THE surveyors came first. It was fitting, since they enjoyed life in the open more than most men. They were like the early-nineteenth-century mountain men, adventurous, capable of taking care of themselves, ready for whatever the wilderness threw at them. They were out in front of civilization, enjoying the views, the air, the campfire, the game cooked over it, drinking pure water from the rivers, creeks, and lakes, exploring the country, mapping it. For the surveyors it was pure joy.

Nothing could be done until they had laid out and marked the line. On flat ground, with no trees, the work involved in surveying was relatively easy, but there is precious little terrain on earth that has no ridges, bumps, ravines, or watercourses. Because a nineteenth-century train could not run up or down an incline of much more than 2 percent or go around a sharp curve, the hills or ridges had to be cut through to keep the tracks close to or at the level. The ravines had to be filled for the same purpose, or else a bridge had to be strung across them. In foothills, not to mention mountainous country, the task was far more difficult.

The surveyors who went first—Dodge, Dey, or Judah—were spared the task of laying out the exact line for the graders to follow, but they had to pick a general course that would work. They had to find passes through the mountains that could be reached from the ridges that kept below a 2 percent grade. They wanted to avoid major lakes and rivers. At stream crossings, they were looking for places that could be bridged without undue difficulty. They hoped to hold the cuts and fills down to a minimum. They hoped to avoid major snowstorms that would fill the road and prevent train passage. In open, relatively flat country, they wanted to be next to or near streams, or at a place where water could be dug, since the steam engines required water to operate, as did the workers, men, and animals. Staying as far away as possible from Indians was another goal, but staying near buffalo and other animals was desirable. Most of all, the CP wanted to find a route that was as straight as possible to the east, while the UP wanted to go straight west.

The surveyors had nearly two thousand miles to cover, over every kind of terrain. They had no airplanes to provide them with a view from above. There were no helicopters, and no balloons. And for nearly the whole of the route, there were no maps. There was almost nothing to indicate settlements, for other than Salt Lake City, there were none of any size and only a few hamlets. Nor were there any topographical maps. They had nothing to indicate lakes or rivers, or the shape of the mountains over or around which the railroad would pass. Like Lewis and Clark and other explorers, they had only a vague idea of what lay ahead.

Despite their handicaps, the original surveyors and the ones who followed to mark out the line for the graders did a grand job. Nearly a full century later, in the 1950s and 1960s, when the surveyors flying in airplanes and helicopters and equipped with modern implements and maps laid out a line for Interstate 80, they followed almost exactly the route laid out by the original surveyors. Travelers in the twenty-first century driving on 1-80 are nearly always in sight of the original tracks.

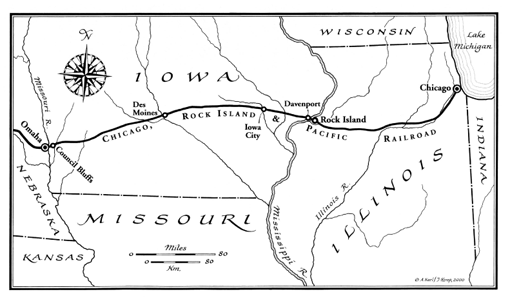

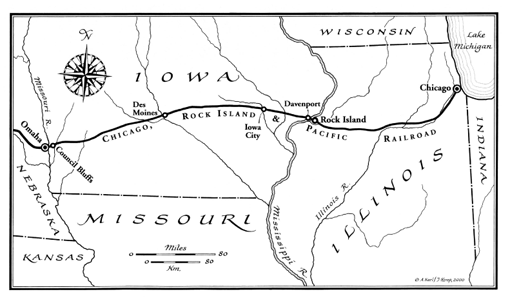

THE story of Theodore Judah’s initial examination for the Central Pacific and his report on crossing the Sierra Nevada has already been told. For the Union Pacific, Grenville Dodge was the first man—he recommended following the Platte River to the base of the Rocky Mountains—and Peter Dey was the second. On September 6, 1862, only four days after the initial meeting of the directors of the Union Pacific in Chicago, they instructed Dey to examine and report to them “the passes between the one hundredth and the one hundred and twelfth parallels of longitude.”

Dey examined three routes west of Julesburg, Colorado. The first followed the valley of Lodgepole Creek coming out of the Black Hills, then went up and over the Black Hills through Cheyenne Pass and down to the Laramie Plains, The second followed the North Fork of the Platte River through western Nebraska, went over the Continental Divide via the relatively easy crossing called South Pass, then west to the Green River in western Wyoming. The third followed the South Platte River to Denver and then led up the Rockies to cross the Continental Divide at Berthoud Pass.

Dey concluded that the North Fork line would be much too long and dangerous, and going across Berthoud Pass would be beyond the capacity of nineteenth-century track builders and locomotives. Although the Denver newspapers, politicians, and businessmen wanted the tracks to come through the city, Dey was right. In fact, there was no railroad over Berthoud Pass until 1926, Dey picked the route over Cheyenne Pass (later called Lone Tree Pass, then Evans Pass, then Sherman Pass, ultimately changed to Sherman Summit and finally Sherman Hill), On November 4, 1864, Lincoln approved Dey’s route.

Brigham Young also wanted the tracks to run through his city. And he was, with Durant’s help, a member of the UP board of directors. On October 23, 1863, Young wrote to Durant saying that he had engineers ready to lay out a route through the Weber River Canyon down to Salt Lake City, In January 1864, he asked when Durant wanted him to begin work, promised workers to make the grade and lay the tracks, and reminded Durant that in the Weber Canyon there were “extensive coal beds,” He concluded that he was “in readiness to aid in completing a work of such magnitude and usefulness as the Pacific Railroad,”1

Young’s eagerness and the potentially lucrative coal deposits notwithstanding, what was needed most of all, at least at first, was a line through the Wasatch Range into the Salt Lake Valley, Accordingly, Dey recruited two fine engineers, Samuel B. Reed and James A. Evans, to head separate parties to find a passage. On April 25, 1864, Dey wrote to Reed instructing him to run a line from Salt Lake City up to where the Weber River broke through the mountains, then east up the Weber Canyon to Echo Creek, and then on to Wyoming. Dey wanted Reed and Evans to examine other routes, but he thought the Weber-Echo would be best, although he admitted “that is rugged country and there is not enough known of that region to give you more than a general outline,” Dey concluded, “As a general rule it will be safe to sacrifice distance and straight lines to cost of construction, the aim of the company being to secure a line they can afford to build.”2 That last admonition remained to be seen.

• • •

REED headed west in April 1864, first by train to the end of track at Grinnell, Iowa, then by stagecoach to Omaha. It was an excruciating ride. In Omaha there was a rush of gold seekers trying to get to the latest discovery, in Montana. “Hundreds pass through here every day,” Reed wrote, “old men, young men, the lame and the blind with women and children all going westward seeking the promised land.” The stage ride to Salt Lake City consumed thirteen days, and he was more than glad to get there, for “I have never been in a town of this size in the United States where everything is kept in such perfect order. No hogs or cattle are ah lowed to run at large in the streets and every available nook of ground is made to bring forth fruit, vegetables or flowers for man’s use.”3

Reed met with Brigham Young, who gave him equipment and fifteen men. After training them, Reed headed north to where the Weber River emerged from the Wasatch Range onto the valley. He went up the canyon until he came to Devil’s Gate, “the wildest place you can imagine.” After further progress upstream, he came to Echo Creek and followed it across the mountains to Bear River, north of the Uinta Mountains and near present-day Evanston, Wyoming. From there it was almost straight east to Omaha.

The exploration took Reed four months. He never enjoyed work so much. The brilliance of the air, the warm days and cold nights, the beauty of the scene, and the idea that he was the advance agent in transforming this land from nature’s wilderness to civilization, all transformed him.4 From August to November, he did more surveying, looking for a route south of the Weber River, then for one leading west from Salt Lake City, and finding neither. He returned to Omaha by stage. It was a bone-rattling trip, twenty days and nights of blizzards that, he moaned, “almost froze the life blood out of me.”5 He could only hope that 1865 would be better. Another surveyor was Ogden Edwards. His assistant, Hezekiah Bissell, called him “the hardest drinker I ever saw. His regular drink was two pony glasses of straight whiskey.” Yet Edwards was a highly regarded surveyor.6

DOC Durant was a man heartily disliked. He had few redeeming qualities to overcome his arrogance, bluster, quick and often wrong judgments, bossiness, show-business attributes, and lack of common sense. Yet he did well, sometimes, in picking out the men he wanted in charge of building the UP, especially the man at the top. All through the Civil War, he had kept asking Grenville Dodge to be his chief engineer. On that one he was exactly right. His problem was getting Dodge to accept.

There was no chance of it so long as the war went on. Nor so long as the Native Americans of the Plains were burning, looting, raping, and robbing the American settlers in their homesteads or villages. Grant had appointed Dodge to command the Department of the Missouri, comprising all the land between the Missouri River and the Rocky Mountains. On January 15, 1865, Lincoln sent Dodge a telegram ordering him to pay special attention to Missouri, whose citizens were badly divided between North and South; he was needed to keep the peace.

But both Dodge and Grant believed that Dodge’s main task was to curb the Indians, who had done great damage. On January 7, 1865, Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho rode into Julesburg, Colorado, killed fifteen soldiers and a number of civilians, and burned every building. Farms along the Platte River were also burned to the ground. Among those killed was Lieutenant Casper Collins, for whom Casper, Wyoming, is named. Dodge wrote that Collins was found “horribly mutilated; his hands and feet were cut off and his heart torn out. He was scalped and had over 100 arrows in him.”7 After witnessing one Native American meeting, the wandering British reporter Henry Morton Stanley put it succinctly: “The Indian chiefs were asking the impossible. The half of a continent [they wanted] could not be kept as a buffalo pasture and hunting ground.”8

In 1865, Dodge moved his headquarters out of St. Louis to Fort Leavenworth, on the Missouri River in Kansas. It was cold. The thermometer dipped below zero almost nightly, and sometimes to as low as thirty below just before dawn. To meet the Indian threat, Dodge sent out a general order to all district commanders on the Great Plains: “Place every mounted man in your command on the South Platte route; repair telegraph lines, attack all bodies of hostile Indians large or small; stay with them and pound them until they move north of the Platte or south of the Arkansas [River]. I am coming with two regiments of cavalry to the Platte line and will open and protect it.”9 In so doing, Dodge was carrying out his specific injunction from Grant, “to remove all trespassers [Indians] on land of the Union Pacific Railroad.”10 He toured the country and had every soldier on the Platte in the saddle instead of by a fire in the stockades. Shortly, the general manager of the Overland Telegraph notified Washington that telegraphic communication had been resumed from the Missouri River to California.

Grant wired him a query: “Where is Dodge?”

The manager telegraphed back, “Nobody knows where he is but everybody knows where he has been.”11

DODGE was not employed by the Union Pacific and he had not seen Dey’s report to the directors recommending the route up Lodgepole Creek. His job was to look for Indians making depredations on white settlers, but he was also looking for a route over the Black Hills. If he was looking for himself, to make something for himself out of his exertions, then so be it. If he was looking for his country, so much the better. If he was looking for his superior—William T Sherman, who in 1865 had been made commanding officer of the Military Division of the Mississippi, embracing the land lying between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains—then he was doing exactly what his superior wanted.

As Sherman took up his new duties, he recorded in his Memoirs, “My thoughts and feelings at once reverted to the construction of the great Pacific Railway, which was then in progress. I put myself in communication with the parties engaged in the work, visiting them in person, and assured them that I would afford them all possible assistance and encouragement.” Not that he had all that much faith. When he heard the politicians talk of throwing a railroad line across the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains, Sherman said, he was at first “disposed to treat it jocularly.”12

DODGE’S campaigning, although critical to the UP, met with strong objections from Durant and his fellow directors. Durant wired Dodge reminding him that he had promised to become the railroad’s chief engineer upon the expiration of the war. The directors offered him $10,000 a year and stock in the Crédit Mobilier to resign from the army and begin work at once. In his reply, Dodge pointed out the obvious: no railroad could be built across the Plains until the Indians had been subdued.

General Sherman, meanwhile, had come to realize the correlation of the Indian campaigns and the task of the chief engineer of the UP. He backed Dodge in everything he did and communicated his belief to the UP directors. No one in the United States was then ready to do battle with William T. Sherman. The directors therefore telegraphed word to Dodge that the position of the chief engineer would be held open for him until he had completed his campaign against the Indians.13

ASIDE from lines marked by surveyors and Dodge, what the UP needed most was money. President Lincoln was once again there to help out. On January 20, 1865, the President called Congressman Oakes Ames into his office. Lincoln called him “the broad shouldered Ames.” Ames arrived immediately after dinner and stayed until well after midnight. The two men talked about the UP. “Ames, you take hold of this,” Lincoln said. “If the subsidies provided are not enough to build the road, ask double, and you shall have it. The road must be built, and you are the man to do it. Take hold of it yourself. By building the Union Pacific, you will become the remembered man of your generation.”14 Ames, glad to have Lincoln appeal to him, began putting money and his political clout into the enterprise. He and his brother Oliver bought $1 million worth of Crédit Mobilier stock, and he loaned the UP $600,000.15

It certainly needed it. Durant ordered the railroad built with the oxbow south of Omaha as an integral part of it, which would bring in more government money and lands—when built.* Meanwhile, the fight over the oxbow had cost the UP almost $500,000 and even more in good will. The Chicago Tribune called the oxbow an “outrage” perpetrated by “a set of unprincipled swindlers” intent on “building the road at the largest possible expense to the Government and the least possible expense to themselves.”16

Be that as it may, Durant had other problems. Engineer Samuel Reed reported that his surveys were “extremely difficult and dangerous” because of the “hostility of the Indians everywhere. Until they are exterminated, or so far reduced in numbers as to make their power contemptible, no safety will be found in that vast district extending from Fort Kearney to the mountains, and beyond.”17

In addition to laying out the route, Durant faced a logistical nightmare. To get building materials to Omaha required shipping them up the Missouri River from St. Joseph, Missouri, 175 winding miles on a river that was navigable by steamboat only for three or four months per year. The only wood available in the area for ties was cottonwood, which was so wet that it could last but two or three years, and the UP needed twenty-five hundred ties for each mile. Laborers were hard to get, so hard that Dodge offered captive Indians for the grading. Irishmen had been contracted in New York, and they worked hard, but they also played hard and were likely to strike when they were not paid.

IN April 1865, as the Civil War came to an end, Lincoln was shot and killed. The sadness of Lincoln’s death was somewhat compensated for by the end of the war. Though the best and most powerful friend the transcontinental railroads ever had was gone, for Durant and the UP, the first thing that meant was thousands of unemployed young men from the Union and Confederate armies. For both the CP and the UP, it meant the unleashing of great quantities of money. With almost explosive force the industrial, financial, and transportation systems of the North were let loose. The United States began to take its place as a world power.

The Gilded Age was about to begin, but before America could industrialize, it needed a transportation system. On July 22, 1865, Harper’s Weekly ran an article on “Railroads in Peace-Time” that summed up what had been accomplished and predicted what was to come. “From 1859 to 1864 the business of the roads had more than doubled,” it opened. And in June 1865, “Traffic returns show an average increase over last year of 30 to 40 per cent—far in excess of those of the most active period of the war.” The magazine said, “This is an astounding fact, one for which not one among the best-informed railroad men or Wall Street financiers was prepared.” In fact, they had all predicted that the end of the war would mean a sharp downturn in railroad traffic. The article went on to state, “Our roads, at best, are only half built. They only cost, on the average, $40,000 a mile,” whereas the British roads cost $170,000 per mile, the French roads $101,000.

For the United States, there was no limit that the magazine could see.18 The future for the railroads looked especially bright to the west of the Missouri River and east of the Sierra Nevada, where the government owned nearly all of the land and would give much of it away to the railroads.

THE surveyors were critical to making it happen. For the UP, although the general route north of the Platte River had been set, the exact line had not. Meanwhile, with all his worry about labor and ties and rails and locomotives and money and more, Durant and the UP managed to spike not one rail until July 1865.

Still, the corporation had surveyors working out in front. Among them was Arthur Ferguson, one of four sons of the first chief justice of the territorial Supreme Court of Nebraska and one of the early congressmen from the state. Arthur was reading law, preparatory to taking his bar exam (he graduated from the University of Iowa with the degree of LL.B. in 1870). Between 1865 and 1869, he worked spring, summer, fall, and on one occasion through the winter for the UP as rodman and assistant engineer. He kept a journal, sometimes missing a day or more, sometimes months, but often writing in rich detail. He is described as a long-faced, rather solemn-looking man, but he kept a fine journal.19

In the summer of 1865, the twenty-four-year-old Ferguson went to work as a surveyor for the civil engineers who were locating the track from the mouth of the Loup River, at the village of Columbus, Nebraska, along the north side of the Platte River for 150 miles west. Previous surveyors had already marked the line from Omaha to Columbus. Ferguson’s party consisted of fifteen men, including assistants, teamsters, and cooks, carried by several covered wagons drawn by horses and mules. They slept on buffalo robes in five white duck wall tents. They got up early, traveled all day, and pitched their tents around a central campfire.

Immediately after a breakfast of meat, bread, potatoes, and strong coffee, the teams were hitched and “we were all rolling over the prairie westward.” Very occasionally they saw a cabin or a few acres of sod-breaking by some hardy pioneer. By noon of the second day, they were at the banks of the Elkhorn River, “one of the most crooked and winding streams I ever saw.” It would run nearly a mile to make a gain of only a few hundred feet. The banks were fringed with beautiful grasses and flowers. The river ran sixty feet below the banks. “Before us was spread a vast plain as far as the eye could reach.” As they traveled farther west, they came to Raw Hide Creek, a small muddy stream that took its name from an 1849 event in which a man headed to California for the goldfields was caught by Indians, who proceeded to skin him alive and torture him to death.

On August 2, the party reached Columbus, where it camped for four days in order to provide supplies for the survey, primarily “stake timber” for the line. Thus did one of the principal problems of building a track across the Great Plains present itself: there was no timber for the next two hundred miles or so. The surveyors needed stakes to mark the line.

When the party got going, the wagons hauling the supplies went ahead to make camp along the Platte, while the surveyors with a wagon carrying their instruments, food, and stakes went to the line and started staking it. They worked until noon. After an indifferent lunch packed in their wagon, they started out again, and by nightfall had gone ten miles. By the third day of ten miles per day, the party camped “at the deserted homestead of some settler who had been run off by the savages. Quite a number of whites had been killed some time previous by roaming war parties of Sioux.” But the Indians did not bother the surveyors, who were well armed. The surveyors were usually well north of the Platte River, while the remainder of the party went forward to set up camp. Since the surveyors often worked until dark, the others would make a large camp-fire to guide them in.

Each day, the surveyors followed the route laid down by Dodge, Dey, Reed, or Evans. They used the wooden spikes to leave a message for the graders—here is the exact line. Sometimes it was flat; sometimes it crossed ridges that would have to be cut; sometimes there were drainage ditches that must be filled, or occasional creeks that must be bridged. Sometimes the surveyors found a way to go around ditches or ridges, which saved time and money even though curves would have to be built to accommodate the track. Such devices of economy explain why today the old track bed seems to wander whereas the replacement laid out in the twentieth century runs in a straighter line.

DODGE was determined that the UP be built just as soon as he could bring peace to the Great Plains. In September 1865, while returning from the Powder River campaign in today’s Wyoming, he set out to discover a pass over the Black Hills (today’s Laramie Mountains). He wasn’t hopeful, because of the short slopes and great height of the hills on the eastern side, but he never overlooked anything. Striking Lodgepole Creek on the first day of fall, Dodge took six mounted men with him to explore up the creek (which eventually discharged itself into the South Platte River, near Julesburg). When he got to the summit of Cheyenne Pass, he headed south along the crest of the mountains to get a good view of the country. His other troops were meanwhile passing south down the east base of the Black Hills. He was on the divide of the hills (not the Continental Divide, which is to the west, near present-day Rawlins). It was a most beautiful spot, with meadows spreading out, covered with grass and flowers, buttes and outcroppings, ravines, no trees to speak of, with the Medicine Bow Mountains to the west and south and the Laramie Mountains to the north, and the Black Hills surrounding him.

About noon, Dodge and his party and a group of Cheyennes discovered each other.* He gained the high point, then began to signal to his troops at the base of the mountains, meanwhile dismounting and starting down the ridge between Crow Creek and Lodgepole Creek. He kept the Cheyennes at bay by firing at them occasionally. It was nearly night when his troops saw his smoke signal and came to his relief.

In going down the ridge separating the two creeks (Crow Creek flows into today’s Cheyenne, Wyoming, and Lodgepole Creek flows to the city’s north), Dodge wrote, “We followed this ridge out until I discovered it led down to the plains without a break.” He said to his men, “I believe we have found the crossing of the Black Hills.” He marked the place by a lone tree. Dodge’s mentor Dey might have questioned his use of the verb “discovered” in his account, but never mind. Dodge, like Dey, had found the way to go.20

BEHIND the surveyors came the graders. There were a few hundred of them, mainly recruited in New York or other Eastern cities, some immigrants born in Ireland or elsewhere in Europe, some second-generation Americans. They were lured to the West by the promises of steady work and high wages—as much as $2 or even $3 a day, sometimes more. They were mostly young veterans of the Civil War, with little or nothing to go home to. In Nebraska they were organized into teams.

They were commanded by various bosses. The “boarding boss” was at the top—his tent went up first when camp was made. Then came the camp doctor, if there was one—often there was not—whose job was relatively easy, because when the water was good and the food untainted the health of the men was excellent. They lived in the open air, worked hard, ate and slept well. If there was no camp doctor, the boarding boss had a medicine chest filled with bandages and a few simple remedies.

There were various stable bosses who assigned the men to their jobs. Each boss might have one hundred horses and mules working his wagons, but he knew them all by name. The driver and the harness for a team were never changed, and each driver was responsible to the boss, who was expected to turn the outfit back to the contractor at the end of the season in as good shape as when he took it.

Then there were the walking bosses, who had their eyes constantly on the men. They used vigorous profanity and time checks to keep the men working. If a boss caught a man loafing, he cursed at him. The next time, he cursed in a louder voice. The third time, the walking boss called the timekeeper and gave the man his time, adding for the enlightenment of the others, “This is not a Salvation Army, but a grading outfit.”

Occasionally the Irishmen went on strike—whenever Durant failed to forward their pay. When it did not arrive on time, they turned volatile and surly. “What a time we have been having here for the last four weeks,” a weary contractor reported in the summer of 1865, “with Irishmen after their pay, I can assure you it is enough to make men crazy.”21

The men worked with shovels (sold by Ames, of course), picks, wheelbarrows, teams, and scrapers. The younger men were usually the drivers, the older ones did the plowing and filling. The men in their late teenage years or early twenties were generally the shovelers. The job of all was to lay out a grade for the track, one that was level with only a bit of curve, two feet or more above the ground, so it would not be flooded out. Mainly that required digging dirt, filling a wheelbarrow with it, taking it to the grade, and dumping it. Sometimes two men used a dump wagon drawn by a horse.

They dumped the dirt onto the bare ground. First the grass and roots had to be removed and tossed aside—not turned over. The dumping boss was a man with a good eye and an unmistakably Irish accent. He stood on the grade and indicated with his shovel where he wanted the dirt dumped. He leveled the dirt with his shovel, and under his constant care the grade grew with just the proper pitch until the top was leveled off, ready for the crossties. The grade at the top was wide enough for one or two tracks, or twelve feet from “shoulder to shoulder.”

Promptly at noon, the big watch of the walking boss snapped and he called out “Time!” Every man in the outfit heard him, as did the mules and horses. Everything stopped. The animals were unhitched and put to water. Then the men went to the boarding tent, where their appetites made even the coarsest fare taste good, if not delicious. At one o’clock, the shrill voice of the walking boss was heard and the men went back to work—although after the hearty meal it took a vast amount of profanity to get them stepping again.

The bosses, it was widely agreed, were not tyrants. The average grader had muscles like steel and could take care of himself in a rough-and-tumble fight, and anyway the bosses did not resort to pick handles. There were exceptions, but generally they ruled with comparative ease. And they got the grade done.

When the bosses couldn’t level the grade, the scrapers, drawn by oxen or up to four horses, were called in to do the job. When solid rock was encountered in a ridge line, which was seldom in the Great Plains, the men used hand drills and stuffed the hole with black powder. When the rocks blew apart, the remainder of the cut was dug out and leveled. A cut was done entirely by hand. The men would form an endless chain of wheelbarrows. For fills, the dirt was dumped in. The land yielded nothing but some limestone for masonry work. There was no gravel for ballast, so mainly sand was used.

At night, after supper, the men would play cards or sing songs, such as “Poor Paddy he works on the railroad” or “The great Pacific railway for California hail, bring on the locomotive, lay down the iron rail.” Others were “Pat Malloy,” “Whoop Along Liza Jane,” or “I’m a rambling rake of poverty, the son of a gamboleer.” The low notes of the Jew’s harps and harmonicas floated across the cool night air. The songs were sung almost regardless of harmony and in contempt of tune.

By mid-October 1865, the Omaha Weekly Herald reported that the graders were up to the Loup River (Columbus) and advance teams were rapidly making their way across the next hundred miles. Preparations were being made for putting in the foundations of the Loup Fork Bridge, which, at fifteen hundred feet in length, was “a great work in itself” and was scheduled to be erected in the spring of 1866.22 The trestles were being made in Chicago in accordance with measurements and instructions laid out by the surveyors.

BEHIND the graders came the track layers. In 1865, they made only forty miles, just beyond the Elkhorn River, and their story is best saved for later. Meanwhile, the white population of the Great Plains was increasing. Each year about a hundred thousand persons traveled either part or all of the way across the Plains. Many of them became a part of the 10 percent of transfrontier population occupying what the Census Bureau called the “vacant spaces on the density map.” Historian Oscar Winther comments: “They were the hunters, trappers, traders, miners, lumberjacks, soldiers, government agents, and cowmen; they were the vanguards of migrants en route from old to new locations; they were the packers, teamsters, stage and express men, sutlers, travelers, and floaters of all types.” It was estimated that they numbered 250,000 by 1870.23

DURANT’S problem was money. He brought much of it on himself by his extravagance. He had hoped to raise money through a subscription to Crédit Mobilier, but it had fallen flat. Then, with great fanfare, the UP tried a public stock subscription, but Charles Sherman, the general’s brother who was working for the UP, said that the offering failed so utterly that “not a dollar was subscribed.”24 Another director complained to Durant, “You do spend an awful pile of money.” He borrowed money at 19 percent per annum. “We were deeply in debt,” Oakes Ames recalled, “and very much embarrassed, and we were using our credit to the utmost extent in driving the work along.”25

Much of it couldn’t be helped. There was no timber, and only thin groves of Cottonwood, so the immense amounts needed for ties, trestles, buildings, and other purposes had to be shipped up the Missouri River. The UP’s first locomotive, called the General Sherman, had arrived via this route along with two flatcars, with two other locomotives and more flatcars to follow in 1865. The Burnettizer—a machine that treated the cottonwood through a vacuum device that drew out the water in the trees, putting a zinc solution in its place—was also at hand.* Cottonwood made ties that were too soft and perishable, even when Burnettized, but the cost of importing hardwood was prohibitive.

Oakes Ames put in some more of his money and persuaded Cyrus H. McCormick, the inventor of the reaper, and others to buy stock in the Crédit Mobilier. Durant meanwhile drove the work as best he could, which meant primarily by telegraphic orders. He told the contractors to use cottonwood, which when treated would last for three years, long enough for train tracks coming from the east to reach Council Bluffs and thus reduce the cost of hardwood timber ties from Wisconsin. Other telegrams read, “How much track now laid how much do you lay per day?” “Increase your force on ties. Important the track should be laid faster, cant you lay one mile per day.” “What is the matter that you cant lay track faster.” “Run the Burnetizing machine night and day.” “I insist on being fully advised.”26

And so on. What Durant needed was to secure government loans on the track already laid, but the UP got nothing until it had completed acceptable track. Working at a furious pace, the crews managed in 1865 to finish forty miles of road with all the required sidings, station houses, and water stations before the weather laid them off.27

ONE young engineer working for the UP, James Maxwell, who had previously been employed by the Pennsylvania Railroad, was astonished by what he saw in the Platte River Valley: plenty of wild game, along with the excitement of exploring a new country and a little element of danger from hostile Indians to give zest to everything. In a memoir written in 1896, he said, “This was a grass country. On the river bottoms it grew to be over seven feet in height.” Some surveyors said the grass was as much as ten feet high. Maxwell went on, “In riding a buggy a person would have to stand up to see over the top of the grass. In running a line through such grass, he was liable to be lost.” That fall he thought it “very beautiful to see the fires at night, from the various camps, circling around the hills among the short grass, but when the grass in the bottom lands caught fire, it was a grand and appalling sight.” A young surveyor named H. K. Nichols wrote in his diary, “The valley is one of the most fertile I suppose in the states.”28

That fall of 1865, out on the Plains, the young surveyor Ferguson saw unusual sights. Near today’s Grand Island, “for a distance of ten miles the prairie is one vast prairie-dog village. For miles and miles the ground is completely covered with their holes, and on most of them, as far as the eye can reach, you will see them sitting upright on their haunches.” Some of the men shot and ate them, but not Ferguson.

At Fort Kearney, on the south bank of the Platte, there were some four hundred troops in quarters, both infantry and cavalry. At this point four men from the surveyors’ party said they were damned if they would go on, for it was here that the Indian danger became acute and would remain so until the Rocky Mountains. Here too the party received its military escort, a sixty-man company of the Twelfth Missouri Cavalry, which Dodge had just sent to Fort Kearney. “The soldiers were very much dissatisfied at this action,” Ferguson recorded, “and at times were on the point of rebelling against their officers. They said that they had enlisted for the war to fight rebels and not to go out into the western wilderness to fight Indians.” But when the party set out again the following day, half the Twelfth Missouri stayed with the surveyors while the other half stayed with the main party on the river.

Ferguson described the soldiers’ way of making camp. “It is a busy and lively sight,” he wrote, “after the day’s march to see the troopers busily engaged in rubbing down their animals, for whom they have quite an affection, calling them by pet names. Their campfires burn brightly after nightfall and the solemn tread of the sentinel, with bright gleaming carbine, assures us if, in the still hours of night we are attacked, the enemy will receive a warm reception.”

West of Kearney, “the country becomes wilder and more desolate.” The grass grew several feet in the spring and summer but by mid-September was dead. Vast prairie fires illuminated the country at night, vast volumes of black smoke rose up during the day. “The air is full of flying cinders and the smell of burning grass. We come across vast herds of wild game, mostly antelope.” At night the party slept with loaded arms by their sides, additional ammunition cartridges in their hats beside their heads, along with their loaded revolvers.

The soldiers, who spent the day scouting to the north, often returned with antelope, deer, or part of an elk strapped behind their saddles. By October, the Platte was so low it could be forded everywhere, and at times the men would wade out to the small islands to gather in the grapes that grew in wild profusion.

On November 1, the party reached the hundredth meridian (near today’s Cozad, Nebraska), which had been the objective point. The men expected to return to Omaha, the soldiers to Fort Kearney. They were all eager to do so, for the nights were getting much colder. But their leaders held them over to triangulate the Platte. Finally, at daylight on November 10, they received permission to start home. “At the call of the bugle, the soldiers as one man flung themselves into the saddle and commenced the march.”

But in an hour, they saw two individuals approaching them, who turned out to be Jacob House and James A. Evans. House was a UP division engineer, and Evans a surveyor who had, at Dey’s orders, among other things, run the original line along the north bank of the Platte. They announced that they had come to take charge of the party, which was to continue its survey to the south, down to the Republican River. The decision to go on straight west had not yet been reached; the railroad might well bend to the south, then west to Denver. This news came as “a surprise and a great disappointment to us,” Ferguson recorded. Some of the party said they would not go on.

Evans dismounted and told those who refused to continue to step forward three paces. No one dared.

“All right, men,” Evans proclaimed. “Turn about and march back to the old camp.”

The troops joined the railroaders. The soldiers “complained a great deal. They said that in case of an attack they would leave us to ourselves and do nothing towards our defense.”

The next morning was “very cold.” Clouds laden with snow moved in. The men had to cross the Platte River, which was in places up to their armpits and terribly cold. The following day, “we passed the new-made graves of some twelve men who had recently been killed by the savages.” Snow began, and by mid-afternoon “we were in the midst of a furious storm.” The party pitched its tents in a cottonwood grove. “We all had a terrible night of it. The cold was severe and the ground was so damp and wet that it was next to impossible to sleep. The horses were fed with large quantities of cottonwood limbs.”

After two more dismal nights, Ferguson and the men and troopers started for the Republican. “We are now in the midst of the worst Indian country in the entire West,” he wrote. “It is the very stamping ground of the war parties of various tribes.” No wonder. “This is the great buffalo country of the West,” he noted, “and sometimes a black, surging mass can be seen extending in every direction as far as the eye can reach, the herd running up into thousands and thousands.” The soldiers wasted their ammunition by shooting them in sport, “leaving them on the ground for the wolf and the raven.”

Despite an abundance of animal life such as no modern man has ever seen, and only Lewis and Clark and their men and a few other white men had seen before, Ferguson was struck by the scene. “This is a terrible country,” he wrote, “the stillness, wildness and desolation of which is awful. Not a tree to be seen. The stillness too was perfectly awful, not a sign of man to be seen, and it seemed as if the solitude had been eternal.”29

Shortly thereafter, the party returned to Omaha, the soldiers to Fort Kearney. They would start again, from the hundredth meridian, when the weather became fair.

THE 1864 Pacific Railroad Act required the UP to complete the first hundred miles of track by June 27, 1866. Durant had talked confidently of building that amount in 1865, but he didn’t come close. In September 1865, he confessed that the UP would be lucky to complete sixty miles by the end of the year, but he didn’t come close to that either. By December 31, the UP had laid forty miles of track. Because the 1864 bill had reduced the number of miles completed before the bonds would be given out from forty to twenty, that feat meant that, when the government commissioners accepted the UP’s forty miles of track, the railroad would get $640,000 of government bonds ($320,000 per twenty miles, or $16,000 per mile).

In addition, Durant had gathered together in Omaha a set of superb workers who were just waiting for the warm winds of spring before starting out again, either to lay track or to grade or survey. They were tough, hardy, eager. And with the war over, there were thousands of young men, all veterans of either the Union or the Confederate Army, who were looking for work. The UP’s first locomotive had arrived. Further, Durant had faced up to the need for reorganization, on which he expected to get started immediately.

Meanwhile, he was pushing his original surveyors as hard as he could. He had pulled Evans in, but Samuel Reed was still out there, working well beyond the valley of the Great Salt Lake into areas that were a long way away for the UP. Still, Durant wanted to know. In the fall, he had told Reed to find a route from Salt Lake to the Sierra Nevada.

Reed set out, intending to go via the valley of the Humboldt River to the valley of the Truckee, on the California-Nevada border. In November, he wrote to Durant. He was unhappy to report that he had not reached the Truckee, because of lack of water, but he had made a line from Salt Lake to the place where the Humboldt sank into the ground. After that the desert stopped him. Reed reported that he could run a line from the Salt Lake to the valley of the Humboldt “without a cut or fill exceeding 15 feet or grades exceeding 75 feet per mile.”30

That was good news, even though it would be a considerable time before either the UP or the CP could take advantage of it. But the anticipation was running at a fever pitch. The Denver-based Rocky Mountain News spoke for nearly all of America when it stated, “There is one theme everywhere present. The one moral, the one remedy for every evil, social, political, financial and industrial, the one immediate vital need of the entire Republic, is the Pacific Railroad.”31

The editors of the Railroad Record, however, were critical of the way Durant and company were laying the track. “We confess that we are not satisfied,” they wrote. “Neither is the country, which has a right to expect more vigor in its construction.” The sloth and poor-quality construction (for example, sand rather than gravel was being used for ballast), according to the Record, were “an insult to the generosity and magnanimity of the American public.”32

* As it was, but when E. H. Harriman took over the road—which was bankrupt at the time, 1901—he straightened it out, using Dey’s original line.

* Dodge was approximately at a spot on today’s Interstate 80, about twenty-five miles west of the junction of 1-15 and 1-80, at eight thousand feet of altitude, or fifteen feet short of the highest point on the 1-80 system. There is a sign there that points to, alas, geographical features of the countryside rather than Dodge’s adventure.

* The Burnettizer was a huge, one-hundred-by-five-foot cylinder, sent to Omaha by steamship. By 1866, the company had three of them. After the water was drained and the zinc solution put in, the ties were heated and dried. The ties cost 16 cents each to be processed. The UP saved money in building, but spent much more in replacing the cottonwood ties—but by then the railroad was completed. This was in accord with the general principle: Nail it down! Get the thing built! We can fix it up later.