DOC Durant had spent far too much money to get through Nebraska and Wyoming fast, and had promised even more to Brigham Young and the Mormons to beat the CP through Utah. It was not possible for the company to sell enough stocks and bonds, or to collect enough loans in the form of 6 percent bonds from the government, even to come close to paying its due bills. It had no hope of paying off longer-term debts. The company owed around $10 million. Meanwhile, in December 1868, the Crédit Mobilier had paid a huge dividend to its stockholders. It amounted to nearly $3 million, which brought the total paid out in 1868 to $12.8 million in cash, plus over $4 million in UP stock (at par value of $100 per share), bringing the total of stock distributed since 1867 to $28.8 million.1

To Brigham Young, this was outrageous. Beginning in January and continuing through the year, he would dun Doc to pay up. “I have expended all my available funds in forwarding the work,” he wrote on January 16. If he could he would continue to do so, but he was out of funds. “These explanations must be my apology for troubling you in the matter.”2 More followed, with supporting details. “The men are very clamorous for their pay,” Young informed Durant. There was some three-quarters of a million dollars yet due them. They had done and were doing the work and “have now waited from half to three quarters of a year for their pay.” Six months later, Young was still trying. “To say the least,” he declared in one letter, “it is strange treatment of my account after the exertions made to put the grading through for the Company, It is not for myself that I urge, but for the thousands that have done the work,” One UP official told Young, “It is a good thing for us that your people did the work, for no others would have waited so long without disturbance.” Young quoted this back to the UP, but still—this was in November 1869!—couldn’t get paid.3

A corporation that pays nearly 300 percent cash in dividends on invested capital in just one year but cannot pay what is owed to its workers is in big trouble. For the UP and its construction company, the Crédit Mobilier, the trouble was bigger than big. In January 1869, the respected North American Review printed an article by Charles Francis Adams, Jr. Adams was a member of the Massachusetts Board of Railroad Commissioners and a grandson and great-grandson of U.S. presidents. The article was entitled “The Pacific Railroad Ring.”

Adams’s target was the Crédit Mobilier. He called it “but another name for the Pacific Railroad ring.” He charged that “the members of it are in Congress; they are trustees for the bondholders; they are directors; they are stockholders; they are contractors; in Washington they vote the subsidies, in New York they receive them, upon the plains they expend them, and in the ‘Crédit Mobilier’ they divide them.”

Adams described them as “ever-shifting characters” and charged “they are ever ubiquitous; they receive money into one hand as a corporation and pay it into the other as a contractor…. Under one name or another, a ring of a few persons is struck at whatever point the Union Pacific is approached.”4

At that time, Adams’s “ring” was bigger than his phrase “a few persons” implied. The stockholders consisted of ninety-one individuals, only seven of whom were in Congress (including Grenville Dodge and Oakes Ames).5 But that didn’t matter. What did matter was that the money that flowed from the Union Pacific into the Crédit Mobilier and what was done with it—which wasn’t to pay the contractors, the subcontractors, or the laborers who had gotten the railroad from Omaha to the Utah border—was further enriching a relatively few already wealthy men who milked the corporation, the government, and ultimately the people for their fat and ill-gotten profits. “Greedy interests are stimulated into existence,” according to Adams, and they “intrigue and combine and coalesce, until a system of political ‘rings,’ legislative ‘log-rolling,’ and organized ‘lobbies’ results; and then, at last, the evil becoming intolerable, the community sluggishly grapples with it in a struggle for self-preservation.”6

Or so at least Adams wrote. In the process he was preparing the ground for the planting of a seed that might someday sprout and could then grow into the largest scandal in nineteenth-century American history. He was pointing the way and providing the means for politicians, some of them venal, others upright and genuinely and rightly concerned, to go after the Crédit Mobilier, potentially to ruin the shareholders and perhaps the UP itself.

Which was only fair. It was democracy that had made the UP possible. If the company was to be attacked without mercy, even after it built more than half of the road that everyone wanted, it was fitting that the representatives elected in the democratic system do it.

By no means was it just Adams who went after the UP. As its moment of triumph approached, there were many others ready to launch an assault.

THE CP had its own severe problems. Money, of course. Huntington could never sell enough of the company’s own stocks and bonds, or gather in enough of the government bonds for grading and tracking, to pay the bills. Questions abounded. Would the company’s rails get to Ogden before the UP? Could they go east from Ogden up the Weber River Canyon? Up Echo Canyon? More realistically, could the CP rails reach Promontory before the UP? How much of the grade the company had built and was building in Utah would it be able to use?

The corporation was also vulnerable to the kind of charges Adams had brought against the UP. Charlie Crocker’s Contract and Finance Company was like the Crédit Mobilier in so many way that the firms were like two peas in a pod, except that the Big Four plus E. B. Crocker held all the stock of the Contract and Finance Company secretly. As to Adams’s implication that the UP had been involved in bribery (how else to explain why so many congressmen held Crédit Mobilier stock?), the CP could hardly stand a close examination of Huntington’s accounts.

Huntington had been in Washington with large sums of money at his disposal whenever Congress took up a question in which his railroad had a consuming interest. He had left Washington considerably lighter in his pocket, but with a favorable vote. An investigation of the UP’s finances would only help the CP. But what if the politicians, having gotten into the matter, decided to broaden the inquiry to include the CP?

THE two corporations shared other problems. One was material. On January 1, 1869, the CP had thirty-five ships bound for San Francisco. They were bringing essential construction materials, including eighteen locomotives. As the Salt Lake Daily Reporter noted, “There is not a rail on the CP line of the road that has not been brought a distance of six thousand miles.”7 In Truckee, the sawmills worked around the clock to meet the CP’s orders for a million ties. In Omaha, UP ties were piled up in the yards, awaiting shipment. One of Casement’s orders for ties alone required hauling six hundred flatcars a distance of four hundred miles. Even after the ties were delivered along the grade, it took six or more carloads to supply enough material to lay one mile of track.

There were always shortages on both sides. Some were caused by the vagaries of ocean travel. “We have in Cal. 183 miles iron and only 89 miles spikes,” Crocker telegraphed Huntington on January 20, “and 81 miles iron and 75 miles spikes to arrive in sixty days. It is very unsafe to half-spike the track at this season of the year.” That same day, Hopkins asked Huntington by telegraph, “Will you send spikes by steamer to make up deficiency?”8 That would cost more, but then, Huntington often said he never did anything until he had Mark Hopkins’s approval.

STROBRIDGE had a talk with Charlie Crocker. “I don’t like to have those Union Pacific people beat us in this way,” Strobridge declared. “I believe they will beat us nearly to the State Line”—that is, between Nevada and Utah.

“We have got to beat them,” Crocker replied. He thought it could be done.

“How?” Strobridge asked. “We have only got ten miles of iron available.” But Crocker would not give up his hopes. When Jack Casement’s men of the UP laid four and a half miles of track in a single day, Crocker said that “they bragged of it and it was heralded all over the country as being the biggest day’s track laying that ever was known.” He told Strobridge that the CP must beat it, and Stro got the materials together and laid six miles and a few feet. So Casement got his UP men up at 3 A.M. and put them to work by lantern light until dawn and kept them at it until almost midnight, and laid eight miles. Crocker swore he would beat that.9

WEATHER was against both companies, although this was mainly their own fault, because they insisted on building through the winter. The CP’s grading and track laying were at altitudes of up to five thousand feet and sometimes higher. At Humboldt Wells, Nevada, and to the east into Utah, where Strobridge’s graders were at work, temperatures went to eighteen degrees below zero in mid-January and stayed that low for a week. By the end of the cold spell, the soil was frozen solid to a depth of nearly two feet. The graders could not use their picks or shovels. Instead, they blew up the frozen ground with black powder.* The explosion split the earth into big pieces. Crocker called it building grade with “chunks of ice.” When warm weather came in the spring, he recalled, “this all melted and down went the track. It was almost impossible to get a train over it without getting off the track.”10

Thirty-year-old Henry George, the future economist, at that time a reporter for the Sacramento Union, rode over the track in April and wrote that it had been “thrown together in the biggest kind of a hurry.” His train, he said, often could move no faster than an ox team.11

Sometimes the trains did not move even that fast. In mid-February, a week-long storm came over the Sierra Nevada. The Reno Crescent said that up in the mountains the storm was “described as something awful.” Two CP locomotives made it across on the front edge of the storm, with enough iron to lay two miles of track, plus “sixteen cars loaded with ties, four cars loaded with bridge timber, a caboose and passenger cars.”12 After the trains arrived, the storm hit, hard—it was the worst of the winter. Back near Cisco, a snowslide knocked out a trestle bridge and caused a blockade. Several passenger trains were snowbound, and not even nine locomotives pushing one of the largest of the CP’s plows could get through the drifts.

The slides came in those fourteen miles the CP had not yet covered with their sheds. The good news from the storm was that the snowsheds already built had held up throughout the onslaught. More good news: within a week, the snow had melted and the trains were running again.13

For the UP, the weather was equally awful and lasted longer. On January 10, a snowstorm hit Wyoming. The wind was up—indeed, so fierce that snowdrifts covered much of the line. It took a freight train bound for Echo with construction supplies fourteen hours to make the last forty miles. Following the storm came a savage cold wave. For a week the temperature never climbed above zero, and on January 17 it sank to twenty degrees below zero. At Wasatch, a town laid out by Webster Snyder, the UP’s general superintendent for operations, which was the winter headquarters for the Casement forces, desperate work was going on to board up the rough-hewn buildings. “The sound of hammer and saw was heard day and night,” wrote J. H. Beadle as he tried to drink his coffee in a cafe whose weatherboarding was being applied as he had his breakfast. But gravy and butter froze on his plate. Some spilled coffee congealed on the table.

Graders worked in overcoats, which slowed them down considerably. They blasted the frozen ground with black powder, just as the CP’s graders had done. The results were equally disconcerting. When the thaw came, an entire train and the track beneath it slid off the grade made with “chunks of ice” into a gully.14 Superintendent Reed wrote his wife how much he was looking forward to completing the job. When that happened, “I shall want to leave the day after for home, and hope to have one year’s rest at least.”15

In February, the storm that had stopped nine CP locomotives in the Sierra came to Utah. “The most terrific storm for years,” according to one Salt Lake City newspaper. When it hit Wyoming, the storm shut down ninety miles of the UP line, between Rawlins and Laramie, for three weeks. Two hundred eastbound passengers were stuck in Rawlins, six hundred westbound marooned at Laramie. The eastbound passengers were headed for Washington, D.C., to be there for the inaugural of President Ulysses S. Grant, elected overwhelmingly in November.

On February 15, Dan Casement set out from Echo to rescue them, with a road-clearing crew and a big plow. But he found the cuts filled with twenty-five feet of snow and could move forward only five miles per day at best. Then he and some others decided they would have to walk the rest of the way to Laramie, some seventy-five miles. He almost died—or, as his brother Jack put it, “came near going up”—before he finally made it. He reported to Jack, “Have seen a cut fill up in two hours that took one hundred men ten hours to shovel out.” His men, he said, “are all worked out and frozen.” It was “impossible to get through.” As for the trains, they “can’t more than keep engines alive when it blows.”16

No one east of the Missouri could imagine what it was like. Webster Snyder said, “New York can’t appreciate the situation or the severity of a mountain snow storm.” Durant’s answer was to wire Snyder to send eight hundred flatcars to Chicago. “If you can’t send the cars,” he warned, with his usual gracelessness, “send your resignation and let some one operate the road who can.”17

On March 4, Grant became president even before the would-be celebrants stuck in Rawlins got as far as St. Louis. When they arrived, one of them said, “Most of us are much the worse for wear, and we think it will be a long time before we take another ride over the mountains on the Union Pacific Railroad.”18

“Have We a Pacific Railroad?” asked the New York Tribune of March 6, 1869. Not if passengers were stranded in the Wyoming desert and mails detained for three weeks by a mere snowstorm.19 Passengers stranded on the line wrote extremely angry letters to the newspapers. Fifty of them signed a letter to the Chicago Tribune which said that the workmen had refused to help them in any way because “for near three months they had not been paid.” Further, as far as they were concerned, the UP was “simply an elongated human slaughter house.”20

Webster Snyder noticed that some of the letters came from employees of the Central Pacific and wrote his own to friendly newspapers, only to discover that in New York the dailies refused to print letters favorable to his company. No wonder, since their journalists criticized the UP without any attempt at balance (it was, after all, the worst storm in memory).

ACCIDENTS on the lines were frequent. On January 18, a new CP locomotive, named Blue Jay, chugged into Reno looking “prettier than a spotted mule, or a New York school ma’am,” according to the Crescent. Three days later, it chugged back up the Sierra, headed west with a few carloads of passengers, only to run into a stalled lumber train. The Crescent reported that, “bruised, broken, and crippled, it was then taken limping to Sacramento for repairs.” Several cars were smashed, “but fortunately nobody was killed.” One construction train uncoupled in the middle as it was coming down the long grade into Reno. The front half of the train got well ahead, but then the aft cars gained momentum and hit the last car of the front half. The collision splintered eleven cars and crushed two brakemen.21

On the western slope, two Chinamen cutting ties felled a tree across the track. They were engaged in cutting it into lengths for ties and were so intent on the work that they failed to notice the approach of the locomotive. The engineer, coming around a curve, failed to notice the Chinese. Both were run over.22

For the UP, during the great February storm, Engine 112 was overwhelmed by its attempt to plow through the snow. The boiler strained until it could do no more and exploded from the effort. The engineer, fireman, and conductor were all killed, as was a brakeman who was crushed by an overturning car.

As 1868 drew to a close, for one unit of the great UP and CP armies the war had ended. The survey engineers had completed their task—for the UP all the way to Humboldt Wells, for the CP to the head of Echo Canyon. The survey parties were disbanded to cut down expenses.

Some surveyors stayed on to work with the construction contractors, and others went off to lay out lines for new roads. In Maury Klein’s words, “They could take pride in a job well done.” Nothing accomplished by either company “was more impressive or enduring than the final line located through a forbidding, unmapped wilderness bristling with natural obstacles.” Anyone can see for himself in the twenty-first century by driving Interstate 80 from Omaha to Sacramento. Nearly all the way, the automobiles will be paralleling or very near the original grade as the surveyors laid it out. “In later years,” Klein wrote, most of the surveyors would look back on their time laying out the line of the first transcontinental railroad “as the most exciting chapter of their careers.”23 It was also the best work they ever did. Every citizen of the United States from that time to the present owes the surveyors a debt of gratitude that can never be repaid.

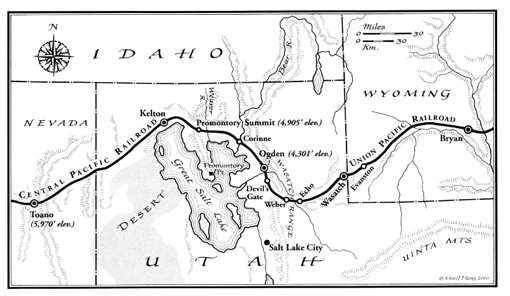

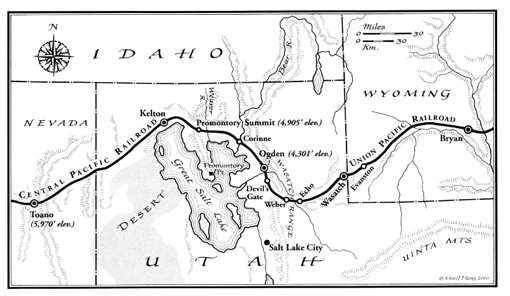

It was almost as exciting for many of the graders and their foremen. And for them, the first month or two of 1869 were the most memorable. Much of that time, the two companies worked within sight of each other, often within a stone’s throw. On January 15, Stanford wrote to Hopkins to say he thought the CP should get as far as Ogden. To claim more, as Huntington was doing, Stanford thought was “to weaken our case.” Going west from Ogden to Bear River, the grading lines of the two companies “are generally from 500 feet to a quarter of a mile apart, but at one point they are probably within two hundred feet.” Between Bear River and Promontory, the UP was close to the CP “and crosses us twice,” with other grades running “within a few feet of us.”24

On the rocky eastern slope of the Promontory Mountains, a large gang of Strobridge’s Chinese were grading to the east, while Casement’s graders were building to the west. They were frequently within a few feet of each other. They worked fast, hard, all day long, even though it was obvious to them that one side or the other was wasting time, labor, and supplies. The two grades paralleling each other can still be seen, often nearly touching, occasionally crossing.

The UP’s crews were mainly Irish. They tried to shake the persistence of the Chinese by jeering and by tossing frozen clods at them. The tactics had no visible effect, so they attacked with pick handles. The Chinese fought back, to the Irishmen’s surprise. So the Irish tried setting off heavy powder charges without warning the Chinese, timing them to explode when the CP grade was closest. Several Chinese were badly hurt. The CP made some official protests. Dodge gave an order to cut it out. He was ignored.

A day or two later, when the grades were only a few yards apart, the Chinese set off an unannounced explosion. It deposited a cascade of dirt and rocks on the UP’s Irishmen, several of whom were buried alive. That ended the war.25 The grading crews, however, went on scraping furiously in parallel lines beside each other but in opposite directions.*

The track layers were not in sight of each other, but they were aware of how well the rival line was doing, and they put their entire effort into the job. Never before, or since, has railroad track been laid so fast. By January, the UP’s track was in Echo City, only eight miles from the mouth of Echo Canyon. The first locomotive got there at 11 A.M. “And Echo City held high carnival and general jubilee on the occasion.”26

There was trouble, however. The tunnel just beyond Echo went slowly. It was the longest of the three tunnels the UP had to drill and dig in the Wasatch Range, 772 feet long with deep approach cuts. Though work had started in the summer of 1868, it was far from completed. No nitroglycerin was used, but excavating the tunnel consumed 1,064 kegs of black powder. Meanwhile, the UP workers bypassed the tunnel with a flimsy eight-mile temporary track over a ridge.

The two tunnels to the west were less than a mile apart in the canyon, perched on narrow, curving ledges above steep, rocky gorges. On these tunnels, nitroglycerin was used to speed up the work. A fifth of the tunnel men protested vainly and walked off the job. The remainder used the nitro to make the work go faster. Nitro then ripped out the tunnels at a record pace of eight feet a day.

On January 9, the track reached a tall, ancient pine that stood next to the grading in Weber Canyon. That pine marked precisely the point where the tracks were a thousand miles from Omaha. It surely deserved to be memorialized, so a sign reading “1000 Mile Tree” was hung from its lowest limb. Andrew Russell took a picture, often reproduced, and the base of the tree became a picnic spot for tourists.

By the end of January, light shone through the largest tunnel, the one closest to Echo. The headings had met. The bottoms remained to be blasted out, a job not completed until April, and not until the middle of May was track laid through it.

THE CP spent January laying track from Elko toward Humboldt Wells. On the 28th of that month, the tracks were 150 miles west of Elko. After getting to the Wells, the track would run northeastward to the state line, then on toward Promontory. But Humboldt Wells was still 224 miles from Ogden, and the CP had not yet reached it.

Charlie Crocker came, saw, and threatened the Chinese crews. According to one foreman who was there, “He stirred up the track layers with a stick; told them they must do better or leave the road.”27 That got them to working even faster.

One day, at the end of track, a supply train came up. It carried no rails, only ties. Crocker went back to the forwarding station to confront the man responsible, a man named McWade. As soon as he saw Crocker, McWade called out, “Mr. Crocker, I know about it. Mr. Strobridge has telegraphed me, and I know it was all wrong and I am sorry.”

Grim-faced, Crocker replied, “Mac a mistake is a crime now. You know what we have been trying to do. You know how I have been going up and down this road trying to get the material to you. And here it is—and you have made a mistake and thrown us out of two miles of track today. Now take your bundle and go. I cannot overlook it.”

McWade burst out crying. Finally, he managed to say, “Well it is pretty hard on me. I have been a good, faithful man.”

“I know you have,” Crocker replied, “but there has got to be discipline on this road, and I cannot overlook anything of this kind. You must go. Send your assistant to me.”

Crocker put the assistant in charge. But, having made his point, he relented. “I let him lay off a month,” he said of McWade, “and put him back again. But it put everybody on the alert, and kept them right up to their work. And it did good, because everybody was afraid, and when I came along they were all hard at work, I can tell you.”

Discussing the incident years later, Crocker added, “It got so that I was really ashamed of myself.”28

AS always, finance was a special problem for the UP. The track layers struck, for $3.50 per day. The UP had no choice with regard to these skilled workers and paid what was demanded. They, and all other workers, also got double pay on Sundays. The Mormon workers demanded $5 a day for a man and team, $10 on Sunday, and at least on paper got it, though they were not paid. When Mormon subcontractors refused work in spring sinks or heavy cuts, Casement flung his tireless Irish into the breach.29

On January 4, Snyder had reported to Dodge, “In construction the waste of money is awful…. We are ditching trains daily. Grading is done at enormous expense. The ties cost $4.50 each on the ground…. The company can’t stand such drafts as I know the Construction Department must be making…. Would like to know what I am to be paid.” Twelve days later, Oliver Ames wrote Durant: “Everything depends on the economy and vigor with which you press the work. We hear here awful stories of the cost of the work…. The contract price for ties is but one dollar.”

The bosses had turned on each other. On February 3, Durant had telegraphed Dodge to inform him before issuing orders, as always. “If you cannot find time to report here I shall of necessity be obliged to supersede you.”30 A strange threat to be given to a man who had the President-elect’s full confidence, and of whom Oakes Ames had declared, “Dodge is a perfect steam engine for Energy. He is at work night and day.” And for Durant, Oakes had his own threat. “We must remove him from the management,” he declared, “or there is no value to our property.”31

Such was the word from company headquarters in New York. In Omaha, the bankers were demanding their money, $200,000 in over-drafts from the Omaha National alone. Herbert Hoxie told Dodge, “We must have $750,000 and it ought to be twice that.” Oliver Ames had calls for $2 million with neither cash to give nor collateral to get it. Out on the line, where the work was being done, everyone who counted was upset. “I am afraid the Union Pacific is in a bad way,” Jack Casement wrote his wife. Sam Reed, covering forty to sixty miles a day on horseback to oversee the crews, told his wife, “Too much business is unfitting me for future usefulness. I know it is wearing me out.” But it wasn’t so much the work as the financial strain. Reed added, “The Doctor himself, I think, is getting frightened at the bills.”32

IN Washington, the UP had but to wait before it got ahead of the CP. The Andrew Johnson administration would give way on March 4, 1869, to the Ulysses Grant administration. The President-elect and the high command in the army were as close as could be with Grenville Dodge, and friends with the Casements along with other UP officials. Whereas Johnson’s Cabinet had favored the CP whenever possible, Grant’s could be expected to lean toward the UP.

It all came down to the government loan of bonds to the railroads for miles graded and track laid, and specifically down to which road would get them for the line between the north end of the Great Salt Lake and Echo Summit. Huntington had filed with the Department of the Interior his guesswork map covering the distance, and Secretary Browning had accepted it. Stanford then proceeded on the assumption that the CP’s line on a map, even if little work had been done on it east of Ogden, was the true line of the Pacific railroad, and the only one on which subsidy bonds could be issued. Huntington intended to snatch them. He had filed in Washington for $2.4 million in subsidy bonds, two-thirds of the amount due for that portion of the line.

Dodge and the Ames brothers had hurried to Washington to block Huntington. They were successful, at least to the degree of persuading Browning to hold up issuing the bonds until a special commission had reported to him on the best route through the disputed territory. Huntington responded to Browning’s holdup with a curse and a comment, “The Union Pacific has outbid me.”33

On January 14, 1869, Browning had given the commission his instructions. He ordered the commissioners to “make a thorough and careful ex-amination” of the ground between the two ends of track. If either of the lines was “in all respects unobjectionable,” they were authorized to adopt it. If not, they should make a new location. “You will also designate a point at which the two roads will probably meet.”34

Browning’s actions caused delay, which he must have intended and which was probably the best he could do as a lame duck. Oakes Ames came to Huntington’s hotel room to see if the two roads could make their own settlement. Why not simply split the remaining distance between the two railheads, Ames suggested. That would suit the UP, since it would put the meeting point west of Promontory.

“I’ll see you damned first,” Huntington snarled. How about the mouth of Weber Canyon? he countered. That would greatly benefit the CP.

Ames replied with his own curse. The two men broke off, met again, snarled once more, broke off, met again, until Huntington finally agreed to a joining at Ogden. Beyond that point, he swore, he would not budge.

On January 29, Stanford discussed the matter in a letter to Hopkins. The commissioners would begin their examination on February 1, he said, “and from the instructions and straws in the wind I fear this thing is set up against us. The far off distance of our track and slow progress works against us with great force. It is trying to ones nerves to think of it.”

Stanford blamed not Ames or anyone else with the UP, or Browning, but Huntington. In Stanford’s view, Huntington was “trying to save what a want of foresight has jeopardized if not lost. I tell you the thought makes me feel like a dog; I have no pleasure in the thought of Railroad. It is mortification.”35

ON February 16, the CP was twenty miles east of the Wells, this at a time when the UP was twenty miles east of Ogden with its track. The CP’s biggest problem was not laxness on the Chinese crews’ part, but get-ting supplies up to the end of track, brought on not by McWade’s mistakes but by haphazard ship arrival in San Francisco and by the blockage caused by the great storm in the Sierra.36

A lack of locomotives was not the cause. Huntington had shipped them to California almost faster than Crocker could use them. The Reno Crescent’s editor called the roll of the new ones to make their way through his town: Fire Fly, Grey Eagle, Verdi, Roller, White Eagle, Tiger, Hurricane, Jupiter, Mercury, Herald, Heron. There was no apparent limit.37

By February 29, the CP had made another twenty miles in thirteen days, which for all previous track-laying crews would have been spectacular progress but for the CP was disappointing. The line was forty miles east of Humboldt Wells, almost into Utah, but it was still 144 miles from Promontory. The UP on that date had track up to Devil’s Gate Bridge on the Weber River and was thus but six miles from the mouth of Weber Canyon and sixty-six miles from Promontory. But the CP was closing the gap.

PROMONTORY Summit was a flat, almost level circular basin more than a mile in width. It stood a little more than five thousand feet in elevation, some seven hundred feet above the level of the lake. It separated the Promontory Mountains to the south from the North Promontory Mountains and stood at the northern end of the Great Salt Lake, or the beginning of the thirty-five-mile-long rugged peninsula that thrust itself into the lake.

There was no terrain problem in grading and laying track across the summit basin, but getting up to it on either side was difficult. On the west side the approach was over sixteen relatively easy miles, but on the eastern slope the ascent required ten tortuous miles of climbing at eighty feet to a mile, including switchbacks. For the UP this was the last stretch of difficult country. There were projecting abutments of limestone to cut through, and ravines requiring fills or bridges. The most formidable of the ravines was about halfway up the eastern slope.

The CP had got there first. It was a gorge of about 170 feet in depth and five hundred feet long. On either side there was black lime-rock that had to be cut through, sometimes at heights of thirty feet and always as much as twenty feet. In November 1868, Stanford, accompanied by two of his engineers, arrived to see it. He took one look at the projected line and ordered Clement to lay out a new one to avoid an eight-hundred-foot tunnel through solid limestone. Clement said that was going to be an awfully big fill. Stanford agreed, predicting that it would require ten thousand yards of earth.

In early February, the CP put five hundred men, Mormons and Chinese, to work. They were supplemented by 250 teams of horses, to pull the carts that carried the earth to the fill sites. One by one they came forward, tipped the cart, and returned for the next load. One hundred fifty feet above, on each end at the top of the gorge, blasting crews were at work. They used nitroglycerin and black powder to make the cut. They made the holes for the explosive with drills, just as had been done at the tunnel facings, or, if one was available, they used crevices in the stone. After pouring in the powder, they worked it down with iron bars.

Sometimes the bars striking the rocks sent off sparks that set off the nitro or the powder. Huge rocks were sent tumbling down the mountainside. Once a man was blown two or three hundred feet in the air. When he came down he had broken nearly every bone in his body. The same blast burned a few others, and three were wounded by flying stones. On another occasion three mules were killed by an unexpected blast.38

It took almost three months to make the fill. It is still there today, still causing viewers to gasp and to shake their heads in disbelief, especially if they are carrying a photograph showing how the UP overcame the gorge.

Had either railroad built a causeway or bridge across the Great Salt Lake, most of the difficult work could have been avoided and many miles saved. Dodge thought about it, put enough energy into it to have the lake sounded, and decided it couldn’t be done. In 1868, the lake was fourteen feet higher than it had been in 1849, when first sounded. It was not feasible to build, Dodge decided, because “the depth of the lake, the weight of the water, and the cost of building was beyond us, and we were forced north of the lake and had to put in the high grades crossing Promontory Ridge.” By the time the Union Pacific put in the causeway at the beginning of the twentieth century, the lake was eleven feet lower than when the original survey was made.39

HUNTINGTON labored in Washington. He had called at the office of Secretary of the Treasury Hugh McCulloch almost every day in January, to demand the CP’s bonds for advance construction work as far as six miles east of Ogden, but Secretary McCulloch was always too busy to see him. Huntington was sure the CP was entitled, because Secretary Browning had approved his map. And if the CP got the government bonds for the route from Promontory to east of Ogden, obviously the UP could not be entitled, because the government was not going to give away two sets of bonds for a line through the same territory.

Huntington began to “bring different influences to bear on the Secretary.” He got a report from Browning’s office stating that the CP was entitled to the bonds. He also got the solicitor of the Treasury to sign a similar report.40 Still no action.

Thanks in part at least to Huntington’s lobbying, his request for subsidy bonds was brought up for discussion in a Cabinet meeting on February 26—that is, at a time when the Johnson administration had less than a week to go. Browning appeared before the Cabinet and got McCulloch to agree with him, but the Cabinet put off any decision until Monday, March 1. At that meeting, with Grant to be inaugurated on March 4, the Cabinet voted unanimously to approve the CP’s request for bonds and formally directed Secretary McCulloch to release them.

“But McCulloch still refused to let me have them,” Huntington later recalled. In his opinion this was due to McCulloch’s having had a talk with Oliver Ames, which may have been true: Ames must have felt that once Grant was in office McCulloch would be gone and the vote of the Johnson Cabinet would amount to nothing. Whatever the explanation, Huntington was taking no chances. He went to the secretary of the Treasury’s office, demanded to see him, then announced that he would sit in McCulloch’s anteroom for two weeks if he had to but he was not going to leave without the bonds. McCulloch consulted with his assistants, then declared, with a sigh, “He shall have them.” Huntington went back to his hotel room, and by 8 P.M., “I had the bonds. They amounted to over $2,400,000.”

The money covered the line in advance of the completed track from Promontory to six miles east of Ogden. Oakes Ames had just talked to McCulloch, who had assured him that no bonds would be issued in advance of completed track, and President Johnson had told both Ames and Dodge “that no such bonds should be issued.” The UP had just lost $32,000 per mile in bonds (a total of $2.5 million), plus the right to issue the same amount of their own first mortgage bonds, plus the grants of land. But the directors didn’t yet know that they had lost.

Huntington stuffed the bonds into his satchel and got on the train to New York. “This was the biggest fight I ever had in Washington,” he wrote Hopkins, “and it cost me a considerable sum.” Three days later, Grant was inaugurated. His first order, released on the evening of his inaugural, was directed to two members of his Cabinet. One was the new secretary of the interior, Jacob Dolson Cox, formerly a division commander under Sherman during the war and the governor of Ohio. The other was the new secretary of the Treasury, George Sewall Boutwell, a former congressman from Massachusetts and a friend as well as colleague of Oakes Ames. The order was to suspend action on the issue of further subsidy bonds to the CP and the UP.41

Stanford, Huntington, and the other two members of the Big Four had hoped for more. The $2.4 million was the subsidy from Promontory to Ogden, but the CP had hoped to go at least as far as Echo Summit. On March 7, 1869, however, less than a week after Huntington got the bonds, the UP laid tracks into Ogden, 1,028 miles from Omaha. This ended the dispute as to which line had the right-of-way east of the town. (At the time, Crocker’s rails were 184 miles away from Ogden.)

On March 14, Stanford in Salt Lake City wrote Hopkins to inform him, “They [the UP] have laid track about three miles west of Ogden.” He did not have to add what Hopkins already knew, that the delivery of bonds to Huntington for the grading from Promontory down past Ogden by the CP had already happened. Stanford did tell Hopkins that if the UP were aware of what the government had done “they would call off their graders.” But in their ignorance, the UP was going all out on the heavy work at Promontory. Let them, was Stanford’s attitude. “We shall serve notices for them not to interfere with our line and rest there for the present.”42

GRANT’S order to stop any handing out of subsidies may have helped the UP, at least for a time, but it was not enough. The company owed the banks $5.2 million in loans, owed its contractors and subcontractors, superintendents, engineers, foremen, and workers $4.5 million, owed others who knew how much. It had not a cent available to pay. Brigham Young wrote Durant at this time that the Mormons had completed the fill near the head of Echo Canyon. He recounted that the Doctor and two of his, Young’s, sons had stood at the spot a couple of months ago to make a contract for the work. As Young quoted him, Durant had said, “If we would keep on a large force, and rush the work, I’ll pay you what it is worth.” On that basis the job was done. All Young was asking was for his people to be paid, and that at a rate 40 percent below what the CP was paying for similar tasks.43

Good luck to Young on collecting. Durant not only ignored him, but at the same time sent a wire to Dodge that was notable, even for Doc, in its brazenness. “You have so largely over estimated the amounts due Contractors,” he said, “that it becomes my duty to suspend your acting as Chief Engineer.”44

Dodge had meanwhile met with Grant three days before the inaugural. Grant had told him that there was evidence of a “great swindle” in the estimates for UP work done in Weber Canyon. As soon as he became president, Grant warned, he was prepared to force a complete reorganization of the road. Dodge then gave orders that at the next meeting of the board, scheduled for March 10, Durant must be voted out.45

Good luck on holding that meeting. James Fisk, known as the “Barnum of Wall Street,” had just bought six shares of UP stock at $40 each, a total of $240. He was working with Durant, as he had previously worked with financier Jay Gould. With the assistance of the mayor of New York, Boss William M. Tweed, and Judge George Barnard of the New York State Supreme Court in Manhattan, Fisk and Gould had taken control of the Erie Railroad away from financiers no less renowned than Cornelius Vanderbilt and financier Daniel Drew. Now he was after the UP.

No dividend had been paid on his six shares of the UP. Fisk claimed that he had been deprived of his rights because the Crédit Mobilier was absorbing all the profits of the UP. He got Judge Barnard to declare the UP bankrupt and had the judge appoint a receiver, who was, not surprisingly, William M. Tweed, Jr., son of the “Boss.” On March 10, Fisk got an order that let him send in the sheriffs to break up the UP’s stockholders’ meeting. The officers of the law arrived at the Fifth Avenue Hotel in New York City with warrants to arrest the directors. Oakes Ames claimed congressional immunity and sneaked away successfully, but his brother Oliver was arrested and held until he could produce a $20,000 bail in the morning. This was the meeting at which the officers had planned to vote Durant out of office. So much for that.46

The New York newspapers had a grand time with the whole thing. “Prince Erie’s War Dance,” blasted one headline. But the editors could not keep themselves from supporting Fisk, because of what one called the “peculiar relations” between the UP and the Crédit Mobilier that Fisk was attacking. The theme became the Rogue as Reformer, which seemed to fit the engaging chap named Fisk. All the directors of the UP, meanwhile, believed that Durant was behind the whole thing.

The UP appealed to Congress. It took nearly a month for that body to take up the matter.

• • •

OUT in Utah, both lines were laying track as fast as could be done. Hopkins sent a telegram to Huntington, “Roving Delia Fish Dance,” which meant when decoded, “Laying track at the rate of 4 miles a day.”47 The UP had laid out the new town of Corinne, five miles west of Brigham City, on the east side of the Bear River. It was a Hell on Wheels built of canvas and board shanties. On March 23, the Salt Lake Deseret News wrote, “The place is fast becoming civilized, several men having been killed there already, the last one was found in the river with four bullet holes through him and his head badly mangled.”

Photographer Russell took a photograph of Corinne. He must have taken it at first light, for there is but one horse and no people to be seen. The shacks and tents are laid out haphazardly. Not all of them were taverns. Three of the nearest buildings are eating houses: “Germania House, Meals 50 cents,” “Montana House, Meals 50 cents,” and “Montaine House, City Bakery.” Off at the far left is an apparently improbable place of business, the “Corinne Book Store.”

Jack Casement, driving the work forward by night as well as by day, had just about had enough. “I am perfectly homesick,” he wrote his wife. When the job was over, “I think I would like to work in the garden or build a house.”48 But his spirit revived, because the weather was beautiful, the mud drying fast. Rafts were coming down the Bear River carrying pilings and telegraph poles. The UP had five pile drivers at work preparing for building a bridge over the river, while the CP had one at work. Both lines were being vigorously prosecuted. The Deseret News wrote, “From Corinne west thirty miles, the grading camps present the appearance of a mighty army. As far as the eye can reach are to be seen almost a continuous line of tents, wagons and men.”

What a scene it was. Even for men who had been in the war, which included most of the UP crews, foremen, and superintendents, and many of the non-Chinese in the CP’s camp, it was a striking, never-to-be-forgotten image. Russell and Hart, who had seen and photographed great numbers of men in battle and in camp, were inspired to do some of their best work here. They were up before dawn, setting their cameras, getting their plates ready, taking pictures through the day, and keeping at it until the light faded. Everyone who was there knew that, except for the war, there had never before been in North America, and never would be again, a sight like this one. They all soaked it up.

The area twenty-one miles west of Corinne, where the ascent of the Promontory Mountains began, was “nearly surrounded by grading camps.” The blasting crews were “jarring the earth every few minutes with their glycerine and powder, lifting whole ledges of limestone rock from their long resting places, hurling them hundreds of feet in the air and scattering them around for a half mile in every direction. One boulder of three or four hundred pounds weight was thrown over a half mile and completely buried itself in the ground.”

The lines were running so near each other that, according to the reporter, “in one place the UP are taking a four feet cut out of the CP fill to finish their grade, leaving the CP to fill the cut thus made.” Who was ahead, the reporter (whose pen name was “Saxey”) didn’t know, or at least didn’t want to say. But for sure they were going to meet somewhere.

Meanwhile, between Promontory and Brigham City, “I will venture the assertion that there is not less than three hundred whisky shops, all developing the resources of the Territory and showing the Mormons what is necessary to build up a country.”49 Dodge had put engineer Thomas B. Morris in charge of the Utah Division. In his diary Morris recorded, “Rode to Brigham City—found camp there. G.L. drunk—had him arrested—hunted up bed in storehouse. Discharged L. Pratt & Van Wagner—drunk—saw G.L. & left him locked up.” A couple of weeks later, “Settled up with George & Walter—the latter I discharged for impudence.” Four days later, “Stayed all night at Fields—good supper & bed behind the bar.”50

THE UP got its bridge built first, and on April 7 its first locomotive steamed over the Bear River to enter Corinne. The CP was still almost fifteen miles west of Monument Point. But the CP had its “Big Fill” completed, whereas the UP had just gotten started (March 28) on its attempt to cross the gorge. Strobridge had decided he could save time by building a trestle bridge, to be called the Big Trestle, about 150 yards east of and parallel to the Big Fill. The UP’s line could be made a fill later.

The Big Trestle took more than a month to build and was not completed until May 5. It was four hundred feet long and eighty-five feet high. One reporter said that nothing he could write “would convey an idea of the flimsy character of that structure. The cross pieces are jointed in the most clumsy manner.” In the reporter’s judgment, “The Central Pacific have a fine, solid embankment alongside it [meaning the Big Fill], which ought to be used as the track.” Another correspondent predicted that riding on a passenger car over the Big Trestle “will shake the nerves of the stoutest hearts of railroad travelers when they see that a few feet of round timbers and seven-inch spikes are expected to uphold a train in motion.”51

THE race,” Dodge had declared on March 23, “is getting exciting & interesting.”52 This was so in New York as well as in Utah. On the East Coast, Fisk got an order from Judge Barnard giving the receiver, young Tweed, the power to break open the safe at the UP’s headquarters, 20 Nassau Street. On April 2, he came in with eight deputies armed with sledgehammers and chisels. Tweed announced that they were going to break open the company’s safe. It took hours. When the safe finally yielded, it was discovered that most of the UP’s records and documents had disappeared.

A different sort of fight was taking place in Washington. Congress debated the railroads. Senator William M. Stewart from Nevada, a staunch friend of the CP, described with gusto and in detail the sins of the UP. He was supported by Senator James Nye, also of Nevada. Picking up on Charles Francis Adams’s article on the Crédit Mobilier, Stewart declared, “Leading members of Congress, members of the committee on the Pacific Railroad in the House, were not only in the Union Pacific but in this identical Crédit Mobilier, and were the recipients of enormous dividends.” That was surely ominous for the congressmen who held Crédit Mobilier stock, but also for the Big Four and their Contract and Finance Company, if only because the UP had its defenders, including General Sherman’s brother, and they might well broaden any investigation.53

So, on April 9, Dodge met with Huntington in Washington. Both companies had reason to compromise, at once. Huntington made the initial move. The CP would buy the UP track between Promontory Summit and Ogden for its own use. “I offered them $4 million,” he later asserted. Huntington coupled the offer with a threat: if the UP refused, the CP would build its own track into Ogden. Dodge argued but eventually gave in.

The two men agreed that the roads would meet in or near Ogden. That evening, in a night session, the Congress that had created the race to begin with, finally voted to end it. A joint resolution said, “The common terminus of the Union Pacific and the Central Pacific railroads shall be at or near Ogden, and the Union Pacific Railroad Company shall build, and the Central Pacific Railroad Company shall pay for and own, the railroad from the terminus aforesaid to Promontory Summit, at which the rails shall meet and connect and form one continuous line.”54

The race was over. Who could say who won? Generally, the men involved breathed a sigh of relief Charlie Crocker spoke for most of them. He had been suffering from insomnia for months, and he later said, “When Huntington telegraphed me that he had fixed matters with the Union Pacific, and that we were to meet on the summit of Promontory, I was out at the front, and went to bed that night and slept like a child.”55

Of all the people to speak for the UP, Silas Seymour, the interfering engineer, was the least likely. But, wandering out to the end of track west of Corinne a week later, he paused to contemplate how much had been accomplished. Exactly a year earlier, he had watched Durant pound in the last spike at Sherman Summit, in the Black Hills in eastern Wyoming. Since then the UP had advanced 519 miles through desert and mountains. Seymour marveled, “Nothing like it in the world.”56

When Lewis Clement, who had so much to do with it, heard the news, he wrote his friend and CP surveyor Butler Ives, and signed off with a wonderfully perfect line: he said he was glad to contemplate “the bond of iron which is to hold our glorious country in one eternal union.”57

* Mormon crews were also grading, for both companies, but the author has seen no account of their going after each other, or of Chinese or Irish going after them.

* In Europe in World War II, American GIs used their hand grenades, or dynamite charges, to blast frozen earth apart so that they could dig foxholes.