THREE

SACRED SIGNS

|

THREE |

Like many people who have visited Egypt, I own a souvenir necklace with my name spelled out in hieroglyphs on a pendant shaped like a cartouche, as the knotted rope ring that surrounds royal names is known. I confess that I have only worn it a few times, and never wore it again after someone I had never met before addressed me by my first name in a public place. I had forgotten that I was wearing the necklace, announcing my identity to anyone who could read a few Egyptian hieroglyphs – which is more people than you might expect. How different from the situation two centuries ago, when the most basic understanding of hieroglyphic signs had been lost for several centuries.

The cartouche emblazoned with my name used symbols that corresponded, one by one, to a single sound value, or phoneme: k, r, i, s, t, i, n, a. Since my name derives from Greek, there is no ancient Egyptian equivalent; it is a foreign word that can only be spelled out sound by sound. The same principle applied to the two cartouches that would help Thomas Young and Jean-François Champollion work out how to read Egyptian hieroglyphs in the early nineteenth century, by identifying familiar Greek names – Ptolemy and Cleopatra, king and queen of Egypt just after 200 BC – that were spelled out the same phonetic way in cartouches: p, t, o, l, m, i, s and k, l, i, o, p, t (or d), r, a. This was a revelation, because all the birds, body parts, geometric shapes and squiggled loops and lines used as Egyptian hieroglyphs had long been assumed to bear purely symbolic or philosophical meanings, rather than representing something so straightforward as a sound. Steeped in the ideas of the European Enlightenment, with its roots in the Renaissance, scholars reasoned that if they could decipher hieroglyphic writing, the lost wisdom of ancient Egypt and Hermes Trismegistus would be restored to them, repairing the memory loss that the historical divide between Islamic Egypt and Christian Europe had created.

Lost wisdom, mysterious symbols: quite a lot was riding on being able to read the copious inscriptions with which ancient Egyptian sculptors had covered temples, obelisks and statues, or that scribes had inked in black and red on the surfaces of papyrus scrolls. Among the Egyptian antiquities the British army seized from French troops at their 1801 surrender was the chunk of dark grey stone bearing the names of Ptolemy and Cleopatra that proved pivotal for both Young and Champollion. On one face, the stone bore tightly packed rows of inscription in three scripts and two languages: Egyptian written in the Demotic script, Egyptian hieroglyphs and Greek. Its significance had been obvious to the French officer who oversaw its removal from a defensive wall at el-Rashid in the western Nile Delta, better known in European languages as Rosetta.1

This chapter explores how hieroglyphs and other writing systems functioned in ancient Egypt, and how (or whether) the ancient language was ever ‘lost’. We start at the beginning, with the invention – for that is what it was – of the hieroglyphic writing system in the Protodynastic period when a centralized state headed by a king first emerged in the Nile Valley. Several languages and writing systems were used in ancient Egypt, and understanding literacy rates and the social uses of writing is important for understanding how language use evolved during the Ptolemaic, Roman and Byzantine eras. In the medieval Arab world, Egyptian hieroglyphs were just as fascinating to many scholars as they would prove to be in early modern Europe. Islamic scholarship on hieroglyphic writing has been little known in the West, however, even though it was one source used by the seventeenth-century Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher in his own studies of Egyptian inscriptions. Kircher’s mystical interpretations emphasized the sacred and symbolic character of the signs, and it was only the much later insights of Young and Champollion, both of whom had studied many ancient and modern languages, that convinced European scholars of the Egyptian language’s more mundane aspects. Like every language, ancient Egyptian had grammar, syntax and vocabulary. It just expressed these in a writing system that depicted animals and everyday objects, instead of using more abstract characters or cuneiform wedges. In the past 150 years Egyptology has systemized an approach to reading, recording and analysing ancient Egyptian texts. Many of these do concern the mysteries of the universe, or something along those lines, but just as many are government edicts, adventure stories and mortgages. The concerns of ancient Egyptian society became a little more clear – but as it turns out, no less complex.

Any mention of the Rosetta Stone invites talk of keys, codes and decipherment, as if we still suspect that the ancient Egyptians were hiding secrets from would-be readers. There is, in fact, something to that. Today, living in societies with near-total literacy, we assume that writing something down means that anyone can read it. But this is a relatively recent phenomenon, and by no means a universal one. In societies where few people can read, writing and, crucially, the display of writing can reinforce the authority held by ruling institutions, like the Christian Church in medieval Europe. Estimates suggest that only between 2 and 5 per cent of the population in ancient Egypt could read and write at any period, and not all of those individuals would have full command of the different scripts in use. Imagine yourself in a room full of 100 people, having to rely on just two or three of them to write an email, draw up a loan agreement or read out a government notice. Much would depend on trust.

The very word – hieroglyphs – that ancient Greek writers applied to Egyptian picture-writing had the literal meaning ‘sacred carvings’, and this itself offers a clue as to the use of the pictorial writing system familiar to us today, with all its birds and body parts. Hieroglyphic writing did have a sacred character, in that the ancient Egyptians used it almost exclusively in contexts evoking the divine world: on coffins and statues, in tombs and temples, or on high-status jewellery, furniture and weaponry like that found in the tomb of Tutankhamun. Hieroglyphs were formal, like the best italic calligraphy. They were also closely connected to the distinctive system of representation used in Egyptian art, which suggests that hieroglyphic writing developed at the same time as methods for drawing and carving other kinds of images. Writing and art go together in ancient Egypt: both favour profiles for clarity in representing faces and limbs; both scale objects up or down to show relationships of status, or to help signs fit together; and both obey rules of orientation, so that all signs and images face in the same direction. Having all the signs facing the viewer’s right (most obvious for human and animal figures) was the dominant orientation, and since Egyptian is conventionally written from right to left, like Arabic and Hebrew, the reader ‘faces’ the human and animal signs. But hieroglyphs could also be reversed, reading left to right, where a decorative scheme required it, for instance to create a symmetrical composition or to make both walls of a tomb ‘face’ an offering placed at the far end. The same held true for other twodimensional images, although statues, and other three-dimensional figures, always represented men (rarely, women) with the left leg advanced, regardless of where the statue would be placed or how the object would be used.

Hieroglyphic writing appears around 3200 BC in the late Predynastic or Protodynastic period, at the same time as a sudden and significant change in art. It is probably not too strong to speak of these new visual forms as having been invented to suit the needs of the rulers of the new Egyptian state. The decorated pottery, small stone palettes for grinding cosmetic paint, and slender, almost cylindrical, free-standing sculpture of preceding centuries gave way to novel or scaled-up object forms that could exploit the potential of the new pictorial representation in full. On an oversized, double-sided cosmetic palette depicting king Narmer, images of the king and his entourage obey the core principles that Egyptian art would adopt for more than 3,000 years. Likewise groups of hieroglyphic signs are readily legible, like the name of the king (‘fierce catfish’) at the top of the palette, inside a square, patterned frame representing the royal residence. Writing went hand in hand with the creation of a centralized state because it filled a bureaucratic need for keeping records of transactions and for labelling raw materials and processed goods. At the same time, their decorative value and restricted use also made hieroglyphs well suited to the ceremony and symbolism of Egyptian kingship.

Most hieroglyphic signs have a phonetic value, that is, they represent a sound produced in speech. Some signs, like those used to spell my name, or Cleopatra’s, in a cartouche, represent a single sound, others two or three sounds together. In addition to the hieroglyphs that write the sounds of a word, other hieroglyphs may indicate gender (male/female), number (singular or plural) and the specific sense in which the word is being used.2 This last sign, which Egyptologists call a determinative, appears at the end of a word and helps clarify its meaning, where two or three similar meanings might be possible, or classify the qualities of the idea being expressed. The determinative of a sparrow, for instance, classified words that had negative associations, or signalled smallness, while the determinative of two human legs indicated anything to do with motion. Not every hieroglyph was pronounced (determinatives never were), and not everything that was pronounced had a hieroglyphic sign. True vowel sounds were not written down, probably because these sounds changed when the tense or number of the word changed. The reader would know what vowel sounds were needed, so that writing only consonants (or near-consonants, like ‘o’ and ‘y’ sounds) made perfect sense. Modern Arabic and Hebrew work in a similar way, often omitting vowels in written form. Ancient Egyptian belongs to the language family known as Afroasiatic or Hamito-Semitic. Although it has many distinctive features, it also has a number of similarities both with Semitic languages, such as Hebrew, Arabic and ancient Akkadian, and with North African (‘Hamitic’) languages, such as Hausa (spoken in Niger and Nigeria) and Berber (spoken across the Sahara).

Hieroglyphs were only one of the writing systems used in ancient Egypt. When scribes wrote on sheets of papyrus, using ink and a reed brush, the action suited a more flowing form of script. Reducing the hieroglyphic signs to outline forms that could be written more smoothly and rapidly yielded a script the Greeks called hieratic, meaning ‘priestly’, although in fact hieratic had much wider and more commonplace use. Hieratic could be written in a decorative style suited to prestige documents like wills or Book of the Dead papyri, but it tended to serve more run-of-the-mill purposes, for instance in contracts, letters and receipts. Hieratic script was the engine of Egyptian society for much of its ancient history, the everyday writing that village scribes or temple copyists deployed for legal and administrative purposes, or to make new versions of library scrolls that were wearing out. Boys training to be scribes, who were taught to read and write in schools attached to their local temples, would have learned hieratic first, not the more specialized hieroglyphic script that students of ancient Egyptian start with today.

Languages change quickly as they are spoken, but writing systems tend to lag behind, replicating a more staid form of the language that suited certain contexts precisely because of its age and authority, rather like the early seventeenth-century phrases of the King James Bible that resonate when recited in some church services today. The hieratic script was better than hieroglyphic writing at keeping up with language change. Egyptologists divide major shifts in the grammar and vocabulary of ancient Egyptian into Old Egyptian, Middle Egyptian and Late Egyptian, although unlike the similarly named time periods of Egyptian history, these stages do not always follow each other in sequence. Middle Egyptian was used for hieroglyphic inscriptions, especially in temples, as late as the Ptolemaic period, while Late Egyptian, which was roughly the language king Tutankhamun spoke around 1325 BC, survives chiefly in hieratic. From around 650 BC a stage of ancient Egyptian known as Demotic came to be written down in its own script, an even more reductive form than hieratic. This is the script that appears in the middle of the Rosetta Stone, where it is more fully preserved than either the hieroglyphic or Greek texts. The Demotic form of Egyptian was only ever written in Demotic script, and vice versa. Surviving Demotic texts include everything from marriage contracts to abstruse religious discussions: thousands of papyri still await translation, since few scholars specialize in Demotic today.

Demotic flourished at a time when Greek had become the main language of the state, yet it is almost entirely free of vocabulary borrowed from Greek, as if Egyptian priests and scribes, who were responsible for composing and writing down Demotic texts, had made a conscious choice to exclude foreign words. Instead, the form of Egyptian spoken in Ptolemaic and Roman times is what we know as Coptic, which continues to be used as the language of the Coptic Christian church liturgy in Egypt. The Coptic script appeared in the first century AD, using the Greek alphabet of 24 letters plus an additional eight letters for Egyptian sounds not represented in Greek. Coptic thus could write some of the vowel sounds and shifts that scripts derived from hieroglyphs did not; it also lacked the other scripts’ links to Egyptian religion, which became an important consideration as more people converted to Christianity in the Roman and Byzantine eras. In contrast to Demotic, Coptic owes a substantial part of its vocabulary to Greek, perhaps as much as 40 per cent. Both languages were spoken in Egypt until around the sixth century. After the expansion of Islam and Arabic-speaking culture into Egypt in the seventh century, Arabic and Coptic coexisted for centuries, although each gradually (though not exclusively) became associated with the Islamic and Christian religions many of their speakers practised. Language diversity was always present in Egypt, as it is in many societies today. Bilingualism or multilingualism, and using different languages for different purposes, would have been a feature of life for many people in ancient Egypt, long before the changes introduced by Hellenistic Greek rule. In the New Kingdom, for instance, Akkadian was the language of international diplomacy, as we know from discoveries of cuneiform tablets sent between Egypt and Iraq. Minority languages and regional dialects have not survived in written form, however, making ancient Egypt appear to be a more homogeneous society than it actually was. Writing conferred power, and it was the power of hieroglyphic writing in particular that tantalized, especially as it fell ever further out of use.

A census taken in the early second century AD, in the provincial capital Oxyrhynchus (‘Sharp-nosed fish’), records that there were two hieroglyph-cutters active in the town.3 One wonders how they kept themselves occupied, but perhaps there was enough work to be had completing or repairing inscriptions in the Egyptian-style temples that still operated, or fulfilling the occasional new commission for a stela or a statue. Carving hieroglyphic inscriptions was a dying art in Roman Egypt, almost a heritage industry. By the late second century AD it was rare to see coherent hieroglyphic inscriptions, although some still appear painted on intentionally old-fashioned-looking coffins and burial shrouds.4 Over the next hundred years or so, knowledge of how to read and write hieroglyphs gradually dwindled to a few ageing specialists, likewise the Demotic and hieratic scripts, which ceased to be employed as Coptic gained acceptance. But interactions between languages and choices of script depended on an individual’s or social group’s priorities, making it impossible to pinpoint when knowledge of a language, or its written form, died out. In early third-century Thebes, for instance, papyrus handbooks of Egyptian prayers, rituals and magical invocations were written down in Demotic but have marginal notes in both Old Coptic and Greek, because the people compiling and using these scrolls were comfortable translating religious formulae across all three language forms.5 Egyptologists can identify the last securely dated hieroglyphic inscription, carved in AD 394, in the temple of Isis at Philae, in the far south of Egypt; the temple also has the latest Demotic inscription, from AD 452. That there was any effort at keeping the old scripts and languages alive shows how important they were to the self-identity of Egyptian culture, and how different languages and religious beliefs coexist.

Sometime in the fifth century an Egyptian priest or scholar named Horapollo saw a need for a study of Egyptian hieroglyphs that would expound the pictorial writing system to audiences literate in Greek. Accounts differ as to who exactly Horapollo was, where he lived (perhaps Alexandria) and whether he is in fact the author of the most famous work ascribed to him, the Hieroglyphica.6 A manuscript of the Hieroglyphica discovered on the Greek island of Andros was acquired by a Florentine nobleman travelling in Greece in the early fifteenth century. He brought it back to Florence, where it caused a stir in humanist circles of the Italian Renaissance, especially after the leading Venetian printer Aldus Manutius published an edition in 1505. A Latin translation followed a few years later, bringing the text into wider circulation. The Hieroglyphica sets out to interpret 189 hieroglyphic signs, which it does chiefly through allegorical readings of what they represent. To Renaissance scholars eager to supplement their knowledge of ancient Egypt, alongside their studies of ancient Greece and Rome, Horapollo’s work was a godsend. Giordano Bruno and Erasmus were just two of many who drew inspiration from it.

Unfortunately, Horapollo had no idea what he was talking about. Or rather, he had an idea, but it bears little relationship to what we now understand about the phonetic and ideographic values of Egyptian hieroglyphs. Instead, the associations he drew between signs and their meanings must reflect ideas that had already developed, presumably among Egyptian specialists themselves, about the metaphorical and magical significance of hieroglyphic writing. Many of the interpretations proposed in the text derive from extrapolations about the object or, especially, animal that a sign represents. For the hieroglyph of a swallow, which was used to write the word wer, ‘great’, Horapollo offers the meaning ‘inheritance from parents to their sons’, because the female swallow (he asserts) rolls herself in mud to build a nest for her young when she herself is about to die. Other interpretations in the Hieroglyphica do capture the essence of the ancient Egyptian sign, even if Horapollo augments or explains it with associations we do not recognize today. The jackal hieroglyph, for instance, he identifies with embalmers, one link it had in ancient Egypt thanks to the jackal-headed god Anubis, who mummified the dead. But Horapollo broadens the meaning of the jackal (or dog) sign to include scribes and the spleen, among other things. Each suggested meaning has an explanation in the animal itself: scribes because, like dogs, they are fierce and protective, and the spleen because in the jackal or dog this organ was considered weak, according to medical principles of the time.

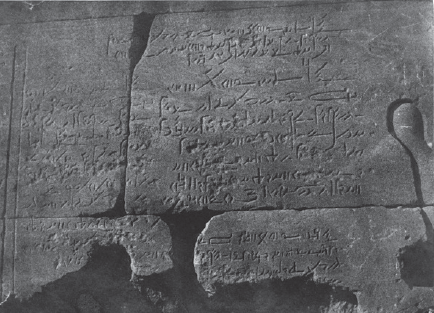

Maxime Du Camp, photograph taken between 1849 and 1851 of a Demotic inscription at the temple of Isis, Philae, dating to the 4th century AD. Salted paper print, 1852.

Even if we dismiss the Hieroglyphica as an accurate or useful guide to hieroglyphs, it both reflects, and helped shape, ideas about emblems and symbolic expression that were current among the intelligentsia of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Europe. It also appeared to confirm what other Greek and Latin texts had to say about the astonishing knowledge and secret wisdom possessed by the Egyptians. Scholars in Europe hoped that Horapollo would help them translate the few inscriptions that were available at that time, especially in Italy where hieroglyphic inscriptions could be found on Egyptian antiquities imported in Roman times – or ancient Roman versions of Egyptian monuments, not that early modern viewers could tell the difference. The narrow selection of signs Horapollo discussed, however, and the circumlocutory way in which he discussed them offered little practical guidance.

In Egypt, Arab scholars faced a similar dilemma. There was ample interest throughout the medieval period in the picture writing of ancient Egyptian culture, given that hieroglyphs covered temples, tombs, and the statues and other objects that were regularly unearthed or reused, up and down the country. Because Coptic and Arabic coexisted for several centuries in Egypt, some scholars in the medieval Arab world had a better understanding of Egyptian scripts than Horapollo and his Renaissance admirers. Ibn Wahshiyah, who lived in the ninth century, was one of the best known of these scholars, whose work was copied and circulated for centuries; he recognized that some hieroglyphs were phonetic, while others represented ideas.7 Arab writers like Ibn Wahshiyah were themselves familiar with Horapollo, and among alchemists and Sufi mystics (the two often went together) the symbolic aspects of hieroglyphic writing held a strong appeal, as did the decorative potential, proportions and symmetry of all the ancient Egyptian scripts. Arabic calligraphy, especially as practised in medieval Sufism, shared similar aesthetic values, while alchemy, which was an important branch of science in the medieval Arab world, appreciated the cryptographic use of hieroglyphic signs, which ancient Egyptian priests had developed into an art form in some temples and papyri. Writing that offered the potential for double meanings and concealment could be translated into something better than words: power.

The Mediterranean connected Christian Europe and the Islamic Middle East, even at times when political divisions or military conflicts, like the Crusades, disrupted diplomatic relations and trade between the different powers. People moved, and where people moved, objects moved – like the manuscript of Horapollo first brought to Florence from Ottoman Greece in the fifteenth century. Because of these exchanges, and the active seeking out of ancient manuscripts for early modern collectors in Europe, the work of Arab scholars was as readily available to learned men as that of Greek and Latin authors, as long as one mastered the necessary languages. One man who did – he knew more than a dozen languages, including Arabic, Coptic, Hebrew and Syriac – was Father Athanasius Kircher (1601/2–1680), a German-born Jesuit priest who spent the latter part of his career teaching and researching in the order’s college in Rome.8 Kircher was a man of letters in the Baroque fashion, a polymath with interests not only in languages, ancient Egypt and China, but in hydraulics, mathematics and volcanology. He enjoyed the patronage of the Habsburg Holy Roman emperors and, in Rome, popes Urban VIII, Innocent X and Alexander VII. Although interest in Kircher’s work has grown in academic circles over the past twenty or thirty years, by the end of his own lifetime younger thinkers were already treating his vast output with some scepticism, and Kircher found no favour with Enlightenment-influenced scholars like Jean-François Champollion, who would decipher Egyptian hieroglyphs in the 1820s.

Kircher flourished at a specific juncture in European science and the history of ideas. The Renaissance rediscovery of ancient Greek and Latin texts, like Horapollo’s Hieroglyphica, went hand in hand with the study of texts in the so-called Oriental languages like Hebrew and Arabic, because the entire Mediterranean and Middle Eastern world appeared to European eyes as part of European heritage. From Athens to Alexandria, from Jerusalem to Babylon in Iraq, from Turkish Anatolia to Palmyra and Persia: in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries these multicultural, multilingual geographic reaches were all considered to have played a role in the formation of Christian culture. As the Protestant Reformation and, in Kircher’s youth, the Catholic Counter-Reformation rocked Europe, understanding this heritage took on new urgency. That is one reason why sixteenth- and seventeenth-century scholars treated the philosophy attributed to Hermes Trismegistus as seriously as the philosophy of Aristotle or Plato, even more so. Ideas that now seem esoteric comfortably coexisted with Christian theology. Parsing hieroglyphic inscriptions for the lost wisdom of the ancient Egyptians presented no problem for a Catholic priest like Kircher, or the popes he served.

When Pope Innocent X, from Rome’s powerful Pamphili family, commissioned a fountain to stand in front of his ancestral palace in the Piazza Navona, he turned to two men for the design: Rome’s leading sculptor, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, and its leading scholar, Kircher.9 The fountain symbolized the supremacy and global reach of the Catholic Church, from the rocky terrain at the bottom referencing its founder, St Peter, to the four famous river sculptures representing Africa (the Nile), Europe (the Danube), Asia (the Ganges) and South America (the Río de la Plata). Rising up from the rivers was a 16.5-metre high, red granite obelisk carved with Egyptian hieroglyphs and topped with the Pamphili family dove. This particular obelisk had been quarried in Aswan, southern Egypt, in the first century AD on behalf of emperor Domitian. It probably stood in front of temples dedicated to the Egyptian goddess Isis and her Hellenistic consort Serapis near the centre of Rome, and its hieroglyphic inscriptions, perhaps composed by Egyptian priests resident in the city, include Domitian’s full name and the title autocrator (emperor), transcribed phonetically. In AD 309 emperor Maxentius moved the obelisk to the new Circus he had built, where it probably toppled over, or was felled, during the unrest of the seventh century. By the time Bernini re-erected it in 1649, it had lain in five pieces for centuries.

Creating the fountain and repairing the obelisk were expensive undertakings in straitened economic times, which did not stop Innocent X raising taxes on Rome’s urban poor to pay for it all.10 Kircher obliged by making a complete study of the obelisk, which he published as an illustrated book in 1650, including his translation (as he saw it) of the Egyptian inscriptions. Confident in his command of hieroglyphs, he also advised Bernini’s workshop on how to fill the gaps in the ancient inscription where the obelisk had been broken, as a result of which the hieroglyphs, already composed in a distinctive, Roman-period style, look especially odd today.

The great Kircher was not infallible: he was once forced to concede that the hieroglyphs on another obelisk he had ‘translated’ were the work of an artist’s imagination.11 It was an embarrassing episode. Influential and well connected as he was, other scholars were sceptical of Kircher’s work during his own lifetime, and his elaborately printed books fell from favour after his death. In retrospect, Kircher seems like a link between the ‘lost’ knowledge of reading hieroglyphs and the triumphant moment in 1822 when Champollion announced his decipherment of the script. But this assumes that knowledge emerges in a linear line of progression, whereby the accurate study of evidence leads us ever closer to some truth. The changing fashion for Kircher’s ideas demonstrates that knowledge does not work that way: what we know, or think we know, is created and recreated at different times, in different circumstances. Moreover, knowledge is never free from the concerns of politics, religion and other influences; witness the way the Arabic sources Kircher used have since been downplayed, distancing the contributions of Middle Eastern scholars. Accuracy and evidence are just as changeable, since opinions have varied over time about what constitutes evidence and how best to identify and interpret it. Today, academics consider the changing valuation of evidence and argument to be essential to the study of knowledge, known as epistemology.

Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Four Rivers Fountain, Piazza Navona, Rome, 1648–51, supporting an obelisk from the reign of emperor Domitian, late 1st century AD.

In eighteenth-century Europe the Enlightenment reacted against previous modes of thought like Kircher’s, divorcing ‘religion’ and ‘science’ and establishing the modes of academic discourse more familiar to us now. A new standard of evidence-based inquiry called for direct study, the use of measuring and recording devices, and, increasingly, the professionalization of scholarship in institutes, museums and universities. Hence the rationale for Napoleon’s scientific expedition, in which savants and soldiers alike hunted for ancient manuscripts and monuments alongside their mapmaking, mineral-sourcing and military strategizing. Had Athanasius Kircher known about the Rosetta Stone, would he have parsed the Demotic and hieroglyphs in relation to the Greek text, or would he have dealt with it in much the same way as he had the Piazza Navona obelisk, interpreting them as metaphorical expressions independent of legible and logical Greek? Some 150 years later, perhaps it was not so much that Champollion was the right man for the Rosetta Stone, but that the Stone had appeared at the right time.

How the Rosetta Stone came to be in the British Museum is written directly on it, in a fourth language that few viewers seem to notice: English. On the hewn sides of the Stone, white-painted lettering reads, on one side, ‘Captured in Egypt by the British Army in 1801’, and on the other, ‘Presented by King George III’. The massive stone – it measures 112 cm long, 76 cm wide and 28 cm thick – was uncovered by the French army during operations at Fort St Julien at Rosetta (el-Rashid) in the Delta in July 1799. The lieutenant in charge, Pierre-François Bouchard, recognized its potential importance and brought it to the attention of division commander General Jacques-François Menou, who was governor of the province under the French occupation – and who, coincidentally, later converted to Islam, took the name Abdullah and married an Egyptian woman. Menou ensured that the discovery of the Stone, with its three distinct scripts, was announced to the Institut d’Égypte, which Napoleon had established in Cairo as the home of the savants. Copies were made by inking the stone and using it as a printing plate, with the results sent back to France in hopes that scholars there could make some headway with the hieroglyphic script at the top.12

In 1800 Menou became head of the French army in Egypt following the assassination of Napoleon’s right-hand man, General Kléber, who had been trying to reach a truce with the British. Instead, it fell to Menou to try to shore up French military efforts in Egypt. After a prolonged siege at Alexandria, Menou surrendered to the British in 1801. In negotiating the terms of the surrender, Menou preserved the scientific expedition’s notes, maps and drawings, arguing that they were private property and thus not subject to martial laws. He tried the same argument to keep possession of a number of antiquities, but British officers insisted on treating moveable monuments as state (that is, French) property unless they could clearly be shown to be personal goods. Menou tried to keep the Rosetta Stone concealed among his own belongings, but British officers spotted it, deemed it unlikely to be merely for Menou’s own use, and shipped the Stone to London in 1802 on the appropriately named captured French frigate, HMS Egyptienne. The Society of Antiquaries displayed the Stone at their rooms in Somerset House and had plaster casts of it made for the leading British universities of the day, as well as further print copies. Together with other monuments and statues seized from the French, the Rosetta Stone went on display in the British Museum in the summer of 1802.13

Visitors to the museum commented, often unfavourably, on the contrast between the dark colours and stiff contours of the Egyptian objects and the flowing white marble of the Classical sculptures displayed nearby. However, the chief interest in the Rosetta Stone was not what it looked like, but what it said. Its specialist terminology meant that even reading the Greek inscription took some effort. The French scholar Silvestre de Sacy (whom we met earlier in this chapter) recognized the middle script as Demotic, and in collaboration with the Swedish diplomat and linguist Johan Åkerblad managed to identify a few Greek names among the Demotic signs. It was de Sacy who remarked, in a letter to the British scientist Thomas Young, that comparing the royal names in Greek and Demotic to the cartouche-encircled signs in the hieroglyphic script might be a fruitful approach – and so it proved, for Young was able to work out the alphabetic spellings of names like Ptolemy, publishing his results in 1819.

In the meantime, Young also corresponded with de Sacy’s younger rival in France, Jean-François Champollion. Champollion consulted not only prints of the Rosetta Stone, but copies of other inscriptions circulating at the time, in particular a bilingual Greek and Egyptian obelisk owned by explorer William John Bankes (who first recorded it at the temple of Isis on Philae in 1815, and in the 1820s had it transported to Kingston Lacy, his country home in Dorset). Helped by his knowledge of Coptic and the dual Greek–Egyptian inscriptions, Champollion finally produced a near-complete sign list of Egyptian hieroglyphs with their phonetic values, published in a letter to the French Academy in September 1822. He also recognized that hieroglyphic words included signs that were not pronounced, and it was this combination of insights that enabled him to translate hieroglyphic texts in a meaningful way. Champollion became a leading figure in the new field of Egyptology, although his early death at age 42, just ten years after he announced the decipherment, meant that he taught few students and published only a fraction of his work.

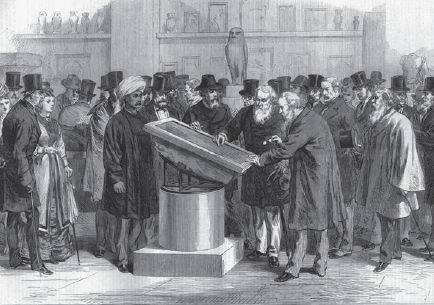

Scholars attending the International Congress of Orientalists examine the Rosetta Stone in the British Museum, 1874.

The ability to translate ancient Egyptian texts revealed how weird and wonderful they can be – and how normal, too. Anyone still expecting Hermes Trismegistus’ guide to the mysteries of the universe was bound to be disappointed, as was anyone expecting the act of translation to be straightforward. The Rosetta Stone proved to be a case in point, with each of the three scripts conveying a similar, but not identical, version of a decree issued in 196 BC by the young king Ptolemy V. The Demotic text, which is the most complete, begins with a long list of the king’s Egyptian names and expressions for the date, before recounting everything he had done to benefit Egyptian priests and their temples, including reductions in taxes and giving up his claims to certain temple revenues. In return, the priests agreed to install a statue of Ptolemy,

together with a statue for the local god, giving him a scimitar of victory, in each temple, in the public part of the temple, they being made in the manner of Egyptian work; and the priests should pay service to the statues in each temple three times a day, and they should lay down sacred objects before them and do for them the rest of the things that it is normal to do, in accordance with what is done for the other gods on the festivals, the processions, and the named days.14

If this was done in every major temple, it represented a significant undertaking, especially since versions of the same decree, since discovered on other stela fragments, confirm that it applied throughout Egypt. Scholars today surmise that the capitulations indicate how much Ptolemy V needed the support of the indigenous priesthood at a time of civil strife.

With breaks at the top, bottom and sides, the Rosetta Stone is clearly a fragment of a larger monument – but what kind? Until 1999 the British Museum displayed the Rosetta Stone lying on its back at an angle, as if it were a book resting on a giant stand. This presentation of the Stone was in keeping with the way it had been treated ever since French troops identified it: as a text to be read in the way that contemporary readers hold books or papers. Applying ink to the surface to print copies emphasized its pagelike character. The British Museum also applied a layer of wax to the Stone in the early nineteenth century, to try to protect it from the dirt and oil of human hands; the Stone was displayed uncovered, and visitors were eager to touch the famous object. By 1981 the surface of the Stone was so dark that the Museum added white paint to the incised writing in order to make the inscriptions stand out.

Conservation work undertaken for a special exhibition in 1999 was able to remove the accumulated layers and reveal the Stone’s original appearance: a mottled grey granodiorite, with a streak of pink stone running through its broken upper edge. In addition, the Museum decided to display the Rosetta Stone in its original intended position, since it had been designed in antiquity to stand upright as a free-standing stela. Reconstructions based on similar monuments suggest that the Stone extended another 50 cm or so to a rounded top, which would have been carved with Egyptian-style images of Ptolemy before the gods of the temple in which the Stone stood. Although probably set up in a semi-public space, like a temple forecourt, the Stone was not intended as a text that people would stop to read. Even if they knew how to read any of the scripts, the terminology is so specialist, and the text inscribed so small and low down, that reading and understanding it would be a challenge. Instead, like the first hieroglyphs used in the earliest days of the Egyptian kings, the Rosetta Stone used writing to display knowledge and privilege. The Rosetta Stone was never an open book, whether on plain view in a temple or in a museum. In the wake of Champollion’s decipherment, European scholars thought they had finally unlocked the secrets of ancient Egypt, but at the risk of forgetting why secrets were written down in the first place.

An artist’s reconstruction of what the Rosetta Stone looked like in antiquity.