MUCH ADO ABOUT FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT

Of all the provisions of the NAFTA, chapter 11, covering investment, arguably became the most consequential. Yet it was not necessarily the most controversial – at least, not at first. Indeed, critics of the NAFTA generally seldom mention investment as a major source of weakness in the agreement. However, to those who have watched the postwar evolution of rules governing capital flows, seeing them suddenly embedded in a free trade agreement such as the NAFTA was a novelty, with important consequences for the future evolution of both investment rules and the NAFTA itself.

The NAFTA marked a turning point in the global evolution of foreign direct investment rules. It was the first instance in which developed economies (Canada and the United States) with substantial investment flows between them had subjected themselves to a powerful set of dispute settlement mechanisms, known as investor–state dispute settlement (ISDS). A by-product of the postwar evolution of international law, ISDS procedures were designed to install rules under which foreign private owners of investment capital could pursue legal means of compensation from the state in the event of expropriation or nationalization of that property by the state.

Yet, whereas the NAFTA was a significant innovation in investment arbitration, the NAFTA’s recently negotiated successor, the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement, has significantly curtailed the role of ISDS between the United States and Mexico while eliminating it entirely between Canada and the United States.

The origins of NAFTA chapter 11, its impact on the debate over global investment rules and ISDS’s evident demise in the newly negotiated USMCA are the subject of this chapter. The conclusion is that, whereas the United States once aggressively pursued strong investor protections in bilateral investment treaties (BITs) with numerous developing countries, the NAFTA experience shook the confidence of all three governments in the merits of ISDS. The NAFTA experience prompted a significant rethink of the role ISDS should play in the broader governance architecture around global capital flows. This rethink was well under way prior to the NAFTA’s renegotiation in 2017/18, for reasons that aligned with broader concerns about sovereignty, the regulatory power of the state and the role of multinational corporations in the evolution of the global economy. However, the Trump administration’s rationale also included a less well-founded set of arguments around the incentives the NAFTA’s investment rules had created for the outsourcing of jobs.

The postwar origins of chapter 11

BITs, BITs and more BITs

The origins of the investor–state dispute settlement mechanisms of the NAFTA are part of a much larger history of the institutionalization of international economic activity in the postwar period. The advent of investment rules, and their inclusion within the NAFTA’s architecture, were the product of decades of efforts to situate private international commercial activity within an international legal and political system dominated by relations between states. However, the NAFTA experience with investment as part of the evolution of rules to fill a gap in the practice of international law has, paradoxically, served to undermine the public perception of these very rules. Chapter 11 of the NAFTA has frequently been at the centre of a storm of controversy around these rules.

The fundamental problem being addressed with investment protection rules is that private capital doesn’t flow as readily as many would like from wealthy developed states, where it is abundant, towards relatively underdeveloped jurisdictions, in which capital is scarce.

Although there is some debate about how to fully maximize the benefits of FDI (see Graham 2000:3–7; Swenson 2005; Salacuse & Sullivan 2005), one of the historical challenges for developing states is actually getting FDI to flow in their direction at all. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development reports that, in 2007, FDI outflows from OECD countries reached a record US$1.82 trillion in value, with outflows from the United States alone amounting to US$333 billion (OECD 2008). However, the disparity in flows of FDI between rich and poor countries is as stark as ever. As reported by the OECD, there is a strong correlation between FDI outflows from rich countries and FDI inflows to poor countries. In 2007 developing countries matched the record growth in FDI outflows from the OECD by attracting record inflows amounting to US$471 billion. However, the BRIC countries (Brazil, Russia, India and China) accounted for 50 to 60 per cent of all developing country inflows (ibid.; Palmade & Anayiotas 2004). In 2014 OECD countries still accounted for 40 per cent of FDI inflows and 70 per cent of all outflows – in spite of serious economic crises among them (OECD 2016).

Table 5.1 Global flows and US, EU shares, 2015

2015 (millions of US dollars) |

|

Global outflows |

1,474,424 |

Global inflows |

1,762,155 |

High-income OECD outflows |

1,098,527 (74.5% of total) |

High-income OECD inflows |

698,064 (55.0% of total) |

US outflows |

316,549 |

EU-28 outflows |

487,150 |

US inflows |

379,894 |

EU-28 inflows |

439,457 |

US + EU-28 outflows |

803,699 (61% of global flows |

US + EU-28 inflows |

819,351 (54% of global flows) |

LDC outflows (–China) |

701,090 (47.6% of global total) |

LDC inflows (–China) |

335,121 (19.0% of global total) |

Note: LDC = least developed country.

Source: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, “UNCTADstat” database.

Not much has changed. Moreover, as depicted in data from UNCTAD in Table 5.1, removing the large flows into and out of China leaves the rest of the developing world attracting a paltry 19 per cent of all global inflows.

Moreover, if we take away the large flows into and out of China, investment flows into the developing world represent a paltry 19 per cent of all global inflows. Economic theory suggests that capital ought to naturally flow from regions in which capital is abundant (rich, industrialized, OECD countries), and therefore inexpensive, to those regions in which it is scarce (poor, developing countries), and therefore expensive. The reasons for this discrepancy are multifold but include things such as poor infrastructure, the lack of market proximity and access to a skilled labour force.

The individual and international law

The 1648 Treaty of Westphalia is broadly accepted as the starting point of the modern state system. Scholars have subsequently debated the dominance of the state within that system and the difficulty it’s had incorporating a range of non-state actors – such as firms – into its formal structure. This challenge has largely been mirrored in the development of international law (law between states) since the Second World War, and international trade law in particular (Salacuse 2007). Although the role of individuals as subjects of international law has grown considerably in the postwar period, thanks to the emergence of human rights law, the debate over the role of private commercial entities has been raging since at least the eighteenth century (see Blackstone 1765–70; Bentham 2000 [1789]; Janis 1984). Customary international law is based on the search for legal principles flowing from norms of state behaviour, some of which have then been codified into formal treaties (including the NAFTA). Yet, because customary law relies so heavily on historic interpretation of state practice, pinning those legal principles down has been the subject of considerable debate (Goldsmith & Posner 2005; Koh 1997). In 1900 the Paquete Habana case was among the first to engage in a lengthy historical recitation of state practice regarding the seizure of private foreign vessels (US Supreme Court, Paquete Habana, 175 US 677 (1900); see Goldsmith & Posner 2005: 66–78). In addition to trying to define traditional state practice, Paquete Habana also tackled the problem of the role of individuals (the owners of the Paquete Habana) within customary international law. In the postwar period, but particularly since the 1970s, the rise of international human rights law has firmly entrenched individuals as subjects in international law, particularly as states have increasingly try to assert themselves on behalf of the individual (Koh 1997: 2614, 2624–9; Goldsmith & Posner 2005: 107–34).1 Nevertheless, the role of private and individual interests in international law and international relations remains controversial (Koh 1997: 2603–34; Wedgwood 1999; Rivkin & Casey 2000) and, surprisingly, unsettled.2

Non-state actors in international commerce

A similar pattern has developed in the area of private international finance. One of the central issues plaguing international commercial relations is that the private interests at the heart of international flows of goods, services and capital have traditionally lacked any “personality” within customary international law. Without standing or “personality” in the context of international law, private foreign commercial interests, like individuals, have had few avenues through which to pursue their international legal claims (Reif 2004; Salacuse 1990; Graham 2000: 20–4). In the case of foreign direct investment, this typically meant seeking compensation for expropriation through host-country court systems with no guarantee of national treatment. In the event of nationalization or expropriation of private property, private foreign commercial interests had little recourse. They could pursue their claims through the domestic legal systems of host countries, but the act of expropriation made this moot. Private entities could also petition their home governments to “espouse” their case diplomatically; in essence, take up their cause. Even when international agreements were part of the governing structure of commercial activity, provisions often required exhaustion of host-country legal avenues and then “espousal” before third-party legal process could be invoked (Vandevelde 2005).

The challenge within international commercial law has been to develop institutions and practices to deal with essentially private and commercial law issues in an international context dominated by the customary practice between states. Without international “personality”, private investors and exporters have had difficulties binding themselves contractually to sovereign hosts in ways that secure their market access or private investments, as would be the case in their home markets. Property rights regimes in most countries permit the use of “eminent domain” by the state to seize private property, most often for a public purpose such as a rail line, highway or other infrastructure project. The key is that, within a domestic setting, the private owners of that property have “standing” to challenge the state in court to ensure just compensation is paid for the proposed “takings”.

One popular mechanism for mitigating these problems internationally with respect to foreign direct investment has been the emergence and use of bilateral investment treaties (BITs) in the postwar era (Salacuse 1990: 664–73). The use of BITs between state parties to define the treatment of private investment, including rules for dispute settlement and compensation, have offered private interests a form of “personality” within international law through which they can defend their interests. Similarly, the provisions of chapter 11 of the NAFTA did on a regional basis what BITs have done for the international personality of private investors on a bilateral basis, by allowing disputes to be submitted to existing international arbitration bodies within the World Bank (ICSID) or United Nations (UNCITRAL) systems.3

The United States and BITs

Bilateral investment treaties have been a large part of the search for ways to fill the void in international law governing commercial activity and assist in the management of asymmetry between host sovereigns and the private holders of capital, frequently multinational corporations in developed countries such as the United States. For the United States in particular, these usually took the form of treaties of friendship, commerce and navigation (FCN), primarily covering trade in goods, but also the treatment of private property held by US nationals (Vandevelde 2005: 162). However, with the expansion of international capital flows following the First World War, the United States began expanding the use of these treaties to deal with the treatment of US nationals investing in foreign countries (Salacuse 1990: 656). After the Second World War innovation in FCNs included property protections for American firms (in addition to individuals) and required that host sovereigns consent to the arbitration of disputes through the International Court of Justice (ICJ) (Vandevelde 2005: 164–5).

Much like the United States, developed European states sought similar treaty-like arrangements to both facilitate and secure investment flows into parts of the developing world. Germany, in particular, spearheaded the European development of BITs, concluding the world’s first with Pakistan in 1959 (Salacuse 1990: 657). The United States did similarly, incorporating investment provisions within some 22 bilateral commercial treaties in the two decades prior to 1966 (Salacuse 1990: 656; Vandevelde 2005: 162).

In comparison with European countries, the United States was slow to adopt a formal BIT programme, doing so only in 1981. Moreover, by the end of 2014 the United States had negotiated and implemented just 41 BITs.4 One reason for the lower number of US BITs, apart from the programme’s short history, is that US-style BITs tended to be much more rigorous in spelling out the terms of the treaty, and they were more demanding of host-country investment protections than are those concluded by Europe (Salacuse 1990: 657; 2004). Nevertheless, in general, BITs have three basic objectives (investment protection, promotion and liberalization) within which there were eight basic content areas: (a) the scope of the agreement, (b) the conditions for the entry of FDI, (c) the general standards of treatment of foreign investment by host countries, (d) monetary transfers, or the repatriation of profits from host-country investments, (e) prohibitions on performance requirements, (f) protection from expropriation or nationalization, (g) compensation for losses from expropriation and (h) dispute settlement mechanisms (Salacuse & Sullivan 2005).

Each of these objectives has periodically been the focus of controversy, but once incorporated into the NAFTA the focus became just three of the above: (c) the general standard of treatment, or how the operation of foreign firms should be treated relative to incumbent domestic firms; (f) the definition of expropriation; and (h) the process by which disputes around expropriation should be settled.

Multilateral rules and bilateral problems

Numerous proposals for regional or multilateral investment rules or conventions, as well as schemes for investment security funds to guard against the nationalization or expropriation of private capital, have been hatched, among them the failed Havana Charter of 1948, which would have created the International Trade Organization (ITO), and the disastrous Multilateral Agreement on Investment in 1998 (Canner 1998; Dattu 2000; Kurtz 2002).

Among the most successful mechanisms to emerge from the struggle to find international investment rules was the creation of centres for the arbitration of disputes between consenting parties (states and private investors). In 1965 the International Centre for the Settlement of Investment Disputes was created as part of the World Bank, followed a year later by the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (Broches 1995: esp. chs 5–8). It was thought that the ICSID and UNCITRAL mechanisms would facilitate the satisfactory resolution of conflicts between foreign investors and sovereign hosts. However, up to 1970 few states had been willing to submit to the jurisdiction of these bodies, and the first ICSID arbitration case was not filed until 1972.

In fact, ICSID and UNCITRAL were created just prior to organized resistance to developed country dominance of global governance, as embodied by the Declaration of the New International Economic Order (NIEO), passed by the United Nations General Assembly in 1974 (Vandevelde 2005: 167). Among the provisions of the NIEO was the reassertion of the sovereign right to transfer ownership of assets to host-country nationals; in other words, expropriate foreign property and give it to domestic interests. ICSID and UNCITRAL have become important mechanisms for the resolution of investment disputes. But the use of their dispute resolution procedures requires the acquiescence of both parties to a dispute – something many nations are still reluctant to do.

In reaction to the NIEO movement, developed countries, particularly in Europe, responded through the pursuit of even more BITs (ibid.: 168–9). By the end of 2001 the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development had recorded nearly 2,902 BITs, the overwhelming majority of which continue to be concluded between developed and developing countries (UNCTAD 2014: 114).5 The dramatic rise in BIT activity since the Second World War (44 BITs in 2013 alone) has reflected the desire on the part of capital-exporting countries – and, more specifically, the private investors within them – to bring additional certainty to the process of investing in foreign countries with weak legal protections or a history of expropriation. For countries in need of development capital, particularly in the wake of the debt crisis of the 1980s, BITs have become an attractive way to solidify confidence in potential foreign investors regarding nationalization, expropriation, creeping confiscation through regulatory changes, or performance requirements such as local content rules (Swenson 2005).

Although the United States was slow adopt BITs relative to its European counterparts, the most consequential adoption of BITs in American commercial history was easily the trilateralization of the US Model BIT within chapter 11 of the NAFTA.

North American FDI asymmetries

On its face, North America would not be the first place where the introduction of a regime of aterritorial investment protection rules would need to be implemented. Indeed, the original BIT between Germany and Pakistan in 1959 is reflective of the overwhelming pattern of postwar investment protection agreements: dyads of developed and developing countries. According to UNCTAD, there are nearly 3,000 BITs and 350 treaties with investment provisions within them, the overwhelming majority of which are between dyads of developed and developing countries.6 This recurring pattern of dyads flows from concerns about comparatively weak property rights protections in developing countries and the lack of legal recourse to foreign holders of capital in the event of expropriation or nationalization by the host state.

In North America, the main source of comparable concern was Mexico, notably its nationalization of PEMEX in 1938. However, investment was also an irritant between Canada and the United States in the 1980s, as Ottawa implemented a series of nationalist energy policies favouring domestic over foreign (mostly US) investment in the energy sector (Mendes 1981; Glover 1974; Globerman 1984; Grover 1985). In the late 1980s and early 1990s Canada and Mexico were looking for new sources of foreign direct investment (Salinas de Gortari 2002: 37–47, 394–491; Hart 2002: 298–304).

Canada has historically managed its economy in the service of political unity behind a range of protectionist, sometimes nationalist, economic policies dating back to the late nineteenth century (Clarkson 2002: 207–8; Norrie, Orwam & Herbert Emery 2002; Norrie 1979; Phillips 1979; Dales 1979). However, the development of an extensive raw materials processing and manufacturing base has always necessitated access to significant pools of capital, of which Canada has few domestic sources. From Canada’s earliest years tariff structures were traditionally set to discourage the importation of value-added manufactures that would, in turn, encourage inflows of investment capital for plant construction to serve the Canadian market (Barnett 1976). These policies, aided by the rapid expansion of production capacity brought on by two world wars, helped Canada become one of the world’s premier industrial powers by the 1940s and 1950s.

Yet, into the 1960s and 1970s, many Canadians began to question the range of industrial policies that encouraged so much foreign investment in Canada. Concerns were raised in several quarters over the implications of foreign ownership of Canadian-based enterprises, and also because so much of Canada’s manufacturing sector was of a branch plant variety that conferred few spillovers into the broader economy (Clarkson 2002: 207–8). Indeed, by the late 1970s several economic studies suggested that subsidiaries of foreign-controlled firms (most of which were American) were spending very little on research and development (R&D) and that Canada ranked far behind other major OECD nations in R&D expenditures as a percentage of GDP (Fry 1983: 80). In the late 1960s the government of Pierre Trudeau began the push for what would later be referred to more colloquially as “the third option”. The third option itself intended to reduce Canada’s large and growing dependence on the US market for its economic prosperity, through trade policies directed at solidifying ties to other trading partners, notably Japan and the European Community. However, more generally, the 1970s were a period in which Canada adopted a series of policies supported by economic and political nationalists who worried about the influence of foreigners (namely Americans) on the Canadian economy. In addition to trade diversification, the Trudeau government, in 1980, campaigned on a platform that included the “Canadianization” of the economy, with a policy mix that included a more overt industrial policy, greater control in the energy sector and government review of incoming foreign investment (Hart, Dymond & Robertson 1994: 16; Fry 1983: 82).

Of particular concern to American (as well as many Canadian) business interests were policy changes to energy and investment embodied by the creation of the National Energy Program (NEP) and the Foreign Investment Review Agency (FIRA). According to Earl Fry, in 1980, when the NEP was created, foreign investors controlled nearly 70 per cent of all Canadian oil and gas production, and assets valued at over US$25 billion (Fry 1983; see also Globerman 1984). Supporters of the NEP argued that no other industrial country permitted such overwhelming foreign investor control over such key economic sectors. In several respects, the policy dilemmas the government of Pierre Trudeau faced were similar to those currently faced by many developing countries, and involved the apparent trade-off between attracting the FDI and spin-off technology transfer that were so important to Canada’s standard of living and exercising greater national control over the country’s own economic affairs. Through FIRA and the NEP, Canadian policy sent a chill wind of uncertainty through existing foreign-held operations and any future investment flows into Canada.

The stated goal of the NEP was to reduce foreign control of the oil and gas sector by 50 per cent within a decade. In theory, the NEP was not designed as a confiscatory programme to transfer foreign-owned assets to Canadian ownership but, rather, as an incentive programme for Canadian-owned operations. However, the differential in the incentives offered to Canadian firms in new and existing oil exploration put foreign-held operations at a significant disadvantage, weakening foreign-held asset values and paving the way for Canadian firms to acquire ownership stakes in them (Fry 1983: 86–7). American officials complained that Canadian policies were a form of “creeping expropriation” of private property. At a minimum, US officials charged that the NEP was a denial of national treatment and that the incentives offered to Canadian firms also had the effect of being equivalent to expropriation in instances when US-owned asset values fell, thereby facilitating their acquisition by Canadian interests. None of this involved the outright expropriation of American property, but the problems were similar in nature to those that US firms were encountering in developing countries – and the main reason for BITs.

In essence, the Canadian government changed the rules governing economic activity in the oil and gas sector starting in 1980. The changed rules affected asset values, which altered the choice set under which domestic and foreign firms exchanged property. The rule changes did not themselves make a new market for exchange, but they did dramatically alter the incentives for entry and exit from the Canadian market. Although the climate for foreign investment in Canadian oil and gas remained much more favourable than in other parts of the world, there were several prominent sales of American assets to Canadians as well as several instances of American firms simply leaving the Canadian market (ibid.).

Likewise, Canada’s Foreign Investment Review Agency, launched in 1974, also shifted the incentive structure facing potential foreign investors in many other sectors of the Canadian economy. FIRA’s mandate was to screen both new foreign investment and expansions of existing foreign-controlled firms within the Canadian economy. The purpose of FIRA was to ensure that foreign activities in Canada were of significant benefit to Canada, including considerations of employment effects, the potential for productivity enhancement, technological transfer to Canadians, the impact on competition domestically and the compatibility of provincial policies (ibid.: 89; Foreign Investment Review Act §3.1(1), 12 December 1973; Clarkson 2002: 204–10). Although FIRA approved virtually all investment proposals that it reviewed (Fry 1983: 89), the policy structure had the effect of also reshaping the institutions governing the acquisition and exchange of private property in Canada. In a sense, Canada’s nationalist economic policies were moving the goalposts. Lengthy and time-consuming application procedures, coupled with the absence of transparency in the review process and the arbitrary quality of many decisions, contributed to the addition of significant uncertainty regarding potential investments – a risk premium on foreign-controlled Canadian assets. The imposition, or threatened imposition, of “undertakings” by Ottawa on new investments – essentially, performance requirements as a condition of approval – constituted an additional set of constraints to the choice set facing foreign as well as domestic firms, many of which could then enjoy protection in the domestic economy afforded them by Canadian policies.

Canadian nationalists complained that the real impact of the NEP and FIRA was much less than promised by the rhetoric of the day. Yet foreign discontent over Canadian policies grew throughout the 1980s. In 1979 alone US$1.7 billion in FDI left Canada for the United States, while Canada took in only US$675 million. In 1981 capital outflows from Canada reached a record US$10 billion. In addition, the overall net outflow of capital from Canada, which averaged US$2 billion annually during the 1970s, jumped to US$10 billion during the early 1980s (ibid.: 101). In 1980 Canada’s share of all North American inward FDI was over 38 per cent; by 1985 that share had fallen to just over 23 per cent (Sancak & Rao 2000). On the other side, Canada’s share of all North American FDI outflows rose from just over 9 per cent in 1980 to over 15 per cent towards the end of the 1990s (ibid.) In short, Canada had become a less attractive investment climate for private capital (Hart, Dymond & Robertson 1994: 222).

The speed with which the United States had become a comparatively attractive destination for FDI was, in part, due to the policies of the US Reagan administration favouring deregulation and low taxes. Because of the policy divergence in Canada and the United States, as well as the growing competition for capital flows, in 1984 the Canadian government initiated a review of FIRA’s mandate that resulted in a name change, to Investment Canada, and a dramatic reversal of its function, from one of screening FDI to one of promoting Canada as a destination for FDI (ibid.). Much the same happened with the NEP, which was abandoned in 1984.

These specific Canadian policy reforms were part of a much broader opening of the Canadian economy brought about in the early years of Brian Mulroney’s tenure as Canada’s new prime minister (from 1984 to 1993), which included a 1985 proposal for a free trade agreement with the United States. US interest in such an agreement was driven, in part, by a desire to deal with specific Canadian policies, such as investment, that were hindering American interests and contributing to a generalized perception of Canada as hostile to foreign, and particularly American, capital (ibid.; Robert & Wetter 1999: 391). As an important exporter of capital itself, Canada had the interests of its own multinational corporations in mind in the pursuit of stronger investment provisions on a bilateral, regional and multilateral basis (Clarkson 2002: 219–20). The Canada–US Free Trade Agreement (CUFTA) dealt directly with investment issues, and in many ways reversed the just-described domestic institutional changes to property rights in Canada by internationalizing them in a formal agreement. By itself, chapter 16 of the CUFTA was essentially a BIT, complete with the three basic aims and eight content areas found in the US BIT model outlined above. The main difference (albeit an important one) was that it was one of the first such BIT-like agreements concluded between two developed countries.

Chapter 16 of the CUFTA guaranteed that investments made in the host country by each other’s nationals would be accorded treatment no less favourable than that accorded to firms in the domestic market (national treatment). Such treatment included securing rights for the establishment, acquisition, sale and conduct of enterprises in each other’s territory (CUFTA, article 1602). In addition, the threat of the imposition of performance requirements, such as minimum export levels or local content rules, as a condition of investment, as proposed under FIRA, would no longer be permitted under the agreement (CUFTA, article 1603). And, of course, both parties agreed to a prohibition on measures that directly or indirectly nationalized or expropriated FDI of the other party in its territory, and would not impose any measures that would be tantamount to expropriation, such as those that depressed foreign asset prices under the NEP (CUFTA, article 1605).

Ambiguity in international law governing investment between the two countries allowed frictions to develop during the 1970s and early 1980s, when policy changes in Canada generated significant uncertainty regarding new investment. The rules of the game had changed the incentive structure governing the exchange of private property in Canada, and, with few options available to American firms disadvantaged by Canada’s policy changes, there was little that could be done other than have government representatives complain on their behalf to Canadian authorities (espousal).

Interestingly, CUFTA chapter 16 was an incremental, not fundamental, change to institutions governing the distribution of property in North America. There were irritations, particularly in oil and gas, but both Canada and the United States have strong domestic legal systems and well-established procedures covering private property. Many US and Canadian subsidiaries in each other’s countries have successfully used domestic legal systems to pursue their rights. As such, the real need for a BIT-like investment chapter within a free trade agreement could reasonably be questioned. Moreover, the relative stability of property protections between the two countries made it so that chapter 16 was among the least controversial aspects of the CUFTA when the text of the agreement and free trade with the United States became the singular issue in the 1988 Canadian federal election.

Mexico chomps at the BIT

Like Canada in the early 1980s, Mexico in the early 1990s was looking for additional sources of foreign investment. Indeed, the pursuit of new investment capital was a significant factor in the Mexican government’s decision in 1990 to pursue free trade with the United States (Salinas de Gortari 2002; Cameron & Tomlin 2000).

Importantly, Mexico’s access to international capital flows was especially challenging as the country struggled to emerge from the crushing debt crises, soaring interest rates and falling oil prices of the early 1980s. As part of Mexico’s effort to put its economic house in order, the administration of Miguel de la Madrid began a long process of domestic economic reforms in 1985 that included privatization, deregulation and the start of a broad shift away from years of industrial import substitution (Salinas de Gortari 2002: 394–491). This general trend in Mexican economic openness was broadened and deepened under the administration of Carlos Salinas de Gortari in his efforts to bring greater privatization to state enterprises and banks, liberalize prices and wages and stimulate additional trade and investment (Pastor Jr & Wise 1998: 41–4; Salinas de Gortari 2002: 9–36). These reforms not only began to reverse Mexico’s economic fortunes but also won the country formal membership in both the GATT, in 1986, and the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, in 1994. However, the improvement in Mexican economic performance that went along with the reforms contributed to the appreciation of the Mexican peso and a rising current account deficit (Salinas de Gortari 2002: 27). In fact, between 1987 and 1994, the year the NAFTA was implemented, Mexico watched its US$8.8 billion trade surplus evaporate into a deficit of US$18.5 billion (Pastor Jr & Wise 1998: 46). The lingering effects of the debt crisis resulted in Mexico’s leaders casting around for ways to finance its mounting current account deficit as well.

Part of the solution was the revision of Mexico’s investment statutes, which had – much like Canada – turned what was an inward-looking, defensive investment climate into one that was more open and favourable for development capital to flow into Mexico. In 1989, for example, Mexico revised its 1973 Act to Promote Mexican Investment and Regulate Foreign Investment, which, as the title suggests, aimed to promote domestic investment while discouraging foreign. In 1993 Mexico went even further, partly in anticipation of the conclusion of the NAFTA’s investment provisions, by replacing the 1973 law with the Foreign Investment Law, which substantially liberalized Mexico’s investment regime (Vargas 2001: ch. 1; Cameron & Tomlin 2000: 59). Most famously, in 1989 the Decree for Development and Operation of the Maquiladora Industry greatly enhanced Mexico’s export-driven production by allowing foreigners 100 per cent ownership and preferential customs treatment provided that all production was exported (Salinas de Gortari 2002: 37–47).

However, as President Salinas discovered when he travelled to Europe in early February 1990 to attend the World Economic Forum meetings in Davos, Switzerland, the competition for investment capital had become even more intense with the entry of many former Soviet republics as competitors for scarce resources. European finance was not interested in Mexico (Cameron & Tomlin 2000: 1–3, 62–3). During the late 1980s the United States and Mexico engaged in several discussions on economic issues, and – much like Canada prior to the CUFTA in 1987 – considered pursuing several sectoral trade and investment arrangements with the United States. In fact, in 1987 the two countries concluded the Framework Understanding on Trade and Investment, which set the agenda for such negotiations (ibid.: 59). However, following the cool reception Mexico received in Davos, Salinas wasted little time in proposing a comprehensive free trade deal with the United States, formally doing so in early February 1990 (Salinas de Gortari 2002: 48).

But why did Mexico need a comprehensive agreement with the United States that covered investment when it had already liberalized its rules governing investment? Many scholars immediately suggest that Mexico concluded it needed an agreement with the United States in order to bring credibility to the reforms it had already put in place; a kind of policy “lock-in” that would ensure Mexico would remain a stable, predictable destination for investment. Given Mexico’s historical record of economic instability and lax enforcement of the rule of law, and a history of expropriation of foreign property symbolized by the 1938 nationalization of the Mexican oil sector and the 1982 nationalization of the banking sector, it is easy to understand why some inside and outside Mexico wanted these policy changes locked in. Salinas himself suggests as much, writing that the flow of foreign investment did not increase with the speed or in the volume that Mexico required. Both domestic and foreign investors argued that the rules in Mexico changed with each administration: one nationalized, the next privatized. It was essential to provide internal stability, and convince investors that Mexico’s policies would have continuity and long-term validity and that they would not depend on the discretionary powers of the administration in office (Salinas de Gortari 2002: 42).

In the creation of NAFTA chapter 11, we see almost all the arguments and rationales for the US BIT programme at play. For the United States, its firms now had a legal framework and set of mechanisms governing their activities and limiting the actions of sovereign hosts. For the sovereign hosts of American investment, additional credibility in policy reform at the expense of some policy autonomy was thought to be a reasonable price to pay for additional flows of foreign investment capital (Swenson 2005). All this appeared to be business as usual for the US BIT programme.

Some surprises lay ahead.

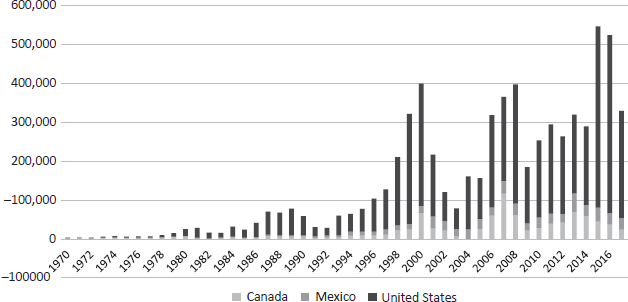

As the tables and graphs below depict, the impact of all these efforts is hard to discern. For example, as can be seen in Table 5.2, the United States accounted for 86 per cent of all inflows into North America in 1985. In 2016 that proportion was essentially unchanged. Some of the persistent gap can be correlated with the similarly persistent gap in GDP growth over the last 30 years (see Tables 5.2 and 5.3, and Figures 5.1 and 5.2), but the fact is that investment rules do not appear to have obviously redistributed the shares of investment capital flowing into each of the three countries.

The uneven results flowing from investment protection rules under the NAFTA were compounded by a broader collection on anxieties about sovereignty that began flowing from the operation of chapter 11 itself.

Table 5.2 North American FDI inflows (US$ millions)

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Table 5.3 North American FDI outflows ($US millions)

Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Table 5.4 North American gross domestic product (US$ billions)

Source: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Figure 5.1 North American GDP,1990–2017 (US$ trillions)

Source: World Bank, “World development indicators” database: https://databank. worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed 10 June 2019).

The NAFTA’s aftermath: something has changed

Members of Congress began to have doubts about chapter 11 just four years later, when Loewen Group, a Canadian firm, filed a chapter 11 case, claiming a 1996 Mississippi jury decision against Loewen Group denied the firm national treatment and effectively expropriated the firm’s private property and future earnings.7 Although this case was eventually dismissed in its entirety in June 2003, five years of litigation, the apparent mechanism provided by chapter 11 to circumvent domestic law, by undermining the decision of a Mississippi jury, suggested that the investor–state arbitration rules were not being used as intended. Never before had such rules been used by a firm from a developed country to challenge treatment of an investment in another developed country. As of mid-2018 there had been 55 chapter 11 cases alleging discriminatory treatment at the hands of a NAFTA government. Interestingly, only 17 of the 55 were filed against Mexico, the ostensible focus of chapter 11 protections in the first place; the rest were against the United States (17) and Canada (21). Between 1981 and 2012 not a single dispute against the United States had been launched under the US BIT programme.8 Yet, under the NAFTA, the majority of chapter 11 claims have been made against the two developed states with traditions of strong property rights protections.

Figure 5.2 North American foreign direct investment inflows, 1970–2017

Source: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, “UNCTADstat” database.

Critics have alleged that the application of national treatment within the NAFTA has conferred legal rights to foreign companies that are not accorded to domestic companies (Beachy & Wallach). What has really transpired is the application of an old legal regime (ISDS within BITs) to a new circumstance, in the form of substantial flows of investment between developed states. This new circumstance brought creative legal challenges as to the meaning and intent of the NAFTA’s language that had seldom been challenged when incorporated within traditional BIT dyads.

The NAFTA’s negotiators did not intend for chapter 11 to confer more legal rights to foreign investors than already afforded to domestic investors making investments “in like circumstances”.9 The agreement was mainly intended to fill a hole in international law and level the playing field between firms and host states. However, chapter 11 has generated a range of creative suits testing the definitional boundaries investment rules. Indeed, firms have alleged they’ve been denied a “minimum standard” or “fair and equitable standard” of treatment (article 1105) as required under customary international law (i.e. customary state practice).10 Others have claimed that the state has imposed forms of performance requirements (article 1106) on their investments as a condition of their investment.11 And, of course, the cases of many investors have claimed that the intervention of the state has been “tantamount to” expropriation (article 1110).12

Interestingly, virtually none of them allege that there was an outright nationalization or expropriation of property as we think about it historically, or as the NAFTA’s negotiators envisaged (Levy 1995).13 Instead, most allege discriminatory treatment in the application of regulatory measures that have the effect of expropriating (taking) private property.14

Few of these cases have resulted in arbitral awards,15 and most have been decided in favour of the state.16 However, by the late 1990s several public interest and environmental groups were growing increasingly concerned with the potential for the provisions of chapter 11 to be used to challenge state regulatory control over safety and the environment, in spite of explicit language within the agreement to the contrary (articles 1101 and 1114). Several cases became lightning rods for such criticism, as private investors tested the limits of the NAFTA’s rule governing private property rights. Cases such as Ethyl vs. Government of Canada, S. D. Myers vs Government of Canada and Metalclad vs. United Mexican States are all derided by environmentalists and others as a subversion of the state’s ability to regulate in the public interest.

The most watched of these cases, Methanex Corp. vs. United States, was a case in point. Methanex Corporation, a Canadian marketer and distributor of methanol, claimed damages of US$1 billion for alleged injuries resulting from a California ban on the use or sale of the gasoline additive MTBE that contains methanol as a key ingredient. Methanex contended that a Californian executive order and the regulations banning MTBE expropriated parts of its investments in the United States in violation of article 1110, denied it “fair and equitable” treatment in accordance with international law in violation of article 1105 and denied it national treatment in violation of article 1102.17

NAFTA, domestic law and where can you win?

In the absence of chapter 11, Methanex would have had little recourse but to pursue its claim through the US court system or via “espousal” of its claim through Canadian government diplomacy (Vandevelde 2005: 160; Egli 2006). The jurisprudence around takings in all three NAFTA countries is continuously evolving.18 Unfortunately, chapter 11 of the NAFTA did not attempt to harmonize those differences, and came up with no explicit definitions or criteria for determining which measures rise to the level of expropriation, no body of jurisprudence through which definitions have emerged and a clause in the agreement (article 1136 (1)) explicitly separating the cases from one another, thus limiting the scope for the creation of precedent.

Critics of the NAFTA worried chapter 11 would set standards for expropriation that were more liberal than those enshrined in the domestic law of all three countries, broadly shifting the balance within these proceedings away from a presumption of the pre-eminence of state prerogatives and towards private interests (Aldrich 1994: 609; Clodfelter 2001).19 If the NAFTA somehow established new legal grounds for property rights claims beyond their traditional conception, and the institutional mechanisms to pursue them, the implications for governing, including regulation in the public interest, could be profound (De Pencier 2000; Yee 2002). Private foreign actors would have recourse to a set of legal mechanisms and standards of expropriation unavailable to domestic firms (Yee 2002).

Two early chapter 11 cases, Pope & Talbot vs. Government of Canada and Metalclad vs. United Mexican States, offered some sense of where jurisprudence on chapter 11 was headed that explains the subsequent nervousness regarding the Methanex case (Alvarez-Jimenez 2006). The Pope & Talbot decision acknowledged that “the exercise of police power needed to be analyzed with special care”, and it also concluded that “regulations can indeed be exercised in a way that would constitute creeping expropriation”.20 Further, the tribunal argued “much creeping expropriation could be done by regulation, and a blanket exception for regulatory measures would create a gaping hole in international protections against expropriation”.21 Although the panel went on to reject Pope & Talbot’s claim because the regulatory change imposed upon it was not substantial enough, the decision inserted the notion of creeping expropriation due to regulatory changes squarely into chapter 11’s body of jurisprudence, thus placing the standards for expropriation under the NAFTA near those of US domestic law.

In Metalclad vs. United Mexican States, the chapter 11 tribunal went even further in expanding the definition of expropriation under article 1110, saying:

Expropriation under NAFTA includes not only open, deliberate and acknowledged takings of property, such as outright seizure of formal or obligatory transfer of title in favor of the host State, but also covert or incidental interference with the use of property which has the effect of depriving the owner, in whole or in significant part, of the use or reasonably-to-be-expected economic benefit of property even if not necessarily to the obvious benefit of the host State.22

By using the phrase “in whole or significant part” the Metalclad tribunal seemed to go one step beyond the “substantial” economic test put forward in Pope & Talbot and introduced a more expansive and subjective standard for expropriation, thus opening the door for a range of regulatory measures that even slightly infringed upon investment performance to be considered a form of expropriation, including the possibility of lost opportunity (see Fietta 2006). This definition went beyond standards for takings in any of the three NAFTA parties’ domestic legal systems, but was not out of step with where other investment arbitration bodies had also ruled (Aldrich 1994).

This line of reasoning around what constituted expropriation worried observers of the Methanex proceedings, in part because it would have the effect of extending to foreign firms a standard of protection from expropriation not available to domestic firms in any of the three NAFTA countries (Kirkman 2002; Yee 2002; Alvarez-Jimenez 2006). A legal victory for Methanex could have had profound impacts on the domestic legal systems had a separate, higher standard for expropriation been established (Yee 2002). Indeed, Methanex was also anxiously watched because it would have seemingly established chapter 11 as a parallel legal mechanism with a low threshold for challenging the state that was accessible only to foreign firms.

Governments to the rescue?

Outwardly, none of the NAFTA governments appeared nervous about Methanex. But they obviously were. In July 2001 the Free Trade Commission issued an “interpretation” of parts of chapter 11 (see United States Trade Representative 2001). The particular focus of the FTC’s interpretation was article 1105 and definitional ambiguities around “minimum standards of treatment”, “fair and equitable treatment” and “full protection and security” (Kirkman 2002: 389–90; Clodfelter 2001: 1278; Fietta 2006: 399). The FTC’s “interpretation” was arcane and lawyerly, but its timing came on the eve of Methanex’s notice of intent to file suit under chapter 11. Indeed, part of Methanex’s case took issue with the FTC’s apparent narrowing of the scope of “fair and equitable” (Kirkman 2002: 381–92; Alvarez-Jimenez 2006: 433).

The FTC’s interpretation language was subsequently incorporated into US negotiating positions in other free trade agreements, notably those with Chile, Singapore and five Central American states (Costa Rica, Honduras, Nicaragua, Guatemala and El Salvador) (Mann 2005). The investment chapters of each of these agreements went to great lengths, much further than the NAFTA, to more precisely define terms such as “fair and equitable” and “full protection and security” (Clodfelter 2001: 1278).23 The FTC did not come to a consensus on the definition of “expropriation” itself, but subsequent free trade agreements concluded by each of the three countries narrowed the scope of ISDS to be used as a vehicle for challenging the sovereign power to regulate in the public interest.24

1994: it was a very big year

The experience with investment protections under the NAFTA can readily be seen as an important watershed for the international debate over investment rules, the politics of the NAFTA itself and the fallout as manifested in the NAFTA’s successor, the US–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA). First, early chapter 11 jurisprudence alarmed all three NAFTA governments, prompting calls for significant reforms to the language, application and adjudication of investment rules, many of which were put into action in the mid-2010s. Second, until chapter 11 jurisprudence drew the attention of a broad cross-section of civil society in the mid-2000s, debates about investment rules were largely the purview of a small cadre of civil servants and investment lawyers. That all changed with the NAFTA, and chapter 11 became part of a much larger, mostly negative, narrative about the merits of the agreement. And, third, the debates about the NAFTA’s investment provisions inevitably fuelled some of the populist impulses around the agreement generally, and contributed to calls for an end to investment protections in North America and, ultimately, their strange, uneven reformation within the USMCA.

For most of the postwar period BITs generated virtually no controversy. According to the World Bank, Germany, the originator of the modern BIT in 1959, is now party to 160 BITs, France party to 111, the United Kingdom 117, nearly all with developing countries. In North America, Canada (23), Mexico (32) and the United States (58) are parties to 123 investment agreements.25 None of it generated dispute proceedings in which developed countries were defendants. This was partly due to the comparatively small amounts of capital flowing from developing countries into developed states upon which a dispute could be generated. With the rapid economic growth of several developing countries, notably China, those patterns have begun to change.

Figure 5.3 Arbitration cases under Energy Charter Treaty by year, 2001–2018

Source: Energy Charter Secretariat.

However, 1994 was important because of the BITs, complete with ISDS provisions, that were incorporated into trade agreements with application to other developed states: the NAFTA and the European Energy Charter (later expanded and renamed the Energy Charter Treaty).26 Much as Mexico was the assumed target of investment protections under the NAFTA, it was those with chequered histories of property rights protections – such as Russia or former Soviet republics – that were assumed to be the likely defendants in Energy Charter Treaty ISDS cases. Until the mid-2000s that’s how things unfolded. However, in recent years Energy Charter Treaty ISDS cases have spiked (Figure 5.3), and increasingly included measures in ostensibly developed countries with stable histories of property rights (Figure 5.4 and Table 5.5).

An ISDS earthquake and tsunami in Germany

North America and Europe have parallel experiences where investment dispute provisions within regional economic arrangements are concerned. In North America, it was Methanex. In Europe, it was Vattenfall. Both prompted reviews of government policy around ISDS, reform proposals and the near-total rejection of investment within the USMCA.

Table 5.5 International Energy Charter case distribution

Spain 32 Italy 7 Germany 2 Czech Republic 7 Poland 1 Slovakia 1 Russia 6 Ukraine 4 Romania 1 Hungary 5 Slovenia 1 Croatia 2 Bosnia and Herzegovina 2 |

Albania 3 Macedonia 1 Bulgaria 4 Romania 1 Moldova 2 Turkey 6 Georgia 1 Azerbaijan 2 Kazakhstan 5 Uzbekistan 1 Tajikistan 1 Kyrgyzstan 1 Mongolia 2 Total: 101 cases |

In 2009 the Swedish power company Vattenfall invoked the ISDS provisions of the Energy Charter Treaty, alleging Germany was unfairly and arbitrarily phasing out certain kinds of coal-fired power generation; generation Vattenfall had only recently invested in (Bernasconi-Osterwalder 2009). Yet, in 2012, Vattenfall set off alarm bells all over Europe when it again invoked Energy Charter Treaty provisions to challenge Germany’s decision to rapidly phase out all nuclear power generation in the wake of the Fukushima nuclear disaster (Bernasconi-Osterwalder & Brauch 2014). The political consequences of the Vattenfall cases could not have been worse, and nearly derailed the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) negotiations with Canada in 2016 (Khan 2016).

European civil society’s objections to the Canada–EU Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement included typically controversial issues, such as agriculture, intellectual property and culture, but ISDS became a lightning rod of controversy capable of drawing tens of thousands of protesters into the streets of European cities (Deutsche Welle 2016).

The controversy flowing from Vattenfall effectively hijacked the CETA, forcing both parties into a rapid rethink of their positions on ISDS (European Commission 2015a). For Europe, the CETA quickly became a high-stakes test bed for hastily cobbled-together ISDS reform proposals (ibid.; Puccio & Harte 2017). On the horizon was the proposed Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) negotiations with the Americans, the first such negotiations over investment since the failed Multilateral Agreement on Investment in 1998 (Graham 2000; Canner 1998).

In the United States, the Methanex case rattled nerves inside and outside government. In addition to prompting the Free Trade Commission’s “interpretation” of chapter 11 in July 2001 (Anderson 2017), the controversy also prompted the first US government review of its Model BIT since 1994, when that US Model BIT had been inserted into the NAFTA. When unveiled in 2004, the new US Model BIT included substantial changes aimed at stemming the most notable criticisms of the NAFTA’s investment rules. Among these changes was explicit language limiting the capacity of firms to challenge the state’s right to regulate in the public interest, together with clearer definitions of “expropriation” and “standards of treatment” firms could reasonably expect (Kantor 2004; Anderson 2017). The US Model BIT was slightly upgraded again in 2012, the language from which found its way into the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) (Anderson 2017: 2956–60). Although the Trump administration withdrew its support for the TPP, the changes to investment were enough to allay the reservations of other state parties about ISDS. Of note is Australia, which in mid-2011 was sued by the Hong-Kong-based subsidiary of American tobacco giant Philip Morris, under the terms of the 1993 Hong Kong–Australia BIT.27 Like Methanex under the NAFTA, Philip Morris alleged that an Australian public health measure (tobacco product labelling) violated the terms of the BIT (Easton 2015). In August 2011 the Australian government turned its angst over ISDS into policy by discontinuing the inclusion of ISDS provisions in future trade agreements (Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade 2011) – until ultimately agreeing to the inclusion of ISDS in the final TPP text of 2016.

In Europe, the two Vattenfall cases against Germany concentrated opposition to ISDS, imperilling the final stages of CETA negotiation with Canada (Whittington 2014). At the behest of Germany, the European Commission surveyed member state governments via the Council of the European Union (government ministers) in 2015 about whether ISDS should be a part of future European trade agreements at all (European Commission 2015a).

Much like the 2004 US Model BIT review, the European review generated new recommendations reasserting the state’s right to regulate in the public interest, promoting enhanced restrictions on the scope for private firms to claim expropriation and declaring the intention to establish a permanent “investment court” (Matic 2017; see also European Commission 2015b; 2015c). The eleventh-hour incorporation of European preferences in the CETA saved the agreement from near-certain rejection by member state parliaments.

Europe’s efforts vis-à-vis the CETA were about a much bigger negotiation: the proposed Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (Matic 2017; European Commission 2015b; 2015c). However, the debate on both sides of the Atlantic flowing from the NAFTA about investment governance firmly planted a range of possible reforms on the table: reform of the age-old BIT, as the United States had done; scrapping ISDS altogether, as the Australians did in 2011; or moving towards pooled institutionalization of investment through an “investment court” or other state-driven mechanism, as Canada and the European Union had done.28

Investment spaghetti

Chapter 3 of this volume noted how the proliferation of free trade areas since the end of the Cold War was creating an overlapping, inefficient set of commitments that seemed anachronistic in the context of a multilateral trading system predicated on non-discrimination. As chronicled by UNCTAD, the postwar period has seen the proliferation of investment treaties and trade agreements with investment rules embedded within – currently numbering over 3,000.

Figures 5.4(a) through 5.4(f) depict each of the investment treaty commitments of the NAFTA parties to each other and to non-NAFTA countries embedded in BITs or via investment rules in free trade agreements. Economists have not focused on the incentives created by investment treaties in the same way they have with respect to trade diversion and rules of origin associated with the trade in goods. However, investment treaties are inherently designed to incentivize capital flows that would not otherwise happen in the absence of their legal protections.

Investment treaties have evolved in a relatively standardized manner; the language found in the US Model BIT is not so different from that in Canada’s foreign investment promotion and protection agreements (FIPAs). However, as the NAFTA experience (as well as that with the Energy Charter Treaty) suggests, investment rules have generated incentives for both capital flows and legal action centred on the interpretation and meaning of those commitments. Of the more than 3,000 investment treaties around the world, North America accounts for fewer than 150. However, the potential for a spaghetti bowl of commitments would be obvious if Figures 5.4(a) through 5.4(f) were to be superimposed on one another.

If the proposed USMCA is ratified by all three governments, North America’s investment spaghetti bowl will become more convoluted still.

When the Trump administration initiated the renegotiation of the NAFTA in early 2017, investment was thought to be a major target for reform. Indeed, reform work undertaken on different tracks by Canada and the United States found its way into the investment provisions of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (chapter 9), to which all three NAFTA countries were parties until the Trump administration withdrew in January 2017. The investment chapter of the TPP contained many reformist nods to transparency, reassertions of the state’s right to regulate, clarity on expropriation and minimum standards of treatment, but also a basic commitment to investor–state dispute settlement. Importantly, the language of the TPP investment chapter, like NAFTA chapter 11 more than two decades earlier, was grafted primarily from the 2012 US Model BIT.

Judged by the Trump administration’s announced priorities, investment in the NAFTA renegotiation was mostly going to be about tinkering around the edges of the existing US Model BIT (United States Trade Representative 2017: 9). Indeed, the Trump administration’s announced position on investment aimed to affirm the United States’ long-standing efforts to prohibit expropriation, the imposition of performance requirements or limitations on capital transfer, or other provisions inconsistent with US domestic legal standards (ibid.: 8). Moreover, there were important post-NAFTA US BIT objectives around transparency, public access to dispute settlement (ISDS) hearings and third-party amicus submissions to those proceedings.

At the same time, the controversy swirling around chapter 11’s perceived threat to sovereignty, coupled with the Trump administration’s openly nationalist positions on economic policy, led some observers to conclude that significant changes to investment were possible. Moreover, Robert Lighthizer, the United States Trade Representative, had introduced a new critique of investment provisions that resonated with President Trump and his supporters: the NAFTA’s investment rules conferred a subsidy to American firms investing abroad, incentivizing the outsourcing of jobs to Mexico (Ikenson 2017).

When the draft text of the USMCA was released in the fall of 2018, investment turned out to be an area of surprisingly significant change. Surprising because investment was never the source of high-profile tension between the three countries the way rules of origin, wage rates or the Trump administration’s broader imposition of steel and aluminium tariffs had become. The punchline of the USMCA investment text is that, although firms’ so-called “legacy investments” (those made by firms while the NAFTA was in force) will still have access to ISDS under chapter 11 of the NAFTA (see USMCA article 14.2.4 and annex 14-C), Canada and the United States have eliminated ISDS altogether in the new USMCA. In other words, firms will no longer have access to ISDS for future investments in either country. There are still standard prohibitions against expropriation, standards of treatment and the imposition of performance requirements, but less clear is what mechanism would be invoked in the event of a breach of the USMCA’s revised rules. Moreover, the state-to-state consultative dispute settlement mechanism of chapter 31 specifically excludes investment from being handled there (USMCA article 31.2).

Figure 5.4(a) US FTAs with ISDS provisions

Figure 5.4(c) Canadian FTAs with ISDS provisions

Figure 5.4(d) Canadian BITS or FIPAs

Figure 5.4(e) Mexican FTAs with ISDS provisions

More puzzling still is that, under the new USMCA, ISDS will still apply between Mexico and the United States in a select group of sectors, mostly around potential breaches of government contracting in oil and gas, telecommunications, transportation and infrastructure (USMCA article 14.2.4 and annexes 14-D and 14-E.6).

Unfortunately, North America’s investment governance regime is quickly becoming a confusing patchwork, with the very kinds of uncertainties that discouraged flows of private capital and BITs were designed to simplify. Canada and Mexico remain members of the oddly renamed Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP-11), and thus subject to that agreement’s investment disciplines – including ISDS. The United States, on the other hand, currently sits outside the TPP, has eliminated the application of ISDS bilaterally with Canada and has an arrangement with Mexico for ISDS to apply in specific sectors.

At the time of writing the USMCA’s legislative ratification in all three countries was far from certain, particularly in the United States, where it seemed likely to fall off the 2019 legislative calendar and beyond as partisanship over the Trump presidency raged and the 2020 presidential election campaign neared. Moreover, significant changes, including to investment, could yet be imposed by the newly elected Democratic majority in the House of Representatives. There are critics of ISDS among Democrats and Republicans on Capitol Hill who will be happy with its elimination between Canada and the United States; indeed, there could be demands that it also be scrapped in the US–Mexican context as well. However, there will also be pressures from the US business community to restore ISDS fully to the USMCA, in the belief that ISDS gives American businesses operating abroad an important set of assurances in securing their investments. Indeed, American business interests were at the forefront of shaping the US BIT programme, and were integral to the reform efforts in the mid-2000s and affirming the role and utility of ISDS in the TPP just a few years ago.

As President Trump frequently notes, “We’ll see what happens …”

1. Jack Goldsmith and Eric Posner put forward a realist perspective on the emergence of human rights law rooted in self-interest and the coincidence of interests among states rather than the growing power of non-state actors and international regimes in the postwar era.

2. Although human rights law has developed rapidly over the past several decades, the debate over the proper status of individuals within international law continues with respect to US reservations to the International Criminal Court, as well as the uproar over “enemy combatants” in the “War on Terror” and whether they should be given the same protections as uniformed soldiers under international law. See US Supreme Court, Hamdan vs. Rumsfeld, Secretary of Defense, et al., certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia circuit, June 2006.

3. Respectively, the Convention on the Settlement of Investment Disputes between States and Nationals of Other States (ICSID) or the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL).

4. Department of State, Office of the Legal Adviser, “Claims and investment disputes”: www.state.gov/bureaus-offices/bureaus-and-offices-reporting-directly-to-the-secretary/office-of-the-legal-adviser/international-claims-and-investment-disputes (accessed 10 June 2019); Department of Commerce, Trade Compliance Centre, “Bilateral investment treaties”: http://tcc.export.gov/Trade_Agreements/Bilateral_Investment_Treaties/index.asp (accessed 21 July 2019).

5. In 2001 only 8 per cent of all BITs concluded were between developing countries, reflecting the relative lack of FDI flowing between them.

6. UNCTAD, “Investment Policy Hub”: http://investmentpolicyhub.unctad.org/IIA.

7. See the Loewen Group and Raymond L Loewen vs. United States of America, Statement of Claim, 30 October 1998.

8. In 2012 four separate cases were launched in connection with the Allen Sanford financial services Ponzi scheme fraud, one each using the investment protection provisions of, respectively, the US–Uruguay BIT, the US–Peru FTA, the US–Chile FTA and the CAFTA-DR.

9. See Free Trade Commission Clarifications Related to chapter 11, 31 July 2001.

10. ADF Group vs. United States, Methanex Corp. vs. United States, S. D. Meyers vs. Government of Canada, Waste Management vs. United Mexican States, Metalclad vs. United Mexican States.

11. ADF Group vs. United States, Ethyl Corp vs. Government of Canada, S. D. Meyers vs. Government of Canada, Metalclad vs. United Mexican States.

12. Methanex Corp. vs. United States, Ethyl Corp. vs. Government of Canada, S. D. Meyers vs. Government of Canada, Waste Management vs. United Mexican States, Metalclad vs. United Mexican States.

13. An exception here is AbitibiBowater Inc. vs. Government of Canada, launched in April 2009. Abitibi, a US forest products company, alleged that the province of Newfoundland and Labrador directly expropriated the firm’s assets via provincial legislation. In 2010 Ottawa settled with AbitibiBowater for C$130 million.

14. One possible exception to this is Metalclad vs. United Mexican States, in which Metalclad was forced to abandon an investment to operate a hazardous waste facility in Mexico. The divestiture of the facility resulted from a bureaucratic dispute between local and federal officials in Mexico over permits for operation that the tribunal ruled was tantamount to expropriation, but not outright expropriation. The tribunal awarded Metalclad US$16.7 million on 30 August 2000, only to have the award set aside by a British Columbia court.

15. Pope & Talbot Inc. vs. Government of Canada, S. D. Myers vs. Government of Canada, Ethyl Corp. vs. Government of Canada (settled outside arbitration), Metalclad vs. United Mexican States.

16. For example, ADF Group vs. United States, Loewen Group Inc. vs. United States, Mondev International Ltd vs. United States, Azinian et al. vs. United Mexican States, Marvin Roy Feldman Karper (CEMSA) vs. United Mexican States (partial dismissal); Methanex Corp. vs. United States.

17. See Methanex Corp. vs. United States, Notice of Claim, 3 December 1999.

18. Legal battles over the fifth amendment’s property protections and takings remain unsettled, with tests for regulatory takings emerging in the early twentieth century with Pennsylvania Coal Co. vs. Mahon, 260 U.S. 393 1922 introducing the concept of de facto, or regulatory, takings. However, Kelo vs. City of New London on 23 June 2005 and the reaction to it have generated new uncertainties about the state and takings; see The Economist (2006).

19. Formally named the Declaration of the Government of the Democratic and Popular Republic of Algeria Concerning the Settlement of Claims of the Government of the United States of America and the Government of the Islamic Republic of Iran (Claims Settlement Declaration), 19 January 1981.

20. See Interim Award by Arbitral Tribunal in the Matter of an Arbitration under Chapter Eleven of the North American Free Trade Agreement between Pope & Talbot and the Government of Canada, 26 June 2000, 35: www.dfaitmaeci.gc.ca/tna-nac/documents/pubdoc7.pdf.

21. Interim award, Pope & Talbot vs. Government of Canada, 34.

22. Award between Metalclad Corporation and the United Mexican States, ICSID Additional Facility, Case no. ARB(AF)/97/1, 30 August 2000: www.worldbank.org/icsid/cases/awards.htm.

23. See article 10.4 of the United States–Chile Free Trade Agreement, article 10.5 of the US–Central American FTA and article 15.5 of the US–Singapore FTA, all available at www.ustr.gov. Each of these agreements also contains a provision regarding the parties’ shared understanding regarding the definition of the “minimum standard of treatment” under customary international law, which says that “the customary international law minimum standard of treatment of aliens refers to all customary international law principles that protect the economic rights and interests of aliens”.

24. US–Chile FTA, annex 10-D, 4(b): “Except in rare circumstances, nondiscriminatory regulatory actions by a Party that are designed and applied to protect legitimate public welfare objectives, such as public health, safety, and the environment, do not constitute indirect expropriations.” See also US–Central American FTA, annex 10-B, and US–Chile FTA, annex 10-A. See also Inside U.S. Trade 2002a; 2002b.

25. See World Bank, International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes, “Database of bilateral investment treaties”: https://icsid.worldbank.org/en/Pages/resources/Bilateral-Investment-Treaties-Database.aspx.

26. See the Energy Charter Treaty, at https://energycharter.org/process/energy-charter-treaty-1994/energy-charter-treaty.

27. Technically, the Agreement between the Government of Hong Kong and the Government of Australia for the Protection of Investments, 15 September 1993.

28. See European Commission (2017). See also the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA), article 8.29; and Department of State (2004); (2009).