After reading this chapter, you should be able to

1. describe what makes up personality and why it is important,

2. discuss major approaches to understanding personality,

3. identify how personality can be measured,

4. assess personality tests and research for practicality and validity,

5. understand the relationship between personality and behavior in sport and exercise,

6. describe how cognitive strategies relate to athletic success, and

7. apply what you know of personality in sport and exercise settings to better understand people’s personalities.

Thousands of articles have been published on aspects of sport personality (Ruffer, 1976a, 1976b; Vealey, 1989, 2002), many of them written during the 1960s and 1970s. This voluminous research demonstrates how important researchers and practitioners consider the role of personality to be in sport and exercise settings. Researchers have asked, for example, what causes some students to be excited about physical education classes, whereas others don’t even bother to “dress out.” Researchers have questioned why some exercisers stay with their fitness program whereas others lose motivation and drop out, whether personality tests should be used to select athletes for teams, and whether athletic success can be predicted by an athlete’s personality

type.

Defining Personality

Have you ever tried to describe your own personality? If you have, you probably found yourself listing adjectives like funny, outgoing, happy, or stable. Maybe you remembered how you reacted in various situations. Is there more to personality than these kinds of attributes? Many theorists have attempted to define personality, and they agree on one aspect: uniqueness. In essence, personality refers to the characteristics—or blend of characteristics—that make a person unique. One of the best ways to understand personality is through its structure. Think of personality as divided into three separate but related levels (see figure 2.1): a psychological core, typical responses, and role-related behavior (Hollander, 1967; Martens, 1975).

Psychological Core

The most basic level of your personality is called the psychological core. The deepest component, it includes your attitudes and values, interests and motives, and beliefs about yourself and your self-worth. In essence, the psychological core represents the centerpiece of your personality and is “the real you,” not who you want others to think you are. For example, your basic values might revolve around the importance of family, friends, and religion in your life.

Typical Responses

Typical responses are the ways we each learn to adjust to the environment or how we usually respond to the world around us. For example, you might be happy-go-lucky, shy, and even-tempered. Often your typical responses are good indicators of your psychological core. That is, if you consistently respond to social situations by being quiet and shy, you are likely to be introverted, not extroverted. However, if someone observed you being quiet at a party and from that evidence alone concluded that you were introverted, that person could well be mistaken—it may have been the particular party situation that caused you to be quiet. Your quietness may not have been a typical response.

Role-Related Behavior

How you act based on what you perceive your social situation to be is called role-related behavior. This behavior is the most changeable aspect of personality: Your behavior changes as your perceptions of the environment change. Different situations require playing different roles. You might, on the same day, play the roles of student at a university, coach of a Little League team, employee, and friend. Likely you’ll behave differently in each of these situations; for example, you’ll probably exert more leadership as a coach than as a student or employee. Roles can conflict with each other. For example, a parent who is coaching her child’s soccer team might feel a conflict between her coaching and parenting roles.

Understanding Personality Structure

As you saw in figure 2.1, the three levels of personality encompass a continuum from internally driven to externally driven behaviors. To simplify this, compare your levels of personality to a chocolate-covered cherry. Everyone sees the outside wrapper (role-related behavior); those who go to the trouble to take off the wrapper see the chocolate layer (typical responses); and only the people interested or motivated enough to bite into the candy see the cherry center (psychological core).

The psychological core is not only the most internal of the three levels and the hardest to get to know; it is also the most stable part of your personality. It remains fairly constant over time. On the other end of the continuum are the most external, role-related behaviors, which are subject to the greatest influence from the external social environment. For example, you might always tell the truth because being truthful is one of your core values. But your behavior might vary in some areas, such as being aloof in your role as a fitness director and affectionate in your role as a parent. Usually your responses lie somewhere in between, however, because they result from the interaction of your psychological core and role-related behaviors.

Both stability and change are desirable in personality. The core, or stable, aspect of personality provides the structure we need to function effectively in society, whereas the dynamic, or changing, aspect allows for learning.

As coaches, physical educators, certified athletic trainers, and exercise leaders, we can be more effective when we understand the different levels of personality structure that lie beyond the role-related behaviors particular to a situation. Getting to know the real person (i.e., the psychological core) and that person’s typical modes of response produces insight into the individual’s motivations, actions, and behavior. In essence, we need to know what makes people tick to choose the best way to help them. Especially when we work long-term with people, such as over a season or more, it’s helpful to understand more about their individual core values (i.e., psychological core).

Studying Personality From Five Viewpoints

Psychologists have looked at personality from several viewpoints. Five of their major ways of studying personality in sport and exercise have been called the psychodynamic, trait, situation, interactional, and phenomenological approaches.

Psychodynamic Approach

Popularized by Sigmund Freud and neo-Freudians such as Carl Jung and Eric Erickson, the psychodynamic approach to personality is characterized by two themes (Cox, 1998). First, it places emphasis on unconscious determinants of behavior, such as what Freud called the id, or instinctive drives, and how these conflict with the more conscious aspects of personality, such as the superego (one’s moral conscience) or the ego (the conscious personality). Second, this approach focuses on understanding the person as a whole rather than identifying isolated traits or dispositions.

The psychodynamic approach is complex; it views personality as a dynamic set of processes that are constantly changing and often in conflict with one another (Vealey, 2002). For example, those taking a psychodynamic approach to the study of personality might discuss how unconscious aggressive instincts conflict with other aspects of personality, such as one’s superego, to determine behavior. Special emphasis is placed on how adult personality is shaped by the resolution of conflicts between unconscious forces and the values and conscience of the superego in childhood.

Although the psychodynamic approach has had a major impact on the field of psychology, especially clinical approaches to psychology, it has had little impact on sport psychology. Swedish sport psychologist Erwin Apitzsch (1995) has urged North Americans to give more attention to this approach, however, pointing out the support that it receives in non-English studies of its value in sport. Apitzsch has measured defense mechanisms in athletes and used this information to help performers better cope with stress and anxiety. Specifically, he contends that athletes often feel threatened and that they react with anxiety. As a defense against their anxiety, athletes display various unconscious defense mechanisms, such as maladaptive repression (the athletes freeze or become paralyzed during play) or denial of the problem. When inappropriate defense mechanisms are used, the athletes’ performance and satisfaction are affected. Through psychotherapy, however, athletes can learn to effectively deal with these problems.

Strean and Strean (1998) and Conroy and Benjamin (2001) heeded Apitzsch’s call to give more attention to the psychodynamic approach. Besides overviewing the approach, Strean and Strean (1998) discussed how psychodynamic concepts (e.g., resistance) can be used to explain athlete behavior—not just maladaptive functioning of athletes, but normal personality as well. Moreover, Conroy and Benjamin (2001) discussed and presented examples of the use of a structural analysis of social behavior method to measure psychodynamic constructs through case study research. This is important, because a major weakness of the psychodynamic approach has been the difficulty of testing it.

Another weakness of the psychodynamic approach is that it focuses almost entirely on internal determinants of behavior, giving little attention to the social environment. For this reason, many contemporary sport psychology specialists do not adopt the psychodynamic approach. Moreover, it is unlikely that most sport psychology specialists, especially those trained in educational sport psychology, will become qualified to use a psychodynamic approach. However, Giges (1998) indicated that although specialized training is certainly needed to use the psychodynamic approach in a therapeutic manner, an understanding of its key concepts can help us understand athletes and their feelings, thoughts, and behaviors.

Finally, the key contribution of this approach is the recognition that not all the behaviors of an exerciser or athlete are under conscious control and that at times it may be appropriate to focus on unconscious determinants of behavior. For example, a world-class aerial skier experienced a particularly bad crash; when he recovered, he could not explain his inability to execute the complex skill he was injured on. He said that in the middle of executing the skill he would freeze up, “like a deer caught in headlights.” Moreover, extensive cognitive–behavioral psychological strategies (described later in this chapter), which have been successfully used with other skiers, did not help him. The athlete eventually was referred to a clinical psychologist who took a more psychodynamic approach to the problem and had more success.

Trait Approach

The trait approach assumes that the fundamental units of personality—its traits—are relatively stable. That is, personality traits are enduring and consistent across a variety of situations. Taking the trait approach, psychologists consider that the causes of behavior generally reside within the person and that the role of situational or environmental factors is minimal. Traits are considered to predispose a person to act a certain way, regardless of the situation or circumstances. If an athlete is competitive, for example, he will be predisposed to playing hard and giving all, regardless of the situation or score. But at the same time, a predisposition does not mean that the athlete will always act this way; it simply means that the athlete is likely to be competitive in sport situations.

The most noted of the trait proponents in the 1960s and 1970s included Gordon Allport, Raymond Cattell, and Hans Eysenck. Cattell (1965) developed a personality inventory with 16 independent personality factors (16 PF) that he believed describe a person. Eysenck and Eysenck (1968) viewed traits as relative, the two most significant traits ranging on continuums from introversion to extroversion and from stability to emotionality. Today, the “Big 5” model of personality is most widely accepted (Gill & Williams, 2008; Vealey, 2002). This model contends that five major dimensions of personality exist, including neuroticism (nervousness, anxiety, depression, and anger) vs. emotional stability; extraversion (enthusiasm, sociability, assertiveness, and high activity level) vs. introversion; openness to experience (originality, need for variety, curiosity); agreeableness (amiability, altruism, modesty); and conscientiousness (constraint, achievement striving, self-discipline). These five dimensions have been found to be the most important general personality characteristics that exist across individuals, with most other more specific personality characteristics falling within the dimensions (McRae & John, 1992). Moreover, it is hypothesized that individuals possessing different levels of these characteristics will behave differently. For example, people high in conscientiousness would be more motivated toward order, self-discipline, and dutifulness, whereas those high on neuroticism would generally be vulnerable and self-conscious. The Big 5 model of personality has been shown to be of some use in understanding why different exercise interventions are appropriate for people with different personality characteristics (Rhodes, Courneya, & Hayduk, 2002). A meta-analysis or statistical review of 35 independent studies also showed that the personality traits of extraversion and conscientiousness positively correlated with physical activity levels while neuroticism was negatively related to physical activity (Rhodes & Smith, 2006). Researchers have also begun to test the Big 5 model of personality in sport (Piedmont, Hill, & Blanco, 1999; Wann, Dunham, Byrd, & Keenan, 2004). Wann and colleagues (2004), for example, studied sports fans, finding that identifying with a local team (and receiving social support from others) was positively related to psychological well-being as measured by the Big 5 subscales of extroversion, openness, and conscientiousness.

Regardless of the particular view and measure endorsed, trait theorists argue that the best way to understand personality is by considering traits that are relatively enduring and stable over time. However, simply knowing an individual’s personality traits will not always help us predict how that person will behave in a particular situation. For example, some people anger easily during sport activity, whereas others seldom get angry. Yet the individuals who tend to get angry in sport may not necessarily become angry in other situations. So simply knowing an individual’s personality traits does not necessarily predict whether she will act on them. The predisposition toward anger does not tell you what specific situations will provoke that response. This observation led some researchers to study personality by focusing on the situation or environment that might trigger behaviors, rather than on personality traits.

The Paradox of Perfectionism

Perfectionism has been one of the most widely studied personality characteristics in sport psychology in recent years. It is a personality style characterized by the setting of extremely high standards of performance, striving for flawlessness, and a tendency to be overly critical in evaluating one’s performance (Flett & Hewitt, 2005). It is a multidimensional construct that consists of various components like setting high standards, concern over mistakes, and being highly organized. The multidimensional nature of perfectionism has led to some very interesting findings. Maladaptive perfectionism (a focus on high standards accompanied by a concern over mistakes and evaluation by others) has been found to be associated with excessive exercise (e.g., Flett, Pole-Langdon, & Hewitt, 2003; Flett & Hewittt, 2005), poor performance (Stoeber, Uphill, & Hotham, 2009), and athlete burnout (Appleton, Hall, & Hill, 2009). However, adaptive perfectionism (focusing on high standards but not excessively worrying about making mistakes or about how others evaluate one’s performance) has been found to be associated with better learning and performance (Stoeber et al., 2009) and more adaptive goal patterns (e.g., Stoll, Lau, & Stoeber, 2008). Thus, depending on the specific components characterizing one’s perfectionistic personality, perfectionism can lead to both highly positive and extremely negative consequences. Other interesting findings derived from sport psychological perfectionism literature include the following:

Situation Approach

The situation approach argues that behavior is determined largely by the situation or environment. It draws from social learning theory (Bandura, 1977a), which explains behavior in terms of observational learning (modeling) and social reinforcement (feedback). This approach holds that environmental influences and reinforcements shape the way you behave. You might act confident, for instance, in one situation but tentative in another, regardless of your particular personality traits. Furthermore, if the influence of the environment is strong enough, the effect of personality traits will be minimal. For example, if you are introverted and shy, you still might act assertively or even aggressively if you see someone getting mugged. Many football players are gentle and shy off the field, but the game (the situation) requires them to act aggressively. Thus, the situation would be a more important determinant of their behavior than their particular personality traits would be.

Although the situation approach is not as widely embraced by sport psychologists as the trait approach, Martin and Lumsden (1987) contended that you can influence behavior in sport and physical education by changing the reinforcements in the environment. Still, the situation approach, like the trait approach, cannot truly predict behavior. A situation can certainly influence some people’s behavior, but other people will not be swayed by the same situation.

Interactional Approach

The interactional approach considers the situation and person as codeterminants of behavior—that is, as variables that together determine behavior. In other words, knowing both an individual’s psychological traits and the particular situation is helpful in understanding behavior. Not only do personal traits and situational factors independently determine behavior, but at times they interact or mix with each other in unique ways to influence behavior. For example, a person with a high hostility trait won’t necessarily be violent in all situations (e.g., as a frustrated spectator at a football game in the presence of his mother). However, when the hostile person is placed in the right potentially violent situation (e.g., as a frustrated spectator at a football game with his roughneck friends), his violent nature might be triggered. In that particular situation, violence might result (e.g., he hits an opponent-team fan who boos his favorite player).

Researchers using an interactional approach ask these kinds of questions:

The vast majority of contemporary sport and exercise psychologists favor the interactional approach to studying behavior. Bowers (1973) found that the interaction between persons and situations could explain twice as many behaviors as traits or situations alone. The interactional approach requires investigating how people react individually in particular sport and physical activity settings.

For example, Fisher and Zwart (1982) studied the anxiety that athletes showed in different basketball situations—before, during, and after the game (e.g., “The crowd is very loud and is directing most of its comments toward you; you have just made a bad play and your coach is criticizing you”). Given these situations, the athletes were asked to report to what degree they would react (e.g., get an uneasy feeling, enjoy the challenge). Results revealed that the athletes’ reactions to each basketball situation were colored by their particular mental and emotional makeup. Thus, Jeff, who is usually anxious and uptight, may “choke” before shooting free throws with a tied score, whereas Pat, who is laid back and less anxious, might enjoy the challenge. How would you react?

![]()

Interactional Approach to a Case of Low Self-Esteem

Two women enroll in an exercise class. Maureen has high self-esteem, and Cher has low self-esteem. The class is structured so that each participant takes a turn leading the exercises. Because she is confident in social situations and about how she looks, Maureen really looks forward to leading the class. She really likes being in front of the group, and after leading the class several times she has even given thought to becoming an instructor. Cher, on the other hand, is not confident about getting up in front of people and feels embarrassed by how she looks. Unlike Maureen, Cher finds it anxiety provoking to lead class. All she can think about are the negative reactions the class members must be having while watching her. Although she really likes to exercise, there is no way she wants to be put in the situation of having to get up in front of class again. Not surprisingly, Cher loses interest in the class and drops out.

Phenomenological Approach

Although most contemporary sport and exercise psychologists adopt an interactional approach to the study of personality, the phenomenological approach is the most popular orientation taken today (Vealey, 2002). Like the interactional view, the phenomenological approach contends that behavior is best determined by accounting for both situations and personal characteristics. However, instead of focusing on fixed traits or dispositions as the primary determinants of behavior, the psychologist examines the person’s understanding and interpretation of herself and her environment. Hence, an individual’s subjective experiences and personal views of the world and of herself are seen as critical.

Many of the most prominent contemporary theories used in sport psychology fall within the phenomenological framework. For example, self-determination theories of motivation like cognitive evaluation theory (discussed in chapter 6), achievement goal theory (discussed in chapter 3), social cognitive theories like Bandura’s self-efficacy (discussed in chapter 14), and much of the recent research focusing on cognitive characteristics associated with athletic success (discussed later in this chapter) fall within the phenomenological approach.

In summary, these five approaches or viewpoints to understanding personality differ in several important ways. First, they vary along a continuum (see figure 2.2) of behavioral determination ranging from the view that behavior is determined by a person’s internal characteristics (e.g., psychodynamic theories) to the view that behavior is determined by the situation or environment (e.g., situation approach). Second, they vary greatly in terms of assumptions about the origins of human behavior—whether behavior is determined by fixed traits or by conscious or subconscious determinants and how important a person’s active interpretation of himself and his environment is. Although all these viewpoints have played an important role in advancing our understanding of personality in sport and physical activity, the interactional and phenomenological views are most often stressed today and form the basis of much of this text.

Measuring Personality

When research is conducted appropriately, it can shed considerable light on how personality affects behavior in sport and exercise settings. Psychologists have developed ways to measure personality that can help us understand personality traits and states. Many psychologists distinguish between an individual’s typical style of behaving (traits) and the situation’s effects on behavior (states). This distinction between psychological traits and states has been critical in the development of personality research in sport. However, even though a given psychological trait predisposes someone to behave in a certain way, the behavior doesn’t necessarily occur in all situations. Therefore, you should consider both traits and states as you attempt to understand and predict behavior.

Trait and State Measures

Look at the sample questions from trait and state measures of confidence (Vealey, 1986). They highlight the differences between trait and state measures of confidence in a sport context. The Trait Sport Confidence Inventory asks you to indicate how you “generally” or typically feel, whereas the State Sport Confidence Inventory asks you to indicate how you feel “right now,” at a particular moment in time in a particular situation.

Situation-Specific Measures

Although general scales provide some useful information about personality traits and states, situation-specific measures predict behavior more reliably for given situations because they consider both the personality of the participant and the specific situation (interactional approach). For example, Sarason observed in 1975 that some students did poorly on tests when they became overly anxious. These students were not particularly anxious in other situations, but taking exams made them freeze up. Sarason devised a situationally specific scale to measure how anxious a person usually feels before taking exams (i.e., test anxiety). This situation-specific scale could predict anxiety right before exams (state anxiety) better than a general test of trait anxiety could.

Sport-Specific Measures

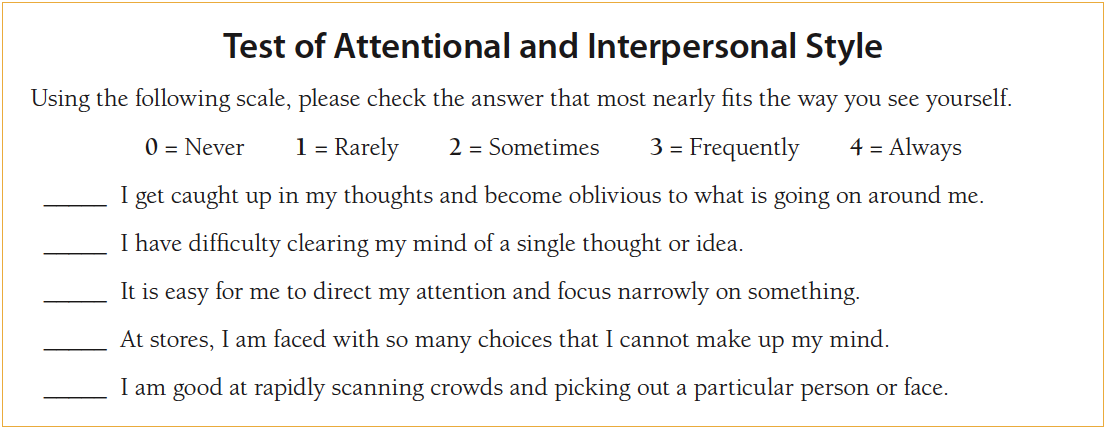

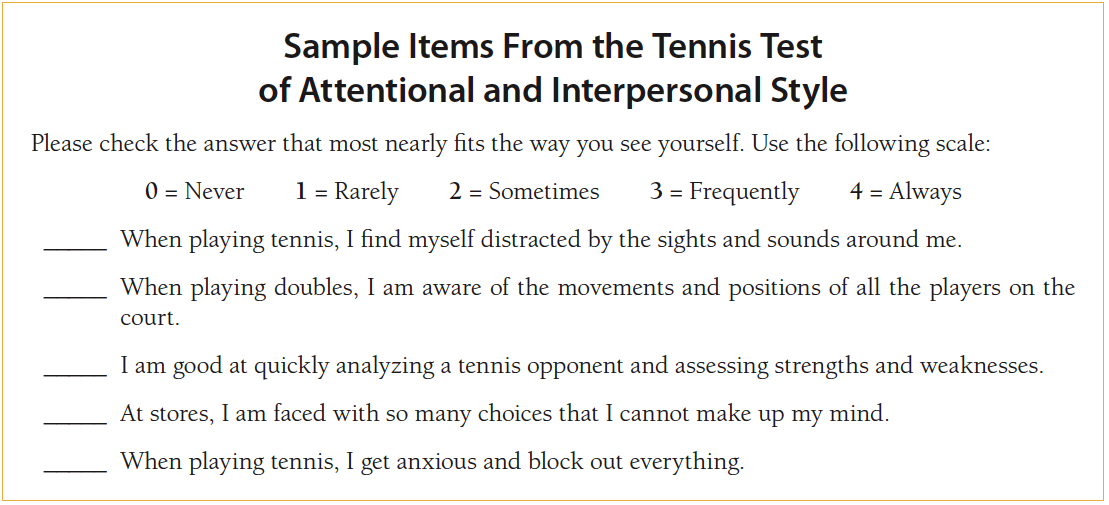

Now look at some of the questions and response formats from the “Test of Attentional and Interpersonal Style” (Nideffer, 1976b) and the “Profile of Mood States” (McNair, Lorr, & Droppleman, 1971) on page 36. Notice that the questions do not directly relate to sport or physical activity. Rather, they are general and more about overall attentional styles and

mood.

Until recently, almost all of the trait and state measures of personality in sport psychology came from general psychological inventories, without specific reference to sport or physical activity. Sport-specific tests provide more reliable and valid measures of personality traits and states in sport and exercise contexts. For example, rather than test how anxious you are before giving a speech or going out on a date, a coach might test how anxious you are before a competition (especially if excess anxiety proves

detrimental to your performance). A sport-specific test of anxiety assesses precompetitive anxiety better than a general anxiety test does. Psychological inventories developed specifically for use in sport and physical activity settings include

Some tests have been developed even for particular sports. These inventories can help identify a person’s areas of psychological strength and weakness in that sport or physical activity. After gathering the results, a coach can advise players on how to build on their strengths and reduce or eliminate their weaknesses. An example of a sport-specific test is the Tennis Test of Attentional and Interpersonal Style (Van Schoyck & Grasha, 1981).

Fluctuations Before and During Competition

Feelings change before and during a competition. Usually states are assessed shortly before (within 30 minutes of) the onset of a competition or physical activity. Although a measurement can indicate how someone is feeling at that moment, these feelings might change during the competition. For example, Matt’s competitive state anxiety 30 minutes before playing a championship football game might be very high. But once he “takes a few good hits” and gets into the flow of the game, his anxiety might drop to a moderate level. In the fourth quarter, Matt’s anxiety might increase again when the score is tied. We need to consider such fluctuations in evaluating personality and reactions to competitive settings.

Consider Traits and States to Understand Behavior

Terry is a confident person in general; he usually responds to situations with higher confidence than Tim, who is low trait-confident. As a coach you are interested in how confidence relates to performance, and you want to know how Tim and Terry are feeling immediately before a swimming race. Although Tim is not confident in general, he swam on his high school swim team and is confident of his swimming abilities. Consequently, his state of confidence right before the race is high. Conversely, although Terry is highly confident in general, he has had little swimming experience and is not even sure he can finish the race. Thus, his state confidence is low right before the race. If you measured only Tim’s and Terry’s trait confidence, you would be unable to predict how confident they feel before swimming. On the other hand, if you observed Tim’s and Terry’s state confidence in a different sport—baseball, for example—their results might be different.

This example demonstrates the need to consider both trait and state measures to investigate personality. State and trait levels alone are less significant than the difference between a person’s current state level and trait level. This difference in scores represents the impact of situation factors on behavior. Terry’s and Tim’s state anxiety levels differed because of experience in swimming (a situational factor).

Using Psychological Measures

The knowledge of personality is critical to success as a coach, teacher, or exercise leader. You may betempted to use psychological tests to gather information about the people whom you want to help professionally. Bear in mind, however, that psychological inventories alone cannot actually predict athletic success. And they have sometimes been used unethically—or at least inappropriately—and administered poorly. Indeed, it isn’t always clear how psychological inventories should be used! Yet it is essential that professionals understand the limitations and the uses and abuses of testing in order to know what to do and what not to do.

You want to be able to make an informed decision—that is, to be an informed consumer—on how (or whether) to use personality tests. These are some important questions to consider about psychological testing:

In 1985, the American Psychological Association provided seven helpful guidelines on the use of psychological tests, which we explain briefly in the following sections.

Know the Principles of Testing and Measurement Error

Before you administer and interpret psychological inventories, you should understand testing principles, be able to recognize measurement errors, and have well-designed and validated measures. Not all psychological tests have been systematically developed and made reliable. Making predictions or drawing inferences about an athlete’s or exerciser’s behavior and personality structure on the basis of these tests would be misleading and unethical. Test results are not absolute or irrefutable.

Even valid tests that have been reliably developed may have measurement errors. Suppose you wish to measure self-esteem in 13- to 15-year-old physical education students. You choose a good test developed for adults, inasmuch as there are no tests specifically for youngsters. If the students do not fully understand the questions, however, the results will not be reliable. Similarly, if you give a test developed on a predominantly white population to African American and Hispanic athletes, the results might be less reliable because of cultural differences. In these situations, a researcher should conduct pilot testing with the specific population to establish the reliability and validity of the test instrument.

People usually want to present themselves in a favorable light. Sometimes they answer questions in what they think is a socially desirable way, a response style known as “faking good.” For example, an athlete may fear letting her coach know how nervous she gets before competition, so she skews her answers in a precompetitive anxiety test, trying to appear calm, cool, and collected.

Know Your Limitations

The American Psychological Association recommends that people administering tests be aware of the limitations of their training and preparation. However, some people do not recognize the limits of their knowledge, or they use and interpret test results unethically, which can be damaging to the athletes. For instance, it is inappropriate to use personality inventories developed to measure psychopathology (abnormality, such as schizophrenia or manic depression) to measure a more normal increase in anxiety. Furthermore, it is inappropriate to give physical education students a clinical personality test.

Do Not Use Psychological Tests for Team Selection

Using only psychological tests to select players for a team is an abuse because the tests are not accurate enough to be predictive. For example, determining if an athlete has the “right” psychological profile to be a middle linebacker in football or a point guard in basketball on the basis of psychological tests alone is unfair. Some psychological tests may have a limited use, but they must be considered in conjunction with physical performance measures, coach evaluations, and the actual levels of play.

Using personality inventories alone to select athletes for a team or to cut them from a team is an abuse of testing that should not be tolerated. When psychological tests are used as part of a battery of measures to help in the athlete selection process, three key conditions should always be kept in mind (Singer, 1988). First, the particular test must be a valid and reliable measure. Second, the user must know what personality characteristics are key for success in the sport of interest and the ideal levels of those characteristics needed. Third, the user should know how much athletes can compensate in some characteristics for the lack of others.

Include Explanation and Feedback

Before they actually complete tests, athletes, students, and exercisers should be told the purpose of the tests, what they measure, and how a test is going to be used. Athletes should receive specific feedback about the results to allow them to gain insight into themselves from the testing process.

Assure Athletes of Confidentiality

It is essential to assure people that their answers will remain confidential in whatever tests they take (and to ensure that this confidentiality is maintained!). With this assurance, test takers are more likely to answer truthfully. When they fear exposure, they may fake or falsify their answers, which can distort the findings and make interpretation virtually useless. Students in a physical education class might wonder if a test will affect their grades, and in these circumstances they are more likely to exaggerate their strengths and minimize their weaknesses. If you do not explain the reasons for testing, test takers typically become suspicious and wonder if the coach will use the test to help select starters or weed out players.

Take an Intra-Individual Approach

It is often a mistake to compare an athlete’s psychological test results with the norms, even though in some cases such a comparison might be useful. Athletes or exercisers might seem to score high or low in anxiety, self-confidence, or motivation in relation to other people, but the more critical point is how they are feeling relative to how they usually feel (an intra-individual approach). Use this psychological information to help them perform better and enjoy the experience more, but relative to their own standards, not the scores of others.

Take the example of assessing an exerciser’s motivation. It isn’t as important to know whether the individual’s motivation to exercise is high or low compared with that of other exercisers as much as how it compares with competing motivations the exerciser has (e.g., being with his family or carrying out his job responsibilities).

Dos and Don'ts in Personality Testing

Do

Don’t

Understand and Assess Specific Personality Components

A clear understanding of the components of personality provides you with some perspective for using and interpreting psychological tests. For example, to measure someone’s personality, you would certainly be interested in her psychological core. You would select specific types of tests to gain an accurate understanding of the various aspects of her personality. To measure more subconscious and deeper aspects of personality, you could use a projective test, for example. Projective tests usually include pictures or written situations, and the test takers are asked to project their feelings and thoughts about these materials. Hence, someone might be shown a photo of an exhausted runner crossing a finish line at the end of a highly contested track race and then be asked to write about what is happening. A high-achieving, confident person might emphasize how the runner made an all-out effort to achieve his goal, whereas a low achiever might project feelings of sorrow for losing the race in a close finish.

Projective tests are interesting, but they are often difficult to score and interpret. Consequently, sport psychologists usually assess personality in sport by looking at typical responses invoked by the actual situation they are interested in. For instance, coaches want to know more than whether an athlete is generally anxious—they also want to know how the athlete deals with competitive anxiety. So a test that measures anxiety in sport would be more useful to a coach or sport psychologist than would a test that measures anxiety in general. Likewise, a test that measures motivation for exercise would be more useful to an exercise leader than a general motivation test would be.

Focusing on Personality Research

The research from the 1960s and 1970s yielded few useful conclusions about the relationship of personality to sport performance. In part these meager results stemmed from methodological, statistical, and interpretive problems, which we discuss later. Researchers were divided into two camps. Morgan (1980) described one group as taking a credulous viewpoint; that is, these researchers believed that personality is closely related to athletic success. The other group, he said, had a skeptical viewpoint, arguing that personality is not related to athletic success.

Neither the credulous nor the skeptical viewpoint appears to have proved correct. Rather, some relationship exists between personality and sport performance, but it is far from perfect. That is, although personality traits and states can help predict sport behavior and success, they are not precise. For example, the fact that some Olympic long-distance runners exhibit introverted personalities does not mean that a long-distance runner needs to be introverted to be successful. Similarly, although many successful middle linebackers in football have aggressive personalities, other successful middle linebackers do not.

We now turn our focus to the research on personality, sport performance, and sport preference. But remember that personality alone doesn’t account for behavior in sport and exercise. Some caution is needed in interpreting the findings of personality research because an attribution or assumption of cause-and-effect relationships between personality and performance was a problem in many of the early studies.

Athletes and Nonathletes

Try to define an athlete. It isn’t easy. Is an athlete someone who plays on a varsity or interscholastic team? Someone who demonstrates a certain level of skill? Who jogs daily to lose weight? Who plays professional sports? Who plays intramural sports? Keep this ambiguity in mind as you read about studies that have compared personality traits of athletes and nonathletes. Such ambiguity in definitions has weakened this research and clouded its interpretation.

One large comparative study of athletes and nonathletes tested almost 2,000 college males using Cattell’s 16 PF, which measures 16 personality factors or traits (Schurr, Ashley, & Joy, 1977). No single personality profile was found that distinguished athletes (defined for the study’s purposes as a member of a university intercollegiate team) from nonathletes. However, when the athletes were categorized by sport, several differences did emerge. For example, compared with nonathletes, athletes who played team sports exhibited less abstract reasoning, more extroversion, more dependency, and less ego strength. Furthermore, compared with nonathletes, athletes who played individual sports displayed higher levels of objectivity, more dependency, less anxiety, and less abstract thinking.

Hence, some personality differences appear to distinguish athletes and nonathletes, but these specific differences cannot yet be considered definitive. Schurr and colleagues (1977) found that team-sport athletes were more dependent, extroverted, and anxious but less imaginative than individual-sport athletes. Of course, it’s possible that certain personality types are drawn to a particular sport, rather than that participation in a sport somehow changes one’s personality. The reasons for these differences remain unclear.

Female Athletes

As more women compete in sport, we need to understand the personality profiles of female athletes. In 1980, Williams found that successful female athletes differed markedly from the “normative” female in terms of personality profile. Compared with female nonathletes, women athletes were more achievement oriented, independent, aggressive, emotionally stable, and assertive. Most of these traits are desirable for sport. Apparently, outstanding athletes have similar personality characteristics, regardless of whether they are male or female.

Positive Mental Health and the Iceberg Profile

After comparing personality traits of more successful with less successful athletes using a measure called the Profile of Mood States (POMS), Morgan developed a mental health model that he reported to be effective in predicting athletic success (Morgan, 1979b, 1980; Morgan, Brown, Raglin, O’Connor, & Ellickson, 1987). Basically, the model suggests that positive mental health as assessed by a certain pattern of POMS scores is directly related to athletic success and high levels of performance.

Morgan’s model predicts that an athlete who scores above the norm on the POMS subscales of neuroticism, depression, fatigue, confusion, and anger and below the norm on vigor will tend to pale in comparison with an athlete who scores below the norm on all of these traits except vigor, instead scoring above the norm on vigor. Successful elite athletes in a variety of sports (e.g., swimmers, wrestlers, oarsmen, and runners) are characterized by what Morgan called the iceberg profile, which reflects positive mental health. The iceberg profile of a successful elite athlete shows vigor above the mean of the population but tension, depression, anger, fatigue, and confusion below the mean of the population (see figure 2.3a). The profile looks like an iceberg in that all negative traits are below the surface (population norms) and the one positive trait (vigor) is above the surface. In contrast, less successful elite athletes have a flat profile, scoring at or below the 50th percentile on nearly all psychological factors (see figure 2.3b). According to Morgan, this reflects negative mental health.

Performance Predictions

Morgan (1979b) psychologically evaluated 16 candidates for the 1974 U.S. heavyweight rowing team using the POMS, correctly predicting 10 of the 16 finalists. Success with this and similar studies led Morgan to conclude that more successful athletes exhibit the iceberg profile and more positive mental health than those who are less successful. You might think that these impressive statistics mean you should use psychological tests for selecting athletes to a team. However, as you will later read, most sport psychologists vehemently oppose using psychological tests for team selection and, in fact, Morgan did not think the test should be used for selection purposes. Personality testing is far from perfect (only 10 of 16 rowers were correctly predicted), and use of testing for selection might mean that athletes will be unfairly and erroneously selected to or cut from a team.

Although Morgan’s mental health (iceberg profile) model is still supported in the literature (Raglin, 2001b), it has received some criticism in recent years (Renger, 1993; Rowley, Landers, Kyllo, & Etnier, 1995; Prapavessis, 2000; Terry, 1995). Renger (1993), for instance, believed that results had been misinterpreted. According to Renger, there was insufficient evidence to conclude that the profile differentiates athletes of varying levels of ability; instead, it only distinguished athletes from nonathletes. Similarly, Rowley and colleagues (1995) conducted a statistical review (called a meta-analysis) of all the iceberg profile research and found that the profile did indeed differentiate successful from less successful athletes but accounted for a very small percentage of their performance variation (less than 1%). Rowley and his coauthors warned that the evidence does not justify using the instrument as a basis of team selection and that users must be careful to protect against social desirability effects (participants “faking good” to impress their coaches). Terry (1995) also warned that the POMS is not a test for “identifying champions,” as Morgan had originally proposed in his iceberg profile model of mental health. At the same time, according to Terry, this does not imply that the test is useless. He indicated that optimal mood profiles are most likely sport dependent; therefore, mood changes in athletes should be compared with their own previous mood levels and not with large-group norms. Drawing on research and his experience in consulting with athletes, Terry recommended that the POMS test be used in the following ways:

Thus, iceberg profile research clearly has implications for professional practice. However, the recent criticisms of this research have shown that it is not possible on the simple basis of giving a personality measure to realistically select teams or accurately predict major variations in athletic performance. Personality data of this type, however, have some useful purposes. Such data can help sport psychologists discover the kinds of psychological traits and states associated with successful athletes, and once these psychological factors are understood, athletes can work with sport psychologists and coaches to develop psychological skills for improving performance. For example, psychological skills training (see chapters 11–16) can help exercisers and athletes cope more effectively with anger and anxiety.

In summary, personality tests are useful tools that help us better understand, monitor, and work with athletes and exercisers. They are not magical instruments that allow us to make sweeping generalizations about individuals’ behaviors and their performances.

Exercise and Personality

Sport psychologists have investigated the relation between exercise and personality. We briefly review the relation between exercise and two personality dispositions: Type A behavior and self-concept.

Type A Behavior

The Type A behavior pattern is characterized by a strong sense of urgency, an excess of competitive drive, and an easily aroused hostility. The antithesis of the Type A behavior pattern is called Type B. Initially, a link was found between Type A behavior and increased incidence of cardiovascular disease. Later, it was suspected that the anger–hostility component of the Type A construct is the most significant disease-related characteristic. Although the causes of Type A behavior have not been conclusively determined, considerable evidence points to the sociocultural environment, such as parental expectations of high standards in performance, as the likely origin (Girdano, Everly, & Dusek, 1990).

Early efforts to modify Type A behavior through exercise interventions have had mixed results. One positive study showed that a 12-week aerobics program not only was associated with reductions in Type A behavior but also helped participants significantly reduce cardiovascular reactivity to mental stress (Blumenthal et al., 1988). Thus, changing Type A behavior patterns through exercise could result in positive health benefits.

Self-Concept

Exercise appears to have a positive relationship also with self-concept (Biddle, 1995; Marsh & Redmayne, 1994; Sonstroem, 1984; Sonstroem, Harlow, & Josephs, 1994). Sonstroem (1984) suggested that these changes in self-concept might be associated with the perception of improved fitness rather than with actual changes in physical fitness. Although studies so far have not proved that changes in physical fitness produce changes in self-concept, exercise programs seem to lead to significant increases in self-esteem, especially with subjects who initially show low self-esteem. For example, Martin, Waldron, McCabe, and Yun (2009) found that girls participating in the Girls on the Run program experienced positive changes in their global self-esteem and in appearance, peer, physical, and running self-concepts.

Parallel to the sport personality research, the exercise and self-concept research has shown that it is best to think of self-concept or self-esteem not only as a general trait (global self-esteem) but also as one that includes numerous content-specific dimensions, such as social self-concept, academic self-concept, and physical self-concept. As you might expect, research shows that exercise participation has the greatest effect on the physical dimension of self-concept (Fox, 1997; Marsh & Sonstroem, 1995; Spence, McGannon, & Poon, 2005). This relationship is discussed further in chapter 17.

Examining Cognitive Strategies and Success

Although some differences are evident among the personality traits and dispositions of athletes and exercisers, researchers have not been satisfied with the utility of the information thus far. For this reason many contemporary investigators have adopted the phenomenological approach to studying personality and turned from studying traditional traits to examining those mental strategies, skills, and behaviors that athletes use for competition and their relationship to performance success (Auweele, Cuyper, Van Mele, & Rzewnicki, 1993; Vealey, 2002).

One of the first studies to take this approach was an investigation by Mahoney and Avener (1977) of gymnasts competing for berths on the U.S. men’s gymnastics team. The authors found that the gymnasts who made the team coped better with anxiety, used more internal imagery, and used more positive self-talk than those who didn’t make the team.

Smith, Schutz, Smoll, and Ptacek (1995) developed and validated a measure of sport-specific psychological skills, the Athletic Coping Skills Inventory-28 (ACSI). The ACSI not only yields an overall score of an athlete’s psychological skills but also gives seven subscale scores, which include the following:

Smith and colleagues examined the relationship between the overall scale and subscale scores and athletic performance in two studies. In the first study (Smith et al., 1995), 762 high school male and female athletes representing a variety of sports completed the ACSI. They were classified as “underachievers” (those who had a coach’s talent rating that exceeded their actual performance ratings), “normal achievers” (those who had ratings equal to their actual performance), and “overachievers” (those who were rated by their coaches as performing above their talent level). The study showed that the overachieving athletes had significantly higher scores than the other groups on several subscales (coachability, concentration, coping with adversity), as well as higher total scale scores. These results show that psychological skills can assist athletes in getting the most out of their physical talent.

The sample in the second study (Smith & Christensen, 1995) was a quite different group of athletes: 104 minor league professional baseball players. Scores on the ACSI were related to such performance measures as batting averages for hitters and earned run averages for pitchers. Interestingly, as with the high school athletes from the first study, expert ratings of physical skills did not relate to ACSI scores. Moreover, psychological skills accounted for a significant portion of performance variations in batting and pitching, and these skills contributed even more than physical ability. (Remember that these were all highly skilled and talented athletes, so this does not mean that physical talent is unimportant.) Finally, higher psychological skill scores were associated with player survival or continued involvement in professional baseball 2 and 3 years later. Thus, performance in elite sport appeared to be clearly related to mental skills.

A third study using the ACSI was conducted with Greek athletes (basketball, polo, and volleyball) at both the elite and non-elite levels (Kioumourtzoglou, Tzetzis, Derri, & Mihalopoulou, 1997). It revealed a number of differences, most notably that the elite athletes all showed superior ability, compared with the non-elite controls, to cope with adversity. The elite athletes were also better at goal setting and mental preparation.

Although Smith and his colleagues (1995) acknowledge that the ACSI is a useful measurement tool for research and educational purposes, they warned that it should not be used for team selection. They argued that if athletes think the ACSI is being used for selection purposes, they are likely to knowingly give answers that will make themselves look good to coaches or to unwittingly give certain responses in hopes that they will become true.

In-Depth Interview Techniques

Researchers have also attempted to investigate the differences between successful and less successful athletes by taking a qualitative approach (a growing methodological trend in the field, as mentioned in chapter 1). In-depth interviews probe the coping strategies that athletes use before and during competition. The interview approach provides coaches, athletes, and sport psychologists with much more in-depth personality profiles of an athlete than do paper and pencil tests. For example, all 20 members of the 1988 U.S. Olympic freestyle and Greco-Roman wrestling teams were interviewed. Compared with nonmedalist wrestlers, Olympic medal winners used more positive self-talk, had a narrower and more immediate focus of attention, were better prepared mentally for unforeseen negative circumstances, and had more extensive mental practice (Gould, Eklund, & Jackson, 1993).

One wrestler described his ability to react automatically to adversity:

Something I’ve always practiced is to never let anything interfere with what I’m trying to accomplish at a particular tournament. So, what I try to do is if something is [maybe going] to bother me … completely empty my mind and concentrate on the event coming up…. My coping strategy is just to completely eliminate it from my mind, and I guess I’m blessed to be able to do that. (Gould, Eklund, & Jackson, 1993)

Medalists seemed able to maintain a relatively stable and positive emotional level because their coping strategies became automatic, whereas nonmedalists experienced more fluctuating emotions as a consequence of not coping well mentally. Take the following example of a nonmedalist Olympic wrestler:

I had a relaxation tape that seemed to give me moments of relief…. It got to the point where what you would try to do was not think about wrestling and get your mind on other things. But inevitably … you would bind up and get tight, [your] pulse would pick-up, and your palms and legs and hands or feet [would be] sweating. You go through that trying to sleep, and I would resort to my relaxation tape. I don’t think I coped very well with it really. (Gould, Eklund, & Jackson, 1993)

Mental Strategies Used by Successful Athletes

Mental Plans

Mental planning is a large part of cognitive strategies. Some additional quotes from other Olympic athletes may help to further explain the benefits and workings of the mental strategies mentioned by the wrestlers just quoted (Orlick & Partington, 1988):

The plan or program was already in my head. For the race I was on automatic, like turning the program on cruise control and letting it run. I was aware of the effort I was putting in and also of my opponent’s position in relation to me, but I always focused on what I had to do next.

Before I start, I focus on relaxing, on breathing calmly. I feel activated but in control since I’d been thinking about what I was going to do in the race all through the warm-up. I used the period just before the start to clear my mind, so when I did actually start the race all my thoughts about what I would be doing in the race could be uncluttered.

I usually try to work with my visualization on what is likely I’m going to use. Different wrestlers have different moves, you know. They always like to throw a right arm spin or something, and I’ll visualize myself blocking that and things like that.

Olympic athletes learn a systematic series of mental strategies to use before and during the competition,

including refocusing plans. Thus, they come prepared mentally not only to perform but also to handle distractions and unforeseen events, before and during the competition (Orlick & Partington, 1988; Gould & Maynard, 2009). These mental plans especially help athletes whose sense of control (a personality trait) is low; the plans allow them to feel more in control, regardless of situational influences. Figure 2.4 provides an example of a detailed refocusing plan for a Canadian Olympic alpine skier.

This skier’s refocusing plan to meet the demands of the situation shows how important it is to study not only an athlete’s personality profile but also an in-depth description of his or her cognitive strategies and plans. In this way, coaches can continually structure practices and training environments to meet the situation and maximize performance and personal growth.

Identifying Your Role in Understanding Personality

Now that you have learned something about the study of personality in sport and exercise settings, how can you use the information to better understand the individuals in your classes and on your teams? Later chapters will explore the practical aspects of changing behaviors and developing psychological skills. In the meantime, use these guidelines to help you better understand the people with whom you work now and to consolidate what you have learned about personality structure.

1. Consider both personality traits and situations. To understand someone’s behavior, consider both the person and the situation. Along with understanding personality, always take into account the particular situation in which you are teaching or coaching.

2. Be an informed consumer. To know how and when to use personality tests, understand the ethics and guidelines for personality testing. This chapter has provided some guidelines, and as a professional it will be your responsibility to understand the dos and don’ts of personality testing.

3. Be a good communicator. Although formal personality testing can disclose a great deal about people, so can sincere and open communication. Asking questions and being a good listener can go a long way toward establishing rapport and finding out about an individual’s personality and preferences. A more detailed discussion of communication is presented in chapter 10.

4. Be a good observer. Another good way to gain valuable information about people’s personalities is to observe their behavior in different situations. If you combine your observation of an individual’s behavior with open communication, you’ll likely get a well-rounded view and understanding of his or her personality.

5. Be knowledgeable about mental strategies. A constellation of mental strategies facilitates the learning and performance of physical skills. Be aware of and implement these strategies appropriately in your programs, selecting them to benefit an individual’s personality.

Nature Versus Nurture and Gravitation Versus Change

Given recent advances in genetic research and testing, the question of whether personality is determined genetically (by nature) or through the environment (by nurture) is highly relevant to sport and physical activity professionals. Although this issue has not been studied in sport and exercise psychology per se, general psychological research shows both that personality has a genetic base (up to 50–60%) and that it is influenced by learning. Both extreme positions regarding nature versus nurture, then, are false. Genetics and the environment determine one’s personality. Moreover, some research suggests that although we may be genetically predisposed to have certain characteristics, whether and how much we manifest these characteristics are influenced by our environment. In sport and exercise psychology, then, we focus primary attention on learning and environmental influences because regardless of the role of genetics in personality, sport and exercise science professionals can influence personality develop-

ment.

A second critical question addressed in personality research focuses on the notion of whether certain individuals gravitate to specific sports because of their personality characteristics (the gravitation hypothesis) or whether one’s personality changes as a result of sport and physical activity participation (the change hypothesis). Although some evidence exists for both notions, neither has been convincingly demonstrated, most likely because both have an element of truth.

Learning Aids

Summary

1. Describe what makes up personality and why it is important.

Personality refers to the characteristics or blend of characteristics that makes individuals unique. It comprises three separate but related levels: a psychological core, the most basic and stable level of personality; typical responses, or the ways each person learns to adjust to the environment; and role-related behaviors, or how a person acts based on what she perceives the situation to be. Role-related behavior is the most changeable aspect of personality. Understanding personality will help you improve your teaching and coaching effectiveness.

2. Discuss major approaches to understanding personality.

Five major routes to studying personality in sport and exercise are the psychodynamic, trait, situation, interactional, and phenomenological approaches. The psychodynamic approach emphasizes the importance of unconscious determinants of behavior and of understanding the person as a whole. It has had little impact in sport psychology. The trait approach assumes that personality is enduring and consistent across situations and that psychological traits predispose individuals to behave in consistent ways, regardless of the situation. In contrast, the situational approach argues that behavior is determined largely by the environment or situation. Neither the trait nor the situational approach has received widespread support in the sport psychology literature. Most researchers take an interactional approach to the study of sport personality, which considers personal and situational factors as equal determinants of behavior. The phenomenological approach focuses on a person’s understanding and subjective interpretation of himself and his environment versus fixed traits. This highly held view is also consistent with the interactional view in that behavior is believed to be determined by personal and situational factors.

3. Identify how personality can be measured.

To measure personality, an interactional approach should assess both psychological traits (an individual’s typical style of behaving) and states (the situation’s effects on behaviors). Although general personality scales provide some useful information about personality states and traits, situation-specific measures (e.g., sport-specific measures) predict behavior more reliably.

4. Assess personality tests and research for practicality and validity.

Although useful, psychological tests alone have not proved to be accurate predictors of athletic success. And when they are used, they must be used ethically. Personality test users must know the principles of testing and measurement error; know their own limitations relative to test administration and interpretation; avoid using tests alone for team selection; always give athletes test explanations and feedback; assure athletes of confidentiality; take an intra-individual approach to testing; and understand and assess specific personality components.

5. Understand the relationship between personality and behavior in sport and exercise.

Exercise has been found to enhance self-concept, especially the physical component of one’s self. Type A behavior has been shown to be an important personality factor influencing wellness. Although some personality differences have been found through comparison of athletes with nonathletes and comparison of athletes from different sports, the most interesting and consistent findings come from comparisons of less successful athletes with more successful athletes exhibiting more positive mental health. These results, however, have limited application.

6. Describe how cognitive strategies relate to athletic success.

In recent years researchers have turned their attention away from measuring traditional traits and toward examining cognitive or mental strategies, skills, and behaviors that athletes use. Successful athletes, compared with their less successful counterparts, possess a variety of psychological skills. These include arousal regulation and management, high self-confidence, better concentration and focus, feelings of being in control and not forcing things, positive imagery and thoughts, commitment and determination, goal setting, well-developed mental plans, and well-developed coping strategies.

7. Apply what you know of personality in sport and exercise settings to better understand people’s personalities.

As a professional in sport and exercise, you need to gather information about the personalities of people with whom you work. Specifically, consider both personality traits and situations, be an informed consumer, communicate with athletes, observe your subjects, and be knowledgeable about mental strategies.

Key Terms

psychological core

typical responses

role-related behavior

psychodynamic approach

trait approach

situation approach

interactional approach

phenomenological approach

situation-specific measures

intra-individual approach

projective tests

mental health model

iceberg profile

meta-analysis

qualitative approach

Review Questions

1. Discuss the three levels of personality, including the stability of the different levels.

2. What is the psychodynamic approach to personality and why is it important?

3. Compare and contrast the situation, trait, interactional, and phenomenological approaches to personality. Which approach is most common among sport psychologists today? Why?

4. Discuss three problems in early personality research in sport and exercise settings.

5. Compare and contrast state and trait measures of personality. Why are both needed for a better understanding of personality in sport?

6. Why are sport-specific personality inventories more desirable than general psychological inventories for measuring personality in sport and exercise? Name examples of both sport-specific and general personality measures.

7. Discuss four important guidelines for administering psychological tests and providing feedback from the results of these tests.

8. Discuss the research comparing the personalities of athletes and nonathletes. Do athletes have a unique personality profile?

9. Do male and female athletes have different personality profiles? Are the differences between male and female athletes as great as those between athletes and nonathletes? Do individual- and team-sport athletes have different personality profiles?

10. Discuss Morgan’s mental health model and the iceberg profile as they relate to predicting athletic success. Can athletic success be predicted from psychological tests? Explain.

11. What personality factors are related to exercise behavior?

12. Compare and contrast the cognitive strategies of successful athletes with those of less successful ones.

Critical Thinking Questions

1. Should psychological tests be used for team selection? Explain your answer.

2. What is your role in understanding personality? When might you consider using personality tests? Discuss other ways to assess participants’ personalities.