DEMOCRATIC HOPES

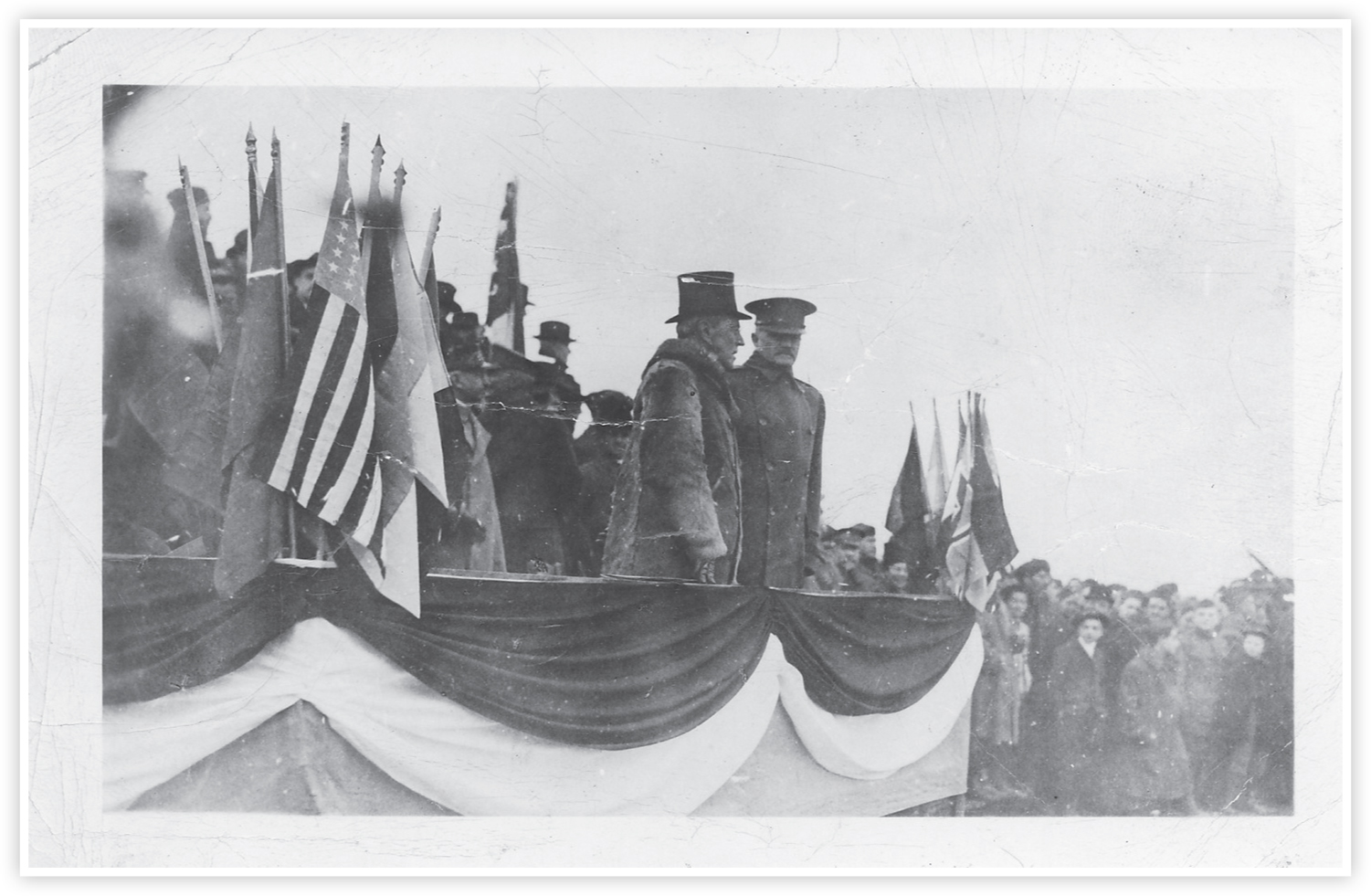

President Wilson reviewing troops, 1918. Source: Woodrow Wilson Presidential Library.

On January 8, 1918, Woodrow Wilson addressed a joint session of Congress with a democratic program that sought to counter Lenin’s revolutionary message. With great eloquence, the president proposed “fourteen points,” prepared in secrecy, that outlined a path toward making the world “fit and safe to live in” by ending the Great War. Not being a party to secret interallied agreements, the former law professor appealed to the war-weary peoples on both sides of the front with proposals that encapsulated progressive thinking about the preconditions for a more peaceful world. His first demands centered on open diplomacy, freedom of the seas, free trade, and disarmament—noble sentiments that would also benefit American interests. The next points outlined territorial conditions that favored the Entente without humiliating Germany needlessly—the evacuation of Russian territory, the restoration of Belgium, and the return of Alsace-Lorraine to France—while promising “autonomous development” to Austrian and Ottoman subjects. The capstone of such “a just and stable peace” was to be “a general association of nations”1

As a representative of democracy, the American president cut an imposing figure, looking both stern and inspiring. Hailing from a Scotch-Irish family, he was a sober Presbyterian but also an inspiring public speaker. After obtaining a doctorate in law from Johns Hopkins University, he had joined the Princeton University faculty and written about congressional government. Becoming its president in 1902, he had expanded the faculty and modernized the curriculum, calling on students to dedicate themselves to the service of the nation. Entering politics as a member of the progressive wing of the Democratic Party, he had been elected governor of New Jersey in 1910. Only two years later he had succeeded in winning the presidency as a result of his reputation for personal honesty and willingness to engage in reforms, formulated in his program of “New Freedoms.” In 1916 he had been reelected to a second term, largely because he had kept the country out of the war. As a democratic theorist and an experienced politician, Wilson brought the idealism of the progressive movement to the task of pacifying war-torn Europe.2

To supersede traditional power politics, the president’s “war aims message” addressed three problem areas that he considered essential for creating a stable postwar order. First, since the returning soldiers claimed participation rights as citizens, internal peace demanded the expansion of parliamentary self-government. Responding to the rise of mass politics required domestic reforms in Western Europe and revolutionary changes in Central and Eastern Europe. Second, inspired by the spread of national aspirations, the emerging nationalities clamored for a chance to create-nation states of their own. This goal ultimately implied the dissolution of the multiethnic tsarist, Austrian, and Ottoman empires. Finally, the advance of transnational trade and communication called for an institutionalization of international cooperation in order to make the new countries work together. Ironically this imperative required limiting the nation-states’ recently gained sovereignty. These principles envisaged a fundamental revision of the domestic and international order—but they were more moderate than the Soviet program because they did not necessitate a social revolution.3

Though some skeptics were horrified, President Wilson’s program inspired widespread hope among the exhausted populations of the belligerents by offering a compromise to end the war. Defenders of the traditional order like the British diplomat Harold Nicolson condemned Wilson’s new diplomacy of “open covenants of peace” as naive, incapable of producing lasting solutions. Bolshevik radicals like Leon Trotsky considered this bourgeois program too halfhearted to get at the social roots of the imperialist problem.4 But the democratic Left on both sides of the front thought the territorial provisions constructive, since they suggested a moderate way to break the deadlock of excessive war aims. Offended by the chauvinist rhetoric of war propaganda, critical intellectuals were also intrigued by the innovative principles, which presented a blueprint for constructing a lasting postwar European order. Finally, once they realized that they could no longer win the war, German leaders grasped at Wilson’s outstretched hand to avoid the harsher terms that they feared from their continental antagonists.5

The Wilsonian vision formulated a liberal path toward modernity that sought to restore hope in progress through democratizing Europe. Responding to the popular claims for democracy, his advocacy of self-government intended to reenergize the drive for parliamentary systems that would allow the masses to participate in politics. At the same time the American president’s support of self-determination tried to liberate subject populations from autocratic control, encouraging the creation of ethnically based national states. Embodying aspirations of bourgeois internationalism, the plan of a League of Nations attempted to prevent another world war and reinforce the ties of peace by creating an institution to adjudicate disputes. On the one hand, this inspiring vision was directed against autocracy, championing the replacement of the land-based empires by democratic nation-states. On the other hand, Wilson’s approach offered an alternative to Bolshevik social revolution by insisting on free trade and private property.6 This liberal program therefore proposed a moderate blueprint for peace and prosperity.

GERMAN COLLAPSE

For democracy to spread, the authoritarian alternative of modernization, represented by the Central Powers, first had to be defeated on the battlefield. The Allies ostensibly fought for universal values of Western civilization, interpreted as individual liberty, parliamentary government, and market competition, even if imperialism, racism, and exploitation marred their practice. In contrast the German-led coalition claimed to embody a deeper version of Kultur, characterized by bureaucratic authority, military efficiency, and social welfare. Already in 1915 the Norwegian-born sociologist Thorstein Veblen pointed out the discrepancy between the scientific and technological modernity of Imperial Germany and the lagging development of self-government, which retained ultimate power for the kaiser and gave the military a larger voice than in the democracies. Instead of treating the West as standard and arguing that this difference represented a “partial modernization,” it is more illuminating to view the German model as an alternate path within the broader western tradition.7 Responding more flexibly to the strategic challenges, social leveling, and erosion of authority, the liberal variant ultimately proved superior to the authoritarian version of modernity.

While the Allied leaders could confidently wait until their material advantage prevailed, the German Supreme Command risked a desperate gamble to snatch victory from the jaws of defeat. Having been intent on strengthening the antidemocratic forces at home by conquest in the East, strongman Erich Ludendorff saw the Russian collapse as a chance to move fifty divisions to the West before American reinforcements arrived and the morale of his troops crumbled. He believed that “the situation among our allies as well as the condition of the army demanded an offensive which would bring a quick decision.” On March 21, 1918, the German army launched a series of four attacks on the western front, hoping to divide the British and French and capture Paris. With new tactics such as shock troops and rolling artillery bombardments, the attackers crossed the Allied trenches and made impressive gains, creating the illusion of repeating the initial advance of 1914. But the final offensive on July 15 failed to achieve its aim, since the Allied lines were dented but never completely broken. By gambling on victory the Germans lost, since they spent their last reserves.8

The failure of the Ludendorff offensive hastened the end of the war in the West and South, because it returned the strategic initiative to the Allies. While both sides incurred roughly equal losses, the Central Powers had greater difficulty in replacing men and weapons than the Entente. At long last the Allied resources in war matériel and manpower proved stronger than the military training of Berlin and its allies. With the German submarine threat blunted by the convoy system, increasing amounts of shells, guns, trucks, and other weapons reached the western front. Moreover, converted passenger liners shipped growing numbers of newly trained troops, eager to fight, from the United States to European battlefields. In contrast to the dispirited French and British veterans who merely sought to survive, farm boys fresh from Iowa still obeyed orders when told to “go over the top” and attack the German lines, no matter what the cost. Finally, advances in military technology such as the introduction of about eight hundred new tanks as an infantry-support platform also turned the tide.9

The Allied Hundred Days Offensive of the summer and fall of 1918 proved decisive in bringing the war to a surprisingly swift conclusion. Already in mid-July, French general Ferdinand Foch had mounted an attack close to Reims that recaptured some lost ground. But when five hundred British tanks struck at Amiens, they overran weakened German divisions and forced a hasty retreat, making August 8 a “black day for the German army.” This unexpected defeat convinced Ludendorff that the war could no longer be won, since not only were his divisions depleted but also his soldiers were listening to the peace propaganda of the radical Left and were increasingly unwilling to fight. With renewed vigor the attacking Allies reconquered the German salients of the spring, forcing the deteriorating enemy forces to retreat to the fortified Hindenburg Line. Though suffering heavy casualties, the combined Allied assaults eventually breached that desperately defended trench system as well. By the end of September the Entente’s unstoppable advance and the crumbling of Berlin’s allies made clear to the Supreme Command that the war was lost.10

The realization of impending defeat, long hidden by positive military bulletins, finally forced the leadership of the German Empire to sue for peace. In July 1917 a critical Reichstag majority had already voted for a resolution that called for a peace “without annexations and indemnities.” Because of their military failure, the quasi-dictators Hindenburg and Ludendorff could no longer prevent calls “for a complete change of the system” toward parliamentary government led by a reformist chancellor, Prince Max of Baden. Admitting that “the continuation of the war should be abandoned as hopeless,” they had to accept a civilian proposal “to approach President Wilson with the request for an armistice.” Feeling betrayed by their officers, German sailors and soldiers began to abandon their discipline and also demand an immediate cessation of hostilities.11 As a result the German army, though still occupying parts of northern France and Belgium, had to capitulate because it was unable to continue the fighting. A combination of Wilsonian hopes from above and Leninist propaganda from below ultimately made Berlin call for a cease-fire.

Signed in a railroad carriage near Compiègne, the armistice agreement of November 11, 1918, only terminated the official hostilities; it did not end international and domestic violence. The stringent military terms of withdrawing the German forces to their home bases, interning the navy, and surrendering all heavy war matériel were designed to prevent a renewal of armed resistance.12 But the uncertainty of boundaries in Central Europe and the Balkans spurred continued fighting by Free Corps (local militia units) seeking to secure territory in mixed ethnic areas. Moreover, the Russian Civil War, Allied intervention in Russia, and the Soviet-Polish War extended major combat in Eastern Europe for several years. Some regions that wanted to secure their independence, such as the Ukraine, changed hands several times. At the same time communist uprisings in Budapest and Munich as well as right-wing military coups such as the Kapp Putsch in Berlin projected violent conflicts into the domestic arena. Contrary to the mythology of Armistice Day celebrations, it still took almost half a decade for the last fighting to subside in Europe.13

After the nightmare of war had finally ended, winners and losers alike faced an enormous challenge in converting the machinery of war back to peacetime uses. Estimates suggest that some 10 million soldiers had died in combat and another 23 million had been wounded while roughly 7.5 million civilians had perished, creating an irreparable demographic loss.14 On the one hand, demobilization involved the complicated logistics of bringing troops home and getting them out of uniform. The task of turning trained killers into nonviolent civilians also turned out to be quite difficult. In order to provide jobs for veterans, regulated economies had to shift from war production back to the making of consumer goods, reconverting steel helmets into cooking pots. On the other hand, expectations for a peace dividend were enormous in the victorious countries, while the defeated had to accept the losses incurred. Citing their physical and mental sacrifices, returning soldiers as well as women of the home front demanded and won greater recognition by gaining more political rights and social services. The transition to peace proved difficult, since the elites wanted to restore prewar hierarchies, while the suffering masses called for democratic reform or socialist revolution.15

DEMOCRATIC PEACEMAKING

The conditions of the armistice, negotiated between the United States and the Entente, already foreshadowed the contradictory character of democratic peacemaking. Prompted by a desperate Supreme Command, the German government had appealed to Wilson in early October for an armistice on the basis of his fourteen points. But the president made it clear in several notes that German troops would have to withdraw completely from Allied territory and that the kaiser would have to abdicate. Negotiations between Wilson’s emissary Colonel House, Clemenceau, and Lloyd George were even more complicated, since the French and British leaders initially refused to be bound by the American peace conditions. However, when they learned of a softening interpretation worked out by “The Inquiry,” a group of U.S. academics and diplomats preparing the peace conference, the European Allies accepted the fourteen points, believing that they could modify them to suit their own interests. The tough military provisions were drafted by General Foch, including the occupation of the left bank of the Rhine and the continuation of the blockade.16

This pattern of blending Wilsonian principles with nationalist aims continued during the actual Paris Peace Conference. Begun in earnest on January 18, 1919, the negotiations were dominated by the leaders of the three major “Allied and Associated Powers,” Clemenceau, Lloyd George, and Wilson, although representatives of Italy, Japan, and a host of smaller nations also sought to influence the decisions. Most specific terms were hashed out in committees, besieged by petitioners like Ignace Paderewski, pleading for the restoration of Poland, or Tomáš Masaryk, calling for the creation of Czechoslovakia. The French public wanted to obtain security against renewed German aggression through territorial gains, diplomatic assurances, and economic concessions. British opinion was more interested in retaining naval supremacy and gaining additional colonies, while the U.S. delegation focused on the creation of a Covenant of the League of Nations. Not consulted about any of the provisions, the representatives of the new democratic Germany were confronted with a final draft and forced to sign by an ultimatum on June 28.17

The Versailles Treaty imposed considerable losses on Germany of one-seventh of its prewar territory and one-tenth of its population. France regained the provinces of Alsace-Lorraine, assumed control over the coal-rich Saar Basin, and insisted on a fifteen-year occupation of the left bank of the Rhine. Similarly ignoring ethnic composition, Belgium obtained new territory in Eupen-Malmedy. In Schleswig there was a plebiscite in which the northern third voted for a return to Denmark. In the East, the conflict between national origin and free access to the sea was resolved by turning over the ethnically mixed province of West Prussia to an independent Polish state, making the German port of Danzig an international city, thus cutting off East Prussia from the Reich, and by dividing the coal mines of Upper Silesia mostly according to the results of a plebiscite. Moreover, the port city of Memel and its hinterland were given to Lithuania. As neither the German-speaking Sudetenland nor Austria was allowed to join the Reich, nationalists could argue that self-determination was only applied to Germany’s detriment.18

The other members of the Central Powers were compelled to accept even more draconian terms, since new national states were primarily created at their expense. In response to nationalist agitation, the treaties of St. Germain and Trianon broke up the Austro-Hungarian Empire, claiming to divide the ethnically mixed areas of East-Central Europe according to national lines. This principle left a small ethnically German state of Austria and an equally reduced Hungary, with three million Hungarian speakers under the control of its neighbors. The Treaty of Neuilly forced Bulgaria to cede some border provinces to the newly constituted Yugoslavia. The Treaty of Sèvres dissolved the Ottoman Empire, severing its Arabic provinces as League of Nations mandates and retaining only an ethnically Turkish rump. This decision created a bloody conflict with Greece ended only by the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, which stipulated an exchange of population, expelling hundreds of thousands of Greeks from Asia Minor and Turks from Greece. Geographic ignorance and special pleading created new borders that remained a source of hostility.19

The East European settlement was also hampered by the absence of Russia from the conference table due to the fear of revolutionary contagion by communism. In principle, the Allies repudiated the punitive Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, but in practice they were compelled to withdraw their interventionist forces and accept some of its provisions by recognizing the independence of Finland and the Baltic states. The peace conference instead supported the creation of three new barrier states of Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Yugoslavia as well as the expansion of Romania in order to prevent the restoration of Austria-Hungary and to counteract German influence in the region. At the same time, these new states were to serve as a cordon sanitaire, keeping Central and Western Europe from being infected by the virus of communism. But these newly drawn borders put about thirty million people into nation-states whose language they did not speak and to which they did not wish to belong. For instance, Italy reclaimed some ethnic compatriots in Istria but also gained a strategic frontier in South Tyrol that was indubitably German-speaking.20

In order to prevent a resumption of the fighting, the losing countries were also thoroughly disarmed, although the victors failed to reduce their own forces in a similar manner. French insistence left the Weimar Republic with an army of only one hundred thousand men without an air force, tanks, heavy artillery, poison gas, or a general staff. While the left bank of the Rhine was occupied, the right bank was also demilitarized. After the crews scuttled sixty-six German warships at Scapa Flow, British pressure permitted only a small coastal-defense navy with fifteen thousand officers and sailors and required all submarines to be handed over. Austria and Hungary were allowed dwarf armies of thirty thousand men respectively. These drastic reductions left the losing countries virtually defenseless and fueled resentment in former military circles, which found themselves suddenly unemployed. Because the new states of Poland and Czechoslovakia were rearming with about half a million soldiers each, this one-sided disarmament created a huge imbalance of forces in the center of Europe. Moreover it sparked constant conflicts over securing its enforcement.21

Perhaps the most contentious issue of the entire treaty system was the question of reparations, since chauvinistic opinion in Britain as well as the rebuilding of France demanded “Germany must pay.” In order to have a legal basis for this claim, John Foster Dulles suggested a statement of German responsibility for the outbreak of the war that became Article 231, the infamous war guilt clause. Complicated by the issue of inter-Allied debts, the Paris debates concentrated on three issues: how to assess the civilian damage caused, how much Germany might be expected to pay, and how the spoils ought to be divided. Adopting a fixed-sum approach, the peacemakers could not agree on an amount and on the number of years, postponing the final decision until 1921. The initially suggested sum of 269 billion gold marks seemed disappointingly low to the vindictive winners and astronomically high to the losers, who would be saddled with payments until 1999. Triggered by John Maynard Keynes’ resignation from the British delegation, the debate about the justice of reparation payments poisoned postwar politics for years.22

The final problem of the Paris Peace Conference was the disposition of Germany’s colonies and Turkey’s provinces, demanded by imperialist interests and British dominions. Justifying the transfer of control by a trumped-up charge of German malfeasance, negotiators made the former colonies “mandates” of the League of Nations, establishing three levels of tutelage, deeply disappointing the anticolonial intellectuals who had hoped for immediate self-determination. While France and Britain split Togo, the Cameroons, and East Africa, Japan received the Chinese port of Tsingtao. South Africa gained Southwest Africa while Australia got New Guinea and New Zealand obtained Samoa. In the Near East the Ottoman provinces were generally turned into new states that were theoretically on their way to independence but practically divided between French dominance in Syria and Lebanon and British preponderance in the rest of the Arabian Peninsula.23 Clashing with Arab aspirations, the 1917 Balfour Declaration that promised “a national home for the Jewish people” in Palestine proved particularly troublesome.24

Judging by their effect on subsequent developments, the Paris treaties remain a flawed system, since they combined innovative Wilsonian impulses with retrograde nationalist clauses. Propelled by a vengeful public and spurred on by militant advisers, Clemenceau and Lloyd George ignored calls for moderation and subverted universal aspirations for the sake of their own national interests. Though he understood that “if we humiliate the German people and drive them too far, we shall destroy all form of government and Bolshevism will take its place,” the U.S. president also wanted to punish Prussian deceit after hearing of the harsh Treaty of Brest-Litovsk.25 The Wilsonian program of domestic democracy, national self-determination, and international cooperation might have provided a constructive order for a postwar Europe, but its modification and one-sided application undercut its credibility. Many concrete difficulties in applying the ideas of the new diplomacy could not have been foreseen. But their halfhearted implementation, at once too harsh to be accepted and too conciliatory to be enforced, ultimately proved to be their undoing.

ADVANCE OF DEMOCRACY

Allied victory provided Europe, nonetheless, with a golden opportunity to choose the liberal vision of modernity by advancing self-government and self-determination within a cooperative international order. While the western Allies felt vindicated, eastern democrats could use the collapse of the multiethnic empires to promote self-rule through drafting republican constitutions. At the same time local nationalists were able to go beyond autonomy and create a series of new nation-states, legitimized by their own rather mythical view of history. Such steps turned ancient social hierarchies upside down, putting the former subjects such as Poles or Czechs on top, since their previous German or Hungarian masters now found themselves as minorities without state support. Yet in order to realize such ambitious aims, the new democracies had to overcome the legacy of underdevelopment, the devastation of war, and the disruptions of the postwar transition.26 Their state-building had to create new governmental structures, ranging from police to military, from postal clerks to tax collectors, and from parliament to diplomacy.

Since Allied propaganda had claimed the Allies were fighting for democracy, the collapse of the autocracies strengthened the appeal of parliamentary government as a superior political system in the West. But the untold sacrifices of the war also induced veterans and suffragettes to claim new political rights as a just reward for proving their citizenship during the conflict. The smaller, neutral democracies such as Switzerland and the Scandinavian countries simply reaffirmed their forms of self-government, somewhat extending participation. In Britain, the Representation of the People Act of 1918 abolished property restrictions, giving all men over twenty-one years the right to vote and enfranchising women over the age of thirty. The French Third Republic already had a broad male franchise, though it took until 1944(!) for women to be granted the vote. At the same time various provisions to help veterans, the wounded, and war widows also started the move toward the modern welfare state. But more far-reaching demands of workers for social reforms or control of factories were generally turned down, preserving the capitalist class system relatively unchanged.27

The dozen new democracies from the Baltic to the Balkans entered the postwar period with high hopes that independence would give their people a better life. No longer would they be lorded over by bureaucrats who spoke a different language; now they could finally govern their own affairs. All of them drafted ambitious constitutions that sought to create nationally minded citizens, ready to participate in the new order. However, reality turned out to be rather sobering. Except for Hungary, all the new states were saddled with minorities that clamored for autonomy, that wanted to belong to a neighboring country or create their own state. The new tariffs that were supposed to shield domestic industry interrupted old trade routes, stifling commerce and economic development. Moreover, the building of national schools, hospitals, and police stations required enormous sums of money that had to be borrowed abroad. As their populations were unused to self-rule, within two decades all the new democracies save Czechoslovakia turned into nationalist authoritarian regimes like Poland under General Józef Piłsudski.28

In defeated Germany, democracy also triumphed as the November Revolution of 1918 overthrew the monarchy. When sailors in the ports of Wilhelmshaven and Kiel heard that they were to embark on a final battle against the British Royal Navy, they mutinied, seeing no point in a heroic gesture at the end of a lost war. Since workers in the factories went out on strike as well, the discredited kaiser was forced to abdicate, fleeing ignominiously by train to Holland. In Berlin, the Spartacists and shop stewards hoped to create a revolutionary regime of workers’ and soldiers’ councils modeled after the Bolshevik example. To forestall such radicalization, the moderate Social Democrat Philipp Scheidemann exclaimed dramatically from the balcony of the royal palace on November 9, 1918: “The old and rotten, the monarchy has collapsed. The new may live. Long live the German Republic!” Outflanking the Council of People’s Deputies, his colleague Friedrich Ebert, the chancellor of the new republican government, eventually restored order in the capital with the help of the army and the support of the business community.29

Stabilizing the embattled Weimar Republic was a difficult but not impossible task. Away from popular passions in the birthplace of German classicism, liberal parliamentarians like Hugo Preuss created an advanced constitution that included proportional representation and gave women the vote. But the cabinet was shocked by the harsh Versailles peace terms, since it had hoped for more generosity from the victors in support of German democracy. On the right, the fledgling republic was besieged by revanchist nationalists who forged a “stab-in-the-back legend,” claiming that the army had been defeated by subversion at home, and rejected democracy as an accomplice of the Allies. On the left, communists and anarchists fomented rebellion in industrial areas, hoping to seize power and install a Soviet-style regime. Moreover, the paramilitary Free Corps roamed the streets, killing Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg while claiming to uphold order and defend the frontiers in the East. Nonetheless, the republic survived its turbulent beginnings, supported by the working class, and eventually gained a measure of grudging respect.30

Democracy faced an equally uncertain future in the new states of Austria and Hungary, which had never before existed in this form. German-speaking Austria found itself with an outsized capital of Vienna, polarized between Christian Social middle-class and Social Democratic working-class parties. The majority of the Austrian parties wanted to join the Weimar Republic, but the Treaty of St. Germain prohibited this obvious solution, as it would have strengthened Germany. Cut off from its prior trading partners through nationalist tariffs, Vienna remained dependent on western loans. Happy to be at last independent, Hungary, however, mourned the loss of about one-third of its ethnic population due to the unfavorable borders drawn by the Treaty of Trianon. A communist rebellion under Béla Kun took over Budapest in 1919, but eventually the Romanian army restored counterrevolutionary order. In January 1920 right-wing forces seized control and allowed Admiral Miklós Horthy to rule as regent for the next two decades. The one-sided application of self-determination thus created two revisionist states, unhappy with the peace.31

The major exception to the sweep of democracy after World War I was the Soviet Union, which promoted itself as an egalitarian alternative to the Wilsonian vision. Lenin never tired of denouncing parliamentary government as a bourgeois sham, while claiming to be protecting civil rights against tsarist persecution. Instead of striving to enlarge political participation in a capitalist system, the Bolsheviks emphasized the need to end economic exploitation in order to obtain social justice as prerequisite for democracy. While this objection to western class hierarchies carried some weight, the Soviets practiced a “dictatorship of the proletariat” after the revolution, claiming that they needed to use force to achieve social change since they were besieged by class enemies. Promoted zealously by the Comintern, the Communist International organization founded in 1919, this rationalization appealed to disenchanted intellectuals and suffering workers in the West who welcomed a critique of capitalist exploitation.32 While it inspired some local uprisings, the communist radicalization of socialism never quite attracted enough support to displace more moderate conceptions of democracy.

The postwar wave of democratization yielded disappointing results, since most new regimes foundered on insufficient preparation and adverse circumstances. In Central and Eastern Europe, an educated minority that had felt shut out in the previous empires seized control of the bureaucracy in the name of self-government, while the agrarian majority merely longed for a better life. The combination of democracy with nationalism incited an endless set of conflicts as the minorities within nations created by the peace fought the efforts of the new governments to enforce linguistic and cultural uniformity.33 The customs borders of a dozen new national states also disrupted trading patterns, and the costs of state-building bankrupted the new regimes. Finally, the weakness of civil society, prevailing intolerance, and lack of democratic habits created a hankering for strong leadership. Born in revolution or defeat, democracy faced enormous hurdles in postwar Europe. At best, the new nation-states responded to desires for self-determination while offering a glimpse of what democracy might become under more favorable auspices in the future.34

TRAVAILS OF THE VICTORS

Even the victorious powers were soon disappointed in democracy, since they found the rewards for their sacrifices inadequate and the postwar transition difficult. The better life that propaganda had promised failed to come, and many of the spoils that secret treaties had envisaged proved unattainable. Moreover, the conversion from a wartime to a peacetime economy turned out to be more time-consuming, costly, and disruptive than imagined. The demand for consumer goods, which had been pent up during the fighting, initially resulted in a buying spree that produced a short-lived postwar boom. But public borrowing to pay for the wartime expenses contributed to a substantial inflation, and once savings were used up the lack of buying power led to a recession when returning veterans struggled to find civilian jobs. Shifting the cost onto the defeated enemies also proved illusory, since reparations payments were smaller than expected and a self-righteous U.S. Congress insisted on the repayment of inter-Allied debts. Within a few months the elation of victory turned into frustration, unleashing domestic strife and blocking international compromise.

Because of its domestic divisions, the constitutional monarchy of Britain experienced an especially trying transition. The Welsh prime minister Lloyd George promised soldiers a land “fit for heroes to live in” during the 1918 khaki election. His coalition of Liberals and Conservatives scored an impressive victory, allowing him to sponsor social reforms such as extending education, providing public housing, increasing the coverage of unemployment insurance, and raising pensions. But in October 1922 the Conservatives, disliking such measures, deserted him, while Labourites agitated for further reforms, replacing the Liberals as the main opposition party during the next election. Their talented but somewhat muddled leader Ramsay Mc-Donald formed the first Labour government in 1924, only to be replaced by his predecessor, the hard-liner Stanley Baldwin, who in turn lost the 1929 election so that McDonald returned with a national-union government in 1931.35 During the interwar years the United Kingdom remained split between a defensive Conservative Party and a reformist Labour Party, with neither strong enough to govern effectively.

Political and social tensions came to a head in the general strike of May 1926. Though British mines had become less productive and the return to the gold standard made coal harder to sell, miners demanded better pay and more services. Appointed by Baldwin to address the problem, the Samuel Commission recommended ending government subsidies and cutting wages for miners by 13.5 percent. Horrified, the unions protested, and, after last-minute compromise attempts failed, the Trades Union Congress (TUC) called a general strike that turned out three million workers, bringing transportation to a standstill. Fearing anarchy, the Conservative cabinet quickly organized emergency services, strikebreakers, and a militia to maintain law and order. When the courts issued injunctions against sympathy strikes of other unions, the TUC called off the general strike after nine days, grudgingly accepting the reduction of wages.36 The confrontation showed that British society was polarized between a laissez-faire-oriented middle class and a growing labor movement, whose radical members were dreaming of a social revolution.

The future of Ireland was a similarly intractable issue, since it provided an inflammatory mix of nationalism, religion, and social resentment. Inspired by sectarian hostility between Protestants and Catholics and aggravated by tensions between absentee landlords and local laborers, the Irish independence movement contested British control over the green isle. In 1914 Charles Stewart Parnell’s agitation succeeded in winning home rule, allowing the formation of Irish volunteers to fight in World War I. But when the radical nationalists rose on Easter of 1916, the British put them down with brutal force, making the Sinn Fein Party’s campaign for independence more popular. A key problem was the future of the six Ulster counties that were dominated by Protestants. In 1921 Lloyd George brokered an Anglo-Irish Treaty that allowed the twenty-six Catholic counties under Eamon de Valera to become independent, retaining Northern Ireland and making the Irish Free State a dominion. While this proved to be a workable compromise, it failed to eliminate the mutual hatred between Ulster Protestants and Catholics that would keep bloodshed continuing for decades.37

Though its reputation was enhanced by victory, France also confronted external dilemmas and internal confusion. The price of glory, with about 1.5 million dead and 3.5 million wounded, had sapped a population of about 40 million, which was only two-thirds the size of Germany’s 62 million. To combat this relative demographic weakness, nationalist hard-liners sought to provide security by enforcing the clauses of the Versailles Treaty to the last letter so as to provide security against a resurgent Germany. In contrast, more flexible leaders of the Left searched for a rapprochement with the Weimar Republic in order to reduce the strain of defense expenditures. Rebuilding the devastated infrastructure, economy, and housing of northern France produced enormous costs that could not all be shifted to the defeated enemies, but tax incentives for reconstruction also created a spurt of industrial modernization. Ironically, even the celebrated reintegration of Alsace-Lorraine proved troublesome, since this partly German-speaking region wanted to maintain some autonomy vis-à-vis the central government, especially in religious affairs.38 The basic challenge confronting Paris was therefore finding a way to preserve the fruits of victory without overextending itself in the process.

The Third Republic failed to come up with a clear solution, since the balance of forces between the nationalist Right and the internationalist Left was roughly equal. Wags claimed that Frenchmen had their revolutionary heart on the left but carried their wallets on the right. Combining various splinter parties, the nationalist hard-liners formed a loose bloc Eational while the reformists created a cartel des gauches. In the parliamentary musical chairs, the tough prime minister Clemenceau, who had pushed for punitive terms at Versailles, was replaced in 1921 by the conciliatory Aristide Briand. But he was ousted a year later by the bellicose Raymond Poincaré since he seemed to have been too soft on Germany. When the latter’s reparations policy proved to be a fiasco, the moderate leftist Eduard Herriot assumed power in 1924, only to be replaced once again by Poincaré in 1926. Since the latter succeeded in resolving a fiscal crisis by devaluing the franc, he governed until 1929.39 This succession of leaders created a zigzag course domestically and internationally that prevented finding a cure for the internal division and structural weakness of the country.

Faced by a dynamic German neighbor, France, weakened by war, struggled hard to preserve its hegemony over the continent. The October Revolution had eliminated Russia as a reliable ally, since bourgeois Paris feared that the Bolshevik virus might spread to its own workers. Moreover, restraint in enforcing the peace was predicated on continuing U.S. involvement and British support, both of which looked increasingly questionable as time went on. To replace these partners, France created a web of alliances with Poland, as well as with the so-called little Entente of Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, and Romania. This ingenious policy proved, however, rather expensive, since these clients required massive subsidies to pay for their domestic development and military strength. Even when France tried to enforce the timely payment of reparations as in the January 1923 occupation of the Ruhr Basin, the intervention backfired. Owing to Berlin’s “passive resistance,” Paris found it impossible to dig coal with bayonets and eventually had to break off the venture. Hence maintaining dominance stretched French resources to the breaking point.40

Instead of offering multiple benefits, victory in the First World War created unexpected new problems for the winning countries. Being victorious reinforced a western sense that liberal modernization was the right path, since democracy had beaten autocracy in the end. Tangible spoils like territorial gains, new colonies, greater military security, and less economic competition were also gratifying. But domestically, victory reaffirmed not only parliamentary government but also capitalist exploitation and class hierarchy, contrary to the claims of veterans for extending the suffrage, providing social reforms, and creating greater equality. While the peace treaties offered a blueprint for a new international order composed of democratic nation-states, they also perpetuated wartime enmities by triggering a protracted conflict over enforcing their provisions.41 The settlement sparked enormous resentment among those who felt disadvantaged by it, precluding its acceptance as a constructive plan for the future of Europe. High hopes therefore soon turned into keen disappointment—even among the victorious states such as Italy.

INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION

Creating a lasting peace entailed not only ending the fighting but also retying the ruptured bonds by creating a modern international order to prevent a recurrence of the carnage. The multiple steps toward reconciliation had to overcome many obstacles. While the American and British occupation troops were quickly withdrawn, the French and Belgians stayed in the Rhineland until 1930. The propaganda apparatus that had vilified the enemy during wartime also had to be dismantled. Though the kaiser was not tried, the “war guilt controversy” continued with mutual accusations for years. Cooperation in international associations had to be restored by readmitting, for instance, delegates of losing countries to scientific organizations dominated by the victors. Finally, the blockade had to be ended and free trade across the frontiers resumed. But economic revival was hampered by conflicts over the suspension of enemy patents and the sequestration of companies, let alone the entire reparations muddle. Undoing the aftereffects of war and resuming friendly exchanges was therefore a lengthy process, hampered as well by the influenza epidemic of 1919.42

The organization that was supposed to solve the problems caused by the peace settlement and enhance international cooperation was the League of Nations. It was founded in 1919 as an intergovernmental structure, headquartered in the neutral Swiss but French-speaking city of Geneva. As an association of sovereign states, it was led by a secretary-general, dominated by an Executive Council of permanent countries and rotating seats, and supported by a General Assembly in which all members had a voice. The work of the Permanent Secretariat was aided by subsidiary institutions that organized cooperation in particular areas such as the Permanent Court of International Justice, the International Labor Organization, the Health Organization, and the Refugees Commission. Aimed at preventing another world war, the Covenant of the League sought “to achieve international peace and security” through open diplomacy, disarmament, and negotiation as well as arbitration. This new institution, the particular brainchild of President Wilson, was a bold attempt to transcend balance-of-power politics through formalizing international cooperation.43

In promoting peace the League had only a limited success, since crucial states did not belong and its decisions were dominated by the victorious powers. The U.S. refusal to join was a serious blow, while the initial exclusion of Germany and Russia failed to represent two of the most problematic powers in its deliberations. Tied to the Versailles Treaty, the League guaranteed the independence of Danzig, supervised the French occupation of the Saar Basin, and provided cover for the reassignment of the colonies through the mandate system. In some conflicts like the disposition of Upper Silesia, it managed to organize plebiscites and determine the ultimate division of the province between Germany and Poland. In minor questions like the border dispute between Greece and Bulgaria in 1925, the League succeeded in mediating between the conflicting parties. But when national interests of big countries were at stake or in minority conflicts within states, the League proved generally helpless, since recalcitrant members could ignore its decisions, confident that these could not be enforced militarily.44

To counteract their exclusion, the outcasts Germany and Russia concluded a friendship treaty in the Italian spa of Rapallo in April 1922. The agreement, negotiated by Foreign Ministers Walther Rathenau and Georgi Chicherin, upset the victors of the war because it showed that the Weimar Republic and Soviet Russia were not entirely dependent on their goodwill. The text of the treaty was innocuous enough, since it merely waived “their claims for compensation for expenditure incurred on account of the war,” in effect mutually canceling German demands for losses due to the October Revolution and Soviet requests for reparations for Berlin’s military occupation. The agreement further promised to restore normal diplomatic relations and to resume economic cooperation, which both countries sorely needed in order to repair the damage from war and revolution. More ominous, however, was the concurrent promise of secret military cooperation, which allowed the Reichswehr to circumvent the disarmament clauses of Versailles and gave the Soviets access to German airplane, tank, and submarine technology.45

The most controversial issue that hindered international cooperation was the question of reparations. When the Reparations Commission set the amount at 269 billion gold marks, the German public was shocked, and even some foreign economists considered the sum excessive. Although Berlin might have been able to pay by raising taxes and lowering the living standards of the German people, the demand put the democratic government on the defensive, so that it dragged its feet regarding in-kind deliveries. The subsequent Ruhr occupation inflamed nationalist passions by increasing the pace of the runaway inflation that undermined the mark while also straining French resources. This deadlock could only be broken by American mediation. Under the leadership of the Republican banker and later U.S. vice president Charles G. Dawes, a compromise was worked out that cut the total amount in half and reduced annual payments to 1 billion marks, rising to 2.5 billion within five years. This sum would be raised by new taxes and U.S. loans. Chaired by Ramsay McDonald, the 1924 London Conference ratified this agreement, thereby ending the stalemate of the Ruhr occupation.46

This solution improved the international climate sufficiently to allow further steps toward cooperation with the Locarno Treaties of 1925. Concluded between German foreign minister Gustav Stresemann, British foreign secretary Austen Chamberlain, and French prime minister Aristide Briand, these nonaggression treaties ratified the western frontiers established at Versailles. At the same time the arbitration agreements with Poland and Czechoslovakia opened the door to peaceful treaty revision in the East. This compromise reassured the western powers of their possessions but also rewarded German “fulfillment policy” with the hope that the eastern losses would not have to be permanent, thereby frightening Poland. The conciliatory “spirit of Locarno” ushered in a period of cooperation between Germany and France that allowed Berlin to enter the League of Nations in 1926. Moreover, it made possible the withdrawal of French and Belgian troops from the Rhineland in 1930 ahead of schedule.47 Though its goodwill proved fleeting, Locarno showed what interwar reconciliation might have achieved, had it been tried more earnestly.

The lessening of tensions in Europe also made it possible to resolve the thorny reparations issue by further scaling down the winners’ demands. Most impartial observers had come to agree that the burden was too onerous for the German government, allowing the Weimar Republic to be attacked by the Right for selling out. In 1929 an international commission headed by the U.S. industrialist Owen Young therefore proposed a plan that reduced the total amount to 115 billion marks, payable in fifty-nine years, with only one-third of the two-billion-marks payments due each year while the rest might be postponed.48 The Wall Street stock-market crash proved even this sum to be unrealistic, leading President Herbert Hoover to proclaim a one-year moratorium in 1930 in the hope that regular payments could later be resumed. But the Great Depression was so destructive that a 1932 conference in Lausanne lowered the amount by another 90 percent, and when raising even this sum seemed impossible, Germany was allowed to default. Only one-eighth of the total was ever paid, with the Federal Republic completing the last installment in 2010!

Though popular passions made reconciliation difficult, the gradual rapprochement in the second half of the 1920s showed that cooperation was possible if it was earnestly attempted. Commemorating the millions of dead and maimed soldiers by constructing war memorials and holding veterans’ parades kept the hatred of former enemies alive. Many problems, like the new borders and ethnic minorities, were intractable under the best of circumstances. Nonetheless, the League of Nations provided a promising forum for international debate and conflict resolution as long as the contending parties were willing to submit to its decisions. The victors gradually realized that making concessions would increase the losers’ desire to abide by the remaining terms of the settlement, while it slowly dawned on the defeated that they might be able to modify some clauses by accepting the rest of the peace treaties. Narrowing this gap of distrust required a drawn-out diplomatic process, supported by positive media coverage. After Locarno such progress seemed within reach, yet it remained fragile when tested by new upheavals.49

LIBERAL RECONSTRUCTION

The Wilsonian program was an innovative effort to create a liberal order for postwar politics that was undermined by incomplete implementation and inherent contradictions. The principle of self-government responded to popular aspirations for greater participation by introducing democratic constitutions. The promise of self-determination reacted to nationalist agitation by suggesting the establishment of nation-states for aspiring ethnic groups. The proposal to organize international cooperation sought to overcome the bellicosity of balance-of-power politics by creating an institution that would render war superfluous. Though appealing, these progressive initiatives would create many new problems. The cultural legacies of authoritarianism could subvert democratic self-government. Mixed ethnic settlements would trigger minority conflicts and border quarrels. Intent on preserving their new sovereignty, independent states might cooperate only when it suited their interests. Though his vision addressed key problems of modernity, Wilson failed to realize its potential destructiveness.50

The spread of democracy to Central and Eastern Europe offered the former subjects of the landed empires an unprecedented chance to determine their own affairs. The overthrow of the tsarist, Habsburg, and Hohenzollern monarchies finally realized the aspirations of the national movements inspired by the ideals of the French Revolution but stymied by the failure of the 1848 revolutions. The tenacity with which the old order defended its control so as to maintain its privileges had allowed only partial progress toward self-government.51 It took the defeat of the authoritarian regimes to create an opportunity for expanding political participation into full representation. In the fierce ideological conflicts after the war, the democratic alternative initially prevailed everywhere except in the authoritarian Hungary and the radical Soviet Union. But many enfranchised citizens were not ready to exercise their newly won rights, since they lacked experience with self-government. The pressures of civil war, economic disruption, and populist nationalism all too quickly turned the new democracies into little dictatorships.52

The creation of a dozen new national states as a result of the Paris peace treaties was also a great advance for self-determination by allowing different ethnicities to govern themselves. From the Baltic to the Black Sea, former subjects of Russian, German, and Hungarian rulers were now free to form their own national states in which they could realize their dreams of independence. This liberation from previous masters meant being able to use their own language in public affairs, teaching their children their cultural heritage in schools, and receiving international respect like older established nations. But the minority safeguards of the League of Nations were inadequate to cope with the ethnic mixture in East-Central Europe, in which Germans, Jews, and Slavs lived together in cities like Prague. Nationality censuses became ethnic battlegrounds, since claims to power or borders depended on the identification of citizens with a specific language. The one-sided implementation of self-determination to weaken the Central Powers and the exclusion of Soviet Russia also created fierce disputes that would later lead to ethnic cleansing.53

The establishment of an international organization in order to mediate conflicts and avoid another world war also seemed to be an excellent idea. In effect, the foundation of the League of Nations took up the legacy of the Congress System in a more formal and liberal fashion a century later. Creating a forum for international public opinion to discuss the world’s problems, reinforcing legal guidelines for the intercourse between nations, and addressing specific issues such as the protection of labor were honorable goals that would lessen tensions between countries. But defenders of national sovereignty managed to subvert the initiative by insisting on the veto right of the great powers, excluding the defeated enemies and the Soviet Union, keeping the United States from joining, and tying the League to enforcement of the controversial peace treaties. While the League did manage to settle a series of border conflicts through plebiscites and succeeded in civilizing international debates, it failed disastrously in dealing with those disputes between the major powers that would unleash another world war.54

The effort at democratic modernization at the end of the First World War proved therefore at once attractive and disappointing. The defeat of the Central Powers created a historic chance for building a peace on the principles of democracy, self-determination, and international organization. Because of these attractive ideas most citizens in Central and Eastern Europe chose Wilson’s liberal program of reform over Lenin’s communist promise of revolution. But nationalist fervor and conservative opposition among the victorious Allies made the implementation of these ideals in the Paris peace treaties rather one-sided, favoring the victors in virtually every disputed case and thereby fanning lasting resentment among the losers. Moreover, the inherent difficulties of creating self-government in countries not quite ready for it, establishing national states in mixed ethnic areas, and founding an international organization without ceding sovereignty limited liberal modernity to the West. The Wilsonian vision continued to inspire democrats thereafter, but it would require further improvements in order to prevail in the end.55