FIVE

WALKING LIKE AN EGYPTIAN

|

FIVE |

In his classic book Art and Illusion, first published in 1960 and never out of print, the eminent art historian Ernst Gombrich used a New Yorker cartoon from 1955 to open his discussion of how different artistic styles over time have tried to represent the world just as it looks in human vision.1 In the cartoon a group of young men, all bald-headed and wearing pleated skirts, are in a life-drawing class preparing to draw the model on the platform in front of them: a slender woman depicted by cartoonist Alain in recognizable Egyptian form, with her legs, arm and face in profile. To Gombrich, the cartoon captured a fundamental difference between Egyptian art and artists and the artists of the Greek tradition that Renaissance Europe inherited. Western artists tried to draw what they observed with their own eyes, while Egyptian artists drew what they had been trained to draw, a schema for representing ‘the world’ in a way that bore little resemblance to visual perception. The humour of the New Yorker cartoon is that we know Egyptian women did not look like the stiffly twisted, striding model, and that Egyptian artists did not train from life-drawing, squinting down their arms at their pencils to gauge proportions and perspective. The joke is on us, for ever assuming that ‘our’ way of making pictures is the only way, or that it was possible – in the words of The Bangles’ pop song – to walk like an Egyptian.

Art historians of Gombrich’s generation, however, did give priority to the lifelike, illusionistic representation favoured by ancient Greek and Roman art and by Renaissance and later European artists. The idea that the more closely a work of art resembles what it represents, the better the artwork is (and the more talented the artist, too) is an idea that has a powerful, pervasive hold on our collective imagination. We all know someone who dislikes Cubism, Abstract Expressionism or just about any contemporary art because such art is not figurative, that is, it does not depict human or animal figures, landscapes or anything else from the natural world in a ‘natural’ way. But what is ‘natural’ for art changes across times and cultures. When their work debuted in nineteenth-century France, the Impressionist painters were decried for their failure to represent the world accurately. All those fuzzy outlines and pastel hues, easily read today as scenic views and water lily ponds, were a radical departure at the time. How much more alien, then, the art of ancient Egypt seemed to be, together with the art of many other ancient cultures – Babylonia, Assyria, pre-Classical Greece, India and all the pre-Columbian societies of Meso-and South America.

Flip the history of art around, though, and the trickery of naturalistic or lifelike art turns Classical Greece and its imitators into the odd ones out. To represent the world as our eyes perceive it, painters and mosaic artists had to foreshorten parts of the image meant to be closer to the viewer, shade some surfaces to convey volume, and make figures or buildings in the distance smaller in relation to the foreground; you can see this in the Herculaneum fresco of Egyptian priests and the Palestrina mosaic of the Nile. In sculpture, the contrapposto posture, in which subjects shifted their weight onto one leg, creating a sense of motion through the body, made statues look almost like living bodies trapped in molten metal or turned to stone. These choices reflect specific historical circumstances and cultural values in, for instance, fifth-century BC Athens or early imperial Rome. The conventions that Egyptian artists used were also a conscious choice, made early in Egyptian history and carefully preserved and transmitted for millennia. In the same way that we recognize art that looks Egyptian, so, it seems, did ancient audiences. When Egypt was an influential power and an exporter of desirable goods, artists elsewhere copied Egyptian styles, and when Egypt became a Greek kingdom and then part of the Roman Empire, artists combined Egyptian forms of representation and architecture with the naturalistic forms that then held sway. It is not only Gombrich, or cartoonist Alain, who could spot the difference between two competing systems for turning the world around us, and within us, into a picture.

Nevertheless, an artist in the time of Cleopatra would not ‘get’ the New Yorker cartoon, because its absurdities are distinctly modern: the male artists and the female model, the institution of life-drawing classes, and the telling details – palm trees, chair shapes, kilts – that Alain used to indicate the setting as ancient Egypt. In this chapter we begin by considering what made Egyptian art look Egyptian to ancient eyes, and why it stuck with certain conventions in architecture, two-dimensional paintings and reliefs, and three-dimensional sculpture. Turning to European ideas about ancient Egyptian art, we pick up with the impact of the Napoleonic expedition and the early nineteenth-century opening of Egypt to Western visitors. How artists and designers used Egyptian-inspired decoration, architectural elements and subjects reveals how firmly ancient Egypt was fixed in the Western imagination as a sign of the mysterious, the mighty and the exotic Other, even when its art was admired for a certain delicacy or beauty. Nowhere is this tension between East and West, strangeness and beauty, stilted and lifelike, more apparent than in representations of Cleopatra herself, the queen whose shared Greek and Egyptian identities exemplify the quandary of what it has meant in the modern world to have ‘lost’ this ancient past.

The female model in the New Yorker cartoon looks similar to the bronze plaque of the Nile-god Hapi, which we saw in the previous chapter, or the figure of lady Tabakenkhonsu, painted on her funerary stela (see p. 12). The figures face left, with the face in profile, the shoulders almost squared to the viewer, and the arms and legs also in profile, one foot in front of the other. Look more closely, and it is clear that several areas of the body – the stomach and belly button, the line of the back and buttock, those impossible shoulders and single-breasted chest – do not correspond to how a real body would appear in real space. Instead, they are indications of the body: lines and curves that link the head, torso and limbs together in a coherent whole that reads ‘male’ or ‘female’, ‘human’ or ‘divine’. Like hieroglyphs, these figures could also be flipped around to face right. In fact, right-facing was the ideal orientation for Egyptian images, as it was for written texts; the three-line prayer on the bottom of Tabakenkhonsu’s stela reads from right to left, for instance. But to make it possible for images and texts to be arranged on left and right walls in a room, or the left and right sides of a statue, reversibility was essential.

If the bronze Hapi, lady Tabakenkhonsu or the god Thoth, who holds her hand, were flipped to face right, the forward leg would be each figure’s left leg, the one farthest from the viewer – like the feet of the goddess Nut as she fills the ‘sky’ of the painted wooden stela. In the scene of Tabakenkhonsu with Thoth, Isis and Osiris, short texts identifying each figure face in the same direction as that figure. From around the time the first pyramids were built, statues in Egypt always represent kings and high-ranking men standing with the left leg forward, probably inspired by the preferred orientation of hieroglyphs and other two-dimensional images, which had already been established. Egyptologists often refer to this pose for statues as the striding stance, because the advanced leg suggests that the figure is walking or about to step forward. Statues of women represent them with their feet together until the New Kingdom, when sculptors began to show some high-status women with the left foot advanced. By the Ptolemaic period, statues carved in traditional Egyptian style, often from dark Egyptian stones, used a confident striding stance to depict powerful queens such as Arsinoe II, Cleopatra III and Cleopatra VII (the famous one). One such statue, now in a museum belonging to the Rosicrucian Order in San Jose, California, dates to the first century BC and may represent either Cleopatra III or VII; without an inscription, it is impossible to say for certain.2 Probably set up in an Egyptian temple, this granodiorite statue relied on stoneworking techniques that Egyptian masons had perfected over centuries. It represents the queen in a style that was intentionally old-fashioned, as a way to associate her with a long lineage of rulers from the distant Egyptian past. Not only is her left leg far forward, more like a king than a queen, but her arms hang at her sides; queens usually had their left arm bent across the body. The tight curls of hair arranged in three stiff sections – one either side of the face, another down the back – echo the tripartite headdresses depicted on gods and goddesses, and the three cobras on the queen’s forehead triple the conventional uraeus-symbol used for royalty; this was a new feature in the Ptolemaic period. The rounded belly, full breasts, and prominent nipples and navel may make it seem at first glance as if the queen is naked, but the hem of a dress stretches between her lower legs. A youthful, fertile, female body was a sign of beauty and perfection, although today it may seem a sharp contrast to the dour facial features, which are similar to portraits of Ptolemaic queens on their coinage and in marble statues made for them in the Greek style.

Dark stone statue of a queen, probably Cleopatra VII, c. 40 BC.

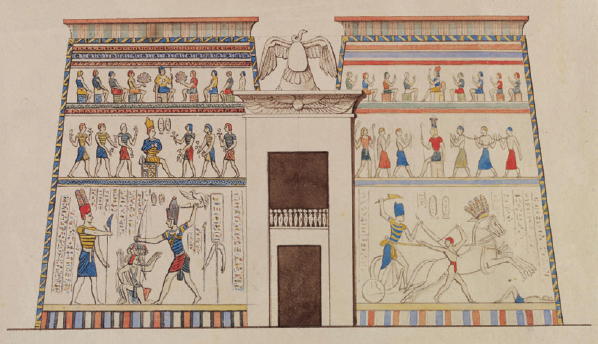

Egyptian architecture also had a distinctive style. Most buildings in ancient Egypt were mud-brick or mud-plastered reeds, not unlike the wattle-and-daub technique used in medieval Europe. But tremendous effort went into monumental stone architecture for tombs and temples, which is what survives to such an impressive extent today. From the New Kingdom onwards, temples were fronted by monumental gateways, often known by the Greek word pylon. The pylon controlled actual and symbolic access to the temple’s forecourt and inner rooms, which were off-limits to anyone but priests and attendants in a state of ritual purity. A drawing by the Victorian designer Owen Jones depicts the facade of a temple pylon, although the scenes and inscriptions painted on it are only approximations, not direct copies. What Jones has right, though, is the sloping shape of the pylon walls, their flared top, known as a cavetto cornice, and the lashed detail all around their edges. The cavetto and lashings are echoes in stone of the floppy reed heads and bound reed stems used in simple mud-and-reed structures. Having this echo of the natural world – life-giving Nile-soaked earth and reeds – was important to Egyptian religious ideas about the temple representing the creation of the world and providing a home for the gods. Inside, temples had courtyards and roofed-over rooms supported by columns in the form of papyrus stems, another reference to the river.

The Jones drawing also correctly captures how colourful Egyptian art was. The walls and ceilings of temples were painted in rich colours, and even gilded in parts. Tombs and most statues were also painted, and to nineteenth-century viewers this colourful appearance was an intriguing contrast to the white marble statues and buildings of Greece and Rome (although we now know that those were once painted, too). When Owen Jones designed the Crystal Palace Exhibition in Hyde Park, London, in 1851, the vivid reds, blues and greens of the Egyptian court, which he co-created with Joseph Bonomi, formed a stark contrast to the cool white plaster casts in the Greek court beyond.3 Both men had visited Egypt and both were artists, whose numerous sketches and watercolours of the ancient sites helped them lavish particular care on the Egyptian display in the Crystal Palace, which tens of millions of visitors, including Queen Victoria, saw both in Hyde Park and when the whole structure was re-erected at Sydenham, south London, in 1854. This was ancient Egypt tailored to Victorian taste, and any Egyptologist would quibble with the details. But Jones and Bonomi were not after accuracy so much as effect, and the symmetry, rhythmic repetition and direction of the mock-temple conform to the spirit, if not the letter, of ancient artistic practice. The dominant figures – gods and goddesses – face towards the doorway, and a fecundity figure appears in the bottom band of one wall, which is exactly where such figures belonged in an Egyptian decorative scheme. The walls of tombs and temples, or drawings made on papyri, were always divided into horizontal bands, termed registers. From the top to the bottom of a wall (not visible in the photograph above), each register enforced a subtle hierarchy, and in a genuine tomb or temple chamber what belonged in each register and on each wall or doorframe had to fit together into a coherent whole. Rather than the life-drawing lampooned by cartoonist Alain, an Egyptian artist’s training included structuring a programme of decoration, fitting figures and inscriptions together, and learning proportions, patterns and insignia by heart. In ancient Egypt, art was too powerful to leave to creative whim. If Egyptian art and architecture looked stilted or gaudy to some nineteenth-century viewers, others found it delightful, unusual or even alluring enough to put it to new use.

Owen Jones, watercolour showing the entrance pylon of an Egyptian temple, 1833–4.

Philip Henry Delamotte, photograph of the Egyptian Court at the Crystal Palace exhibition, Sydenham, London, 1850s–60s.

In the years after the Napoleonic expedition to Egypt, and especially after Vivant Denon published a popular account of his own involvement, a vogue for Egyptian-inspired interior design caused a small stir in Britain and continental Europe, especially France.4 Always a niche taste – Egyptian-style furniture and tableware did not fit easily into the average home – this ‘Egyptomania’ confirmed that ancient Egypt appealed to European interests, but only at a certain remove. English designers like Thomas Hope offered drawing-room chairs with sphinx-shaped arms, and Josiah Wedgwood made a red-and-black tea service encircled with winged scarabs; a crocodile formed the teapot lid. Cupboards and clocks also had the Egyptian treatment. Chairs and teapots may have been novelty items, but cupboards and clocks perhaps suited an Egyptian theme: closed cupboards evoked secrets and security, while timepieces matched Egypt’s deep antiquity and concern with endurance. A marble and gilt bronze clock by the London firm of Vulliamy & Son borrowed designs directly from Denon’s account of his travels in Egypt. Four sphinxes support the clock face, which is mounted on a cavetto-cornice ‘gateway’ with battered sides and a winged sun-disc at the top.

By the late nineteenth century the development of tourism and archaeology in Egypt – both linked, as we have seen, to colonial and imperial interests in the country – meant that ever more accurate renderings of ancient monuments were available for consumption around the world, especially with the rise of photographic technology. Museums also filled their display cases with growing numbers of finds from archaeological excavations, since foreign excavators at the time were allowed to keep much of what they discovered. Whether through books, in museums or on their own travels, a widening audience could form ideas about ancient Egypt thanks in part to the more commonplace objects – baskets, vases, tools and jewellery – that archaeologists now saved, rather than the architectural fragments, statues and coffins that interested earlier collectors. Designers were attracted by the handmade elegance of Egyptian furniture. For instance, the Pre-Raphaelite painter William Holman Hunt designed ebony-and ivory-inlaid chairs closely inspired by ancient examples he had seen in the British Museum, down to the curve of the cane seat.5 Holman Hunt had travelled to Palestine to help him paint works with a Christian theme, and he was friendly with members of the Arts and Crafts movement, which elevated handmade over factory-made goods. Here, then, was a gentler version of ancient Egypt than the overpowering architecture copied for cemeteries and Freemasons’ halls (even a prison, in 1840s Philadelphia), or the over-the-top sculptures in the Crystal Palace.

The ‘mania’ in ‘Egyptomania’ implies that popular interest in Egyptian motifs for interior design, fashion or architecture was an uncontrollable, unpredictable urge. In contrast, no one characterized ornamentation inspired by the classical world as a craze – Wedgwood’s cameo-effect china, Greek columns and architraves, replica Apollos and Venuses, all seemed entirely fitting in a domestic interior, country estate or cityscape. But the rediscovery and re-interpretation of ancient Greece and Rome had its own history and social significance, just as the different uses of ancient Egyptian art and architecture did. The crucial points at which Egyptian decor became a fad corresponded to historic events and the availability of sources, such as the Napoleonic expedition and Denon’s book in the early 1800s, the Crystal Palace Exhibition and new Egyptian galleries at the British Museum in the 1850s, or the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869. Flushed with the success (and income) of the Canal project, khedive Ismail commissioned Giuseppe Verdi to compose the opera Aida, which inaugurated the Cairo opera house in 1871 – and may have helped inspire a fresh burst of Egyptian inspiration in Verdi’s native Italy. Some producers and consumers of Egyptian-themed design had an interest in biblical history, or in Freemasonry, but whatever specific appeal the arts of ancient Egypt held, their general association with the marvellous and mysterious held sway. No matter how familiar it became, ancient Egypt kept a touch of the alien and other, which only a ‘mania’ could explain.

Vulliamy & Son, mantle clock in Egyptian style, made in London, 1807–8.

Cast metal door guard in Egyptian style, on an apartment building in Bologna, late 19th century.

In the 1920s the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun launched another period of Egyptian fashion in home interiors, clothing and popular entertainment – ‘Tut-mania’, this time. In Britain, where the press covered the English-led excavation in detail, Huntley and Palmer biscuit manufacturers issued a biscuit tin in ancient Egyptian style, and a Lancashire textile firm printed furnishing fabrics with Egyptian motifs. The Times of London and other newspapers seized on the chairs and candle-holders, baskets and walking sticks, clothing and perfume pots in Tutankhamun’s tomb to paint a picture of cosy domesticity for the boy-king, which the modern middle classes could recreate at home. This tame, Tut-friendly view of antiquity made for a convenient contrast with the post-First World War turmoil of the Middle East, where Egypt was struggling to free itself from British political and military domination. Egyptians seeking independence had clashed with the British army in 1919, and when free elections were finally held in Egypt in 1922, just months before the Tutankhamun discovery, the first prime minister was nationalist leader Sa’ad Zaghloul, whom Britain had twice sent into exile. Excavator Howard Carter, who had spent his entire working life in Egypt, misjudged the new mood when it came to the Tutankhamun discovery, granting exclusive access to the London Times and expecting to share objects from the tomb with his backers in England and New York. The Egyptian government, which included French and British employees, revoked his excavation permit for a year, exerting their own rights over the tomb and its reawakened pharaoh.6

Delicate prints, faux scarabs and glitzy biscuit or cigarette tins gave ancient Egypt the common touch, from Paris to Peoria, but as we will explore in later chapters, modern Egyptians and members of the African diaspora were beginning a long battle for greater recognition and social change. The singular features of ancient Egyptian designs could be adapted to many different uses and purposes, some frivolous, others with more serious intent. Nor were Egyptian-style architecture and decorative arts the only sphere in which this ancient culture’s visual legacy was reshaped amid contemporary concerns. Since at least the early nineteenth century, fine artists (and later, photographers) had been representing the antiquities of Egypt as romantic, empty spaces ripe for colonial expansion, or as stage sets for exotic, and often erotic, glimpses of the past. Some of the most renowned painters of their day conjured up an ancient Egypt peopled by characters who were just like us, but not quite. This imagined Orient was a place of contradictions: old and new at the same time, familiar yet unfamiliar, too. Because many artists anchored their versions of ancient Egypt in surviving evidence, as Holman Hunt had done with his Egyptian chairs, their creative licence easily seems more real than the real thing, but it would be our mistake to confuse the two.

The Dutch-born painter Lawrence Alma-Tadema kept a wooden couch in his London studio to use as a prop in his paintings. Now in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the couch had one long side and its pair of legs carved in Etruscan style, and the other side and its legs in Egyptian.7 It served Alma-Tadema well in his lush, finely detailed oil paintings of ancient life, which earned him fame and fortune in Victorian Britain. Although scenes of Greece and Rome were his most popular subjects, Alma-Tadema painted several well-received scenes from Egypt and the Bible as well, such as the discovery of the infant Moses in the Nile. In addition to studio props like the couch, Alma-Tadema closely researched antiquities and ancient architectural features through books and museum visits. Recognizable details, combined with the expressive characters he painted, brought the ancient past to gleaming life under Alma-Tadema’s brush. Or did it? The footstools and ostrich-feather fans looked authentic enough – but the blushing, pale-skinned women of his paintings, the occasional dark-skinned man for contrast, and the fresh, flower-filled spaces these figures occupied could only be a fantasy, a drawing-room version that filtered fragments of antiquity through Victorian taste.

Representing fictional or historical characters from ancient Egypt in the realistic style of Western art had an immediate visual impact in that it did away with the conventions of Egyptian art, whose human figures looked so stiff and regimented to modern viewers. Where the originals seemed remote and alien, the reconstructions that history-minded painters created managed to transport viewers back in time. Alma-Tadema’s 1872 painting The Egyptian Widow combines his closely observed execution of Egyptian art and architecture with an imaginary scene of mourning, as the widow of the painting’s title kneels weeping next to the mummy of her husband. In the background, five male musicians sit cross-legged on the floor, singing, shaking the tambourine-like sistrum or strumming a harp. The setting is an Egyptian temple with elaborate papyrus-shaped columns and low walls that give a view onto a palm-filled courtyard beyond. Alma-Tadema was a master of detail: the cavetto-cornices, lashed edgings and rows of rearing cobras are close renderings of actual architectural features, as are the richly coloured column capitals. A basket on the floor, the wooden door panel, musical instruments and the altar-like arrangement of jars to the right (so-called canopic jars, used to hold mummified organs) are all based on objects Alma-Tadema could see in museums, especially the British Museum in London, where he had lived since 1870. It was in the museum’s upstairs galleries, colloquially known as ‘the mummy rooms’, that he would have seen the coffin to the left of the widow, and the shrouded mummy shown lying on a wooden bier with the legs and tail of a lion. Both the coffin and the mummy date to the era of Roman rule in Egypt but use images of the gods in a purposely old-fashioned way. Alma-Tadema was not as interested in historical accuracy as these closely observed studies might suggest, however. He has combined a coffin and mummy from the second century AD with canopic jars from a thousand years earlier, and covered the temple walls with scenes from tombs a few hundred years earlier still. For Alma-Tadema and his audience, the interest lay instead in the overall effect of a ‘real’ ancient Egypt to support the emotive heart of the painting: a mourning widow, her face buried in her hands and her hair falling forward (like the mourners in Egyptian art), while the familiar bald-headed priests perform a funeral dirge. Our heart strings are being plucked as surely as the harp.

Lawrence Alma-Tadema, The Egyptian Widow, 1872, oil painting.

On the one hand, erasing the gap of time and space between an Egyptian temple and a Victorian art gallery encouraged empathy or identification with people from the ancient past, which we tend to take for granted as a positive effect. On the other hand, not only time and space were erased in this process: centuries of Egyptian history were erased as well, especially from the seventh-century introduction of Islam to the present day. Paintings with ancient Egyptian themes were part of a wider set of cultural signals that reinforced an artificial split between East and West, with ancient Egypt reserved for the enjoyment of white, Christian Europeans. And race did matter: the pale or tawny skin of the widow and four of the magicians makes an intentional contrast with the dark skin of the harpist. In the nineteenth century viewers were closely attuned to even subtle distinctions in gradations of skin tone and what they implied, in the dominant ‘science’ of the day, about racial identity, admixture and human progress.8 Africa, the dark continent of the colonial imagination, seeped around the edges of ancient Egypt, a silent shadowing. To keep Egypt within the circuit of what was considered Western heritage, this Africa had to be kept in its place, wedged into a corner like the black harp player.

Such anxieties about race, belonging and the ownership of the Egyptian past were not spoken of directly. Instead, we glean them from what academics call discourse: the shared assumptions through which a society operates, which are created and communicated through visual experiences, writing, performance, commerce, science, political debate and so forth. These elements operate together, not separately. Thus painting ancient Egypt convincingly as a living past relied on the archaeological recovery of Egyptian antiquities, but it also made archaeology seem more important, even urgent, to conduct. At the same time, archaeology in Egypt expanded as Britain tightened its hold on the country following the 1882 invasion and establishment of a ‘veiled protectorate’. In the 1890s several of Alma-Tadema’s fellow history painters, including Edwin Long and Edward Poynter, joined forces with British archaeologists, military officers and politicians to campaign for the preservation and protection of ancient monuments in Egypt.9 The threat they perceived came from two areas: the alleged neglect of antiquities by the Egyptian government that remained in place, since Egypt was part of the Ottoman Empire, and secondly its antiquities service, headed by French Egyptologists. There was also widespread concern about the new dam that the British planned to build at Aswan, which would permanently flood famous temples like the temple of Isis at Philae. In the eyes of the British campaigners, neither the French nor the Egyptians could be counted on to look after ancient Egyptian sites. Imagine the French and the Egyptians complaining about how Britain took care of Stonehenge, and the insult this implied, not to mention the diplomatic wrangling involved, becomes clear. Yet arrogant attitudes set a tone for debates around heritage in Egypt and the Middle East that still echo today. Who decides what counts as heritage, and how best to preserve it?

Heritage is a word that carries considerable weight. It derives from the same Latin root that gives us ‘inheritance’, and until the twentieth century ‘heritage’ referred to property or responsibilities passed down through a family line, especially in legal terms. The idea of heritage as a significant aspect of culture shared by an entire group of people grew out of late twentieth-century moves to protect certain places, landscapes and artworks from development, war or natural disasters. Established in 1945, in the wake of the Second World War, UNESCO is perhaps the best-known arbiter and advocate of heritage today. UNESCO introduced a World Heritage List in 1978, which now includes more than a thousand buildings and monuments, conservation areas and examples of ‘intangible’ heritage, such as dance forms and craft skills.10 The phrase ‘world heritage’ suggests that the preservation of anything designated as heritage is in everyone’s interest, on the assumption that heritage has a universal value. But the fact that world heritage is managed by a United Nations organization, with official entrants nominated by member nations, reveals how closely our modern notion of ‘heritage’ is associated with the nation-building of the nineteenth, twentieth and (consider South Sudan) twenty-first centuries – and thus how closely what is ‘heritage’ depends on the interests of who is in charge, or wants to be.11 Preserving an example of heritage, or destroying it, can both be effective ways for a regime, or its opposition, to legitimize its cause.

If heritage means that culture can be inherited, rather like a royal throne or the shape of a nose, then it can also be fiercely fought over, like any inheritance. Competing cultural memories of ancient Egypt are today often framed as heritage debates, thanks to the dominance of the heritage idea – or indeed, ideal. Yet the movement of people, objects and ideas over the centuries makes it difficult to pinpoint whose heritage anything derived from ancient Egypt is. According to the nation-state model, since the culture of ancient Egypt originated in what is now the country of Egypt, modern Egypt and it inhabitants have a priority claim. Yet museums in London and Berlin reject the idea that ‘star’ objects in their museums – the Rosetta Stone and the bust of Nefertiti – should return to Egypt, and if the Egyptian government decided to raze the pyramids to the ground, there would be an international outcry. Where people take heritage to be less about a nation state and more about kinship and lineage, more quandaries emerge. Are modern Egyptians overly removed from their ancient ancestors by virtue of being predominantly Muslim? This is the argument many people of European descent have made since the eighteenth century, informing the discourse of Orientalism. Ancient Egypt was an early home of Christianity and Judaism, not to mention a major centre of Greek learning and philosophy; hence Europeans considered it ‘Western’ by right. Expanding the idea of the ancient population to include more of the African continent opens still another line of argument. To see ancient Egypt as fundamentally African – many Greek writers referred to it as Ethiopia, after all – allowed people elsewhere in Africa or of African descent to identify the history and culture of Egyptian antiquity as their heritage, too.

Debates concerning heritage often crystallize around high-profile objects (the Rosetta Stone), monuments (the pyramids) or figures – like the famous Cleopatra, a queen who knew a thing or two herself about the inheritance of a throne and the shape of a nose. The French scientist and philosopher Blaise Pascal remarked that had her nose been shorter – in seventeenth-century thought, a sign of weak character – the face of the world would have been different. And indeed, the political confrontation between Cleopatra and Rome changed the course of history, bringing all of North Africa and the eastern Mediterranean under Roman sway. Cleopatra has fascinated artists and writers for centuries because, like ancient Egypt itself, she seemed to be two things at once.

At the time of her defeat, Roman poets called her a whore and a monster, vilifying her as a woman whose feminine wiles led Antony astray and her country into ruin. Like Helen of Troy, a mythical figure, Cleopatra represented the danger a beautiful woman posed to male-dominated order, while the luxury and learning of her Hellenistic court was met with envy and suspicion in the Roman republic. Much of what we know about Cleopatra was written many years after her death, for instance in the lives (moralizing biographies) of Julius Caesar and Mark Antony composed by the Greek writer Plutarch around AD 100.12 Rediscovered and translated during the Renaissance, Plutarch and other Greek and Latin authors were the only sources Europeans had for the life or looks of the queen for many years. Marble portraits of her in the classical style were only identified as such in the twentieth century, based on comparison to her coin portraits. In the late 1990s some scholars identified the dark stone statue in the Rosicrucian Museum as a statue of Cleopatra, too, although the lack of inscription makes it impossible to know for certain. What is important is that there would have been many statues of Cleopatra VII in Egyptian as well as classical style, in her home country, none of which necessarily show us what she looked like in real life. She also appeared in Egyptian form on temples she supported, on her own behalf and that of her son (by Julius Caesar) and co-ruler, Ptolemy XV Caesarion. Egyptian sources and cultural memories in Egypt itself preserved strikingly different ideas about Cleopatra than the Roman and later Western notion of her as a scheming sexpot: Arab historians remember the queen for her wisdom, great learning and achievements on behalf of her country.13

William Wetmore Story, Cleopatra, marble sculpture, modelled 1858, carved 1860.

When the American sculptor William Wetmore Story chose Cleopatra as a subject in the 1850s, he did so without knowing any of these ancient images, only the posthumous Greek and Latin accounts.14 In his studio in Rome, Story specialized in Neoclassical sculpture, and his Cleopatra is one of several near-life-size statues he designed representing legendary or historical women in contemplative moments. Like other sculptors of his day, Story created a clay or plaster model for stonemasons to carve in fine Italian marble, hence several similar versions of the Cleopatra exist, made over several years. When the sculpture was first exhibited, viewers admired its authentic Egyptian detail: the striped cloth headcovering the queen wears is Story’s version of the pharaonic nemes, with a cobra (uraeus) over the brow, and on each wrist the queen has an Egyptian-inspired bracelet with scarabs and snakes. The deep folds of the dress and the way it slips off the queen’s shoulder, revealing one breast, may bring a hint of enticing Orientalism to the statue, but the bare breast also alludes to Cleopatra’s suicide, since convention had it that she held a poisonous snake to her chest to receive the fatal bite. Particularly striking to Story’s American audience in the 1850s and 1860s, however, were the queen’s strongly modelled facial features, with a large, straight nose, cleft chin and firm, full lips. Contemporary viewers took these features as signs of Cleopatra’s ‘Ethiopian’, that is African, identity. Story belonged to a prominent Boston family who were active in the abolitionist movement. His anti-slavery sympathies, and those of his audience in the northern United States, stressed the grave decision faced by Cleopatra and, by extension, the American nation as it weighed its options in the years leading up to the American Civil War. Cleopatra as an African queen, faced with a desperate choice, was a work of art that predominantly white audiences could interpret as ennobling slaves of African descent, whose future, and America’s, hung in the balance.

Few viewers of Story’s Cleopatra today would read its facial features and white marble as African, Ethiopian or black. Art endures, societies change. Viewers are more likely to take the marble queen in her Egyptian headdress as a whitewashing of Cleopatra, denying her the African-ness many people now see as central to this historical figure’s identity. Perhaps the dark stone statue in the Rosicrucian Museum, with its serious demeanour and confident Egyptian stride, seems more securely black and African because of its outward appearance, an Egyptian Cleopatra rather than a Greek or American one – but even it has a tenuous identity: possibly Cleopatra VII, possibly one of her regal predecessors. Made almost two thousand years apart, neither statue is transparent in our contemporary world, though analysing the context in which the statues were first made and used can go some way towards helping us understand their makers’ original intent. Cleopatra was and is mutable, like any aspect of the long-lost past. We can never find her, only traces of her glimpsed in an occluded glass. Not-quite-naked and not-yet-dead, Cleopatra fits a fantasy ‘ancient Egypt’ that is of very modern making.