SIX

VIPERS, VIXENS AND THE VENGEFUL DEAD

|

SIX |

Associated with one of the most alluring figures from Egyptian history, the contrasting statues that closed the last chapter indicate the gulf between ancient and modern ideas of queenship. Cleopatra’s suicide after her defeat by Rome often marks the ‘end’ of ancient Egyptian civilization in conventional chronologies. Since her reign post-dates Manetho’s Aegyptiaca, this is a dividing line modern scholars have drawn, based on a distinction between Egypt as a country governed from its own territory and Egypt as a province answerable to central powers elsewhere. This distinction owes much to ideas of nationhood formed in the eighteenth century and applied, violently, in the nineteenth century and ever since. In the transition from Ptolemaic to Roman rule, however, the violence we remember most today is the violence of Cleopatra – and Antony – against themselves, through their suicides. To the victor goes the claim of restoring and maintaining peace.

With its heady mix of sex and death, the Cleopatra legend is revealing for what it says about Western attitudes to Egypt – and to women. Any well-known historical personage will be interpreted in different ways over time, but Cleopatra’s alleged sexual bewitching of respectable Roman men has had an especially powerful hold over cultural imaginations. Her suicide is the comeuppance for a woman so intelligent that she could (almost) succeed in a man’s world, and so beguiling that men were powerless to resist her. Misogyny seeps through this spin on the bare historical facts. Cleopatra’s womanhood had already been used against her in the propagandistic Roman accounts that circulated during her lifetime and just after her death, written by poets and politicos loyal to the one-time Octavian, newly declared princeps and later emperor Augustus. Some of these slanderous and salacious attacks had been familiar to European audiences since the Renaissance, as had more circumspect, but still colourful, episodes of her biography relayed by the Greek scholar Plutarch in his lives of Julius Caesar and Mark Antony, which were written around AD 100. As a woman and a foreigner, Cleopatra did not warrant her own ‘life’. To the victor goes also the right to write history.

This chapter takes Cleopatra as a starting point for considering how it is that sexpots, sorcerers and mummies have come to dominate our recovery of a ‘lost’ ancient Egypt, especially over the past 150 years. While historical evidence and archaeological finds contribute to ideas about Egypt – the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb, for instance, or the supposed DNA identification of mummified bodies – different eras seem to get the ancient Egypt they desire, or deserve. The literary scholar Edward Said characterized colonial-era European discourse about North Africa, the Middle East and South Asia as Orientalism, an imagined conception of ‘the Orient’ that constructed these places and their inhabitants as everything opposite to how Western cultures saw themselves: lazy where the West was hard-working, dirty where the West was sanitized, disorganized where the West was efficient, trapped in time where the West was modern, and morally suspect where the West was disciplined in matters both sexual and pecuniary.1 While Said’s critique has been challenged or refined in many ways over the years, its central tenet is valuable for reminding us that we have inherited stereotypes about the ancient and more recent pasts of Egypt (and elsewhere) that reflect the concerns of the dominant powers of the day. For every voracious queen and bare-breasted goddess, egomaniacal pharaoh or rampaging linen-wrapped corpse, we should be asking, whose story, what evidence, and why did it appear on our cultural horizon when it did? Perhaps losing ancient Egypt has led us to find parts of ourselves we might be better off without.

The vogue for paintings inspired by ancient Egypt, like those of Alma-Tadema, Poynter and Long, was not limited to Britain by any means. It was widespread throughout Europe and wherever artists trained in European-style painting. Scenes from ancient history were often a sideline of painters who specialized in the so-called Orientalist style (the nineteenth-century term repurposed by Said), which favoured North African and Middle Eastern subjects such as crowded, crumbling streetscapes; markets, mosques or desert caravans; and the ever-popular harem or hammam, both of which offered an excuse for painting naked women. These subjects owed just as much to painters’ imaginations as did their depictions of ancient Egypt or the Holy Land. No one painted the new railway stations of Cairo and Damascus, for instance, or upper-class Egyptian ladies dressed in the latest Parisian fashion. Like the props in Alma-Tadema’s studio or the antiquities he studied for his paintings, time could be mixed and matched or shifted around, so that Egypt was never allowed to be as modern or ‘advanced’ as the West – and for women, even royal women like Cleopatra, clothing was optional.

European artists had been depicting Cleopatra for centuries, and earlier images of her make for an interesting contrast with later versions in the Orientalist mode. With little direct knowledge of Egyptian sites or antiquities to go on, painters tended to treat Cleopatra as they would any other figure from ancient history. Both her suicide, recounted by Plutarch, and her love of luxury, emphasized by Pliny the Elder, inspired the choice of scenes. The seventeenth-century Bolognese painter Guido Reni painted several versions of Cleopatra gazing heavenward as she clasped an asp to her décolleté, but he also used Cleopatra as a portrait mode for the wives of patrons who no doubt wished to be associated with her vast wealth. About 1744 Giambattista Tiepolo painted a cycle of frescoes showing episodes of Cleopatra’s life from both Pliny and Plutarch. Decorating the reception hall of the Palazzo Labia, Venice, these frescoes likewise emphasized the Egyptian queen’s riches and munificence, a luxury to which the successful merchants of this key trading port with the East could easily aspire. Tiepolo depicted Cleopatra, and all the other figures in the frescoes, as a noblewoman of his present day, elaborately costumed, coiffed and bejewelled. The only gesture to the ancient setting of the scenes was the Classical architecture, fitting to the genre of history paintings in the eighteenth century and to the era in which Cleopatra lived.

Before the Napoleonic expedition and subsequent opening of Egypt, artists in Europe had had few references for ancient Egyptian buildings and works of art, apart from obelisks, a few sculptures and small objects in old princely collections. As we saw in the last chapter, the appearance of Vivant Denon’s travel account, and many others, provided ample source material for artists to copy and adapt, as did the eventual publication of the Description. Artists who travelled to Egypt themselves – like David Roberts, whose paintings sold well as prints, or Owen Jones and Joseph Bonomi, designers of the Crystal Palace’s Egyptian court – not only furthered wider public ideas about what ancient Egypt (or what was left of it) looked like, but they added to the visual ‘library’ of sand-drifted temples and hieroglyphic excess. No surprise, then, that artists began to exploit this material to depict Egyptian subjects, including Cleopatra. Yet paintings from around the 1830s onwards went much further, operating in the new Orientalist mode to depict the ancient world in an exotic register that rendered it not so much timeless as atemporal, removed from historical time altogether.

In the Orientalist imagination, the Middle East and its ancient pasts were ripe for fantasy: bourgeois, heterosexual male fantasy in particular. Titillating canvases were a speciality of one of the most prolific and renowned of the Orientalist painters, Jean-Léon Gérôme. Gérôme also painted Classical myths and scenes from French history, including several commemorating Napoleon’s Egyptian campaign, as the disgraced emperor’s reputation revived during the Second French Empire of Napoleon III. But his paintings of ‘Oriental’ subjects, such as snake-charmers, desert scenes, slave markets and Turkish baths, were Gérôme’s most popular, especially since the ‘slaves’ and bathers were invariably beautiful, light-skinned, nude women. For his painting Cleopatra before Caesar, exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1866, Gérôme depicted an episode from the Greek scholar Plutarch’s account of Julius Caesar’s career. Plutarch recounted the first meeting between Caesar, a Roman politician and general, and Cleopatra VII, the Ptolemaic queen who was then embroiled in a civil war with her brother and co-ruler of Egypt, Ptolemy XIII. Rome had long intervened in the dynastic struggles of the Ptolemaic kings and queens, and in 47 BC Caesar came to Egypt to turn the conflict to Rome’s advantage. According to Plutarch, the teenaged Cleopatra had herself smuggled past Caesar’s guards in a cloth sack, so that she could meet with him in person and plead her case. Later translations turned the sack into a ‘carpet’, hence Gérôme painted the young queen surrounded by an Oriental rug – and wearing a dress that leaves the royal breasts entirely bare. What Roman general could resist?

Engraving after a detail of Jean-Léon Gérôme, Cleopatra and Caesar, 1866, oil on canvas.

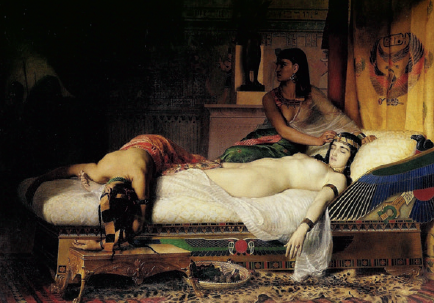

Other painters used Cleopatra’s suicide as the basis for revealing this tempting flesh, painted creamy white in contrast to her dark hair and eyes, making the queen an ‘Oriental’ beauty on the pale end of the spectrum to which nineteenth-century artists were so attuned. In the Gérôme, for instance, Cleopatra’s light skin and petite features contrast with the dark skin, heavy brow and protruding jaw of the servant who has carried her in the carpet roll, and whose African features matched nineteenth-century expectations of servitude. Suicide scenes sometimes created a similar opposition between Cleopatra and her female attendants, Iras and Charmian. The two could be shown as dark and ‘Egyptian’ in contrast to the queen, or as light-skinned and ‘Greek’ like Cleopatra. In Jean-André Rixens’ The Death of Cleopatra, first exhibited in 1874, the painter adopts a middle way, painting Cleopatra with whiter skin than her slightly more tawny handmaidens but leaving us to question whether this is because she is more ‘Greek’ than they are – or because she is dead. On a gilded bed florid with Egyptian swags and carvings, the gleaming body of the queen lies inexplicably naked save for her jewellery and hair adornments. Displayed for viewers like a lurid trophy, the posthumous version of the living humiliation Cleopatra feared at Roman hands, the last of the Hellenistic monarchs is reduced to a dead yet delectable body.

Jean-André Rixens, The Death of Cleopatra, 1874, oil on canvas.

In this Orientalist-influenced history painting, Rixens engages with the long cultural lineage of the Cleopatra legend and its artistic representations. But his dead, not dying, queen should also be seen within the context of those other dead Egyptian bodies that had been revealed to view with increasing focus and frequency over the course of the preceding century: mummies, whose own allure shifted from the sexual to the sinister the more invested Western powers became in modern Egypt’s body politic.

What happened to the corpse of the historical Cleopatra remains a mystery. Her fellow Ptolemaic dynasts had adopted some version of the embalming and wrapping treatments perfected in Egypt for the ritual mummification of the dead, especially the ruling classes and influential elites. The Ptolemies’ Macedonian precursor, Alexander the Great, had already been embalmed in some form when he died on campaign in Persia. His friend Ptolemy, founder of Cleopatra’s dynasty, diverted the leader’s body to the city Alexander had founded in Egypt, Alexandria, and it is possible that some sort of dynastic tomb on the eastern outskirts of the city housed the burials of the royal family, and perhaps even Alexander himself.2 When Octavian entered Alexandria after Cleopatra’s death, he is reported to have visited Alexander’s tomb but declined to view the Ptolemaic crypts, dismissing them as unworthy of his attention and thus aligning himself instead with the glorious victories of Alexander. Whatever Octavian permitted as funeral rites for the defeated queen, Cleopatra’s body does not survive, only the images artists have conjured over the centuries.

Plenty of other bodies did survive from ancient Egypt, however, thanks to the use of mummification. The practice of arresting the decay of the corpse by desiccating it, anointing it with oil and wrapping it in linen had been a hallmark of Egyptian civilization since ancient times, and today mummies are one of the first things the word ‘Egypt’ conjures in people’s minds. In the fifth century BC Herodotus appears to have seen bodies before they were wrapped, or else older examples unwrapped for his benefit, since he comments on the astonishing preservation of their facial features, down to the eyelashes. With information gleaned from the Egyptians he spoke to (in Greek) Herodotus outlined three methods of mummification based on different price bands.3 The most costly process involved eviscerating the corpse through a slit the embalming priests made in the left side of the abdomen; the embalmers extracted brain tissue through the nasal cavity. The corpse was then packed in a salt compound called natron, which formed on evaporated salt lakes in the desert fringes, and the desiccated body was packed and coated with sweet-smelling, resin-infused oils. The final part of the process involved wrapping the corpse finger by finger and limb by limb in several dozen layers of linen bandages, pads and sheets of cloth – some of which, we now know, derived from the clothing the deceased had worn in life and cloths used to wrap divine statues in local temples. Many Egyptian garments comprised wrapped skirts, dresses and mantles, and wrapping or dressing the statues of the gods was the focus of the daily ritual priests carried out for them, so that the statue would have fresh clothing each day.4 In less expensive versions of embalming, Herodotus wrote, less effort went into both the wrapping and embalming stages; one option was to inject turpentine into the abdomen through the anus, with the effect of partly dissolving the inner organs and slowing down decomposition.

Herodotus’ Histories circulated widely in the ancient world and, since their rediscovery in the early sixteenth century, throughout Europe and beyond. His account of mummification thus exerted a powerful influence on ideas about ancient Egypt and about this distinctive practice, as did the Old Testament tale of Joseph, whose elderly father joined him in Egypt and was embalmed and buried with Egyptian rites. Such an elaborate treatment of the dead body (the entire process took seventy days) and the efforts apparently made to preserve the corpse in a lifelike form, contrasted sharply with Islamic, Jewish and Christian burial practices. In medieval and early modern times, mummies had a value beyond this curiosity, however, because ground-up mummy was recommended for medicinal use. Medieval Arabic scholars such as Avicenna (Ibn Sina, who died in 1037) recommended mummia for almost everything, although Avicenna himself did not stipulate Egyptian mummia for the purpose.5 Dissolved in liquid, the mummia (from the Persian for bitumen) was swallowed as a treatment for stomach and liver disorders in particular. A brisk trade in mummia operated between Europe and the Middle East, with ancient body parts extracted from the cemeteries around Cairo and pulverized. There was ample scope for trickery, too, using fresh corpses hastily ‘mummified’ and coated in bitumen or pitch to meet demand. Rumours were rife about criminals’ executed bodies being pickled, dried and ground to be passed off as the authentic article. Such suspicions about adulteration of the product led several doctors and writers in Europe to decry the practice of mummia consumption, which began to fall from fashion in the seventeenth century. Ingesting mummia amounted to cannibalism, always an uncomfortable thought. It also commoditized the human body, a concern raised for the contemporary slave trade as well. As the eminent English physician Sir Thomas Browne put it, ‘Mummy is become merchandise, Mizraim [Egypt] cures wounds, and Pharaoh is sold for balsam.’6 Browne wondered where this exploitation of the dead would eventually lead, if left unchecked.

It was no coincidence that one of the first recorded mummy unwrappings and dismemberings to take place on European soil was undertaken by the German pharmacist Christian Hertzog, in Gotha in 1718.7 Mummies had been collectors’ items since the sixteenth century, when the Italian adventurer Pietro Della Valle recounted his explorations in the Saqqara cemeteries near Cairo, where he chiselled ‘bitumen’ (in fact, hardened resin) off a mummified head and brought two beautifully decorated, wrapped-up mummies back with him. In the noble and princely collections known as cabinets of curiosity (Wunderkammern), mummies – both human and animal – were prized specimens. The painter Peter Paul Rubens owned one, and Athanasius Kircher avidly studied, through drawings and correspondence, a mummy in the collection of the Grand Duke of Tuscany.8 In 1705 the English surgeon Thomas Greenhill made a close study of all the available literature on mummification to date in hopes of proving that embalming was ‘no less ancient and noble than Surgery itself’.9 Greenhill thought the English should adopt the practice for hygienic reasons and that surgeons, rather than undertakers, were best qualified to perform it for aristocratic clients.

As medical training became more structured and professionalized over the course of the eighteenth century, access to corpses for anatomical investigation became more important. Understanding the inner workings of the human body united surgeons and physicians, who otherwise had distinct identities. At the same time, natural scientists began to consider human difference in the far-flung regions that European colonialism encountered. Egypt sat at the juncture of Africa, the Middle East and the Mediterranean, and it was well known to educated Europeans through ancient Greek and Roman authors. Where the ancient Egyptians, in particular, fit into the emerging ‘science’ of race was a question that anatomists proved eager to explore in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, exactly the time when the Napoleonic expedition had made the supply of antiquities (and mummies) from Egypt much easier, and more desirable. Leading scientists of the day, including Johann Friedrich Blumenbach in Germany and Georges Cuvier in France, drew different conclusions about the supposed racial identity of the ancient Egyptians: closer to the Caucasian race, thought Cuvier; Ethiopian, argued Blumenbach, using one of the terms applied to African peoples in these early schemes.

The idea of different races and fixed racial characteristics soon led to the creation of a hierarchy whereby some races were superior to others: the basis of what became scientific racism, a ‘science’ put to sinister use. In the early nineteenth century successful campaigns against the slave trade created an environment in which, paradoxically, scientific racism became entrenched, for instance among advocates of a slave-based economy in the southern United States. Slave-owners and some scientists seized on racial classification to justify the enslavement of Africans, who were deemed less intelligent and considered ‘childlike’ or ‘primitive’. The most extreme form of this argument was the theory of polygenesis, which held that humans were not a single race, but several. In the 1850s the American Egyptologist George R. Gliddon, who had spent much of his life in Egypt, and the Alabama physician and slave-owner Josiah Nott published a multi-volume book called Types of Mankind, which went into several printings in the decade leading up to the American Civil War.10 Nott and Gliddon used not only the skulls of mummies but examples of ancient Egyptian art to argue that the ancient Egyptians were a Caucasian society that used black, African (‘Negroid’) slaves as a workforce, from domestic servants to physical labourers. The American South was heir, in this view, not only to the Classical cultures of Greece and Rome – think of all those columned plantation houses – but to the great civilization of Egypt, which it deemed a slave-holding society parallel to its own.

It might be reassuring to imagine that these race-based interpretations of ancient Egyptian civilization were fringe ideas, but so pervasive were assumptions about human differences in the nineteenth century that no area of cultural life was immune from them, including the academic study of the past. Comparative anatomy informed all studies of humankind, from biology and anthropology to history and archaeology. Physical differences between humans were mapped against perceived cultural differences to create schemes of progress, with asserted European or Caucasian accomplishments always coming out on top. It is important to understand how widely accepted ideas about anatomy, mummies and race were in Egyptology and archaeology, which established themselves as full-fledged academic disciplines in the latter nineteenth century. One of the founding fathers of the discipline, W. M. Flinders Petrie, actively engaged with physical anthropology research, collecting skulls from his fieldwork to send to colleagues in the UK, including the eugenicist Francis Galton.11 The rest of the bodies he found were reburied en masse at excavation sites, and the same is true for other excavations of the time. Petrie used the results of anatomical analyses to concoct race-based theories, such as his idea that prehistoric Egyptian civilization had only attained a certain level of accomplishment – late in the Naqada period – when a ‘Dynastic Race’ of people from the Levant moved into the Nile Valley and introduced innovations in materials, technologies and societal organization. In other words, the influence of a northern ‘race’ superior to the indigenous population was essential to any advance in forming the society Petrie and other Egyptologists recognized as ‘ancient Egypt’. Petrie also compiled a photographic dossier of ancient Egyptian art representing the different cultural groups the Egyptians had encountered, from the Libyan deserts, Nubia and the upper reaches of the Nile, and the Levantine coast and Anatolia. In ancient Egypt, especially during its own period of military and trade expansion in the New Kingdom, visual representations of different ‘types’ were an essential contrast to the Egyptian elite’s representation of themselves. These Libyan, African and West Asian peoples were also the conventional enemies of the Egyptian pharaoh, who trampled them underfoot and bashed them over the head in innumerable artistic scenes. Ancient Egyptians had their own ‘others’ – but to try to make their constructions of difference correspond to our own invites false comparisons, though it does say something about the long history of how societies divide themselves into ‘us’ and ‘them’.

The unwrapping and anatomical investigation of mummies reached its peak in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, corresponding to peaks both in the intensity of archaeological investigation in Egypt and in the widespread interest in investigating racial typologies, sexual characteristics and traces of disease. In the years around 1910 the Australian-born professor of anatomy Grafton Elliot Smith carried out exhaustive studies of the mummified bodies of many famous pharaohs, queens and priests, who had been found re-buried in caches in the Deir el-Bahri cliffs and the Valley of the Kings. He defended his research, and the ethical dilemmas it raised, in the preface to his published catalogue, arguing that ‘modern archaeologists, in doing what they have done, have been rescuing these mummies from the destructive vandalism of the modern descendants of . . . ancient grave-plunderers. Having these valuable historical “documents” in our possession it is surely our duty to read them as fully and as carefully as possible.’12 In the catalogue of the mummies, where he ‘let the naked bodies tell their own story’, Smith’s scientific language created an aura of authority and objectivity, as it was intended to, but read in close detail his observations on the skin colour of the mummies, the high-bridged (that is, Caucasian) noses of the Ramesside kings, the breast size and shape of various queens, and the treatment of the genitals of female mummies make for difficult reading today, if we approach them with a more critical and questioning eye.13

Like other anatomists who worked on mummies, Smith was a product of his age: but what assumptions did that age bring to bear on their research, and how has it continued to influence our own perceptions? Even the idea that mummies should be unwrapped and dissected could be called into question, though it was rarely questioned at the time, and then only where royal mummies were concerned, because they were royal. Few Egyptologists paid much attention to the copious linen wrappings, which were often discarded after the investigation, yet these wrappings were one of the most expensive and significant aspects of the ancient ritual. When examining the condition of the embalmed corpse, for instance when looking for traces of the natron salt, embalming oils, or evisceration and excerebration, the influence of Herodotus loomed large over the anatomist’s table. Smith and others characterized variations from the ‘norm’, or poor preservation of the body, as laziness or incompetence on the part of the embalmers, Orientalizing the ancient Egyptian workers as feckless or financially unscrupulous. If we consider the mummification process in the light of Egyptian ritual evidence, however, a different picture emerges; what goes unsaid or unrecorded becomes a significant point of silence. Tellingly, for instance, the ancient Egyptians themselves say nothing about how to treat the body, while there are extensive descriptions of how to wrap and arrange the linen, and what kind of linen it should be. We also know that the application of purifying, cleansing natron, sweet-smelling resinous oils and freshly woven linen, both to statues and to dead bodies, was held to reawaken them and restore them to life. The idea that the body beneath the linen, which no one but the priests ever saw, was the most significant part of the process and had to be as ‘lifelike’ as possible, casts our own assumptions backwards in time. The end result was what mattered to ancient Egyptians, and it was meant to be hidden away, secured, protected, inviolable and beyond all human view. Unwrapping the dead went against everything the ancient Egyptians called for in their prayers and ritual texts, as was well known. Small wonder, then, that some anxiety should begin to show about whether the mummies hauled out of their tombs and placed under the surgical knife might some day seek revenge.

The exotic and the erotic have tinged modern imaginings of ancient Egypt with the glow of Orientalism, not only in the fine arts we considered at the start of this chapter, but in the theatre and cinema, public exhibitions, advertising and literature, from the lowbrow to belles-lettres. The world of scholarship does not exist in isolation, and whether it took place in Egypt or in the new research institutes set up across Europe and North America, academic Egyptology was, and remains, in dialogue with these other ancient Egypts. Archaeologists working in Egypt courted press attention to help inform the public about their discoveries, and also to promote their work and emphasize their own authority as interpreters of the past. In turn, press coverage, publications and exhibitions were the visual fodder for wider receptions of ancient Egypt, based on historical figures and facts and recent archaeological discoveries. The scholarly and the scintillating always intertwined: the French Egyptologist Auguste Mariette helped with the scenario for Giuseppe Verdi’s ancient Egypt-set opera Aida, which premiered in Cairo in 1871, while the German Egyptologist Georg Ebers authored a number of popular romances set in ancient Egypt, to bring the finds of his colleagues to greater attention and bring their historical context to life. Between the 1860s and 1890s, Ebers was widely read in his native Germany and his works, including An Egyptian Princess, The Bride of the Nile and Cleopatra, were translated into other European languages, too.

Ebers’s romantic novels made suitable reading for ladies, but other works of fiction inspired by ancient Egypt toyed with headier themes of death and sex. Orientalism in art and writing developed out of the Romantic movement in the 1830s, a ‘back to nature’ – or back to the distant past – reaction to the upheavals of the Napoleonic wars, in which the self-styled artistic temperament sought inspiration from the natural world, far-flung travel or direct encounters with art and ruins linked to antiquity. The French novelist and playwright Théophile Gautier turned his hand to ancient Egyptian themes, inspired by his own travels as well as those of his friend Maxime Du Camp, who visited Egypt from 1849 to 1851 on a photographic expedition organized by the French ministry of education. One of Gautier’s short stories, first published in the 1830s, recounted a stolen night Cleopatra enjoys with an Egyptian servant while Mark Antony is away. Cleopatra longs for passion to counteract the land of the dead over which she rules, an Orientalizing trope for Egypt’s long decline as a country and for the death-obsessed myth of mummification.

Cover of a vocal score for Giuseppe Verdi’s Aida, 1872.

Cleopatra is the sexual predator in the story, initiating her encounter with ‘the native’. Usually it was a European, male protagonist who sought out the ‘Oriental’ woman, although he might also find himself pursued by the desires of the long-dead. Another Gautier short story, ‘The Mummy’s Foot’, set the action in a Paris junk shop, which a young man-about-town, an aspiring writer, visits in search of a paperweight for his desk.14 The elderly shopkeeper, who looks like ‘an Oriental or Jewish type‘, rummages through the shop’s astonishing array of bric-a-brac – Hindu gods, Mexican fetish figures, Malayan weaponry – before the writer spots a ‘charming’ foot, which he at first mistakes for a piece of ancient bronze sculpture, polished to a gleam by thousands of kisses. Closer inspection reveals that the foot is embalmed and unwrapped, with a faint impression of the bandages in the surface of the skin. The merchant tells him that the foot belonged to an Egyptian princess named Hermonthis – and warns him that her father, the pharaoh, would not be pleased to see it turned into a paperweight.

Undaunted, the young man returns home and proudly places his new purchase on top of a pile of his unfinished writing, to ‘charming, bizarre, and romantic’ effect. That night, after a drunken meal with friends, he enters his apartment to find that

a vague whiff of Oriental perfume delicately titillated my olfactory nerves. The heat of the room had warmed the natron, bitumen, and myrrh in which the paraschistes, who cut open the bodies of the dead, had bathed the corpse of the princess. It was a perfume at once sweet and penetrating, a perfume that four thousand years had not been able to dissipate. The Dream of Egypt was Eternity. Her odours have the solidity of granite and endure as long.

In his heavy, champagne-induced and perfume-ridden sleep, the writer dreams that he sees the foot scuttling and jumping across his desk. His bed curtains open to reveal a young woman ‘of a very deep coffee-brown complexion’, with almond-shaped eyes but a nose ‘almost Greek in its delicacy’. The woman and her missing appendage strike up a conversation, in which the foot informs Princess Hermonthis that it has been sold by ‘the Arab’ who robbed her tomb. At this, the writer – still in a dream – relinquishes his ownership of the foot, which the princess happily fits back onto her leg. The writer and the princess travel as if by magic to an ancient Egyptian underworld, where her father, the king, rejects the writer’s marriage proposal on the grounds that the Frenchman is too soft, too mortal. Finally the writer is abruptly awoken to find that in place of the mummified foot, the Egyptian amulet that Hermonthis wore in his dream now sits on his desk: a much safer, if less exciting, paperweight.

Such gothic adventures are undoubtedly entertaining, and Gautier’s tongue may be in his cheek as he describes his fictional alter ego’s adventure with the slender-footed princess. However, stories like ‘The Mummy’s Foot’ betray the extent to which stereotypes of the ancient and modern Middle East are embedded in the foundations of our contemporary world.15 Readers shrink now from the racist characterization of the shopkeeper as ‘an Oriental or Jewish type’, yet the idea of the thieving, untrustworthy Arab is alive and well, from successful Hollywood films like The Mummy franchise to right-wing news commentary on political and military unrest in Arab regions, where antiquities are increasingly under threat – arguably at least in part because of the bitter histories that associate them with Western concerns. In the story, the writer is powerless to resist the lure of Egypt, which acts on him through its perfume, its sheer endurance, and of course its beautiful women, whose dark complexions and almost-Greek noses combine the exotic and familiar, like ancient Egypt itself. How surprisingly little some things have changed, given that today’s museum gift shops stock ‘Egyptian’-inspired scents for the home and ‘Oriental’ glass bottles for perfume.

Other things did change, of course, and as Egypt became a cause of financial and military concern for Europe’s imperial powers, its fictionalized mummies began to turn more threatening than the amiable Princess Hermonthis.16 In the late nineteenth century, following Britain’s invasion and occupation of Egypt, British (at that time including Irish) authors as diverse as Bram Stoker, Arthur Conan Doyle and Rudyard Kipling began to depict archaeological encounters with ancient Egyptian remains less as a source of sensual enticement and more as a haunting with malevolent intent. With its veils lifted and its shrouds unwrapped, the Egyptian mummy began to fight back against its violators in fiction, just as contemporary Egyptians were demanding less interference from foreign interlopers in real life. Confidence in the values and justice of British imperialism may have been unwavering on the surface, but tales of endangered excavations, doomed adventures and cursed disturbances speak to the anxieties simmering underneath.

No writer exemplified this genre more than H. Rider Haggard, who drew on his early career in South Africa, then a British colony, to write immensely successful stories and novels set in colonial locales, including King Solomon’s Mines, She and its sequel, Ayesha. Rider Haggard popularized the ‘lost world’ genre, a precursor of science fiction in which contemporary characters discover an ancient culture living in isolation, entirely cut off from the outside world and its way of life thus preserved. It should have been the archaeologist’s dream – but often became the stuff of nightmare. The act of breaching this present past disturbed the balance of the lost civilization, unleashing its dark forces on the British protagonists and their loyal, native servants. In She a Cambridge professor and his ward, handsome blond Leo, stumble across a remote African civilization of dark-skinned people ruled by the white-skinned queen Ayesha, known as ‘She-who-must-be-obeyed’. Ayesha has lived for two millennia using her magical power, and in Leo she thinks she has found the reincarnation of her Greek-Egyptian lover, Kallikrates, whom she once killed in a fit of rage. Beautiful but poisoned by lust and vengeance, Ayesha gets her inevitable, fatal comeuppance in the end – at least until Rider Haggard brought her back to life in the sequel. To complicate matters further, Leo turns out to be a descendant of Kallikrates and the Egyptian priestess Amenartes, who wrote out their ill-fated story on a potsherd – which Rider Haggard had recreated, and which his family later donated to their local museum in Norwich Castle. The character of Leo, the quintessential Englishman, is thus an ancient Egyptian with a bit of Greek blood for good measure, while Ayesha, the white-skinned queen, is the wilful oppressor of her African people. Questions of race were central to the Victorian world-view – and no less complicated for it.

An inscribed potsherd made by H. Rider Haggard’s sister to match the plot of his best-selling novel She, published in 1887.

Another Rider Haggard story, ‘Smith and the Pharaohs’, combines romance, archaeology and mystery in the setting of two famous museum collections of Egyptian antiquities: the British Museum in London and the Egyptian Antiquities Museum in Cairo, which had recently moved to the building it still occupies in Tahrir (then Ismailia) Square.17 First published in The Strand Magazine in 1913, the story echoes reservations that Rider Haggard himself expressed about the excavation, unwrapping and display of Egyptian mummies, and of royal mummies in particular. The eponymous Smith is a successful businessman who ducks into the British Museum to escape the rain and falls head over heels for the sculpture of an ancient Egyptian woman, mounted on a gallery wall. Informed that the sculpture is a cast, and the original (‘Mariette found it, I believe, at Karnac’) is in Cairo, Smith immerses himself in Egyptology and journeys to Egypt to train with archaeologists there. Eventually granted his own excavation permit under the usual terms, namely that the antiquities department could keep whatever they wished, Smith commences work at Thebes and muses under the moonlight:

The mystery of Egypt entered his soul and oppressed him. How much dead majesty lay in the hill upon which he stood? Were they all really dead, he wondered, or were those fellaheen right? Did their spirits still come forth at night and wander through the land where once they ruled?

Smith’s efforts are rewarded with the discovery of the tomb of the beautiful – and fictional – 18th Dynasty queen Ma-mee, though the royal mummy is missing apart from one elegant, bejewelled hand, which Smith wraps safely and stores in a cigar box. Back in Cairo, Smith discusses the find with both the French head of the antiquities service and the museum director, also French: Rider Haggard was clearly well informed about how archaeology worked in Egypt, from his own research, travels and acquaintance with British Egyptologists. After their meeting, Smith wanders the halls of the museum, ruminating again as he studies the royal mummies on display. So absorbed in his reflections that he misses closing time, Smith has to spend the night asleep in the museum with the mummies where, like the hero of Gautier’s story, he too dreams of ancient Egypt. The rulers of Egypt, from Menes to Cleopatra, address him, to ask his help in avenging the violation of their tombs – until the mummified hand in his pocket clatters to the floor, revealing Smith as no better than a thief himself. With the help of Queen Ma-mee, whose hand it is, after all, Smith defends himself against this charge by arguing that it was his love for ancient Egypt that led him to excavate and to preserve his discoveries in the museum. The pharaohs let Smith off the hook: his violation was done in ‘reverent ignorance’, and the real thief, they decide, is the Egyptian priest who first broached Ma-mee’s tomb with greed and lust in mind. When Smith awakens, he finds on his finger a gold ring with Ma-mee’s name and knows that they were lovers in the past, now separated forever. Smith, consequently, abandons Egyptology.

In this story Rider Haggard questions the aims and methods of archaeology even as he accepts their essential premise, for the immortal love between Smith and Ma-mee asserts a Western or British ‘right’ to possess Egypt just as strongly as archaeology did. The long-lost queen – beautiful and sweetly perfumed, of course – exists most vividly in Smith’s dream vision, but in reality she survives through the objects displayed in London and Cairo, without which Smith would never have encountered (or re-encountered) her. The pharaohs themselves absolve Smith of conscious wrongdoing in his archaeological research, blaming instead another Egyptian through the menacing figure of the priest. At the end of the story, Smith – and Rider Haggard – professes uncertainty over what exactly happened that night in the museum. But the seed of doubt was planted: what did the Egyptians – ancient and modern – think of these foreigners poking around in their business?

Harry Burton, photograph of the antechamber of Tutankhamun’s tomb taken shortly after its discovery, December 1922.

The First World War reconfigured the eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East forever, as the victorious powers unstitched the old Ottoman Empire. In 1919 both peaceful and violent protests accompanied Egyptian attempts to negotiate self-rule, which met with limited success. Rather than continue negotiations, the British government unilaterally granted limited powers to the Egyptian government in 1922. Egypt’s first free elections swept a nationalist political party, the Wafd, to power just months before Howard Carter discovered the tomb of Tutankhamun. At a time of pitched politics, the astonishing discovery of an almost untouched royal tomb seemed like the stuff of fiction and was embraced fervently in the Western press as much as within Egypt. To the newly independent state, the reawakened Tutankhamun was a powerful symbol of the Egyptian nation reawakening after centuries of rule from outside, and Egyptian poets wrote paeans to the boy-king, which we consider further in Chapter Eight.

But amid the excitement of the find, tensions quickly arose around the immediate issue of who should represent it in the press: Carter and his patron, Lord Carnarvon, or the Egyptian antiquities officials? In the background loomed the larger issue of whether the finds from the tomb would wind up in the Cairo museum or be divided between Cairo and Carnarvon. Times had changed faster than Carter and Carnarvon realized, and the days were long past when the Egyptian government, including the antiquities service still headed by French specialists, would yield such a major discovery to a foreign collector.18 The first photographs taken inside the tomb hinted at the ‘wonderful things’ that filled the first room – and at the treasures behind the sealed doorway waiting to be found. Tourists flocked to the scene and famous visitors, including Rider Haggard, enjoyed personal tours of the work in progress, although their presence inevitably disrupted progress on the work itself.

When Carnarvon, weakened by years of ill health, succumbed to sepsis in April 1923, just as the first season of excavation was drawing to a close, the Western press had decades of fictional and political drama to call on in painting his death as Tutankhamun’s revenge, the ‘curse of the pharaohs’ writ large. This personal tragedy did nothing to smooth over the tensions brewing between Carter and the antiquities department as work on the tomb progressed, which centred on the preferential access Carnarvon and Carter gave to the London Times. Finally, just after he had raised the lid of the royal sarcophagus in the second excavation season, Carter downed tools and the antiquities department reclaimed control of the tomb. After a year’s break – and a change of government in Egypt, more acquiescent to British interests – Carter and his team returned to work. By the time the royal mummy was ready to be unwrapped, press coverage had become, mercifully, more subdued. Carter led calls to treat the royal remains with ‘reverence’, mindful of the new political landscape as well as the specific concerns that had always surrounded the treatment of royal bodies, as if they were more deserving of careful treatment than any other mummified remains. In fact, the remains of the king had to be chiselled bit-by-bit out of his coffin, where the wrappings were stuck fast with resin. To extricate the heavy gold mummy mask, Carter and his colleagues detached the head from the body and used heated knives to prise it from the mask. The hands were detached to remove the royal rings and bracelets, and the lower legs, feet and pelvic bones likewise, since all were photographed separately.

In the autumn of 1926 the disarticulated mummy of Tutankhamun was rearranged in a tray of sand, rewrapped and replaced in its sarcophagus, within the otherwise emptied burial chamber of the tomb. It was intended, finally, to be an eternal rest for the boy-king – but both the mummy and the alleged curse would be brought back into the light repeatedly in the coming decades.19 Each time someone associated with the original excavation died, their lifespan was measured against the likelihood of pharaonic interference, and a series of blockbuster museum exhibitions in the 1970s and the 2000s sparked new theories about Tutankhamun’s life and legacy. Tutankhamun’s mummy is still in the tomb, but not in the sarcophagus, out of sight. In 2007 the Egyptian authorities installed a specially commissioned museum case in the burial chamber, so that the remains could be displayed in a climate-controlled environment. Any curse, it would appear, is on Tutankhamun himself, who cannot rest, thanks to the lost civilization he now represents.