SEVEN

OUT OF AFRICA

|

SEVEN |

Two glimpses of ancient Egypt through the lens of contemporary media: first, right-wing news magnate Rupert Murdoch’s Twitter account, where in November 2014, he felt moved to comment on the Hollywood blockbuster Exodus:Gods and Kings, which some Twitter users and web bloggers had criticized for its all-white cast. ‘Since when are Egyptians not white?’, tweeted Murdoch, adding that all the Egyptians of his acquaintance were. Glimpse two, the pop star Rihanna’s Instagram feed in 2012, where the much-tattooed singer revealed her latest ink: the goddess Isis with outstretched wings, the sweeping lines of which follow exactly the curved underside of Rihanna’s breasts. Rihanna also has two other ancient Egyptian-themed tattoos (the bust of Nefertiti, on the left side of her ribs, and a falcon on her left ankle), among other ‘exotic’ inkings such as Arabic, Sanskrit and Tibetan expressions. Rihanna herself has commented only that the winged Isis commemorates the death of her ‘guardian angel’ grandmother, but some Rihanna-watchers associate the Isis and Nefertiti tattoos with the singer’s black identity: one African beauty adorning her body with others.

Since many people who would identify as white also have ancient Egyptian tattoos, reading race into Rihanna’s choices exemplifies the pigeonholing to which black – and female – artists are so often subject. But taken together with Murdoch’s tweet (which plenty of other Twitter users lampooned), the possibility that an ancient Egyptian-themed tattoo might refer to black or African heritage speaks volumes about how large the issue of race looms in our own society, and how intrinsically ancient Egypt is entangled in it. Rupert Murdoch is happy to identify the modern Egyptians of his acquaintance as being just-like-him in racial terms, and many people in North Africa and the Middle East do have pale skin and blue eyes, two of the physical attributes associated with a ‘white’ or Caucasian racial phenotype. Egyptians themselves distinguish different skin tones, facial features and hair textures, for instance identifying darker skin tones with the southern reaches of the country (conventionally seen as rural and backwards, like hillbillies in American lore), and the very darkest skin tones with Nubia near the border with Sudan. The cultural weight given to these kinds of distinctions is another matter, however. Difference translates into prejudice and inequity where factors like economic exploitation have shaped power dynamics within and between societies. Decades after the break-up of empires and the overthrow of racist regimes in the American South and Apartheid South Africa, deep-rooted anxieties about race are a fact of contemporary life, and ancient Egypt is their proving ground.

By this point, readers might be able to anticipate my own observation here: more than personal identities or idiosyncrasies, it is cultural memory – and forgetfulness – that determines what someone assumes an ancient Egyptian looked like, or why anyone, of any identity, wants an ancient Egyptian deity inked into her skin. More than any other lost civilization, ancient Egypt inspires heated debates about race, and for good historical reasons: when the concept of human racial differences was first formulated in Europe in the late eighteenth century, European powers were eyeing up Egypt’s strategic position between the Mediterranean and the Red Sea. At the same time, European thought had begun to embrace ancient Egyptian culture as reimagined, for instance, in Freemasonry, the arts and entertainment. Intrigued by the way Greek and Roman writers described ancient Egyptians – to Herodotus, they were ‘Ethiopian’, with dark skin and tightly curled hair – eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century scholars looked to Egyptian art for clues, based on the antiquities that had started to arrive in Europe in ever greater numbers. But they also, increasingly, looked to the bodies of the ancient Egyptians themselves, since the distinctive practice of mummification made these corpses perfect subjects for the new medical men of the era.

Because Western thought had long recognized Egypt as such an important ancient culture, polarized arguments have tried to claim it as both an African/black and a Caucasian/white civilization. Rupert Murdoch is not alone in his ideas. Most public considerations of this topic miss the key points that this chapter will consider, however: first, how ideas about race have been invented and exploited since the eighteenth century; and second, how the traumas of the transatlantic slave trade and colonization helped make ancient Egypt an important touchstone of identity among African diasporas and in several African countries. The chapter opens by considering how race science influenced the study of mummies and the development of Egyptology, which will help us understand how ancient Egypt became a symbol of both pride and prejudice, from the American abolitionist movement to Pan-Africanism. Ancient Egypt has been a source of inspiration for cultural movements like the Harlem Renaissance, which saw artists and literary figures evoke Egypt as a lost African homeland. In post-independence Senegal, ancient Egypt represented achievements with which all Africans could identify, or so argued the Senegalese academic Cheikh Anta Diop, whose work inspired an interpretation known as Afrocentrism that has been especially influential in the United States. Contemporary artists continue to use references to ancient Egypt as a way to confront themes of racial prejudice, Eurocentrism and the dark side of the Enlightenment, with its legacies of colonialism and the slave trade. It appears that Rupert Murdoch and Rihanna have ideas about ancient Egypt with longer and deeper roots than they may realize. But the reaction, interest or admiration their verbal or visual expressions generated indicates that this ‘lost’ civilization exposes our own sensitivities about more recently buried histories.

The question ‘What race were the ancient Egyptians?’ assumes that ‘race’ is a fixed or useful concept: its answer often depends on who is asking it, and why. To understand how ancient Egypt became so entwined with this question, we have to return once again to eighteenth-century Europe, where the notion of ‘race’ was first formulated.1 In the past fifty years biological and social scientists have abandoned race as a category, because the simple physical characteristics it relies on – skin colour, hair type, face shape and so on – do not map on to the kinds of genetic data, such as DNA, that modern techniques enable. The relationship between phenotype (external appearance) and a cline or cluster of genetic traits proves to be highly variable. Whether people identify themselves or others with a certain race profile depends on external appearance as well as social assumptions or expectations. Genetic data can be made to fit these (using DNA evidence to identify someone as Caucasian or East Asian, for instance) but also shows the tremendous variety of human populations, thanks to thousands of years of global migration – including more recent forced movements, such as slavery.

It was contact with other peoples as a result of European expansionism that encouraged eighteenth-century scholars such as Carl Linnaeus, in Sweden, and Petrus Camper, based in Amsterdam, to formulate the first classification systems for human racial difference. Camper measured skulls collected by travellers or derived from anatomical dissections, often using the bodies of criminals. He developed a system of representing heads in profile to show the angles between forehead, nose and jaw, which were meant to indicate the difference between ‘European’ and ‘Ethiopian’ or African types in particular.2 Camper followed a common practice at the time, in comparing the profiles of human remains to the profiles of admired Classical statues such as the Apollo Belvedere in the Vatican. Assuming that the ancient Greeks had attained the pinnacle of realism in art, and that the Greeks were ‘European’, anatomists like Camper saw no difficulty in arranging the profiles of statues and of skulls in hierarchical rows. The statues were the most beautiful and most European, with their straight-up-and-down profile, while skulls that had strong lower jaws or prominent foreheads yielded steeper angles and thus were not European – and not beautiful.

Camper’s influential schema did not consider ancient Egyptian art, since what little was known about it in Europe at the time found it lacking in comparison to Greek art, as we saw earlier. Instead, other anatomists realized that unwrapping ancient Egyptian mummies offered a unique opportunity to study the ‘race’ of an ancient population quite literally in the flesh, something impossible for the ancient Greeks, who practised cremation. In the 1790s the German scholar Johann Friedrich Blumenbach unwrapped Egyptian mummies (some of them fakes sold to early travellers) to augment his research on human variety. It was Blumenbach who coined the term ‘Caucasian’, based on skulls he collected from the Caucasus mountains in Georgia – one of which he described as the most beautiful skull he had ever seen. In the early nineteenth century mummy unwrappings became something of a fad among learned societies and surgeons keen to position themselves as experts in the newly professionalized medical field. The supply of fresh cadavers for anatomical dissection was still restricted, and more mummies were available in Europe in the wake of the Napoleonic expedition (and the end of the ensuing wars). Unwrapping a mummy killed several birds with one stone, so to speak. By the 1820s it was taken for granted that the head of an unwrapped mummy would be measured to determine its racial identity, using the methods Camper had devised and French zoologist Georges Cuvier had further developed. Thus the British-Italian surgeon Augustus Bozzi Granville confidently announced to the Royal Society in London that a female mummy he unwrapped was Caucasian. Granville noted that Cuvier also considered the ancient Egyptians to be a Caucasian population, while Blumenbach thought them closer to the Ethiopian race – later known as ‘Negroid’.3

If learned men and medical specialists at first wished to classify human difference as an exercise in itself, pursuing a new form of knowledge in the Enlightenment spirit, it was nonetheless the case that the idea of racial difference soon became an instrument for racial prejudice. In 1830s Philadelphia, physician Samuel Morton made his own forays into race classification, using hundreds of skulls. His collection included the skulls of Native American peoples and skulls from ancient Egyptian mummies, the latter supplied from Egypt by the British-born American consul there, George Robbins Gliddon. Using lead shot, Morton measured the volume of skulls he had assigned to different races, and from this he suggested that different skull sizes implied different brain sizes, hence (he assumed) variations in mental capacity. Caucasians were the most intelligent race, while Native Americans were only just above Africans and Aboriginal Australians, who occupied the bottom of his ranking.4 Morton (like Granville) determined that the ancient Egyptians were Caucasian, which rather conveniently fitted mainstream reasoning that Egypt was a great civilization and therefore a white one. Morton also proposed that the differences between human ‘races’ were so significant that humans were not one species but several, a theory known as polygenesis, ‘many origins’. This seems preposterous now, but it was taken very seriously around the mid-nineteenth century, when the African slave trade was still active in the South Atlantic and the cotton and tobacco economies of the southern United States relied on slave labour. Morton’s work became influential among proponents of slavery, such as South Carolina Senator John Calhoun, who argued that all great societies, including ancient Egypt, consisted of an elite who owned slaves as a ‘positive good’ for everyone involved; besides which, the theory of polygenesis argued that enslaved races were from a different species, not true Homo sapiens. Recreating ancient Egypt as a white civilization that owned black slaves, just like the American South, seemed to account for differences among ancient Egyptian skulls and in ancient Egyptian art, which was increasingly acknowledged as representing a range of skin tones, hair textures and physiognomies.

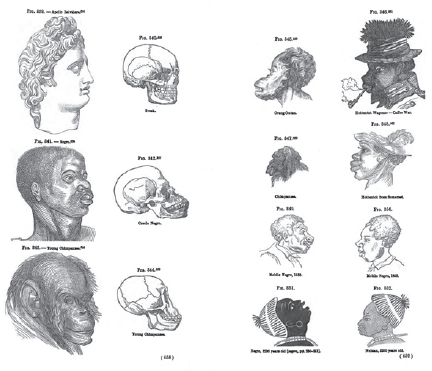

A comparison of racial (and racist) ‘types’, using skulls, sculpture, humans and animals, from Josiah Nott and George Gliddon, Types of Mankind (1854).

After Morton’s death, George Gliddon (his supplier of skulls from Egypt) collaborated with Alabama physician and plantation – hence, slave – owner Josiah Nott to produce a mammoth volume dedicated to his memory, called Types of Mankind.5 First published in 1854, Types of Mankind proved so popular that it was reprinted eight times before the decade’s end. In a chapter devoted to Egypt, Nott and Gliddon echoed the visualization methods of Camper’s work by comparing the Egyptian skulls Morton had studied to hand-drawn copies of Egyptian wall paintings and reliefs in the works of early Egyptologists like Champollion. Some of these depicted captured soldiers or subservient traders with black African features, using a visual rhetoric that proclaimed the supremacy of Egypt over the known world. Nott and Gliddon had to admit, as Morton had, that the original ‘Nilotic stock’ of the ancient Egyptians was no longer ‘pure’ after around 2000 BC – but it was absolutely not ‘Negroid’, they argued, with ‘Negro types’ in Egypt strictly limited to the enslaved stratum of society. No mingling allowed. In mid-nineteenth-century America, anxieties about miscegenation were rooted in contemporaneous realities: the sexual exploitation of black slaves by their white masters was endemic.

Abhorrent theories like Nott and Gliddon’s retreated somewhat, with the end of plantation slavery in the American Civil War and the rejection of polygenesis once Darwin’s theory of evolution gained acceptance. But the assumptions at their core – that Caucasians are the most intelligent race, that Africans had no ‘great’ civilization – have never entirely gone away, living on in the invective of white supremacy and, of course, in cultural memory. Moreover, other forms of race science were fundamental in the development of entire scientific disciplines in the late nineteenth century, and not just biological sciences, but anthropology and archaeology as well. In the wake of Darwin, the idea that whole civilizations, as well as different human populations, were part of an ongoing evolutionary process suffused the thinking of many of the ‘founding fathers’ of these disciplines; and it still slips unnoticed into our own thinking any time we use a word such as ‘primitive’ or ‘backwards’ to describe another culture. One of the most influential figures in Egyptian archaeology, Flinders Petrie, was typical of his day in that his interpretations of the ancient past were steeped in ideas about race. In his studies of Egyptian prehistory, which was then a new field, Petrie theorized that a separate group of people from the north, termed the Dynastic Race, moved into the Nile Valley, intermarried with indigenous groups from the south, and thus catalysed the technological advancement that created ‘civilization’. Petrie’s theory offered a positive outcome to racial mixing, unlike the vitriol of Nott and Gliddon, but it is nonetheless a theory based on false premises – ‘race’ as a meaningful category, and ‘northern’ races as superior. In an echo of Gliddon, Petrie saved skulls he excavated in Egypt to send to his friend (and Darwin’s cousin) Francis Galton, who ran an institute for the study of eugenics at University College London.6 Petrie also compiled photographs of Egyptian art to identify and categorize different ‘races’ in antiquity.

Race science was built into the study of ancient Egypt from the start, from its mummies to its works of art, which approaches like Petrie’s viewed as if they were representations of observed reality. Well into the twentieth century mummy unwrappings invariably commented on features that might indicate the body’s race, and the heads and skulls of ancient Egyptian bodies were posed in profile, using the powerful trope instituted by Camper and further developed in nineteenth-century anthropometric recording techniques, for instance on ethnographic expeditions and in criminology. In 1925 the head of king Tutankhamun, detached from his body to help remove the gold mask, was propped on a wooden plank to take profile photographs, for instance. Today, the technology of CT-scans and three-dimensional imaging allows similar investigations to take place without physically unwrapping the body, or by revisiting bodies like Tutankhamun’s. In 2005 CT-scans of the king’s head were given to three separate teams in the United States, France and Egypt to allow them to reconstruct his appearance.7 Only the French team were told whose body it was and it was their reconstruction – cappuccino-coloured skin, slender nose, nice eyeliner – that was splashed across the press. Some commentators saw it as not African enough; a few noticed how different it looked to the less visually arresting reconstructions by the other two teams, who did not know the scans were from the body of the famous pharaoh.

Reconstructions of ancient Egyptian bodies always raise debates around race: for all that such reconstructions appear irrefutable, they involve a degree of interpretation and estimation, especially for those features, such as nose contours, lip size and shape, and skin colour, most often taken as physical markers of race. Reading ‘race’ from Egyptian mummies is problematic for many reasons. In any case, the fact that mummification was the preserve of such a small elite means that mummies can only provide limited evidence about the ancient population as a whole – and even within that restricted data set there is tremendous diversity, as we should expect. Rather than ask what ‘race’ the ancient Egyptians were, perhaps the more interesting question to ask is what the racial identities attributed to ancient Egypt allow different people to remember in different ways.

During the nineteenth century America looked to the civilizations of Greece, Rome and Egypt to find the oldest historical models on which to base its experimental form of nationhood. Hence the number of American cities named after Greek, Roman and Egyptian sites, from Athens, Ohio, to Memphis, Tennessee.8 Egypt’s great age and endurance lent gravity to newly founded settlements. Ancient Egypt was not too alien or exotic in this context, nor did it have to be seen, as Types of Mankind had it, as a civilization built on slavery. In fact, Egypt had a double meaning as the place where freedom from slavery could be gained, since the Bible recounted the exodus of Hebrew slaves from their years of imprisonment there. As the African American spiritual ‘Go down, Moses’ recalled:

Go down, Moses

Way down in Egypt Land.

Tell old Pharaoh,

Let my people go.

Ancient Egypt could thus be a source of identification and pride among both African Americans and white anti-slavery activists. But because of its dual associations – as a great civilization as well as an oppressive one, as a place of freedom as well as enslavement, as a place that was African as well as Middle Eastern or Mediterranean – ancient Egypt proved to be an unstable concept. That is, it made for a powerful symbol in a range of contexts, but its symbolic effectiveness stood on shaky ground. Ancient Greece seemed like a solid idea in comparison, and remains so today, not because our ideas about ancient Greece are any more ‘accurate’ than our ideas about ancient Egypt, but because they come with less (or different) cultural baggage attached.

African Americans living with the reality of slavery and its aftermaths were sensitive to these two Egypts: the land of slavery and the land of freedom. Sojourner Truth, herself a freed slave who helped others make the journey north, declared that she had left ‘Egypt’ behind her, while the African American abolitionists Henry Highland Garnet and Frederick Douglass (both also born into slavery) saw Egypt in a positive light, believing it to have been founded by the biblical Ham, son of Abraham, conventionally identified as black. The African American physician and historian Martin Robison Delany held a similar view of Egypt and advocated that his fellow black Americans – men only, of course – should embrace Freemasonry, which had a tradition of black lodges in America going back to the eighteenth century.9 Long after the Civil War ended, African Americans faced deep prejudice and injustice, not only in southern states, where the lynching of black men was a violent expression of white prejudice into the 1960s, but in the north, where economic hardships, restricted opportunities and de facto segregation blighted day-to-day life for many blacks. Having social institutions (a Freemasons’ lodge, a church) and cultural memories (ancient Egypt, independent Ethiopia) that embraced an African identity was a way to foster cohesion and pride in the face of a dominant, Eurocentric society.

Nor was identification with an African past (and present) only a concern in the United States. By the turn of the twentieth century African diasporas around the world, and especially in the former slave-owning countries of the West Indies and South America, sought solidarity with each other and with parts of Africa exploited by imperialism after the 1884 Berlin Conference of European powers set off the so-called ‘scramble for Africa’. In 1900 the first Pan-African Conference met in London, bringing together delegates from the USA, Britain, the Caribbean and Ethiopia, which was one of only two self-governing nations in Africa at the time (the other was Liberia). The delegates petitioned for reforms that would restore dignity to colonies in Africa, concerns that were captured in a resounding address by delegate W.E.B. Du Bois, a leading African American intellectual. Although an international Pan-African meeting would not be held again until after the First World War, the phrase and the concept of Pan-Africanism were firmly lodged in cultural consciousness, and Egypt and Ethiopia were often held up as admired examples of African accomplishments. As Du Bois wrote in his classic The Souls of Black Folk, published in 1903, ‘The shadow of a mighty Negro past flits through the tale of Ethiopia the Shadowy and of Egypt the Sphinx.’10 If all Africans and people of African descent could unite through African-ness, they could more effectively organize and improve their conditions at home. Membership of any large, disparate group – like a nation – depends on imagining a shared sense of purpose, identity and origin. Ancient Egypt readily offered a symbol for Pan-Africanism, arguably all the more potent because it had been misappropriated by whites.

In the United States artists, writers and performers picked up on Pan-African ideals as they sought ways to give a voice, or a vision, to African American experiences. In the 1920s and 1930s a loose collection of cultural figures became known as the Harlem Renaissance, named after a New York City neighbourhood, although the movement was in fact widespread.11 Several of these artists and writers held up the achievements of ancient Egypt as a model for contemporary African Americans. The Harlem Renaissance was a Modernist movement, with many links to artists and writers in Europe who were also, in their own ways, looking to Africa and ancient civilizations for inspiration.

Meta Warrick Fuller, Ethiopia Awakening, 1914, bronze sculpture. |

Lois Mailou Jones, The Ascent of Ethiopia, oil on canvas, 1932.

Aaron Douglas, Meta Warrick Fuller and Lois Mailou Jones were three Harlem Renaissance artists who used ancient Egyptian motifs in their work. Warrick Fuller, a friend of Du Bois and protégée of Auguste Rodin, exhibited a bronze known as Ethiopia or Ethiopia Awakening at The Armory in New York in 1921.12 The exhibition, called America’s Making’, emphasized America’s ‘melting-pot’ pluralism, and Du Bois helped design the section that would represent the heritage and contributions of African Americans. In a booth adorned with the Great Pyramid and sphinx at Giza, Ethiopia represented the emancipation not only of slaves in America, but of the entire ‘Negro race’, in the terms of the day. Warrick Fuller’s statue shows an African woman in the nemes-headscarf of an Egyptian pharaoh, emerging into life from the mummy wrappings that bind her legs. The choice of Ethiopia, rather than Egypt, as the name of the work reflects the close relationship between the two as mythic ideals of Africa, both with ancient histories (‘Ethiopia’ was what Greek and Roman writers termed sub-Saharan Africa) and both with impressive associations. As a Christian country, Ethiopia complemented the pagan gods of ancient Egypt, and in the 1920s Ethiopia also held an appeal because of its imperial identity: its regent at the time was Ras Tafari, crowned emperor in 1930 as Haile Selassie, ‘The Power of the Trinity’.

Lois Mailou Jones similarly used Ethiopia, rather than Egypt, in the title of her Egyptian-themed The Ascent of Ethiopia, an oil painting from 1932.13 The profile head and shoulders of a darkskinned Egyptian queen or goddess dominate the lower right of the canvas, while a celestial body – sun, moon and star at once – beams from top left onto figures of Africans rising past the pyramids and climbing steps towards skyscrapers above the queen’s head. Around the illuminated towers, concentric circles representing art, music and drama capture the spirit of the Harlem Renaissance. Jones acknowledged her debt to Meta Warrick Fuller: ‘Ethiopia’ in her painting’s name consciously echoed Warrick Fuller’s sculpture, although it was recognizably ancient Egypt that provided the visual theme in both works.

Ancient Egypt was one of many lost homelands denied to the descendants of American slavery by the cruel circumstances under which their ancestors reached the New World, and for all that Egypt could offer inspiration for the future, it was also a place of mournful memory. The best-known poet and writer of the Harlem Renaissance was Langston Hughes, whose 1920 poem ‘The Negro Speaks of Rivers’ evokes these lost homelands, from the lands of the Bible, through Africa, to the United States. In the poem’s phrase, ‘rivers ancient as the world’ have been part of black (‘Negro’) history: the Euphrates in Iraq, the Congo in West Africa, the Mississippi that joins the American North and South, and of course the Nile with its pyramids built by the poem’s nameless narrator. With this evocative imagery, Hughes places black experience at the heart of Western civilization. It cannot be overlooked or excised – and like a river, it has a powerful current and runs long and deep.

Egypt as an African homeland spoke to African Americans in the decades after the abolition of slavery in the United States, especially in the ‘jazz age’ of the 1920s, when the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb added to the lustre and lure of ancient Egyptian civilization. After the upheavals of the Second World War, when African countries began to gain independence from colonial powers like France and Britain, they too looked to the continent’s history to forge new identities. The former Rhodesia, for instance, took its new name from the archaeological site of Great Zimbabwe, while former French colonies, like Senegal, took inspiration from Négritude, a Francophone intellectual movement with origins in the 1920s, promoting black accomplishments and opposing colonialism. Like the Harlem Renaissance, Négritude was indebted to Pan-African ideas, but different movements and their adherents formulated and used these ideas in distinctive ways, especially in the post-war political climate.

In the 1950s and 1960s a respected physicist, historian and sometime politician in Senegal, Cheikh Anta Diop, published several influential works emphasizing the cultural unity of Africa. Diop’s approach was resolutely Pan-African: he saw all indigenous Africans as a homogeneous race with social, political and linguistic traits that remained fixed over millennia, as far back as ancient Egypt. Coming of age as he did in the closing decades of French colonialism – and having himself studied in France – seems to have drawn Diop towards a racialized way of thinking, as if the problems facing Senegal and other emerging African nations were literally black and white. Unlike the Négritude movement, which celebrated contemporary African cultural expressions, and in which Senegal’s first president Leopold Senghor was a leading figure, the approach taken by Diop stressed deep-rooted historical factors and innate racial traits that made Africans more enlightened, more cultivated and fundamentally different than the Europeans who had oppressed and exploited them for so long. Diop sometimes used evidence that was selective, or tenuous, to make his arguments, for instance using phonetic similarities between unrelated languages like Wolof and ancient Egyptian to conclude that Senegalese people descended from ancient Egyptians who had migrated to West Africa.14 Bolstered by Diop’s high personal profile, especially after he entered politics, his views reached a wide audience. They struck a chord with some Senegalese, as they continue to do today. Origin myths based on migration feature in several West African countries, some perhaps ways of remembering – or rather, forgetting – the displacements forced on West and Central Africans by the transatlantic slave trade. That ancient Egyptians had once settled along the Senegal river was a less painful cultural memory to incorporate into the new nation’s consciousness.

In 1974 two of Diop’s earlier books were combined to produce an English translation, The African Origin of Civilization: Myth or Reality. Its publication extended the influence of Diop’s work to the Anglophone world and especially the United States, where his ideas chimed with a range of black power movements that had emerged from the civil rights movement. As we saw earlier in this chapter, African Americans already had a long history of identifying with ancient Egypt, though this was by no means straightforward or universal. Still, several U.S.-based historians of African descent had written revisionist accounts of ancient Egypt’s contribution to world history, for instance asserting that ancient Egyptians were the originators of ancient Greek philosophy or, in echoes of Diop, that ancient Egyptians and other black Africans had sailed to the new world before Columbus. The publication of The African Origin of Civilization helped coalesce these varied trends into a school of thought known as Afrocentrism. In the 1980s the author and activist Molefi Kete Asante articulated the Afrocentric project as an overdue shift from Eurocentric views of history and civilization.15 Asante identified the ancient Egyptians as black and promoted the use of the ancient word ‘Kemet’, meaning ‘the black land’, for the ancient Egyptian civilization. Blackness mattered: it was a form of identity with which African Americans were confronted every day, and extending black identity through time and space offered a way to prioritize African contributions that had been ignored, overlooked or written out of history altogether.

Afrocentrism proved to be a broad school of thought, encompassing a range of ideas and approaches. Although it has its own conferences, university programmes and published outputs, Afrocentrism is more than an academic theory or methodology. It has informed education provision in many schools and museums, for instance, where staff cite its value in promoting a sense of personal pride and achievement among disadvantaged pupils with African American or other non-white backgrounds. At one extreme, some Afrocentric ideas drift into ideology, reiterating essentialist, invidious and, in some cases, anti-Semitic notions of race that mirror, rather than challenge, racist ideologies like white supremacism. But as a way to draw much-needed attention to the rich histories of the African continent, and to the reasons why these histories have not been told, Afrocentrism has also proved to be a powerful and positive voice, with ancient Egypt one of the key platforms for articulating its themes.

Afrocentrism garnered national attention in the United States in 1987 with the publication of the first volume of (white) historian Martin Bernal’s Black Athena: The Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilization.16 The grandson of the British Egyptologist Alan Gardiner, who had played a small role in the initial work on Tutankhamun’s tomb, Bernal was a specialist in Chinese history who initially undertook the research for Black Athena as a sideline. The book was an unapologetically academic tome that eventually ran to three volumes, but it had a passionate – some would say, polemical – thesis at its heart. Bernal started from the premise that European scholarship on ancient Greek civilization had its roots in the eighteenth-century Enlightenment and its flowering in the racialized atmosphere of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This is now not as controversial a premise perhaps (it should sound familiar from this book), but at the time studies of classical antiquity had done little to question explicitly what impact this might have had on the formation of the discipline. Bernal argued that bias, especially in German-speaking academia, had led earlier scholars to downplay significant connections and influences that flowed both from the ancient Semitic-speaking world of southwest Asia (the Levant, Syria, Iraq and southeastern Turkey) and from ancient Egypt to early Greek civilization, which, after all, was made up of seafaring societies that traded all around the eastern Mediterranean and beyond. It was his publisher, Bernal later stated, that encouraged the evocative book title Black Athena, which reduced his complex arguments to a re-branding of classical Greece – that cherished font of European civilization – as ‘black’.

Bernal did not identify himself as Afrocentrist, but some Afrocentric scholars and activists embraced him as one of their own. Here was an establishment figure, and a white academic at that, garnering attention and lending support to ideas that seemed broadly similar, although the fact that it took a white scholar’s work to bring Afrocentrism to mainstream attention speaks volumes. Bernal rejected racial classification on the same grounds any conventional Egyptologist would do today, namely that ‘race’ is a historical and cultural construct, not a biological reality. As reaction to Black Athena proved, though, that was not the point: race matters where the study of ancient Egypt was concerned because race matters in our own society.

Classicists, archaeologists and Egyptologists identified many holes in the evidence Bernal used and pointed out that his general idea about cross-cultural exchanges in the ancient Mediterranean was much more widely accepted than he implied. There had been no conspiracy to downgrade African and Middle Eastern contributions to the specific cultural forms that developed on the Greek mainland, the islands and around the Black Sea. But it is true that over the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries Europe’s own myth-making about its origins had driven a wedge between the northern and southern shores of the Mediterranean Sea, a division amplified by the nation-building efforts of Greece and other countries, including Germany. No form of knowledge is pure and infallible, untainted by the circumstances in which it is produced. That holds for classical or Egyptological scholarship produced in Fascist Germany as much as it does for Afrocentric scholarship produced in riot-torn 1990s Los Angeles. Even among the most diligent academics, what constitutes knowledge, evidence and sound argumentation can take many forms, and as soon as we expand these questions of epistemology – the science of knowledge – beyond academia, it is clear that one group’s consensus is another’s glaring fallacy. Where the concept of cultural memory can help is by reminding us that such controversies usually signal that other issues are at stake. Whether ancient Egypt was black or white, African or European, impinges on the cultural memory of ‘our’ lost civilization – and depends on who that ‘our’ includes.

From the 1980s to the present day the American artist Fred Wilson has created a number of museum interventions and works of art that draw attention to suppressed cultural memories, such as American slavery (the artist is himself of African descent). For the 1992 Cairo Biennale, Wilson looked to ancient Egypt and its legacies for an installation he entitled Re:Claiming Egypt. He combined casts and other replicas of ancient Egyptian art with everyday objects like souvenirs, books and clothing, all of which presented ancient Egypt as a black African culture. Wilson was not necessarily promoting an Afrocentric view of ancient Egyptian culture, but rather drawing attention to the debate and the reasons behind it, such as the black/white dichotomy inherited from nineteenth-century race science. In one work, Grey Area, he lined up five plaster casts of the bust of Nefertiti (she of Rihanna’s side tattoo), which he had painted in shades ranging from black to white. For another version of the piece (Grey Area, Brown Version), now in the Brooklyn Museum of Art, Wilson used shades of ‘skin’ tone to paint the plaster busts instead, running like a cosmetic foundation chart from pale ivory to dark chocolate.

By usurping this iconic artwork, Wilson confronts viewers with the assumptions that each of us makes about skin colour, identity and heritage – while his title, Grey Area, seems to admit that uncertainty and unknowability are built into our encounter with the ancient past. That past is only available to us through its material remains and our own imaginations, with the caveat that how we imagine it may depend on who we are. More interesting than arguing for a right or a wrong way to visualize ancient Egypt is reflecting on what different visualizations say about the individuals and societies that produce them, whether that is Rupert Murdoch and his ‘white’ Egyptians, or the Egyptian football players who made ‘walk like an Egyptian’ arm gestures during their 2008 African Cup of Nations victory in Ghana – national pride expressed within an African sporting context.17 Ideas of heritage have become intrinsically tied up with what is often called the politics of recognition or, disparagingly, identity politics. Yet public assertions of European mastery over Egypt, such as obelisks erected in capital cities, are rarely critiqued for accuracy or fairness, the way that African and diaspora identifications with ancient Egypt have been in mainstream Western media. Moreover, amid the competing claims to an ancient Egypt that is white or black, European or African, what is often overlooked, dismissed or ignored is the way that modern Egyptians have sought their own identity in ancient Egypt in the course of the nineteenth, twentieth and now twenty-first centuries.

Fred Wilson, Grey Area (Black Version), painted plaster, 1993.