Recognize when you have hit a “brick wall”

Recognize when you have hit a “brick wall”

Look for alternate record types

Look for alternate record types

Take a fresh look at your evidence

Take a fresh look at your evidence

Reevaluate the quality of your sources

Reevaluate the quality of your sources

Widen the scope of your search to include new and different sources

Widen the scope of your search to include new and different sources

Use photographs

Use photographs

Develop an ancestor profile/timeline

Develop an ancestor profile/timeline

Switch to another family member to bypass your roadblock

Switch to another family member to bypass your roadblock

Seek help from libraries, archives, and societies

Seek help from libraries, archives, and societies

Engage the help of a professional researcher

Engage the help of a professional researcher

Consider some common brick walls

Consider some common brick walls

Inevitably you will confront the genealogist’s worst nightmare: the dreaded “brick wall.” Despite all your best research efforts, your careful assessment of the evidence, documentation, and facts, the quality of your source materials, and your best hypotheses, you’ll find you just can’t progress any further. It happens to all of us, but the situation isn’t always hopeless.

We have explored the most common record types, and you have learned about methodologies for using them to discover and document more about your ancestral families. There are literally hundreds of other types of records and artifacts that may provide valuable clues or data to expand your research. This chapter will provide an introduction to some of these resources.

Drew Smith and I wrote a book, Advanced Genealogy Research Techniques (McGraw-Hill, 2013), in which we address many ways of getting around research roadblocks. In addition to what you have learned here, I recommend that book as another resource to extend your genealogical research.

Sometimes a person you think is going to be the simplest to locate becomes a dead end. Every avenue you explore seems to come to an abrupt halt. One of the most frustrating things is not being able to locate even the most basic vital or civil records that should have been where you expected to find them. Worse yet is the discovery that the person who you thought was your ancestor and in whom you’ve invested a great deal of research effort actually is not related to you at all. You’ve been researching someone else’s ancestor!

Unfortunately, it is easy to become so consumed with the “ordinary” search that you may not even realize you’ve hit the proverbial “brick wall”. The work you’ve done to hone your critical thinking skills can now provide the biggest payoffs.

There are several keys to solving your problem. The first thing to do is to recognize the fact that you really do have a brick wall, and that you haven’t just made an oversight. Identify and literally describe the scope and symptoms of the problem. Write a description of your problem, including what you know to be fact and the sources of every fact in evidence. Also list pieces of evidence that are very solid or don’t quite fit, and write the reason(s) why you believe as you do. Include in your description what you want to find out, what you already have searched, and the results you have or have not achieved. Finally, describe the brick wall and why you think it has stopped your research. Often, just putting the facts and the actions you’ve already taken into words on paper can help focus your attention on the real issues. Here are examples of just a few of the more common categories of research brick walls you can expect to encounter:

• Your ancestor’s name is a common one, or there are numerous people of the same name in the same geographical area.

• You can locate no records for your ancestor—anywhere!

• You cannot identify your ancestor’s parents or cannot link him or her with people who you believe are or might be the parents.

• Records have been lost, stolen, destroyed, or transferred elsewhere, and you can’t absolutely determine what happened to them.

• Records that you want to access are private, restricted, or entirely closed to the public.

• No resources can be found on Internet web pages, in Internet-based free or subscription genealogical databases, and/or in those databases accessible through libraries and archives.

• Books or manuscripts are not readily available or are located far away.

• You are unable to confirm that a person you think is your ancestor really is your ancestor.

Using your written description of the problem and the resources you have already researched, now develop a list of alternative research paths, records, and other sources that might help resolve the problem. You may need to conduct some additional research to put your ancestor into geographical, historical, and/or social context and to determine what records might or might not exist to help you locate more information. You may not know about all the various alternative resources that might be available. Your continued reading, research, and collaboration with other genealogists can help you learn about these resources and how to maximize your use of them. We will look at some examples of problems and possible solutions in this chapter’s final section, “Consider Some Common Brick Walls.”

Alternate record types encompass many different types of materials, as you have seen. You are sure to encounter many materials in the course of your family history odyssey that can reveal facts or clues. We discussed in Chapter 7 the many types of death-related records (see Table 7-1), and I suspect you were astonished at the extensive number of source materials listed there.

American researchers lament the loss of the 1890 U.S. federal census population schedules. They understand that they have to look for other documentary evidence to help place their ancestors in a specific geographical location in the years between the 1880 and 1900 censuses. Here are just a few of the alternate records that can be used for this purpose, in alphabetical order:

• Cemetery records

• Church membership lists, bulletins, and other publications

• City directories

• College and university records and yearbooks

• Family Bible

• Family photographs

• Grantor and grantee indexes to property deeds

• Jury lists

• Letters, postcards, diaries, and journals

• Licenses (business, dog, professional, and other)

• Local histories

• Lodge and fraternal organization records

• Newspapers (local and trade union)

• Property tax rolls and tax lists

• School records (censuses) and yearbooks

• Telephone directories

• Voter applications and registration lists

• Wills and probate records (of the person and/or other family members)

English and Welsh researchers are fortunate to have civil registration records dating back to 1 July 1837 that record births, marriages, and deaths. Prior to that and back to the reign of King Henry VIII, parish records for Church of England congregations have been kept for christenings, marriages, and burials. Americans are not so fortunate in that there was no national law requiring registration of births, marriages, and deaths. That legislation was up to the various states’ legislatures. Marriage records were maintained early on to document legitimacy of children and their legal right to inherit. However, governments in many states did not record births and deaths until well into the 20th century. American researchers therefore must rely on alternative records to help establish/document the date of birth for an ancestor. Here are some examples, in alphabetical order, of alternate records that might be used to help determine an individual’s date of birth:

• Baby book

• Birth announcement (printed)

• Census population schedule (age or month/year)

• Church christening or baptism records

• Church membership record or church minutes

• Death certificate

• Family Bible

• Funeral home records

• Letters between family members

• Licenses (business and driver)

• Life insurance applications and redemption documents

• Military records (draft registration, enlistment, service records, pension records)

• Newspaper account of baby shower

• Newspaper birth announcement

• Obituary

• Photographs (labeled/dated)

• School records (enrollment and school censuses)

• Social Security Death Index (SSDI)

• Synagogue records; bar mitzvah/bat mitzvah records

• Tombstone

• Will and probate records and probate court minutes

Be sure not to ignore artifacts found among home sources and heirlooms. Family Bibles can provide clues to other records, even if the Bible itself is a secondary source. Other materials however can be of significant value. They may or may not be dated, but they can provide clues about your ancestors, including their level of education, their talents and skills, and other information, all of which can help you build context for their lives.

One strategy that I consistently use is the reexamination of documentation and other evidence that I have previously collected. It amazes me how much information can be gleaned from taking a fresh look at something that I thought I knew so well. Remember that over time you will gather new evidence of many types; learn more about history, geography, and other influences; and become acquainted with new people in your family history.

Scholarly work is one of the goals of genealogical research and we are therefore always searching for the best evidence we can find. It is certainly gratifying to locate an original marriage certificate, created at the time of the marriage and bearing the actual signatures of the bride and groom. Few things are as exciting as holding and touching a document that was handled and signed by our ancestors and that was as important to them as a marriage certificate. The next best thing, of course, is seeing a facsimile of such a document on a photocopy, on microfilm, or as a digitized image. You already know that there are more and more digitized images being made available on the Internet every month.

Not all of our source materials, however, can be such excellent forms of evidence. As you’ve learned, genealogists work with sources of both primary and secondary information; with data transcribed, extracted, and abstracted from original documents; and with a vast array of published materials in all types of formats. In our quest to locate facts about our family, we often must use sources that may be one or more times removed from original source material, and often this information is less than 100 percent accurate. There may be something lost in the transfer, diluted as it were, and it is for that reason that we must maintain a keen awareness of primary vs. secondary information and be prepared to carefully analyze the quality of our sources.

An original marriage license would, indeed, be a great find. For most of us, however, the closest we will get is the entry in a county marriage book. Remember that the clerk transcribed that entry from the original marriage return document, and that errors might have been introduced.

Another problem we have occurs when all of the pieces of evidence we have acquired are not original or primary in nature. I often tell genealogists, “Two secondary sources do not a primary source make.” Perhaps it sounds a little corny, but it is emphatically true. I recommend maintaining a healthy skepticism of almost any information until its authority can be proved, and then evaluate the weight that it may provide to the big picture.

One major factor contributing to many of our research brick walls can be a problem with the quality of the information we may have obtained from source materials. It is important to take a giant step back from a problem and reexamine all of our evidence. I don’t mean “just” the sources of secondary information, but everything. As I said earlier, a great way to do this is to arrange every piece of evidence you have in the chronological sequence as it may have occurred in the ancestor’s life. Reread everything in the chronological order of the events as they occurred. You are sure to find gaps in what you know. In the meantime, reexamine where your information was derived. What you may think is a solid fact may be well documented by a less than excellent source. Let me give you an example.

A friend in Georgia hit a brick wall in her search to prove the identities of the parents of her grandmother and locate other documentation about them. She had a death certificate for her grandmother that documented the date of death as 4 October 1935 and indicated the place of burial was to be in Munford, Alabama. The certificate stated that her grandmother had been born on 22 June 1859 in Atlanta, Georgia, and that she was 78 at the time of her death. The only information my friend had about the names of her great-grandparents came from the death certificate, and she inferred from the place of birth listed on her grandmother’s death certificate that her great-grandparents had lived in Atlanta.

You will remember that a death certificate can be one of those “combination” sources: a source of primary information about the death and a source of secondary information about almost everything else. My friend knew that well, but still had entered the information she found on the death certificate into her genealogical database and documented the source. However, in her concentration on locating documentation on her great-grandparents, she failed to recognize that the only information she had about their names and the place they lived was the information from this death certificate. It turned out that the informant who provided the information for the death certificate was a nephew, and that he really did not know the facts about the date and place of birth, the names of the parents, and their place of residence. One glaring error was in the age shown on the certificate. Wait a minute! When I subtract 1859 from 1935, I come up with 76, not 78! Something was amiss here. And why was she to be buried in Alabama?

My friend backed up and began her research again, this time with a fresh perspective. She knew that she had made an error in judgment in assuming that the names, dates, and locations on the death certificate were “probably correct.” She now knew that she needed to search for additional source materials. Her next step was to begin again with what she really knew to be factual based on primary information. She developed a list of document sources that might be available and that might help her solve her research problem. She did some research to determine where those documents might be located, and then began making contact with those locations to see what she could obtain by mail or email. She ultimately arranged to make two short trips to conduct on-site research.

After about a year, she told me that she had solved some problems and had finally gotten around her brick wall. There were four important pieces of information she had obtained from other materials that helped her:

• She located a copy of her grandmother’s obituary, which indicated that she grew up in Greensboro, Georgia. It listed her age as 78, and not 76, and confirmed that burial was to occur in Munford, Alabama.

• She traveled to Alabama and located the cemetery where her grandmother was buried. Her grandmother’s grave was next to that of her grandfather in his family’s cemetery lot. That made sense. She also noted on her grandmother’s gravestone the birth date of 22 June 1857, yet another confirmation of the age of 78 and not 76 years. While information carved on tombstones is definitely secondary in nature, in this case the information contradicted what the nephew had provided for the death certificate.

• She reexamined her grandparents’ marriage certificate and noted the marriage date of 24 November 1881 and the place of issue as Greene County, Georgia. As it was often customary for a bride to be married at home or in her church, my friend believed it made sense to pursue research in Greene County and not in Atlanta.

• She traveled to Greensboro in Greene County to search for records of her grandmother’s family. She located microfilmed copies of the local newspaper in the public library and began searching for marriage announcements. She found the announcement in a newspaper dated Thursday, 8 September 1881, and the notice included her grandmother’s name, the name of her fiancé, and the names of both sets of parents and their places of residence.

Armed with the new information, my friend continued her research in Greene County and located a vast amount of information about her grandmother’s family. She found church records, land and property records, tax rolls, and a probate packet for her great-grandfather in which his children’s names were listed. Now knowing the correct state and county, she continued by working with the 1880 federal census records for Greene County to verify the family’s residence there, the names of the children, and their ages. Furthermore, my friend learned that her great-grandfather had been the county sheriff for many years, including at the time that her grandmother had been born in 1857. She has been trying to determine whether her grandmother really was born in Atlanta or in Greensboro.

My friend’s story is not uncommon. Even though her brick wall was a comparatively simple problem, it illustrates how a small error in judgment or an assumption can result in a major blockage in a person’s research. This case required stepping back and reexamining the source material, followed with the development of an additional research plan, and some concentrated research to get around her brick wall. Since that time, she has extended her research to include other of her grandmother’s siblings and has been able to identify and document her great-grandmother’s parents and grandparents. She is still on the right research track, and she has extended her factual evidence by three generations.

Obituaries can offer tremendous clues for genealogical research. And even though they are distinctly sources of secondary information and prone to errors, they can provide pointers to a wide array of resources. Unfortunately, though, many researchers fail to get the most from an obituary.

A method of mining information from an obituary that really works involves dissecting the obituary. The process involves identifying every possible component that states or infers a fact, determining what evidentiary sources might exist to document or substantiate the fact, and then identifying where each source might be located.

Figure 14-1 shows a transcription of the obituary for a Tampa, Florida, resident who died on 30 December 1998. You can use a photocopy of an original obituary for your dissection. I have underlined each component that might point to sources of evidence about Mr. Nathaniel Cannon, Sr.’s life.

FIGURE 14-1 Transcription of the obituary of Nathaniel Cannon, Sr., from the St. Petersburg Times on 2 January 1999

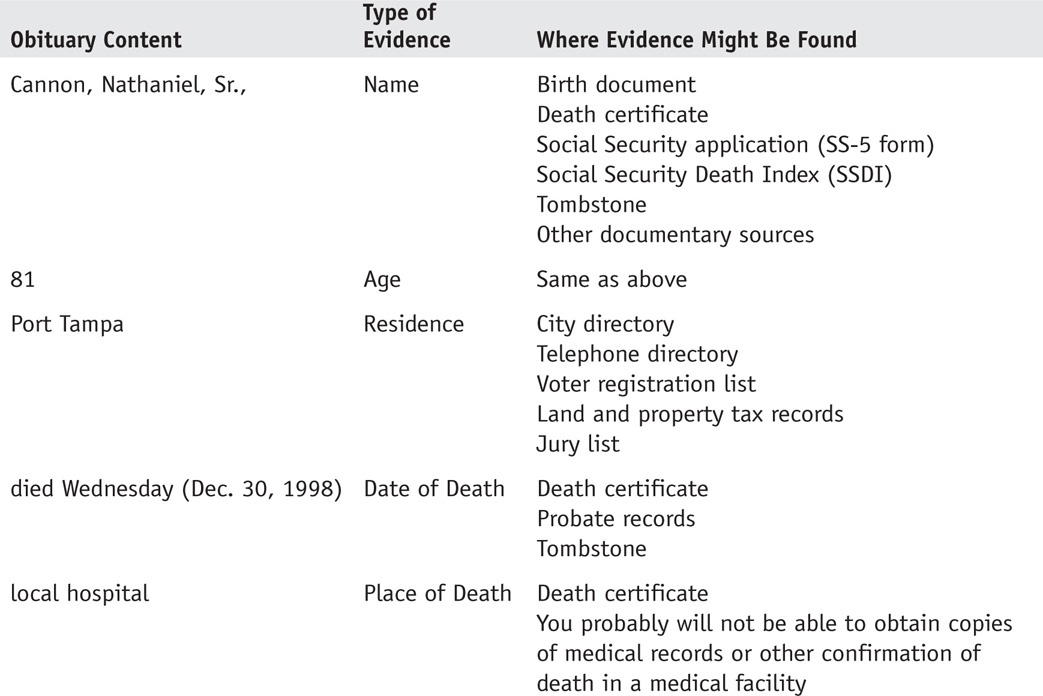

The following table shows the component pieces of information that may point to other information, what that evidence may be, and where it might be located. Some of these records may be sources of distinctly secondary information, such as the tombstone, directories, and so forth. They should not, however, be overlooked as they can provide another source of corroboration of the fact in consideration.

You can see that this obituary is packed with informational details that provide clues to other evidence. Some of this evidence will take the form of documents, while other sources will include making contact with family members, friends, fellow church members, and other people. Don’t ever overlook a cemetery’s office; its files may contain letters, a burial permit, records of the installation of a marker, a copy of a death certificate, and possibly a transit permit.

Once you have dissected the obituary for types of alternative records, take the time to consider the places where each of those records might be found. Next, determine how you might access the records from the places where they are located. Remember that exact copies in various formats such as microfilm and digitized may be available in multiple places. You can then prepare your research plans to locate the records and access them for your personal examination. This may involve making a visit to a specific repository, writing letters or making phone calls, working with a database of digitized images, or some other form of accessing copies for your personal examination and evaluation.

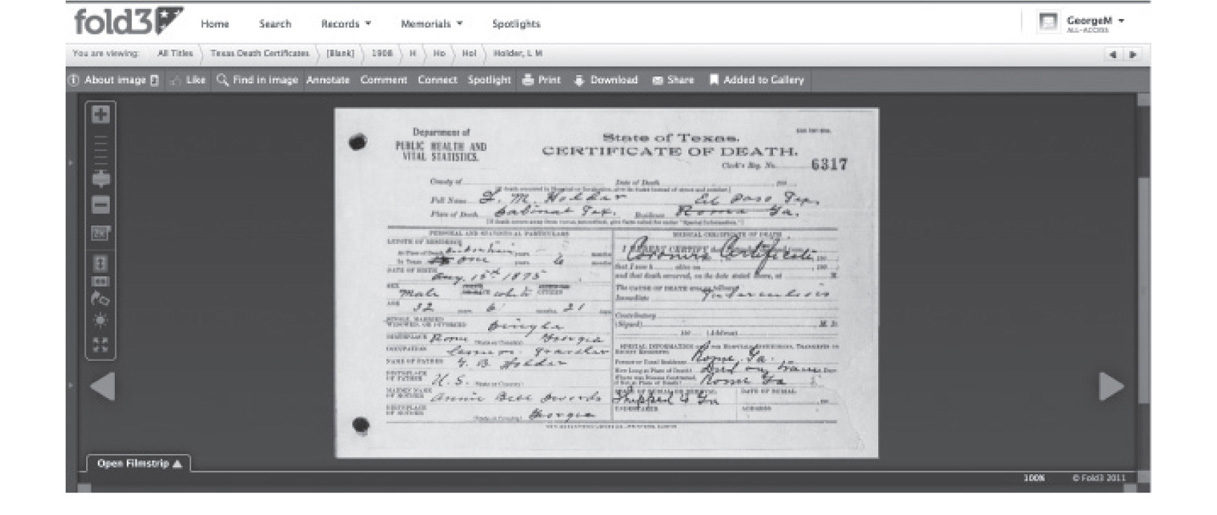

One of the joys of genealogy is learning about different resources that can be used to document your family history. Discovery of these materials is exciting and invariably leads to a desire to learn more about them. I remember my excitement at learning about transit permits, those documents that are used to facilitate the transport of bodies across state or national borders to a hometown or some other place of interment. A transit permit can contain a great deal of information about the individual and, prior to the use of official death certificates, can provide details about the cause of death. In the course of my research, I have encountered transit permits in cemeteries’ files for soldiers in the U.S. Civil War who died in battle or from disease. I even found a death certificate for my great-uncle, Luther Moffett Holder, who died of tuberculosis en route by train from New Mexico to Georgia. A digital image found on Fold3 gave me the documentary proof I needed to confirm his death in 1908 (see Figure 14-2).

FIGURE 14-2 Death certificate of the author’s great-uncle, Luther Moffett Holder

I’ve also seen transit permits for a woman killed by a train, people killed by gunshot wounds, several suicides, and for people who died from any number of different diseases. Transit permits that allowed the transport of Civil War soldiers’ bodies from one state to another may still be inside cemeteries’ administrators’ files or inscribed in interment books. These may be the only records of the causes of death of these soldiers. This certainly is not unusual in the offices of administrators and sextons in Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia, and other places worldwide.

There are literally hundreds of documents you may never have imagined existed that could help you document your ancestors and family members. Beyond the record types I’ve covered in this book, you will want to consider other sources. How do you find out about them? Well, there are all sorts of books available that can introduce you to descriptions and samples of these records. Let me share a few of my favorites.

Hidden Sources: Family History in Unlikely Places, by Laura Szucs Pfeiffer, is a compilation of more than a hundred different record types that may be of help to your personal research. Each record type is described in detail, along with information about places where it can be located and how it can be used. You will find an illustration included for each record and a bibliography for additional reading and reference. Some of the more interesting records are almshouse records, coroner’s inquests, bankruptcy records, Freedmen’s Bureau records, name change records, orphan asylum records, passport records, school censuses, street indexes, post office guides and directories, patent records, and voter registration records.

Another excellent compilation is Printed Sources: A Guide to Published Genealogical Records, edited by Kory L. Meyerink. This impressive book contains authoritative chapters concerning different record categories, written by a number of eminent genealogical experts. For example, if you are looking for a more thorough understanding of U.S. military records, David T. Thackery’s chapter, “Military Sources,” is a comprehensive study of what types of records are available and a selective description of published sources for major military conflicts. Records at the federal, colonial, and state level are addressed in detail; histories, rosters, and important reference works are described; and a vast, definitive biography is included.

A study of English parish records requires some understanding of the structure of the parish system and of the social responsibilities of the parish officer. The Compleat Parish Officer is a reprint by the Wiltshire Family History Society of a 1734 handbook for those persons “who had to apply and interpret the increasingly complex laws enacted to deal with the various social problems as they arose, its starting point being the Great Poor Law Act of 1601 and its various amendments.” This compact little book details the authorities and responsibilities of parish constables, churchwardens, overseers of the poor, surveyors of the highways and scavengers, and other officials in the parish operational hierarchy. It is an invaluable primer for genealogists and family historians in understanding the English parish environment and the records that are found documenting your ancestors.

A companion to The Compleat Parish Officer is Anne Cole’s An Introduction to Poor Law Documents Before 1834. This volume describes the parish documents, explaining the reasons for each one’s creation, the contents, and what can be gleaned from them. The settlement certificate, for example, was an exceptionally important document for those to whom it was issued. It provided legal proof of residence in the parish and thus, in time of need, entitled the person to financial assistance. However, more importantly, the settlement certificate was used to provide permission to persons to relocate their place of residence from one parish to another. These two books, used together, provide excellent insight for the researcher of English parish records.

The few examples I’ve provided here merely begin to scratch the surface of the wide range of record types that can be found and used for your genealogical documentation. I urge you to use the resources of library and archive catalogs, particularly the subject and title search facilities of their online catalogs, to locate books of interest for these topics. In addition, you will find that using the bibliographies included in many genealogical and historical publications will lead you to more reference materials. Further, be sure to check out digitized books available at Google Books (http://books.google.com) and other online venues that have been discussed earlier in this book.

If you’re like most people, you have a collection of photographs stored somewhere in your home. Many of these may be identified and labeled, but you probably have a substantial group of unlabeled photographs, and I refer to these in my home as “the unknowns.” You will find that photographs can, indeed, be helpful in identifying persons and placing them in a specific place at a particular point in time.

Photographs have been around since the production of the first photographic image in the summer of 1826, which is universally credited to Frenchman Joseph Nicéphore Niépce. Over time, other processes and methods of mounting or displaying photographs were developed and introduced. You will find that the type of photograph and its physical attributes, the mountings used, the clothing and hairstyle worn by the subjects, and the background or surroundings can be used to date your photographs with surprising accuracy. It is important to understand a little history of photography first.

Louis Daguerre’s technique of capturing an image on a silver-clad copper plate was officially announced in 1839. These first commercially successful photographs were known as daguerreotypes and were, at the time, quite expensive. A daguerreotype was usually attached to a sheet of glass using a decorative frame made with a sheet of gold-colored heavy foil. The decoration was usually embossed into the foil material before enclosing the daguerreotype and its glass. This unit was then press-fitted into a wooden case specifically designed to hold a daguerreotype and sometimes padded with satin, silk, or velvet. The case also may have been a two-piece, hinged affair with a clasp that closed and protected the daguerreotype.

The calotype was the first paper photograph, and it was made using a two-step process. The first step involved treating smooth, high-quality writing paper with a chemical wash of silver nitrate. This wash process was performed in a dim, candlelit room and the paper was then exposed to a little heat until it was almost dry. While still somewhat moist, the paper was soaked in a solution of potassium iodide for several minutes, then rinsed and gently dried. The chemical processes in effect iodized the surface of the paper to prepare it for its ultimate exposure to light. The slow drying process preserved the smooth texture of the paper, preventing wrinkling and puckering of its surface. The iodized paper could be stored for some time in a dark, dry place at a moderate temperature. The second step occurred almost immediately before the iodized paper was to be used for a photograph. The photographer mixed a solution of equal parts of silver nitrate and gallic acid that, because of its inherent instability, had to be used right away. Once again, in dim candlelight, the iodized paper that had been prepared in the first step was dipped in this solution, rinsed with water, and blotted dry. It was then loaded in complete darkness into the camera and the calotype photographic image was captured. While the paper treated to the second solution could be dried and stored for use a short time later, the most reliable images were captured using paper still moist with the solution. Calotypes were made for perhaps a decade, from approximately 1845 until 1855. The main problem with them was that because the silver nitrate–gallic acid solution was not chemically stable, many of the images faded over a relatively short time. The surviving examples of many of these early calotypes appear as shadows or “ghosts” on the paper.

The ambrotype was introduced in 1854 and became very popular throughout the United States during the Civil War period. An ambrotype is a thin negative image bonded to a sheet of clear glass. When the negative image is mounted and displayed against a black background, the image appears as a positive. Ambrotypes were mounted in display cases much like those used for daguerreotypes.

Photography gained huge popularity in Great Britain when it was showcased at the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London. Both Queen Victoria and her husband, Prince Albert, were fascinated with photography and there are numerous photographs of the couple and other members of the Royal Family dating back to the 1840s. The public was introduced to several displays of photographs in various locations at the Exhibition, and a subsequent increase in photographers’ business in England has been attributed to that event.

The tintype was introduced in the early- to mid-1850s and was in use until the early 1930s. It became hugely popular in both the United States and Great Britain because it was cheap to produce and therefore accessible by almost everyone. Advertisements of the time touted them as the “penny photograph,” and street photographers became commonplace sights in towns, cities, and at resort areas such as Brighton, England, and Atlantic City, New Jersey, and also at carnivals and fairs. Tintypes were extremely popular during the U.S. Civil War when soldiers wished to have a picture made of themselves in uniform with their rifle or sword to send home to loved ones. Since a tintype is an image made on metal instead of on a glass plate, it could be mailed without concern for breakage. There is no “tin” in a tintype; it actually is a thin sheet of black iron. The original name for the tintype was melainotype, but the more common name is ferrotype, which refers to the ferrous (iron) base on which the image is recorded. It has been suggested that the term “tintype” was derived from the use of tin sheers used to cut and trim the images on the metal plates. Many tintypes will be irregular in shape, because of the imprecise trimming work. It is possible to narrow the dating of tintype photographs produced during this extensive period based on a number of criteria, especially in the United States:

• 1856–1860 The iron plate stock used in this period is thicker than at any other time, and plates are typically stamped on the edge with “Neff’s Melainotype Pat 19 Feb 56.” They may be found in gilded frames reminiscent of those used with ambrotypes or in leather sleeves.

• 1861–1865 During the Civil War years, their paper display sleeves may help to date tintypes. These “frames” may bear patriotic symbols such as stars and flags, and early ones bear the imprint of Potter’s Patent. After 1863, the paper holders became fancier, with designs embossed into the paper holder rather than printed. In an effort to raise revenue to help fund the Union Army, the U.S. Congress imposed a tax to be collected on all photographs sold between 1 September 1864 and 1 August 1866. A revenue stamp was required to be adhered to the reverse side of the photograph, either on the photographic plate itself or in the case. The tax was based on the amount of the sale, and these revenue stamps are highly prized by stamp collectors. Some photographers initialed the stamps to cancel them and included the day’s date and this provides a precise date for the completion of the sale of the photograph.

• 1870–1885 This period is referred to as the “Brown Period” because one company, the Phoenix Plate Company, introduced a ferrous plate with a chocolate-tinted surface. Soon photographers across the United States were clamoring to use this new style of plate. You should also know that photographers began using painted backgrounds reflecting a “country” look, with fences, trees, stones, and other rural images, in this time period. The painted rural background in these photographs is a telltale indicator that the photograph was made after 1870.

• 1863–1890 Photographer Simon Wing patented a multiplying camera that captured multiple images on a single plate. These photographs measured approximately .75″×1″ and became known and marketed as “Gem” or “Gem Galleries” photographs. These tiny portraits were typically mounted in ovals and attached to a larger mounting card. Some were even cut to fit into pieces of jewelry, such as lockets, cameo frames, cufflinks, and stickpins.

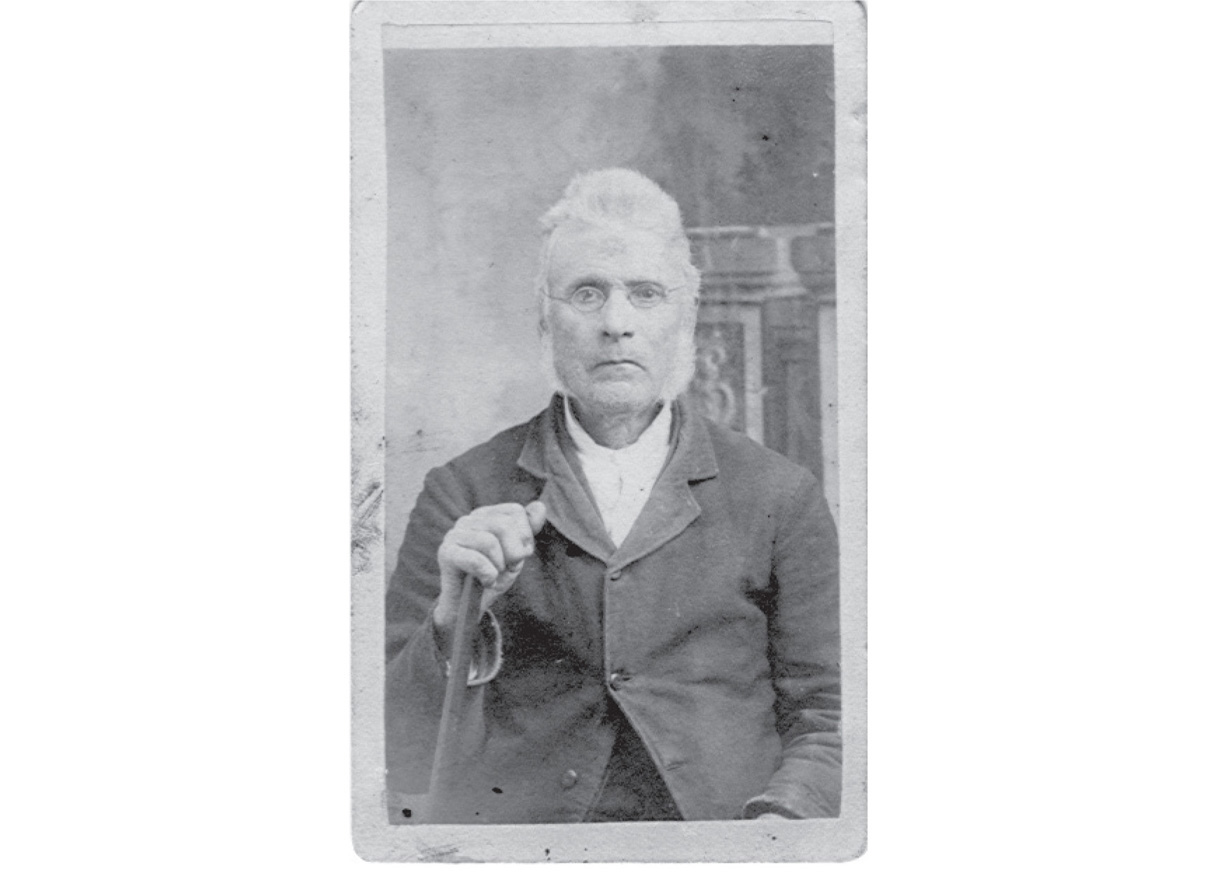

• Circa 1866–1906 A new method of mounting photographs was introduced and is referred to as the “cabinet card.” The photograph was adhered to a piece of cardboard stock. Early cabinet card stock is rather plain, with designs printed on the card. The type and color of the card stock and its decoration changed over the years, with embossed designs, colored inks, beveling, gilded or silvered card edges, and scalloped corners and edges being used at different periods. Photograph mountings were a point of high fashion, and you can use these distinctive traits, card sizes, and card thicknesses to date the period in which the photograph was made. The example shown in Figure 14-3 can be dated by the card stock to the period between 1880 and 1890 because the card stock is quite heavy, the front and reverse sides are of different colors, and the front surface is textured, rather than smooth. The woman’s hairstyle indicates a bun worn high in the back. The not-so-high collar, the ornamental pleating on the shoulders of her dress, and the detailed, raised embroidery along the neckline and down the front of the bodice are indicative of fashion three to five years prior to the explosive couture of the 1890s.

• At the same time that cabinet cards were being used, other sizes and styles of photographic mountings came into use. One very popular format was a smaller mounting referred to as the carte-de-visite, or visiting card. These cards, like the example shown in Figure 14-4, typically measured 4 1/4″×2 1/2″ and were made of heavy, often glossy card stock. They became the rage and were used as souvenirs and, true to their name, were left as calling or visiting cards.

• Other popular styles and sizes included the Victoria (5″×3 1/4″), the Promenade (7″×4″), the Boudoir (8 1/2″×5 1/4″), the Imperial (9 7/8″×6 7/8″), the Panel (8 1/4″×4″), and the stereograph (3″×7″).

• The stereoscope became a tremendously popular form of entertainment and education, beginning in approximately 1849 and continuing until the mid- to late-1920s. The apparatus consisted of a viewing hood with two lenses and an attached arm on which a sliding holder was mounted. The stereoscope was used to view stereographs such as the one shown in Figure 14-5, which depicts destruction following the San Francisco earthquake of 18 April 1906. A stereograph is a card on which two almost identical photographs are mounted side by side. When viewed with the stereoscope, the effect is that of a three-dimensional view of the subject. Tens of thousands of stereographs were made for the huge consumer demand for more and more subjects. In fact, you might draw an analogy between the stereograph and a modern television/DVD setup. People could not seem to get enough of them. Subjects included Civil War battlefields and scenes, world travel photographs, public figures, expositions such as the St. Louis and Pan-American Expositions, Americana, African-American subjects, children’s games and antics, costumes, cemetery tours, and even series of stereographs telling a story.

• Circa 1889 to Present Photography historians argue about who invented photographic film. However, an Englishman named John Carbutt, who also was an accomplished stereographer living and working in the United States, is credited with coating sheets of celluloid with a photographic emulsion while working in Philadelphia in 1888. In that same year, George Eastman introduced a new camera called the Kodak that used a roll of photographic film. The camera with the film still inside was sent to his company for processing, and the camera and a new roll of film were returned to the customer. Within a year, the Kodak name was a household word in the United States, Great Britain, Canada, France, and elsewhere, and the public was hooked on photography. People even had a choice of the way photos were printed, including as a face side for a postcard.

• Over the years, several film base materials and a number of emulsion processes were used, each having specific attributes. You can learn more about 20th-century photography and fashions in books on the subjects and on the Internet.

FIGURE 14-3 This photograph of the author’s great-grandmother, Ansibelle Penelope Swords Holder, was taken circa 1885.

FIGURE 14-4 A typical carte-de-visite

FIGURE 14-5 A stereograph looking east from the intersection of Ellis and Jones Streets in San Francisco, California, following the devastating earthquake on 18 April 1906

You probably never knew there was so much to learn about photographs, did you? One of the best books on the subject of dating photographs is Maureen A. Taylor’s Uncovering Your Ancestry Through Family Photographs.

Don’t overlook the fact that clothing and hairstyles shown in photographs can be very important research clues. Studio photographs were often made with the subject wearing his or her very best clothing, sometimes purchased specifically for the occasion. A photograph of a woman wearing a dress with a wasp waist and balloon sleeves, mounted on a cabinet card with a buff-colored, matte front and a dark-gray back, with gold beveled edge can be dated to within a year or so of its creation date. Examine the paper stock or card stock for a printed or embossed studio name (and location), which helps to narrow the focus of your genealogical search to a time and place.

Be sure to examine photographs for tiny details that might yield clues. Pay attention to buildings, signage, the presence or absence of electric and telephone wires, the styles of wagons and carriages, the sizes of trees and shrubs, and every detail that might communicate location and time period. Look at military insignia on uniforms, name badges or sewn-on patches, and other clothing details. Researching an old photograph is much like reading between the lines in a book. Enlarge and enhance photographic images to bring out details.

An excellent book on the subject of fashions over the centuries is Out-of-Style: A Modern Perspective of How, Why and When Fashions Evolved, by Betty Kreisel Shubert (Flashback Publishing, 2013), which contains hundreds of illustrations and descriptions of clothing fashions. The book can be used to help you identify the time period during which a photograph was made.

You can also search the Internet using general phrases such as “history of photography” or “costume history” or conduct more specific searches such as “Victorian clothing”; “women’s dresses” + 1830s; history + “men’s clothing” 1860s; or other combinations of keywords and/or phrases. There is a wealth of information available to help you narrow the date and place of your photographs.

Sometimes, despite all your research, analysis, and troubleshooting efforts, an ancestral brick wall will just be entirely too contrary. Every effort at direct research may be thwarted. What can you do now?

One of my favorite techniques is what I call “Sidestep Genealogy.” This can be comparatively simple to perform, and involves locating another close family member and switching your research focus. There have been times when I have encountered a brick wall in my research for one person and could not progress to the next generation. What I do then is review all I know about the person through compiling an ancestor profile. If I can identify a sibling or some other blood relative, I move to that person and begin conducting detailed research. I often have found that, while my ancestor may not have left a very good paper trail, his or her brother or sister may have. As a result, by researching a sibling, I have sometimes been able to trace the sibling’s parents and then, from one or both parents’ records, have been able to make the connection downward to my own ancestor.

If you cannot locate or identify a sibling to use in your research sidestep, look for another relative such as an aunt, uncle, cousin, and so forth. If you can identify one person as a focal point, you may just be able to blaze a new research path, albeit sometimes convoluted, up, down, and across the family tree, to locate the link that can then be connected downward to your own ancestor.

It may seem intuitive but genealogists often overlook the services that can be obtained from librarians, archivists, museums, and all types of societies. Librarians and archivists are among my favorite people. They are intelligent and have a nearly unquenchable thirst for knowledge. They love to research interesting and difficult questions and to provide help and instruction to their patrons. These unsung heroes of our communities are trained and skillful professional researchers. They may not know where my great-grandmother Penelope Swords Holder was born, but they know how to employ their research skills, techniques, and tools to help me locate print and electronic reference materials.

If I have a particularly impossible question about the location of a place that no longer appears on any map, I certainly try to search the materials at my disposal. That includes my own collection of maps, atlases, and gazetteers; online databases and map collections; and any possible Internet resource that I am creative enough with search terms to locate. After my own exhaustive searches, however, I have been known to contact an academic library with a good map collection, a state library or archive, and even the cartographic division of places like the Library of Congress, the National Archives and Records Administration, the National Geographic Society, and The National Archives in the UK. The staffs at these places are experts in locating this type of information and are always willing to help.

I encourage you to join genealogical societies in the places in which your ancestors lived and where you are conducting research. The cost is comparatively small but the benefits can be great. The publications of these societies, such as journals, magazines, and newsletters, often contain articles that provide contextual insight about your ancestors’ lives and the events in the area. A genealogical or historical society may have conducted a project to identify, document, or otherwise produce a compendium of names, locations, or events in a specific area. They may even have published some or all of the information in a book or journal, but other materials may not yet have been made publically available in any widespread way. These materials may significantly extend your research. In addition, there is the opportunity to connect with other researchers who might be researching your family or connected collateral lineages.

Genealogical and historical societies are excellent resources to assist in your research. Even if you are not a member, you may still make an inquiry of such a group to request information. The society can check its own collection of information and reference material and respond with information for you. Often, too, a society member will make an extra effort to help by heading to a local library, courthouse, government office, cemetery, or other facility to do a quick look-up for you. These “genealogical angels” perform extraordinarily kind services, and while it often is not expected or requested, I always offer to reimburse the person for the cost of their mileage, photocopies, postage, and other expenses. Don’t overlook the Federation of Genealogical Societies (FGS) at http://www.fgs.org and the New England Historic Genealogical Society (NEHGS) at http://www.americanancestors.org in the United States, and the Federation of Family History Societies (FFHS) at http://www.ffhs.org.uk in the United Kingdom as resources to help connect you to important organizations and resources in their areas.

Heritage and lineage societies are another excellent source of information. Their staffs and members often maintain extensive collections of printed materials, as well as genealogical records and data submitted by members. These people are experts in genealogical problem solving and know how to address difficult questions and help find answers to obscure facts. There are scores of different such societies, many with regional chapters, lodges, or branches.

You may also determine that your ancestor or another family member was a member of a particular professional, fraternal, trade, alumni, or similar membership organization. If so, consider locating their headquarters and inquiring about any records that may exist about your ancestor, a website where those records might be located, and how to proceed to request them. Almost all of these organizations will have a website that you may locate using an Internet search engine.

All of these entities exist to serve their members, and their membership operational staffs may be able to help you locate information on your ancestor. They provide yet another resource to help you locate information to get past your brick wall.

There may come a time when you simply cannot get past your most stubborn brick wall. After trying everything you can think of and following every link you can discover, you may realize that you need the help of a professional genealogical researcher.

A professional genealogical researcher can help you in one of two ways. First, he or she can perform research for you on a fee basis, or second, he or she can act as a paid consultant to you and provide guidance and advice. Before engaging a professional, it is important to identify one who is qualified to provide the service(s) you wish performed, reach agreement on the scope of the work, and define the guidelines that will govern the arrangement.

Anyone who has experience in genealogical research can assist and advise you. However, your best guidance will come from an individual who has been professionally trained and/or has successfully passed tests administered by a professional genealogy credentialing body. There are a number of organizations whose genealogical credentialing standards are held in high esteem. Let me share some of those with you, along with their websites at which you can learn more.

The Association of Professional Genealogists (APG) is not an accreditation or credentialing body, per se. It is, instead, a membership organization consisting of more than 2,000 members in the United States, Canada, and 20 other countries whose primary purpose is to support professional genealogists in all phases of their work, from the amateur genealogist wishing to turn knowledge and skill into a vocation, to the experienced professional seeking to exchange ideas with colleagues and to upgrade the profession as a whole. Headquartered in Westminster, Colorado, the association also seeks to protect the interests of those engaging in the services of the professional. Their website at http://www.apgen.org presents a good primer at their link labeled “Hiring a Professional,” located under the Publications menu. In addition, the site contains a searchable database of all current APG members, their titles and/or certification, organizations with which they are associated, and their area(s) of expertise or specialization.

The Association of Professional Genealogists in Ireland (APGI) acts as a regulating body to maintain high standards among its members and to protect the interests of clients. Its members are drawn from every part of Ireland and represent a wide variety of interests and expertise. Applicants are required to submit samples of their work in the form of a report on research conducted over a period of not less than five hours, exclusive of report preparation time. The association’s website is located at http://www.apgi.ie.

The Board for Certification of Genealogists (BCG) is an independent, internationally recognized organization headquartered in Washington, D.C., that certifies qualified individuals in the field of genealogy. They define their mission as follows: “To foster public confidence in genealogy as a respected branch of history by promoting an attainable, uniform standard of competence and ethics among genealogical practitioners, and by publicly recognizing persons who meet that standard.” Certification involves preparing a portfolio of materials, which is independently reviewed by a panel of three or four judges. BCG requires different materials for each of the following certification categories (the credential designations are shown in parentheses):

• Certified Genealogist (CG)

• Certified Genealogical Lecturer (CGL)

BCG has published the BCG Genealogical Standards Manual, which details the requirements for certification in each category. Certification is for a period of five years, after which time the researcher may apply for renewal of his or her certification.

The BCG website at http://www.bcgcertification.org maintains a current roster of certified individuals, searchable by where they are located and by special interests (Irish, English, Jewish, African-American, church records, and more).

The Genealogical Institute of the Maritimes (Institut Généalogique des Provinces Maritimes) is a nonprofit organization that examines and certifies persons wishing to establish their competence in the field of genealogical research. The first level of certification is that of Genealogical Record Searcher [Canada] [GRS (C)]; the second is that of Certified Genealogist [Canada] [CG (C)]. By completing a preliminary application form that assigns points for education, genealogical research experience, and publication, a candidate is evaluated through a points system to determine if he or she possesses the qualifications required to apply for certification at either of these two levels. More information is available at their website at http://nsgna.ednet.ns.ca/gim.

The International Commission for the Accreditation of Professional Genealogists (ICAPGen) is a professional credentialing organization that is involved in testing an individual’s competence in genealogical research. Originally established in 1964 by the Family History Department of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS), the program was transferred to ICAPGen in 2000. At the time of the transfer, ICAPGen was affiliated with the Utah Genealogical Association (UGA).

Each applicant for the ICAPGen Accredited Genealogist (AG) credential must demonstrate through extensive written and oral testing, and through production of high-quality, well-researched documentation, that he or she is an expert in a particular geographical or subject area. The current areas of geographical testing are the United States, the British Isles, Scandinavia, Canada, Continental Europe, Latin America, and the Pacific Area. You can learn more about the specific countries and regions included by visiting the ICAPGen website at http://www.icapgen.org.

The ICAPGen website also provides a database of accredited researchers, searchable by name, their place of residence, or area of specialization. PDF files of North American and International researchers are also available for printing.

Individual genealogical researchers may have been awarded other credentials than those previously listed. Some colleges and universities offer courses in genealogical studies, and there are any number of specialized genealogical lecture programs and institutes offering individual classes or immersion conferences. These all may entitle the student or attendee to receive the award of a certificate, diploma, or another document attesting to his or her successful completion of the curriculum. These may be weighed in your decision-making process to determine if an individual has the education, experience, and expertise to perform the service(s) you require.

Once you decide which professional researcher you want to hire, he or she will likely ask you to define exactly what you are seeking. You should prepare a written report on the individual or family group for which you want research performed, and provide all the information you have gathered. Include names, dates, and source materials you have located, and a description of each item’s contents. Here is where an ancestor profile can really come in handy. What you are doing, in effect, is preparing for your potential researcher a complete picture of what you know.

Once that is prepared, you must decide what it is you want to know, and what you want the professional researcher to find for you. These two items may not be one and the same. For example, you may believe that identifying the parents of one ancestor may be all you need in order to continue your research beyond that point.

On the other hand, you may decide that you want the researcher to accept the commission and pursue your research farther. For example, you may have traced your ancestors back to a point at which they arrived from another country or continent, and you want the researcher to first locate the passenger arrival records to determine their port of departure, and then to trace your ancestors back to their native town or village.

It is important to be precise in determining the goal or goals of your research. Your goal(s) will determine the scope of the work to be performed, and you should also define the scope in writing. This document complements the documentation of your research to date, that is, the ancestor profile.

The professional researcher will now be able to review your research materials and evaluate the scope of your project goals. Request a written research plan, an itemized estimate of research time and expenses, a reasonable timetable for the project, and a list of project deliverables. For example, the researcher may determine that locating your immigrant ancestors’ passenger arrival may take 15 hours’ work, tracing the ancestors to their native village may take another 30 hours’ work, and preparation of the final report may take another 5 hours’ work, a total of 50 hours’ work. In addition, costs of document copies, photocopies, telephone calls, postage, mileage, travel, lodging, and meals may be itemized to present an itemized grand total. A good researcher will generally offer you a list of references, and may provide a sample of a final report to give you an idea of the quality of the final product you would receive.

Take your time to review the researcher’s proposal and weigh the expenses against what it might cost you in time and money to perform a similar job. Contact the references the researcher provided and discuss their experience with the researcher. Describe at a high level to each reference what it is you want the researcher to do for you, and ask if the person believes the researcher could and would be able to satisfy your need. Take notes and prepare additional questions for your potential research candidate.

Schedule a time to meet with or talk by telephone with your researcher about any questions you have. Make sure that they are all answered to your satisfaction. At that time, consider all the information you have at hand and make your decision. Investing in a professional researcher’s services is much like buying an automobile. It pays to do your advance research and to shop around as necessary for the right researcher. Requesting proposals from two or more researchers is not a bad idea. This advance work may save you money and frustration as the project progresses.

Let’s say that you have decided to accept the proposal of one professional researcher. The association between the two of you should be a formal contractor-contractee relationship. As such, it should be documented in the form of a contract. A good contract will detail the scope of the work. It also will specify the exact amount of time the researcher will spend and the precise amount of money that you authorize for the project. Be sure to establish benchmarking milestones in the project schedule. These facilitate communication of status reports from the researcher so that you know what is happening. It will help alleviate surprises later on and will allow you both to determine early on whether the scope and goals of the project need to be adjusted.

The contract should include payment terms, and it is not unusual to use a graduated payment schedule. For example, you might choose to pay 25 percent of the total fee as an advance before the project commences; incremental payments payable at certain milestone points, such as written status reports or some mutually agreeable criteria; and the remainder as a final payment when the final report and documentation are delivered. Include a contract cancellation clause that protects your and the researcher’s interests.

A good contract is mutually acceptable to both you and your researcher. It should be designed to provide legal protection for both of you. With the project goals and deliverables clearly defined, and the authorized expenses clearly itemized, your expectations and those of the researcher are set.

When the research project is completed, and you have received your final report and accompanying documentation, make time to read and study its contents. Prepare a list of any questions you have about the contents or outstanding issues. At that point, you should schedule and conduct a final recap meeting with your researcher. Discuss the report and any questions you have about it, the documentation, the source materials found, where they were located, the source citations, and any other pertinent issues. You may learn a great deal from the researcher’s recounting of the research process, including information that he or she may have encountered about other individuals that is not included in the report. These may be leads that you can pursue on your own at a later date.

If your experience with your professional researcher has been a positive one, you can offer to be a reference for his or her future clients’ inquiries. In the event that the experience has been problematic or the researcher has not performed in a professional or ethical manner, you should consider contacting the certifying or regulatory body that awarded his or her genealogical credentials and file a formal report. This action will help the organization keep track of problems and consider them when reviewing the renewal of the individual’s certification or continuation of accreditation. It also helps protect other genealogists from an unsatisfactory researcher.

You will find that professional genealogical researchers are eager to help you and subscribe to a code of high professional ethics and behavior. Seeking out a credentialed individual with the qualifications and experience in the field of specialization you require is a solid first step to getting what you want from a professional research experience. Carefully setting the goals and establishing the contractual relationship with your researcher is essential. You can encourage the progress of the project by establishing and following up on the milestone status reports along the way.

All of the methods and resources discussed in this chapter should make you feel more confident about the various research routes you have open to you. Difficult-to-trace ancestors will invariably show up in your family tree. However, as long as you know how to conduct scholarly research, learn about and work with all kinds of alternative records, and employ the strategies and methodologies defined here, the chances are excellent that you can knock down those brick walls and keep moving your genealogical research forward.

Be prepared for research brick walls to appear anywhere and at any time. A roadblock may occur because of a lack of evidence, spelling and transcription errors, multiple people in the same area with the same name, and a wide variety of other reasons. Let’s look at a few examples to give you some ideas of possible solutions.

The person’s parents cannot be identified or traced. This is perhaps the most common brick wall genealogists face. Moving backward one more generational step can be exceptionally challenging.

Possible Solutions Search for ecclesiastical records for your person that may indicate previous membership in another congregation elsewhere. I was able to trace one of my grandfathers from the church in North Carolina in which he was a member at the time of his death back to the church in which his family were members in Georgia, then back to another church in Alabama, and finally to the church in Tennessee in which he was christened. That church’s membership roll also included his parents’ transfers of membership from other churches, thus directing me to those churches for their families. Another possible solution, discussed in detail earlier in the chapter, involves researching one or more other family members.

The person’s previous place of residence cannot be identified or traced. This is perhaps the second most common brick wall genealogists face.

Possible Solutions The ecclesiastical membership record search could work here as well. Common alternative records to help locate previous places of residence include voter registration records, school records, census indexes and population schedules, immigration and naturalization documents, land and tax records, probate packet inventories and heir lists showing property ownership and/or the residences of heirs in other locations, military service records, and obituaries.

The records you wanted or expected to find are missing, lost, or have been destroyed. Records do disappear, sometimes through misfiling and sometimes by having been removed or stolen. A common problem, too, is that the courthouse or other repository burned at some time and the records were lost. Consider my dismay to find evidence of an ancestor’s considerable estate documented in probate court minutes, only to find that the entire probate packet was not in the probate clerk’s files. The will and the executor’s/administrator’s documentation could have provided definitive proof of the names of my ancestor’s children and whether they were living or deceased at the time of his death. It also could have identified other relatives, land and property holdings, and other pointers to other documentation.

Possible Solutions Locate all the probate court minutes for hearings concerning the estate. Some of the probate file materials may actually have been read into evidence in the probate court minutes when the report was introduced. Seek newspaper announcements concerning the settlement of the estate. Determine the name(s) of the executor/administrator(s) of an estate through the use of probate court’s minutes, and then check the probate files in the event your ancestor’s packet was incorrectly filed under the executor/administrator’s name rather than under your ancestor’s or another family member’s name. In addition, it is not unheard of to find that a probate packet was removed by a lawyer or other representative and retained in that person’s professional files. Investigate the possible existence of transcriptions, extracts, or abstracts of the original will in books, genealogical society publications, and elsewhere. Contact libraries, archives, and genealogical and historical societies to determine if they are aware of the existence and/or disposition of the records you are seeking.

Some of the records you seek may actually have been microfilmed after they were separated, and your research may require that you reunite and reconstruct the different materials from different locations. Further, those records may have since been digitized and may be online at a county website, at FamilySearch, or on another commercial database site.

The records you are seeking have been discarded or destroyed. Perhaps the courthouse or other government repository ran out of space and determined that records older than a certain date were no longer needed. Originals of records may have been microfilmed and then destroyed, and then the microfilm might have been lost. There may have been a fire, tornado, hurricane, earthquake, flood, or other calamity in which the courthouse or archive was damaged or destroyed, and records were lost.

Possible Solutions Consider substitute records that might provide identical or similar information. Contact archives, libraries, and genealogical and historical societies that might have acquired or salvaged any records. Investigate the possible existence of transcriptions, extracts, or abstracts of the original materials made or published prior to the records’ loss. Don’t overlook the possibility that records could have been duplicated and sent/transferred to another agency. Tax lists are usually published annually in a newspaper. These may help identify land ownership for your ancestor from the time the property was purchased until the time it was sold or ownership was otherwise transferred.

Records were destroyed during a time of war. Contrary to what you may have heard, General William Tecumseh Sherman did not destroy every courthouse in his march through Georgia during the U.S. Civil War. However, some county government buildings and their records were lost. During World War II, there was so much bombing and fire damage in Antwerp, Belgium, that only a few pages of passenger lists survived.

Possible Solutions Look for possible duplicate or substitute records. Investigate the possibility that the records were copied or microfilmed prior to their loss, that transcripts were published elsewhere, or that indexes survived when the actual records did not.

There is no evidence the person ever lived in that place. Your research has pointed you to a specific place where, no matter what type of records you investigate, there are no records that your ancestor was ever there.

Possible Solutions Perhaps the lead you had was incorrect. Or maybe the governmental jurisdiction has changed and the records are really in another place. Be sure to check historical maps from the time period you believe your ancestor was there, and verify the correct jurisdiction. Stop and reexamine all of your information to look for clues you may have missed or information that may have been incorrect.

The names and/or dates are all wrong. I was searching for the origin of one of my great-great-grandfathers, Jesse Holder. I knew he lived in Georgia after he was married, but U.S. federal censuses indicated he was born in North Carolina. Searches of records in North Carolina yielded nothing, and so I transferred my attention to the possibility that he may have lived in South Carolina during some period. I found a Jesse Holder in Laurens County, South Carolina. Unfortunately, his year of birth didn’t seem to fit. I then was able to find evidence that this Jesse Holder had married another woman and that he had died prior to when my great-grandfather was born in Georgia. My own Jesse Holder had been born on 13 August 1810 in North Carolina, and the other Jesse Holder had been born well before his inclusion as a head of household in the 1790 U.S. federal census. My further research revealed that the Jesse Holder in South Carolina was, in fact, the uncle of my great-grandfather. He was the person after whom my maternal great-great-grandfather was named.

Possible Solutions Retrace the research steps to determine if you are on the right track or took a wrong turn. Look also in the same area for other branches of the same family that really might be yours. Naming patterns sometimes show that children may have been named for one of the parents’ parents, an aunt or uncle, or a sibling.

There is no discernible link between your ancestor and the people you think could be the parents, siblings, spouse, and/or other relatives.

Possible Solutions Examine census records in the area in which your person lived. Look for other persons in the vicinity with the same surname, and begin to research them. Examine obituaries, wills, probate records, and ecclesiastical records and look for any family relationship or common denominator linking them together. Examine land and property records to look for names of family members between whom property was bought, sold, given, or inherited. Consider cemetery records and monumental descriptions to help you relate persons to one another, and then conduct research on those people. Be alert to burials of individuals adjacent to one another that might infer family relationships, and be prepared to research these.

The person has just simply vanished into thin air. (I call this the “my ancestor was abducted by an alien spaceship” problem.)

Possible Solutions Reexamine census records for your ancestor and for the four to six neighboring families on either side of your ancestor. Locate your ancestor in the last census where you found him or her. Look, then, at the next available census for the neighbors. If they are all still in the same place and your ancestor is gone, you know you have looked in the correct place. If one or more of the neighbors also is gone, start looking for your ancestor and the neighbor in available census indexes in that location and surrounding parishes, counties, provinces, or states. Work in concentric circles, using a map and considering the migration routes and social trends of the time, and move outward seeking your ancestor in records that might likely have been created at the time. For example, if you know your ancestor was a Methodist, start looking at Methodist church membership records. Look for voter registration records if the period coincides with a major national election year. Check land and property records to determine if there was a change in property ownership—property sold, different property purchased, relocation to another location, or reference to the death of the property owner and the inheritance by an heir.

Don’t forget to look at census mortality schedules in the U.S. federal censuses of 1850 through 1880. If your ancestor died in the 12 months prior to the enumeration date of the census, he or she should be listed on the mortality schedule, along with his or her age, the reason for death, and other information.

Adoption records are sealed by a court and not accessible to the public.

Possible Solutions Formally petition the court in whose jurisdiction the adoption took place for access to names and dates of the parties. Be prepared to demonstrate your relationship to any and all parties. (Be sure to check the more recent legislation of the locations involved, as some of these adoption records are being made available, especially in the United States.)

The records you want are the property of a private corporation and you are refused access to them.

Possible Solutions Prepare evidence of your relationship to the person whose records you require and a solid reason for your request. Instead of access to the entire body of records, request an exact extract of the content you want to obtain. If you are refused, be prepared to escalate your request to the headquarters and/or executive officer(s) of the corporation. I have used this tactic in order to access personnel records and funeral home/mortuary records of individual family members.

These examples are not, of course, comprehensive in the scope of possible alternative sources and strategies, but they will give you some ideas to contemplate. Again, it is important to understand your ancestor in context, all of the record types that might have been created, possible repositories, and individuals and organizations that may be of help to you.

Do not ignore published case studies just because they do not specifically address your ancestors. There are many professional genealogists who write case study articles for publication in magazines and journals. These can be highly informative and educational because they illustrate how to approach research problems in a logical and methodical way. They typically start with a description or definition of the research problem in the question(s) that they want answered. Each research step is described in detail including: the type of record or alternative record being sought; the information expected to be found in each of these records; the place(s) where the record(s) might be found; how the records were accessed; whether this was an original or derivative record; what was actually found in the records, and how good was the information in it; which questions were answered and which ones were not; and what hypotheses or conclusions were drawn from the records. Case studies can be found in many professional journals, society journals, and commercial genealogy magazine publications. Carefully read these articles and study the documents used and the processes applied. You are guaranteed to learn a great deal from other people’s research.