Along these lines, self-confidence is defined as the belief or degree of certainty that individuals possess about their ability to be successful in sport. Furthermore, sport confidence is conceptualized as multidimensional, including confidence about physical ability, psychological and perceptual skills, adaptability, fitness and training level, learning potential, and decision making.

Sources of sport confidence. As described in “Sources of Sport Self-Confidence” on page 333, a number of sources are hypothesized to underlie and affect sport self-confidence. These can be further categorized as focusing on achievement, self-regulation, and social climate.

Sources of sport confidence. As described in “Sources of Sport Self-Confidence” on page 333, a number of sources are hypothesized to underlie and affect sport self-confidence. These can be further categorized as focusing on achievement, self-regulation, and social climate.

Consequences of sport confidence. These consequences refer to athletes’ affect (A), behavior (B), and cognitions (C), which Vealey (2001) labeled the ABC triangle. It is hypothesized that athletes’ level of sport confidence would continuously interplay with these three elements. In general, high levels of confidence arouse positive emotions, are linked to productive achievement behaviors such as effort and persistence, and produce more skilled and efficient use of cognitive resources such as attributional patterns, attentional skills, and coping strategies.

Consequences of sport confidence. These consequences refer to athletes’ affect (A), behavior (B), and cognitions (C), which Vealey (2001) labeled the ABC triangle. It is hypothesized that athletes’ level of sport confidence would continuously interplay with these three elements. In general, high levels of confidence arouse positive emotions, are linked to productive achievement behaviors such as effort and persistence, and produce more skilled and efficient use of cognitive resources such as attributional patterns, attentional skills, and coping strategies.

Factors influencing sport confidence. It is hypothesized that organizational culture as well as demographic and personality characteristics influence sport confidence. Organizational culture represents the structural and cultural aspects of the sport subculture, which can include such things as level of competition, motivational climate, coaching behaviors, and expectations of different sport programs. In addition, personality characteristics (e.g., goal orientation, optimism) and demographic characteristics (e.g., gender, race) also affect sport confidence.

Factors influencing sport confidence. It is hypothesized that organizational culture as well as demographic and personality characteristics influence sport confidence. Organizational culture represents the structural and cultural aspects of the sport subculture, which can include such things as level of competition, motivational climate, coaching behaviors, and expectations of different sport programs. In addition, personality characteristics (e.g., goal orientation, optimism) and demographic characteristics (e.g., gender, race) also affect sport confidence.

UNDERSTANDING HOW EXPECTATIONS INFLUENCE PERFORMANCE

Because self-confidence is the belief that one can successfully perform a desired behavior, one’s expectations play a critical role in the behavior change process. Research has shown that giving people a sugar pill for extreme pain (and telling them that it’s morphine) can produce as much relief as a painkiller. In essence, the powerful effect of expectations on performance is evident in many aspects of daily life, including sport and exercise. Keeping expectations high and maintaining confidence under adversity are important not only for athletes and exercisers but also for officials. Here is what a professional tennis umpire has said on the subject:

The chair umpire in tennis is a job that requires individuals who have confidence in themselves and are not easily shaken. The players hit the ball so hard and fast and close to the lines that it is virtually impossible to be absolutely certain of all the calls. But … you can’t start to doubt yourself, because once you do, you start to lose control of the match. In the end the players will respect you and your calls more if you show them that you are confident in your judgment and your abilities.

Self-Expectations and Performance

Some interesting studies have demonstrated the relation of expectations and performance. In one study, subjects were each paired with someone they thought (incorrectly) was clearly superior in arm strength and then instructed to arm wrestle (Nelson & Furst, 1972). Remarkably, in 10 of the 12 contests, the objectively weaker subject (who both subjects believed was stronger) won the competition. Clearly, the most important factor was not actual physical strength but who the competitors expected to win.

In other studies, two groups of participants were told that they were lifting either more weight or less weight than they actually were (Ness & Patton, 1979; Wells, Collins, & Hale, 1993). For example, someone who had already lifted 130 pounds was told he had been given 130 pounds again, when in fact he had been given 150 pounds, or vice versa. Subsequently, participants lifted the most weight when they thought they were lifting less—that is, when they believed and expected they could lift the weight.

Recent studies, as well as more classic studies (Mahoney & Avener, 1977), also showed that self-confidence was a critical factor in discriminating between successful and less successful performers (Gould, Guinan, et al., 1999; Jones et al., 1994; Mahoney et al., 1987). In addition, Maganaris, Collins, and Sharp (2000) reported that weightlifters who were told that they had been given anabolic steroids (but who had actually been given a placebo, saccharine) increased their performance, whereas performance decreased when lifters were told the true nature of the substance administered. Finally, more recently Greenlees, Bradley, Holder, and Thelwell (2005) found that other athletes’ behavior could influence expectations. Specifically, table tennis players who viewed other players exhibiting positive body language had more favorable impressions of the opponent and hence lower levels of outcome expectations (they believed they were going to lose) than when the opponent displayed negative body language. These studies demonstrate the critical role that self-expectations play in an athlete’s performance.

Coaching Expectations and Athletes’ Performance

The idea that a coach’s expectations could affect athletes’ performances evolved from a classic study. Rosenthal and Jacobson (1968) informed teachers that a standardized test of academic ability had identified certain children in each of their classes as “late bloomers” who could be expected to show big gains in academic achievement and IQ over the course of the school year. In fact, these children had been selected at random, so there was no reason to expect they would show greater academic progress than their classmates. But at the end of the school year, these so-called late bloomers did in fact achieve greater gains in IQ scores than the other children did. Rosenthal and Jacobson suggested that the false test information made the teachers expect higher performance from the targeted students, which led them to give these students more attention, reinforcement, and instruction (as demonstrated by a video of the teachers giving feedback to the students). The students’ performance and behavior thus conformed to the teachers’ expectations that they were gifted students.

Studies in physical education classrooms (Martinek, 1988) and competitive sport environments (Chase, Lirgg, & Feltz, 1997; Solomon, Striegel, Eliot, Heon, & Maas, 1996) also indicate that teachers’ and coaches’ expectations can alter their students’ and athletes’ performances. These studies showed that head coaches provided more of all types of feedback to athletes for whom they had high expectations and also that these athletes viewed their coaches more positively than did other athletes. In addition, the coaches’ expectations were a significant predictor of their athletes’ performances. A more recent study (Becker & Solomon, 2005) found that NCAA head basketball coaches used athletes’ hard work, receptivity to coaching, willingness to learn, love of the sport, and willingness to listen as the most important items in determining an athlete’s ability. These are all psychological attributes. Interestingly, physical attributes such as athleticism, coordination, and agility were not in the top 10 items for judging athletes’ ability. This process does not occur in all situations, because some teachers and coaches let their expectations affect their interaction with students and athletes but others do not. A sequence of events that occurs in athletic settings seems to explain the expectation–performance relationship (Horn, Lox, & Labrador, 2001).

Step 1: Coaches Form Expectations

Coaches usually form expectations of their athletes and teams. Sometimes these expectations come from an individual’s race, physical size, gender, or socioeconomic status. These expectations are called person cues. The exclusive use of person cues to form judgments about an athlete’s competence could certainly lead to inaccurate expectations. For example, some person cues such as gender, race, and body size could lead to inappropriate expectations. Interestingly enough, research (Becker & Solomon, 2005) indicates that psychological characteristics were the most salient factors that coaches relied on to judge athletic ability. This might be because at this level of competition, coaches believe that athletes are more likely to possess comparable levels of physical ability and thus it is psychological factors that really distinguish one athlete from another. However, coaches also use performance information, such as past accomplishments, skill tests, practice behaviors, and other coaches’ evaluations. When these sources of information lead to an accurate assessment of the athlete’s ability and potential, there’s no problem. However, inaccurate expectations (either too high or too low), especially when they are inflexible, typically lead to inappropriate behaviors on the part of the coach. This brings us to the second step in the sequence of events—coaches’ expectations influencing their behaviors.

Step 2: Coaches’ Expectations Influence Their Behaviors

Among teachers and coaches who behave differently if they have high or low expectancies of a given student or athlete, behaviors usually fit into one of the following categories:

Frequency and quality of coach–athlete interaction

Coach spends more time with “high-expectation” athletes because he expects more of them.

Coach spends more time with “high-expectation” athletes because he expects more of them.

Coach shows more warmth and positive affect toward high-expectation athletes.

Coach shows more warmth and positive affect toward high-expectation athletes.

Quantity and quality of instruction

Coach lowers her expectations of what skills some athletes will learn, thus establishing a lower standard of performance.

Coach lowers her expectations of what skills some athletes will learn, thus establishing a lower standard of performance.

Coach allows the athletes whom he expects less of correspondingly less time in practice drills.

Coach allows the athletes whom he expects less of correspondingly less time in practice drills.

Coach is less persistent in teaching difficult skills to these “low-expectation” athletes.

Coach is less persistent in teaching difficult skills to these “low-expectation” athletes.

Type and frequency of feedback

Coach provides more reinforcement and praise for high-expectation athletes after a successful performance.

Coach provides more reinforcement and praise for high-expectation athletes after a successful performance.

Coach provides quantitatively less beneficial feedback to low-expectation athletes, such as praise after a mediocre performance.

Coach provides quantitatively less beneficial feedback to low-expectation athletes, such as praise after a mediocre performance.

Coach gives high-expectation athletes more instructional and informational feedback.

Coach gives high-expectation athletes more instructional and informational feedback.

In addition to the type, quantity, and quality of feedback provided, teachers can exhibit their expectancies through the kind of environment they create. For example, when coaches create a more task- or learning-oriented environment, students do not perceive any differential treatment of high and low achievers. However, when teachers create an outcome-oriented environment focused on performance, then students perceive that their teachers favor high achievers as opposed to low achievers (Papaioannou, 1995).

Here is an example of how a coach’s expectations might affect her behavior. During the course of a volleyball game, Kira (whose coach has high expectations of her) attempts to spike the ball despite the fact that the setup was poor, pulling her away from the net. The spike goes into the net, but the coach says, “Good try, Kira, just try to get more elevation on your jump so you can contact the ball above the level of the net.” When Janet (whom the coach expects less of) does the same thing, the coach says, “Don’t try to spike the ball when you’re not in position, Janet. You’ll never make a point like that.”

Step 3: Coaches’ Behaviors Affect Athletes’ Performances

In this step, the coaches’ expectation-biased treatment of athletes affects performance both physically and psychologically. It is easy to understand that athletes who consistently receive more positive and instructional feedback from coaches will show more improvement in their performance and enjoy the competitive experience more. Look at these ways in which athletes are affected by the negatively biased expectations of their coaches:

Low-expectation athletes exhibit poorer performances because they receive less effective reinforcement and get less playing time.

Low-expectation athletes exhibit poorer performances because they receive less effective reinforcement and get less playing time.

Low-expectation athletes exhibit lower levels of self-confidence and perceived competence over the course of a season.

Low-expectation athletes exhibit lower levels of self-confidence and perceived competence over the course of a season.

Low-expectation athletes attribute their failures to lack of ability, thus substantiating the notion that they aren’t any good and have little chance of future success.

Low-expectation athletes attribute their failures to lack of ability, thus substantiating the notion that they aren’t any good and have little chance of future success.

Expectations and Behavior Guidelines for Coaches

The following recommendations are based on the literature regarding expectations of coaches (Horn, 2002; Horn et al., 2001):

1. Coaches should determine what sources of information they use to form preseason or early-season expectations for each athlete.

2. Coaches should realize that their initial assessment of an athlete’s competence may be inaccurate and thus needs to be revised continuously as the season progresses.

3. During practices, coaches need to keep a running count of the amount of time each athlete spends in non-skill-related activities (e.g., waiting in line).

4. Coaches should design instructional activities or drills that provide all athletes with an opportunity to improve their skills.

5. Coaches should generally respond to skill errors with corrective instructions about how to perform the skill correctly.

6. Coaches should emphasize skill improvement as a means of evaluating and reinforcing individual athletes rather than using absolute performance or levels of skill achievement.

7. Coaches should interact frequently with all athletes on their team to solicit information concerning athletes’ perceptions, opinions, and attitudes regarding team rules and organization.

8. Coaches should try to create a mastery-oriented environment in team practices, focused on improvement and team play.

Step 4: Athletes’ Performances Confirm the Coaches’ Expectations

Step 4, of course, communicates to coaches that they were correct in their initial assessment of the athletes’ ability and potential. Few coaches observe that their own behaviors and attitudes helped produce this result. Not all athletes allow a coach’s behavior or expectations to affect their performance or psychological reactions. Some athletes look to other sources, such as parents, peers, or other adults, to form perceptions of their competency and abilities. The support and information from these other people can often help athletes resist the biases communicated by a coach.

Clearly, sport and exercise professionals, including trainers and rehabilitation specialists, need to be aware of how they form expectations and how their behavior is affected. Early on, teachers and coaches should determine how they form expectations and whether their sources of information are reliable indicators of an individual’s ability. Coaches and teachers should also monitor the quantity and quality of reinforcement and instructional feedback they give so that they make sure all participants get their fair share. Such actions help ensure that all participants have a fair chance to reach their potential and enjoy the athletic experience. Based on research regarding coaching expectancy effects, “Expectations and Behavior Guidelines for Coaches” provides some behavioral recommendations for coaches.

Expectations and Judges’ Evaluation

There has been a lot of speculation regarding the impact of previous information and reputation on judges’ rating of performance (Baltes & Parker, 2000). In essence, are performers graded more leniently if they have had performance success in the past and possibly there are higher expectations of these performers? In one study (Findlay & Ste-Marie, 2004), figure skaters were evaluated by judges to whom the athletes were either known or unknown. Ordinal rankings were found to be higher when skaters were known by the judges compared with when they were unknown. Furthermore, skaters received higher technical merit marks when known, although artistic marks did not differ. Judges should be made aware of this potential bias, and skaters need to simply skate their best and not be affected by any potential bias because it is not under their control.

EXAMINING SELF-EFFICACY THEORY

Self-efficacy, the perception of one’s ability to perform a task successfully, is really a situation-specific form of self-confidence. For our purposes, we’ll use the terms self-efficacy and self-confidence interchangeably. Psychologist Albert Bandura (1977a, 1986, 1997) brought together the concepts of confidence and expectations to formulate a clear and useful conceptual model of self-efficacy. Later, Bandura (1997) redefined self-efficacy to encompass those beliefs regarding individuals’ capabilities to produce performances that will lead to anticipated outcomes. In this regard, the term self-regulatory efficacy is now used, which focuses more on one’s abilities to overcome obstacles or challenges to successful performance (e.g., carrying out one’s walking regimen when tired or during bad weather).

Bandura’s theory of self-efficacy has been adapted to explain behavior within several disciplines of psychology, and it has formed the theoretical basis adopted for most performance-oriented research in self-confidence and sport. The theory was originally developed within the framework of a social cognitive approach to behavior change that viewed self-efficacy as a common cognitive mechanism for mediating motivation and behavior. Consistent with the orientation of this textbook, self-efficacy theory takes an interactional approach, whereby self-efficacy (a person factor) and environmental determinants interact to produce behavior change in a reciprocal manner.

Bandura’s self-efficacy theory has several underlying premises, including the following:

If someone has the requisite skills and sufficient motivation, then the major determinant of the individual’s performance is self-efficacy. Self-efficacy alone cannot make a person successful—an athlete must also want to succeed and have the ability to succeed.

If someone has the requisite skills and sufficient motivation, then the major determinant of the individual’s performance is self-efficacy. Self-efficacy alone cannot make a person successful—an athlete must also want to succeed and have the ability to succeed.

Self-efficacy affects an athlete’s choice of activities, level of effort, and persistence. Athletes who believe in themselves will tend to persevere, especially under adverse conditions.

Self-efficacy affects an athlete’s choice of activities, level of effort, and persistence. Athletes who believe in themselves will tend to persevere, especially under adverse conditions.

Although self-efficacy is task specific, it can generalize, or transfer to other similar skills and situations.

Although self-efficacy is task specific, it can generalize, or transfer to other similar skills and situations.

Self-efficacy is related to goal setting: Those who exhibit high self-efficacy are more likely to set challenging goals.

Self-efficacy is related to goal setting: Those who exhibit high self-efficacy are more likely to set challenging goals.

Sources of Self-Efficacy

According to Bandura’s theory, one’s feelings of self-efficacy are derived from six principal sources of information: performance accomplishments, vicarious experiences (modeling), verbal persuasion, imaginal experiences, physiological states, and emotional states. The fact that these six sources of efficacy are readily applicable in sport and exercise contexts is largely responsible for the theory’s popularity among sport and exercise psychologists. These six categories or sources are not mutually exclusive in terms of the information they provide, although some are more influential than others. The relation between the major sources of efficacy information, efficacy expectations, and performance is diagrammed in figure 14.3. We’ll discuss each source in the sections that follow.

Performance Accomplishments

Performance accomplishments (particularly clear success or failure) provide the most dependable foundation for self-efficacy judgments because they are based on one’s mastery experiences. If experiences are generally successful, they will raise the level of self-efficacy. However, repeated failures result in expectations of lower efficacy. For example, if a field-goal kicker has kicked the winning field goal in several games as time was running out, he will have a high degree of self-efficacy that he can do it again. Similarly, an athlete rehabilitating from a wrist injury will persist in exercise after seeing steady improvement in her range of motion and wrist strength. Research on diving and gymnastics shows that performance accomplishments increase self-efficacy, which in turn increases subsequent performance (McAuley & Blissmer, 2002) as well as exercise adherence (McAuley, 1992, 1993a). Coaches and teachers can help participants experience the feeling of successful performance by using such tactics as guiding a gymnast through a complicated move, letting young baseball players play on a smaller field, providing progress charts and activity logs, or lowering the basket for young basketball players.

Vicarious Experiences

Physical educators, exercise leaders, athletic trainers, and coaches all often use vicarious experiences, also known as demonstration or modeling, to help students learn new skills. This can be a particularly important source of efficacy information for performers who lack experience with a task and rely on others to judge their own capabilities. For example, seeing a team member complete a difficult move on the uneven parallel bars can reduce anxiety and help convince other gymnasts that they, too, can accomplish this move. Studies found that people watching skilled models who were similar to the observers themselves experienced enhanced self-efficacy and performance (Gould, Weiss, & Weinberg, 1981; Lirgg & Feltz, 1991). The fitness and exercise videotapes and shows proliferating on television provide compelling examples of attempts to enhance efficacy expectations and behavior through modeling. Similarly, coaches view their own modeling of self-confidence as an important additional source of confidence for their athletes (Gould, Hodge, Peterson, & Giannini, 1989; Weinberg, Grove, & Jackson, 1992).

According to Bandura (1974; also see McCullagh, Weiss, & Ross, 1989), it is best to understand modeling as a four-stage process: attention, retention, motor reproduction, and motivation. To learn through watching, people must first give careful attention to the model. Our ability to attend to a model depends on respect for the person observed, interest in the activity, and how well we can see and hear. The best teachers and coaches focus on a few key points, demonstrate several times, and let you know exactly what to look for.

For people to learn effectively from modeling, they must commit the observed act to memory. Methods of accomplishing retention include mental practice techniques, use of analogies (e.g., telling the athlete to liken the tennis serve motion to throwing a racket), and having learners verbally repeat the main points aloud. The key is to help the observer remember the modeled act.

Even if people attend to demonstrated physical skills and remember how to do them, they still may not be able to perform the skills if they have not learned motor reproduction, that is, how to coordinate their muscle actions with their thoughts. For example, you could know exactly what a good approach and delivery in bowling look like and even be able to mimic the optimal physical action, but without physical practice to learn the timing, you will not roll strikes. When modeling sport and exercise skills, teachers and coaches must make sure they have taught lead-up skills, provided optimal practice time, and considered the progression to order related skills.

The final stage in the modeling process is motivation, which affects all the other stages. Without being motivated, an observer will not attend to the model, try to remember what was seen, and practice the skill. The key, then, is to motivate the observer by using praise, promising that the learner can earn rewards, communicating the importance of learning the modeled activity, or using models who will motivate the learner.

Verbal Persuasion

Coaches, teachers, and peers often use persuasive techniques to influence behavior. For example, a baseball coach may tell a player, “I know you’re a good hitter, so just hang in there and take your swings. The base hits will eventually come.” Similarly, an exercise leader may tell an exercise participant to “hang in there and don’t get discouraged, even if you have to miss a couple of days.” This type of encouragement is important to participants and can help improve self-efficacy (Weinberg, Gould, & Jackson, 1979) as well as enhance enjoyment, reduce perceived effort, and enhance affective responses (Hutchinson, Sherman, Martinovic, & Tenenbaum, 2008). Verbal persuasion to enhance confidence can also take the form of self-persuasion. Janel Jorgensen, silver medalist in the 100-meter butterfly in the 1988 Olympic Games, explained,

You have to believe it’s going to happen. You can’t doubt your abilities by saying, Oh I’m going to wake up tomorrow and I’m going to feel totally bad since I felt bad today and yesterday. You can’t go about it like that. You have to say O.K., tomorrow I’m going to feel good. I didn’t feel good today. That’s that. We will see what happens tomorrow. (Ripol, 1993, p. 36)

Even athletes’ belief that teammates are confident in them (regardless of whether this is true or not) will enhance their feelings of self-efficacy (Jackson, Beauchamp, & Knapp, 2007).

Imaginal Experiences

Individuals can generate beliefs about personal efficacy or lack of efficacy by imagining themselves or others behaving effectively or ineffectively in future situations. The key to using imagery as a source of confidence is to see oneself demonstrating mastery (Moritz et al., 1996). Chapter 13 provides a detailed discussion of the use of imagery in sport and exercise settings.

Physiological States

Physiological states influence self-efficacy when individuals associate aversive physiological arousal with poor performance, perceived incompetence, and perceived failure. Conversely, if physiological arousal is seen as facilitative, then self-efficacy is enhanced. Thus, when people become aware of unpleasant physiological arousal (e.g., racing heartbeat), they are more likely to doubt their competence than if they were experiencing pleasant physiological arousal (smooth, rhythmic breathing). For instance, some athletes may interpret increases in their physiological arousal or anxiety (such as a fast heartbeat or shallow breathing) as a fear that they cannot perform the skill successfully (lowered self-efficacy), whereas others might perceive such increases as a sign that they are ready for the upcoming competition (enhanced self-efficacy).

Emotional States

Although physiological cues are important components of emotions, emotional experiences are not simply the product of physiological arousal. Thus, emotions or moods can be an additional source of information about self-efficacy. For example, an injured athlete who is feeling depressed and anxious about his rehabilitation would probably have lowered feelings of self-efficacy. Conversely, an athlete who feels energized and positive would probably have enhanced feelings of self-efficacy. And, in fact, research has shown that positive emotional states such as happiness, exhilaration, and tranquility are more likely to enhance efficacy judgments than are negative emotional states such as sadness, anxiety, and depression (Maddux & Meier, 1995).

Reciprocal Relationship Between Efficacy and Behavior Change

Research has clearly indicated both that efficacy can act as a determinant of performance and exercise behavior and that exercise or sport behavior acts as a source of efficacy information (see Feltz & Lirgg, 2001; McAuley & Blissmer, 2002, for reviews). More specifically, a variety of studies have demonstrated that changes in efficacy correspond to changes in performance and exercise behavior, including the following findings:

Self-efficacy (among a host of social learning variables) was the best predictor of exercise in a 2-year large community sample.

Self-efficacy (among a host of social learning variables) was the best predictor of exercise in a 2-year large community sample.

Self-efficacy was particularly critical in predicting exercise behavior in older sedentary adults.

Self-efficacy was particularly critical in predicting exercise behavior in older sedentary adults.

Self-efficacy was a strong predictor of exercise in symptomatic populations.

Self-efficacy was a strong predictor of exercise in symptomatic populations.

Self-efficacy was a good predictor of exercise 9 months after program termination.

Self-efficacy was a good predictor of exercise 9 months after program termination.

Although the focus has been on efficacy as a determinant of exercise or sport behavior, there is also research indicating that exercise or sport behavior (both acute and chronic) can influence feelings of efficacy (e.g., McAuley & Katula, 1998). For example, keeping up one’s level of self-efficacy (especially regarding exercise behavior) would seem to be particularly important for older adults, who typically have some decrease in exercise function as they age. Therefore, if self-efficacy can be kept high via exercise, then the likelihood of continuing exercise also increases, which underscores the reciprocal nature of the efficacy–behavior relationship.

Self-Efficacy and Sport Performance

A number of studies have indicated that higher levels of self-efficacy are associated with superior performance (see Morris & Koehn, 2004, for a review). More specifically, analyses of 28 studies revealed that the correlations between self-efficacy and performance ranged from .19 to .73, with a median of .54. Thus, clearly, the perception of one’s ability to perform a task successfully has a consistent impact on actual performance.

These findings have held for a variety of individual and team sports. Because performance accomplishments are the strongest source of self-efficacy, it stands to reason that these enhance self-efficacy and then these increased feelings of self-efficacy have a positive effect on subsequent performance. Hence, we see a reciprocal relationship between self-efficacy and performance. This relationship is found in both anecdotal research and empirical studies.

ASSESSING SELF-CONFIDENCE

Now that you understand the relation of confidence or efficacy to performance and are aware that effectiveness can be hampered by overconfidence or underconfidence, the next step is to identify confidence levels in a variety of situations. Athletes might do this by answering the following questions:

When am I overconfident?

When am I overconfident?

How do I recover from mistakes?

How do I recover from mistakes?

When do I have self-doubts?

When do I have self-doubts?

Is my confidence consistent throughout an event?

Is my confidence consistent throughout an event?

Am I tentative and indecisive in certain situations?

Am I tentative and indecisive in certain situations?

Do I look forward to and enjoy tough, highly competitive games?

Do I look forward to and enjoy tough, highly competitive games?

How do I react to adversity?

How do I react to adversity?

The “Sport Confidence Inventory” on page 334 is a more formal and detailed assessment of self-confidence levels. To score your overall confidence, add up the percentages in the three columns and then divide by 10. The higher your score in the “Confident” column, the more likely you are to be at your optimal level of confidence during competition. High scores in the “Underconfident” or “Overconfident” columns indicate some potential problem areas. To determine specific strengths and weaknesses, look at each item. The scale assesses confidence in both physical and mental terms. You can use this questionnaire to inform yourself or others of what to work on.

Sources of Sport Self-Confidence

Researchers have identified nine sources of self-confidence specific to sport. Many of these are similar to the six sources that Bandura earlier identified in his self-efficacy theory. The nine sources fall into the three general categories of achievement, self-regulation, and climate.

Mastery: developing and improving skills

Mastery: developing and improving skills

Demonstration of ability: showing ability by winning and outperforming opponents

Demonstration of ability: showing ability by winning and outperforming opponents

Physical and mental preparation: staying focused on goals and being prepared to give maximum effort

Physical and mental preparation: staying focused on goals and being prepared to give maximum effort

Physical self-presentation: feeling good about one’s body and weight

Physical self-presentation: feeling good about one’s body and weight

Social support: getting encouragement from teammates, coaches, and family

Social support: getting encouragement from teammates, coaches, and family

Coaches’ leadership: trusting coaches’ decisions and believing in their abilities

Coaches’ leadership: trusting coaches’ decisions and believing in their abilities

Vicarious experience: seeing other athletes perform successfully

Vicarious experience: seeing other athletes perform successfully

Environmental comfort: feeling comfortable in the environment where one will perform

Environmental comfort: feeling comfortable in the environment where one will perform

Situational favorableness: seeing breaks going one’s way and feeling that everything is going right

Situational favorableness: seeing breaks going one’s way and feeling that everything is going right

More recently, Hays, Maynard, Thomas, and Bawden (2007) investigated sources of confidence in elite, world-class performers. Although a number of sources similar to those on the preceding list were noted, some additional sources emerged from these elite athletes. These included experience (having been there before), innate factors (natural ability, innate competitiveness), and competitive advantage (having seen competitors perform poorly or crack under pressure before). It is interesting to note that although both males and females derived confidence from performance accomplishments, males gained most confidence by winning in competition, whereas females gained most confidence by performing well and achieving personal goals.

BUILDING SELF-CONFIDENCE

Many people believe that you either have confidence or you don’t. Confidence can be built, however, through work, practice, and planning. Jimmy Connors is a good example. Throughout his junior playing days, Connors’ mother taught him to always hit out and go for winners. Because of this playing style, he lost some matches he should have won. Yet Connors said he never could have made it without his mother and grandmother. “They were so sensational in their support, they never allowed me to lose confidence. They just kept telling me to play the same way, and they kept assuring me that it would eventually come together. And I believed them” (Tarshis, 1977, p. 102).

Confidence can be improved in a variety of ways: accomplishing through performance, acting confident, thinking confidently, using imagery, using goal mapping, optimizing physical conditioning, and preparing. Both athletes (Myers, Vargas-Tonsing, & Feltz, 2005) and coaches (Gould et al., 1989) generally agree on these confidence-building activities. We will consider each of these in turn.

Focusing on Performance Accomplishments

We have already discussed the influence of performance accomplishments on self-efficacy, but we’ll elaborate on some of those points here. The concept is simple: Successful behavior increases confidence and leads to further successful behavior. The successful accomplishment might be beating a particular opponent, coming from behind to win, fully extending your knee during rehabilitation, or exercising continuously for 30 minutes. Of course, when a team loses eight games in a row, it will be hard-pressed to feel confident about winning the next game, especially against a good team. Confidence is crucial to success, but how can you be confident without previous success? This appears to be a catch-22 situation: As one coach put it, “We’re losing now because we’re not feeling confident, but I think the reason the players don’t feel confident is that they have been losing.”

You are certainly more likely to feel confident about performing a certain skill if you can consistently execute it during practice. That’s why good practices and preparing physically, technically, and tactically to play your best enhance confidence. Nothing elicits confidence like experiencing in practice what to accomplish in the competition. Similarly, an athlete rehabilitating a shoulder separation needs to experience some success in improving range of motion to keep up her confidence that she will eventually regain full range of motion. Short-term goals can help her believe she has made progress and can enhance her confidence (also see chapter 15). A coach should structure practices to simulate actual performance conditions. For example, if foul shooting under pressure has been a problem in the past, each player should sprint up and down the floor several times before shooting any free throw (because this is what happens during a game). Furthermore, to create pressure, a coach might require all players to make five free throws in a row or to continue this drill until they do so.

Acting Confident

Thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are interrelated: The more confident an athlete acts, the more likely he is to feel confident. This is especially important when an athlete begins to lose confidence and the opponent, sensing this, begins to gain confidence. Acting confident is also important for sport and exercise professionals, because this models behavior you’d like participants to have. An aerobics instructor should project confidence when leading her class if she wants to have a high-spirited workout. An athletic trainer should act confident when treating athletes so that they feel trust and confidence during the rehabilitation process. Athletes should try to display a confident image during competition. They can demonstrate their confidence by keeping their head up high—even after a critical error. Many people give themselves away through body language and movements that indicate they are lacking confidence. Acting confident can also lift spirits during difficult times. If someone walks around with slumped shoulders, head down, and a pained facial expression, he communicates to all observers that he is down, which pulls him even further down. It is best to keep your head up, shoulders back, and facial muscles loose to indicate that you are confident and will persevere. This keeps opponents guessing.

Self-Efficacy in Coaches

A relatively recent addition to the self-efficacy literature has been research on coaching efficacy. Feltz and colleagues (Feltz et al., 1999; Malete & Feltz, 2000) have developed the notion of coaching efficacy, defined as the extent to which coaches believe they have the capacity to affect the learning and performance of their athletes. These authors’ concept of coaching efficacy comprises the following four areas:

Game strategy: confidence that coaches have in their ability to coach during competition and lead their team to a successful performance

Game strategy: confidence that coaches have in their ability to coach during competition and lead their team to a successful performance

Motivation: confidence that coaches have in their ability to affect the psychological skills and states of their athletes

Motivation: confidence that coaches have in their ability to affect the psychological skills and states of their athletes

Technique: confidence that coaches have in their instructional and diagnostic skills

Technique: confidence that coaches have in their instructional and diagnostic skills

Character building: confidence that coaches have in their ability to influence a positive attitude toward sport in their athletes

Character building: confidence that coaches have in their ability to influence a positive attitude toward sport in their athletes

Some recent findings regarding coaching efficacy include the following:

The most important sources of coaching efficacy were years of experience and community support, although past winning percentage, perceived team ability, and parental support also were related to feelings of coaching efficacy.

The most important sources of coaching efficacy were years of experience and community support, although past winning percentage, perceived team ability, and parental support also were related to feelings of coaching efficacy.

Coaches with higher efficacy had higher winning percentages, had players with higher levels of satisfaction, used more praise and encouragement, and used fewer instructional and organizational behaviors than coaches with low efficacy.

Coaches with higher efficacy had higher winning percentages, had players with higher levels of satisfaction, used more praise and encouragement, and used fewer instructional and organizational behaviors than coaches with low efficacy.

A coaching education program enhanced perceptions of coaching efficacy compared with a control condition.

A coaching education program enhanced perceptions of coaching efficacy compared with a control condition.

Male assistant coaches (compared with females) had higher levels of coaching efficacy and desire to become a head coach, whereas females had greater occupational turnover intentions (Cunningham, Sagas, & Ashley, 2003). Social support was a stronger source of efficacy for female coaches than for male coaches (Myers, Vargas-Tonsing, & Feltz 2005).

Male assistant coaches (compared with females) had higher levels of coaching efficacy and desire to become a head coach, whereas females had greater occupational turnover intentions (Cunningham, Sagas, & Ashley, 2003). Social support was a stronger source of efficacy for female coaches than for male coaches (Myers, Vargas-Tonsing, & Feltz 2005).

The most frequently cited source of coaching efficacy was player development (Chase, Feltz, Hayashi, & Hepler, 2005). This was seen in such things as getting players to play hard, teaching team roles, developing players’ skills, and having confidence in the team.

The most frequently cited source of coaching efficacy was player development (Chase, Feltz, Hayashi, & Hepler, 2005). This was seen in such things as getting players to play hard, teaching team roles, developing players’ skills, and having confidence in the team.

Athletes felt that coaches who were efficacious in the different aspects of coaching helped them to enjoy their experience more and try harder (motivation efficacy), develop more confidence (technique efficacy), and improve prosocial behavior (character-building efficacy) (Boardley, Kavussanu, & Ring, 2008).

Athletes felt that coaches who were efficacious in the different aspects of coaching helped them to enjoy their experience more and try harder (motivation efficacy), develop more confidence (technique efficacy), and improve prosocial behavior (character-building efficacy) (Boardley, Kavussanu, & Ring, 2008).

Coaches who were higher on coaching efficacy felt they were better able to control their emotions and were generally higher on emotional intelligence (Thelwell, Lane, Weston, & Greenlees, 2008).

Coaches who were higher on coaching efficacy felt they were better able to control their emotions and were generally higher on emotional intelligence (Thelwell, Lane, Weston, & Greenlees, 2008).

Coaches had higher perceptions of their coaching efficacy than did their athletes (Kavussanu et al., 2008).

Coaches had higher perceptions of their coaching efficacy than did their athletes (Kavussanu et al., 2008).

Thinking Confidently

Confidence consists of thinking that you can and will achieve your goals. As a collegiate golfer noted, “If I think I can win, I’m awfully tough to beat.” A positive attitude is essential to reaching potential. Athletic performers need to discard negative thoughts (I’m so stupid; I can’t believe I’m playing so bad; I just can’t beat this person; or I’ll never make it) and replace them with positive thoughts (I’ll keep getting better if I just work at it; Just keep calm and focused; I can beat this guy; or Hang in there and things will get better). Thoughts and self-talk should be instructional and motivational rather than judgmental (see chapter 16). In fact, positive self-talk not only can provide specific performance cues but also can keep motivation and energy high. Although it is sometimes difficult to do, positive self-talk results in a more enjoyable and successful athletic experience, making it well worth using.

Collective Efficacy: A Special Case of Self-Efficacy

Another focus of research has been on the concept of collective, or team, efficacy. Collective efficacy refers to a belief or perception shared by members of the team regarding the capabilities of their teammates (rather than merely the sum of individual perceptions of efficacy). In short, collective efficacy is each individual’s perception of the efficacy of the team as a whole. Research (Lichacz & Partington, 1996; Lirgg & Feltz, 1994, 2001) demonstrated that athletes’ belief in the team’s total (collective) efficacy was positively related to performance; the sum of the individuals’ personal self-efficacy, however, was not related to team performance. In essence, coaches should be more concerned with building the efficacy of the team as a whole than with each individual player’s self-efficacy. Along these lines, it appears that practice performance is even a more important source of collective efficacy than previous game performance. In addition, events outside of the sport realm (e.g., personal life problems, relationships with friends, school demands) are less important for team than is self-efficacy (Chase, Feltz, & Lirgg, 2003).

Creating a belief in the team and its ability to be successful as a group appears to be critical to success. Many of the great teams (Chicago Bulls, Boston Celtics, New York Yankees, Montreal Canadians, San Francisco 49ers) have had this sense of team efficacy during their winning years. Therefore, to enhance performance and productivity—whether you are a coach, teacher, exercise leader, or head athletic trainer—it seems crucial that you get your team, group, or class to believe in themselves as a unit (as opposed to simply believing in themselves individually). In addition, recent research has revealed that creating a mastery-oriented climate (focus on performance improvement instead of winning) will also enhance feelings of collective efficacy (Magyar, Feltz, & Simpson, 2004). Finally, in a review of the literature in this area, Shearer, Holmes, and Mellalieu (2009) argue from a neuroscience perspective that imagery and observation-based interventions (e.g., video footage of successful team plays and interactions) are particularly effective in building collective efficacy especially when an individual’s perspective is directed toward his teammates’ perspectives (e.g., My team believes . . .).

Using Imagery

As you can recall from chapter 13, one use of imagery is to help build confidence. You can see yourself doing things that you either have never been able to do or have had difficulty doing. For example, a golfer who consistently has been slicing the ball off the tee can imagine herself hitting the ball straight down the fairway. A football quarterback can visualize different defensive alignments and then try to counteract these with specific plays and formations. Similarly, trainers can help injured athletes build confidence by having them imagine getting back on the playing field and performing well. The use of imagery to build confidence is seen in the following quote by an Olympic pistol shooter:

I would imagine to myself, “How would a champion act and feel….” This helped me to find out about myself. Then as the actual roles I had imagined came along, and as I achieved them, that in turn helped me to believe that I would be the Olympic champion. (Orlick & Partington, 1988, p. 113)

Using Goal Mapping

Because the focused and persistent pursuit of goals serves as a basic regulator of human behavior, it is important to use goal mapping to enhance the confidence and performance of athletes. A goal map is a personalized plan for an athlete that contains various types of goals and goal strategies as well as a systematic evaluation procedure to assess progress toward goals (see chapter 15 for a detailed discussion of goal setting). Research and interviews with both coaches and athletes indicate that the focus should be more on performance and process goals, as opposed to outcome goals, because the former provide more of a sense of control and enhanced attention to the task. Goal mapping, imagery, and self-talk are three primary self-regulatory tools advocated by sport psychologists to enhance confidence.

Building Coaching Efficacy