Understand why people migrate

Understand why people migrate

Locate and use U.S. immigration and naturalization records

Locate and use U.S. immigration and naturalization records

Locate and access Canadian immigration records

Locate and access Canadian immigration records

Locate and access Australian immigration records

Locate and access Australian immigration records

Use strategies for determining your ancestor’s ship

Use strategies for determining your ancestor’s ship

Use other strategies for determining your ancestor’s place of origin

Use other strategies for determining your ancestor’s place of origin

Expand your family’s story by tracing their migrations

Expand your family’s story by tracing their migrations

Understand the naturalization process and work with those documents

Understand the naturalization process and work with those documents

Let’s step back for a moment and look how far you’ve come. You’ve discovered that there are literally hundreds of different record types that may contain information of value in documenting your forebears’ lives. You have built a strong foundation for researching your family history, and you’ve learned how to examine and analyze the evidence that you uncovered along the way.

You’ve learned a great deal about your family so far by locating and examining home sources, vital records, and civil records. Chapter 6 has made you aware of all the types of census records available and what they include. You’ve delved into many of the advanced record types, including will and probate files, newspapers, obituaries, military records, and land and property records.

You now also know how important it is to place your family into context, to conduct scholarly research, to analyze every piece of evidence you uncover, and to properly document your source materials.

This chapter discusses some important documents that help you trace your ancestors’ migrations. It presents successful methodologies for locating records of emigration, immigration, and naturalization and for evaluating their content. Working with these documents will provide evidence about your ancestors’ movements. In the process, you will want to study history and discover the reasons for leaving one place and settling in another. A variety of other, less commonly used materials will be referenced in this chapter, along with recommendations for where to locate them and how to incorporate their contents into your family research and documentation.

Since the dawn of time, it is a natural state of affairs for all creatures to migrate from place to place in order to survive. It is the natural order of things, and humankind is no different. People have moved from one place to another for a variety of reasons, sometimes moving multiple times during their lives until they found a place that suited them. While there are many reasons for moving from one place to another, the following are some of the principal motivations:

• Establishing a Family People establish relationships with one another and pair up. This generally involves setting up a residence of their own, and that may involve one or both people moving to another place. As their families grow, they may need to find another residence, or they may migrate to another location where they can better provide for their family.

• Accompanying or Following Family and Friends Many people accompanied or followed other family members or friends who moved somewhere else. The lure of employment opportunities, better living conditions, and political and religious freedom is often irresistible.

• Adoption Adoption forces the movement of the adoptee from one place to another without his or her control. Single-child and multiple-sibling adoptions have been common, especially when one or both parents died. The Orphan Trains carried children from across the United States and placed as many as 150,000 to 200,000 children in new homes in 47 states, Canada, and South America. Orphaned and indigent children were transported from Britain and Ireland to Canada and Australia for adoption at various times. And during World War II, children from Britain, Holland, Belgium, and other countries were often evacuated to relatives or through social agencies to other locations in order to protect them.

• Slavery Slave trade was responsible for destroying families and entire communities, and for the forced relocation of hundreds of thousands of persons over the ages. Human trafficking removed people from Africa to the New World, and then from place to place as a result of sale, barter, kidnapping, and theft. Invading Spanish conquerors enslaved native peoples of the Americas, and substantial numbers also were transported back to Europe as curiosities and as victims of enforced servitude.

• Forced Relocation of Native Americans Native American tribes were often perceived as an imminent danger to settlers and an impediment to progress. Armed conflicts between them and white settlers, and later the U.S. Army, ultimately resulted in treaties calling for the ceding of Native American lands and permanent relocation of Native Americans to parcels referred to as “reservations.” Many died in the relocation marches, such as those who were removed to the Oklahoma Territory in the notorious “Trail of Tears,” and in other tribal relocations.

• Natural Disasters Droughts, floods, earthquakes, volcanoes, fires, tornadoes, hurricanes, and other natural disasters are life-altering catastrophes that cause people to leave one place and move to another. Floods in Germany in 1816 and 1830, for example, displaced thousands of people. Hurricane Katrina in August 2005 and the earthquake and subsequent tsunami in Japan in March 2011 are examples of more recent natural disasters that dispersed thousands of people, many of whom may never return to their original homes.

• Drought, Crop Failure, and Famine Drought and plant diseases are common natural causes of famine; wars, land mismanagement, and other human-caused disasters also result in famine. Famine in Ireland in 1816–17 and the potato famines in 1822, 1838, and between the years 1845 and 1850 caused tens of millions of people to emigrate, particularly to the United States and Canada. Famines in France in 1750, 1774, and 1790 and then the general famine across Europe in 1848 caused French, German, Italian, Dutch, and Scandinavian people to immigrate to the United States.

• Economic Difficulties Financial problems endanger survival. The loss of employment demands a search for a new job, and people often relocate to find a new economic opportunity. Economic recessions and depressions in a geographical area are more severe, and may cause people to migrate in larger numbers. Consider the mass migrations in the United States resulting from the Great Depression of the 1930s when people relocated to any place they could find work.

• Political Turmoil or Oppression Millions of people emigrate from their native lands in search of asylum in another place in order to avoid political instability, conflict, persecution, violation of personal rights or freedoms, and other troubles.

• War War is unquestionably one of the greatest catalysts of change. Colonization, land hunger, economic advantage, ideological and social disagreements, armed civil conflicts and military actions, and the disruption and destruction they cause have long been a primary incentive for migration, relocation, and evacuation. Residents of a war-torn area may seek refuge in other locations, never to return. Military personnel and their families may be forced to relocate. A soldier, in the course of service, may also travel to areas to which he or she may later choose to relocate.

• Religious or Ethnic Persecution One overwhelming reason for the migration by our ancestors was their desire to live in freedom, to practice their religious beliefs without persecution, or to pursue the lifestyle of their ethnic group. The Pilgrims are an excellent example of the early settlers who emigrated from England to Holland and then to the American colonies. In the 20th century, the emigration of Jews and other persecuted peoples from Continental Europe to Britain, the United States, Australia, South America, and Israel provides vivid examples of persons fleeing persecution.

• Criminal Incarceration/Deportation Criminals, debtors, and political dissidents were transported to colonial settlements to eliminate them from society and serve sentences of hard labor. Others were offered the option of relocating to a colony rather than face execution or prolonged imprisonment in their homeland.

• Primogenitor or Ultimogenitor It was common in the Middle Ages (and later) for the eldest son to inherit most or all property on the death of his father. In laws or societal rules, the eldest son could then allow his mother and other siblings to remain or he could force them to leave. In some places, a separate custom called borough-English or ultimogeniture required that the youngest son inherit all the property. In either case, sisters were typically married off and other brothers were encouraged to leave and fend for themselves or become indentured apprentices or servants.

These reasons cannot possibly encompass the universe of factors that influenced our ancestors to make a move. However, placing your own ancestors into context goes a long way toward understanding their motivations. One of my favorite reference websites for a chronological representation of historical events is the Timelines of History website at http://timelines.ws. You can also use your favorite web browser to search for historical timelines for specific geographical areas. Simply enter the word timeline and the name of the state, province, or country for which you want to find a timeline. Chronological timeline information can help add rich context to your understanding of your ancestors’ lives.

The desire to trace one’s ancestors back to a place of origin is one of the principal motivations for family history researchers. Many of us will spend our entire genealogical research career investigating family members in the country in which they settled, and that is also commonly the same one in which we live and with which we are familiar. However, the impetus to continue the quest backward to our ancestors’ native land(s) will take many of us on another, more rigorous research trek.

Placing your ancestor in geographical and historical context becomes a research imperative when you begin retracing his or her migration path across an ocean and back to the place of birth. It is essential that you consider the country and place of origin and the destination country, their geographies, the social and historical environments at the time, and the motivations for both leaving the old country and choosing to go to a particular location in the new country. For many of us, the knowledge of the place of our family’s origin has been lost to time and we will have to use all sorts of clues to reconnect a migration path backward. The pointers we’ll use may include letters, photographs, books, family stories or traditions, immigration records, passenger lists, naturalization documents, census records, passports and visas, and a host of other primary and secondary information. This may seem a daunting task, but making that connection is certainly one of the most rewarding and insightful experiences you can imagine.

We earlier discussed some of the motivating factors that compelled our ancestors and their family members to migrate to a new place. Deciding to undertake a move of this magnitude was no small matter; it took a great deal of courage and planning, and it usually meant leaving family, friends, and everything familiar forever. Our ancestors were literally risking everything, including their lives. Under extreme circumstances, some people fled their homes with little preparation. However, a majority of the emigrants left their ancestral home place for another part of the world with some plan for where they would go and what they would do to survive when they arrived. These people were courageous and often endured terrible conditions in order to make a new life for themselves and their families.

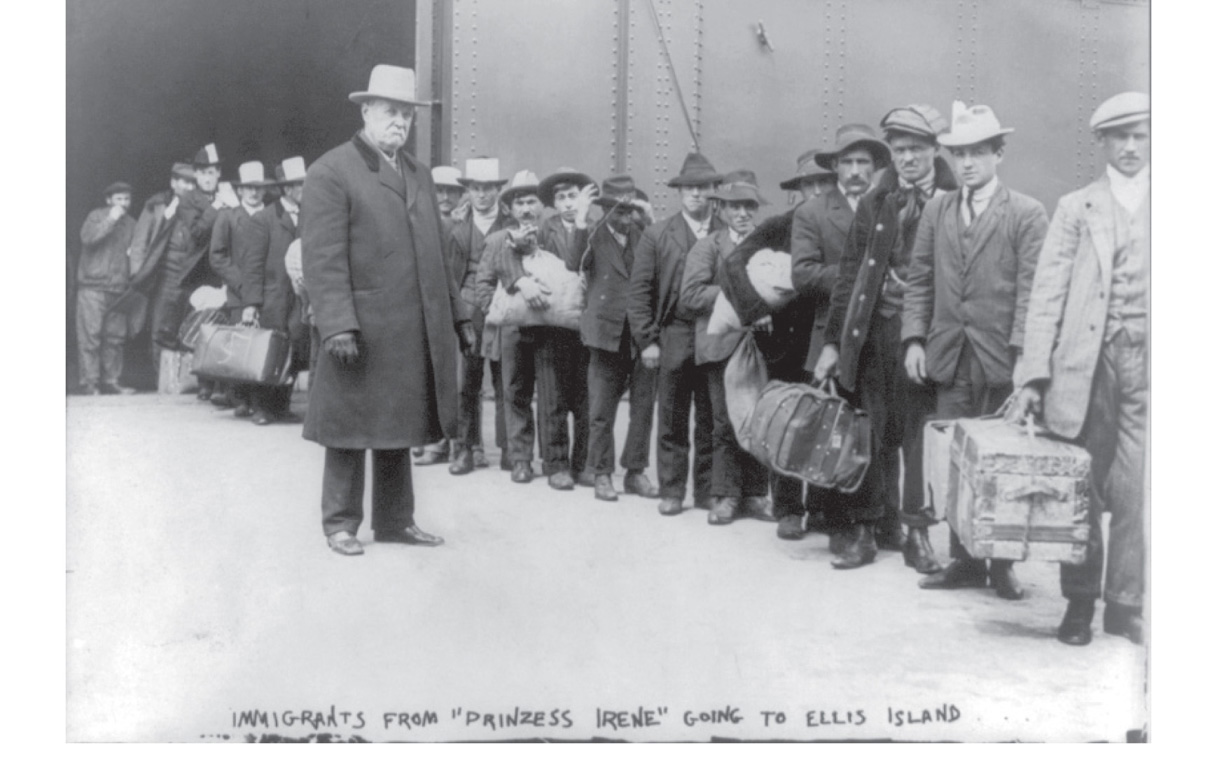

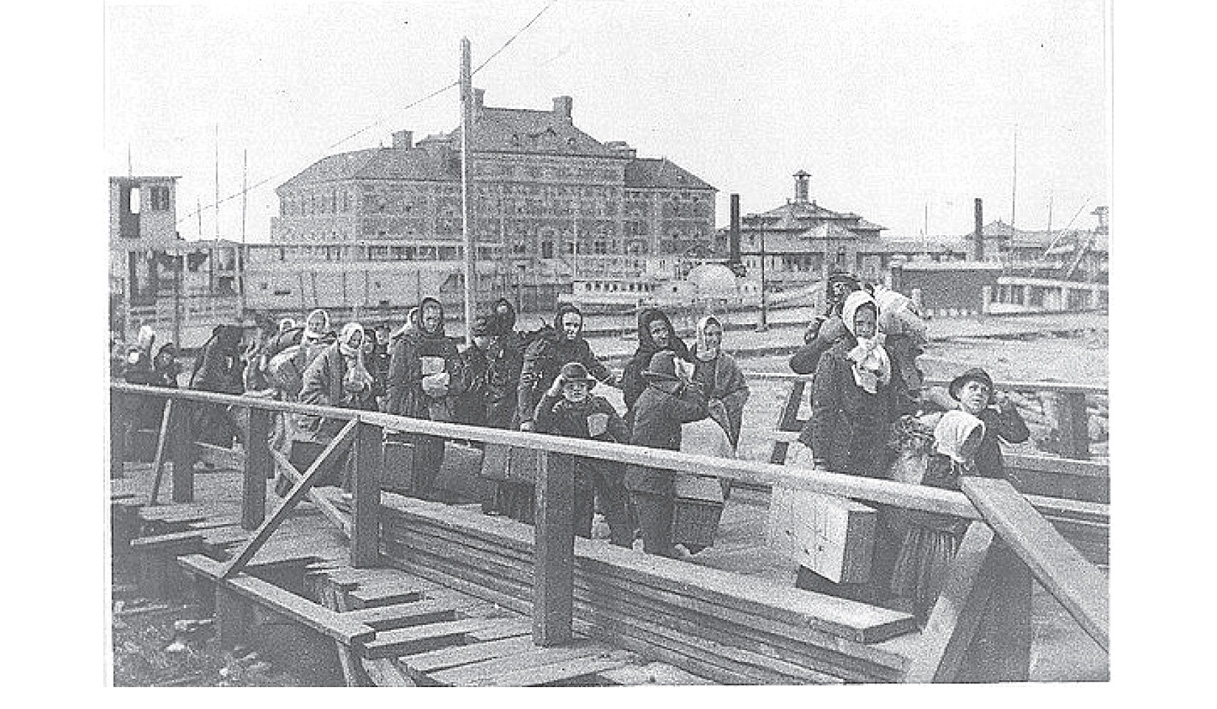

For most of us, our immigrant ancestors arrived in ships. One of the most familiar images to many immigrants or first-generation Americans is that of the immigration processing station Ellis Island. Millions of people, such as those shown in Figure 10-1, arrived there between 1 January 1892 and 12 November 1954. These immigrants may have left their hometowns on foot, in wagons and carts, in canal boats, and even on trains, to reach a seaport from which they departed to cross an ocean. Millions upon millions of people traveled in ships and, depending on the time period, the type of ships on which they traveled determined the duration of the voyage and the living conditions in which they traveled. It was not until well into the 20th century that people emigrated via airplane and, when they began doing so, many of the records we seek were no longer created—in particular, the ships’ passenger lists and manifests.

FIGURE 10-1 Immigrants arriving from Italy at Ellis Island in New York, ca. 1911

You will find that immigration and naturalization are inextricably linked together, not just because one event occurred before the other but also because, for your ancestors to become naturalized citizens in the new country, proof of when, where, and how they arrived there was required. We’re going to concentrate on immigration to the United States and the naturalization process to become an American citizen. However, we also will explore the wealth of records concerning immigration to Canada and Australia from Britain and Ireland and resources for tracing ships from other countries to these destinations as well.

Many migration routes have been used throughout the centuries. You will need to study history to determine the events taking place in their location origin at that particular time. The available modes of transportation and the migration paths used at the time played very significant roles in migrations. This is true not only in the place of origin but also at the destination. Once your ancestors arrived at a point in the new country, they had to travel overland. This may have been done on foot, on horseback, in a wagon or stagecoach, a boat, a train, an automobile or motor coach, an airplane, or a combination of any of these.

There are many excellent websites about emigration for your review, depending on your area of interest. They include the following:

• German emigration to the United States at

http://spartacus-educational.com/USAEgermany.htm

• Irish emigration to the United States at

http://spartacus-educational.com/USAEireland.htm

• Italian emigration to the United States at

http://spartacus-educational.com/USAEitaly.htm

• Russian emigration to the United States at

http://spartacus-educational.com/USAErussia.htm

• Swedish emigration to the United States at

http://spartacus-educational.com/USAEsweden.htm

• Immigrants to Canada at http://jubilation.uwaterloo.ca/~marj/genealogy/thevoyage.html

• Museum Victoria’s “Immigration to Victoria [Australia] - A Timeline” at

http://museumvictoria.com.au/discoverycentre/websites-mini/immigration-timeline

For United States research, I have two favorite collections of historical maps online. The first is the Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection at the University of Texas at Austin, located at http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps. Once at that site, click the first half of the link labeled “Maps of The United States including National Parks and Monuments,” and then click the link labeled “Historical Maps of the United States.” The menu bar near the top of the page contains links to several interesting groups of maps on this page, including “Exploration and Settlement” and “Territorial Growth,” excellent references for migration routes. Also on this page, under the section labeled “Later Historical Maps,” are a number of maps compiled from the 1870 U.S. federal census that show concentrations of population settlements of Chinese, English and Welsh, British American, German, Irish, and Swedish and Norwegian people. All of these were prepared in 1872.

My other favorite collection is the David Rumsey Map Collection at http://www.davidrumsey.com. It includes thousands of maps of North America and South America, and historic maps of Europe, Asia, Africa, and other places around the world. You have a choice of a number of viewer tools with which to view the maps. The LUNA browser is simple to use and provides splendid viewing results. It runs in the Internet Explorer, Firefox, Safari, and Google Chrome browsers. The Insight Java Client, which requires a free download of software that installs on your computer, is another excellent viewing option. This collection is searchable in a variety of ways and the images are exceptionally good. (You may need to turn off any pop-up blocker software on your computer in order to access the map images.) Of particular interest is the ability to use Google Earth and Google Maps to overlay in particular areas. Specific historic maps have been interlinked with these two Google facilities and provide excellent geographical context for your research.

Passenger lists, also referred to as “passenger manifests,” will vary in format and content, depending on who created them, why they were created, the time period, and other factors. For example, persons transported in bondage from England—that is, prisoners transported to a colony as punishment and/or to permanently get rid of them—may be documented in court records in the country of origin. The person may also be listed on a prisoner ship’s records. In other places, there may be no immigration lists available at the destination location but there may well be emigration lists and/or ships’ manifests at the point of departure.

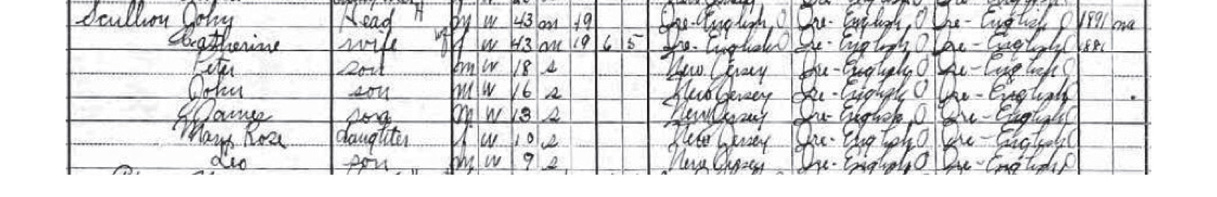

In addition, and perhaps most important of all, it is imperative to remember that you must always look for the obvious records and, in the event that you can’t find those, investigate the possibilities that there may be alternative record types that can help document the migration. For example, if there are no ships’ passenger lists, look for both emigration records from the country of origin and immigration and/or naturalization records in the destination country to document the arrival. Also, in the United States, you can use the decennial federal census records starting in 1850 to help document and trace your immigrant ancestors. For example, the 1850 census was the first to ask for the place of birth (State, Territory, Country). The 1880 census asked for the place of birth of each person as well as of his/her father and mother. The 1900, 1910, 1920, and 1930 federal censuses each asked for the year of immigration and whether the person had been naturalized. The 1940 census asked for place of residence as of 1 April 1935, but it also asked for the person’s place of birth. The enumerator was instructed to ask foreign-born individuals the name of the country in which the person’s birthplace was located as of January 1, 1937, and citizenship status. (This census did not ask for the year of arrival in the United States.) Census Population Schedules for some enumerations also asked for the language spoken, or “mother tongue,” and that can help lead you to the place of origin. These records can therefore be the bonanza you need in the way of pointers to other records and/or can be used as alternative, supplemental, and corroborative evidence and documentation.

Figure 10-2 shows detail from the 1910 U.S. federal census for the John Scullion family in Patterson Ward 8, District 0138, in Passaic County, New Jersey. John and his wife, Catherine, were born in Ireland. Their four sons and one daughter living were born in New Jersey. To the right of these birth locations is a two-column set of critical information for your search. The year of arrival in the United States is listed in the first column. You can see that John arrived in 1891, and it appears that Catherine arrived in 1881. (Other censuses may show that Catherine arrived in other years, therefore presenting a discrepancy that needs to be addressed. You may therefore need to check ships’ passenger lists and naturalization records.)

FIGURE 10-2 1910 U.S. federal census detail showing places of birth, arrival year, and naturalization status

In the next column for John is a notation “na.” This indicates that he has been naturalized. That should be a clue to begin tracing his naturalization records. It appears that his wife was not naturalized by 1910. Subsequent searches of the 1920 and 1930 censuses show that Catherine had not become a naturalized citizen.

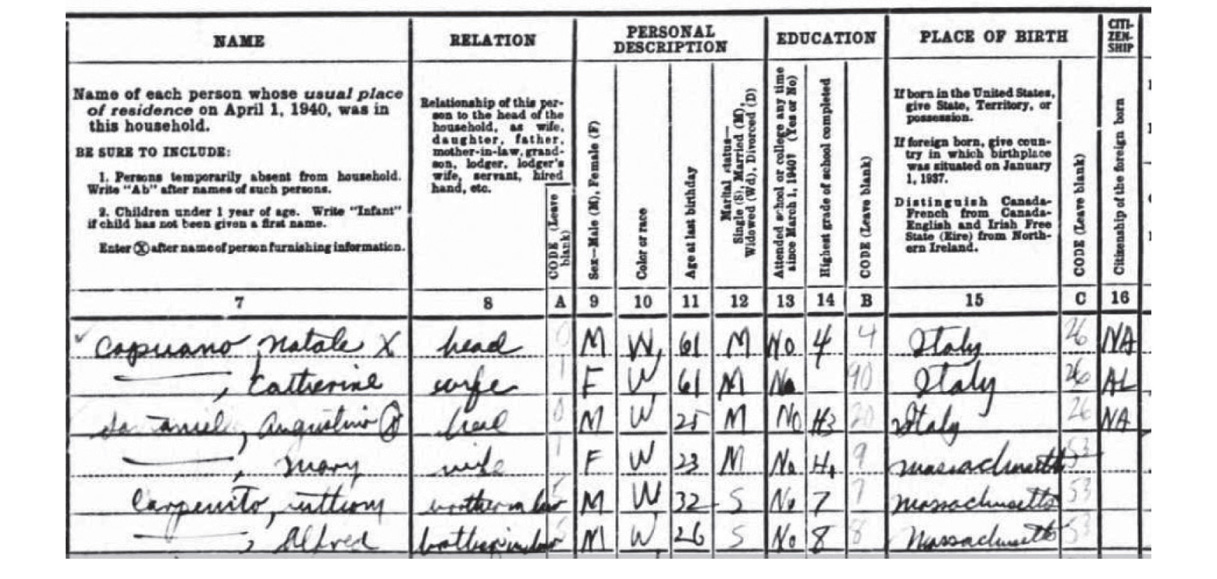

Figure 10-3 shows detail from a 1940 census in Ward 3, Boston, in Suffolk County, Massachusetts. Natale Capuano and his wife, Catherine, are shown as born in Italy. The code NA in the Citizenship column for Mr. Capuano indicates that he has been naturalized, but the code AL in the column for Mrs. Capuano indicates that she is still an alien. For the next couple, Augustino and Mary Santanielli, the census shows that he was born in Italy and has been naturalized and that she was native-born in Massachusetts. The next two people, Anthony and Alfred Carpenito, are shown as brothers-in-law of Augustino Santanielli and that they were born in Massachusetts.

FIGURE 10-3 1940 U.S. federal census detailing country of birth and naturalization status

Let’s look at the United States and ships’ passenger arrival lists that you may want to research and examine. In order to understand what is available, we need to briefly examine the history of these records.

Prior to the Revolutionary War in the American colonies, there was no formal attempt in most areas to require passenger arrival lists. Indeed, any requirements were instituted by the colonies themselves as they had control over their own affairs. Because the 13 colonies were, in fact, British, and close to 80 percent of the white immigrants arriving before 1790 came from England or from other British-governed countries, there was little or no need to record the arrivals. Any documentation about passenger movement was created or maintained by the ships’ owners and operators; the colonial governments maintained any information concerning shipping commerce. Their primary concerns were the regulation and taxation of incoming and outgoing goods. Government officials had little interest in passenger arrivals other than those of Crown prisoners and indentured servants.

Pennsylvania was an exception in that it recorded the arrival of Continental Europeans at the Port of Philadelphia, primarily German, French, Dutch, and Swiss, in the years 1727–1744, 1746–1756, 1761, 1763–1775, and 1785–1808. Prior to the American Revolution, British subjects arriving at the port were not recorded because the colonists were also considered British subjects. There were essentially three lists compiled, consisting of: 1) the ship’s captain’s list, made on board the ship, of names from the passenger manifest; 2) lists of oaths of allegiance to the British king that were signed by all males over the age of 16 who could walk to the local magistrate at the port of arrival; and 3) lists of the signers of the oath of fidelity and abjuration, a renunciation of any claims to the throne of England by “pretenders,” also signed by males over the age of 16 who could walk to the courthouse. One estimate is that only about two-fifths of the ships’ passengers actually signed these oaths, but not all of the ledgers and documents have survived. These passenger lists and related documents have been microfilmed and are in the possession of the Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission. You can learn more about these documents at http://www.portal.state.pa.us/portal/server.pt/community/naturalization_and_immigration/3851/ships’_passenger_lists/387311.

If you are seeking information about early immigrant arrivals in the other colonies, it is important to look for alternative records, as previously mentioned, such as “lists of departure” in the original country. Some of these are in national archives, local archives or libraries, or in local government record repositories near the port of departure. (In Spain and Portugal, there are extensive archival holdings relating to shipping and passenger movements that trace back in some cases into the 1300s, and hence we have a solid historical record of much of the global exploration from those periods.) Histories of individual colonies and settlements may also provide you with information about arrivals of individuals or families and their participation in the community affairs. The individual state archives may have other records to help document the arrival of foreign-born individuals. These might include documents concerning bounty colonists (those whose passage was paid as an incentive to settle in the colony), papers of indentured servants, or arrivals of criminal deportees. Land and property records may also provide you with clues to your ancestor’s time of arrival.

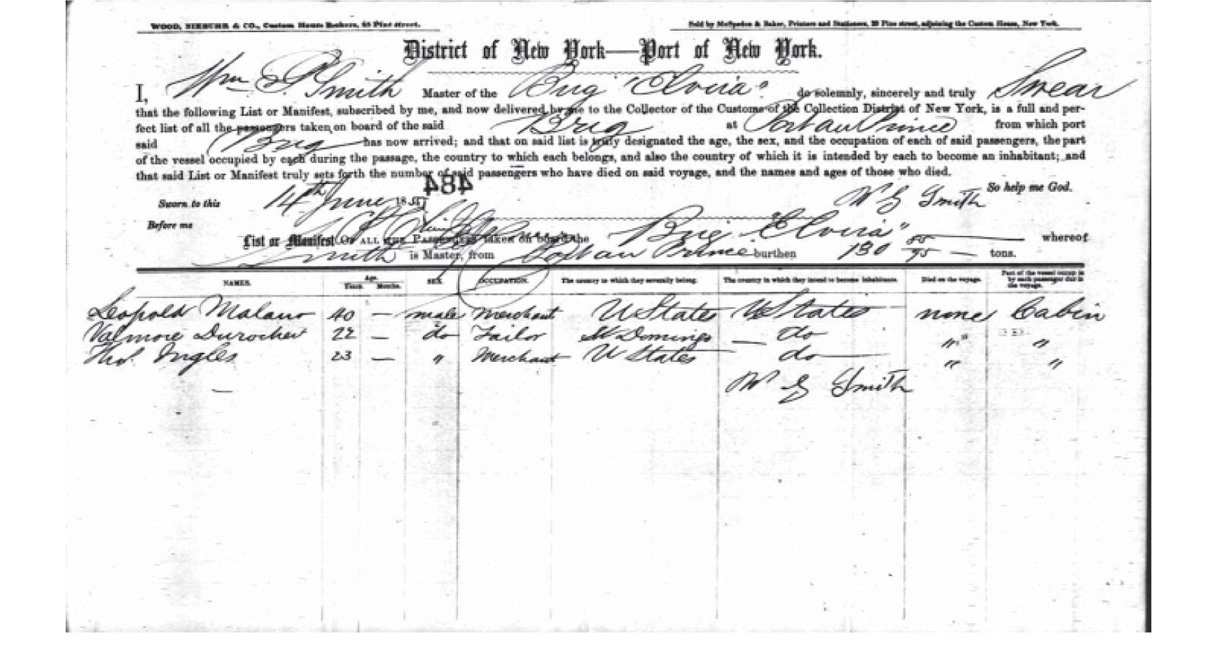

The year 1820 is a bellwether for U.S. historians and genealogists from an immigration perspective. In that year, Congress passed legislation calling for passenger lists to be filed by each ship’s master with the customs officer in the port of arrival. Manifests of goods being brought into port were already being prepared and delivered to the customs officer. However, passenger manifests were something new. These documents are sometimes referred to as the “customs passenger lists” or “customs passenger manifests.” Two copies of the passenger list, like the ones shown in Figures 10-4 and 10-5, were created either just prior to the ship sailing or onboard the ship, and listed each passenger. The ship’s master was also required to record on the list any births and deaths that occurred during the voyage. The names of members of the crew were not required until much later. On arrival at port, the ship’s master was required to deliver both copies of the document to the customs collector. The master then swore under oath that the lists were complete and correct, and then both he and the customs officer signed the documents. One copy remained with the customs collector, and the ship’s master retained the other copy. The customs officer was required to prepare a summary list of all passenger arrivals at the port on a monthly or quarterly basis and send it to the Secretary of State in Washington, D.C. The summary included the name of every vessel; the port of origin; any intermediate ports of call; the date of arrival; each respective ship’s master’s name; and the names, gender, and ages of all passengers.

FIGURE 10-4 Passenger list of the Brig Elvira, which arrived in New York on 14 June 1855

FIGURE 10-5 Manifest of the Obidense, which arrived in New York on 10 July 1910

A Congressional act passed in 1882 required that federal immigration officials record all immigrants arriving in the United States. There are lists that were produced dating from 1883 for the port of Philadelphia and from 1891 for most other ports, and these have been microfilmed by the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA). These lists include the name of the master; the name of the ship; the ports of departure and arrival (including intermediate stops); the date of arrival; the name, place of birth, last residence, age, occupation, and gender of each passenger; and any other remarks. The intermediate ports of call may be important for tracing your ancestors’ stages of migration.

The year 1891 was important to U.S. immigration and naturalization for a number of reasons. In that year, a separate federal governmental agency was formed whose purpose was specifically to oversee immigration. This was the Office of the Superintendent of Immigration, and it was a division within the Treasury Department. For the first time, this new bureau strictly oversaw immigration. As a result, the records created called for more detail.

Between 1891 and 1903, responsibility for the collection and maintenance of the forms passed through several federal departments, finally becoming the province of the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS), which was formed in 1933 as part of the Department of Labor (in 1940 transferred to the Department of Justice). The INS immigration service functions were transferred to the new U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) in 2003 as part of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS).

Standardized forms, such as the one shown in Figure 10-5, began to be used in every embarkation port around the world and were to be prepared before the departure of the ship. Therefore, any changes would have been noted prior to entry into any U.S. port. Only births, deaths, and the discovery of a stowaway would have caused the manifest to be changed en route.

Again, the forms were to be presented to the customs and immigration service officers at the port of arrival. The forms became known as Immigration Manifests or Immigration Passenger Lists. When these forms were introduced in the early 1890s, they required more information than ever before to be provided. (Please see Table 10-1.) Further columns were added in later years, all of which provide more information for our genealogical use.

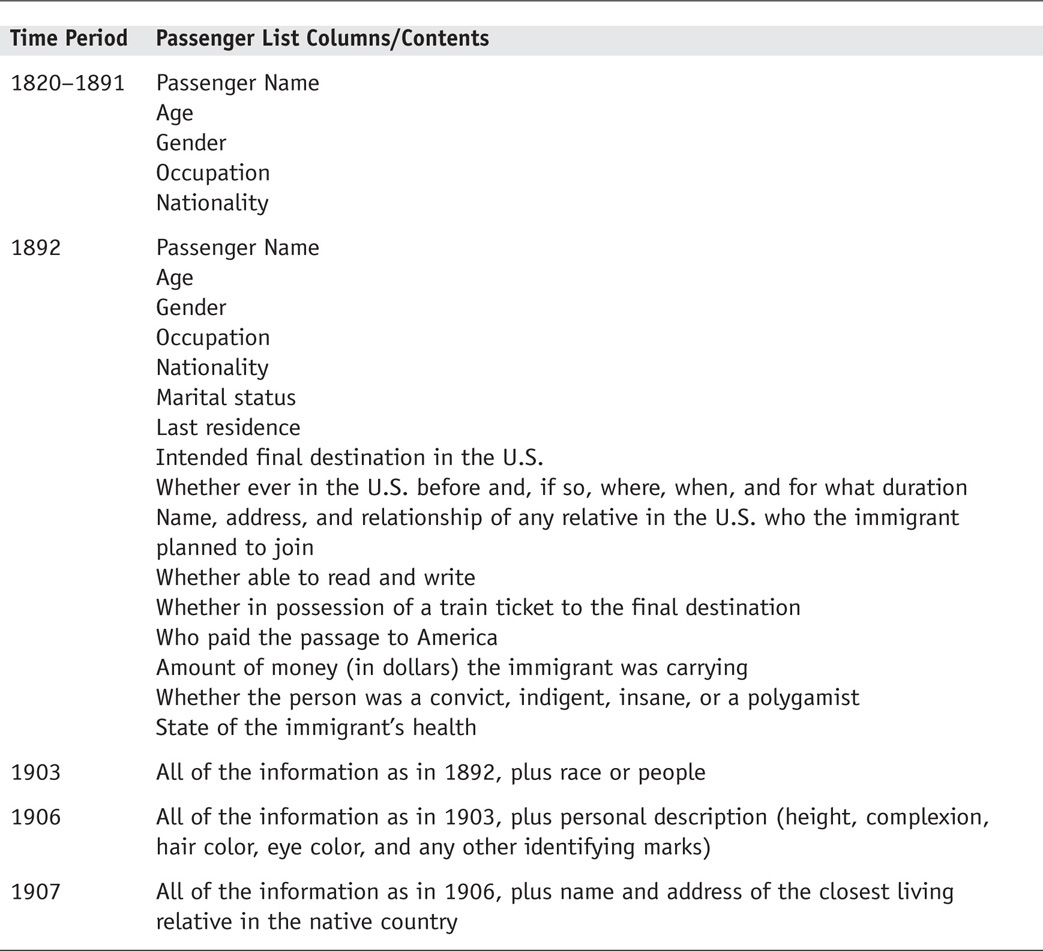

TABLE 10-1 Required Contents for Passenger Manifests Arriving in the United States

The new Bureau of Immigration formed in 1933 requested that all of the earlier passenger arrival records from all ports of arrival be sent to their office in Washington, D.C. Unfortunately, however, that was easier said than accomplished. The original documents had been stored in customs houses, courthouses, customs collectors’ homes, and other places. Some had been damaged, destroyed, or simply lost. Fortunately, a vast majority of the original customs passenger lists from 1820 to 1905 survived, as did the majority of the customs collectors’ monthly reports. These are in the possession of NARA and have been microfilmed. In fact, where the original passenger list had not survived, NARA used the customs officers’ reports as substitutes to fill in gaps in chronological sequence in the microfilmed records. While these abstracts don’t contain as much detail as the original passenger manifests, they do supply critical nominal information and other details.

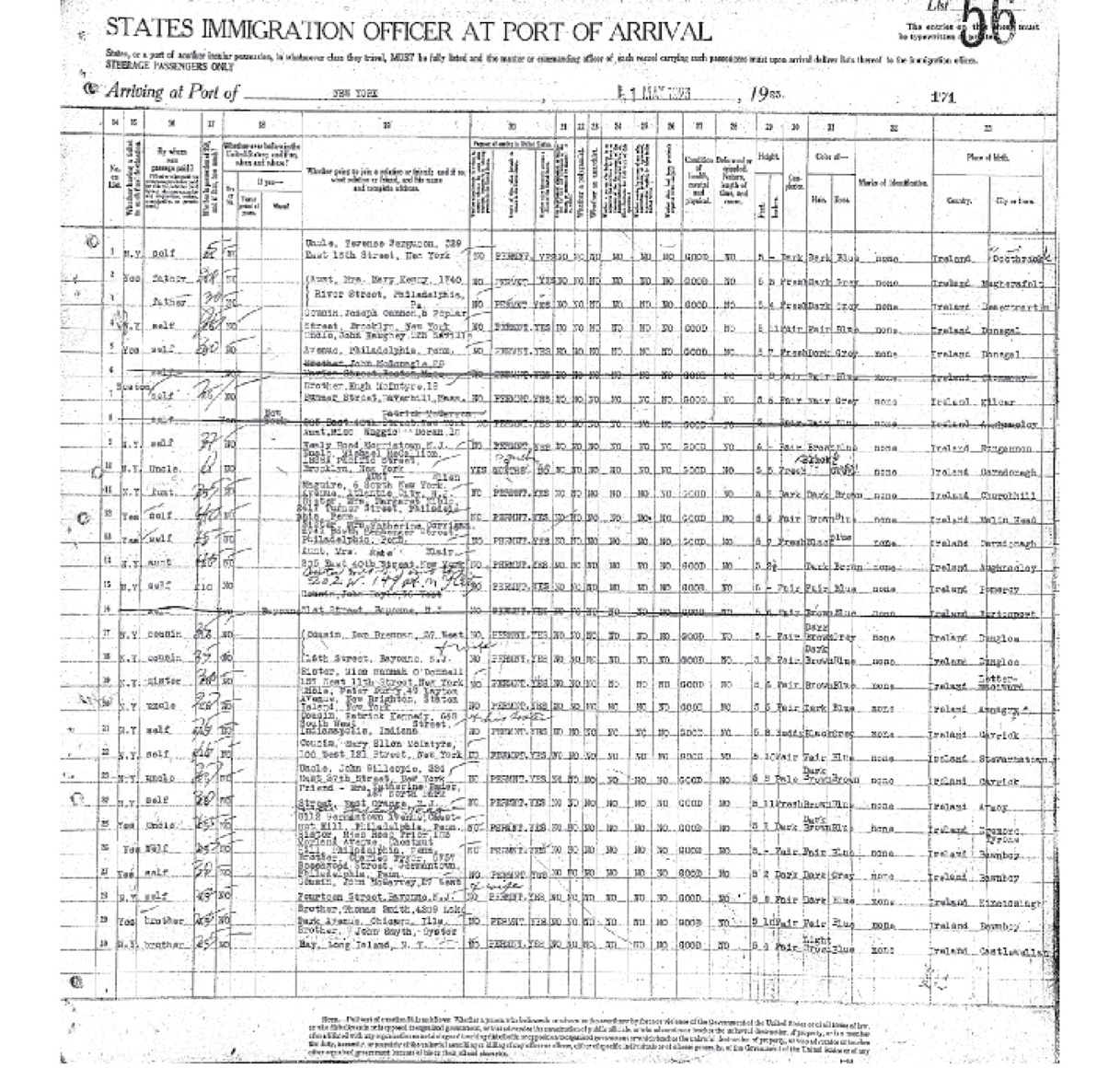

Through the 1800s and 1900s, passenger lists were prepared with more forethought to their clarity and accuracy. Many of these documents were completed using a typewriter, such as the example in Figure 10-6, which certainly makes for easier reading. However, because the typewritten passenger lists were likely prepared from other handwritten documents, the possibility of transcription and typographical error increased.

FIGURE 10-6 Page from a passenger manifest of a ship arriving in New York on 1 May 1923

For more extensive information about ships’ passenger lists and manifests, you will want to read John Philip Colletta’s definitive book, They Came in Ships: Finding Your Immigrant Ancestor’s Arrival Record, Third Edition (Ancestry Publishing, 2002), articles in The Source: A Guidebook to American Genealogy, Third Edition (Ancestry, 2006) and in the Ancestry Family History Wiki (http://www.ancestry.com/wiki/index.php?title=The_Source:_A_Guidebook_to_American_Genealogy), and Loretto D. Szucs’s definitive reference book for immigration and naturalization reference, They Became Americans: Finding Naturalization Records and Ethnic Origins (Ancestry.com, 1998).

There are any number of indexes and finding aids to these records, and the resources cited previously provide excellent guidance to help you locate these indexes. Perhaps the most definitive is the mammoth set of books by P. William Filby, the Passenger and Immigration Lists Index and the annual supplements (Gale Group, 1985 to present). These books are part of an ongoing project to index as many resources of ships’ passenger information from as many sources as possible. This work and its annual supplements may be found through libraries and archives with larger genealogical book collections. It also is available (through 2008 at this writing) at WorldVitalRecords.com (http://www.worldvitalrecords.com; search for “Passenger and Immigration Index” in the Keyword box).

NARA’s microfilm of the complete chronological set of ships’ passenger lists and/or customs officers’ reports for all U.S. ports of arrival has been digitized and indexed by Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com). FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org), at the time of this writing, is in the process of digitizing and indexing these records and placing them online. Passenger arrivals at the Ellis Island processing facility in New York, NY, between the years 1892 to 1924 have been transcribed and indexed by the Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation at http://www.libertyellisfoundation.org, and are free to search online. Information displayed on a search result record includes: first name, last name, ethnicity, last place of residence, date of arrival, age at arrival, gender, marital status, ship of travel, port of departure, and line number on which the person’s name appears on the ship’s manifest.

Although passengers arrived at about 100 different U.S. shipping ports over the centuries, most ports saw only intermittent traffic. Sometimes only a few ships with passengers would arrive in a given year. During the early years, most of the immigration traffic coming into the United States tended to be directed to one of five major ports: Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and New Orleans. Although Philadelphia had been the most popular of these ports during the colonial era, within the first two decades of federal immigration regulation, New York emerged as the preferred port of arrival. One of the reasons for this transformation was the construction of the Erie Canal, which provided faster and more economical travel inland than other forms of transportation. The canal provided an excellent migration route to upstate New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, and into the Great Lakes areas.

By 1850, more immigrants arrived in New York than in all other ports combined. By the 1850s, New York was also a major railroad hub offering access to nearly every part of the country. Because of the waves of immigrants entering the city, New York was the first port to open an immigration arrival and processing depot. Castle Garden, shown in Figure 10-7, was located at the Battery in lower Manhattan. It was the processing center for the Port of New York and was the predecessor to Ellis Island, which opened on 1 January 1892. Castle Garden was a massive stone structure originally built in 1808 as a fort. It later served as an opera house, and New York State authorities transformed it into an immigration landing and processing station beginning on 1 August 1855.

FIGURE 10-7 View of Castle Garden in New York

Castle Garden’s primary purpose was not only to receive and inspect immigrants, but also to help protect them from the thieves, swindlers, confidence men, and prostitutes who prowled the piers looking for easy marks. Inside Castle Garden, immigrants could exchange money, purchase food and railway tickets, tend to baggage, and obtain information about boarding houses and employment. More buildings were erected outside the original Castle Garden to handle the additional volume of people as immigrant arrivals increased. Brick walls were constructed to enclose the large complex. On 18 April 1890, the last immigrants were processed through Castle Garden. During these years, more than eight million immigrants had passed through Castle Garden.

Control over the immigration processing in New York shifted to the U.S. Superintendent of Immigration, and the Barge Office became an interim arrival depot for the immigrants, pending the opening of a new immigrant-processing center on Ellis Island on 1 January 1892. Immigrants such as those shown in Figure 10-8 arrived at a modern, well-organized facility where they were given physical examinations, helped with completing forms by interpreters who spoke their language, and processed efficiently through customs.

FIGURE 10-8 A group of immigrants is shown arriving at Ellis Island

On 14 June 1897, however, fire destroyed the Ellis Island facility, and with it went the administrative records of Castle Garden (1855–1890), the Barge Office (1890–1891), and Ellis Island (1890–1897). These were administrative records only, and it is believed that very few passenger list documents, if any, were lost. The passenger lists that had already been handled over Ellis Island’s years of operation to that date were perfectly safe and already in the custody of the Bureau of Customs and the Bureau of Immigration. The Ellis Island facility was reconstructed, this time using fireproof materials, and it reopened on 17 December 1900. It served as the immigration-processing site for New York until 1954. During reconstruction, immigration processing returned to the Castle Garden location, and all records produced were collected with the Ellis Island recordkeeping system. Again, you will want to research passenger arrivals at the Ellis Island Foundation site at http://www.libertyellisfoundation.org. Stephen P. Morse has developed an excellent website that can help you get past some of the limitations of the official Ellis Island Foundation site, and his site can be accessed at http://stevemorse.org. Here you will find numerous search tools for both the Castle Garden and Ellis Island immigrant arrivals.

New immigration forms were implemented at different times in different ports depending upon a number of factors, most notably who was in charge of the port at the time. Federal immigration officials began regulating many ports of arrival starting in 1891. Other ports were regulated and administered by local officers contracted by federal officials. Any lists created under the authority of the Bureau of Immigration are considered and referred to as “immigration passenger lists.” This distinguishes their content and handling from that of the customs collectors and the “customs passenger lists” and the associated processing that was used from 1820 until 1891.

Contrary to popular myth, the employees of the immigration processing centers did not arbitrarily change immigrants’ names as they arrived. You may have seen photographs of immigrants queued up for interview or inspection in which paper tags were attached to their clothing. Each tag actually bore the name of the ship on which the person had arrived and the line number on the passenger manifest on which his or her name was listed. The processing stations used these tags to facilitate the expeditious processing of persons who spoke little or no English. The tags assisted in directing the new arrivals into proper lines for processing. There also was a small army of translators available to assist in the arrival and inspection process. Many immigrants actually changed their own names prior to sailing, on arrival in the new country, or later in order to become more quickly assimilated into American society. Two of the naturalization forms that we will discuss later in this chapter and that were used in the United States at various times have included a place to indicate the name under which the person arrived in the country.

Virtually all of the later immigration passenger lists survived and were eventually acquired by NARA after its creation. As mentioned before, thousands of bound volumes of these lists (about 14,000 volumes of Ellis Island records alone) were microfilmed by NARA during the 1940s and 1950s. Since much of the project was completed comparatively early in the history of microfilming, the quality is not always good. Some estimates indicate that as much as 6 percent of the lists are difficult or impossible to read, with that number reaching as high as 15 percent for the pre-1902 lists. The source documents were destroyed after microfilming, though, making it impossible to create new digital images from the originals.

There are several sets of indexes to the ships’ passenger lists. You can begin by using indexed digital images at Ancestry.com and FamilySearch. You can use the indexes such as those produced by P. William Filby that were mentioned earlier. There may also be colonial, state, and local histories, and transcriptions in both print and on the Internet to locate ships whose port of origin and time period seem appropriate candidates to search. State archives and libraries may also hold documents that may help you locate the names and ships of arrival of your immigrant ancestors.

Don’t forget that U.S. federal census Population Schedules, too, can be a boon as part of your research strategy. For example, the following years’ U.S. federal census Population Schedules contain important clues:

• 1880 Nativity columns ask for place of birth for the named person on the census form, as well as his or her parents.

• 1885 This census taken for five states and territories (Colorado, Dakota Territory, Florida, Nebraska, and New Mexico) includes Nativity columns that ask for place of birth for the named person on the census form, as well as his or her parents.

• 1890 Nativity information is once again requested for the named person on the census form, as well as his or her parents. The number of years in the United States, whether naturalized, and whether naturalization papers have been taken out are also requested. If English was not spoken, the language or dialect spoken was requested.

• 1900 Nativity information is again requested. In addition, the year of immigration is requested, as well as number of years in the United States and status of naturalization.

• 1910 Nativity information is again requested. In addition, the year of immigration, whether naturalized, and language spoken if not English are included.

• 1920 Year of immigration, naturalization status, and year of naturalization are requested. Place of birth and mother tongue are requested for the named person on the census and his or her parents.

• 1930 Place of birth of named person on census and of parents are requested, as well as language spoken in home before coming to the United States. Year of immigration and naturalization status are included.

• 1940 Place of birth of each individual and the citizenship status are requested.

All of these years’ census Population Schedules can provide pointers to the person’s nativity. The census Population Schedules of 1910, 1920, 1930, and the surviving fragments of the 1890 census, requested language spoken or “mother tongue.” A response of “Yiddish” would point to a Jewish background, and a reply such as “Polish,” “French,” or “Urdu” would indicate another national or ethnic origin. Remember that multiple languages could have been spoken by different groups in a single country of origin.

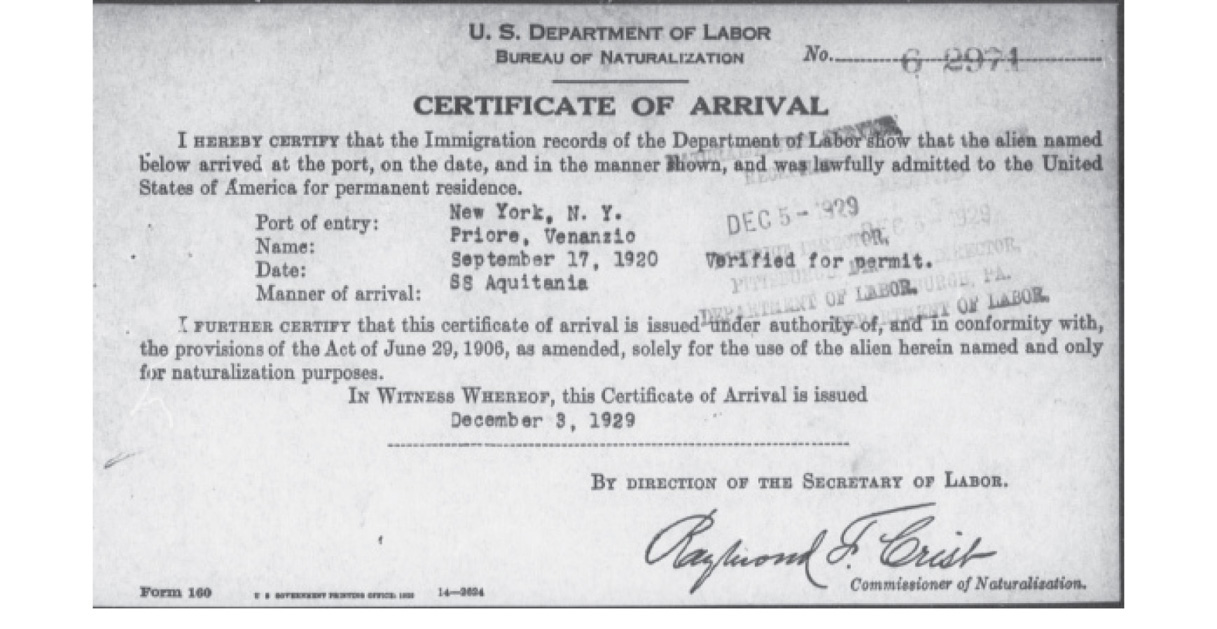

Naturalization documents, which we will discuss later in the chapter, include the date of arrival, port of arrival, and name of the ship on which the person arrived.

If you are unsure of the ship on which your ancestor arrived, it is possible to use other clues such as language, place of birth, or spelling of the surname to help narrow your search. If you have a good idea of the country of origin, you may be able to use microfilmed or digitized newspapers and read the shipping news. Ships’ arrivals, name of the port of origin, intermediate ports of call, and shipping company can help you avoid having to read every entry for every ship in a given year. In addition, by identifying the names of shipping lines arriving from your ancestor’s country of origin, you may also be able to locate ships’ manifests created and filed on the other side of the ocean.

The Immigrant Ships Transcribers Guild (ISTG) at http://www.immigrantships.net is an all-volunteer effort and is making great strides in locating, accessing, and producing accurate transcriptions of ships’ passenger lists and manifests from the 1600s to the 1900s from all over the globe.

A passport is an official document issued by the government of a country to one of its residents that certifies that person’s identity and citizenship. It entitles them to travel under that country’s protection in a foreign country through diplomatic agreements. A visa is an endorsement of a passport by a foreign country that allows the holder to enter, leave, or stay in a country for a specific period of time. An authorized representative official or agency of that specific country issues a visa. There may be specific conditions applied to a visa, such as requirements for vaccinations.

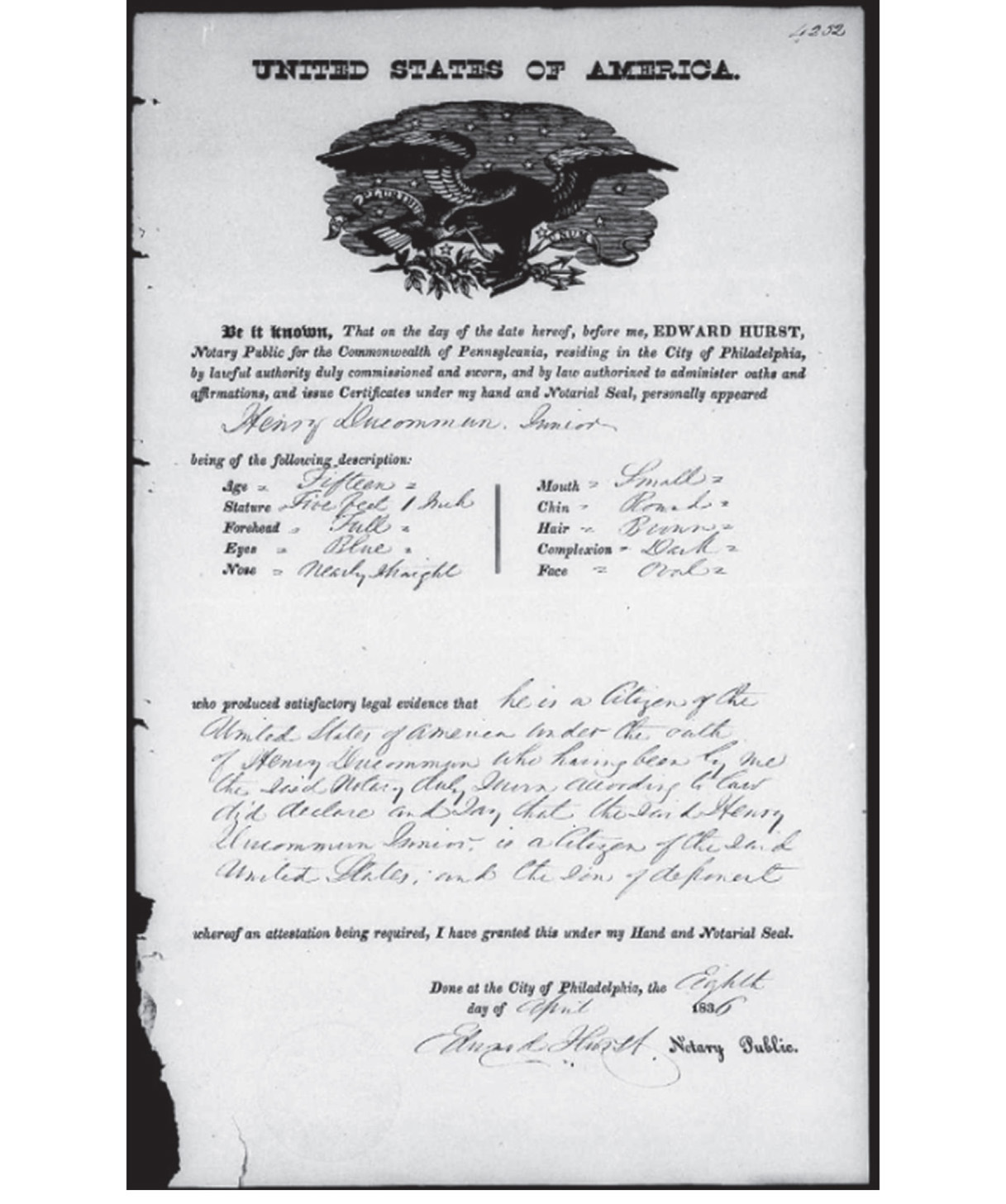

Until 1775, citizens in the 13 American colonies who traveled to foreign countries used British passports since they were, in fact, British subjects. The early American passports were issued by consular officials during the American Revolution, between 1775 and 1783, and were valid for up to six months. There was no passport requirement in the new nation between 1783 and the 1787, at which time Congress approved legislation establishing the Department of Foreign Affairs on 21 July 1789 and George Washington signed it into law on 27 July 1789. This was the first federal agency created under the new U.S. Constitution. The name was later changed to the Department of State. The passports created in up to the mid-19th century were issued by the Department of State as well as by states, certain cities, and notaries public. It was not until 1856 that Congress legislated that the Department of State was the exclusive authority that could issue and regulate passports.

Different passport applications were used over time. Early passports, like the one shown in Figure 10-9, were handwritten documents using different wordings, and physical descriptions were included. Preprinted forms were later introduced to standardize the verbiage. By 1888, there were separate application forms for native citizens, naturalized citizens, and derivative citizens (wives who became citizens through their husband’s naturalization and children who became citizens through their father’s naturalization). A husband and wife, along with their children, were frequently included on the same application form and passport.

FIGURE 10-9 This handwritten passport application was generated by a notary public in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on 8 April 1836 for Henry Ducommon, Junior.

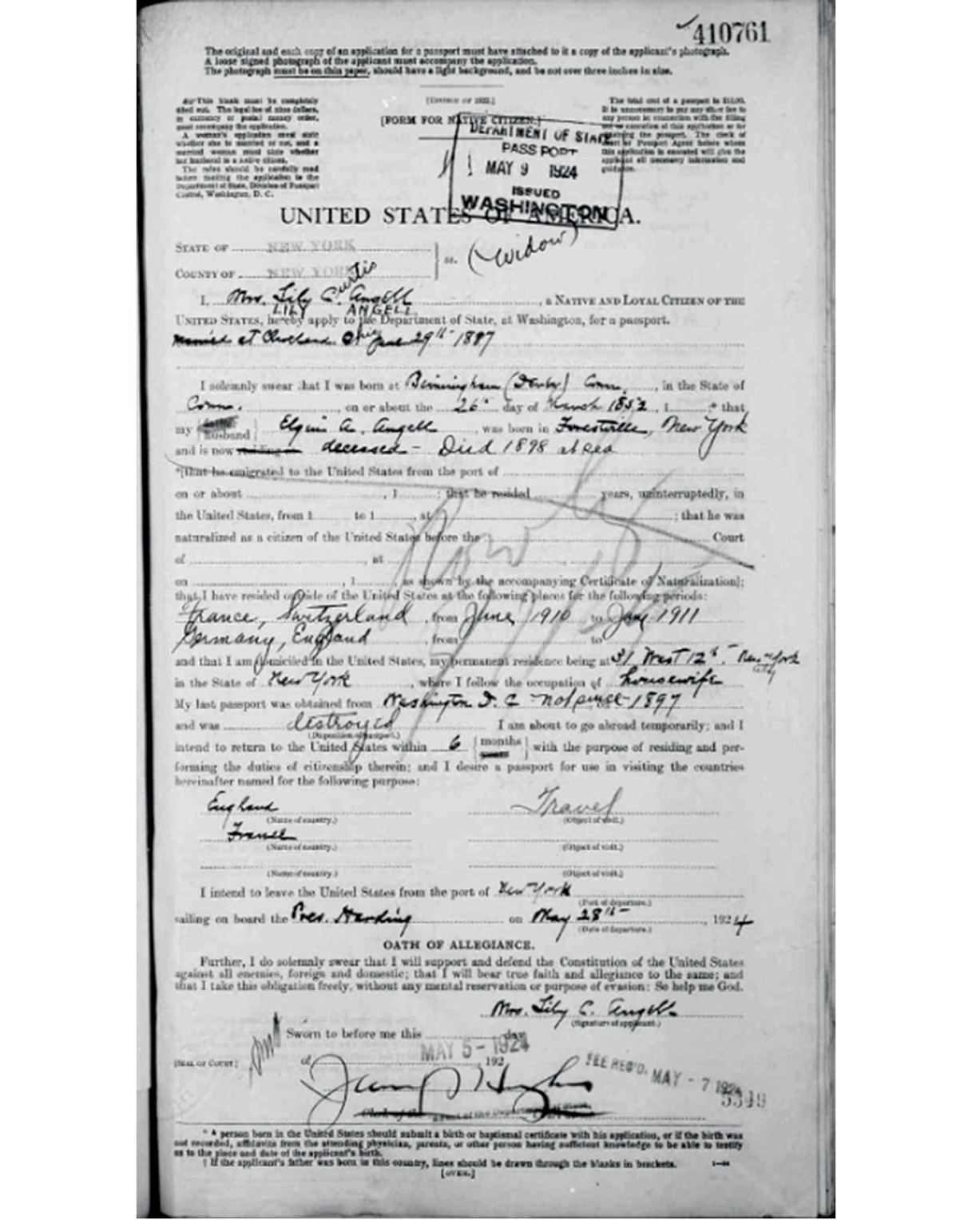

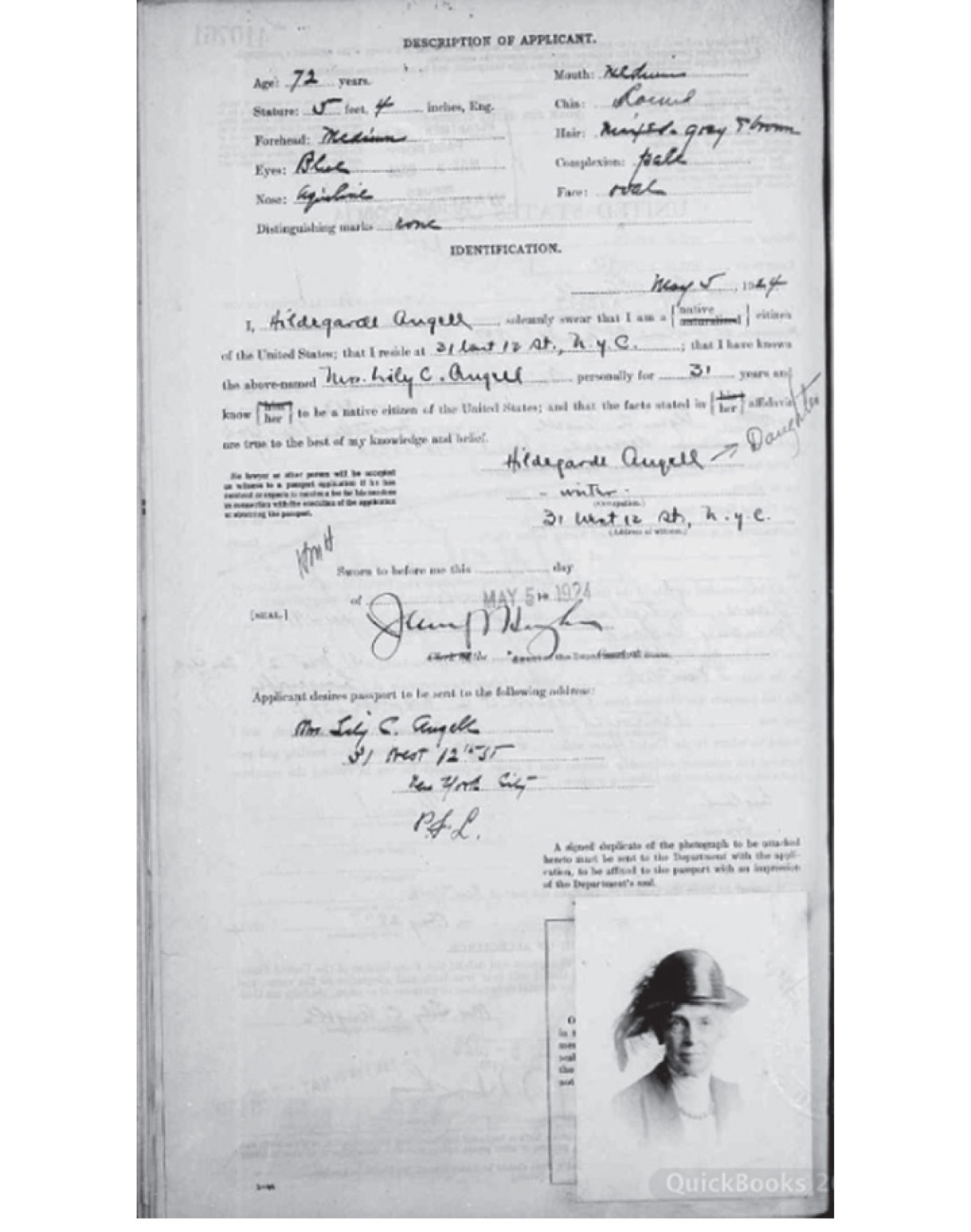

Still later forms may also have included multiple individuals; a photograph of the applicant(s) was required. As you can see, not all of the information may be consistent for all applicants at all periods. Likewise, there may be additional information written on the form by the applicant or the reviewing officials. Other supporting documents such as letters and signed affidavits may have been submitted with the application and may be part of the individual’s application file. Because these may include valuable information, it is therefore important to personally view the image of the application and any accompanying documents and determine what documentary content exists in the file. Figures 10-10 and 10-11 show both sides of an application from 1924, including a written physical description and a photograph. It provides her name, birthdate, birthplace, and address in New York, New York; informs us that her husband died at sea in 1898 and that she has lived abroad; and states that she plans to visit England and France and will sail on the President Harding.

FIGURE 10-10 Page 1 of the passport application of Mrs. Lily Curtis Angell

FIGURE 10-11 Page 2 of the passport application of Mrs. Lily Curtis Angell listing her physical description and including a photograph

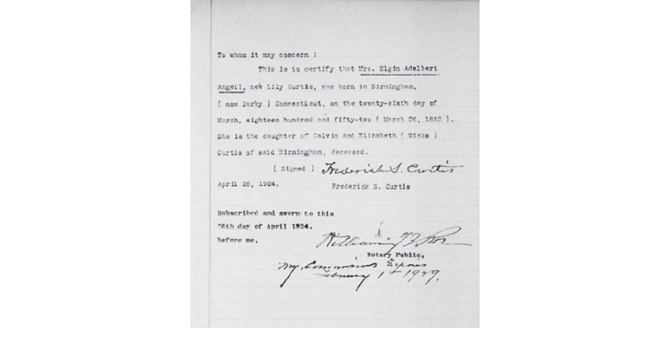

In addition, an accompanying document is a signed and notarized affidavit (shown in Figure 10-12). It provides the invaluable information of the woman’s maiden name, her date and place of birth, and the names of her parents.

FIGURE 10-12 Affidavit accompanying the passport application of Mrs. Lily Curtis Angell

The U.S. passport applications for 1795 to 1925 were microfilmed by NARA (series M1372 and M1490) and these are now digitized and accessible online. Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com) provides access to the images and searchable name indexes. FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org) has digitized the images and placed them online but, at the time of this writing, these have not yet been indexed. They can be browsed by microfilm roll, by date range, and by certificate number (where present).

Library and Archives Canada (LAC), at http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca, provides its content in both English and French. Here you will find a wealth of information for your research. On the main page, click the Genealogy & Family History link, which opens a page from which you can search any of the databases related to genealogy. You can also view the list of all the available databases. Click a link and explore the available information.

Immigration passenger lists were not required in Canada until 1865. The originals from that time from 1865 to 1922 are held by the Library and Archives Canada (LAC). A searchable database of those passenger lists is available at http://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/immigration/immigration-records/passenger-lists/passenger-lists-1865-1922/Pages/introduction.aspx. The images have also have been digitized at Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com) and Ancestry.ca (http://www.ancestry.ca). The LAC site at http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca is an excellent site at which you can learn more about the history and context of these records. FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org) has a searchable database of digitized images of Canada Passenger Lists, 1881 to 1922.

Another website with many links is Immigrants to Canada, located at http://jubilation.uwaterloo.ca/~marj/genealogy/thevoyage.html. Included are scores of links, including compilations of ships for specific years, written/transcribed accounts describing the voyages, emigrant handbooks, extracts from government immigration reports of the 19th century, and many, many nationalities’ emigration/immigration website links. Don’t miss this one. Figure 10-13 shows an example from 1934.

FIGURE 10-13 Canadian passenger list from 1934

Please note that records from 1 January 1936 are still in the custody of Citizenship and Immigration Canada. Privacy of individuals is protected, and certain restrictions exist. Border Entry records also are available for immigrants arriving across the U.S./Canadian border between April 1908 and December 1935. However, not all immigrants were recorded. Some persons immigrated without being processed through ports when the ports were closed or where no port or governmental station existed. Others, for whom one or both parents were Canadian or who had previously resided in Canada, were considered “returning Canadians” and were not listed.

There also are registers of Chinese immigrants to Canada who arrived between 1885 and 1949.

It is important to know that the records are arranged by name of the port of arrival and the date of arrival, with the exception of the years 1923 to 1924 and some records from 1919 to 1922 when a separate governmental reporting Form 30A (individual manifest) was used. In addition, the Pier 21 Society of Halifax, Nova Scotia, has worked with LAC in inputting passenger list data from 1925 to 1935 and other border entry records data.

LAC provides an Ancestors Search facility at its website that allows you to enter the surname and given name and search one or all databases related to genealogical data. The direct link is http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/lac-bac/search/anc, and the search template is shown in Figure 10-14.

FIGURE 10-14 The top of the web page for the Ancestors Search facility at the Library and Archives Canada site

Home Children is a term used to designate the more than 100,000 children who were sent from Great Britain to Canada between the years of 1869 and the late 1930s. The intent was to provide a better, healthier, and more moral life for them. These were primarily poor or orphaned children, and rural Canadians welcomed them as cheap labor for their farms. (You may learn more about this phenomenon at the Young Immigrants to Canada website at http://www.dcs.uwaterloo.ca/~marj/genealogy/homeadd.html.) The archive contains a great deal of correspondence from sponsoring and administrative agencies for these children. Members of the British Isles Family History Society of Greater Ottawa are locating and indexing the names of these Home Children found in passenger lists in the custody of LAC. Details about the record holdings and a searchable database of these children are accessible on the web page at http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/genealogie/022-908.009-e.html.

Passenger lists and other records from before 1865 may exist in the provincial or territorial libraries, archives, and/or at maritime museums. The passenger arrival records in the custody of LAC that date from 1865 to 1935 have been microfilmed. They can be accessed in person by visiting LAC at 395 Wellington Street in Ottawa, through interlibrary loan among Canadian libraries, and/or through the LDS Family History Center nearest you. As mentioned before, digitized images are indexed and accessible at Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com) and Ancestry.ca (http://www.ancestry.ca).

An excellent strategy for researching immigrants into Canada would be to start with LAC and then seek additional resources in the appropriate province or territory. Please note that Canada does not maintain records of emigrations from Canada to other countries. If you are searching for an ancestor who immigrated to the United States, for example, you will need to refer to U.S. immigration records.

The history of Australia is a rich one, and it is the story of two peoples: the indigenous Aboriginals and the immigrants, primarily from England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland. The records of emigration from other countries and the immigration records into the country are mostly organized by geographical region. However, understanding some historical background can help you in understanding what is available and how to access the records.

Most people know that Australia was originally used by Britain as a penal colony. Most of the original colonial settlers were, in fact, convicts who were transported from the United Kingdom since 1788, along with the military personnel assigned to the colony.

Many criminal offenses in England during previous centuries could be punished by the imposition of extremely harsh and cruel sentences, ranging from public floggings to an appointment with the hangman, or to an executioner with an axe, if you were a “special” prisoner. During the 17th century, a more humane method of punishment was sought, and transportation to a distant wilderness environment was seen as an ideal solution. Thus, transportation began from the United Kingdom to the American colonies. Debtors’ colonies and criminal settlements existed for those condemned to penal servitude for a term of years or for life.

The outbreak of the American Revolutionary War halted transportation of criminals and undesirables to North America in 1775. While sentences of transportation were still passed by the courts, the convicts were remanded to prison. Before long, prison overcrowding created dire conditions. The government began to acquire older, perhaps no longer seaworthy ships, which were referred to as “the hulks.” These were fitted to house criminals, and thousands of convicts were sentenced to terms of imprisonment in these floating jails moored in coastal waters. The deplorable living conditions in both the prisons and on board the hulks reached a crisis stage, with rampant disease and escalating death tolls. The government sought a new location for a penal colony as a solution to the situation. In 1787, what has been called the “First Fleet” set sail from England for Botany Bay in Australia. A number of penal colony settlements were founded and maintained over the next 70 years. The military personnel assigned to administer the new penal colonies also brought their wives and families to settle there.

Emigration of free settlers from Britain and Ireland did not really begin until the early 1800s, and the number of emigrants was small in comparison to those migrating to the United States and Canada. In the 1830s and 1840s, a major exodus from Ireland saw many Irish farmers headed to both America and Australia. The gold rush in the 1850s provided another impetus for migration to Australia. The mining of opals became an important industry, with Australia now providing 97 percent of the world’s supply of opals. Therefore, opal mining also became an important draw for immigrant settlers.

Transportation as a punishment was effectively stopped in 1857, although it was not formally abolished until 1868. As you begin your research for Australian ancestors, you will want to familiarize yourself with the history of the judicial system in the United Kingdom at the time in question, and about the history of the penal colonies in the various areas of Australia. You also will want to try to locate the records of the criminal proceedings against your ancestor, the details of sentencing, and to what colony he or she was transported. This will help you trace the migration path.

Nowadays it is an “in thing” to claim descent from an early convict. In fact, Australian citizens often express the sentiment that the more convicts in the family tree, the merrier—and the more “ocker” (Australian) one becomes. So let’s look at convicts first. The earlier your ancestor arrived in Australia, the greater the probability that you are descended from a convict or from a member of the Crown government, an army or naval person, or a member of a ship’s crew.

You can often trace the path backward, although it may be more complicated to make that leap without understanding the ancestor’s circumstances and his or her offense. The database at the State Library of Queensland may provide details that can facilitate locating the criminal records in the court in the country of origin. Any additional information you can glean in advance may be crucial in distinguishing your ancestor from another person bearing the same name. Again, most of these records will be in the possession of the respective state or territory to which the person was transported.

It is important to recognize early on that the National Archives of Australia (NAA) on Queen Victoria Terrace in Canberra is the archives of the Commonwealth government. The records in that collection therefore date mostly from the Federation in 1901. That facility does not possess the records of convicts, of colonial migration, or of 18th and 19th century Australian history concerning such periods as the early exploration, the gold rushes, or colonial administration. They also do not have information about functions administered by the state and territory governments such as births, deaths, and marriages registers, or land titles. To obtain further information on these topics, it is necessary to contact the relevant state or territory registrar.

The National Archives of Ireland (http://www.nationalarchives.ie) has a searchable index database of transportation of Irish convicts to Australia between 1788 and 1868. Click the Genealogy link on the main page and then click Genealogy Records to locate the link for “Ireland-Australia transportation records (1791–1853).”

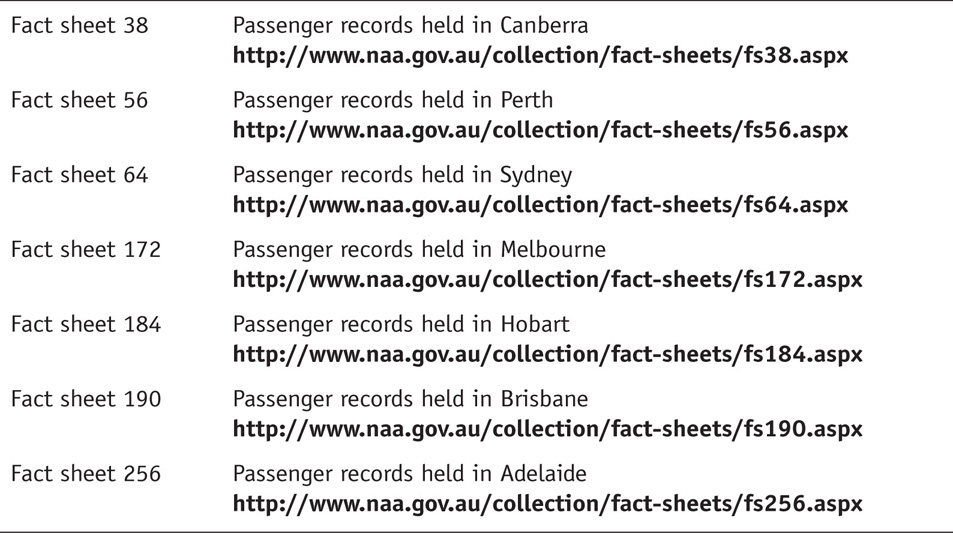

What the NAA does have, however, are immigration records relating to the 20th century dating primarily from 1924. The NAA does have some older records dating to the 1850s, but most of the records will be found in the respective state and territory archives. The NAA’s Fact sheets page can be accessed at http://www.naa.gov.au/collection/fact-sheets. You will also want to review specific fact sheets for records held in other offices of the archives as follows:

Fact sheet 2, located at http://www.naa.gov.au/collection/fact-sheets/fs02.aspx, is perhaps your most valuable online reference in the search for historical documents related to your genealogical research. It contains the addresses, contact information, and web address links for all of the major Australian archival institutions.

The State Library of Queensland has created the Convict transportation registers database at http://www.slq.qld.gov.au/resources/family-history/convicts. It contains details for over 123,000 of the estimated 160,000 convicts that were transported to Australia. The search results for individuals contain a substantial amount of information, which can include name, details of the crime and court, term of the sentence, date of transportation departure, name of the ship, and the place of arrival. The individual’s name and the court may be used to locate the extant court records in England or Ireland.

A database project to index names from the NAA’s many passenger arrival records from the 20th century (Record Series K269: Inward passenger manifests for ships and aircraft arriving at Fremantle, Perth Airport and outports, 1898–1978) is under way and currently includes arrivals from January 1921 to March 1951. The database is accessible through the NAA’s RecordSearch facility at http://recordsearch.naa.gov.au. You may search as a Guest, and there are several collections that you can access. One choice is the “Immigration and naturalisation records” group.

You will find extensive information about immigration to and emigration from Australia in the FamilySearch Wiki at https://familysearch.org/learn/wiki/en/Australia_Emigration_and_Immigration.

By now, you should have a much better idea of the types of information that are available for the various time periods and what records you may be likely to find. Remember that your early ancestors migrated across country from their places of birth and residence to ports from which ships sailed. They may then have sailed on one of these ships to emigrate across oceans. Also remember that, if an ancestor perhaps arrived in Canada and later relocated to the United States, there may have been several methods of travel and migration routes that were available at that time. Your ancestor may have crossed the border on foot or by some form of wheeled transportation, depending on the time period. These might include wagon, stagecoach, train, automobile, truck, or motor coach. Additionally, travel by boat, ferry, or ship might also have been an option. A combination of methods is also likely. You therefore will want to research the migration routes and transportation methods of the time for the geographical areas where your ancestor traveled.

The actual locating of the records is, of course, the real challenge. The following are some strategies you may consider employing in order to locate these records for your ancestors.

As with all effective family history and genealogical research, start with the most recent period and work your way backward. Any other approach, especially when researching back “across the pond,” can be unsuccessful. As you proceed backward, start with what other family members may know about immigrant ancestors. Look for home sources, including documentary materials that may have recorded immigration and/or naturalization details. These include family Bibles, letters, naturalization papers, voter registration documents, obituaries, and other documents. Another, older relative may even recall having heard Grandpa or Grandma discuss his or her trip to the new country, or something they recall having heard from another family member. While the intervening years may have dimmed or distorted the memory, there is likely to be a basis in fact with which to begin your research.

Census records provide milestones for establishing locations at regular time intervals. National censuses and state, territorial, and provincial censuses should be checked from the last census taken before the person’s death and tracked backward in time to locate the person at every enumeration, back to the parents’ home. Don’t overlook the information included on U.S. federal census records from 1880 forward, for example. Gather information on age, place of birth (if available), language spoken (if indicated), marital status, occupation, level of education, property ownership, and any other details. These can provide important biographical and historical context to help establish citizenship. The information you find about migration may point to immigration and country of origin.

Remember to be aware that a stated place of birth may have been in a different geopolitical jurisdiction at the time of birth than was listed on the census. Census enumerators’ instructions in the United States, for instance, stated that a foreign-born person was to tell where he or she was born and that the enumerator was to ask for the current name of the country in which that place was located. Boundaries and political jurisdictions did change over time. If you discover the country of birth for your ancestor in one census is different from that listed in a previous or subsequent census, it may indicate that a boundary change had taken place. Your understanding of the history and of geographical boundary changes is crucial to your successful research. These changes can help you home in on a specific geographical area. Furthermore, this knowledge enables you to determine the governmental entity in charge of generating official documents at the time. That entity and the places where its government offices were located then will help you determine where documentary evidence is to be found now.

In the absence of census records, and for the years between censuses, city directories and, later, telephone directories may help you establish locations. Addresses may help you identify property that your ancestor may have owned, and you may be able to follow up with government offices that maintain deeds and property tax records for additional information. Business listings that include proprietors’ names may help you determine where your ancestor worked.

Marriage and death certificates, as well as any ecclesiastical records, may provide crucial information concerning your ancestor’s origins. Church membership rolls and church minutes can direct you to other churches and locations from which membership may have been transferred. These may include congregations in the previous country of residence. This information may point you to a specific location or geographic area. You can then study migration patterns of the time when your ancestor lived there. These patterns may also point to commonly used ports of emigrant ships’ embarkations. You may also study the history of the area to help determine motivations for migrations.

One important record overlooked by many researchers is the voter registration record. These records typically are maintained at the county level across the United States and in governmental offices in other countries. Most times they are in a list format but sometimes the original voter registration application cards still exist. In order to vote in an election, an individual was supposed to be a citizen, and the voter registration records may include spaces to indicate the place of birth, when and where naturalized, how many years a resident lived in this voting precinct or ward, and so on.

Voter registration lists provide the court system in the area with the names of citizens who can serve as jurors. Jury lists may still be in the possession of the courts and may help verify the location of an ancestor at a specific time. Remember that women were not legally permitted to serve on juries until later times, and so you should consult the laws in effect at the time that your ancestor resided in an area before searching jury lists for a female ancestor.

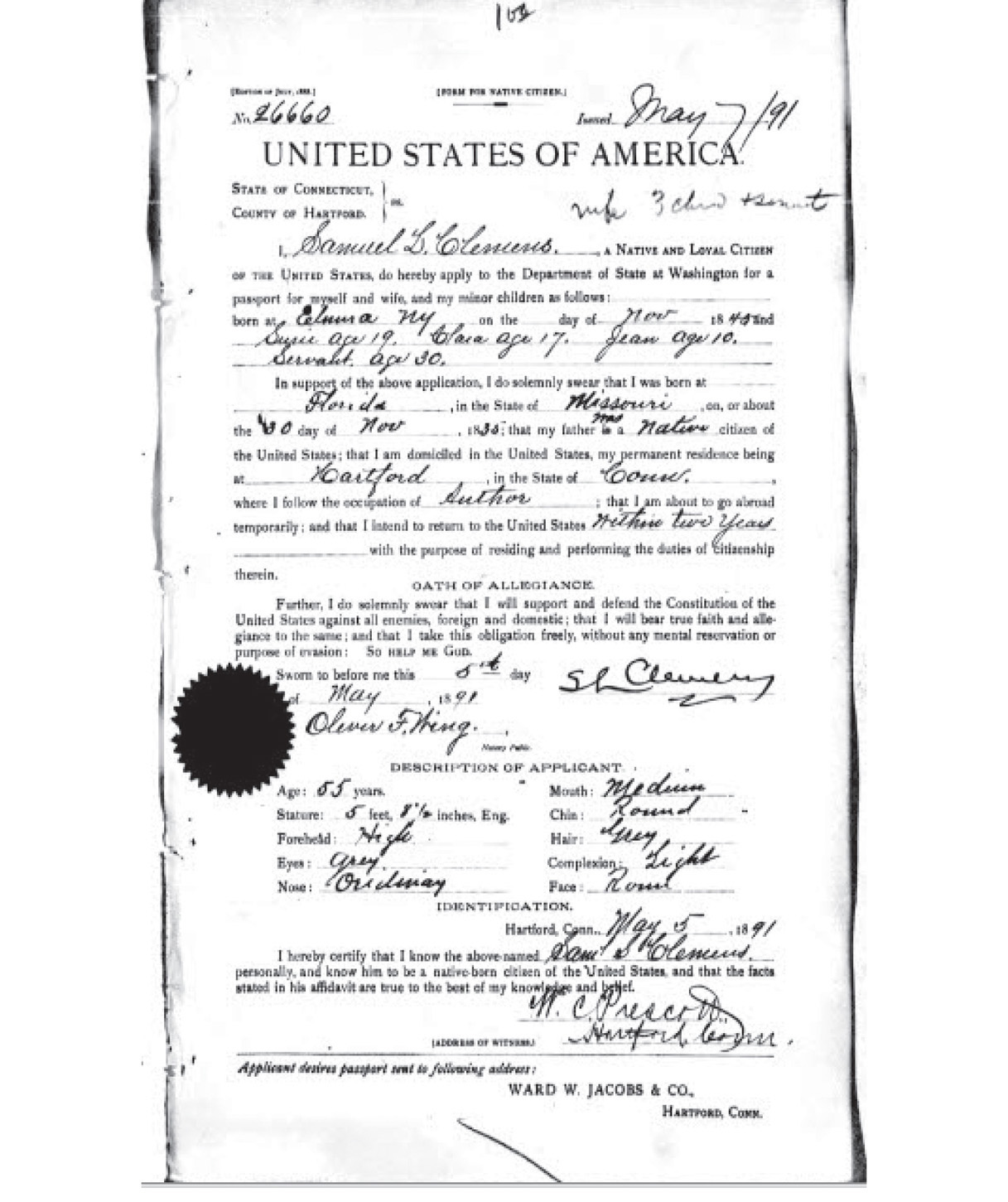

We discussed passport records in the United States earlier in the chapter. Certainly other countries issued passports for their citizens’ use in traveling abroad. Remember that it also is possible that your ancestor had to obtain a passport to return to and visit his or her homeland (and even to bring other relatives to America). Be sure to determine what passport application records might exist for your ancestor and how to access them. Figure 10-15 shows the passport application for Samuel L. Clemens, also known as author Mark Twain, from 5 May 1891.

FIGURE 10-15 Passport application for Samuel L. Clemens (also known as Mark Twain) from 5 May 1891

It is important to locate histories of the country and the locale from which your ancestor(s) may have come. Some of these published chronicles include the names of emigrants, their reasons for emigration, the migration paths they took, the time periods in which they relocated, and, in some cases, the names of the shipping lines (and ships) used.

One category of histories that should not be overlooked is the British genealogies that mention relatives who have gone to the New World. In the 16th and 17th centuries, heralds from the College of Arms would visit the various counties and record the pedigrees of families who aspired to armigerous status (meaning that they would have a coat of arms). Occasionally, there would be references to younger sons who had migrated or emigrated elsewhere.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, ambitious compilers of county histories would include pedigrees of the principal families of the county. Again, there might be the occasional reference to a relative who had gone to America, and perhaps even to a specified destination.

Finally, in the 19th and 20th centuries, the various volumes of pedigrees of landed gentry, peerage, and baronetcies, published by Burke’s Peerage and Gentry (http://www.burkespeerage.com), contain many references to American settlers.

By the same token, the companion to the histories discussed previously would be the historical publications concerning arriving immigrants at the other end of your ancestors’ journey. Local histories published in the area where your ancestors settled can also provide clues to your ancestors’ origin. While they may or may not include your ancestors’ names, they may provide details about the places of origins for specific groups of residents in the area. These may be important clues to neighborhoods, churches, local newspapers, and other resources for your research.

Google Books (http://books.google.com) is an excellent place to search for print and electronic books referencing your ancestors and their relatives. Google has digitized many thousands of older books that are out of copyright, and these are free. The Family History Books collection provided by FamilySearch contains almost 18,000 digitized and searchable family and local histories. The search template for this collection can be found at https://books.familysearch.org. Other digital collections can be found at Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com), in the HeritageQuest Online databases, at MyHeritage (http://www.myheritage.com), and at other sites.

By now, you should understand more clearly that there are more paths to follow than just one in the search for your ancestors’ records. When the place of birth, previous residence, or other indication of native origin is conveniently and clearly marked, you can be thankful for more modern records. However, when you don’t have such crystal-clear directional markers, what are you to do?

Determining your ancestral origin can be a tricky thing but it is not always impossible to ascertain. Numerous strategies are employed, so let’s look at a few. This list can never be complete because each nationality has its own nuances, but you must invest some thought and ingenuity to reach out to your ancestors’ stories and traits.

If your ancestors came to America between 1850 and the present, photographs of them may very well exist, especially in family photographic collections. An examination of clothing, hairstyles, shoes, jewelry, and other objects in the picture may be helpful in determining your ancestral origin. On older photographs mounted on cabinet card stock, there may even be the name of a photographer and a location. Researching the photographer or studio can be an interesting study as well, and it is not unusual to find a particular photographer having taken photos in a specific area or neighborhood in which a national or ethnic group lived.

If you encounter letters written in another language among the family possessions, or Bibles and books in another language, start asking questions. These may be indicative of the nativity of members of your family or your ancestors. It may also be possible to have these items translated into your language so that you can understand them and potentially gain more clues.

Are there specific customs in your family you don’t understand? One researcher wondered why the family always ate marinated herring at Christmastime, only to discover later that it was a residual custom from her maternal grandmother, whose family always ate it at their home outside Uppsala, Sweden. And are there songs in another language that are sung, such as hymns or lullabies? They might provide other important clues.

Ethnic or national cooking is always an interesting tip-off, though not always. Your grandmother’s goulash may be indicative that she had ancestors in Hungary.

One African-American friend heard a lecture at the National Genealogical Society Conference in Denver, Colorado, in 1998, by Tommie Morton-Young, Ph.D. In that lecture, “African American Genealogy: New Insights Using Traditional and Less Traditional Methods,” Dr. Morton-Young discussed that there are physical characteristics of some African peoples that may be used to trace ancestry of slave ancestors back to a particular geographical area and perhaps even to a specific tribal group. The physical traits in this case were the size and shape of the ear, the shape of the nose, and the physical size of the ulna. It is a very interesting approach, and it might really matter.

The U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services website, as mentioned before, provides some of the most important historical and reference materials for your immigration and naturalization research. USCIS is located at http://www.uscis.gov. However, access the Genealogy Notebook at http://www.uscis.gov/history-and-genealogy/genealogy/genealogy-notebook, which contains a number of excellent articles. The “Our History” section and the “History and Genealogy News” section provide important educational materials for you. Look for the link to the Historical Library, where you will find a link labeled Legal History Resources. The immigration and naturalization laws for different time periods from 1893 forward can be studied here.

The naturalization process has varied in every location we will discuss here, and has evolved over time to produce more consistent practices with more standardized and detailed records. The focus of this section is United States naturalization, but your study of naturalization practices in England and Wales, Scotland, Ireland, Canada, Australia, and other locations can provide you with the knowledge and legal background to help understand those places’ laws and requirements.

As our forebears began their new lives in new communities, they strove to “fit in” and to normalize in the new environment. Most realized they would never return to their previous lives, and they eagerly embraced their new circumstances. This meant renouncing their political ties to their motherland and applying to become citizens of their new country.

Naturalization in the United States, like the ships’ passenger lists and manifests, has changed through the centuries of the country’s existence. Different methods of handling the process, different laws and requirements, different forms, and different places where the process was handled all add up to what can be a challenging research effort. There are many intricacies and exceptions and, as a result, we have to do some self-education to learn the details of the history of naturalization in the United States. To that end, Loretto D. Szucs’s book They Became Americans: Finding Naturalization Records and Ethnic Origins (Ancestry.com, 1998) wins my applause for the best volume on the process, and is illustrated with scores of document examples. However, in short, there are four principal documents associated with naturalization in the United States:

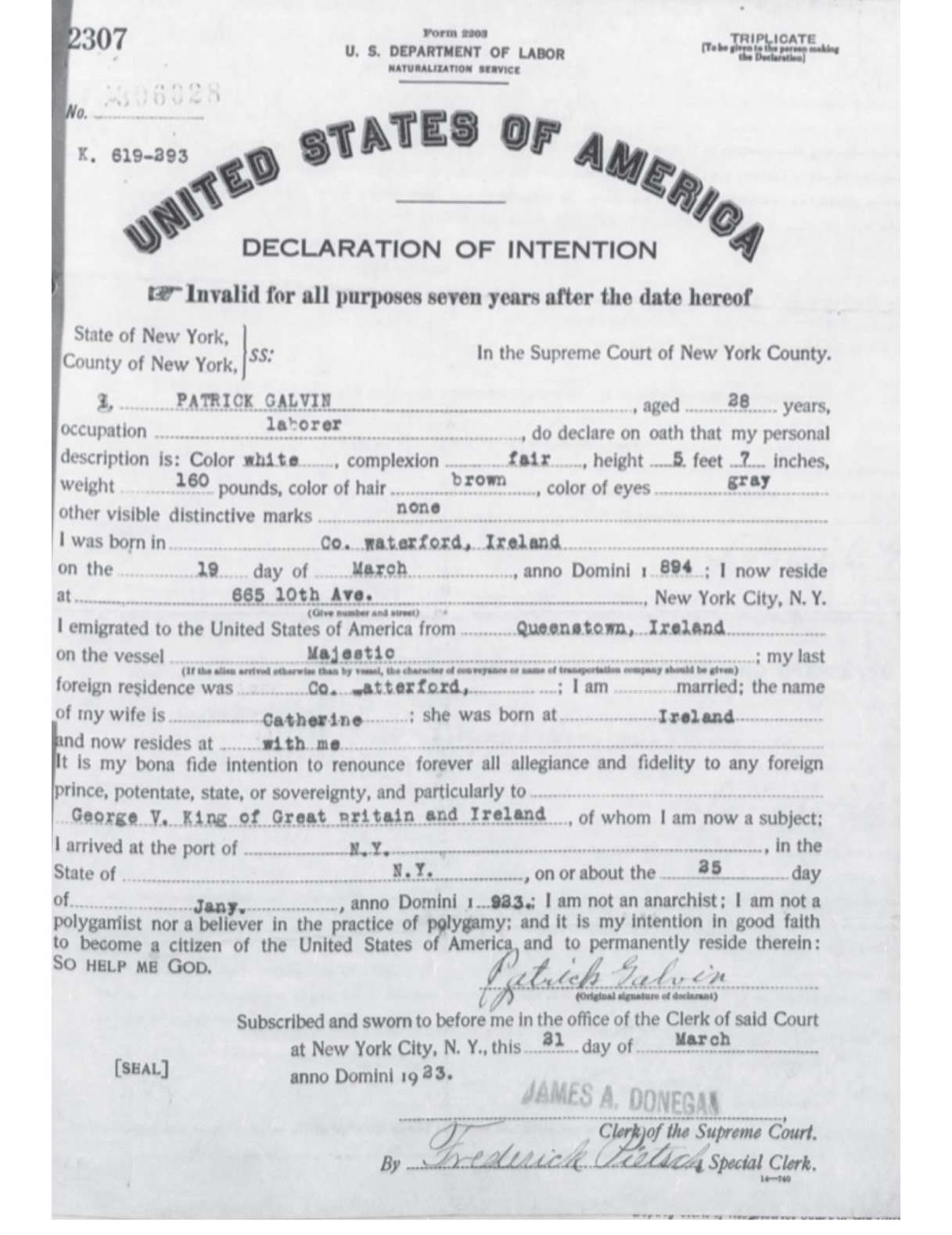

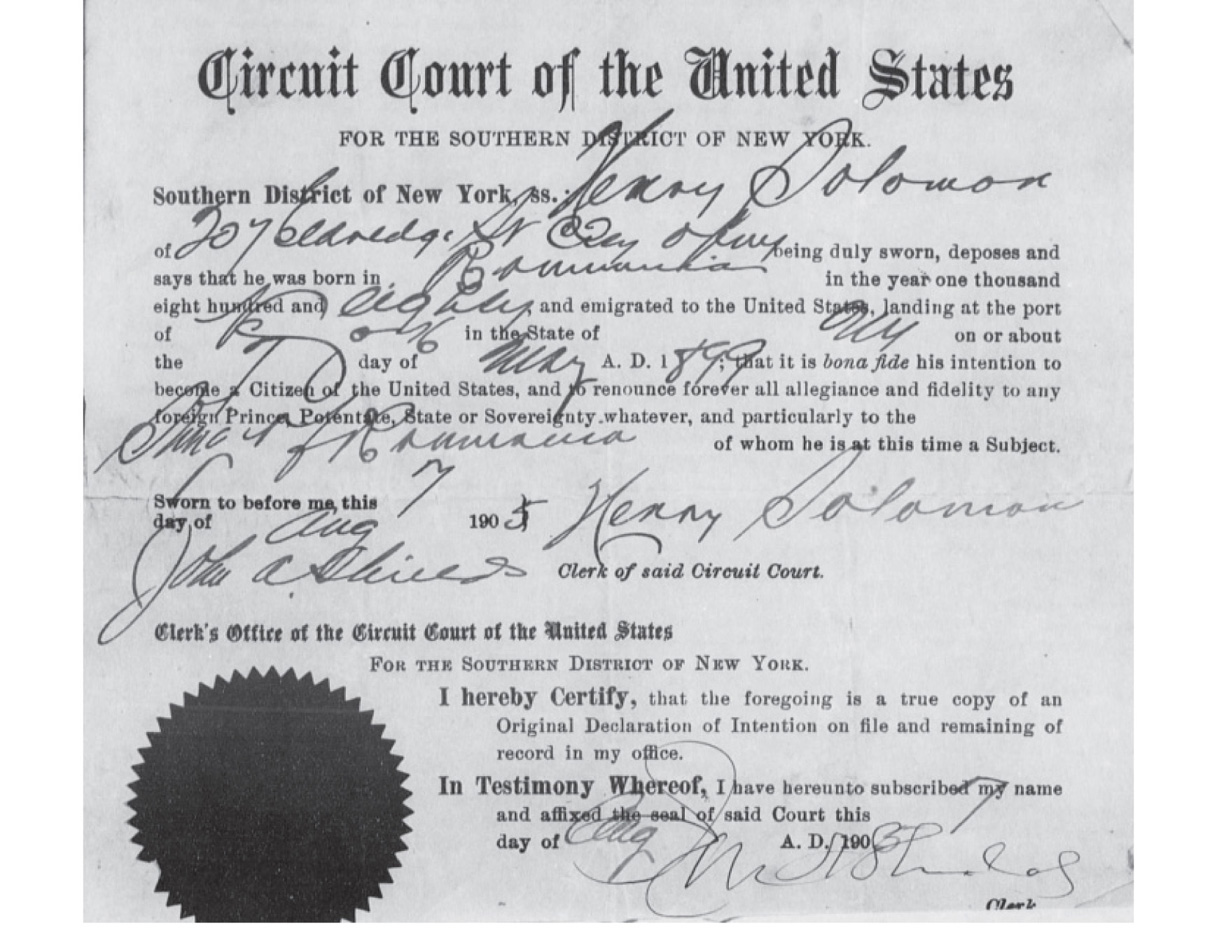

• Declaration of Intention This document (also sometimes referred to as first papers) is signed by the immigrant, renouncing citizenship in his/her previous country and any allegiance to the country and/or its ruler or sovereign. It expresses the individual’s intent to petition the United States to become a citizen after all requirements are met. The format varied over time, as you can see from the examples in Figures 10-16 and 10-17.

• Petition for Naturalization This document (also referred to as final papers) is the application that the person completes and submits to request the granting of citizenship, typically after satisfying residency requirements and after filing first papers. Figure 10-18 shows an example of this document, and Figure 10-19 shows the court document granting permission to take the oath of allegiance.

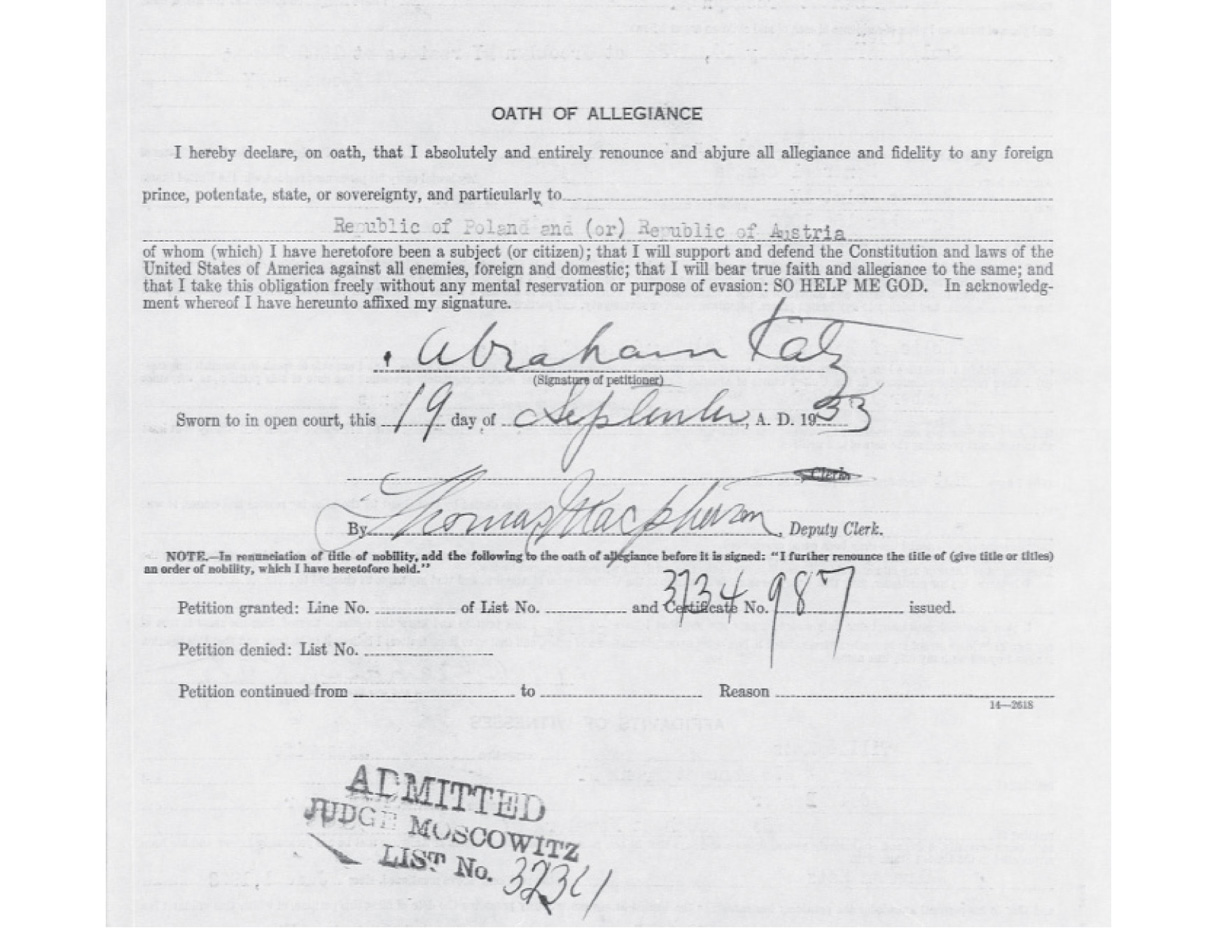

• Oath of Allegiance This is the document that is signed by the petitioner for citizenship at the time citizenship is granted (or restored), swearing his/her allegiance and support to the United States. This may or may not be included in the naturalization file for your ancestor.

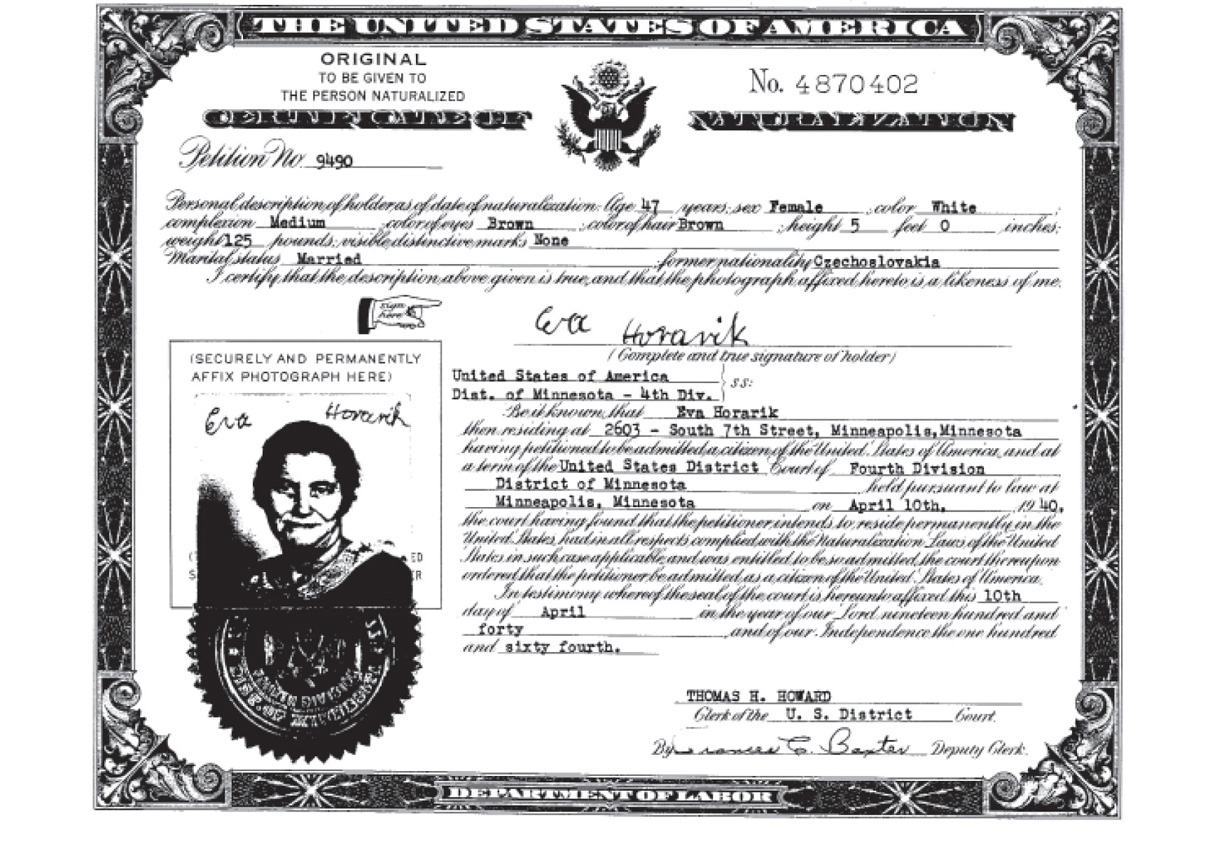

• Certificate of Naturalization This is the formal document issued to the petitioner to certify that he/she has been naturalized as a citizen of the United States. Figure 10-20 shows a certificate from 1940.

FIGURE 10-16 Declaration of Intention (from 1923)

FIGURE 10-17 Declaration of Intention filed at the Circuit Court of the United States for the Southern District of New York (from 1905)

FIGURE 10-18 Petition for Naturalization to the Circuit Court of the United States for the Southern District of New York (from 1927)

FIGURE 10-19 Oath of Allegiance (from 1933)

FIGURE 10-20 Certificate of Naturalization (1940)