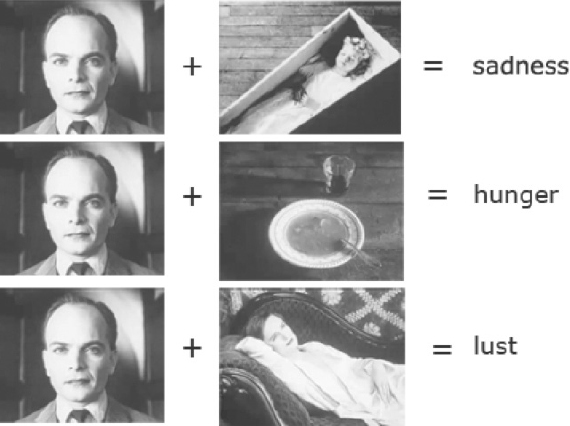

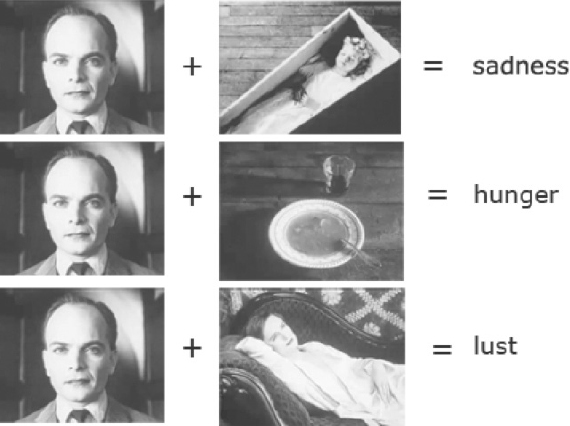

Lev Kuleshov, the Russian director, made his first film at the astonishingly young age of nineteen, and later successfully picked his way through the political minefield of Stalinist Russia to become a powerful figure in the Soviet film industry. He also made an astonishing psychological discovery (see Figure 22). He intercut shots of Ivan Mozzhukhin, a Russian silent film star, with three images: a dead child in an open coffin, a bowl of soup, and a glamorous young woman reclining on a divan. The audience were impressed by Mozzhukhin’s subtle acting, in turn indicating grief, hunger and lust. But Mozzhukhin’s acting was not so much subtle, as non-existent – the very same shots were used in each case; the juxtaposition of a relatively impassive face with scenes laden with emotion causes the audience to impose their own interpretations of Mozzhukhin’s emotional state.2

Figure 22. The Kuleshov effect. The interpretation of an ambiguous facial expression is changed dramatically when intercut with different scenes.1

The Kuleshov effect has been hugely influential in cinema – indeed, Alfred Hitchcock picks out the effect as one of the most powerful cinematic techniques in a TV interview in 1966.3 And this type of effect is not limited to intercutting film and juxtaposing distinct images. The background of a still photograph can dramatically change how we emotionally ‘read’ a face (see Figure 23).

Figure 23. US Senator Jim Webb at a campaign rally. With the context stripped away, he looks angry and frustrated; in the context of a campaign rally, he looks happy and even triumphant.4

We think that we are ‘seeing’ emotions in the face, and the face alone – but context turns out to be far more important than we imagine. The power of context is certainly a ubiquitous feature of perception. Consider, for example, the patterns in Figure 24, where an isolated portion of an image which, when considered alone, can be open to more than one interpretation (just like Mozzhukhin’s apparently subtle acting, or Webb’s excited facial expression in Figure 23), is disambiguated by looking at the wider context. There is a general principle at work here – the brain interprets each piece of the perceptual input (each face, object, symbol, or whatever it may be) to make as much sense as possible in the light of the wider context.

Figure 24. (a) A field of rabbits makes an ambiguous duck-rabbit look like a rabbit; (b) a field of birds makes an ambiguous duck-rabbit look like a bird; (c) the same phenomenon illustrated with numbers and letters.5

Could the Kuleshov effect apply not just to when we ascribe emotions of others, but also to how we ascribe emotions to ourselves? In a narrow sense, this seems all too plausible. Imagine the actor Mozzhukhin being presented with the images of himself, juxtaposed with images of tragedy, food or seduction, as we saw in Figure 22. He would surely be all too likely to read his own (static) expression just as we do – gently and subtly hinting at sadness, hunger or lust. One can imagine him inwardly congratulating himself on his marvellously understated acting, of course. But one could equally imagine that, if he thought that the photos had been taken at significant moments in his own life (rather than onscreen), Mozzhukhin would read his own expression just as we would: as signifying whatever emotion made the most sense in the context.

Imagine, now, a variation of the Kuleshov effect of the following, apparently rather peculiar, form: instead of (or perhaps as well as) seeing Mozzhukhin’s facial expression, we hear his heart-rate. Perhaps, with the appearance of the image (the coffin, bowl of soup, or young woman), we hear his heart-rate distinctly increase. How do we interpret this physiological signal? Just as before, I suspect it could be seen, variously, as a sign of an overwhelming despair, a sudden pang of hunger, or a surge of lust. And suppose we could hear his breathing become shallower and more rapid, and his adrenaline levels rising too: these indications would simply add colour to the same interpretation (and these signals will tend to vary in unison, of course).

Now consider how we interpret our own emotions, not in retrospect, but as they happen. We don’t normally have access to our facial expressions, of course, but we do know something about our own physiological state – we can, to a degree, feel our heart racing, our breath shortening, the tingle of adrenaline racing through our arteries. These signals are, of course, highly ambiguous, just like Mozzhukhin’s sphinx-like expression – they can indicate surges of feeling of many different kinds.

So perhaps we are inevitably subject to a kind of Kuleshov effect when making sense of our own emotions. Might the feeling of possessing one definitive emotion rather than another not be embodied in, or determined by, our bodily state, any more than our emotions are inscribed in our facial expressions? Indeed, isn’t our bodily state just another set of highly ambiguous clues that need to be interpreted, which can be explained in many different ways depending on the situation we are in? Perhaps, in short, emotions – including our own emotions – are just fiction too.

In 1962, a remarkable, and justly famous, experiment at the University of Minnesota provided some of the first direct evidence that this is right. Psychologists Stanley Schachter and Jerome Singer injected volunteer participants with either adrenaline or a placebo, and led them to a waiting area where they could sit for a while before the beginning of the experiment. They found that they had to share the waiting room with another participant who, so it seemed, was also waiting to be taken through to start the experimental session.

But the waiting room was the experiment – and the other person wasn’t a fellow participant at all, but a ‘stooge’ of the experimenters. The stooge acted either slightly manically (making and flying paper aeroplanes) or angrily (outraged by a questionnaire they had to fill in while waiting). The artificially adrenalinized participants had stronger emotional reactions to both stooges than those who had just received a placebo. Crucially, and remarkably, their emotional reactions were stronger in opposite directions. Confronted with the ‘manic’ stooge, participants interpreted their raised heart-rate, shortness of breath and flushed face as indicating their own euphoria; but with the ‘angry’ stooge, those very same symptoms were interpreted as signalling their own irritation.

Here we can see the Kuleshov effect in another guise – one which suggests that emotions of joy or anger do not well up from our inner depths. Instead, we seem to interpret our emotions in the moment: and we appear to do this based not just on the situation we are in (the person we are confronted with is behaving, say, manically or angrily) but also on our own physiological state (e.g. whether our heart is racing, our face flushed). So if a stooge behaves a little manically, and the experimental participant experiences a high level of arousal, then the participant is likely to interpret their positive feelings as strong positive feelings – after all, that would explain the raised heart-rate, shortness of breath, and so on. So they infer that they must be experiencing a state of perhaps mild euphoria. Confronted with the angry stooge, by contrast, suggesting feelings of annoyance in the experimental participant, the sheer strength of their physiological reaction (caused, of course, by the adrenaline) is interpreted as indicating a powerful emotional reaction. Participants perceive themselves to be very annoyed, rather than just mildly irritated.

Schachter and Singer’s experiment turns our intuitions about our own emotions on their head. We might imagine, for example, that emotions such as euphoria and anger have a distinctive physiological signal – a special state of the body, which gives them their special ‘feel’. If this were right, then we would expect a physiological change, such as that generated by an injection of adrenaline, to push us towards one of these supposed emotion-specific physiological states. So we might suspect that a shot of adrenaline will make us a little happier, wherever we start out, or perhaps a little crosser. Instead, the impact of adrenaline has opposite effects, depending on our interpretation of our situation. Roughly, adrenaline seems to signal to us that we must feel strongly about whatever emotional reactions seems natural – pushing a positive reaction towards mania, and a negative reaction towards outright anger. It seems that we are figuring out what emotion we must be experiencing, and doing so, in part, from the state of our own body. We tend to imagine that our emotions well up from within, and cause a physiological reaction (e.g. the fact that I am angry is making my heart race). But in reality it seems that we are figuring out what emotion we must be feeling, partly based on observing our own physiological state.

Wait a second, you may say. Isn’t all this talk of interpreting one’s own emotions a little premature? Perhaps a shot of adrenaline does have a simple emotional effect, after all: functioning as an intensifier. So perhaps the emotion wells up from within, as common sense might lead us to expect (based on how the stooge behaves – whether amusing or annoying). But then the strength of the experienced emotion is simply amplified (or suppressed) depending on a person’s level of arousal. Schachter and Singer have a clever twist in their experiment to look at this: among the people who got the adrenaline shots, some were told of the physiological effects they should expect (increased heart-rate, shortness of breath, etc.) and some were not (let’s call these the Informed and Uninformed participants).

We have already described the heightened emotional reactions of the Uninformed participants in Schachter and Singer’s experiment. But what about the Informed participants? If adrenaline merely acts as an emotional intensifier, then it should operate in just the same way whether we have been told about the likely effects of the shot or not. But if, instead, we are attempting to interpret our emotional experiences, in the moment, in the light of our physiological state, then our knowledge of the likely effect of the adrenaline shot should matter a lot. The Informed participants will attribute their state of high arousal to the shot; and therefore they will be less inclined to use it as a clue to the strength of that emotional reaction to the stooge (though, almost certainly, they won’t be able to ignore it entirely). And, indeed, this is exactly what Schachter and Singer found.

You might find all this disconcerting. Surely our emotions burst through from our mental depths. And mustn’t the emotions come first, and their physiological consequences second? Doesn’t our heart race because of the raging power of our feelings? That is certainly the common-sense story. But what if causation can also flow in the opposite direction: that is, our sense of inner tumult is, in part, caused by our perception that our heart is racing, our body tingling, our face flushed. It is our interpretation of the state of our own body that makes us interpret the very same jumbled thoughts as desperate, hopeful or quietly resigned.

This striking inversion of common sense is by no means new. It was foreshadowed by the American psychologist and philosopher William James – author of probably the most influential textbook in the history of psychology,6 and brother of celebrated novelist Henry James. James famously claimed that, when fleeing from a bear, we do not tremble because we are frightened, but rather, we experience the feeling of fear because we tremble. But of course, the physiological symptoms alone are not necessarily a signature of fear: we might experience the very same surges of adrenaline, raised heart rate, rapid breathing, at the starting blocks of a 100-metre race or before going on stage. Indeed, in many situations requiring concentration, effort or physical exertion, it can be difficult to tell whether we feel excited and ready to go, or nervous and fearful. When fleeing from a bear, though, few of us will interpret our physiological reactions as a thrill of excitement – the blood pumping wildly around the body and frantic breathing will unambiguously be perceived as indicators of terror.

With this in mind, I hope that Schachter and Singer’s experiment with adrenaline and emotions will now make perfect sense. Just like a hard-to-read face, an ambiguous duck/rabbit, or a  , your physiological state is highly ambiguous. The brain receives rather crude perceptual signals from your own body, indicating that your heart is pumping, and a certain amount of adrenaline is flowing, you are breathing rapidly, and so on – but what does it all mean? The experience of those perceptions of your own internal states depends, as ever, on the interpretation that seems to make sense, given the wider context. The very same physiological state can ‘feel’ like irritation (when you are with the angry stooge) and ‘feel’ like elation (when you are with the manic stooge), just as the very same facial expression in Kuleshov’s pioneering film-editing can be interpreted as grief, hunger or lust. Thus our feelings do not burst unbidden from within – they do not pre-exist at all. Instead, they are our brain’s best momentary interpretation of feedback about our current bodily state, in the light of the situation we are in. We ‘read’ our own bodily states to interpret our own emotions, in much the same way as we read the facial expressions of other people to interpret their emotions.

, your physiological state is highly ambiguous. The brain receives rather crude perceptual signals from your own body, indicating that your heart is pumping, and a certain amount of adrenaline is flowing, you are breathing rapidly, and so on – but what does it all mean? The experience of those perceptions of your own internal states depends, as ever, on the interpretation that seems to make sense, given the wider context. The very same physiological state can ‘feel’ like irritation (when you are with the angry stooge) and ‘feel’ like elation (when you are with the manic stooge), just as the very same facial expression in Kuleshov’s pioneering film-editing can be interpreted as grief, hunger or lust. Thus our feelings do not burst unbidden from within – they do not pre-exist at all. Instead, they are our brain’s best momentary interpretation of feedback about our current bodily state, in the light of the situation we are in. We ‘read’ our own bodily states to interpret our own emotions, in much the same way as we read the facial expressions of other people to interpret their emotions.

And, on reflection, it could hardly be otherwise. Consider, for example, a pang of envy – perhaps of a rival’s brilliant recent success or tales of her exotic holiday. The ‘pang’ is a physical feeling – but there can’t be a special kind of bodily feeling, perfectly specific to being envious of Edna’s coming top in the exam or perhaps being envious of Elsa’s trips to the temples and beaches of Vietnam. The difference between various experiences of envy is in the interpretation of a physiologically similar, and perhaps even identical ‘wave of feeling’, depending on what has just happened (e.g. whether I’ve just heard about Edna’s exam result, or caught a glimpse of Elsa’s holiday photos).

What Schachter and Singer showed is that we interpret the same physiological state not merely as different versions of the same emotion (e.g. being envious of different things) but as examples of different emotions entirely (anger versus elation). And this is perhaps surprising because it suggests that our ‘read-out’ of our physiological state – that is, the bodily basis of our feelings – really is surprisingly sparse.

Psychologists and neuroscientists who study emotion differ on just how sparse those physiological signals are. According to the influential ‘affective circumplex’ model of Boston College psychologist James A. Russell,7 for example, two physiological dimensions may suffice: one indicating level of arousal (this is the dimension that we have focused on so far), and the other indicating like-dislike. Russell calls this primitive monitoring of one’s own physiological state ‘core affect’. Our experience of having an emotion, though, involves an interpretation of ‘core affect’ based on our understanding of the situations we are in. So the ‘pang’ part of a pang of envy may be a mild kick of arousal (assuming the envy is not too extreme) and a nudge in the ‘dislike’ direction – but what makes me interpret this feeling as envy, rather than some other emotion, is the fact that these changes follow hearing about the exam results or spotting the holiday photos.

Our confusion about emotion has a long history. Plato has, as in so many things, helped shape our view of feelings and emotions for more than two thousand years. Sharply distinguishing thought and feeling, he conjured the metaphor that reason and emotion are like two horses pulling in opposite directions. But this viewpoint goes astray from the very outset – having an emotion at all is a paradigmatic act of interpretation, and hence of reasoning. We infer that we should interpret our bodily feelings as signalling anger, euphoria, envy or jealousy, based on the sparse signals from our physiology and social context. Just as we can see the face of another person as grief-stricken or lustful, angry or triumphant, just as we can see a  as a letter or a pair of numbers, just as we can see an ambiguous cartoon as a rabbit or a bird, we can feel the minimal signals from our body as anger or euphoria, mania or almost anything else, depending on our powers of interpretation – the very powers we use to make sense of other aspects of our lives and the world.

as a letter or a pair of numbers, just as we can see an ambiguous cartoon as a rabbit or a bird, we can feel the minimal signals from our body as anger or euphoria, mania or almost anything else, depending on our powers of interpretation – the very powers we use to make sense of other aspects of our lives and the world.

Now, of course, we sometimes imagine ourselves embodying Plato’s metaphor. Perhaps, we might conjecture, Elsa’s heart told her: Take that luxury tour of Vietnam, whereas her head said: Stop, you can’t afford it! And her heart, it seems, won the day. But the two forces tugging at Elsa were not emotion and reason, but two different types of reason. One set of reasons is based on the attractions of the holiday (and, one might churlishly speculate, the hope of exciting a little envy in others); another set of reasons is based on financial constraints (including fear of debt, worry over paying the bills). And each set of reasons is laden with feeling and emotions (desires, hopes, fears, worries). So the clash of ‘head’ and ‘heart’ is not a battle between reason and emotions; it is a battle between one set of reasons and emotions and another set of reasons and emotions.

But surely, you may object, I don’t interpret my own feelings – I just have them. Well, first of all, notice that this is not really an argument – just a reiteration of common sense. And notice, too, that we have already seen that other common-sense intuitions about how we think may be highly misleading. Recall the overwhelming intuition that I see the entire visual world in full colour and detail (the grand illusion) and that the visual world of my imagination (such as Chapter 4’s ‘mental cube’) is fully and coherently specified in 3D, rather than a mere shadowy and incoherent sketch. None the less, there seems something particularly shocking about the very suggestion that I have to interpret my own feelings.

Indeed, the ‘interpretative’ view of emotions has some particularly bizarre-sounding consequences, especially if we suppose that other aspects of one’s body, not just one’s level of arousal, could affect the interpretation of one’s emotional state. Suppose, for example, that I pretend to be happy: I force a cheery smile and a cheery dance. Isn’t the interpretative theory of emotions in danger of predicting that I infer that I must feel happy? And this can’t be right. Apart from its patent implausibility, this would imply a panacea for all human woes – just act as if everything is fine, and you’ll feel fine! And the possibility that such a panacea lies ready to hand, though strangely undiscovered or exploited for thousands of years of civilization, is surely remote indeed.

Yet perhaps taking up a ‘happy’ or ‘sad’ physical persona can affect your interpretation of your own emotions. Perhaps we can make our lives feel a little cheerier by acting a little cheerier. But push things too far and the effect may backfire: our emotion-interpreting system is highly sophisticated. We all know from personal experience how over-enthusiastic ‘emoting’ in other people can easily be interpreted as ironic or even mocking (and we’ve all experienced exuberant emoting which is disquietly ambiguous – is the other person genuinely delighted or cruelly disparaging?). So, if interpreting one’s own emotions works the same way, then when the ‘gap’ between one’s overt behaviour is too far out of line with the situation, then one’s own behaviour might itself seem ironic.

This could explain an intriguing study in which people were asked to move their heads up and down or from side to side (i.e. effectively asked to nod or shake their heads) while listening to unpersuasive or persuasive messages about whether students should carry ID at all times (the head-nodding was ‘justified’ as a test of the quality of the headphones they were wearing).8 People were, of course, more persuaded by the persuasive message; and, as by now you will be expecting, they were even more persuaded when nodding rather than shaking their heads as they listened to the message. The fact that they were instructed to nod didn’t entirely discount the normal ‘interpretation’ of nodding as a signal of agreement. But here is the twist: when the message was unpersuasive, the impact of head movements reversed – ‘nodders’ were actually less persuaded by the message than ‘shakers’. Yet from an interpretative standpoint, this makes sense. Suppose I see someone else nodding vigorously when given a patently unconvincing argument – this doesn’t look like agreement; it looks like mockery, a non-verbal ‘Yeah, right.’ And, if we are construing our own feelings from our actions, just as we interpret other people’s feelings from their actions, my own forced nodding in the context of something I obviously don’t think is convincing will be interpreted by me as ironic disdain, not honest agreement. And once I interpret my own nodding as ironic, I infer that I must think the message is really unconvincing.9

So, there is no panacea – living one’s daily life with a pencil between your teeth or otherwise maintaining a forced grin will not cause relentless cheerfulness or miraculously alleviate depression. And attempting to act cheerfully, when cheeriness is not what you are feeling, is all too likely to backfire – leading one to regard one’s actions as a hollow mockery of happiness, perhaps underlining one’s unhappiness even more thoroughly.

In the early 1970s, the University of British Columbia campus in Vancouver was the scene of a remarkable experiment on the origins of physical attraction and romantic feeling.10 Social psychologists Donald Dutton and Arthur Aron stationed attractive female experimenters at one end of a high, and slightly wobbly, pedestrian suspension bridge and also at the end of a second, solid, low bridge. Unsuspecting men were intercepted after crossing the bridge and asked to fill in a questionnaire; crucially, they were also handed the female experimenter’s phone number, supposedly in case they had any queries they would like to ask later. It turned out that the men felt far more attracted to the woman they met at the far end of the ‘scary’ bridge – and were far more likely to call their number.

Perhaps, in the light of the story so far, you may be able to guess why this happened? Walking across the high bridge, the fear of heights caused a surge of adrenaline in the male bridge-crossers. And the adrenaline was still washing around each unsuspecting male’s system when he met the attractive female experimenter. In the normal course of events, the extra adrenaline would probably be explained, reasonably enough, as a fear response – the bridge was conspicuously high and wobbly, after all. But now an alternative cause presented itself – the presence of the attractive female experimenter. Physical and/or romantic attraction is, undoubtedly, a possible cause of surges of adrenaline – so the men may naturally enough have interpreted their heightened physical state as generated by feelings of attraction to the young woman who was engaging them in conversation and asking them to fill in the questionnaire.

Far from knowing our own minds, we are endlessly struggling to make sense of our own experiences – and we can often jump to the wrong conclusions. Even attraction, it seems, does not well up from within from some primal source. We feel a surge of adrenaline as attraction rather than experiencing it as fear or anger, because of the circumstances that confront us – our brains are, moment by moment, attempting to interpret the minimal physiological feedback from our body. And, as Dutton and Aron showed, our inner interpreter can easily be fooled.

What, then, are the implications for romantic love? One slightly alarming possibility is that the very intensity of becoming close to a new potential partner causes high levels of arousal (and, possibly, high surges of positive feelings), which may be interpreted not as by-products of any new romantic encounter but as signalling the existence of a special ‘bond’, or as indicating particularly wonderful characteristics in the ‘other’. These signals are not necessarily misleading, of course – intensity of feeling may, to some degree, reflect the strength of the ‘connection’ between two people, for example. But the more or less precipitous collapse of many early-stage infatuations – a staple of gossip, psychotherapy and fiction – strongly suggests that the ‘signals’ are much less reliable than we think. We are, as ever, attempting to explain our feelings (and the other’s feelings), based on fairly sparse clues – and we are all too liable to err.

What is the ‘truth’ about love anyway? If we are in the grip of the illusion of mental depths, we are likely to be seduced by the idea that one’s feelings of love for a partner (or hoped-for partner) arise from ‘deep inside’. And, similarly, that hidden deep inside the mind of the other are feelings of love for oneself (or not, one may fear). But these inner ‘feelings’ are presumed to be mysterious, occult states, about which there is inevitably uncertainty and hand-wringing. So, for example, we are able to agonize endlessly, and without result, about whether and how much our beloved loves us; and, equally fruitlessly, about whether and how much we, deep down, really love him or her.

Yet, by now, we should at least treat with suspicion the idea that there is any mysterious inner state, buried deep in our lover’s or our own mind, that answers such questions once and for all. As we have seen, far more prosaic questions about our supposed ‘inner mental landscape’ turn out not to have clear answers: questions about the lighting, shadows or even the size of the ‘imagined cube’ and the perceived colour or detail of one’s current perceptual experience of objects viewed in peripheral vision.

Our emotions are no more real: they are creative acts, not discoveries from our inner world. So when we interpret a momentary flicker of expression across the beloved’s countenance, we can’t ‘see’ feelings of love, regret or disappointment. Rather, as victims of the Kuleshov effect, our brains will interpret an often highly ambiguous facial expression (together with any amount of background information, such as our suspicions, fears and hopes) as embodying perhaps tenderness, distraction, traces of boredom, or any number of other possibilities. And our interpretation of our own physical state as embodying our own ‘feelings’ for the beloved is also the result of our whirring brain actively explaining our racing pulse and shortness of breath as, in one moment, exhilarating signs of love, and at the next moment, as indicating that we are on the edge of despair.

Indeed, the parallel between emotion and imagery is exact. Just as we believe ourselves to be inspecting an inner mental ‘cube’ to find its shadows, so we believe ourselves to be looking deep within our innermost mental recesses to decide who we love and how much. But in each case, we are subject to an illusion – we are inventing answers to each question we ask ourselves as fast (or almost as fast) as we can ask them. So, in both cases, we have the sense that these answers are waiting, ready at our fingertips; and they are – but only because we are able to make them up, with wonderful fluidity, as we go along.

The belief that emotion is an inner revelation, rather than a creation of the moment, is, I think, not only widespread, but potentially dangerous. The illusion that words and actions generated in the heat of the moment, when our interpretations of our lives and of others are likely to be at their most incoherent, burst out from our inner core, can lead us vastly to overrate their importance. For centuries, an ill-judged intemperate word or action could, in many social circles, lead inexorably to a dual or feud; friendships and marriages can be horribly marred by the supposedly ‘telling remark’ or ‘revealing action’ that is presumed to be not a moment of momentary confusion, but an insight into the bitter truth. To believe that our capricious and inventive minds are pouring out hidden truths at moments of crisis can also lead the religious to doubt their faith, the brave to suspect their own cowardice, and the good to undermine their own motives.

The philosopher, logician and political activist Bertrand Russell writes memorably of a moment of apparent emotional insight in the autumn of 1901: ‘I went out bicycling one afternoon, and suddenly, as I was riding along a country road, I realized that I no longer loved Alys. I had had no idea until this moment that my love for her was even lessening. The problem presented by this discovery was very grave.’11 For Russell, this thought was no mere creation of the moment (perhaps a product of a frustrating morning’s work, or the aftermath of argument); instead, he interpreted it as an indisputable revelation, breaking through from a hidden subterranean emotional world. This proved to be a disastrous interpretation, at least for their relationship, which foundered rapidly, though not leading to divorce until twenty years later. Of course, the marriage might have failed in any case, but once Russell had received, as he saw it, a damning and final verdict from the ‘inner oracle’, he became utterly convinced that the relationship was dead. And with that belief firmly established in his mind, there was probably little hope.

Giving excessive weight to one’s transitory emotional interpretations is hardly the preserve of great philosophers. We all face a continual struggle to regard our thoughts and emotions as transitory creations, mere commentaries on the moment, rather than as bearers of undeniable truth. The danger is that one moment’s speculative thought (‘I don’t love Alys’, ‘I’m a hopeless failure’, ‘the world is terrifying’) becomes the next moment’s incontrovertible proof – the very thought is taken as its own justification. Indeed, the problem is so widespread, and can be so injurious, that an entire approach to mental well-being, so-called ‘mindfulness’ therapy, is primarily focused on breaking this illusion: seeing our thoughts and feelings, including, most importantly, destructive thoughts and feelings associated with depression and anxiety, as momentary inventions that we can step away from, criticize, or choose to dismiss. Needless to say, disrupting damaging patterns of thought is not easy – techniques involve achieving a sense of distance from one’s emotions by controlling (e.g. via breathing exercises) and paying close attention to one’s physiological state (e.g. heart-rate, levels of adrenaline). But as with Russell’s marriage, dealing with negative patterns of thought becomes so much more difficult if we are in the grip of the illusion of mental depth – if we see our emotions as infallible messengers from our inner world, rather than as products of flimsy and incoherent interpretations of the moment.

The potential for disastrous misunderstandings of emotions is even greater if we are entranced by the Freudian tradition that our words and actions can reveal inner mental truths in a highly cryptic form, which can none the less be mysteriously deciphered by the enthusiastic amateur or the ‘trained analyst’. And any resistance to the proposed ‘reading’, such as we saw with ‘Little Hans’, can, of course, be conveniently explained as defensiveness – and even interpreted as confirmation that the reading is correct. But, as we have seen, the entire project of attempting to fathom the emotions, motives and beliefs driving a person’s behaviour is doomed from the outset. The problem is not that it is difficult to fathom our mental depths, but that there are no mental depths to fathom.

So does this mean that love is an illusion? That the romantically entangled can do no more than spin fairy stories about each other’s thoughts and feelings, and their own? Not at all! The psychology of perception and emotion suggests that we should look for the truth about love not by attempting an impossible journey into our innermost selves, but by focusing instead on our patterns of thought and interaction in the here and now. Feeling fond of the other, helping and being helped in return, sharing revelations, surges of adrenaline and positive feeling at judicious and appropriate moments, sticking with each other through thick and thin – these aren’t just evidence of a deep, authentic inner state – the state, perhaps, of ‘true love’. They are the essence of what love is.

In an ever more mechanized world, and with science revealing the hidden processes of nature with ever more precision, the desire to reassert the value of the non-mechanical, the spiritual and the emotional can seem increasingly urgent. We humans struggle to find meaning in a world apparently governed by the iron laws of Newton’s (or Einstein’s) physics – even if those laws are leavened with a sprinkling of utter randomness from quantum mechanics.

Puzzling over the meaning of life is a particularly pressing and personal instance of puzzles about the meaning of things more broadly. Why does the word dog mean (very crudely) ‘furry, carnivorous, domesticated, middle-sized animal, which barks and is commonly a pet’; why do double yellow lines mean ‘no parking’ on British roads; why does a dollar bill, a pound coin, or a 20-euro banknote have a monetary value (rather than being mere objects that can be weighed, thrown, burned or melted)? In these cases, it seems natural to assume that meaning comes, in some roundabout way, from patterns of relationships. The word dog has developed its meaning because of the way we use it – its role in the language, in our lives, in its connections to the world (e.g. the existence and nature of dogs), the way our perceptual systems classify the world, and much more. But it is clearly a hopeless strategy to look for the meaning of the word by closely scrutinizing the word itself. The same goes for money: the value of physical currency is a product of enormously intricate relationships between people. It is a remarkable mutual agreement, backed by individuals, shopkeepers, manufacturers and governments, to treat currency in lieu of goods and services; it is supported by a rich pattern of norms, laws, anti-counterfeiting strategies and trust in the economy. The last place to look for the meaning of money (at least after the demise of the gold sovereign) is ‘within’: it is not the paper or metal that has value – no matter how closely we examine the patterns on banknotes or the precise alloy from which the coins are minted. Words are not mere sounds; money is not just the paper it is written on.

And the same is surely true for the search for meaning in our own experiences and in our lives. Emotions, then, have their meaning, not through some elementary properties of ‘raw experience’, but through their role in our thoughts, our social interactions and our culture. To be ashamed, proud, angry or jealous is not to experience the welling up of some primitive feeling – we are ashamed of specific actions, proud of particular achievements, angry at individual people for concrete reasons, and so on. Of course, such feelings are associated with a bodily state (just as words have physical form, as acoustic waves or patterns of ink; and just as money is embodied in paper and metal), but the bodily state – the rushes of adrenaline, the pounding of the heart – should not be confused with the emotion itself.

The same pattern surely applies to the meaning of our lives more broadly. The meaning of pretty much anything comes from its place in a wider network of relationships, causes and effects – not from within. So wondering if you are in love, whether you really believe in God, or whether you find a sentimental pop song charming or mawkish, should be a prompt for you to consider how your thoughts and feelings fit together; how they link with your actions and the actions of other people; how they compare with situations you have experienced in the past, and more. Such questions are not answered by a futile attempt to carry out a microscopic analysis of one’s inner sensations, or still less one’s soul.

With hindsight, one might view feelings as inherently unstable, as being continually invented and reinvented, moment by moment. Looking for some inner mental bedrock, perhaps we should look not at what we feel, but what we do. But, as we will see in the next chapter, if our feelings help determine our choices, then our choices may be just as malleable and capricious as our emotional lives.