It was Good Friday. Many had been to church or were going later in the evening. Easter was early this year, and throughout much of southcentral Alaska on March 27, 1964, winter still held the land in its cold and icy grip. Around the waters of Unakwik Inlet in the northwestern reaches of Prince William Sound, silence cloaked the mountainsides. Animals, some say, can sense impending natural disasters before they strike. If so, perhaps bald eagles took to the skies to shriek a warning, snowshoe hares looked around nervously, and sea otters paused in their incessant preening. Hibernating brown bears slept on—for the moment. The time was 5:35 P.M.

Alaska’s rim of fire is no stranger to earthquakes. Here, the grating forces of the Pacific and North American plates have long caused the earth to rumble, shake, and otherwise adjust itself. The town of Valdez, some forty miles east of Unakwik Inlet, has recorded dozens of major earthquakes and numerous minor ones since records were begun in 1898. By some counts, one out of every ten of the world’s earthquakes occurs in Alaska. But no one was prepared for the fury that was unleashed this March evening.

At 5:36 P.M., something snapped along the fault lines beneath the waters of Unakwik Inlet. The resultant shock waves spread in all directions—heaving islands upward, sucking lakes dry, and violently shaking ridgelines and valleys. For three to four minutes the rumbling continued. Registering between 8.4 and 8.7 on the Richter scale, Alaska’s Good Friday earthquake was the most powerful seismic event ever recorded in North America. In comparison, the 1906 San Francisco earthquake was a mere tremor.

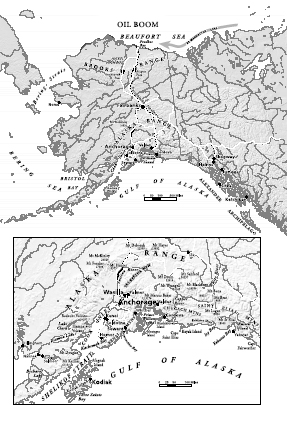

From the quake’s epicenter in Prince William Sound, major destruction spread across more than 100,000 square miles. The earthquake was felt throughout an area greater than 500,000 square miles—roughly twice the size of Texas. The change in the landscape was mind-boggling. Some areas in southeastern Prince William Sound rose as much as thirty-eight feet. In the northwest, land dropped an average of two to three feet, flooding beaches and inundating freshwater marshes with salt water. Some land areas shifted seaward as much as sixty-four feet.68

The natural scene was the setting, but it was only a part of the story. Human inhabitants were dumbstruck. Some thought the end of the world had come. Others were certain that despite the DEW Line, the Soviets had managed to drop nuclear bombs on Elmendorf Air Force Base. Strictly in terms of power, that would have been mild by comparison. By one calculation, the earthquake unleashed 200,000 megatons of energy—more than 2,000 times the power of the mightiest nuclear bomb then in U.S. arsenals. Most folks were simply too shocked to reason beyond immediate fears for their own safety and that of their loved ones.

At his house overlooking Turnagain Arm south of Anchorage, J. D. Peters walked into the driveway to greet his wife, who was just coming home. Before he could hug her, the earth opened and the two were separated by a gaping fissure. Peters tried desperately to throw his wife a line to keep her from slipping down the slope. Just as suddenly, the fissure closed back up, and she was propelled into his arms. Throughout the surrounding neighborhood there were frantic screams and outcries as houses broke apart and dumped their occupants—some barefooted, others holding babies—out onto buckling streets and sliding hillsides. Peters dashed into one crumbling house and gathered coats and boots for those fleeing into the cold.69

In another section overlooking Turnagain Arm, the house of Lowell Thomas, Jr. dropped like a rock when a large portion of bluff gave way. Mrs. Thomas and their two young children managed to escape and gamely climb up to level ground through a maze of shattered buildings and slippery, snow-covered slopes. Later, waiting at their minister’s home to be reunited with Mr. Thomas, they heard the calm voice of the KFQD radio announcer matter-of-factly report that as far as he knew, little actual damage had occurred. “Wait till he sees our street!” eight-year-old Anne Thomas exclaimed. Two neighborhood children were not so fortunate. Twelve-year-old Perry Mead shepherded two younger siblings to safety and then returned to his house for his baby brother. Neither was ever seen again.70

Joe Kramer, a veteran Anchorage taxi driver, had seen a lot of crazy driving in his time—alcohol-inspired and otherwise—but when vehicles started fishtailing toward him like bumper cars at some Midwest amusement park, he thought that their drivers had gone berserk. “It was when they started bouncing two feet off the ground,” recalled Joe gravely, “that I knew it was more than just the drivers.”71

Downtown Anchorage looked like a war zone. At the first rumblings, attorney Russell Arnett burst out of the Anchorage Athletic Club’s steam bath and started running down Fourth Avenue—stark naked. Other souls tumbled or crawled out of collapsing structures and quickly formed a human chain to keep from falling into dozens of yawning fissures. Arnett joined the chain. No one, not even Arnett, seemed to notice that he was missing his clothes.72

Along the north side of Fourth Avenue above Ship Creek and the Cook Inlet tidal flats, the ground sank some twenty feet. Restaurants, bars, liquor stores, and pawnshops disappeared from sight. Most of the Denali Theater sank below street level. Only its neon sign, remarkably intact, remained completely above ground. But just across the street on the south side of Fourth Avenue, buildings suffered only minor damage and a few broken windows. Ironically, a banner advertising the Alaska Methodist University’s production of Thornton Wilder’s Our Town—a play without scenes or sets—still spanned the street.73

The quake’s selectivity along Fourth Avenue was repeated elsewhere. Half of a floral shop was gone, but in the remainder, arrangements of Easter lilies stood tall and serene in their vases. The walls of the year-old J.C. Penney store collapsed outward, killing a pedestrian who had crouched beneath them and a woman in a passing car. A few blocks away, the fifteen-story Anchorage-Westward, the city’s largest hotel, stood unscathed but surrounded by rubble. At the airport, the control tower collapsed, killing a controller, but the terminal building was largely untouched.

All too quickly, darkness fell. Without electricity, heat, or running water, the town hunkered down as temperatures dropped into the teens. As the town slowly dug out in the days that followed, William DeAngelis summed up what a lot of people were thinking. Cradling his little dog—the only thing that he had left—on his lap in one of the relief centers, the old man shook his head and softly sighed, “I’m just settin’ here with Beauty, waiting for my social security to come. I don’t have anyplace to go.”74

Miraculously, out of a population of 55,000, there were only nine deaths in Anchorage, but it was a different story out on Kodiak Island and in Seward, Valdez, and the little village of Chenega. The surface rumblings were relatively minor compared to the quiet horror of the killer tsunamis that struck soon afterward. Underwater landslides and water displacements caused by seaward movements of land built huge waves and sent them rolling across Prince William Sound and the Gulf of Alaska at speeds approaching 500 miles per hour.

Anchorage braced for a tsunami, but it amounted to only three feet. The town was spared any more major damage in part because much of it was about 100 feet above sea level. The towns around Prince William Sound, however, weren’t so lucky. A monster seventy-foot-tall tsunami roared through Knight Island Passage and inundated the little village of Chenega. Many of its twenty homes were built on pilings. When the first wave swept through, it picked the structures up and carried them away like pieces of driftwood. Twenty-three of the town’s eighty inhabitants drowned, thirteen of them children. Only the schoolhouse high on the bluff above the village remained undamaged. Here, school should have been in session.

And Valdez? Well, Valdez was just about gone. Earlier on Friday afternoon, the Alaska Steamship Company’s Chena, fresh from Seattle, had cruised into Port Valdez and tied up at the town dock. The arrival of the regular supply ship was a popular event, and some of the townspeople were on the long dock watching longshoremen unload her cargo. Among them was twelve-year-old Freddie Christofferson. When the rumbling started, Freddie’s companion yelled, “Earthquake!” and took off running. Freddie followed close behind, but when he looked back over his shoulder, he saw the Chena picked out of the water as if she were a bathtub toy. All of her mooring lines snapped. Water swept over the dock, and the ship slammed into it with a bone-jarring blow that disgorged a fusillade of exploding timber. Some of the ship’s crew were trapped belowdecks by shifting cargo.75

The Chena’s captain gave three blasts on the whistle and attempted to navigate to the presumed safety of the middle of the harbor. By some counts, the ship bottomed three times as the waves rolled back and forth. As the water flowed seaward, some said that it was as if a giant bathtub were draining. When the water reversed its course, the torrent piled up in the shallows into a giant wave that broke across the dock and swept away dozens of people. In all, thirty people drowned in the tsunamis that steamrollered across the town’s tidal flat.

The longshoremen who had been on board the Chena unloading the ship demanded that the captain return to the splintered dock and put them ashore. When he refused, they piled into a lifeboat and rowed to the beach through a jumble of unpredictable waves, swirling debris, and jagged ice. Somehow, the Chena managed to stay afloat.

On shore, fuel tanks ruptured and soon caught fire. Teenager Helen Irish, who just minutes before had been among those on the dock, cried hysterically as her father left their house to search for her mother. Slowly, most survivors struggled toward higher ground. Many spent the night in the freezing cold high on the slopes of Thompson Pass. They looked down on the ruins that had once been their town, but that now were illuminated only by the fiery glow from blazing oil tanks.

The following morning, many survivors were taken north on the Richardson Highway to Glennallen. There, Helen Irish, still frantic with worry, found her mother safely asleep on an army cot. Others weren’t so lucky. One old woman labored painstakingly to fill out the hauntingly yellow Western Union forms that would notify relatives that her husband had been one of those swept out to sea. Because the ground was either still frozen or flooded, other casualties were committed to the deep waters of Port Valdez for burial.

It was much the same in Seward. The afternoon had been dead calm—a rarity without the winds that alternated between the Harding Icefield and Resurrection Bay. Able-bodied seaman Ted Pederson was checking valves on the fuel lines between Standard Oil’s bulk storage tanks and the tanker Alaska Standard—in those days still delivering oil to Alaska. Pederson felt the dock tremble and knew what was happening. “Earthquake!” he yelled, and ran toward his ship just as the dock rose ten feet into the air. The hoses parted and gasoline sprayed in every direction. As the dock fell downward, a giant wave laced with timber and debris swept over Pederson. But he, too, was one of the lucky ones. When he regained consciousness, he was aboard his ship with nothing more serious than a broken leg.

Lenny Gilliland watched as the bulk storage tanks and the Alaska Standard seemed to disappear from sight. In their place appeared a huge fireball fed by the wildly spewing gasoline. It looked to Gilliland as if all of the water had suddenly gone out of Resurrection Bay. Gilliland couldn’t be sure, but if that was even partially true, he knew that it would return in a big way. As soon as the wild shaking stopped, Gilliland gathered his family into the car and headed for higher ground.

The gasoline from the broken lines on the Standard Oil dock stoked a water-borne inferno in the bay. The Alaska Standard plowed through the fiery waters in an attempt to get away from it. Then came the first tsunami. Later, no one could agree on how many there had been, how long after the quake they struck, or how tall they were. But their impact was undeniable. The first wave lifted a wall of fire from the bay and pushed it inland over the Texaco tank farm eight blocks from the waterfront. Water and burning fuel surged across the railroad yards, setting fire to dozens of homes, trailers, waterfront shops, and even the radio station.

Dorothy Horne was alone in her house that doubled as the Railway Express office. She was reading the J.C. Penney catalog when the house started to shake. Remembering that one was supposed to stand in a doorway during an earthquake, Horne did so until the shaking got so bad that she finally stumbled outside. “I remember seeing a train coming down the tracks,” she later recalled. “The harbor master had a house right over there. It started falling into the water. Then I saw the boats in the small-craft harbor—it looked like they were trying to climb on top of each other. I looked back where the train was and it was gone.”76

All night long, flames from the oil tanks lit the sky while the occasional explosion of another storage tank punctuated the stunned silence. Then there was another eerie sight. The pilings from the exploded docks floated in the waters of Resurrection Bay with their waterlogged portions submerged and their relatively dry, tar-and oil-encrusted ends above water and now aflame. These burned like candles and made for a flickering procession of torches as they bobbed with the tide out to sea.

Seward had been scheduled to receive an All-America Cities Award for its industrial and civic improvements. When a reporter offered his sympathies in the face of such a calamity, one Seward resident shrugged and said, “That’s all right. That bay out there and the pass behind the town aren’t named Resurrection for nothing.”77

Kodiak was farther away from the quake’s epicenter than either Seward or Valdez. It shook less but was subject to the full brunt of the tsunamis that raced across the Gulf of Alaska. When Karl Armstrong, editor of the weekly Kodiak Mirror, felt the first tremor, he thought that he had a story. Walking during the quake was like marching across a field of Jell-O. But when Armstrong couldn’t reach Anchorage by telephone, he quickly realized that, far more than a story, he had a disaster in the making.

The first tsunami on Kodiak sneaked in quietly—a fast surge of rising water that had no wave crest. Off-duty navy lieutenant Raymond Bernosky was climbing a small hill to tend some traps when he happened to look back to where he had parked his Scout several hundred yards from the beach. The vehicle was suddenly afloat and coming toward him. Studded with floating ice, the waters swept swiftly and silently up the hill and chased Bernosky to higher ground.

Down at Kodiak Harbor, Captain Bill Cuthbert was eating dinner in the galley of his fishing boat, Selief. When he felt the eighty-six-foot-long vessel shudder sharply, his first thought was that some greenhorn had rammed him. By the time Cuthbert got on deck, the surrounding 160 crab and salmon boats in the harbor were bucking at their moorings like wild broncos. Then the first wave retreated, and the sea level in the harbor dropped. Cuthbert figured that he could ride out whatever followed.

The second wave hit with a much wilder vengeance, pushing a crest as tall as thirty feet. Townspeople who had not already done so scurried up Pillar Mountain. Captain Cuthbert stayed with his boat. The wave picked up the small boats and tossed them inland at least two or three blocks. Some, including the Selief, rode the wave back out as it took an assorted collection of buildings with it. Later when they could laugh again, townspeople would joke, “Come to Kodiak to see the tide come in and the town go out.”

The enormous waves continued. Again, the details of how many, how high, and how often were lost in the blur of the night. Cuthbert rode several waves in and out and then ended up aground several blocks inland. The port radio operator was frantically contacting boats, and when she got to the Selief and queried her position, Cuthbert drawled, “By dead reckoning, in the schoolyard.”78

When the waves at last subsided, Kodiak was a shambles of splintered buildings and broken water lines squirting geysers into the air. Most of its fishing fleet lay in a heap, with holes in their hulls and masts and rigging hopelessly entangled. On average, Kodiak slumped five feet. Everyone pitched in to help with the cleanup. One resident couldn’t resist telling city manager Ralph Jottes, “I wished you every success when you campaigned to clean up Kodiak, but this is ridiculous.”79 Elsewhere on the island, tracks showed that many of the island’s famed brown bears had awakened in a hurry, and rather than wandering around as would be their norm after hibernation, they had made a beeline for the ridgelines.

As bad as the earthquake was, it could have been worse. A total of 115 Alaskans died, and 4,500 were left homeless throughout the state. Another 16 people drowned in tsunamis along the Oregon and California coasts. But the fact that the quake struck on a holiday, and at an hour when many were at home, no doubt eased the death toll. Crowded schools and downtown areas, particularly in Anchorage, might have resulted in many more deaths. At one Anchorage school, an entire wing dropped a dozen feet into a fissure-laced pit, and the roof collapsed on much of the school’s other wing. In many respects, it had been a good Friday after all.

The fishing fleets were in port, so the crews were safe even if many of the vessels were tossed about like Matchbox toys and left heavily damaged or destroyed. The Alaska Railroad north of Seward was a tangled mess, and the railroad’s dock facilities and yards were in ruins. Preliminary reports by Governor William Egan’s office—he himself was from Valdez—estimated total damages of $205 million. In the light of late-twentieth-century hurricane disasters, this figure may seem small, but in 1964 it was roughly twice the state’s annual budget and equivalent to $1.14 billion in 2000 dollars. Final figures would more than double the early estimate.

Clearly, a new state still struggling to get its economic house in order could not begin to absorb such a staggering financial loss. Thus, amid such death and destruction, there was a silver lining. The U.S. military in Alaska was among the first to respond, helping others as well as its own. Alaska’s U.S. senators, E. L. Bartlett and Ernest Gruening, were in Washington, D.C., when the earthquake struck, but President Lyndon Johnson quickly dispatched a presidential jet to whisk them back to Anchorage along with Edward McDermott, the director of emergency planning. In the weeks ahead, Bartlett and Gruening led the efforts to secure major federal relief for Alaska. Bartlett drafted an emergency relief bill, and Gruening told the senate, “[The] State of Alaska has suffered a catastrophe which, in my reasoned judgment, surpasses in magnitude that suffered by any state of the Union in our Nation’s entire history.”80

Eventually, the federal government provided Alaska and its citizens aid totaling $393 million, of which $66 million was in low-interest loans that were later repaid.81 Even Ernest Gruening and others used to railing against the federal government’s neglect of Alaska were forced to admit that Washington had come through in a big way to help the state. In retrospect, the emergency aid measures were probably the only issue affecting Alaska ever to come before the U.S. Congress that was not the subject of heated debate. Future governor Jay Hammond, then a member of the state legislature, summed up the end result by noting in retrospect that “thanks to a benevolent federal government and the ensuing rebuilding boom, the earthquake ultimately proved to be an economic boon to many Alaskans.”82

And what of the land itself? Once again, it had demonstrated its dynamic nature. In the years ahead it would once again prove its resilience—up to a point. Salmon spawning beds that were covered with silt recovered, forests that were leveled sprouted new trees, and wetlands briefly inundated with salt water once again became critical bird nesting grounds. But reminders remain about the power of the land.

At the far eastern end of Turnagain Arm, easily visible from the highway between Anchorage and Seward, there is a forest of dead trees. They stand in stark contrast to the fiery hues of the fireweed that carpets the ground. Once there was a town here called Portage. Sure, it was never more than a little railroad town where the Alaska Railroad’s lines split to run south to Seward and east through the mountains to Whittier, but it was a town, a living, breathing, kid-hollering, dust-kicking town. The Good Friday Earthquake caused this entire area to sink, and in the process the town of Portage was flooded and destroyed. Unlike Seward, Valdez, and Kodiak, it was never rebuilt. The trees died when the freshwater table dropped and their roots could reach only salt water. Their skeletons remain as proof that the land does not stand still.