GLOBAL DOMINATION

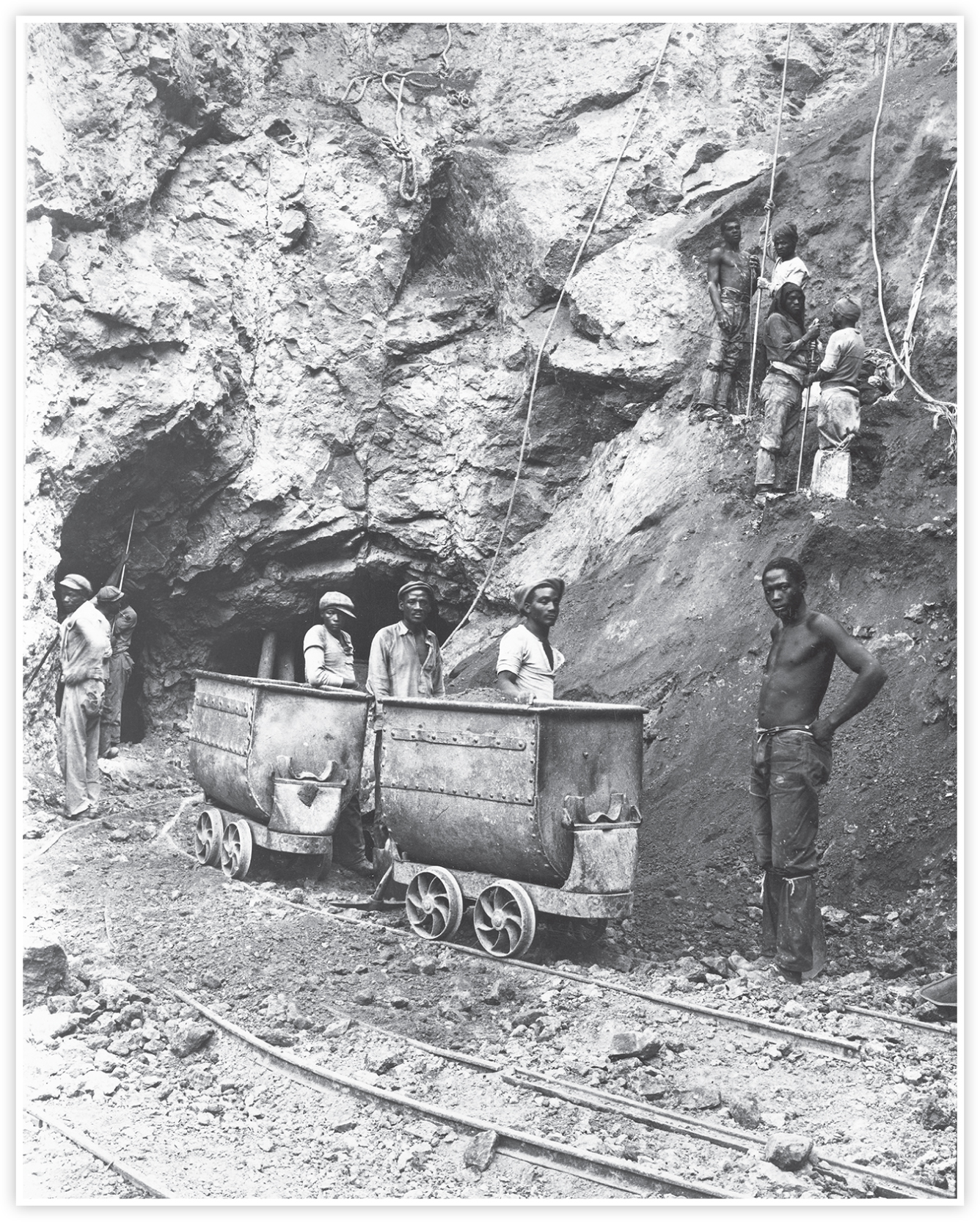

South African diamond mine, 1911. Source: Library of Congress.

Queen Victoria’s diamond jubilee, marking the sixtieth anniversary of her accession to the throne, was the symbolic climax of European imperialism. Suggested by Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain, the celebration on June 22, 1897, was a splendid “Festival of the British Empire,” attended by eleven prime ministers from the self-governing dominions. Barely visible in the flickering images of a film taken at the time, all of London was decked out with flags, garlands, and curious crowds, held back by soldiers in tall fur hats. Military units from all over the empire paraded on foot or on horseback through the city streets in colorful uniforms, including Canadians in red serge and Indian regiments in native garb. Led by the octogenarian queen in a horse-drawn carriage, the procession stopped in front of St. Paul’s Cathedral for an open-air service. Local celebrations in Britain and the colonies marked the day with speeches and fireworks. The diamond jubilee displayed the military might of the empire and the affection of its many subjects for their aging monarch.1

Contemporary propagandists and later commentators never tired of touting the benefits of empire for the colonizers as well as the colonized. Writers like H. Rider Haggard penned exciting stories such as the adventures of Allan Quartermain, which were set in Africa and became the model for the Indiana Jones movies. Journalists such as a young Winston Churchill vividly described rousing colonial victories against superior numbers of dervishes without any qualms about the ethics of their slaughter. A century later the jihadist chaos has once again drawn attention to some of the advantages of imperial order when compared to the disruption caused by clashes between religions or nation-states. British historian Niall Ferguson has argued therefore that “the Empire enhanced global welfare” as an early form of “Anglobalization” by spreading liberal capitalism, the English language, parliamentary democracy, and enlightenment in schools and universities. Pointing to the benign impact of empire, he concluded that “the imperial legacy has shaped the modern world so profoundly that we almost take it for granted.”2

Over the century mounting criticism, however, turned imperialism into one of the most hated terms in the political vocabulary. Novelists such as Joseph Conrad portrayed European exploitation and racism in compelling stories like his novella Heart of Darkness. Liberals such as John A. Hobson attacked colonialism for having “its sources in the selfish interests of certain industrial, financial and professional classes, seeking private advantages out of a policy of imperial expansion.” During World War I the revolutionary Vladimir I. Lenin claimed that “the economic quintessence of imperialism is monopoly capitalism” in order to argue that the chain of imperialist exploitation could be broken at its weakest link, his native Russia. Eager to have a theoretical justification for overthrowing European rule, many anticolonial intellectuals embraced this critique of exploitation in their national liberation struggles. Inspired by resentment of America’s Cold War support for Third World dictatorships, much postcolonial scholarship continues to excoriate the nefarious consequences of imperialist racism and white oppression.3

The intensity and longevity of the normative debate about imperialism underlines the centrality of empire in modern European history. For centuries, the quest for resource-rich overseas possessions dominated the politics of western states, while the eastern monarchies similarly sought to acquire adjacent territories. Much of the raw material used by Europe’s industries came from the colonies, while finished products were exported to the captive colonial markets. Many European attitudes reflected a sense of superiority over foreign “natives,” while precious objects of imperial culture graced the drawing rooms of the European elite. As a result of this unequal interaction, empire was omnipresent in the metropolitan countries. At the same time, non-Europeans encountered whites first in the guise of imperial explorers, traders, missionaries, officials, or officers. Their understanding of and feelings about Europeans were therefore profoundly shaped by their experiences with imperial control and economic exploitation.4 At the turn of the twentieth century imperialism characterized not only Europe’s domination over the world but also the world’s reaction to Europe.

Both as a cause and as a result, modernization was deeply involved in the imperial project, testifying to the ambivalence of its dynamism. On the one hand, European military superiority over indigenous peoples rested on the technological advances in weapons and organization that modernity offered. The restlessness that propelled exploration, the greed that motivated risk taking, the individualism that encouraged emigration, and the rule of law that made contracts enforceable were fundamentally modern. On the other hand, the imperial imprint on colonized societies was profound, spreading an exploitative form of modernization by force and persuasion around the entire globe. By creating plantations, trading houses, government offices, and military barracks as well as establishing schools, hospitals, and churches imperialists disrupted traditional patterns of life. While imperial possession reinforced the European sense of arrogance and confidence in progress, it imposed a perplexing mixture of oppression and amelioration on the colonized. It is therefore essential to recognize the deeply problematic connection between empire and modernity.5

CAUSES OF EXPANSION

European overseas expansion had begun in the fifteenth century with daring Portuguese and Spanish explorers like Vasco da Gama, later joined by Dutch, British, and French seafarers. This initial wave of colonialism was by and large coastal and commercial, driven by private concessions such as the Dutch East India Company. It concentrated on extracting precious metals such as silver, which were getting scarce in Europe, or on collecting spices, tea, and coffee that could not grow there. Much of the trade was also in involuntary labor, reduced to slavery, for plantation agriculture in the Caribbean or the Americas. In more hospitable regions of North America and Australia, where the climate was moderate and there were no diseases like malaria, settlement colonies also developed; these attracted religious dissidents, land-hungry peasants, and criminal outcasts.6 This older colonialism established vast transoceanic empires, but with the rise of free trade and the abolition of the slave trade around the first third of the nineteenth century, its energy was largely spent.

From the 1870s on a new imperialism developed, based on the dynamics of European modernization, that built on earlier trends but intensified penetration and control. The term “imperialism” originally criticized Napoleon III’s adventurous policy of building the Suez Canal, but once the shorter shipping route to India had turned into a “life-line of the British empire,” the word assumed a more positive ring. In the ensuing “scramble for Africa” that divided the continent among European powers according to the boundaries laid out in the 1884–85 Congo Conference in Berlin, the new imperialism acquired a different character from the older pattern of colonialism. Though still propelled by scientists, missionaries, and traders, it was quickly taken over by governments and involved claiming entire territories, penetrating the back country beyond the coastlines, and establishing military security as well as bureaucratic control. This more invasive form of domination allowed plantation owners, mining companies, financial investors, and shipping lines to pursue their profits within a framework of European hegemony.7

In the 1920s the American political scientist Parker T. Moon tried to define the essence of this “new imperialism” by highlighting its political aspects. He considered it “an extension of political or economic control by one state over another, possessing a different culture or race, supported by a body of ideas, justifying the process.” Instead of focusing on economic exploitation, this classic definition stressed a direct or indirect form of control, a difference in culture and race as well as a rhetoric promoting expansion. A more recent definition paints a more complicated picture: “Empires were characterized by huge size, ethnic diversity, a multitude of composite territories as a result of historic cession or conquest, by specific forms of supranational rule, by shifting boundaries and fluid border-lands and finally by a complex of interactive of relationships between imperial centers and peripheries.” This description has the advantage of encompassing not only the maritime empires like that of Great Britain but also the contiguous land-based empires like those of Russia, Turkey, and Austria-Hungary.8

The renewal of European overseas expansion and territorial conquest was propelled by several complementary aspects of modernity. One often-overlooked motive was scientific curiosity in exploring the geography of unknown territories, such as David Livingstone’s attempt to discover the sources of the Nile, and to map their resources so as to exploit them. Engineers were also excited about the challenges of building harbors, bridges, railroads, telegraph lines, or canals in difficult environments in order to tame an unruly nature so that Europeans could penetrate into and profit from their new possessions.9 Moreover, a whole new scholarly discipline of ethnology developed in order to study representatives of presumably more primitive cultures, describing their strange customs and collecting their religious or secular artifacts. When these anthropologists brought some of the products and sometimes even peoples of exotic lands back home, they exhibited them in newly founded ethnology museums so that European visitors could marvel at their strange customs—and feel superior to them.10

Economic interests undoubtedly played a major role as well in propelling adventurers into foreign continents in the hope of making a fortune abroad. With the advent of mass production, industries such as textiles looked for new markets beyond Europe, since the meager wages paid to their own workers kept consumption low. The rise of new technologies such as electricity and automobiles also required raw materials that were not available in the Old Continent such as copper for wiring or rubber for tires. Moreover, the spread of prosperity expanded the available capital of speculators intent on making investments where the return might be double or triple that of the yield at home, even if the ventures were much riskier. These incentives motivated businessmen to establish plantations or mines supervised by whites who ruthlessly exploited native labor in order to turn a profit. To the shopper in the European metropolis, some goods like coffee, tea, bananas, oranges, and chocolate were offered in stores as “colonial wares.”11 Since creating the necessary infrastructure was expensive, most colonies operated at public cost for the sake of private gain.

Somewhat less clear are the social dynamics, connected to the rise of the masses, that lay behind the drive toward empire. One element was the fear of overpopulation that resulted from rapid increases in the last decades of the nineteenth century, dramatized by Hans Grimm’s novel People without Space (1926). However, hopes for bettering one’s life through emigration to the colonies were often disappointed owing to the hardships involved in such a move, so that the expectation of Europe’s governments to clear their domestic slums through imperialism rarely panned out. Another aspect was the fierce propaganda of pressure groups such as the colonial leagues or navy leagues financed by commercial interests such as shipping lines or importers of colonial goods. With posters, pamphlets, and lectures these associations painted a glowing picture of individual opportunity in the empire, ready for the taking.12 Finally, some European elites also sought to deflect the increasing pressures for social reform and political participation through imperial expansion, thereby making a lowly proletarian feel superior to a foreign prince.

The cultural impetus of the new imperialism was the paradoxical project of a “civilizing mission” or mission civilisatrice, understood as a right and duty to elevate lesser peoples to the European standard. Originally, this motive comprised the missionary aim to bring the blessings of Christianity to heathens so that they might also have a chance for salvation. In its secular guise developed during the Enlightenment, the concept also involved the propagation of a rational way of life, which Europeans regarded as the apex of human development. In his poem titled “The White Man’s Burden,” the British writer Rudyard Kipling provided the classic rationale for this effort by enjoining youths “to serve your captives’ need.” But calling the colonial peoples “half-devil and half-child” betrayed a deep-seated arrogance and racism that contradicted the altruistic spirit of lifting so-called natives “out of bondage” by spreading knowledge, health, and civility. While claiming to disseminate a humanitarian vision of modernity, the civilizing ethos went only so far as to make the colonized function in the imperial system, denying them full equality.13

A final cluster of causes of the new imperialism involved the rivalry between the great powers, which incited countries to compete with each other in conquering and exploiting colonies lest they be left behind. A social Darwinist outlook saw international politics as a struggle for survival, forcing governments to match any presumptive gain in power or territory of a neighbor with similar increases of their own. Once an empire had been established, there was also the strategic necessity of geopolitical defense of one’s possessions, demanding coaling stations for naval resupply or the annexation of further lands to improve the military position of a frontier. In 1890 the American admiral Alfred T. Mahan formulated this credo of “sea power” persuasively, arguing that empires like the British rose to dominance due to their superiority on the oceans, thereby propagating a “navalism” that dovetailed well with imperialism. Such views coalesced into a sense of national vitality, which argued in biological metaphors that the future belonged to young and growing as opposed to old and declining nations.14

The rise of the new imperialism in the last decades of the nineteenth century therefore resulted from the dynamism of European modernity, which propelled outward expansion. Many of the motives—such as scientific curiosity, capitalist greed, and mass politics—were driving forces of modernization. Also most of the tools of domination—such as steamers, railroads, telegraphs, and machine guns—were new technological inventions that made European countries more powerful, allowing their navies and armies to conquer new territories and bureaucracies to establish administrations to control them. Moreover, the humanitarian vision of “civilizing” the world was a modern European invention, intending to reshape the entire globe in its own “progressive” image. Taken together, these forces made the new imperialism a self-propelling process that proved so unstoppable as to overcome even the reluctance of continental traditionalists like Prince Otto von Bismarck, who had vowed “as long as I am imperial chancellor, we shall not pursue a policy of colonialism.”15 The result was the scramble that divided Africa and the rest of the not-yet-modernized globe.

PATTERNS OF DOMINATION

In hindsight it still seems baffling that a small number of Europeans managed to seize control over far more numerous peoples and vast territories by making use of the advantages of modernity. Usually the imperialists merely transformed the previous penetration of explorers, traders, or missionaries into political control by intervening in local conflicts. In India several tens of thousands of Englishmen managed to govern an entire subcontinent populated by tens of millions through a mixture of political alliances with powerful local rulers (Raj) and the occasional use of military force against their foes. In German East Africa a few thousand administrators and soldiers succeeded in subjecting a huge area, inhabited by several million tribesmen, by allying with members of previously defeated tribes. When temporary setbacks occurred, the metropole would provide additional resources or soldiers to increase the pressure. Once in power, Europeans relied on superior organization to establish peace between tribes, using economic incentives and symbolic rewards to motivate the colonized to accept their dominion.16

Another method was the ruthless use of military force, leading to the exceptional violence of colonial wars in which technology and organization compensated for strategic disadvantages. For instance, in the Battle of Omdurman on September 2, 1898, 8,000 British regulars, supported by 17,000 local auxiliaries, routed almost 50,000 dervishes to reestablish control over the upper reaches of the Nile. While General Sir Herbert Kitchener had powerful artillery, machine guns, and gunboats at his disposal, the caliph Abdullah’s more numerous forces were equipped only with spears, sabers, and muzzle loaders. As a result about 10,000 of his men were killed, 13,000 more wounded but subsequently murdered, and another 5,000 taken prisoner. In contrast, the British suffered only 47 dead and 382 wounded in the fighting. Due to European superiority, the combat was “not a battle, but an execution.” Reported by a young Winston Churchill, the smashing victory became a self-reinforcing legend of empire. Brutality against the inhabitants was therefore an essential part of establishing control with limited forces over larger numbers of natives.17

Another strategy was the opening of new possessions to trade beyond local exchanges by constructing an infrastructure so as to exploit colonial resources more efficiently. To allow steamships to dock, harbors such as San Juan in Puerto Rico were dredged, and quays, cranes, and customhouses were built to facilitate the transfer of bulk goods. At the same time, the interior was made accessible by converting paths into roads suitable for trucks or constructing railroads capable of carrying larger numbers of people and products greater distances. Trading posts would be established along such routes for supplying white settlers and selling mass-produced goods to local inhabitants. In the Congo plantations replaced subsistence agriculture in order to grow coffee or bananas in sufficient quantities to be profitably shipped. In South Africa various kinds of mines were dug in order to extract precious stones such as diamonds or metals such as copper or silver.18 Offering a few aspects of the European lifestyle to some of the colonized, these innovations intensified the exploitation of resources and linked colonial production to world markets.

This imperial system relied on a rigid racial stratification of colonial society that clearly delineated the rulers and ruled. In principle, colonial society was divided into a white ruling class, an intermediary group of subaltern helpers, and finally a bottom rung of exploited local labor. The reality was, of course, often more complex, since a parallel local hierarchy existed that had to adapt to the new authority relationships by being fundamentally reshaped or gradually dissolved. Crossovers between both realms also complicated the maintenance of distinctions, since some Europeans inevitably “went native” whereas sons of the local elite, once trained in European universities, no longer wanted to play inferior roles. While some whites bonded to the landscape or established affection for local peoples, romanticized in memoirs like Karen von Blixen-Finecke’s Out of Africa, the basic relationship between colonizers and colonized remained highly unequal.19 Moreover, a complex set of customs, apartheid laws, or the use of physical force saw to it that both worlds would generally remain separate.

Confident of bringing progress, Europeans superimposed their own institutions, manifested in colonial buildings that were a curious mixture of their own and local styles. The center of an administrative capital such as Windhoek was usually the governor’s palace, a gleaming white structure with verandas and gardens, suitable for administration as well as representation. Barracks to accommodate military or police forces sufficient to maintain order were also needed. Since colonizers often fell ill, they had to build a hospital, staffed with white doctors and helped by black nurses. Then there were churches to minister to the colonizers and to the newly converted. European-style schools for the children of the new rulers also had to be erected, all the way from primary to secondary establishments. Finally, in especially salubrious areas. villas surrounded by greenery and staffed by numerous servants were constructed to house the whites. Bypassing the hubbub of native towns, these representative buildings of the European way of life created parallel settlements in which colonizers and colonized barely interacted.20

The degree of European control depended on both the pressure of imperial modernization and the level of development of the local culture. Where there was only tribal organization, the colonizers were able to take over completely, and attempts at rebellion were quickly crushed. Such a “complete dependence” characterized outright colonies like the Belgian Congo or Portuguese Angola. Where there were more developed local cultures, more complex religions, and stronger forms of political organization, European influence was more limited, allowing local structures to survive. Such “semiautonomous” regimes or protectorates existed in Egypt and Morocco, although they were formally part of the British and French empires respectively. Where the indigenous population had a long tradition of independence, considerable resources, and a high culture, these factors kept the colonizers from annexing the country, allowing imperialists only to establish coastal beachheads or exert political pressure. This loosest form of control in a “sphere of influence” was typical of China or Turkey.

European domination therefore rested on a complex mixture of imperialist power and local complicity. No doubt military force was important in the initial conquest and subsequent suppression of revolts, but it was not sufficient, because the colonies were too vast and the occupiers too few. In essence, the European generals, administrators, and planters inserted themselves into existing structures, replacing previous rulers or co-opting them into the new order, often leaving the lower levels of society largely intact. In doing so, the colonizers also used incentives such as distributing medals and titles or sharing some of the monetary gains in order to win cooperation. The establishment of military security, administrative control, and economic exploitation also required the use of local manpower in subaltern roles, which had to be trained in European procedures in order to function efficiently. The resulting colonial society was therefore a hybrid realm of exploitation and racial inequality, blending modernizing European influences with remaining indigenous traditions.

VISIONS OF EMPIRE

Beyond these structural similarities, the major European powers developed competing visions of empire, depending on their past, politics, and resources. Resting on sea power, the British Empire gathered the most extensive domains because it had begun in the seventeenth century. After salvaging control over Canada from the debacle of American independence, London managed to open up new settlement colonies in Australia and New Zealand. But the “jewel in the crown” was the Indian subcontinent owing to its vast wealth and large population, which provided the aristocracy opportunities for making fortunes. In order to safeguard imperial communication, Britain took over the Suez Canal of Egypt in the 1880s and defeated the Islamic Mahdi rebellion in the Sudan. In the scramble for Africa, London promoted a “Cape to Cairo” vision of a north-south axis of contiguous possessions, blocked only by the Portuguese, Belgians, and Germans. This paradoxical blend of economic exploitation, racial arrogance, and humanitarian rhetoric, while on the one hand abolishing the slave trade, was on the other hand quite successful at conquest and domination until running into territories already occupied by competitors.21

Combining personal profit with imperial ambitions, Cecil Rhodes was the quintessential British imperialist. Born in 1853 in Herefordshire into a vicar’s family, he was sent to Natal in 1870 to improve his health. During later stints of study at Oxford University, he imbibed the ethos of empire. Though he succeeded as a fruit grower, his breakthrough came with the creation of the De Beers Mining Company, which managed to corner the diamond market with the help of the Rothschilds. As one of the wealthiest English businessmen in Africa, he became prime minister of the Cape Colony, where he promoted racist laws, pushing blacks off their land. Trying to expand British control over all of South Africa, he promoted the Boer Wars against the Dutch settlers in Transvaal, hastening their defeat. Blending business with politics, his British South Africa Company pushed north, opening up the Zambesi Basin and creating another colony named Rhodesia, after him. Ultimately Rhodes, wanting Britain to rule the entire world, funded scholarships to entice top American and German students to join his quest by studying at Oxford and presumably absorbing the same imperial ethos. When he died in 1902, he was both admired and reviled.22

The French were the chief rivals of the British, since their colonial ventures had a similarly long history and geographical scope. Although they lost their North American possessions in the Seven Years War to the British and sold Louisiana to the United States, they managed to hang on to the West Indies. But the contradiction between the Enlightenment conception of human rights and the profitable practice of slavery in the sugarcane fields came to a head under Toussaint L’Ouverture’s revolt in Haiti. After this setback the French concentrated their efforts on “Mediterranean proximity,” seizing Algeria in 1830. During the Third Republic, France conquered a host of other North and Central African territories and established itself in Madagascar and Indochina. In contrast to the British, who migrated in substantial numbers to several parts of their empire, large numbers of Frenchmen settled only in Algeria, leaving the other colonies and protectorates to be ruled by a thin layer of administrators and soldiers. Colonial apologists like Jules Ferry believed in the mission civilisatrice, spreading French language and culture regardless of skin color.23 This promise attracted some indigenous intellectuals, even if its practice fell far short.

The lure of empire was so powerful that other newcomers also tried to accumulate their own overseas possessions. While declining countries such as Spain and Portugal sought to defend the remnants of once-extensive empires, rising nations like Imperial Germany attempted to grab whatever was left. Only unified in 1871, the Germans seized East and West Africa, Togo, Cameroon, and some smaller possessions in the Pacific. Since in Africa the Maji Maji and Herero engaged them in bloody wars, Berlin shifted its attention to the Balkans and the building of the railroad to Baghdad, seeking a sphere of influence in Turkey.24 Though the new Italian state failed in its attempt to conquer Abyssinia, it managed to seize Libya in 1911, seeking to recapture the glory of the Roman Empire. Pushing beyond its continental conquests according to “manifest destiny,” the United States also ventured into the Caribbean and the Philippines. Finally, rapidly modernizing Japan, having barely escaped outside control, now tried to establish its own Asian empire in Korea and Manchuria, defeating Russia in 1905.

The great landed empires of Eastern Europe were based on contiguous expansion but nevertheless showed many similarities to the overseas dominions. While the army played the central role and differences in religion and race between imperial and subjected peoples were often smaller, the structures of annexation, exploitation, and central control resembled the overseas pattern. The oldest and most vulnerable was the Ottoman Empire, also known as “the sick man of Europe,” since it had begun to lose its possessions by 1900. In their heyday the Ottomans were an advanced military power, conquering Constantinople in 1453 and subjugating territories from the Balkans to the Maghreb across the Near East and North Africa. Though Islamic in religion, they were nevertheless tolerant to the subject peoples as long as these paid taxes and provided sons for the Sultan’s elite fighting corps. By the nineteenth century, the Ottomans were increasingly threatened by Christian uprisings in the Balkans as well as by Arab insurrections. Hence in 1908 the Young Turk movement under Mustafa Kemal, called Atatürk, sought to modernize Istanbul in order to salvage the Turkish core.25

The even larger Russian Empire extended all the way from Warsaw in the West to Vladivostok in the East and from Finland in the North to the Caucasus Mountains in the South. The motives for expansion involved the usual mixture of economic interests in acquiring more resources, security questions of defending frontiers, and the weak organization of the neighboring territories. Since it was a land-based empire, the newly conquered regions were simply incorporated into mainland Russia, ruled autocratically by an all-powerful tsar, an imperial bureaucracy, and a huge army. The Russian ethnic core was inspired by an ideology of exceptionalism based on Greek Orthodox Christianity, claiming to represent the “Third Rome,” which was Moscow. In practice, the empire was a weak giant because its population, recently liberated from serfdom, remained largely agrarian and its aristocracy was ambivalent about whether it would be better to follow European modernization or reject it for its subversive tendencies.26 The middle class longed for greater participation in political decisions while an emerging intelligentsia attacked autocracy, orthodoxy, and hierarchy from within.

Often underestimated, the Habsburg Empire of Central Europe comprised a mixture of ethnic groups that lacked a clear majority. Its origin went back to the unification of the Austrian, Bohemian, and Hungarian crowns in 1526, which succeeded in fending off successive Ottoman onslaughts in the Balkans. During the Counter-Reformation the Catholic emperors ruthlessly suppressed Protestantism in their own lands and tried to defeat it in other German states in the Thirty Years War. Around 1900 the empire was held together by affection for its long-serving monarch, Emperor Francis Joseph, as well as by a multilingual army, a central bureaucracy, and a commercial middle class that cut across ethnic differences. Though the Austrian Habsburgs’ compromise with independence-minded Hungarians in 1867 had managed to restructure the Dual Monarchy, the rise of German and Czech nationalism boded ill for its future. On the one hand Vienna became famous as the capital of Jugendstil and psychoanalysis, but on the other it was also a hotbed of anti-Semitism. In dealing with the Balkans, Austria-Hungary could not decide between defensive and aggressive policies.27

European domination was therefore not a common enterprise but rather a competitive undertaking, avoiding war only through international conferences that settled conflicting claims. In general, the western overseas empires were more modern (i.e., developed economically and liberal politically) and possessed a stronger middle class. However, as a legacy of slavery their imperial projects created a deep contradiction between their social Darwinist racism toward the colonized and the development of citizens’ rights among their own populations. In contrast, the eastern landlocked empires were less industrialized and more autocratic, with most inhabitants still working on the land. Nonetheless, they, too, faced the need to modernize, which triggered a conflict between the claims of their own citizens to political participation and the demands for self-determination of the ethnic and religious groups subjected by them. While the edifice of empire still looked imposing at the turn of the century, the growth of anti-imperialist and nationalist independence movements would eventually bring it down.28

COLONIAL IMPACT

The impact of imperialism on the colonies was profoundly transformative, forcing a flawed form of modernization onto the reluctant subjects. Within a generation after the arrival of white colonizers the outward appearance of life changed profoundly, ranging all the way from the spread of Western clothing to the emergence of Christian symbols. The extent of the transformation varied, of course, with the level of development of the local culture and the degree of European power, triggering drastic changes in most of Africa while making a smaller impression on much of Asia, where resistance was stronger. Though some of the innovations were the result of formal compulsion by the new rulers, others developed through informal interactions between colonizers and colonized. The transformation usually began piecemeal in colonial centers but eventually spread to the entire territory, creating an unstable hybrid of old customs and new habits. Because the relationship was highly unequal, the results were also rather mixed, entailing both much brutal oppression and some humanitarian improvement.

The workplace was one problematic point of enforced modernity because it replaced traditional agriculture or crafts by toil in plantations or mines. Essential for the exploitation of these resources, male workers were usually conscripted by force, compelled to do backbreaking labor without the aid of machinery. Rather than following the rhythm of the sun or the seasons, they had to internalize Western concepts of time, with the clock or the siren determining the length of their workday. Moreover, they were forced to acquire European notions of labor discipline, working diligently until the assigned task was completed rather than taking breaks whenever they felt they needed them. For their efforts they were paid in kind or in money, barely sufficient for their survival. Whenever they slackened their labor or complained, they were brutally beaten by mostly white overseers who reinforced the racial hierarchy by doling out arbitrary punishment. In the colonies this general transition from traditional life to capitalist labor was aggravated through an even more ruthless exploitation of nature and people.29

The colonizer’s home, where most of the women’s work was done, was another place of unequal modernization. The elaborate colonial lifestyle required numerous servants to carry out the domestic tasks of cooking, cleaning, washing, gardening, and child care so as to afford the white mistresses a life of leisure. In order to function effectively, indigenous women quickly had to learn European middle-class virtues such as neatness, thrift, diligence, cleanliness, and punctuality. At the same time they needed to acquire enough knowledge of Western forms of clothing and food preparation so as to be able to fulfill their duties. While there was less physical abuse than in the fields, paternalism clearly kept servants in their place, and mistresses could be quite demanding and capricious. Moreover, sex was a continual problem since there were not enough white women to go around and domineering white males often impregnated local girls, creating a half-caste group of mulattoes caught between both races. But through social pressure white women quite effectively maintained their version of a color line in colonial society.30

The trading post was yet another modernizing space because it drew the local people into a monetary exchange system, albeit on rather unequal terms. Essential for supplying white settlers or engineers in the outback with their accustomed provisions, these outlets taught natives to replace traditional forms of trading goods with selling and buying for money. While in relatively developed economies local coins survived, in other places the currency of the colonizing country became the prime medium of exchange. The Western trader would offer his local customers basic implements such as metal pots and knives, seasonings such as salt, or pieces of cotton fabric as well as baubles for embellishment. In exchange he would acquire local products: cocoa beans, tea leaves, or whatever else could be sold in Europe as “colonial goods.” Sometimes other intermediaries—Indians in South Africa, Chinese in much of Asia—would fulfill the Western trader’s roles. But in general such trade was profoundly uneven, since indigenous people were at the mercy of the prices set by traders.31

The encounter with European culture in school was presumably more positive because it claimed to spread modern enlightenment among the ignorant locals. No doubt the initiation into reading, writing, and arithmetic had a liberating effect on illiterate African children, since it enabled them to access a world of learning and to meet whites on more equal terms. But much of the instruction took place in a foreign language, the tongue of the colonial teacher, especially in the higher grades. Moreover, the lessons generally celebrated the “mother country’s” past and present achievements, disregarding the attainments of local culture and creating an artificial world of the mère patrie. At the same time, the often rigorous secularism of the teachers ridiculed traditional customs as superstition, destroying the old faith without putting anything comparable in its place. While the shift to written texts opened up realms of knowledge, it also weakened long-standing oral traditions. No wonder that colonial intellectuals often complained about being alienated from their own heritage without feeling fully at home in a Western world.32

The mission also purported to be a place of benign communication, since its intent was altruistic, bestowing the blessings of Christianity on heathens. At the risk of their own lives, missionaries of various denominations labored hard to break local superstitions like voodoo or animism and to replace them with the hope of salvation in the hereafter. More effective than their teaching were works of charity like Albert Schweitzer’s hospital in Lambarene that combated local diseases and ministered to the poor to keep them from starvation. The baptism of converts was often a joyful act, since it initiated the new believers into a community of a more benign faith. But when Christianity faced more highly developed religions such as Islam, Buddhism, or Confucianism, it had difficulty making inroads, since it offered little spirituality that these did not already possess.33 Though codifying indigenous languages, missionizing was basically a condescending enterprise, presuming a superior religious insight. Moreover, the newly converted were often shocked to find out that the Europeans themselves hardly followed their Christian precepts.

The colonial office was a final instrument of bureaucratic modernization, designed to uphold European rule over a restless local population. In administrative bureaus, courts, police stations, and customhouses the colonizers had to deal with the colonized in order to assure the smooth functioning of their domain. If they wanted to survive within a white world, the colonized had to learn unfamiliar bureaucratic rules, foreign legal concepts, strange behavioral patterns, and novel economic regulations. Especially where there were only a few European administrators, the control of large territories and populations required the assistance of trained locals as lower officers who would be appointed as clerks, legal aides, policemen, and customs agents. In their work these subalterns increasingly realized that once they knew European procedures and laws, they could begin to use them for protecting their own interests.34 But paradoxically in order to learn such ways, “Westernized oriental gentlemen” had to collaborate in upholding European domination and therefore found themselves between both cultural fronts.

The colonials’ response to this exploitative modernization was therefore highly ambivalent, mirroring the contradictory nature of its mixed impact. Once the destabilizing impetus of colonization became clear, local elites rallied to defend their own traditions, sometimes in bloody uprisings, such as the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857, that were put down with great brutality. A more successful strategy was adaptation, a concerted effort to learn European ways so as to use them for the colonials’ own purposes. It helped that liberal colonizers allowed sons of the local elite to attend British or French universities in order to acquire the technical skills and cultural sophistication needed for transforming their native lands upon their return.35 In the more autocratic landed empires this process usually entailed complete assimilation to the ruling ethnicity, be it Turkish, Russian, German, or Hungarian. Both welcomed and rebuffed, the colonial intellectuals who were not content with inferior roles therefore resolved to use the very ideological appeals, organizational skills, and military techniques they learned from Europe in order to throw off colonial control.

CULTURE OF EMPIRE

Though this aspect is often overlooked, imperialism also had a considerable impact on the European countries, both speeding and hindering their own development. Some scholars argue that an “imperial culture,” propagating the necessity of empire and extolling its benefits for all of society, formed in the last decades of the nineteenth century. Claiming that there was little explicit teaching of imperialism in the school curriculum, other historians have countered with the thesis of “absent-minded imperialists,” which stresses that the impact of empire on the lives of average people in Europe was indeed minimal.36 A closer look at the evidence suggests that both readings might be partially correct: A strongly committed minority of enthusiastic imperialists was directly involved in running the colonies, benefiting from them and therefore defending their importance. The passive majority with little such contact accepted the existence of empire as long as it did not become a major burden on them. Yet a small but growing band of critics also began to object to the financial costs and ethical transgressions of imperialism.

Among those susceptible to the lure of empire, European scientists who ventured abroad in search of new objects of discovery were one important group. A whole host of different disciplines was involved: Geographers mapped previously “unknown” territories, geologists explored mineral deposits, biologists catalogued new species of plants and animals, ethnologists observed customs of “primitive cultures,” linguists transcribed local dialects, and medical doctors studied the causes of tropical diseases. While such research added non-European specialties to established pursuits, eventually these different subjects were combined in colonial institutes for teaching future imperialists. As Edward Said has correctly pointed out, this was a paternalistic gaze that reduced the strange “other” to an object of study. Moreover, it was the exotic difference that appealed to the general public in colonial exhibitions and newly opened ethnology museums. While many of the findings reinforced a sense of racial superiority, other research contributed to scientific discoveries that could benefit colonized peoples—making it possible, for instance, to fight tropical diseases.37

Businesspeople who profited from trade with the colonies were another influential set of advocates of imperialism. Some were the owners of shipping lines or railroads that carried goods and mail, thereby assuring communication between the home country and the colony. Others were the growers of spices, coffee, or fruit, as well as their retailers in Europe who depended on a steady supply of such colonial goods. Many companies sought precious minerals such as diamonds or raw materials such as copper to be refined and incorporated into countless products they sold to metropolitan shoppers. Moreover, manufacturers of mass-produced textiles and implements like pots needed the colonial markets in order to expand their production beyond what they could distribute at home.38 Finally, even some ordinary people looked to the colonies either to make their fortune by working in imperial trade or to settle permanently abroad. Though liberal skeptics argued that these goals could be achieved more cheaply by free trade, imperialists insisted that it was necessary to have political control.

Government employees who could hope for advancement by serving abroad constituted another imperial pressure group. Navy and army officers especially looked forward to foreign adventures and counted on faster promotion than could be attained at home. In the colonies they could try out new gunboats or artillery on hapless subjects without observing the same restrictions applying to more civilized warfare in Europe. At the same time empire also offered ample opportunities for officials who might be stuck in middling ranks and could thereby leap ahead, lording it over the colonized with less-constrained authority. Sometimes these might be family misfits, sent overseas as punishment for a scandal to redeem themselves if no new shame attached itself to their name. No doubt in some postings there was the risk of disease and death, but a lavish lifestyle tended to compensate for such dangers. While scientific discovery and economic development contributed to modernizing Europe, the military and bureaucratic side of imperialism tended to reinforce conservative power structures.39

Those altruistic individuals who went to the colonies in order to help the indigenous people to improve their lives were a final group of pro-imperialists. Many missionaries, sent by various denominations, were motivated by a desire to bring the spiritual consolation of Christianity and to reform the morals of the local population. Similarly some doctors and nurses who staffed colonial hospitals also sought to alleviate pain and suffering among people who often lacked the scientific knowledge and the pharmaceutical means to combat disease. Some of the teachers who were willing to work in the imperial schools wanted not only to escape from the boredom of their continental lives but also to spread enlightenment among illiterate and superstitious locals. While these humanitarians also firmly believed in the superiority of European civilization, they were willing to undergo considerable privations in order to share its benefits. In contrast to the exploitative aspects of businessmen and administrators, these altruists gave imperialism a more humane face, blunting some of the criticism.40

Most of the Europeans who had little direct contact with empire were willing to tolerate it as long as it promised to bring more benefits than costs. In the metropoles, some inquisitive people might attend a scientific lecture, listen to an adventure story, or marvel at an exotic exhibition. Many more would buy colonial wares for daily consumption without a particular concern about their provenance. Others yet would hear political speeches celebrating new acquisitions or read imperial items in the newspaper with a sense that these colonies were interesting but far away. Or they might be asked in a church service to contribute to a missionary fund. On the whole, these slight contacts produced an awareness of a larger imperial scope beyond the nation-state but little willingness to make sacrifices for it. Europeans might be proud that their flag flew over possessions around the globe, like la France d’outre mer, but needed to be convinced by imperial enthusiasts that the whole enterprise was worth it. Even skeptical members of the “underclass” at home could feel themselves included as part of the “ruling class” in the colonies.41

Toward the turn of the century voices of criticism nonetheless grew stronger, thus calling the entire imperial project into question. These strictures were usually triggered by cases of economic speculation, instances of military brutality, or scandals due to administrative corruption. Free traders wondered whether commerce could not flourish without political possession. International commentators worried that confrontations between imperial powers, such as the encounter between Sir Herbert Kitchener and Major Jean-Baptiste Marchand in Fashoda in 1898, might lead to a European war. Spokesmen from the rising labor movement charged that the imperialist jingoism was distracting attention from the necessary reform of domestic problems. Moralists railed against debilitating vices such as opium, imported from the colonies. Sympathetic observers like Sir Roger Casement exposed the inhuman treatment of the natives in the Congo, leading to its being taken away from the Belgian king. Finally, colonial intellectuals also pointed out the glaring discrepancy between European professions of civility and practices of racist prejudice and economic exploitation. Increasingly, empire was acquiring a bad name.42

During its prime the “culture of empire” was nonetheless strong enough to deflect such attacks and to reinforce a popular imperialism that considered colonies the natural reward for European superiority. To counter the criticism, imperialist interests groups such as the navy leagues, army leagues, and colonial leagues as well as the missionary societies issued a stream of propaganda in posters, pamphlets, and speeches that defended the benefits of empire. It took a concerted effort to popularize the Congo and make the Belgians, except for the socialists, into proud imperialists.43 At the same time the cultural establishment was pervaded by imperialist ideas, since children’s authors spun adventure tales, playwrights used imperial settings, and journalists wrote captivating reportages. The rapid international spread of the Boy Scouts, founded in 1907 by General Robert Baden-Powell, illustrates that the quasi-military training of boys for imperial tasks proved attractive everywhere. This diffusion of imperialist sentiment infected wide circles with a powerful blend of nationalism, militarism, and racism that would soon tear Europe itself apart.

EUROPEAN HEGEMONY

In retrospect it is difficult to recall the extent of the European domination of the world, because it has been shattered so completely that only a few traces remain. Yet any schoolchild who looked at a map in 1900 saw the globe colored in different hues, showing virtually all territories in Africa, Asia, and Australia under imperial control, with even China divided into spheres of influence. While British, French, German, Dutch, Belgian, and Italian children had to memorize the names and capitals of distant dependencies, the Portuguese and Spanish basked in memories of their earlier empires. In Istanbul, St. Petersburg, and Vienna pupils were instead required to list faraway provinces, peopled by different ethnic groups and engaging in strange religious practices.44 The excitement of acquiring possessions was so strong that it even drew latecomers, notably the United States and Japan, into the race. The result was the establishment of a system of competing empires around the globe, centered on European states that were national and imperial at the same time.

The dynamic force that propelled this new imperialism by providing the motives, tools, and organization for expansion was European modernization. While scientific curiosity drove exploration, technological invention produced the steamships, telegraphs, and machine guns that allowed communication and control. Hope of profits motivated investment abroad, while the accumulation of capital offered the means to fund imperial ventures. Search for advancement motivated individuals to serve in the colonies or emigrate permanently, while legal codes established a framework guaranteeing white supremacy. The emergence of an efficient form of governmental organization, usually associated with the nation-state, was also crucial for the political implementation of imperial dreams. Powerful militaries using technical weapons systems were needed to conquer and hold territories, while efficient bureaucracy was necessary to administer the imperial domains. Though the symbolic trappings of empire remained neofeudal, the sources of metropolitan power were distinctly modern.45

Map 1. The extent of European imperialism, 1900. Adapted from Maps.com.

The ensuing Europeanization of the world was therefore an unequal form of modernization, using a mixture of compulsion and incentive to transform the colonies. Scientific penetration, economic exploitation, colonist settlement, and political control all required the construction of an infrastructure of harbors and railroads, plantations, mines, and markets as well as administrative centers on a European model. Moreover, the exploitation of local labor also demanded a social and cultural transformation of the indigenous population, conveying the rudiments of literacy, implanting work discipline, spreading hygiene, and even preaching the blessings of Christianity. This multilevel onslaught of Western modernity destroyed traditional outlooks and behaviors, dissolved social customs and hierarchies, and profoundly unsettled the colonized peoples because it came in a violent and repressive guise that left them little choice but to comply. But some of the imported changes also offered access to European knowledge and culture, providing ideologies and techniques that frustrated colonial intellectuals would eventually use to challenge metropolitan control.46

Europe itself was also profoundly transformed by imperialism, which seemed a beneficial form of modernization by creating new wealth, institutions, and practices. London, Paris, and Berlin witnessed the building of new colonial offices, scientific institutions, missionary headquarters, shipping agencies, and land bureaus whose business was the connection to the empire. Zoos full of strange animals such as elephants, botanical gardens filled with exotic plants such as orchids, and ethnology museums containing strange artifacts offered Europeans glimpses of a foreign world without their actually having to go there. Exchanges traded stocks in colonial ventures, creating those great fortunes that manifested themselves in imposing Victorian mansions and town houses. Stores sold precious gems as well as colonial wares, allowing the display of imperial objects and forming new consumption habits such as the drinking of coffee, tea, and cocoa. In the busy streets, people of different skin color, practicing different religions, and speaking different languages jostled one another, and in hotels strange guests arrived wearing Indian saris or Chinese silks.47 Faded snapshots in crumbling newspapers suggest that imperialism had penetrated European society to a considerable extent.

By its inherent brutality imperialism also fueled those destructive tensions of modernity that would eventually become its own undoing. In the international realm the race for colonies triggered a series of severe crises between the great powers, while in the colonies the resentment of subject peoples produced a chain of ugly colonial wars. Domestically, the celebration of empire fostered a climate of jingoism and racism that pitted European countries against each other and spread hatred between members of different ethnic or religious groups. In the land-based empires, efforts of the ruling nationalities to transform their multiethnic domains into more homogeneous nation-states inspired their subject groups to form national liberation movements that clamored for autonomy. In the overseas colonies the discrepancy between the professed civilizing values and repressive practices of the colonizers led intellectuals to agitate for independence from European control. Just when the edifice of imperialism looked most imposing, those cracks began to appear that would first make the land-based, and eventually also the overseas empires, collapse.48