goats

One of the most versatile of farm animals, the goat can also be the most challenging to raise.

Goats of any age will test every door, attempt to jump over every obstacle, and taste every object in their world.

A goat, it has been said, is “like a three-year-old in a goat suit.”

If you’ve ever thought you might like to try your hand at running a day care for preschoolers, you’ll love looking after a few goats. They are both sweetness and shenanigans, loving and annoying, obedient and troublemakers—all within minutes of each other. They can double you over with laughter as easily as they make you cry out in absolute frustration.

With all the raw emotions that a goat or two can bring out in their keepers, they still count as the most versatile of all farm animals. With the right conditions one goat could supply your family with milk, low-fat meat, and an income throughout the year.

Milk from a backyard dairy goat can be used for household consumption and to make luxurious soaps. Although laws that allow the sale of milk are stringent, you could easily sell the soap as a high-end beauty product through multiple venues.

When compared to cow milk, goat milk is higher in phosphorous, riboflavin, niacin, calcium, and vitamins A and B1, and is lower in cholesterol. Right off the udder, goat milk is loaded with antibodies and has a much lower bacterial count than cow milk. Based on these and other benefits, goat milk is often recommended by doctors to safely treat physical conditions including eczema, vomiting (dyspepsia), and insomnia in infants, pregnant women, and children.

Goat milk is decidedly richer in flavor than cow milk if you are used to 1 or 2 percent milk from the grocer’s shelves. As you’ll see in the breed section (following) some goats produce milk that is up to 6 percent butterfat.

Although the milk may be high in fat, the meat from a goat is not. Found most often for sale within Spanish, Greek, and Jewish communities, chevon is growing in popularity across the United States and Canada. Chevon is the meat from a young, but mature, goat. Cabrito or chevrette is the term for meat from a milk-fed kid. The less tender meat from an older goat is called chivo or mutton (a term commonly used for older sheep meat).

Goats will give you much more than milk and meat though. You might be able to sell the hair from your goats or use them to control overgrowth on your land. A goat or two can make short work of returning a neglected homestead to its former beauty.

Measured by all these benefits, goats are a surprisingly inexpensive purchase and are also cheap to keep.

A final blessing of keeping goats is the fiber many of the breeds produce, known as cashmere. Cashmere is still the lightest weight, warmest, and most completely non-irritating fiber known to man. This down-like hair grows under the primary hairs of goats raised in cold climates where extra warmth is required. In most cases a cashmere-producing goat will only create a quarter to a third of a pound per year.

Goats Are Smelly. Does smell like pasture, fresh air, and hay. It is the buck that carries the offensive odor that gives goats a bad name. Bucks have two major scent glands located slightly behind and between the horn area. The odor is strongest during breeding season.

Goats Are Mean. As a rule, goats are not mean. When raised with understanding and care they develop an eagerness to please their owners. Goats can be trained to come to their name, pull a cart or field tiller, and be led peacefully by a rope. If you’ve met a mean goat, you’ve either been in the presence of an uncaring owner or somehow the goat felt threatened and displayed aggression in an attempt to protect itself.

A Goat Will Eat Everything in Sight. Goats are inquisitive animals that explore their world orally. Few goats will swallow objects that don’t taste good. Proper fencing is a top priority when raising goats to ensure they don’t “explore” your prized roses or climb onto your pickup truck to see what’s inside.

Choosing the Right Breed for Your Needs

Pure goat breeds are separated into three main groups for farm use—milk, meat, and fiber. A milk or fiber goat can be raised for meat. A meat or milk goat can produce salable fiber. Fiber and meat goats can be milked. Even though all goats are triple-blessed, not one breed is versatile or exceptional enough to be classified as such.

Around the world more than two hundred breeds of goat exist. Eighty of these are registered for agricultural use. The breed you choose will depend on your family’s needs, your ultimate goal, and regional availability.

Approximately 60 percent of goats currently in North America are mixed breeds (termed “grades” or “scrubs”). These animals are unregistered but they still have use and purpose to a small farm. A grade goat might be a risky proposition to raise for milk, but they are perfectly acceptable animals for meat.

Meat, Milk, and Fiber Yields for Goats

Yields to be expected from registered classes are:

• Dairy—Average doe supplies nine hundred quarts per year.

• Meat—The average buck kid provides twenty-five to forty pounds of meat. Boer goats produce nearly twice as much.

• Fiber—Adult Angoras supply ten to fifteen pounds of mohair per year. Adult cashmere-producing goats might supply a third of a pound per year.

• All—Supply approximately one pound of garden-enhancing manure per day.

Dairy Goat Breeds

Of the six most common dairy goats, the Swiss breeds (Alpine, Oberhasli, Saanen, and Toggenburg) are the hardiest for colder climates. The remaining two (LaMancha and Nubian) are genetically equipped to handle extremely warm and dry climates but may be kept in the North with proper care and consideration.

Nubian—Easily recognized by long droopy ears and wide nostrils. Nubians are the most energetic class and produce milk high in butterfat.

LaMancha—These goats originated in the United States and have very small ears, if ears are at all noticeable. LaManchas are the calmest breed and also produce milk high in butterfat.

Saanen—The largest of the milk goats. Saanens are usually white, with a narrow face and nose. Saanens are one of the top two milk producers. Note: A colored Saanen is called a Sable. Although a Sable is the product of two Saanens with a present recessive gene, Sables are slowly becoming recognized as a separate breed in North America.

The Saanen is one of the top producing milk breeds.

Alpines—(French, Swiss, British, and Rock) Alpines come in a variety of colors, the most common of which is the French White Neck Alpine. These goats match the Saanens in milk production.

Toggenburg—Toggenburgs are the oldest registered breed. Usually brown (from creamy to dark brown) and showing white stripes or patches above each cheekbone, on the ears, inside the legs, and/or on the rump.

Oberhasli—You can easily see the genetic cousins of goats (deer) in the Oberhasli. These goats are small, like the Toggenburgs, and are easily distinguished by their thin faces and coats of russet brown, often with black markings.

The Boer breed has been quickly gaining in popularity across the United States and Canada.

Although any breed of goat (including the scrub) can be used for meat, this classification is specific to the few breeds that grow the quickest and add more lean muscle fiber than other classifications of goats.

The Spanish and Myotonic goats have been raised for centuries by North American farmers to provide a reliable meat source for their families. Both breeds grow to decent proportions and are well-muscled animals. Spanish bucks grow to an average of 175 pounds and their partners to 100 pounds. Myotonic bucks can weigh up to 140 pounds and the does approximately 75 pounds at maturity.

The Myotonic goat is also known as the Tennessee fainting goat. This goat was introduced into America by a Nova Scotian (Canadian) breeder. The animal’s success as well as its shortcoming is the result of a genetic disorder causing it to react to fright with muscle spasms. The goat, when startled, will stiffen his legs, lose his balance in the process, and fall to the ground. The repeated stiffening gives the goat muscular thighs—enough so to be classified as a meat goat. Unfortunately this condition also renders the animal helpless in the pasture until the myotonia dissipates.

In the last century a new breed has entered North American soils. This breed, the Boer, hails from South Africa, where it was developed for size, speed of growth, meat quality, and uniformity of coat color. The Boer is statuesque in comparison to the native North American goats. A mature buck can tip the scales at more than 300 pounds, a doe at 220 pounds.

With a history and development similar to the Boer’s, another new breed of meat goat is being introduced to the world from New Zealand. The Kiko goat is the product of a government-funded initiative that began in the 1970s to crossbreed wild with domestic goats to produce a faster-growing meat breed. Within just a few generations and minor variations during development, the Kiko was established as a breed. Kikos are now proven to have the highest occurrence of kidding twins, a fast and reliable growth rate, and a hardiness to disease and harsh weather.

Goats produce two distinct fibers—mohair and cashmere. While mohair is only produced by the Angora goat, cashmere can be found on more than sixty of the world’s goat breeds. (In North America we most often find cashmere on northern-raised Spanish and Myotonic breeds.)

Finding a top-producing cashmere goat is difficult in North America, not to mention an expensive acquisition for the small herder. Goats in the top of their class for producing cashmere often net a few thousand dollars upon sale and yet may only produce a quarter to a third of a pound of fiber per year.

Angoras, on the other hand, are a pure and registered breed. These silky-haired goats generate eight to twelve pounds of mohair annually. A wether (castrated male) produces slightly more than a doe.

The Angora is certainly in a class of its own, but the care is similar to that of other goat breeds. If you are only planning on keeping a few and hope to sell the fiber twice a year, find a local breeder or Angora goat group to collaborate with. Not only will they share invaluable breeding, feeding, and coat care tips, they will also assist you in finding a buyer for your yield.

Miniature Breeds

Miniatures are currently popular on farms with limited space for both meat and milk production. The miniatures also make great pets and are easy enough for most children to handle. These goats are one-third to two-thirds the size of an average milk goat and therefore require much less space and food.

Nigerian Dwarf—At seventeen to twenty inches tall, this miniature dairy goat is capable of producing one quart of milk per day (ample for a small family) and requires a third of the space and feed that a full-size milk goat requires. Mature does average thirty to fifty pounds. Bucks and wethers average thirty-five to sixty pounds.

African Pygmy—These well-natured dual-purpose goats are often displayed at petting zoos. They stand eighteen to twenty-four inches tall, but their stocky build weighs them in at between thirty-five and seventy pounds. Their milk is higher in butterfat than any other goat (approximately 6 percent), and their muscular nature makes them a viable meat breed as well.

Although there are only two recognized miniatures, a few crossbreeds are gaining in popularity. The Pygora (a cross between an Angora and a Pygmy) produces a lesser-grade mohair but will also produce the fine down a Pygmy provides, and will finish a little larger for freezer meat.

Another dual-purpose crossbreed is the Kinder (a cross between a Pygmy and a Nubian). This breed has been gaining in popularity since first introduction in 1986. Kinders have been recorded to produce three to six kids annually, and some have been rated as top performing milkers (see the description of top performing milkers on page 77).

Designing Your Small Farm Strategy

As goats are herd animals, it is best to have more than one. They are not meant to be the only one of their kind on a farm, but they will bond and make friends with any other four-legged farm animal with which you house them. At any rate, if one is a charming addition to your farm, two will be twice the fun.

There are many options to consider when designing a small farm strategy to suit your needs. A few scenarios follow.

• Raise dairy goats with the added benefit of meat once per year: Purchase two bred or breeding dairy does. Breed them every year, four to six months apart from each other, to keep the milk flowing. Increase your herd by keeping the doelings or fill your freezer by growing the bucklings on supplemented pasture for four to six months. If you don’t intend to increase your herd and your original does are of good stock, you can sell the young dairy does to other farms.

• Raise goats for meat and a little milk: Purchase two bred does of any breed (or have them bred) and continue to breed for the next few years. Keep or grow doelings and grow the bucklings for a few months.

• Raise goats for meat only: Purchase two wethers. Boer or Boer-cross wethers will yield the most meat in the shortest possible time.

• Raise goats for fiber with no interest in breeding or a milk supply: Purchase and keep wethers long-term. Wethers yield a higher fiber count, are cheaper to purchase, and grow larger than a doe.

• Raise Angora goats for income or for meat: Purchase two bred does, raise the offspring on supplemented pasture for meat, have some milk for personal use, and during shearing season make a little extra income.

Raising Kids for Meat

One of the most popular small farm strategies involves breeding milk does to keep them in production and raising the kids for just a few months to supply meat for the freezer. Others purchase weaned kids to raise for meat and are done with chores by winter solstice.

Whichever strategy you employ, your goal is to raise the largest possible kid, in the shortest period of time, at the lowest possible cost. The least expensive goat meat to raise is the six- to eight-week-old milk-fed kid weighing about thirty-five pounds. Since this kid will only net fifteen to twenty pounds of freezer meat, grow him on for a larger yield. By twelve weeks of age the average goat will weigh fifty pounds and will have only cost you a few dollars in grain. Put that same kid on pasture (with normal supplemental feeding), and by the time he’s reached seven to eight months he should weigh in at eighty pounds.

Just by adding an extra five months of pasture grazing and a few pounds of grain, you’ve increased your freezer meat profit by 400 percent. The exception to this rule of increase is the Boer goat. Boers are larger at birth and grow faster and larger than any other goat in the same amount of time.

The Goat Barn, Yard, and Pasture

Whenever you need to set up an area for goats—inside or out—it is beneficial to remember the adage of a goat, “like a three-year-old in a goat suit.”

If a barrier can be jumped over, an electrical wire reached, glass windows pushed upon, grain accessed, or nails stepped on, it will be. Any object within reach will be challenged, broken, eaten, chewed, ripped, pushed, or punctured by a goat. If you wouldn’t leave your three-year-old nephew alone for twenty minutes in the shelter or hope to hold him with the fence you just built, it probably isn’t adequate for a goat either.

Goats won’t take up much room on your farm. Their housing requirements are nearly as casual as those required for chickens. In fact, a large shed will do just fine for a few goats. With just a little ingenuity and room in your budget you can have the ideal setup for keeping goats.

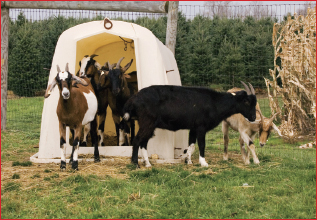

There are two primary methods for housing and containing goats. The first is to pasture them and provide a poor-weather and bedding shelter. The other method, “loafing and confinement,” is to keep goats in a shed or small barn with a fenced yard for exercise.

The loafing-and-confinement system of raising goats is used mainly for dairy and fiber goats or by farmers who don’t have ample pasture. Sufficient room is provided inside and out but keeps high-energy activity to a minimum. Less energy expended allows for productive use of feed.

An average goat only requires twenty square feet indoors, plus two hundred square feet outdoors. Meat goats require more: thirty square feet inside, three hundred outside. Miniatures require a third less than the others.

The Goat Barn

An existing shed conversion may be perfect for housing goats and could save you building a new structure. Knowing the number of goats you will house at the height of the season (your does plus offspring that you keep for five to six months) will determine if an existing building is adequate. A communal stall takes 35 to 50 percent of your floor space and leaves adequate room for a milking station, feed storage, and one or more smaller stalls. The small stall will be used for isolation of a sick goat, quarantining a new goat, kidding, or weaning.

Shed Conversion Example

Two dairy does given forty square feet (twenty square feet each) for a communal stall, plus a smaller stall for kidding (twenty square feet), a section for milking and grain storage (thirty-five square feet), plus twenty square feet extra for two kids annually.

At less than 120 square feet required, a little planning can convert a 10-foot by 12-foot shed into an adequate loafing barn. Tight, but adequate.

Design your floor layout to accommodate the feeding and watering of goats without entering their communal stall. The easiest way to do so is to build a half wall between their space and yours. Your side contains the manger, water bucket, and soda/salt feeder. Their side contains slatted or keyholed head access to all three.

A converted ten-foot by twelve-foot shed showing a milking stand or bench, keyhole manger access, exterior water buckets, and good distribution of space: Sixty-square-foot communal stall, twenty-square-foot kidding stall, and thirty-five square feet of work and storage area. Add an access door to the back wall that opens to their yard and you’re all set to bring a few goats home!

A slatted or keyholed access manger may be the most economical investment of your time in a shed conversion. Goats are not only notoriously picky about the hay they eat, they are also the most wasteful. If they can climb into a manger to eat they will do so, soiling their feed in the process.

At an open manger they are known for taking a mouthful of food, turning to see who might be behind them, and dropping half of their mouthful on the floor in the process. A slatted or keyholed access manger ensures that they can neither swing their heads around nor climb into the manger to eat.

The standard top width of a keyhole is eight to nine inches with a keyhole-shaped taper to the bottom at four to five inches wide. The full height of the keyhole is sixteen inches. Goats will crane their necks to put their heads in at the top and then lower their heads to a comfortable fit within the slot.

If the top of your wall is higher than most of your goats can reach through slats or keyholes, you could build a variable-height step on their side of the wall. Later, kids feeding at the manger will use the higher steps. Keyhole entries won’t work for horned goats.

Temperature

Goats will huddle together and keep each other warm (enduring temperatures to freezing) as long as their goat house is free of drafts and leaks and the bedding is ample and dry. Take extra care for extremely cold days and nights, if kidding is imminent, or if you’ve had early-season births. Extra bedding, a supervised or safe heating unit, and/or a little extra hay for adult goats will help keep the cold out of your herd.

During the summer months you’ll find goats equally resilient, but do not lock them in during the hottest summer nights without a breeze blowing through and plenty of cool water.

Floors and Bedding

The flooring in a goat barn need be nothing more than dirt covered with a thick layer of bedding material. Straw and waste hay are easy to use and inexpensive, but wood shavings are easier for cleaning and more beneficial as a future compost.

Keeping a goat’s bedding clean is of the utmost importance. You won’t have to spend hours cleaning out their pen every morning, though. All that is required is to lay some fresh bedding over the existing every few days.

When you’re cleaning out the stall, be sure to compost the rich organic waste material for at least six months, then add it to your gardens. Compost longer if you’ve been using waste hay as bedding material.

Lighting

As the days grow short over the winter months, you’ll find yourself doing chores in the dark more than once. If you keep dairy goats the addition of lighting performs double duty. Natural and artificial lighting for eighteen to twenty hours per day will maintain milk production through the fall and winter months plus increase the success rates of early spring breeding.

Grain or Goat Ration Storage

Store grain away from all moisture, out of the sun, off the ground, and certainly out of a goat’s reach. Should a goat obtain access to the grain barrel it will eat until the grain is gone—gluttony that could result in death through bloat. A galvanized trash can with a snap-on lid placed well out of reach keeps goats and vermin out of the grain.

The goat yard should be dry at all times to prevent bacterial infections in hooves. If you don’t have a dry area available for goats, a poured concrete pad suffices during the rainy season. It will also keep their hooves neat and trim. Plan for at least part of the yard to be on the south side of the building.

Goats are happiest when they have something to climb on. An outcropping of rocks is ideal, but any sturdy structure will satisfy their instinctual nature to climb. Keep climbing objects well away from the fence or they’ll use them as steps to freedom.

Good fencing will keep your goats safe from harm and your personal property safe from goats.

“A fence that can’t hold water won’t hold a goat” is an age-old axiom. Above all other considerations, the fence deserves the most attention. Goats will go over, under, or through a fence before you’ve taken three steps away from their yard if it hasn’t been built correctly.

• Four-feet-high minimum. Five feet high for the highly active and nimble Nubians and miniature breeds.

• Page wire fencing with twelve-inch openings is acceptable if you will never need to contain kids; otherwise invest in a six-inch page wire. Chain link or stock panels with small openings are equally acceptable.

• Use eight-foot posts, eight to ten feet apart, buried at least thirty inches into the ground. Posts can be steel or wood.

• All corner post supports of a goat yard fence go on the outside. Goats will climb or shimmy up a fence support no matter how slim.

• If building an electric fence only, run the wire, from the bottom up, at five, ten, sixteen, twenty-three, and thirty-one inches, and a final strand at forty inches for all breeds. Electric fencing is not a viable option if power in your area is prone to blackouts, although you can also consider solar-powered electric fence chargers. They are common, effective, and not too expensive. Remove all weeds that touch the wire.

The Gate

Your goats will watch you enter and leave the yard. In doing so they will learn how to operate the lock. As soon as they’ve mastered the latch or handle they’ll be wandering through your flower garden, investigating activity on the road, taking their lunch in the grain fields, or bleating at your front door.

A goat can flip a hook out of the eye it rests in and has the determination to mouth and hoof at a lever latch all day until it opens. Determined goats have even been known to slide a large bolt to the open position.

• Place all slide bolts, latches, or locks on the outside of the gate where the goat can’t reach them.

• Install your gate to swing into the goat yard so that even if one of your escape artists managed to unlatch the gate, she might not know she did so.

The Pasture

The practice of pasturing goats is a personal decision that may be based on breed of goats, farm economics, available pasture, or even your need to have brush cleared on acreage.

As feed can be 70 percent of the cost of keeping any goat, even partially pasturing meat breeds is frugal and wise. Milking does set to managed pasture will create more milk, but it will be lower in butterfat content.

If you will be pasturing your dairy goats, take heed that consumed pungent plants could alter the flavor of milk. Ensure as well that the does aren’t in forest or overgrowth. A milk goat’s udder could easily be scratched or damaged while foraging in such conditions.

Keeping goats on pasture dramatically reduces feed costs.

Allow at least one acre for every ten goats and employ rotational pasturing by moving their pasture as soon as each area looks sparse. Rotating ensures that each pasture remains viable and decreases the potential for parasitic infestation.

Goats eat a wide range of native plants on acreage, but should still have access to free-choice hay so that they are not forced to eat less than desirable forage. Your goat may have an instinctual nature not to ingest harmful plants, but take precautions by walking your pasture and knowing the plants growing in it. Local authorities maintain lists of known poisonous plants in your region. Even nonpoisonous plants can be toxic if they’ve been sprayed with pesticides that are not within the realm of instinctual knowledge.

Goats on pasture, like any other animal, may be stalked and attacked by predators. Losing a prized goat or kid to coyotes, feral dogs, wolves, cougars, bears, and the like is heartbreaking. No two situations are alike in the most effective legal manner to cope with predators. Possible options for protecting goats might be a herd-protecting dog, donkey, or llama; stronger electric fencing; or hunting the predators. Always check local regulations before taking extreme action. Even though farmers have the right to protect their livestock, your problem predator might be a protected species.

Getting Your Goat

As you’ve already read, every goat needs a companion. This might as well be another goat, although a ewe, cow, or horse will suffice.

If a particular goat hasn’t already caught your eye and captured your heart, it’s time find the best stock that suits both the goat shed you’ve created and your budget.

One of the best places to find local breeders and receive third-party opinions is your feed supply store. The cashier or staff in these stores know the people who purchase goat ration and medications. They are generally happy to help a potential new customer and offer their opinion in the same breath. Just one name and phone number could open up an entire network of nearby breeders and goat husbandry associations for you.

While you are at the feed store, check the bulletin board—every feed store has one—for advertisements. If no such listing exists, become proactive and write up a quick “Goats Wanted” flyer and post it on the bulletin board before you leave.

Other viable options are the local classifieds, livestock auctions, and county fairs. Over the last few years, the Internet has grown enough to find nearby breeders or associations through any search engine. Type in your state plus the breed you seek. You should find hundreds of listings and your goat as the result of just one click.

Before you head out to a livestock auction with an empty trailer, please read the next section on assessing goats to avoid costly mistakes. You may luck out and find a beautiful animal at the auction at a decent price, but there is a substantial margin for error for new farmers. If you haven’t owned goats before, either take someone with you who that knows goats and specifically the breed you seek, or use your time at the auction to network with the men and women selling or buying goats.

Network with farmers and livestock sellers at auction and arrange a private showing of their available goats in their own environment.

Most sellers are happy to arrange a private showing at their farm at a later date. Trade phone numbers and give them a call in a few days. Networking is, in fact, the better option. You’ll make new friends who obviously share your interest and you might end up purchasing a special goat that a seller was apprehensive to sell to “just anyone.” Viewing a goat in its comfort zone allows you to observe the breeder’s housing arrangements and have ample time to chat and discuss registration, ancestry, and temperament, plus view any related barn records.

What to Look For

Price and paperwork aren’t all there is to purchasing a goat. Health, age, production (even just in ancestry), and temperament are all key considerations.

Healthy, good-natured goats are easily handled and show neither shyness nor aggressive tendencies. Healthy goats will be as interested in you as you are in them. If she isn’t looking at you with shining eyes and a sense of curiosity, you may want to move on to the next potential doe.

Know your breed. The body type should be a fair match to the breed you have chosen. Some goats have wide faces, some are without ears, others should fall within a certain height range by maturity. In all goats, look for a wide and strong back and chest, straight legs with trimmed hooves, and a clean, shiny coat. Avoid any goat with a sway back, a pot belly, bad feet, or a defective mouth.

The only way you’ll develop an eye for healthy, productive goats is to closely observe as many of them you can. Whether you subscribe to a goat magazine, spend time at county livestock judging sessions, or discuss conformation with a local breeder, you will soon build up enough experience to be able to distinguish a strong, healthy animal from an unproductive underperformer.

Goat Registration Terminology

On the day you buy your goat you might hear some new terms from the private seller or auctioneer. Apart from doe (female), buck (male), wether (castrated male), and kid (not-yet-weaned offspring), here are some other descriptive terms.

Advanced Registry—Pertaining to milk does. This goat has been noted and registered as supplying a decent volume of milk over the course of a year. Dependent on their current age and health, Advanced Registry does have a proven record of milk production.

Star Milker—Pertaining to milk does. The star system is based on a one-day test of milk volume with extra stars awarded for ancestry performance. Points toward stars are calculated by a complicated formula used by goat dairies and registries.

Registered Purebred—Comes with a traceable pedigree (much like a purebred dog comes with registration papers and a family tree).

Grade—A grade goat may or may not be a purebred animal. It is without papers and registration. If your goat meets certain requirements and you desire it, you might be able to register it as a “recorded grade” with the issuing authority in your area.

Americans, Experimentals, NOAs—These are grade goats. Americans and Experimentals are certainly not purebred animals, but an NOA (native on appearance) might be.

Registered Goats Versus Grades

Although registration offers some reassurance that the animal you’re buying is of notable heritage, it is not to be mistaken as a guarantee. A registered doe with an impressive ancestry may not be such an impressive milker. She might not even produce enough to keep the barn cat interested, or she may have trouble kidding, or both.

Registration papers matter most to those who plan to show, breed, or otherwise profit from the animals. If your strategy in raising goats is for personal use, the added expense and paperwork (now and in the future) are likely a waste of your resources.

Registration of a farm animal is similar to registration of a purebred dog—unnecessary for the average person’s needs. You can look at a dog and tell whether it is purebred without seeing the paperwork. You can make general assumptions of production, personality, and growth rate based on the breed. For personal or farm use, a dog’s registration is little more than paperwork to be shoved in a desk drawer.

The same theory holds true for goats. Some may disagree. They’ll disagree vehemently when trying to sell you a goat out of your price range while waving registration papers in your face.

Somewhere on your adventure of keeping farm animals you’ll discover your own comfort level and need for paperwork and registration. At the end of the day, no amount of registration beats trusting in the seller and your own ability to assess the age and health of an animal within reasonable doubt.

Keeping a Buck

You would do well never to keep a buck. Even though you will need to breed your milk does to keep their production up and your meat does to keep producing kids, there are better ways to accomplish the task than to keep a buck year round.

A buck requires separate housing, extra fencing, and twice as many chores. More often than not he is left in a shed of only adequate size and treated worse than a junkyard dog. Far too often I’ve visited or driven by farms and noticed unhappy bucks, isolated from all activity on the farm, in less than pleasant living quarters. Not only is this unfair to the animal, the buck’s story almost always ends in grief. A buck all but ignored will eventually become too aggressive to handle at breeding time, and will become stressed due to his lonely living conditions. Stress decreases an animal’s resistance to disease and does little for his breeding performance.

That same buck would be happiest on a larger farm with committed breeders who allow many does from many farms to be brought in for breeding.

Any change in a goat’s surroundings and routine will cause stress. Know your goat’s current feed program (right down to the very hour) and bring a week’s supply of her previous ration and hay home with her. For a few days don’t alter her old routine. If you need to make changes, do so slowly over the course of a few weeks.

The seller should supply you with the following:

• Registration papers (if applicable)

• Veterinarian contact information

• List of past medications and vaccinations

• Feed (ration and hay supply) for the first transitional week

• Hooves trimmed and horn buds removed (if applicable)

Most sellers will worm the goat twenty-four hours before you pick her up. This ensures that she does not introduce worms onto your land. If the seller has not wormed her, do so while you keep her in quarantine.

Kid goats can be transported in a pet carrier or dog kennel in the back seat of your car. I have seen people transport full-size goats in the back seat of the family car, but I wouldn’t do so unless the trip was twenty minutes or less and the route accommodated slow speeds.

The back of a pickup truck with a cap is perfect for transporting goats if you don’t own a livestock trailer. Add three to four inches of straw, cover any metal loops or clasps, and you’re set for the ride home. Take it easy on the turns and curves, and if your drive is longer than an hour, stop and check on the goat from time to time.

Quarantine any new goat for a week until the new surroundings become familiar and worming medication (if appropriate) has worked its way through her system. Slowly switch the feed over to your standard feed and spend plenty of one-on-one time with the new goat.

Goats are classified as ruminants and belong to the Bovidae family. They have a four-part stomach and will both graze pasture and browse woodland and brush.

In the wild, goats will eat leaves, branches, bushes, brush, and tree bark. They enjoy variety in their food and would rather reach up than chow down. Your goat may or may not have an instinctual ability to stay away from poisonous plants.

Contrary to popular belief, a goat will not eat everything in its path. Goats are prone to oral exploration and will mouth an object to experience it. Their interest in new adventures dictates that they must fully explore, rip at, tear apart, stand on, or conquer anything new to them. For their safety and that of your personal property, goats are not to be free-ranged around the homestead. Before you bring a goat home, take a look around and consider the potential trouble should they ever break free.

Feed Requirements

Goats require both hay (or pasture plus hay) and grain. If you are raising your goats for production you will want to be acutely aware of their nutritional needs and intake. You cannot assume a goat is fed nutritiously simply because it has filled up on brush, is on pasture, or has been given free-choice hay.

Goat ration is readily available at the feed store. The label will disclose added nutrients and vitamins as well as a protein count. A milking doe, for instance, requires 16 percent protein in her diet, while meat goats and wethers only require 12 percent.

Other nutrients may be required through supplemental feed. A prime example is selenium, a trace element required for the health of grazing animals but which has been depleted from the soil in some regions of the United States and Canada. Many feed manufacturers are aware of local depletion and have made up for this by adding selenium as a supplement to goat ration. Pay close attention to the labels and by all means collaborate with local herd owners or associations regarding supplemental nutrients.

Hay

Healthy goats won’t eat more than they require. Keep free-choice hay available at all times even when your goats are on pasture. A belly full of fresh pasture and nothing else could result in fermentation, excess gas, and the potentially life-threatening condition of bloat.

The average goat eats 3 percent of her body weight in hay each day. Based on an average square bale weighing 35 to 40 pounds and an average goat weighing 120 pounds, you’ll need approximately thirty-five to forty square bales of hay per year, per goat.

Kids and pregnant or lactating does will benefit from a higher-legume hay if you can find it. Legume hays are alfalfa, clover, soybean, vetch, and lespedza. Hay that is adequate for cows will not provide enough nutrients for goats. Cow hay is just barely suitable as bedding for a goat. You need hay fit for a horse or better. A 50-50 ratio of legume to grass is perfect.

The amount of hay you put out each morning or evening will vary through the seasons. It is completely normal for goats to eat the best part of the hay and leave half of the bale in the manger. Don’t let old hay sit in the bottom of the manger. Rotate it for a day perhaps, then delegate waste hay to bedding.

When you’re keeping goats, the biblical idiom “make hay while the sun shines” is changed to “store hay while the sun shines” for farmers on a budget. With two goats to care for you’ll be using eighty bales of hay throughout the year. Storing it on your own property as soon as it comes off the farmer’s field is both economical and wise. You don’t want to be scrambling for hay in February, paying a higher price per bale, and worrying about moving it around during freezing weather.

Every goat requires grain for good health, and goats in production even more so. Nutritionally designed goat ration (also called goat chow) exists to match a goat’s age, breed, purpose, and current condition. Every goat type, in fact every goat in your herd, will require a different amount of ration per day. Use the chart below as a starting point to determine your goat’s needs, then adjust quantities based on physical condition, seasonal changes, and the quality of hay you’re currently feeding. With minor adjustments throughout the year you will find the perfect quantity for every goat in your barn.

| General Ration Guidelines for Goats | ||

| Type | Condition | Daily Amount (in pounds) |

| Kid | Nursing | If interested, a bite or two |

| Weaned on pasture | ¼–½ | |

| Weaned no pasture | 1 | |

| Wethers/Open Dry Does | ½ (maintenance) | |

| Non-Dairy Does | Bred and Dry | ½–1 (maintenance) |

| 6 weeks before kidding | 1 (concentrate) | |

| Nursing | 1–1 ¼ (concentrate) | |

| 12 weeks after kidding | ½–1 (maintenance) | |

| Dairy Does | Bred and Dry | 1 (concentrate) |

| 2 weeks before kidding | Up to 3 (concentrate) | |

| Lactating | 1 plus ½ per pound of milk produced (concentrate) | |

Some quick adjustment guidelines per individual goats are:

• Decrease ration to goats on pasture, overweight goats, wethers, and dry (non-lactating) does.

• Increase ration to recently weaned kids, underweight goats, goats on pasture in bad weather, and pregnant or lactating does.

Water

Your goat needs fresh, clean water accessible at all times. No exceptions. The quantity goats consume will change with the seasons, their condition, and their present food supply. On average, one goat will consume one to four gallons per day.

As with hay, the best way to supply goats with water is head access only. Place water buckets outside of their pens where they cannot spill or soil them, but can easily get a drink. Empty and replenish water buckets daily, then sanitize weekly to prevent bacteria-related illnesses.

Extra Supplementation

Goats need a low level of acidity in their four-part stomach to maintain proper digestion. Grain and rich pasture may increase acidity and upset the balance. Increased levels of fermentation could prove fatal to a goat. Given the correct supplementary aids, a goat self-manages its acidic range without further intervention. Access to soda and salt is all that is required.

The average goat will consume two tablespoons of soda per day. Feed-grade baking soda is available at your feed store, but the grocery store version will get you through until your next visit to the feed store without harming a goat (it just costs more).

Salt is available in block form as well as loose. Request a trace mineral salt mix formulated specifically for goats. If not available, horse or cow salt mixes can be appropriate if they contain copper, iodine, and selenium (in regions that are depleted). Staff at the feed store or your veterinarian will know if your region is high or low in selenium and other trace minerals and if extra supplementation is required. Unlike excess protein, which harmlessly flows right through a goat, excess minerals can upset a goat’s healthy balance.

Maintaining Good Health in Your Herd

A goat can be kept healthy for most of her life by following standard barn practices of cleanliness, maintenance, and prevention. There will be times, though, when the cause of illness is so minimally within your control that you couldn’t have prevented it and your goat gets sick. Opportunities for the introductions of illness, parasites, toxic reactions, and bacterial infections are everywhere on a farm—there is no way around it. Learn to recognize the warning signs and take appropriate action when necessary. In my opinion, being overprotective of animals in your care is not a character flaw.

First Aid Kit

It took me a full year to wise up to the fact that keeping supplies and notes in a barn was a good idea. After multiple trips to the house and back gathering supplies to treat my animals, I eventually assembled a first aid kit for the barn. Once you’ve raised goats for a few years you’ll have your own favorites to keep on hand, but to get you started, here are the contents of my own kit:

• Rectal thermometer and isopropyl alcohol (to sterilize it)

• Three clean towels wrapped individually in plastic bags (to keep them clean)

• Antibiotic ointment

• Udder balm (for chapped udders)

• Deworming medication (watch the expiration date!)

• Hydrogen peroxide

• Tetanus antitoxin

• Mineral oil (for bloat)

• Propylene glycol (for doe ketosis)

• Electrolyte powder (for dehydrated kids)

Although you may not be one for keeping notes (and to be honest neither am I), forcing yourself to keep a barn journal may one day save your goat’s life. A reference of a goat’s change in eating habits, energy levels, or appearance is the best tool you can hand a veterinarian called in for diagnosis and treatment.

Barn records serve a secondary purpose. If you are ever called away or can’t get back home to do chores, any friend or neighbor armed with these records could walk into your barn and take over with minimal risk of adverse effects.

For each animal you might record daily ration amount, daily milk given, changes in eating habits, quarterly weight and temperature, last breeding date, hoof trimming dates, and vaccination records. Although warning signs of illness vary, you’ll know when your goat is not feeling up to par at a glance. Take note of the subtle changes and you may catch an illness, infection, or disease before it becomes life-threatening.

Any breeding herd should be vaccinated against enterotoxemia, chlamydiosis, and tetanus annually. If you vaccinate a doe four to six weeks before kidding, some immunity will be passed on to her kids. Based on your veterinarian’s recommendation, you may also vaccinate four to six weeks before breeding. Kids should be vaccinated against enterotoxemia and tetanus at two months of age, followed by a booster a month later.

It is also good practice to treat your goats for worms in the fall and spring. This may also require your veterinarian’s assistance. A fecal sample is submitted for assessment before treatment is prescribed or recommended.

Changes in Weight

Measuring and recording a goat’s weight monthly is good barn practice. Weight is a benchmark used to measure health, preparation for breeding, kid development, and if ration amounts require adjustments. A sudden drop in weight is the earliest signal that health is waning.

Weigh your goat again before medicating for illness or treating for worms. Too much medication could cause an overdose; too little medication and the treatment won’t be effective. To further complicate the matter, consistently underdosing literally trains organisms (bacteria and worms), to become resistant to the drug. Later on, even a corrected dosage will not be effective.

You can arrive at a quick approximation of weight using a measuring tape and the following chart. The measurement is taken from the goat’s heart girth, the area directly behind the front legs. If you are weighing kids with a heart girth of less than eighteen inches, use a house scale to weigh yourself first, and then again with the kid in your arms. Subtract your weight from the combined weight and you’ll have the kid’s weight.

Signs of Illness

Your goat’s mannerisms and appearance are the next telling signs of illness, infection, or disease. Some temperamental and physical warning signs might be:

• Lethargy

• Teeth grinding

• Coughing

• Shallow breathing

• Disinterest in ration

• Changes in manure color or consistency

• Change in milk color, quantity, or consistency

• Rough coat

• Dull eyes and/or change in color of the eye socket, gums, or facial skin (usually pink—watch for pigment changes to pale or blue)

Common Diseases and Illnesses

Some of the most common goat viruses and illnesses are listed on the following pages. For each listing I’ve tried to provide a preventive measure to help you maintain good health in your goats. In a few of the listings you’ll find that there are no known cures or treatments. Please check with your veterinarian for recommendations on any animal’s care. Cures and treatments are discovered every year, as are new diseases. If you have any concern over the health of a goat, take a temperature reading, isolate the animal in a quiet stall, and call the veterinarian.

Common Illnesses

Abscess

Firm to hard fibrous lumps under the skin of an animal caused by a bacterial infection of the lymph nodes. Most bacterial infections resulting in an abscess can be traced back to a flesh wound.

Prevention: Provide the safest yard and house for your goats. Metal protrusions from the ground, fences, and barn walls can cut through a goat’s hide.

Treatment: Isolate the goat from the herd and call the veterinarian to discuss severity. An expensive surgical operation might be required to remove the abscess.

Bloat

Bloat is a life-threatening, painful buildup of excess gas. If you see a growing swelling on the goat’s left side and the goat is very restless, don’t hesitate to place a call to the veterinarian’s emergency number.

Prevention: A change in diet or too much ration is usually the culprit. Keep grain and ration well out of a goat’s reach and introduce new foods slowly.

Treatment: While waiting for the veterinarian to arrive, try to keep the goat on its feet with the help of family, a wall of hay, or any other means. Rub the goat’s stomach area to help move and alleviate gas buildup. Drench the goat orally with two cups of mineral oil and follow up with a half cup of baking soda dissolved in room temperature water. Do not attempt this if you’ve never given a goat oral medication before.

CAE/CAEV

This deadly virus—caprine arthritis encephalitis—is still without a cure. The virus is passed from one goat to another and is easily recognizable by swollen and stiff knee joints in mature goats and weak rear legs in kids.

Prevention: Have your goats tested for the virus annually. Only purchase goats that are certified clear. Quarantine any new additions for at least a month and have your vet test the animal before releasing into herd population.

Treatment: None.

Chlamydiosis (Chlamydial Abortion)

This deadly disease is contagious to humans. If you are assisting with a live birth, wear long plastic gloves and scrub thoroughly after kidding. Warning signs are a premature abortion during the final eight weeks of pregnancy. If the doe carries the kids to full term, they are either stillborn or very weak.

Prevention: Part of your vaccination schedule.

Treatment: None. Discuss each doe’s future with your veterinarian and immediately remove affected does from the herd to prevent spreading the disease.

Coccidiosis

A potentially life-threatening parasitic infestation. You’ll notice a lack of appetite and energy. Your goat may lose weight quickly or develop bloody droppings. Cause of coccidiosis is a protozoal parasite.

Prevention: Keep the goat house, feeders, and watering stations clean.

Treatment: Coccidiostat available at most feed stores or through your veterinarian.

Diarrhea/Scours

The trouble with scours and kids is that they will very quickly become dehydrated and too weak to feed. Scours are often brought on by a change in diet, but could be the signs of other problems.

Prevention: Keep the goat house, feeders, and watering stations clean. Pregnant does may be vaccinated to assist in the prevention of scour-causing illnesses.

Treatment: Isolate any kid with scours immediately. Disinfect every bit of your barn or goat shed. Call the veterinarian for advice and bottle-feed electrolyte fluids to any affected kid (available at the feed store) instead of milk ration for two days.

Enterotoxemia

Classified as a life-threatening bacterial infection. This condition is also called overeating disease. Goats are seen to twitch, show signs of bloat, grind their teeth (a sign of pain in goats), and have an increase of temperature.

Prevention: Part of your vaccination schedule. Avoid changes in diet.

Treatment: None.

Hoof Rot

If there were one good reason a goat’s yard and bedding should always be dry, hoof rot would be it. This bacterial infection can result in death, but you’ll notice it and have time to treat it well before that happens. Symptoms are smelly feet, lameness, loss of weight, and potentially tetanus.

Prevention: Trim hooves regularly. Keep bedding clean and yard dry.

Treatment: Trim away hoof to a consistent length and to healthy tissue. Soak the foot for two minutes in water with dissolved copper sulfate (at a ratio of one gallon water to one half pound copper sulfate, respectively). If the condition is severe, consult with your veterinarian for antibiotic treatment.

Internal Parasites and Worms

Repeated pasturing in one area without rotation is the main cause of repeated worm infestation. The goat consumes worm eggs in the grass, and they hatch and mate in the stomach and then lay eggs in the intestine. The eggs are released with every bowel movement, the grass grows, and the eggs are consumed again.

Although completely natural and an inescapable part of life, parasitic infestations can drag a goat’s health down with poor appetite, coughing, reduction in or strange-tasting milk, and weight loss.

Prevention: Rotate pasture. Keep all feed and water dishes meticulously clean. Follow your veterinarian’s suggested worming schedule based on available pasture and regional climate.

Treatment: Have your veterinarian test a fecal sample and provide medication.

Ketosis (Pregnancy Toxemia)

Ketosis is a metabolic disorder that could be life-threatening. Usually brought on by feed quality not matching a doe’s condition (age, breed, weight, health) and her body starts giving of itself to facilitate fetal growth. Most often seen in does a few weeks prior to, or just after, kidding. The doe goes off her feed, may appear lame, and may have sweet-smelling breath or urine.

Prevention: Follow a responsible feeding schedule with bred does. Ensure that the feed supplied is of the highest quality and is offered free-choice. As fetal growth draws energy and nutrients from the doe, and less space is available within the doe’s stomach, she cannot consume large amounts of feed at a given time. Does that were overweight before breeding and then fed a nutrient-lacking diet are more susceptible to ketosis, but it is also common in first-time mothers and does carrying multiples.

Treatment: If you catch ketosis in time (by noticing that the doe’s not eating), add a feed-grade dry molasses to her ration or concentrate to entice her to eat. Separate her from the herd to monitor her fluid intake. You need to ensure she gets some type of energy (in the form of sugars such as molasses or propylene glycol) and sufficient water to flush the ketones out of her kidneys. Ketones are the byproduct of the doe’s system metabolizing fat into glucose. If she worsens, call the veterinarian.

Consistent scratching and biting, loss of weight and hair, and decreased milk production could be warning signs of a lice infestation—especially if your goats are currently living in a damp environment.

Prevention: Keep living quarters dry and avoid contact with infested animals.

Treatment: Any powder, dip, spray, or pour-on insecticide approved for livestock or dairy animals will work and should all be available at your local feed store.

Mastitis

A painful bacterial udder infection for does. Your doe may stop eating. Her udder may be hard, swollen, or abnormally hot or cold. Her milk might smell bad or show signs of blood.

Prevention: Keep living quarters clean, dry, and safe. Apply a teat dip after every milking session. Once a month, check your does with a mastitis test available from your local feed store (dairy cattle tests work fine for goats).

Treatment: Based on your veterinarian’s recommendation, antibiotics might be in order. Milk the doe three times a day to relieve pressure and apply hot packs to the udder four times a day. Isolate from herd. Dispose of her milk if antibiotics are used, and consult with the veterinarian for a clear date.

Orf

Also known as sore mouth, scabby mouth, contagious pustular dermatitis, and ecthyma. This viral condition causes thick scabby sores on the lips and mouths of kids and may last up to four weeks. Kids may have trouble nursing and as a result could suffer malnutrition. Nursing kids with orf can pass the infection onto the teats of a doe, which can quickly escalate into mastitis. Your veterinarian may suggest quarantine of nursing kids with does and a sterilizing teat and udder wash four times per day for at least four weeks after the first signs of orf.

There is a human health risk associated with this virus. Wear rubber gloves and sterilize all equipment thoroughly.

Prevention: There is nothing you can do to prevent this virus.

Treatment: An after-infection, veterinarian-supervised vaccine is now available to prevent further incidence.

Pinkeye

Caused by bacteria or virus. Goats will squint and have watery eyes.

Prevention: Contagious. Avoid contact with infected goats.

Treatment: The entire herd should be treated with antibiotic drops.

Pneumonia

Various bacteria and viruses attack an already stressed or ill goat. May also be brought on by unrelated allergic reactions. Warning signs are coughing, loss of appetite, fever, and runny nose and eyes. Drafts and wet living conditions exacerbate the potential for pneumonia.

Prevention: Keep your goats as stress-free as possible. Ensure their housing is free of cold drafts.

Treatment: Call your veterinarian for antibiotic treatment.

Ringworm

Ringworm is brought on by fungi in the soil that attacks the skin of an animal. It shows up as circular skin discoloration resulting in hairless patches on the head, nose, neck, or udder.

Prevention: Highly contagious to both animals and humans. Avoid contact with infected animals.

Treatment: Wear rubber gloves and follow a strict sterilization practice. Scrub the patches with warm, soapy water and coat with iodine or fungicide available from your local feed store.

Scrapie is a neurological disease (similar in nature to mad cow disease) that has been under steady investigation since 1952 to determine cause and discover a cure.

Only seven cases have been reported in goats, and in all cases the disease has been acquired from contact with sheep. Further information on scrapie can be found in the sheep health section of this book, on the Internet at www.keepingfarmanimals.com, or (if in the United States) by calling the USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service at (866) 873-2824.

Tetanus

Harmful bacteria enter through a flesh wound and create stiff and spasmodic muscles. Early warning signs are wide eyes and flared nostrils.

Prevention: Part of the kids’ vaccination schedule at four weeks and then eight weeks of age.

Treatment: Detected early, tetanus can be halted with veterinary care and medication. Advanced cases are without cure and result in death.

Ticks

If your goats pasture and browse in wooded areas, ticks may be a problem—for both you and your goats. You may find them rubbing or scratching the tick’s point of entry as well as losing hair and weight. Check forest-pastured goats daily during tick season in your region and remove any you find immediately.

Wounds

Goats are prone to cuts and scrapes due to their curious and adventurous nature. Although the cuts themselves aren’t much of a problem, the introduction of diseases and infections through flesh wounds can be life-threatening. Knowing how to sanitize and treat those wounds immediately and routinely is a necessity.

Treatment: Clean the wound with hydrogen peroxide. Stop any bleeding by applying pressure with a clean towel. Clip hair around the wound and flush the area with warm, soapy water. Rinse with clear water to remove any soap residue, apply hydrogen peroxide once again, and cover the area with an antibiotic ointment. Every day check, clean, and redress the cut until it is fully healed. If the wound becomes infected, call your veterinarian immediately.

GOAT VITAL SIGNS AND GROWING CYCLE

• Rectal temperature: 101.5 to 105 degrees Fahrenheit

• Pulse rate: seventy to eighty beats per minute

• Breathing rate: twelve to twenty breaths per minute

• Puberty: At five months to a year of age, dependent on breed

• Average birth weight: eight pounds

• Average gestation period: 150 days

• Heat cycle: every eighteen to twenty-four days

• Heat period: approximately one day

Grooming

A hoof trim is one maintenance task that doesn’t take much time but is absolutely necessary to your goat’s health. Without proper hoof care your goat can become sick, lame, or permanently crippled. Frequent attention to hoof care, no matter how minor, is decidedly easier than infrequent major trimming. From the age of two months I make all goats stand and allow inspection, or a trim, of their hooves every month.

If you pasture your goats like I do (on somewhat rocky pasture) the hoof will wear down naturally, which minimizes the monthly task. Goats restricted to a small yard seldom have that opportunity, but the addition of a small concrete slab or a stack of large rocks to climb on will help them maintain their hooves and lighten your chore load.

Confine each goat in a manner that prevents escape. A dairy stand with stanchions, leash and collar tied to a barn wall or fence, or a helpful friend are all great ways to keep a goat confined for a few minutes. If your goat is being particularly difficult, lean your shoulder into her side with her other side against a wall while you work on each hoof. Angoras and kids can be “sat” on their rumps, leaning against your legs while you work.

Stay calm while you work and you will find that your goat remains calm as well.

• Wear gloves.

• Bring shears, a rasp, and hydrogen peroxide to the barn with you.

• Soft hooves are easier to trim than dry hooves. Allow your goats an hour in the yard, as hooves are softened by morning dew.

Providing rocks in the goat yard gives them a play area as well as diminishing the need for too-frequent hoof trims.

• Constrain the goat in a manner that allows you easily and comfortably to bend the goat’s leg for observation of, and work on, the entire bottom of the hoof.

Step 1: Gently scrape out any impacted dirt in the curve of the hoof with a hoof pick or the point of closed shears. Work gently inside the wall. Impacted dirt at the toe of the hoof does not need to be forced out. Get the debris that falls out easily as you trim. It will all have fallen away by the time the hoof is trimmed.

Step 2: Snip away the overgrowth at the toe of the hoof (it will be the longest), then move on to the sides and remove any folds or excess found there. Your objective is a level foot—a hoof wall that just barely extends and protects the frog.

Step 3: Use a hoof rasp to create a smooth finish on the hoof wall.

Should a goat arrive on your farm with a severely overgrown hoof, only take a little off at a time every five to seven days. It may take a month, but eventually you will have a neat and trim hoof.

If you happen to snip too far and your goat bleeds, clean the wound with hydrogen peroxide and check daily for signs of infection.

The anatomy of a hoof.

A nicely trimmed foot. The base of the hoof is parallel to the coronary band (the area where the hair ends and the cuticle begins).

Milk from a doe that has proper care tastes so similar to cow milk that most people would be hard-pressed to tell the difference. Even though only a fraction of North Americans know that goat milk is palatable, more people worldwide drink goat milk than any other milk.

In the milk industry, goat milk is never measured in gallons or quarts but by weight. Small herd farmers just keeping a few goats for personal use, however, continue to measure their daily supply in standard liquid measurements. A good milk doe can supply your home with nine hundred quarts of milk over the course of a year. Some dairy breeds are known to give milk that is rich in milk fats, making it perfect for creating a variety of cheeses in your own kitchen.

Milk Production Management Issues

A goat’s milk production is dependent on the kidding cycle. Peak production is two months after kidding, but a good dairy goat continues to produce milk long after her kids are weaned.

When a doe first gives birth, her body begins producing milk. The term for this is “freshening.” For the next eight weeks her supply increases, levels off for four months, and then begins decreasing until she is bred again.

Standard small-herd practice is to breed the milkers once per year, dry them out for two months previous to kidding, and breed them again. If you follow that strategy, most does will supply you with milk for 240 to 300 days of the year. If your doe dries out early—only supplying milk for eight months or so—she’s still a good milker for any family.

Your doe will be at the height of her production in her fourth and fifth years. Negative factors affecting milk production are stress, insufficient natural or artificial lighting, weather, injury, feed quality, illness, or major disruptions in their routines. Milk does thrive on routine and goats require milking twice per day. You get to set the time, but for best results remain consistent with their schedule and keep milking sessions about twelve hours apart.

Equipment and Supplies for Milking Goats

Although you could get by in a pinch with a high-quality stainless steel bowl from your kitchen, a cheap milk strainer, and some quart canning jars, you will be milking twice a day for at least 250 days a year, so you might as well have the proper equipment.

Equipment for Milking

• Milk stand (with or without stanchions)

• Clippers and a brush to trim and brush hair away from back, sides, and udders to prevent hairs shaking down into the milk

• Udder wash to remove any debris and to sanitize hands

• Small bowl or mug used as a strip cup (squirt in the first milk from each teat for a visual quality check.)

• Stainless steel milk pail

• A made-for-goats teat dip to prevent bacterial infections

• Bag balm (to prevent chafing or chapping of the udder and teats)

• Notebook to record milk amount from every session

• Dairy strainer with disposable milk filters

• Milk scale for weighing milk per session (I don’t personally use these.)

• Home pasteurizer (pasteurize milk yourself with a double boiler and a candy thermometer. Heat milk to 165 degrees Fahrenheit and maintain for 30 seconds.)

• Glass milk jars

• Chlorine bleach

• Stiff-bristle (plastic) brush

• Dairy acid cleaner

A relatively skilled carpenter can create a simple milking stand including stanchions in just a few hours and with less than one hundred dollars’ worth of lumber. Goat stanchions can also be purchased online—new or used.

Sanitize all equipment before and after milking, including udder, teats, and hands, to ensure a healthy, happy doe and high-quality milk.

To sanitize equipment between uses, first rinse in warm water to remove fat residue. Next scrub with a bristle brush using hot water, dish detergent, and an ounce of chlorine bleach. Rinse in clear water and then in a dairy acid cleaner. Never use dishcloths to wash or towels to dry. These items, even fresh out of the laundry, are loaded with bacteria. Allow your equipment to drip dry.

A homemade milking stand offers stanchions (to hold the goat’s head in place), a sturdy stand for the goat, and even a small sitting area for the milker.

How to Milk a Goat

When it comes right down to brass tacks, farmers have been milking goats for centuries without all the fancy equipment. I’m half embarrassed to tell you my own story, but I want to make a point about getting by with what you have. Picture this: A doe and her needing-to-be-weaned kid landed in my barn and I, knowing nothing other than the rules of sanitation and pasteurization, proceeded to milk her twice daily.

She was young and small, and in retrospect I guess she had been bred too young. This worked in our favor, though, as she had never given milk and I had never taken it. She would not stand idly on the barn floor and let me milk her. I had never heard of a stanchion, but I was determined that she stand without fussing or kicking over the bucket. The only way I could hold her in place by myself was to lock her head between my legs, bend forward across her back, and milk her. I did this twice a day, every day, for a month before I started asking around for advice.

Although that method is neither conventional, efficient, nor 100 percent effective, we still drank healthy, delicious milk every day. Today I have a milking stand.

The Milking Process

There is a rhythm to milking a doe. You can learn it just by watching the kids. Bump. Lock. Draw.

Once you have positioned your doe, prepare her for a milking session by brushing her coat to prevent hair from dropping into the milk pail and wash her udder and teats with a teat dip. With your milk pail in place, lock your forefinger and thumb around a teat at the base of the udder and draw down. Never squeeze her udder, only her teat.

There will be milk waiting in the teat, which you will guide out with a squeeze, drawing downward, not pulling downward. If the difference doesn’t make immediate sense to you, think of how you might squeeze all of the toothpaste out of the tube with only one hand. Better yet, imagine guiding your doe’s milk along a straw, softly pushing it down, one finger tightening at a time.

After a full draw down and into the bucket, release the pressure on your top two fingers to allow more milk to enter the teat, and draw again. Release. Each time that you release your grasp the teat fills up with milk again.

Many first-time farmers will not get any milk out of the teat on their first try. Don’t worry if this happens to you. The cause is most often an inadequate pressure at the top of the teat so the milk moves back up and into the udder instead of along the teat and into the bucket. Squeeze just a little tighter at the top of the teat and try again.

A few tries and you will have it. Your doe relaxes and you can move on to learning how to milk her with both hands in an alternating left-right-left-right fashion.

When the flow stops you can give a gentle bump to the udder with your hand still wrapped softly around the teat. Then tighten-squeeze-release once or twice more.

Before releasing your doe, cover and set the milk pail aside, then quickly dip and dry her teats and massage in a small amount of bag balm. You’ll be hastening to the house to filter and cool the milk even if you choose not to pasteurize. Pasteurization is fully described within the dairy cow chapter.

Unpasteurized Milk

For a host of reasons some people choose not to pasteurize their milk. If you’ve decided this method is for you, filter the milk immediately and begin the cooling process. Don’t expose the milk to sunlight or fluorescent light during the cooling process. The basic rule of thumb is that goat milk should be cooled from 101 degrees Fahrenheit (at time of collection) down to 38 degrees Fahrenheit within one hour of milking.

Never add new milk to old milk or warm milk to cooled milk.

Excess milk can be frozen in glass containers. When you need the milk, simply let it thaw in the refrigerator for twenty-four hours, shake it up, and it is ready for use. If you notice a change in flavor after freezing, use it for baking or to make cheese, butter, or soap.

Fiber Goats: Combing Cashmere and Shearing Angoras

The down-like hair that grows in small clusters under the main coat of a goat is cashmere. You will only see it if you live in a northern climate. As stated in the breed section, many breeds are capable of producing cashmere, but not many produce enough quantity to make collecting it worthwhile.

Cashmere can be obtained through shearing, but most of us with just a few goats opt to comb out the cashmere instead. Daily combing for fifteen to twenty consecutive days right before the goats’ own bodies start shedding the hair in mid-December is required for the highest yields.

Save collected fibers in a cardboard box or paper bag without the long primary hairs that your comb picks up. Expect to collect anywhere between one-third and one full pound per goat.

Angora goats create enough fiber to make the process viable through shearing. An Angora goat’s short fibers are mohair. The longer fibers are called kemp.

Yearlings give the finest hair and yield the highest price as their mohair is used for clothing. Shearing isn’t a rite of passage—any kid with four-inch-long hair can be sheared. Adult hair is used in carpets and upholstery. The average doe, buck, or wether hair is four to six inches in length and grows approximately three-quarters of an inch per month.

Shearing of Angoras is performed just before kidding (in early spring) and then again in the fall (between weaning and being rebred for the next season). It is important not to procrastinate on the second shear of the year. Angoras need ample time to regrow their coats before the weather turns cold.

You could shear your goats yourself or hire a professional either to train you on technique or to shear your goats for you. A few days before shearing, clean out the barn, bring the goats in, and keep them dry. Wet mohair is not only difficult to remove, it is also prone to mold during storage. You do not need to wash and dry the fleece before sale, but you could net a higher price if you do.

If you have kids, shear them first on a clean workspace. Have a helper on hand to pick short hairs and any irregular, stained, or matted clumps out of the fleece. Then roll each fleece inside out and bag it individually in a cloth bag, paper bag, or cardboard box. Tag each package with the goat’s name so you can record and track fleece weights from season to season. When you are finished with the kids, sweep the area clean and follow the same guidelines with the adults.

After shearing you may need to keep your goats inside for a full thirty days (the average length of time to grow three-quarters to one inch of hair) if the weather is harsh. Complications of exposure are sunburn, hypothermia, or pneumonia.

You can expect three to four pounds of the finest hair from a yearling and six to twelve pounds per shearing from an adult Angora.

Goat Meat

Gram per gram, goat meat is lower in calories, fat, saturated fats, and cholesterol when compared to beef, pork, lamb, and even to skinless chicken. (USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 20, 2007)

Goat meat is also known as chevon (meat from a young, but mature, goat), cabrito or chevrette, (meat from a milk-fed kid) and chivo or mutton (meat from an older goat). The flavor and tenderness of the meat is similar to wild venison—the most coveted coming from a young animal—and can be prepared in stews, as steaks or burgers, or a dinner roast.

As you’ve read in the strategy section on raising goats (above), goats vary in their sizes and growth rates across the breeds and crossbreeds. You can count on fifteen pounds of freezer meat from the youngest dairy goat up to sixty-five pounds from an eight-month-old Boer.

Breeding, Kidding, and Care

Even though your doe might think she is ready to breed at six months of age, don’t allow it until she is at least eight to nine months old. A better measurement is to wait until she has reached at least 80 percent of the average mature size for her breed. If bred too young, a doe’s growth will be stunted, and she’ll have less chance of future multiple births.

Milk goats are bred every year, usually during September and October. After a five-month-long gestation they give birth at the start of spring, when fresh pastures naturally provide the most nutrition. Meat and fiber goats are often bred every eight to nine months with the optimum breeding time between August and October. Angora goats are bred between August and November, right after a fall shearing to ensure they’re ready to kid right after the spring shearing. Goats raised for cashmere are bred well before November. All kids should be weaned by mid-June, as lactation slows the growth of cashmere.

Finding a suitable buck can be challenging. Although goats are gaining in popularity, not many people keep bucks on hand for breeding. If you keep specialty goats and want kids to keep, register, or sell for any purpose other than meat, the qualities you desire in a buck may not exist within a day’s drive.

With dairy breed bucks, look for owners who keep good barn records on ancestry. A dairy breed buck will pass on the genetics of his dam if a doeling is produced. Furthermore, if your doe is polled and she breeds with a polled dairy buck the offspring will only have a 50 percent chance of fertility.

If you are only breeding to freshen a dairy doe and aren’t planning on keeping the kids long-term, any healthy buck of any breed and comparable size will do.

Bucks and Breeding

A buck should be wormed and in excellent health. He should also have been on a concentrate ration for at least two months prior to breeding. Ask to see the buck’s immunization and vaccination schedule. Check carefully for a CAE/CAEV clear certification.

Steer clear of bucks with poor conformation, bad legs, or improper hoof care—no matter what registration or paperwork is shown and even if you only plan on raising the kids for meat. A buck with a dull coat, very thin hair, or with patches missing may have lice, ticks, or ringworm—which will all be passed on to your doe.

A ready-to-be-bred doe will stand quietly by a buck when placed in the same area. A doe who is not ready will repeatedly move away at his every advance. A buck may mount a doe several times during breeding. Successful mating is noted by the extreme arch in the buck’s back upon completion.

If you will be registering the kids, ask the buck owner for a service memo. The information you’ll need for registration includes the date of breeding, the names and registration numbers of the doe and the buck, both owners’ names, and the buck owner’s signature.

Artificial Insemination