Energy Channels

To carry out its functions, the energy within and around your body must be able to travel where it is needed, and one way people have perceived and measured these energy flows is as a network of lines or channels, like energetic rivers and streams. These lines go by different names, such as the meridians in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), nadis in Hindu spiritual science, and sen in traditional Thai medicine. In this chapter, we will be focusing on the meridians and nadis, but know that there are other valid approaches to perceiving how energy travels throughout the human system.

In physics, in order for energy to flow there must be a difference between one point or area and another. For example, heat will flow from warm areas to cooler ones, and electrically charged particles will flow from areas of high potential to areas of low potential, creating an electric current in the process. In addition, particles typically cannot move through all materials willy nilly; there are conditions that limit the path and quality of this flow. Again using electricity as an example, the material in question must be a good conductor in order for an electric current to be established. You won’t have the same effect using a piece of rubber as you would a copper wire. So, too, in the body, there are distinct pathways through which different types of energy are conducted more easily, and these are the meridians (or nadis, sen, etc.).

If you look at diagrams for meridians and other energy lines in books, it’s easy to walk away with the impression that everyone’s meridians are exactly the same, and indeed, it does appear that there is a great deal of consistency from person to person. However, just like with our flesh and bone anatomy, differences can and do exist, and beyond congenital variations, we can also alter our physical and energetic makeup based on usage patterns. When working with the meridians, energy medicine looks at how energy is flowing through these channels, and practitioners use abnormalities in this flow to pinpoint underlying issues. Reestablishing healthy flow, which involves balancing over- and under-energized areas, can support healing on many levels.

Meridians

Meridian therapy has a long history in Chinese culture. The Chinese word for meridian is ching-lo. It is sometimes written jing-luo, and it can be translated as “to pass through” (ching) and “to connect” (lo).1 The meridians allow for the passage of chi, also spelled qi, or vital life force energy, which is synonymous with ki in Japanese healing. Along the meridians are precisely mapped points or entryways to the meridians. These are commonly called acupuncture or acupressure points and are the site for needling or manual pressure during a meridian-based treatment.

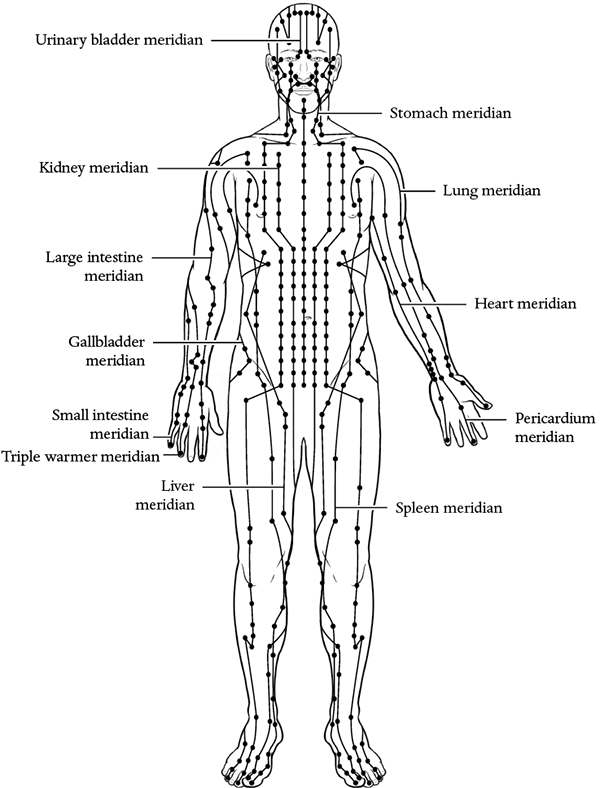

There are twelve major meridians that create a network of energy channels throughout the body, supplying and removing chi to and from the various organ systems. The meridians are as follows:

• Lung (yin, metal)

• Large intestine (yang, metal)

• Stomach (yang, earth)

• Spleen (yin, earth)

• Heart (yin, fire)

• Small intestine (yang, fire)

• Urinary bladder (yang, water)

• Kidney (yin, water)

• Pericardium (yin, fire)

• Triple warmer (yang, fire)

• Gallbladder (yang, wood)

• Liver (yin, wood)

Figure 3: The 12 meridians, anterior view

Each meridian is associated with the energetic quality of yin or yang (as well as one of the five elements, which we’ll discuss below). Yin-yang theory states that there are two basic forces: the yang force is associated with qualities like excitatory, dynamic, and stimulating and is traditionally described as male, while yin is inhibiting, static, calming, and traditionally described as female. These dual energies are like two sides of the same coin. Yin becomes yang and yang becomes yin in a dynamic flow, and the union of the two creates a supreme energy that gave rise to the universe and continues to flow through all things. This is strikingly similar to our discussion earlier in the chapter, in which we saw that an energy current is generated by a difference in state between one point or area and another. It’s possible that the polarity of yin and yang establishes the same sort of energetic differential on a subtle level, giving rise to a current or flow of energy throughout the body via the meridians. Balance between these two forces does not imply a constant equilibrium but rather dynamic checks and balances between doing and being, stimulation and inhibition, and so on. Sometimes life calls for more yin energy lest we become burnt out and depleted, while other times we need a little more get-up-and-go to prevent us from spending all our time binging Netflix.

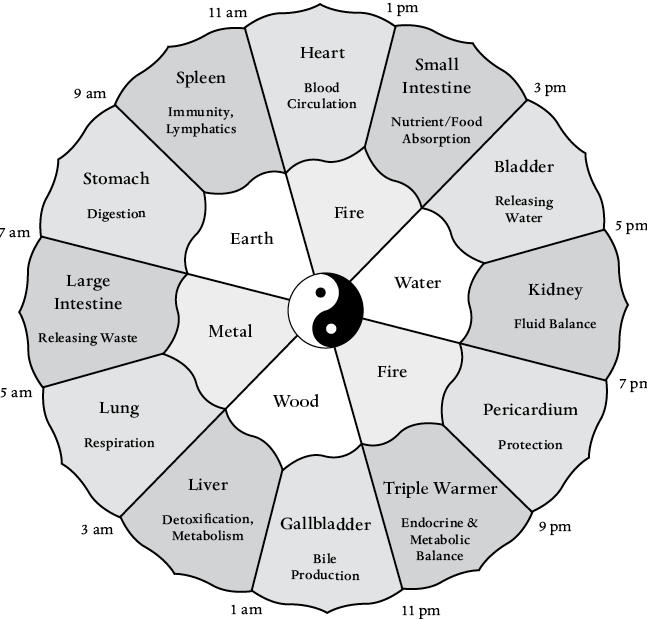

In addition to the exchange between yin and yang, there is also a dynamic flow between the elements of earth, metal, fire, water, and wood, each of which corresponds to a season: late summer, autumn, winter, spring, and summer, respectively. Each season and element give way to the next in an unceasing cycle, and the elements are seen to interact either by generating and increasing one another or by destroying and inhibiting. For example, wood increases or feeds fire, while water quenches fire. These relationships can be used to reintroduce balance: inhibiting elements can be used to decrease an overabundance of another element, while generative elements can increase the potency of weaker elements within the system. There is a complex mapping of symptoms and qualities associated with each element that further enables practitioners to diagnose and treat imbalances, such as anger and irritability suggesting an excess of wood, or cold feet indicating a water issue.

The elements are also paired with different atmospheric states, and different organ systems prefer a particular state (similar to, in astrology, a planet being in an exalted, or more favorable or powerful, state when it enters a particular sign). These atmospheric states vary somewhat by source, but they are generally listed as wind, cold, heat, wetness, and dryness, with heat sometimes being parsed into heat and summer heat.2 The organ associations are as follows:

Wind: Liver and gallbladder

Cold: Kidney and urinary bladder

Heat: Heart and small intestine

Wetness: Spleen and stomach

Dryness: Lung and large intestine

As chi courses throughout the body’s meridians, it does so in a regular, twenty-four-hour pattern, and this, too, can aid in diagnosis of imbalances. While I studied the five-phase theory of TCM in massage school, this was one of the topics that really hit home. I was astounded to see that the hour at which I had been routinely and inexplicably waking up every night corresponded to the organ system (and corresponding emotions) with which I was experiencing health issues!

Lungs: 3 am to 5 am

Large Intestine: 5 am to 7 am

Stomach: 7 am to 9 am

Spleen: 9 am to 11 am

Heart: 11 am to 1 pm

Small Intestine: 1 pm to 3 pm

Bladder: 3 pm to 5 pm

Kidneys: 5 pm to 7 pm

Pericardium: 7 pm to 9 pm

Triple Warmer: 9 pm to 11 pm

Gallbladder: 11 pm to 1 am

Liver: 1 am to 3 am

In addition to the twelve major meridians, there are the eight extraordinary channels or vessels:

• The Du

• The Ren

• The Dai

• The Chong

• The Yin Chiao

• The Yang Chiao

• The Yin Wei

• The Wang Wei

In contrast to the twelve major meridians, the vessels do not correspond to specific organ systems and are instead responsible for connecting the major meridians to the organs and other parts of the body, helping supply, store, and drain chi as needed. Two of these vessels, the Governor or Governing Vessel, which runs up the back of the body, and the Conception Vessel, which runs up the front of the body, are considered by some practitioners to be part of the main meridian system, giving a total of fourteen meridians.

Interesting research has been conducted on the meridians and acupuncture points in an attempt to see whether they can be mapped using scientific tools and to reveal how acupuncture and acupressure treatments facilitate healing. In a study by Darras, Albarède, and de Vernejoul, radioactive tracers were injected into the body at acupuncture points, and a device known as a scintillation camera, which detects and records radiation emissions, was used to map the migration patterns. These pathways were shown to correspond with the meridians.3

Another study demonstrated a higher concentration of cell gap junctions, which are connections between cells that allow for the passage of various molecules, ions, and electric charge, along the meridians, suggesting higher levels of communication via these pathways. Other researchers have found a close relationship between the locations of peripheral nerves and meridians, and yet another study has demonstrated that the electric potential measured at acupoints was significantly different from surrounding areas, with lower electrical charge in ill patients.4 These data suggest that there are veritable structures related to the meridians, but there is still much to be learned, with some facets perhaps forever remaining beyond the bounds of science to reveal.

Nadis

The word nadi can be translated as “stream,” and like the meridians, they are a network of channels for subtle energies. The first written record of the nadis comes from the Upanishads written in the seventh to eighth centuries BCE, which mentioned 72,000 nadis. Other sources vary from 1,000 to 350,000 nadis. According to tantric yoga, there are two classifications of nadis: subtle (which is further subdivided into manas, mind or mental energy, and chitta, feeling energy) and gross. The subtle nadis are invisible channels for energy, while the gross channels are visible pathways, such as nerves and lymphatic vessels, but both types of channels can transport prana, or life force.

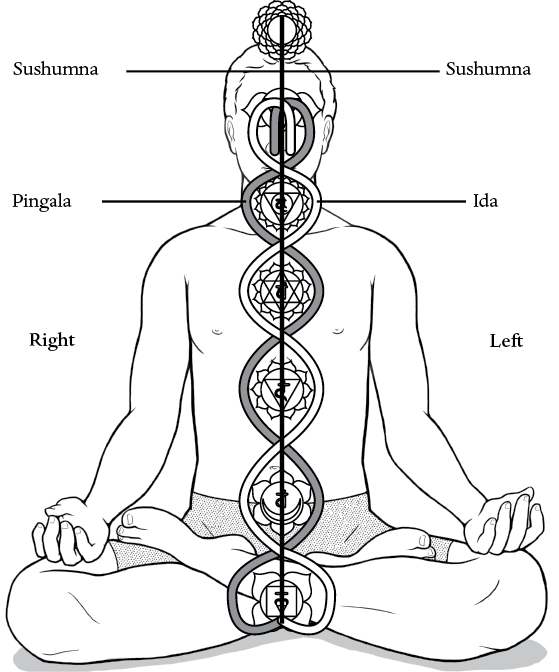

There are three primary nadis, which are integral to kundalini practice, and they are the sushumna, or central channel, the ida, and the pingala. The sushumna travels up the spinal column, along which the primary chakras are arranged. The chakras are energetic centers tasked with receiving and processing energy, which is then transmitted to the rest of the body and energy field via the nadis. The sushumna begins at the base chakra, muladhara, and passes through the crown chakra, or sahasrara, where it splits into two streams: one that passes through the brow chakra (ajna) before reaching the seat of consciousness (Brahma Randhra) between the left and right brain hemispheres, and one that passes behind the skull before entering the seat of consciousness. The sushumna is composed of different nadis, layered like wrappings around an electrical wire. The outermost layer is the sushumna, considered to exist outside of time, and it is wrapped around the vajrini, associated with the sun. The vajrini, in turn, is wrapped around the innermost layer, the chitrini, which is associated with the moon. The trilayered sushumna is responsible for delivering prana to the chakras and other subtle energy structures (in cooperation with the entire network of nadis), and it partners with the ida and pingala to activate the rising of kundalini (more on that follows).

The ida nadi is seen as primarily feminine and associated with the moon, and it is said to be dominant from the new to the full moon. It has calming, peaceful, magnetic, and nurturing qualities and constitutes the left channel of the nadi system. As with TCM’s yin-yang theory, the ida is partnered with the pingala on the right, which is associated with masculine energy and the sun, and the qualities of vitality, power, mental alertness, and taking action. It is dominant from the full to the new moon. The ida and pingala are often depicted as coiling around the central channel of the sushumna, mirroring the image of the caduceus, the medical symbol of the staff entwined by two snakes.

Working with the sushumna, ida, and pingala, kundalini practitioners seek to awaken a type of energy known as kundalini energy (kundalini translates to “she who is coiled” 5 ), which rests in a dormant state at the base of the spine, often depicted as a coiled serpent. Using the breath and trained will, this energy can be guided upward, through the ida and pingala channels, flowing through and stimulating the chakras as it rises, reaching the brow (ajna) chakra, where the energy streams join the sushumna and crown chakra, initiating what has been described by practitioners as a state of enlightenment or liberation (moksha), which can include mental and psychic clarity, physical healing and renewed vitality, and the awakening of siddhis, which are considered to be supernatural or otherwise elevated powers. It is said that without proper training, this awakening can be dangerous, triggering mental or psychic instability, while others claim that rather than causing harm, the experience will simply be short-lived and difficult to translate into lasting change without sufficient preparation.

In addition to the three primary nadis, there are additional pathways that aid in the transmission of energy throughout the body. As with other systems, health is seen to arise from a healthy flow of energy throughout these channels, and various tools have been developed to aid in this balancing process, such as the physical postures of yoga (asanas) and breath control (pranayama).

While systems for mapping energetic channels throughout the body vary to some degree, what is agreed upon is the need for energy to flow without obstructions, in the right amounts, and to the proper locations to support health. In the next chapter, we’ll explore one more feature of our energetic anatomy: energy bodies, also known as chakras, that lie along the various channels and are responsible for processing energy both from the external environment and from within.

1. Dale, The Subtle Body, 161.

2. Subhuti Dharmananda, “The Six Qi and Six Yi,” November 2010, http://www.itmonline.org/articles/six_qi_six_yin/six_qi.htm.

3. J. C. Darras, P. Albarède, and P. de Vernejoul, “Nuclear Medicine Investigation of Transmission of Acupuncture Information,” Acupuncture in Medicine 11, no. 1 (1993), 22–28, doi:10.1136/aim.11.1.22.

4. Andrew C. Ahn et al., “Electrical Properties of Acupuncture Points and Meridians: A Systematic Review,” Bioelectromagnetics 29, no. 4 (May 2008): 245–56, doi:10.1002/bem.20403.

5. James Mallinson and Mark Singleton, trans. and eds., Roots of Yoga (London: Penguin Books, 2017), 178.