After reading this chapter, you should be able to

1. discuss the role of psychological factors in athletic and exercise injuries,

2. identify psychological antecedents that may predispose people to athletic injuries,

3. compare and contrast explanations for the stress–injury relationship,

4. describe typical psychological reactions to injuries,

5. identify signs of poor adjustment to injury, and

6. explain how to implement psychological skills and strategies that can speed the rehabilitation process.

Ask anyone who has experienced a sport-related injury, and he will say that his injury experience involved not only a physical dysfunction, but a number of psychological issues as well. It is not uncommon for injured athletes to feel isolated, frustrated, anxious, and depressed. And it is not just our psychological reactions to being injured that are issues. Sport and exercise participants who are experiencing major life stress or changes and who do not have good strategies for dealing with these stresses are more likely to be injured. Finally, anyone who has rehabilitated from a major athletic injury knows that issues like motivation and goal setting are involved in a successful recovery and return to play.

Not only is being injured a significant life event, but it is one that happens quite often. It is estimated that over 25 million people are injured each year in the United States in sport, exercise, and recreational settings (Williams & Anderson, 2007). For example, approximately 3.5 million U.S. children ages 14 and under are injured playing sports or participating in recreational activities yearly (National Safe Kids Campaign, 2004). It is also estimated that the number of recreation- and sport-related injury emergency room visits is 3.7 million in the United States (Burt & Overbeck, 2001). Finally, data from Sweden show that 75% of elite soccer players will suffer an injury sometime during a season (Luthje, Nurmi, Kataga, Belt, Helenius, & Kaukonen, 1996).

Physical factors are the primary causes of athletic injuries, but psychological factors can also contribute. Recent evidence also shows that psychological factors play a key role in injury rehabilitation. Thus, fitness professionals should understand both the psychological reactions to injuries and the ways in which mental strategies can facilitate recovery. In fact, in a recent survey of over 800 sports medicine physicians, 80% indicated that they often or sometimes discussed emotional and behavioral problems related to injury with patient-athletes (Mann, Grana, Indelicato, O’Neil, & George, 2007). These physicians most often discussed the psychological issues of stress or pressure, anxiety, and burnout with their patients.

Sport psychologists Jean Williams and Mark Andersen (Andersen & Williams, 1988; Williams & Andersen, 1998, 2007) have helped clarify the role that psychological factors play in athletic injuries. Figure 19.1 shows a simplified version of their model. You can see that in this model, the relation between athletic injuries and psychological factors centers on stress. In particular, a potentially stressful athletic situation (e.g., competition, important practice, poor performance) can contribute to injury, depending on the athlete and how threatening he perceives the situation to be (see chapter 4). A situation perceived as threatening increases state anxiety, which causes a variety of changes in focus or attention and muscle tension (e.g., distraction and tightening up). This in turn leads to an increased chance of injury.

Stress isn’t the only psychological factor to influence athletic injuries, however. As you also see in figure 19.1, personality factors, a history of stressors, and coping resources all influence the stress process and, in turn, the probability of injury. Furthermore, after someone sustains an injury, these same factors influence how much stress the injury causes and the individual’s subsequent rehabilitation and recovery. Moreover, people who develop psychological skills (e.g., goal setting, imagery, and relaxation) deal better with stress, reducing both their chances of being injured and the stress of injury should it occur. It has also been suggested that the stress–athletic injury model can be extended to explain not only physical injuries but also physical illnesses that may result from the combination of intense physical training and psychosocial variables (Petrie & Perna, 2004). Thus, the model may also be useful in explaining why athletes develop infections, poor adaption to training and physical complaints when highly stressed. With this overview of the roles that psychological factors can play in athletic- and exercise-related injuries, we can now examine in more depth the pieces of the model.

HOW INJURIES HAPPEN

Physical factors, such as muscle imbalances, high-speed collisions, overtraining, and physical fatigue, are the primary causes of exercise and sport injuries. However, psychological factors have also been found to play a role. Personality factors, stress levels, and certain predisposing attitudes have all been identified (Rotella & Heyman, 1986; Wiese & Weiss, 1987; Williams & Andersen, 2007) as psychological antecedents to athletic and physical activity injuries. In fact, in one recent study, up to 18% of time loss because of injury was explained by psychosocial factors (Smith, Ptacek, & Patterson, 2000).

Personality Factors

Personality traits were among the first psychological factors to be associated with athletic injuries. Investigators wanted to understand whether such traits as self-concept, introversion–extroversion, and tough-mindedness were related to injury. For example, would athletes with low self-concepts have higher injury rates than their counterparts with high self-concepts? Unfortunately, most of the research on personality and injury has suffered from inconsistency and the problems that have plagued sport personality research in general (Feltz, 1984a; also see chapter 2). Of course, this does not mean that personality is not related to injury rates; it means that to date we have not successfully identified and measured the particular personality characteristics associated with athletic injuries. In fact, recent evidence (Ford, Eklund, & Gordan, 2000; Smith et al., 2000) shows that personality factors such as optimism, self-esteem, hardiness, and trait anxiety do play a role in athletic injuries. However, this role is more complex than first thought, because personality factors tend to moderate the stress–injury relationship. That is, if a person is characterized by high trait anxiety, the life stress–injury relationship may be stronger than in a person who is low trait anxious.

Stress Levels

Stress levels, on the other hand, have been identified as important antecedents of athletic injuries. Research has examined the relation between life stress and injury rates (Andersen & Williams, 1988; Johnson, 2007; Williams & Andersen, 1998, 2007). Measures of these stresses focus on major life changes, such as losing a loved one, moving to a different town, getting married, or experiencing a change in economic status. Such minor stressors and daily hassles as driving in traffic have also been studied. Overall, the evidence suggests that athletes with higher levels of life stress experience more injuries than those with less stress in their lives, with 85% of the studies verifying that this relationship exists (Williams & Andersen, 2007). Thus, fitness and sport professionals should ask about major changes and stressors in athletes’ lives and, when such changes occur, carefully monitor and adjust training regimens as well as provide psychological support.

Stress and injuries are related in complex ways. A study of 452 male and female high school athletes (in basketball, wrestling, and gymnastics) addressed the relation between stressful life events; social and emotional support from family, friends, and coaches; coping skills; and the number of days athletes could not participate in their sport because of injury (Smith, Smoll, & Ptacek, 1990). No relation was found among these factors across a school season. However, life stress was associated with athletic injuries in the specific subgroup of athletes who had both low levels of social support and low coping skills. These results suggest that when an athlete possessing few coping skills and little social support experiences major life changes, he or she is at a greater risk of athletic injury. Similarly, individuals who have low self-esteem, are pessimistic and low in hardiness (Ford et al., 2000), or have higher levels of trait anxiety (Smith et al., 2000) experience more athletic injuries or lose more time as a result of their injuries. Certified athletic trainers and coaches should be on the lookout for these at-risk individuals. This finding supports the Andersen and Williams model, emphasizing the importance of looking at the multiple psychological factors in the stress–injury relationship.

According to recent studies, athletes at high risk of being injured experienced fewer injuries after stress management training interventions than their high-risk counterparts who did not take part in such training

(Johnson, Ekengren, & Andersen, 2005; Maddison & Prapavessis, 2005). For example, Maddison and Prapavessis (2005) had 48 rugby players at risk of injury (low in social support and high in avoidance coping) randomly assigned to a stress management training or no-training control condition. The stress management training involved progressive muscle relaxation, imagery thought management, goal setting, and planning. Results revealed that those in stress management training missed less time due to injuries and experienced an increase in coping resources and decreased worry following completion of the program.

Research has also identified the specific stress sources for athletes when injured and when rehabilitating from injury (Gould, Udry, Bridges, & Beck, 1997b; Podlog & Eklund, 2006). Interestingly, the greatest sources of stress were not the result of the physical aspects of the injuries. Rather, psychological reactions (e.g., fear of reinjury, feeling that hopes and dreams were shattered, watching others get to perform) and social concerns (e.g., lack of attention, isolation, negative relationships) were mentioned more often as stressors (Gould et al., 1997b). For example, one elite skier commented:

I felt shut up, cut off from the ski team. That was one of the problems I had. I didn’t feel like I was being cared for, basically. Once I got home, it was like they (the ski team) dropped me off at home, threw all my luggage in the house, and were [saying] like “See you when you get done.” I had a real hard time with that.

Another injured athlete said:

I [have a fear of reinjury] because I had a few recurrences and I hurt it a few times. So when I’m training now I’m always thinking about it and if it feels uncomfortable I think maybe something is going to happen. (Podlog & Eklund, 2006, p. 55)

Other stress concerns (stresses) that athletes experienced involved physical problems (e.g., pain, physical inactivity), medical treatment (e.g., medical uncertainty, seriousness of diagnosis), rehabilitation difficulties (e.g., dealing with slow progress, rehabbing on their own), financial difficulties, career worries, and their sense of missed opportunities (Gould et al., 1997b). Being familiar with these stress sources is important for the people working with injured athletes.

Teaching stress management techniques (see chapter 12) not only may help athletes and exercisers perform more effectively but also may reduce their risk of injury and illness. In a well-designed clinical trials study, collegiate rowers who were randomly assigned to a cognitive behavioral stress management training versus control condition (those who received only the conceptual elements of the program, but not the actual skills training) experienced fewer days lost to injury or illness across a season (Perna, Antoni, Baum, Gordon, & Schneiderman, 2003), verifying in a more controlled study earlier results found with competitive gymnasts (Kerr & Goss, 1996). Several other studies (Johnson et al., 2005; Maddison & Prapavessis, 2005) have also verified the effectiveness of stress management training on reducing injuries in athletes.

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN STRESS AND INJURY

Understanding why athletes who experience high stress in life are more prone to injury can significantly help you in designing effective sports medicine programs to deal with stress reactions and injury prevention. Two major theories have been advanced to explain the stress–injury relationship.

Attentional Disruption

One promising view is that stress disrupts an athlete’s attention by reducing peripheral attention (Williams, Tonyman, & Andersen, 1991). Thus, a football quarterback under great stress might be prone to injury because he does not see a charging defender rushing in from his off side. When his stress levels are lower, the quarterback has a wider field of peripheral attention and is able to see the defender in time to avoid a sack and subsequent injury. It has also been suggested that increased state anxiety causes distraction and irrelevant thoughts. For instance, an executive who jogs at lunch after an argument with a colleague might be inattentive to the running path and step into a hole, twisting her ankle.

Increased Muscle Tension

High stress can be accompanied by considerable muscle tension that interferes with normal coordination and increases the chance of injury (Smith et al., 2000). For example, a highly stressed gymnast might experience more muscle tension than is desirable and fall from the balance beam, injuring himself. Increased stress may also lead to generalized fatigue, muscle inefficiency, reduced flexibility, and motor coordination problems (Williams & Andersen, 2007). Teachers and coaches who work with an athlete experiencing major life changes (e.g., a high school student whose parents are in the midst of a divorce) should watch the athlete’s behavior closely. If she shows signs of increased muscle tension or abnormal attentional difficulties when performing, it would be wise to ease training and initiate stress management strategies.

Other Psychologically Based Explanations for Injury

In addition to stress, sport psychologists working with injured athletes have identified certain attitudes that predispose players to injury. Rotella and Heyman (1986) observed that attitudes held by some coaches—such as “Act tough and always give 110%” or “If you’re injured, you’re worthless”—can increase the probability of athlete injury.

Act Tough and Give 110%

Slogans such as “Go hard or go home,” “No pain, no gain,” and “Go for the burn” typify the 110%-effort orientation many coaches promote. By rewarding such effort without also emphasizing the need to recognize and accept injuries, coaches encourage their athletes to play hurt or take undue risks (Rotella & Heyman, 1986). A college football player, for instance, may be repeatedly rewarded for sacrificing his body on special teams. He becomes ever more daring, running down to cover kickoffs, until one day he throws his body into another player and sustains a serious injury.

This is not to say that athletes should not play assertively and hit hard in football, wrestling, and rugby. But giving 110% should not be emphasized so much that athletes take undue risks—such as spearing or tackling with the head down in football—and increase their chances of severe injuries.

The act-tough orientation is not limited to contact sports. Many athletes and exercisers are socialized into believing that they must train through pain and that “more is always better.” They consequently overstrain and are stricken with tennis elbow, shinsplints, swimmer’s shoulder, or other injuries. Some sports medicine professionals believe that these types of overuse injuries are on the rise, especially in young athletes (DiFiori, 2002; Hutchinson & Ireland, 2003). Hard physical training does involve discomfort, but athletes and exercisers must be taught to distinguish the normal discomfort that accompanies overloading and increased training volumes from the pain that accompanies the onset of injuries.

If You’re Injured, You’re Worthless

Some people learn to feel worthless if they are hurt, an attitude that develops in several ways. Coaches may convey, consciously or otherwise, that winning is more important than the athlete’s well-being. When a player is hurt, that player no longer contributes toward winning. Thus, the coach has no use for the player—and the player quickly picks up on this. Athletes want to feel worthy (like winners), so they play while hurt and sustain even worse injuries. A less direct way of conveying this attitude that injury means worthlessness is to say the “correct” thing (e.g., “Tell me when you’re hurting! Your health is more important than winning”) but then act very differently when a player is hurt. The player is ignored, which tells him that to be hurt is to be less worthy. Athletes quickly adopt the attitude that they should play even when they are hurt. The “Injury Pain and Training Discomfort” case study shows how athletes should be encouraged to train hard without risking injury.

Injury Pain and Training Discomfort

Sharon Taylor coaches a swimming team that has been plagued over the years by overuse injuries. Yet her team is proud of its hard-work ethic. Incorporating swimming psychologist Keith Bell’s guidelines (1980), Sharon taught the team to view the normal discomfort of training (pain) as a sign of growth and progress, as opposed to something awful or intolerable. For her team, normal training discomfort is not a signal to stop but a challenge to do more.

Because along the way Sharon’s swimmers took their training philosophy too far and misinterpreted Bell’s point, Sharon set a goal of having her swimmers distinguish between the discomfort of training and the pain of injury. At the start of the season she discussed her concerns and asked swimmers who had sustained overuse injuries during the preceding season to talk about the differences between pushing through workouts (overcoming discomfort) and ignoring injury (e.g., not stopping or telling the coach when a shoulder ached). She changed the team slogan from “No pain, no gain” to “Train hard and smart.” She also revamped the training cycling scheme to include more days off and initiated a team rule that no one could swim or lift weights on the days off. Sharon periodically discussed injury in contrast to discomfort with her swimmers during the season, and she reinforced correct behavior with praise and occasional rewards. Sharon informed the parents of her swimmers about the need to monitor their children’s chronic pains.

As the season progressed, the swimmers began to understand the difference between injury pain and the normal discomfort of hard training. At the end of the season, most of the swimmers had remained healthy and were excited about the state meet.

PSYCHOLOGICAL REACTIONS TO EXERCISE AND ATHLETIC INJURIES

Despite taking physical and psychological precautions, many people engaged in vigorous physical activity sustain injuries. Even in the best-staffed, best-equipped, and best-supervised programs, injury is inherently a risk. So it is important to understand psychological reactions to activity injuries. Sport psychology specialists and athletic trainers have identified varied psychological reactions to injuries. Some people view an injury as a disaster. Others may view their injury as a relief—a way to get a break from tedious practices, save face if they are not playing well, or even have an acceptable excuse for quitting. Although many different reactions can occur, some are more common than others. Sport and fitness professionals must observe these responses.

Emotional Responses

As they began to examine the psychology of injury in athletes, sport psychologists first speculated that people’s reaction to athletic or exercise-related injury was similar to the response of people facing imminent death. According to this view, exercisers and athletes who have become injured often follow a five-stage grief response process (Hardy & Crace, 1990). These stages are

1. denial,

2. anger,

3. bargaining,

4. depression, and

5. acceptance and reorganization.

This grief reaction has been widely cited in articles about the psychology of injury, but evidence shows that although individuals may exhibit many of these emotions in response to being injured, they do not follow a set, stereotypical pattern or necessarily experience each emotion in these five stages (Brewer, 1994; Evans & Hardy, 1995; Quinn & Fallon, 1999; Udry, Gould, Bridges, & Beck, 1997). Sport psychologists now recommend that we view typical responses to injury in a more flexible and general way—people do not move neatly through set stages in a predetermined order. Rather, many have more than one of these emotions and thoughts simultaneously or revert back to stages that they have experienced previously. Nevertheless, although emotional responses to being injured have not proved to be as fixed or orderly as sport psychologists once thought, you can expect injured individuals to exhibit three general categories of responses (Udry et al., 1997):

1. Injury-relevant information processing. The injured athlete focuses on information related to the pain of the injury, awareness of the extent of injury, and questions about how the injury happened, and the individual recognizes the negative consequences or inconvenience.

2. Emotional upheaval and reactive behavior. Once the athlete realizes that she is injured, she may become emotionally agitated; experience vacillating emotions; feel emotionally depleted; experience isolation and disconnection; and feel shock, disbelief, denial, or self-pity.

3. Positive outlook and coping. The athlete accepts the injury and deals with it, initiates positive coping efforts, exhibits a good attitude and is optimistic, and is relieved to sense progress. In reaction to injury, most athletes move through these general patterns; but the speed and ease with which they progress vary widely. One person may move through the process in a day or two; others may take weeks or even months to do so. However, one long-term study of 136 severely injured Australian athletes showed that the period immediately following the injury was characterized by the greatest negative emotions (Quinn & Fallon, 1999).

Other Reactions

Athletes experience additional psychological reactions to injury (Petitpas & Danish, 1995). These are some of their other reactions:

1. Identity loss. Some athletes who can no longer participate because of an injury experience a loss of personal identity. That is, an important part of themselves is lost, seriously affecting self-concept.

2. Fear and anxiety. When injured, many athletes experience high levels of fear and anxiety. They worry whether they will recover, whether reinjury will occur, and whether someone will replace them permanently in the lineup. Because the athlete cannot practice and compete, there’s plenty of time for worry.

3. Lack of confidence. Given the inability to practice and compete and their deteriorated physical status, athletes may lose confidence after an injury. Lowered confidence can result in decreased motivation, inferior performance, or even additional injury if the athlete overcompensates.

4. Performance decrements. Because of lowered confidence and missed practice time, athletes may experience postinjury performance declines. Many athletes have difficulty lowering their expectations after an injury and may expect to return to a preinjury level of performance.

Physiological Components of Injury Recovery

One of the most interesting research developments in medicine deals with how psychological stress and emotions influence the physiology of injury recovery. Cramer Roh, and Perna (2000), for example, indicated that the body’s natural healing process can be disrupted by high levels of depression and stress. Specifically, these authors contended that psychological stress increases catecholamines and glucocorticoids, which impair the movement of healing immune cells to the site of the injury and interfere with the removal of damaged tissue. Prolonged stress may also decrease the actions of insulin-like growth hormones that are critical during the rebuilding process. Finally, stress is also believed to cause sleep disturbance, another factor identified to interfere with physiological recovery (Perna et al., 2003).

The loss of personal identity is especially significant to athletes who define themselves solely through sport. People who sustain a career- or activity-ending injury may require special, often long-term, psychological care.

Signs of Poor Adjustment to Injury

Most people work through their responses to injury, showing some negative emotions but not great difficulty in coping. One national survey of athletic trainers revealed that they refer 8% of their injured clients to psychological counseling (Larson, Starkey, & Zaichkowsky, 1996). How can you tell whether an athlete or exerciser exhibits a “normal” injury response or is having serious difficulties that require special attention? The following symptoms are warning signs of poor adjustment to athletic injuries (Petitpas & Danish, 1995):

Feelings of anger and confusion

Feelings of anger and confusion

Obsession with the question of when one can return to play

Obsession with the question of when one can return to play

Denial (e.g., “The injury is no big deal”)

Denial (e.g., “The injury is no big deal”)

Repeatedly coming back too soon and experiencing reinjury

Repeatedly coming back too soon and experiencing reinjury

Exaggerated bragging about accomplishments

Exaggerated bragging about accomplishments

Dwelling on minor physical complaints

Dwelling on minor physical complaints

Guilt about letting the team down

Guilt about letting the team down

Withdrawal from significant others

Withdrawal from significant others

Rapid mood swings

Rapid mood swings

Statements indicating that no matter what is done, recovery will not occur

Statements indicating that no matter what is done, recovery will not occur

A fitness instructor or coach who observes someone with these symptoms should discuss the situation with a sports medicine specialist and suggest the specialized help of a sport psychologist or counselor. Similarly, a certified athletic trainer who notices these abnormal emotional reactions to injuries should make a referral to a sport psychologist or another qualified mental health provider just as she should if an uninjured athlete exhibits general life issues (e.g., depression, severe generalized anxiety) of a clinical nature.

Finally, psychological reactions to being injured do not necessarily stop when an athlete or exerciser is cleared to return to full physical activity. In a longitudinal study of athletes recovering from serious injuries, Podlog and Eklund (2006) identified a number of return-to-play concerns, which included overcoming reinjury fears, concerns with being able to reach preinjury performance levels, dealing with differences in pain, and seeing performance improvements.

ROLE OF SPORT PSYCHOLOGY IN INJURY REHABILITATION

Tremendous gains have been made in recent years in the rehabilitation of athletic and exercise-related injuries. An active recovery, less invasive surgical techniques, and weight training are among these advances in rehabilitation. New psychological techniques also facilitate the injury recovery process, and professionals increasingly use a holistic approach to healing both the mind and body. Understanding the psychology of injury recovery is important for everyone involved in sport and exercise.

Psychology of Recovery

In one study of how psychological strategies help injury rehabilitation, Ievleva and Orlick (1991) examined whether athletes with fast-healing (fewer than 5 weeks) knee and ankle injuries demonstrated greater use of psychological strategies and skills than those with slow-healing (more than 16 weeks) injuries. The researchers conducted interviews, assessing attitude and outlook, stress and stress control, social support, positive self-talk, healing imagery, goal setting, and beliefs. They found that fast-healing athletes used more goal-setting and positive self-talk strategies and, to a lesser degree, more healing imagery than did slow-healing athletes.

More recent studies have also shown that psychological interventions positively influenced athletic injury recovery (Cupal & Brewer, 2001), mood during recovery (Johnson, 2000), coping (Evans, Hardy, & Fleming, 2000), and confidence (Magyar & Duda, 2000). For example, in one well-conducted randomized clinical trial, Cupal and Brewer (2001) examined the effects of imagery and relaxation on knee strength, anxiety, and pain in 30 athletes recovering from anterior cruciate ligament knee reconstruction.

Participants were assigned to either an intervention group that took part in 10 relaxation and guided imagery sessions; a placebo control group that received attention, encouragement, and support but did not participate in imagery and relaxation; or a no-intervention group. Results revealed that compared with participants in the placebo control and no-intervention control groups, those taking part in the relaxation and guided imagery sessions experienced significantly less reinjury anxiety and pain while exhibiting greater knee strength. Thus, using relaxation and imagery during rehabilitation was beneficial both physically and psychologically!

Not only do psychological training and psychological factors affect injury recovery and emotional reactions to injury; they affect adherence to treatment protocols as well (Brewer et al., 2000; Scherzer et al., 2001). Specifically, Brewer and his associates (2000) found that self-motivation was a significant predictor of home exercise compliance, whereas Scherzer and colleagues (2001) discovered that goal setting and positive self-talk were positively related to home rehabilitation exercise completion and program adherence. These are important findings, because the failure to adhere to medical advice (e.g., doing rehabilitation exercises, icing) is a major problem in injury rehabilitation.

Surveys of athletic trainers also support these conclusions (Gordon, Milios, & Grove, 1991; Larson et al., 1996; Ninedek & Kolt, 2000; Wiese, Weiss, & Yukelson, 1991). Larson and his colleagues, for example, asked 482 athletic trainers to identify the primary characteristics of athletes who most or least successfully coped with their injuries. The trainers observed that athletes who more successfully coped with their injuries differed from their less successful counterparts in several ways. They complied better with their rehabilitation and treatment programs; demonstrated a more positive attitude about their injury status and life in general; were more motivated, dedicated, and determined; and asked more questions and became more knowledgeable about their injuries. Some 90% of these trainers also reported that it was important or very important to treat the psychological aspects of injuries.

How Athletes Use Imagery When Recovering from Injury

Researchers Molly Driediger, Craig Hall, and Nichola Galloway (2006) studied imagery use in injured athletes taking part in sport rehabilitation. They discovered that the athletes most often used imagery while observing practices, while driving, and at home in bed. These athletes mainly used imagery during their rehabilitation sessions, as opposed to before or after. They used imagery to rehearse rehabilitation exercises, to improve performance of certain exercises, to facilitate the setting of goals and help facilitate relaxation, to control anxiety, to motivate themselves to engage in their rehabilitation exercises, to help maintain a positive attitude, and maintain concentration. Most interesting was the use of healing imagery to aid in injury recovery and for controlling pain. The findings clearly show that athletes use imagery during their rehabilitation from athletic injuries.

This research makes it clear that psychological factors play an important role in injury recovery. Thus, injury treatment should include psychological techniques to enhance healing and recovery.

Implications for Injury Treatment and Recovery

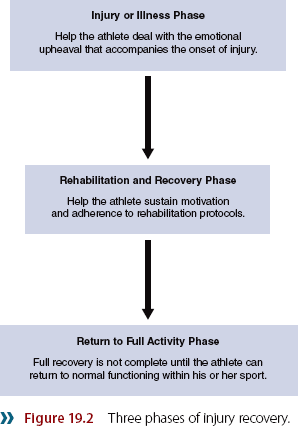

Research on the psychology of athletic injury clearly shows that a holistic approach is to be recommended—one that supplements physical therapy with psychological strategies to facilitate recovery from injuries. The first step in providing such a holistic approach to recovery is to understand the process of psychological rehabilitation and recovery. Figure 19.2 depicts the three phases of injury and injury recovery that Bianco, Malo, and Orlick (1999) identified in their study of seriously injured and ill elite skiers. Each stage poses specific challenges to the athlete and thus often dictates different approaches to the psychology of recovery.

In the initial injury or illness phase, for example, it is best to focus on helping the athlete deal with the emotional upheaval that accompanies the onset of injury. A major source of stress at this initial stage is the uncertainty that accompanies the undiagnosed condition and the implications of any diagnosis, so the clinician should focus on helping the athlete understand the injury. During the rehabilitation and recovery stage, the clinician should focus on helping the athlete sustain motivation and adherence to rehabilitation protocols. Goal setting and maintaining a positive attitude, especially during setbacks, are very important in this regard. Last is the return to full activity; even though an athlete is physically cleared for participation, his recovery is not complete until he can return to normal functioning within his sport. Moreover, recent evidence reveals that after severe injury, return to normal competitive functioning is much harder than often thought and often takes considerable time—from 6 weeks to a year (Bianco et al., 1999; Evans et al., 2000).

Understanding the psychological aspects of injury rehabilitation derives from understanding responses to injury. However, understanding the process of injury response is not enough. Several psychological procedures and techniques facilitate the rehabilitation process, including building rapport with the injured athlete, educating the athlete about the injury and recovery process, teaching specific psychological coping skills, preparing the athlete to cope with setbacks, fostering social support, and learning (and encouraging the athlete to learn) from other injured athletes.

We’ll discuss these in more detail in the following section. It is the sport psychologist’s or trainer’s responsibility to learn and administer these procedures as appropriate.

IDENTIFY ATHLETES AND EXERCISERS WHO ARE AT RISK FOR INJURY

Several studies (Johnson et al., 2005; Maddison & Prapavessis, 2005) have shown that athletes at higher risk of sustaining athletic injuries can be identified. These athletes have been characterized by combinations of high trait anxiety, high life stress, low psychological and coping skills, low social support, and high avoidance coping. Especially promising were the findings that when these athletes at risk of injury took part in stress management training, they lost less time due to injuries and had fewer injuries than at-risk athletes who did not receive such training. Coaches, certified athletic trainers, and fitness personnel should therefore work to identify athletes at high risk for injury.

Build Rapport With the Injured Person

When athletes and exercisers are injured, they often experience disbelief, frustration, anger, confusion, and vulnerability. Such emotions can make it difficult for helpers to establish rapport with the injured person. Empathy is helpful—that is, trying to understand how the injured person feels. Showing emotional support and striving to be there for the injured party also help. Visit, phone, and show your concern for the person. This is especially important after the novelty of the injury has worn off and the exerciser or athlete feels forgotten. In building rapport, do not be overly optimistic about a quick recovery. Instead, be positive and stress a team approach to recovery: “This is a tough break, Mary, and you’ll have to work hard to get through this injury. But I’m in this with you, and together we’ll get you back.”

Educate the Injured Person About the Injury and Recovery Process

Especially when someone is working through a first injury, tell him what to expect during the recovery process. Help him understand the injury in practical terms. For example, if a high school wrestler sustains a clavicular fracture (broken collarbone), you might bring in a green stick and show him what his partial “green stick” break looks like. Explain that he will be out of competition for about 3 months. Equally important, tell him that in 1 month his shoulder will feel much better. Tell him he will likely be tempted to try to resume some normal activities too soon, which might cause a setback.

Outline the specific recovery process. For instance, the certified athletic trainer may indicate that a wrestler can ride an exercise cycle in 2 to 3 weeks, begin range-of-movement exercises in 2 months, and follow this with a weight program until his preinjury strength levels in the affected area have been regained. Then and only then may he return to wrestling, first in drill situations and then slowly progressing back to full contact. (For a comprehensive discussion of the progressive rehabilitation process, see Tippett and Voight’s Functional Progressions for Sport Rehabilitation, 1995.)

Teach Specific Psychological Coping Skills

The most important psychological skills to learn for rehabilitation are goal setting, positive self-talk, imagery or visualization, and relaxation training (Hardy & Crace, 1990; Petitpas & Danish, 1995; Wiese & Weiss, 1987).

Goal setting can be especially useful for athletes rehabilitating from injury. For example, Theodorakis, Malliou, Papaioannou, Beneca, and Filactakidou (1996) found that setting personal performance goals with knee-injured participants facilitated performance, just as it did with uninjured individuals. They concluded that, combined with strategies designed to enhance self-efficacy, personal performance goals can be especially helpful in decreasing an athlete’s recovery time. Some goal-setting strategies to use with injured athletes and exercisers are setting a date to return to competition; determining the number of times per week to come to the training room for therapy; and deciding the number of range-of-motion, strength, and endurance exercises to do during recovery sessions. Highly motivated athletes tend to do more than is required during therapy, and they can reinjure themselves by overdoing it. Emphasize the need to stick to goal plans and not do more when they feel better on a given day.

Self-talk strategies help counteract the lowered confidence that can follow injury. Athletes should learn to stop their negative thoughts (“I am never going to get better”) and replace them with realistic, positive ones (“I’m feeling down today, but I’m still on target with my rehabilitation plan—I just need to be patient and I’ll make it back”).

Visualization is useful in several ways during rehabilitation. An injured player can visualize herself in game conditions to maintain her playing skills and facilitate her return to competition. Or someone might use imagery to quicken recovery, visualizing the removal of injured tissue and the growth of new healthy tissue and muscle. This may sound far-fetched, but the use of healing imagery often characterizes fast-healing patients (see study on healing from knee injury; Ievleva & Orlick, 1991). Finally, Sordoni, Hall, and Forwell (2000) found that athletes who use imagery in sport do not automatically use it to the same degree when they are injured. Thus, those assisting in injury rehabilitation need to encourage athletes to use imagery during rehabilitation just as they do when participating in their sport.

Relaxation training can be useful to relieve pain and stress, which usually accompany severe injury and the injury recovery process. Athletes can also use relaxation techniques to facilitate sleep and reduce general levels of tension.

Teach How to Cope With Setbacks

Injury rehabilitation is not a precise science. People recover at different rates, and setbacks are not uncommon. Thus, an injured person must learn to cope with setbacks. Inform the athlete during the rapport stage that setbacks will likely occur. At the same time, encourage the person to maintain a positive attitude toward recovery. Setbacks are normal and not a cause for panic, so there’s no reason to be discouraged. Similarly, rehabilitation goals need to be evaluated and periodically redefined. To help teach people coping skills, encourage them to inform significant others when they experience setbacks. By discussing their feelings, they can receive the necessary social support.

Foster Social Support

Social support of injured athletes can take many forms, including emotional support from friends and loved ones; informational support from a coach, in the form of statements such as “You’re on the right track”; and even tangible support, such as money from parents (Hardy & Crace, 1991). Research (Bianco, 2001; Green & Weinberg, 2001) has shown that social support is critical for injured athletes. They need to know that their coaches and teammates care, to feel confident that people will listen to their concerns without judging them, and to learn how others have recovered from similar injuries.

It is a mistake to assume that adequate social support occurs automatically. As previously noted, social support tends to be more available immediately after an injury and to become less available during the later stages of recovery. Remember that injured people benefit from receiving adequate social support throughout the recovery process. In providing social support, consider these guidelines and recommendations:

Social support serves as a resource that facilitates coping. It can help reduce stress, enhance mood, increase motivation for rehabilitation, and improve treatment adherence. Thus, efforts must be made to provide social support to injured athletes. Medical personnel should receive training in the provision of social support, and efforts should be made to involve and inform coaches and significant others about how they might socially support the injured athlete.

Social support serves as a resource that facilitates coping. It can help reduce stress, enhance mood, increase motivation for rehabilitation, and improve treatment adherence. Thus, efforts must be made to provide social support to injured athletes. Medical personnel should receive training in the provision of social support, and efforts should be made to involve and inform coaches and significant others about how they might socially support the injured athlete.

In general, athletes turn to coaches and medical professionals for informational support and to family and friends for emotional support. Athletes are less likely to seek support from persons who have not been helpful in the past or who do not seem committed to their relationship. Finally, people with low self-esteem are less likely than others to seek social support (Bianco & Eklund, 2001).

In general, athletes turn to coaches and medical professionals for informational support and to family and friends for emotional support. Athletes are less likely to seek support from persons who have not been helpful in the past or who do not seem committed to their relationship. Finally, people with low self-esteem are less likely than others to seek social support (Bianco & Eklund, 2001).

Recognize that the type of social support an athlete needs varies across rehabilitation phases and support sources (Bianco, 2001). For example, in the injury or illness phase, informational social support is critical so that the athlete clearly understands the nature of the injury. Knowledgeable sports medicine personnel who are able to explain injuries in terms that athletes understand are critical in this regard. However, in the recovery stage, athletes may need a coach to help challenge them and motivate them to adhere to their rehabilitation plan.

Recognize that the type of social support an athlete needs varies across rehabilitation phases and support sources (Bianco, 2001). For example, in the injury or illness phase, informational social support is critical so that the athlete clearly understands the nature of the injury. Knowledgeable sports medicine personnel who are able to explain injuries in terms that athletes understand are critical in this regard. However, in the recovery stage, athletes may need a coach to help challenge them and motivate them to adhere to their rehabilitation plan.

The need for social support is greatest when the rehabilitation process is slow, when setbacks occur, or when other life demands place additional stress on athletes (Evans et al., 2000).

The need for social support is greatest when the rehabilitation process is slow, when setbacks occur, or when other life demands place additional stress on athletes (Evans et al., 2000).

Although generally helpful, social support can have negative effects on injured athletes. This occurs in cases in which the support provider does not have a good relationship with the athlete, lacks credibility in the athlete’s eyes, or forces support on the athlete. Athletes view social support as beneficial when the type of social support matches their needs and conveys positive information toward them (Bianco, 2001).

Although generally helpful, social support can have negative effects on injured athletes. This occurs in cases in which the support provider does not have a good relationship with the athlete, lacks credibility in the athlete’s eyes, or forces support on the athlete. Athletes view social support as beneficial when the type of social support matches their needs and conveys positive information toward them (Bianco, 2001).

Learn From Injured Athletes

Another good way to help injured athletes and exercisers cope with injury is to heed recommendations that injured athletes have made. Members of a U.S. ski team who sustained season-ending injuries made several suggestions for injured athletes, the coaches working with them, and sports medicine providers (Gould, Udry, Bridges, & Beck, 1996, 1997a). These are summarized in “Elite Skiers’ Recommendations for Coping With Season-Ending Injuries and Facilitating Rehabilitation,” and they should be considered both by injured athletes and by those assisting them.

Elite Skiers’ Recommendations for Coping With Season-Ending Injuries and Facilitating Rehabilitation

Members of a U.S. ski team who sustained season-ending injuries offered the following recommendations for other injured athletes, coaches, and sports medicine personnel.

Recommendations for Other Injured Athletes

Read one’s body and pace oneself accordingly.

Read one’s body and pace oneself accordingly.

Accept and positively deal with the situation.

Accept and positively deal with the situation.

Focus on quality training.

Focus on quality training.

Find and use medical resources.

Find and use medical resources.

Use social resources wisely.

Use social resources wisely.

Set goals.

Set goals.

Feel confident with medical staff coaches.

Feel confident with medical staff coaches.

Work on mental skills training.

Work on mental skills training.

Use imagery and visualization.

Use imagery and visualization.

Initiate and maintain a competitive atmosphere and involvement.

Initiate and maintain a competitive atmosphere and involvement.

Recommendations for Coaches

Foster coach–athlete contact and involvement.

Foster coach–athlete contact and involvement.

Demonstrate positive empathy and support.

Demonstrate positive empathy and support.

Understand individual variations in injuries and injury emotions.

Understand individual variations in injuries and injury emotions.

Motivate by optimally pushing.

Motivate by optimally pushing.

Engineer training environment for high-quality, individualized training.

Engineer training environment for high-quality, individualized training.

Have patience and realistic expectations.

Have patience and realistic expectations.

Don’t repeatedly mention injury in training.

Don’t repeatedly mention injury in training.

Recommendations for Sports Medicine Personnel

Educate and inform athlete of injury and rehabilitation.

Educate and inform athlete of injury and rehabilitation.

Use appropriate motivation and optimally push.

Use appropriate motivation and optimally push.

Demonstrate empathy and support.

Demonstrate empathy and support.

Have supportive personality (be warm, open, and not overly confident).

Have supportive personality (be warm, open, and not overly confident).

Foster positive interaction and customize training.

Foster positive interaction and customize training.

Demonstrate competence and confidence.

Demonstrate competence and confidence.

Encourage the athlete’s confidence.

Encourage the athlete’s confidence.

Learning Aids

Summary

1. Discuss the role of psychological factors in athletic and exercise injuries.

Psychological factors influence the incidence of injury, responses to injury, and injury recovery. Professionals in our field must be prepared to initiate teaching and coaching practices that help prevent injuries, assist in the process of coping with injury, and provide supportive psychological environments to facilitate injury recovery.

2. Identify psychological antecedents that may predispose people to athletic injuries.

Psychological factors, including stress and certain attitudes, can predispose athletes and exercisers to injuries. Professional sport and exercise science personnel must recognize antecedent conditions, especially major life stressors, in individuals who have poor coping skills and little social support.

3. Compare and contrast explanations for the stress–injury relationship.

When high levels of stress are identified, stress management procedures should be implemented and training regimens adjusted. Athletes must learn to distinguish between the normal discomfort of training and the pain of injury. They should understand that a “no pain, no gain” attitude can predispose them to injury.

4. Describe typical psychological reactions to injuries.

Injured athletes and exercisers exhibit various psychological reactions, typically falling into three categories: injury-relevant information processing, emotional upheaval and reactive behavior, and positive outlook and coping. Increased fear and anxiety, lowered confidence, and performance decrements also commonly occur in injured athletes.

5. Identify signs of poor adjustment to injury.

If you work with an injured athlete or exerciser, be vigilant in monitoring warning signs of poor adjustment to an injury. These include feelings of anger and confusion, obsession with the question of when one can return to play, denial (e.g., “The injury is no big deal”), repeatedly coming back too soon and experiencing reinjury, exaggerated bragging about accomplishments, dwelling on minor physical complaints, guilt about letting the team down, withdrawal from significant others, rapid mood swings, and statements indicating that no matter what is done, recovery will not occur.

6. Explain how to implement psychological skills and strategies that can speed the rehabilitation process.

Psychological skills training has been shown to facilitate the rehabilitation process. Psychological foundations of injury rehabilitation include identifying athletes who are at high risk of injury; building rapport with the injured individual; educating the athlete about the nature of the injury and the injury recovery process; teaching specific psychological coping skills, such as goal setting, relaxation techniques, and imagery; preparing the person to cope with setbacks in rehabilitation; and fostering social support. Athletes themselves have also made specific recommendations for coping with injury that are useful for other injured athletes, coaches, and sports medicine providers.

Key Terms

social support

grief response

Review Questions

1. What is the Andersen and Williams (1988) stress–injury relationship model? Why is it important?

2. What three categories of psychological factors are related to the occurrence of athletic and exercise injuries?

3. Identify two explanations for the stress–injury relationship.

4. Describe three general categories of emotional reactions to athletic injuries.

5. What are common symptoms of poor adjustment to athletic and exercise injuries?

6. What strategies did Ievleva and Orlick (1991) find associated with enhanced healing in knee-injured athletes? Why are these findings important?

7. Describe the role of social support in athletic injury rehabilitation.

8. Give six implications for working with exercisers and athletes during injury treatment and recovery, briefly identifying and describing each.

9. Discuss how stress management could be used for the prevention of injury.

Critical Thinking Questions

1. A close friend sustains a major knee injury and needs surgery. What have you learned that can help you prepare your friend for surgery and recovery?

2. Design a persuasive speech to convince a sports medicine center to hire a sport psychology specialist. How would you convince the center’s directors that patients or clients would benefit?