DEVASTATING DEPRESSION

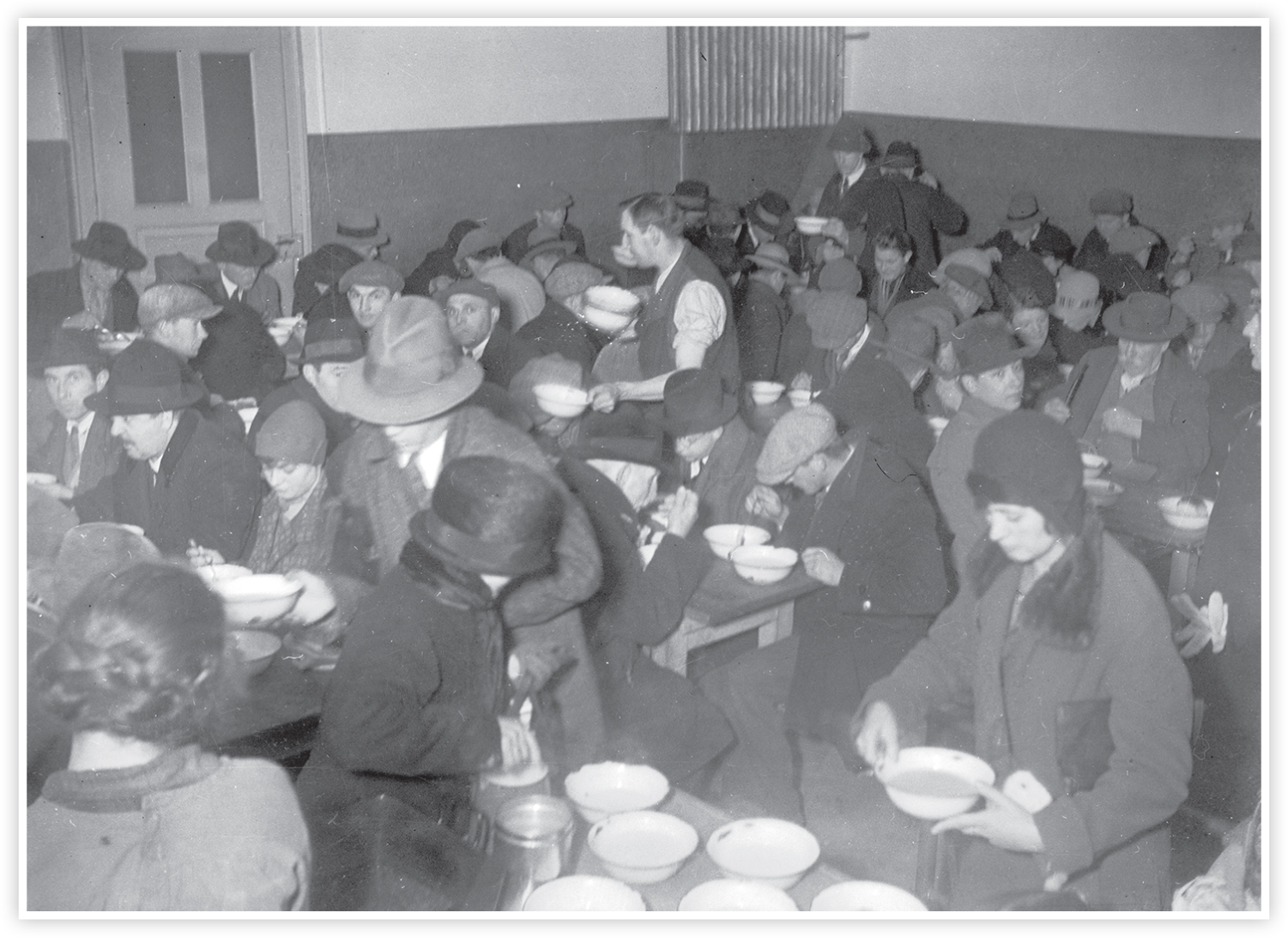

Depression soup kitchen, 1930. Source: bpk, Berlin / Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich / Art Resource, NY.

On May 11, 1931, the Creditanstalt informed the Austrian government that it was bankrupt, setting off a run on its deposits. The biggest Viennese bank could no longer meet its obligations, because it had taken on too much debt by swallowing a competitor two years earlier and French depositors were withdrawing their assets in order to keep Austria from joining a customs union with Germany. Though the City of London offered a fresh loan, the Viennese government collapsed, and the panic spread to smaller institutions, making one banker shoot himself and another try to jump into the Danube. A month later when rumors claimed that one of its key debtors, the textile company Nordwolle, had become insolvent, the Darmstädter Nationalbank also came under pressure, triggering another run in Germany, the biggest continental economy. On July 13 the Berlin government saw itself forced to declare a bank holiday, stopping all financial transactions for two days.1 Almost two years after Black Thursday, the stock-market crash in New York, these bank failures brought the financial crisis to Europe with a vengeance.

The banking collapse turned a cyclical economic contraction into a larger and longer downturn that worried observers like President Herbert Hoover called “the Great Depression.” As a result of wartime overproduction, agricultural and raw-material prices had already fallen by roughly one-third during the previous decade. But after Black Thursday, the major lenders in New York and London stopped issuing credit and started to recall their short-term loans from Europe, forcing $2 billion to flow out of Germany during six weeks in the summer of 1931 alone! In the worsening business climate, coal and steel production dropped by 40–60 percent, and world industrial output shrank by 30 percent. European trade fell from $58 billion to $21 billion between 1929 and 1935. As a result, more than twenty million Europeans became unemployed.2 The linkage among financial, agricultural, industrial, and trade losses amplified a normal recession into a depression of a length and magnitude that had previously seemed unimaginable. Caught unprepared, governments were at a loss as to how to break its devastating grip.

The question of how to respond to the Great Depression sparked a fierce ideological debate between monetarists and Keynesians that still dominates economic explanations. On the one hand, the central bankers, led by Sir Montagu Norman of the United Kingdom, insisted on defending the gold standard as a guarantee of fixed exchange rates in order to facilitate international trade. The American financier Andrew Mellon considered the depression to be an economic punishment for the excessive speculation of the 1920s, advising Wall Street to “purge the rottenness out of the system,” that is, let the overextended speculators fail rather than try to rescue them through government intervention. On the other hand, British economist John Maynard Keynes, supported by the trade unions, argued for countercyclical government spending in order to restart the economy. During recessions, he argued, it was necessary for governments to borrow money and undertake public projects to put people back to work, providing buying power that would revive business by increasing demand. Convinced that “this time is different,” neoliberal economists continue to blame the Federal Reserve for failing to limit the money supply, while left-wing commentators criticize the “gold standard mentality” as cause of the deflationary policies of the national governments.3

More than any other interwar event, the Great Depression turned European development from peaceful optimism into bellicose pessimism by halting the material progress of modernity. The practical impact on the millions of unemployed was severe, because they had to struggle for their very survival at a time when public assistance was cut back. The psychological effect on their more fortunate neighbors was equally unsettling, since these had their salaries cut and feared losing their jobs, living standards, and security. A whole generation of high school and university graduates, who seemed to have no future due to the loss of jobs and lack of hiring, blamed “the system” for a plight for which they did not feel responsible. With no end of the downturn in sight and international cooperation collapsing, many commentators began to ask, with Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter: “Can capitalism survive?”4 Because the Soviet Union made great strides in industrialization during the Great Depression and even Fascist Italy seemed to escape its worst effects, the slump triggered a crisis for the democratic path of modernization.

By reversing the trajectory of material progress, the Great Depression reinforced those negative aspects of modernity that brought Europe to the brink of self-destruction in the subsequent decades. The difficulties of economic adjustment after the First World War and the effects of hyperinflation delayed the postwar recovery and limited the return of prosperity to merely half a decade. The depth of the subsequent disruption caused by the bank failures disappointed hopes in the resumption of progress, creating a climate of fear in which individuals, companies, and countries scrambled to survive by following their immediate self-interest: reducing consumption, production, and international commerce in a self-reinforcing downward spiral. Massive unemployment increased tensions between the social classes, since the unions clamored for public assistance while the struggling business community refused to help. The disruption of international trade and credit strengthened an economic nationalism that prevented cooperation and encouraged autarchy. Making the leftist and rightist dictatorships appear more dynamic and effective, the liberals’ refusal to engage in public works discredited democracy, setting Europe on a disastrous course.5

POSTWAR DISRUPTION

Already during the Versailles negotiations in 1918 John Maynard Keynes, as adviser to the British delegation, warned that the consequences of a harsh peace would be disastrous. While he criticized the terms as generally unfair and in violation of the prearmistice agreement, the brilliant Cambridge economist was especially concerned about the demand for large reparations, cautioning against their inflationary effect. Moreover, he also called for a cancellation of inter-Allied debts as an American contribution to a war that Washington had joined only in April 1917. While Keynes, as a disappointed Wilsonian, may have been unrealistic about what was possible in the heated postwar atmosphere, he was on the mark with his criticism of the economic results of Versailles. “But who can say how much is endurable, or in what direction men will seek at last to escape from their misfortunes?”6 With about one-quarter of its gross domestic product destroyed, continental Europe needed a plan for economic recovery and international cooperation rather than the creation of divisive borders and high expenditures for military security.

Repairing the appalling physical destruction was a daunting task in itself. The battlefields ranged from northern France, Belgium, and northern Italy to Poland, Russia, and the Balkans, not to mention the Near East and the colonies. The trench systems, artillery barrages, and air bombardment of modern warfare had created a moonscape full of shell craters, waterlogged ditches, felled trees, destroyed buildings, and human as well as animal cadavers. Reclaiming the land for planting and rebuilding the houses for living was a major challenge. In France alone 23,000 factories, 5,000 kilometers of railroads, 200 mine shafts, 742,000 houses, and 3.3 million hectares of farmland had to be reconstructed at a cost of 80 billion francs.7 While the richer countries of the West could finance such a public effort, in the East and the Southeast newly created states like Poland and Yugoslavia had few resources and capabilities for meeting this difficult challenge. Even if the reconstruction created temporary jobs, the expenditure required to return standards of living to prewar levels was enormous.

Including both military casualties and deaths from indirect warfare against civilians, the demographic losses were also severe—and largely irreparable, since the dead could no longer sire children. Most estimates suggest that between 9.4 and 11 million soldiers and 7 million civilians perished during the First World War, while almost twice that number were mutilated by wounds. Germany alone lost 2,037,000 men, Russia another 1,811,000, France 1,398,000, Austria-Hungary 1,100,000, Britain 733,000, and Italy 651,000. This carnage cost France and Germany about 10 percent of their workforce, Italy and Austria-Hungary 6 percent, and the United Kingdom 5 percent. Moreover, the neglect and destruction of crops and the naval blockades caused widespread starvation, which the Quaker Herbert Hoover and the American Relief Administration sought to alleviate by shipping millions of tons of grain to war-torn Europe. Finally, the influenza pandemic of 1918 claimed millions of additional lives in a population weakened by fighting and famine.8 In demographic terms, the First World War caused a deep, permanent gash on the male side of the European population tree that hindered the recovery.

The economic warfare and the creation of new states also redirected and disrupted international trade. The war itself reshaped exchange patterns, interrupting continental business while enriching the neutrals and overseas countries. The peace treaties made things worse by carving up the German, Austro-Hungarian, Russian, and Ottoman empires and increasing the number of European countries from twenty-four to thirty-eight, which used twenty-seven different currencies. Intent on asserting their sovereignty and on incorporating their newly won territories, these East-Central European and Balkan states hardened their borders by levying tariffs in order to raise revenue. Such custom barriers interrupted ancient trade routes, while much of the lending sought to shore up diplomatic alliances rather than following standards of profitability. President Wilson’s hope for free trade was therefore quickly dashed by the increasing barriers of economic nationalism. As a result world trade had sunk to 53 percent of the prewar level in 1921 and did not recover to the pre-1914 amount until the end of the decade.9

These structural problems were aggravated by interminable political wrangling over reparations and inter-Allied war debts, which complicated loans for recovery. In the heated postwar atmosphere, the Reparations Commission found it impossible to determine scientifically how large the actual damages were and what Germany could realistically be expected to pay. The sum of 132 billion gold marks determined at Spa in 1920 seemed too large to Berlin, while the actual annual payments of about one billion pounds appeared too small to Paris. At the same time the U.S. government was unwilling to forgive its loans to the Entente countries for the purchase of war matériel that had fueled a boom in the United States, though these could have been considered a financial contribution to the struggle. The refusal to recognize a linkage between reparations and war debts created a circular bind: though their economy was recovering, the defeated Germans did not want to pay reparations, which the victorious European Allies needed for repaying their U.S. debts.10 Because of this deadlock, the reparations quarrel blighted prospects for full recovery.

The wartime damage was so severe and long lasting that it ended the European dominance of the world economy. Already during the First World War military conscription, the requisitioning of horses, the use of fertilizer as gunpowder, and the destruction of land shifted agricultural production to the wheat fields of Canada and the cattle ranches of the American West. At the same time the Entente’s need to procure war matériel transferred financial leadership from London to New York, making the unprepared United States “the world’s banker” and requiring it to play a crucial role in European recovery. Although the continent reclaimed its productive capacity after the end of the carnage, the European share of world trade fell from 36 percent in 1914 to 24.4 percent in 1936. The nationalist preoccupations of the peacemakers largely ignored the economic dimension in drawing up boundaries and insisting on reparations and inter-Allied debt payments that poisoned the international climate. Europe lost almost a decade in growth, hastening its decline when compared to the booming United States and the rising Soviet Union.11

The war and its aftermath also interrupted the spread of globalization, which had linked European countries and the rest of the world more closely at the turn of the century. In almost all indexes of production or trade, the First World War created a jagged drop, breaking the line of long-range progress. After the war the curves once again moved in an upward direction, but they started from a lower beginning point and only reached prewar levels during the late 1920s, lagging behind where they would have been if peace had continued. The gradual pacification of the continent and the return of the gold standard did help reenergize international exchanges. But the wartime distortion and the postwar rebuilding changed the perspective from free trade to protectionism, since each country was preoccupied with rebuilding its economic base and getting ahead as quickly as possible. By weakening the links of finance and commerce between the advanced countries, the wartime exertions and difficult transition to peace interrupted the momentum of economic progress, which had hitherto made modernization appear in a positive light.12

The postwar disruption of European economies was compounded by inflationary pressures that eroded the buying power of the major currencies. Having lost only half the value of the pound by the end of the war, Great Britain was better off than its neighbors, whose purchasing power declined three- or fourfold. Since much financing of the war had come through public borrowing in the hope of shifting the cost to the losers, governments were tempted to run their currency-printing presses so as to retire the bonds at lower cost. The returning veterans also demanded social services for their wounded comrades, and for war widows and orphans, as well as unemployment assistance as long as they were searching for work. With conversion from war production to peacetime consumption taking some time, the pent-up demand, delayed building, and reconstruction fueled a short-lived boom, which chased a limited amount of goods, allowing producers and shopkeepers to raise their prices.13 Since wage adjustments rarely kept up, inflation seemed a relatively painless way to lower living standards—as long as it could somehow be kept under control.

But in Germany, Austria, Hungary, Poland, and Italy, the bankers failed to curb the rise in prices, allowing a hyperinflation to develop, which not just depreciated but actually destroyed the currency. The most dramatic example was the reichsmark’s loss of purchasing power, which accelerated geometrically from 1913:

| 1918 | 245% |

| 1920 | 1,400% |

| 1921 | 3,500% |

| 1922 | 147,000% |

| 1923 | 126,000,000,000% |

The printing presses could hardly keep up with the production of new bills containing ever more zeroes when prices first rose monthly, then daily, and in the end even hourly. People had to go shopping immediately after getting paid, since their wages would have lost too much of their buying power by the end of the day. Handling the money got so unwieldy that distraught Germans used backpacks and even wheelbarrows to take the inflated paper to the stores. This runaway inflation also destroyed the convertibility of the currency, since by the fall of 1923 it took four billion reichsmark to purchase merely one dollar!14

The hyperinflation had a drastic, albeit contradictory, effect on society. On the one hand, debtors profited, because it practically wiped the slate clean when they could repay their loans with depreciated currency. Moreover, for people with tangible assets such as factories, stores, houses, or land it was a boon, since their values were not affected by price rises. But on the other hand, citizens who had lent money or invested in the stock market took a loss, because their paper holdings increasingly became worthless. Moreover, everyone on fixed income like rentiers, pensioners, or public officials suffered grievously, since the buying power of their remittances rapidly evaporated and salaries were only slowly adjusted, falling ever more behind the steep rise in prices. Even if some individuals who managed to turn their assets into dollars grew richer, wide circles of the middle class lost confidence in an economic system that cheated them out of their life savings and eroded their current earnings.15 No wonder voters flocked to extremist parties that promised to restore economic security.

This German inflation spiraled completely out of control through the struggle over reparations, which led to the French occupation of the Ruhr Basin. When Berlin fell behind with the delivery of 135,000 telephone poles and 2.1 million tons of coal, the hard-line Parisian premier Raymond Poincaré decided on January 11, 1923, to send troops into this industrial region, seizing “productive pledges” to assure future compliance with reparations. Fearing French separatist designs on the Rhineland, the Berlin cabinet proclaimed a policy of “passive resistance,” consisting of labor strikes, bureaucratic noncooperation, and occasional acts of sabotage. The occupiers created a mine administration company (MICUM) that extracted coal from belowground by forced labor, killing over 130 people in retaliation. In order to keep up the resistance, the German government paid the lost wages to the strikers, further running the printing presses and accelerating the devaluation of the reichsmark.16 Neither side wanted to back down, because the Ruhr struggle was a symbolic contest about observance of the peace treaty.

It took U.S. mediation with the Dawes Plan to break the deadlock and return Europe to the road toward stability. Only gradually did Washington realize that its financial stakes on the continent required an active policy of mediation in order to revive its largest market. Moreover, the French leaders slowly understood that a punitive policy toward their neighbor overstrained their resources, imperiling their own currency. Finally, the Berlin cabinet under Gustav Stresemann also recognized that nationalist posturing was futile, called off the passive resistance, and issued a new currency, the rentenmark, which would be backed by the productive assets of the country. Owing to Anglo-American pressure to treat Germany more fairly, the London Conference worked out a compromise in April 1924, named after the U.S. banker Charles G. Dawes: in exchange for a gradual withdrawal of French troops, Germany promised to pay 1 billion marks during the first year, rising to 2.5 billion annually thereafter.17 Only the experience of hyperinflation convinced Paris and Berlin that treaty fulfillment would have to be tied to a partial revision of the terms.

Five years after the end of the war the reparations settlement finally stabilized the European financial system, albeit at considerable cost. With the Gold Standard Act of May 1925 Great Britain returned to prewar parity, as Chancellor of the Exchequer Winston Churchill claimed, in order to “facilitate the revival of international trade” and restore its “central position in the financial systems of the world.” France and several dozen other countries followed suit, reviving economic confidence and facilitating American loans. Yet the price of stabilization was high, since the return to the gold standard overvalued the British, French, and other currencies by 10–20 percent, making their goods less competitive.18 Moreover, the cost of the war, the ensuing disruption, and the hyperinflation had impoverished wide circles of Europeans previously living on capital, receiving fixed pensions, or dependent on public salaries. The psychological legacy of the postwar difficulties was a deep-seated fear of inflation and a hardening of laissez-faire orthodoxy that would make future crises more difficult to resolve.

FLEETING PROSPERITY

In Europe the “golden twenties” were limited to the half decade between 1924 and 1929, when a brighter future seemed to be dawning at last. Driven by new industries such as chemicals, electronics, cars, and airplanes, production indexes rose by about one-quarter, while international trade actually returned close to prewar levels. Though still higher than before, unemployment generally declined, allowing more workers to share the fruits of the recovery. With increasing tax receipts, national governments could undertake welfare measures such as extending unemployment insurance, while municipal administrations embarked on public housing and transportation projects. Intent on making housekeeping easier, women could buy new products such as electrical stoves, vacuum cleaners, and refrigerators. In the fast-paced metropolitan centers, a quest for romance drove flappers into dance halls to meet young men in search of diversion. The pleasure seeking memorialized in the musical Cabaret suggests that the second half of the 1920s was an exciting time, when people assumed that progress had resumed.19

Much of the expansion was based on American loans, which provided credit for rebuilding European industries. From 1899 on the United States had experienced a spectacular period of growth due to its mastery of mass production and only peripheral involvement in the First World War. A good part of the available capital was looking for investment opportunities abroad, where yields would be higher than at home. With the return to the gold standard, Europe appeared to be a safe enough bet, especially since its bankers shared the same laissez-faire philosophy. From 1925 to 1929 about 5.1 billion dollars were invested in the Old Continent, over half of it in Germany. Most of the money went into modernizing industries under pressure to generate enough tax revenue for financing reparations payments to the victors, but some of it disappeared in municipal improvements. Moreover, many loans were short term and used to refinance older debts that had come due—thereby creating a revolving door of credit that kept spinning only as long as new funds flowed in.20

Another problem was the fall in raw-material and agricultural prices that cut their average values in half by 1930. By expanding exploration and mining, the enormous demand for war matériel during the Great War had increased the output of raw materials, driving down their prices once the military demand vanished. At the same time the need for food encouraged an increase in the output of wheat and beef in the United States, Canada, Argentina, and Australia. which flooded the postwar market, while European farmers struggled to resume their own production. The result was a glut that depressed prices, helping urban consumers by lowering their food costs. But in rural areas like Schleswig-Holstein the surplus also created a severe agricultural crisis, spawning radical populist movements that demanded protection from cheaper foreign competition. Governments responded with drastic increases in tariff levels for foodstuffs so as to shield their domestic producers.21 While the fall of raw-material and food prices favored industrialists and consumers, it also reduced the ability of a significant part of the population to buy manufactured goods.

Industrial output did grow substantially in the second half of the 1920s, but European expansion remained sluggish and uneven when compared to the concurrent upsurge in the United States. Many older factories were hampered by their obsolete equipment, with little incentive to invest as long as the overseas colonies or the creation of cartels provided a secure market. Of course, there were also dynamic new industries like automobile manufacturing, in which some giants like Renault, Austin, and Opel catered to the middle class while luxury car makers such as Jaguar, Ferrari, and Mercedes appealed to the elite. But motorization during the 1920s remained limited to less than one-fifth of the population because of its high cost. Moreover, industrialists also had to contend with a stronger labor movement that used strikes to force such concessions as the forty-eight-hour week and increases in wages. For European industry the twenties offered opportunities for conversion back to peacetime production and expansion into new product lines, while at same time accelerating the loss of its world-leading role to the United States.22

Competing with the more dynamic American economy required the introduction of the gospel of “industrial efficiency” into European business. Only by copying Henry Ford’s innovation of the assembly line could continental manufacturers hope to produce their cars as cheaply as the subsidiaries of the Ford Motor company in Europe. Searching for profit, many industrialists also embraced the time-and-motion studies of Taylorism, which promised a “scientific management” of large companies by cutting out redundancies and waste. Interested businessmen and engineers like Ferdinand Porsche therefore visited the United States in order to see with their own eyes what they could do in order to advance the “rationalization” of their companies. For the blue- and white-collar workers involved, such “Americanization” usually meant being dismissed from their job and becoming unemployed even during the best period of recovery.23 While rationalizing efforts made production more efficient, such measures also created a widespread sense of insecurity, since it was not clear who might be the next to lose his job.

Many of the loans also went into reforming municipal infrastructure, resuming prewar aspirations to make urban centers more livable. Such efforts involved extending the public-transportation network by adding more subways, rapid-transit trains, tramways, and bus routes in order to satisfy the rising demand for mobility. The British “garden-city” movement of Ebenezer Howard inspired continental attempts to provide cheap housing in a parklike setting, allowing tired workers to escape their noxious slums. A curious combination of life reformers, artists, and trade-union members promoted such “greenbelt” projects in the hope that planned cooperatives could strengthen the sense of community and provide a healthier lifestyle than overcrowded tenements.24 Local governments therefore created parks, built swimming pools, and constructed schools in order to counteract the negative effects of urbanization. While these laudable attempts generated jobs and improved the quality of life for people with modest means, they also required considerable public borrowing that would one day have to be repaid.

During the second half of the 1920s many Europeans grew hopeful that they might have overcome their war-related troubles and resumed the prior progress toward a beneficent modernity. In contrast to the previous disruptions, the visible signs of recovery gave ordinary citizens a sense that “normalcy” was returning, which would allow them to get on with their private lives. As a result of the rise in wages, consumers became more confident and willing to buy from grand department stores like Harrods in London, Galleries Lafayette in Paris, and the Kaufhaus des Westens in Berlin. With more money in their pocket, Europeans could eat better, purchase new consumer goods like cameras, and afford entertainment such as movies. And because of their reduced working hours, they could also go on vacations farther away from home. Advertisements in glossy magazines catered to these emerging tastes, while movie stars and sports heroes presented role models for a better life. It is this glittering surface of urban leisure that has become enshrined in the popular memory as the “golden twenties.”25

The fleeting return of prosperity, however, failed to address the underlying structural problems that weakened the European economies in international and social terms. On the one hand, the expansion was largely built on American lending, which began to dry up in the second half of 1928, already bringing the German economy to the brink of a recession. On the other hand, by the 1920s industrialists had figured out how to organize mass production efficiently, churning out an ever greater number of consumer goods. But the continuing inequality in the distribution of income made it impossible for the laboring masses to buy enough of these products, creating a severe problem of underconsumption. While the rise in wages and the gradual extension of unemployment insurance increased demand somewhat, such measures were insufficient to absorb all the new consumer goods.26 In spite of such unresolved problems, optimism was widespread that the “politics of prosperity” would continue, resuming at last the prewar advance of progress, which would realize the promise of modernity.

Such optimism notwithstanding, the U.S. stock-market crash on October 29, 1929, initiated a severe downturn in Europe, which surpassed the normal recessions of the business cycle in depth and duration. Already declining because of the Federal Reserve’s tightening of credit, on the “most devastating day in the history of the New York stock market” shares plunged downward by 11 percent, altogether losing 40 percent of their nominal value by mid-November. Once the drastic drop began, panicked investors started selling their stocks, since they had speculated on margin that the upward direction would continue. Now frantically trying to avoid losing not just their recent gains but their original capital, they hurried to divest themselves of their holdings, thereby accelerating the market collapse. From a high of 381.17 points on September 3, 1929, the Dow Jones average fell to a low of 41.22 by July 1932—an unprecedented decline of almost 90 percent! While French bankers smirked that this was an overdue lancing of an abscess, the stock-market crash destroyed continental business confidence, since New York had become the financial capital of the world.27

The bursting of the speculative bubble created an international financial crisis by inducing U.S. investors to recall their short-term loans to European governments and businesses. Having overextended credit to stock-market speculators, American banks themselves began to fail, with 1,300 going under in 1930 and another 2,300 closing their doors in 1931. In order to shore up their own balances, U.S. financiers recalled $4 billion from Germany and another $1.3 billion from Austria in the months after the stock-market crash. These precipitous capital outflows transmitted the banking crisis to Europe, contributing to the failure of the Creditanstalt and the Danatbank in the summer of 1931. It did not help that the German government tried to use the financial troubles to end reparations, while France insisted on observing the letter of the Dawes Plan and the British sought to defend the gold standard of the pound. The disagreement among continental leaders led to a standstill agreement regarding German loans, halting debt service.28 Since international lending dried up, the transatlantic circulation of capital stopped.

The deflationary effect of misguided monetarist policies turned a cyclical recession into an unprecedented depression. According to the liberal orthodoxy of laissez-faire, dominant in the City of London, governments were supposed to stay out of the economy while the maintenance of the gold standard required balanced budgets. Since the contraction of business lowered tax receipts, most politicians thought they had no choice but to lower expenditures, canceling projects and reducing social services, just when they were most needed. In Germany the Brüning government therefore embarked on a drastic “austerity policy” that cut the salaries of public employees by as much as 30 percent, dismissed officials, and froze hiring of replacements in order to reduce the payroll. Looking to defend their own farms and factories, many states raised tariffs, instituted import quotas, and resorted to currency controls, thereby hampering international trade. The German cuts in expenditure, the British defense of the gold standard, and the French insistence on balanced budgets deepened the downturn, creating a vicious cycle, spinning downward at an ever greater pace.29

In the deteriorating economic climate businessmen lost confidence and started to retrench, thereby further aggravating the crisis. When loans dried up, new investment came to a complete halt. Declining sales forced companies to reduce their own costs, forcing them to take additional rationalization measures and lay off nonessential workers. While the one-fifth drop in wholesale prices also lowered the cost of foodstuffs and raw materials, the evaporation of business profits demanded shutting down all peripheral activities that did not pay for themselves. Owing to the pressure on their own balance sheets, companies started to recall outstanding debts, jeopardizing the survival of firms that were unable to meet their obligations. No doubt some branches that produced consumables were less affected, since customers had to continue eating and wearing clothes, but whole industries like car making, steel production, and shipbuilding were in dire straits. In the windows of marginal shops, “going out of business” signs multiplied, while mismanaged larger enterprises went bankrupt at an alarming rate.30

The ensuing collapse of industrial production reached astounding proportions, especially in those countries that were most heavily industrialized and involved in international trade. Compared with the 1929 figures, by 1932 industry output was virtually cut in half in the United States (53 percent), Germany (53 percent), and the smaller states of Central Europe like the Netherlands (47 percent), Austria, and Czechoslovakia, whose economies were closely intertwined. Less affected were France (72 percent) and Belgium, which formed a “gold bloc,” as well as Britain (84 percent) due to its preferential commonwealth trade and devaluation of the pound. Other countries that managed to isolate themselves, such as the Swedish welfare state and the militarized Japanese economy (98 percent), were hardly affected at all. Finally, Soviet Russia, in the midst of its first Five Year Plan, actually experienced an impressive growth spurt (183 percent) while capitalist states suffered.31 Where the depression hit hardest, economic activity almost ground to a halt.

Government cutbacks and business layoffs produced an unprecedented amount of unemployment that overstrained the still-limited welfare systems. While figures understate the true extent, since they measure only the registered jobless, they indicate a drastic situation: In Germany, the hardest hit, the number of unemployed rose from about 1 million in 1927 to 6.12 million in 1932, in contrast to only 12 million people who were still employed. Among the neighboring countries the situation was hardly better, and even in Great Britain 3.75 million workers were out of a job in 1933. These numbers do not even include the underemployed, on short hours, who were just barely hanging on. About half of the labor force was therefore in dire straits. Unemployment hit especially the industrial areas; the young, who found no jobs; women, who lost their service positions; and the old, who were forced to retire before their time. In the Weimar Republic as many as 2.03 million workers were dependent on welfare support, while religious relief efforts and private charities were unable to care effectively for the rest.32

According to contemporary studies like Paul Lazarsfeld’s investigation of Marienthal, the effect of unemployment was the progressive destitution of the bottom third of the population. Indebted farmers who could no longer make a living because of falling agricultural prices were forced to sell their meager holdings and become landless laborers. Jobless industrial workers quickly spent their savings and desperately tried to grow some food or tobacco in urban garden plots (Schrebergärten) where available. While the more fortunate would be fed in soup kitchens, others were even reduced to begging when municipal relief efforts failed. With all resources devoted to procuring nourishment for bare survival, clothing deteriorated visibly, and health care had to be neglected. Even if outright starvation was relatively rare, public-health doctors found that especially children were seriously undernourished. No wonder vagrancy and suicides increased everywhere.33 Such early sociological investigations sought to galvanize the public to offer more effective help.

By dramatizing the demoralizing effects induced by the Great Depression, writers also sought to arouse sympathy. In Germany the journalist Hans Fallada wrote a bestseller in 1932 with the apt title Little Man, What Now? In simple everyday language he described the social descent of a lower-middle-class salesclerk who was fired from his job in a clothing store and could no longer support his wife and small child. Since many readers could imagine the experience of a loving couple struggling against hopelessness, the book became popular although it failed to offer a way out of the predicament. In contrast, the British writer George Orwell five years later offered both a documentation of the suffering of Lancaster miners and a spirited appeal for socialism in The Road to Wigan Pier. The first part of the volume was a graphic description of the terrible effects of unemployment on the families of coal miners, living in abject poverty, while the second section attacked middle-class complacency. Distributed by the New Left Book Club, Orwell’s message argued that only socialism could end the widespread destitution.34

These reports described the psychological impact on the unemployed workers as devastating. By being thrown out of their job, they lost not only lost their income, status, and security but also their self-respect and manhood when they could no longer provide for their families. Since personal identity was defined by a person’s work, being deprived of this essential marker had a demoralizing effect. Most unemployed went through a sequence of stages, starting with initial unconcern about finding another job, progressing to impotent anger against the injustice of being fired, leading to frantic activity to find another position, but ending after repeated failures in fatalistic apathy. While they were even more at risk, women became more powerful in the family, as it was their ingenuity and parsimony that kept everyone alive. Most jobless workers blamed employers for sacking them and criticized the government for not helping effectively. Not finding another job and living on the dole created passivity. As one jobless man put it, “These last few years, since I’ve been out of the mills, I don’t seem able to take trouble somehow. I’ve got no spirit for anything.”35

Since appeals to charity as well as trade-union initiatives failed to alleviate the suffering, the unemployed could only protest, demanding direct material aid and insisting on a reversal of deflationary policies. With millions of the jobless available as scabs, labor unions hardly dared to strike. Distressed workers therefore appealed to the public authorities of Manchester in May 1932: “We tell you that hundreds of thousands of the people whose interest you were elected to care for are in desperate straits. We tell you that men, women and children are going hungry. We tell you that great numbers of your fellow citizens, as good as you, as worthy as the best of us, and as industrious as any of us, have been and are being reduced to utter destitution.” The petition went on to warn of the dire consequences and demand a change of policy: “We tell you that unemployment is setting up a dreadful rot amongst the most industrious people in the body politic. We tell you that great measures of relief are needed and that it is absolutely essential … to provide a vast amount of public work.”36 The labor movement called for public expenditures to alleviate the symptoms of the depression and social reforms to eliminate its causes.

One consequence of the insecurity and suffering was a decided radicalization of European politics. To begin with, many afflicted citizens considered capitalism itself to be the culprit, because they believed that greedy speculation and heartless profit seeking had triggered the Great Depression. If an unemployed worker realized after months of seeking another job that “there was nothing to be had” in spite of his best efforts, it was logical for him to conclude that something more fundamental must be wrong with the system. Moreover, the deflationary policies and inadequate relief measures discredited democratic governments, which proved incapable of stopping the downturn and were incompetent in alleviating its pain. Older men therefore began to doubt their longtime political affiliations, dropping their memberships in parties and trade unions. Feeling shut out from the workforce, the young increasingly listened to the radical slogans of the communists or the fascists, who strove to abolish both capitalism and democracy.37 Even in established parliamentary states, the Great Depression raised doubt about the survival of democracy.

The inability of parliamentary governments to end the depression provided critics from the Left and the Right with ample opportunity to denounce democracy as incompetent. Leftist intellectuals like the writer Kurt Tucholsky satirized the insensitivity of military and moneyed elites to proletarian suffering and looked for revolutionary solutions to economic problems. Waged in the name of humanitarian values, this attack on popular self-government proved difficult to refute. Rightist thinkers like jurist Carl Schmitt, who considered politics a form of muted civil war, ridiculed the ineffectiveness of parliamentary debate and pronounced “mass democracy” unfeasible. Such neoconservative theorizing also claimed to act for the people in striving for a more forceful and authoritarian form of government. Against such widespread denunciations, defenders of democracy like the legal theorist Hans Kelsen had a difficult time justifying the slowness of public deliberation and the difficulty of finding compromises.38 By discrediting liberalism, the depression reinforced the drift toward dictatorial versions of modernity.

UNEVEN RECOVERY

Recovery from the depression remained painfully slow, since it required rethinking its causes and finding practical remedies. Denouncing the neoclassical assumption that the market would right itself through austerity, the Cambridge don John Maynard Keynes argued vigorously in his 1933 treatise The Means to Prosperity that government needed to take a more active role. Unemployment could be ended only by public pump priming in order to restimulate demand, and the borrowed funds that might be needed for such stimulation could be repaid when the economy was once again flourishing. Socialist theoreticians like former German finance minister Rudolf Hilferding and the Swedish sociologist Gunnar Myrdal also argued that a government stimulus was necessary to break the downward cycle. Only when politicians who were unwilling to change course like the “hunger chancellor” Heinrich Brüning in Germany and the ineffective president Hoover in the United States were removed from office could prosperity return.39 Overcoming the depression therefore required a change of public mind and new leadership.

An initial step toward improvement was cutting away the tangle of reparations and war debts that inhibited the restoration of international finances. Just before the Wall Street crash, a committee headed by the American banker Owen D. Young had proposed to scale back German obligations to 112 billion gold marks to be paid off during a period of fifty-nine years, with half the annual amount of 2 billion fixed and the other depending on capacity. When U.S. loans dried up, President Hoover was forced to broker a one-year moratorium on German reparations in the summer of 1931, since Berlin’s bank failures made it impossible to continue regular installments. Finally, the Lausanne Conference of 1932 reduced German obligations by a further 90 percent in order to assure at least some payment. But at the same time Hoover, the Congress, and the U.S. public refused to cancel the inter-Allied war debts, which would have cut the Gordian knot. As a result, the multilateral effort of the World Economic Conference in the summer of 1933 to reduce tariffs and encourage international trade failed, and countries thereafter pursued nationalist policies.40

Another move toward recovery involved abandoning the gold standard, which had kept currency values artificially high and made European goods less competitive. In the summer of 1931 a run on the pound triggered a sterling crisis, since London’s loans to Germany were frozen and the British economy had lost its invisible earnings abroad. Ramsay MacDonald’s Labour cabinet fell over the reduction of unemployment benefits, and the succeeding national government was dominated by conservatives like Philip Snowden as chancellor of the exchequer. Nonetheless, the speculative pressure forced Britain to abandon the gold standard on September 20, 1931, shocking the world of international finance. During the next six months the pound, originally valued at $4.86, lost about 30 percent of its value, making English products more competitive in foreign markets and thereby dampening the effect of the depression among the countries of the sterling bloc. While Japan followed suit, other states like the United States and Germany feared inflation and resisted devaluation, thereby deepening the depression.41 Because of this chain reaction, the British abandonment of gold ended an era.

Countries like France, which clung stubbornly to bullion, experienced even greater difficulty in coping with the depression as a result of their procrastination. Initially Paris was hardly worried, since France was less industrialized than Britain or Germany and had more small farms as well as greater financial savings, making the downturn less marked. In order to reassure the class of rentiers, French cabinets constructed a “gold bloc” to defend the currency and instituted deflationary measures. Their inability to end the depression eroded parliamentary stability and encouraged rightist protests in the wake of the Stavisky scandal. By 1936 the social suffering grew so severe as to sweep Léon Blum into office with a front populaire, supported by all leftist parties from the Radicals and Socialists to the Communists. Trying to “restore consumer purchasing power,” Blum finally devalued the franc, instituted a forty-hour work week, and modestly raised wages with the Matignon Agreement. Though the Popular Front managed to regain full employment, productivity lagged, and production grew only slowly. Therefore the Daladier cabinet returned to more orthodox policies without improving the result. By increasing the ferocity of social conflicts, the depression fatally weakened French democracy.42

The only democracies that actually prospered during the depression were Sweden and to a lesser degree its Scandinavian neighbors. This positive record was the result of Rudolf Kjellen’s conservative corporatism, stressing national cooperation, and of the Social Democrats’ abandonment of the class struggle. Instead, in 1928 Per Albin Hansson suggested the concept of a folkhemmet, arguing that the country ought to be run like a good “people’s home” with everyone having a decent chance in life, regardless of social origin. Concretely this program envisaged a planned economy, which would be controlled by government regulation, and the extension of welfare benefits such as unemployment insurance and the construction of subsidized housing. By ending industrial strife, this approach built on a secularized search for social consensus, which characterized Swedish Lutheranism.43 Expanded by successive Social Democratic prime ministers, the Swedish welfare-state model offered a third way between capitalism and communism.

The most radical response was the nationalist program pursued by the Nazi government that took power in Germany on January 30, 1933. One of its first measures was the institution of a Reich Labor Service (RAD) that compelled young men and women to spend one year in physical labor.44 A second step was the initiation of vast public works, such as the building of superhighways (the famous Autobahnen) and also military defenses such as the Westwall. Another policy was the initially clandestine but eventually open rearmament project, a massive effort to produce weapons systems such as tanks, airplanes, and battleships forbidden by the Versailles Treaty. A fourth approach was the striving for autarchy, which entailed subsidizing domestic production and raising tariff walls in order to become self-sufficient in food and raw materials. A final move was the signing of bilateral trade agreements to create a German sphere of influence in East-Central Europe. Though financed by borrowing and by freezing wages, these measures returned full employment and restored production, making Germany look more dynamic than its democratic competitors.45

Owing to the depth of the depression, the recovery took years to accomplish, since it was not clear which measures would be most effective. In response to the breakdown of international finance and trade, most countries first sought to save themselves, devaluing their currency, controlling exchange rates, raising protective tariff walls, or resorting to barter. This nationalistic response actually prolonged the agony. When laissez-faire belt-tightening failed to produce a rebound, most European states reluctantly switched to deficit financing in hopes of reversing the deflationary spiral. Social democratic governments in France and Sweden engaged in social reforms so as to stimulate demand by strengthening buying power. The fascist dictatorships instead opted for public-works programs and extensive rearmament, while the Soviet Union sought to industrialize. Ultimately it was the rise of military expenditures that speeded the recovery. Only the outbreak of the Second World War ended the depression—but at what a terrible price!46

DOUBTING DEMOCRACY

It is hard to exaggerate the disastrous effect of the Great Depression, because it turned European development from a positive course to a negative direction. The great slump shattered the growing optimism that the Old Continent was healing the wounds of the First World War and resuming the progress of modernity. At the same time the breakdown of international cooperation strengthened the forces of nationalism, which pursued selfish economic policies at the cost of hurting their neighbors. In Berlin and Vienna, the depression toppled democratic governments, initiating authoritarian regimes that would eventually turn into a brutal National Socialist dictatorship. Since the industrializing Soviet Union escaped the effects of the downturn completely, communism attracted western intellectuals who doubted whether their divided democracies could survive. As “the seminal macroeconomic event of the twentieth century,” the Great Depression triggered the reversal from a promising postwar trajectory to another gloomy prewar period, in effect marking the decisive turning point of the interwar era.47

Oral testimonies of the 1930s indicate that contemporaries experienced the depression as “hard times” of intense suffering and disorientation. Although living costs dropped by about one-fifth, salaries and wages of those who could hold on to jobs declined even further, forcing them to get by on less and making them worry about the future. Even harder hit were the unemployed, since public assistance barely sufficed to keep body and soul together. After their meager savings were used up, there remained nothing but “the lowest depth of misery and degradation.” Picking up cigarette butts to roll their unburned tobacco into smokes, standing in soup-kitchen lines, and begging in the streets somehow passed the time. For men, used to being able to provide for their families, joblessness meant shame, shifting power to harried women in their search for scraps of food. The proud solidarity of union membership evaporated, because the abundance of desperate laborers made strike threats ring hollow. Moving testimonies show that the depression had a severe impact on personal lives, upsetting plans and forcing a struggle for sheer survival.48

When neither economic initiatives nor political measures seemed to work, rampant despair cast doubt on capitalism and democracy. Because the self-healing forces of the market failed to reverse the downturn, many victims gave up hope in recovery and turned against the entire capitalist system, decrying it as heartless. Due to the ineffectiveness of political remedies, long-suffering citizens also lost faith in the ability of democracy to solve their economic problems. Liberal middle-class appeals for further belt-tightening fell on deaf ears when there was nothing left to economize. The pleas of Catholic and Protestant leaders to help the unfortunate by benevolent gifts seemed inadequate, since the scale of the need vastly exceeded the capacity of religious charity. Similarly social democratic proposals of job sharing or of increasing public assistance were hardly more convincing, as they appeared only to spread the misery without curing its cause.49 Because of the close connection between the market economy and parliamentary government, the deep crisis of capitalism helped discredit the democratic version of modernity.

The apparent inability of democratic leaders to find solutions to the predicament drove millions of disappointed Europeans into the arms of the totalitarian ideologies that proposed alternative visions of progress. One beneficiary was communism, since the planned economy of the Soviet Union seemed impervious to business cycles. Stalin’s collectivization and Five Year Plans produced spectacular growth rates just when capitalist economies were in the greatest difficulty. Scores of leftist intellectuals like Sidney and Beatrice Webb therefore admired Russia and enthusiastically endorsed the Soviet experiment, ignoring the immense human cost of the purges and the gulag. To sympathetic heirs of the Enlightenment, the communist utopia offered a better road to modernity, since it promoted rational planning, social equality, and economic security at a time when the West was struggling. The French pacifist Romain Rolland expressed the sentiment of many European writers, artists, and commentators when he described the Soviet Union as “the hope, the last hope for the future of mankind.”50

Another profiteer was fascism, since its rejection of both democracy and communism promised to restore a mythical sense of community. In Italy Mussolini, for all his own difficulties, put on an impressive show of national strength that impressed even Winston Churchill. In Nazi Germany, the recovery appeared to proceed faster and more successfully than in hesitant Britain or troubled France, creating an image of dynamism that attracted impatient bourgeois youths from all over the continent. Cultural pessimists like Oswald Spengler, anti-Semitic writers like Louis-Fernand Céline, and misguided poets like Ezra Pound looked to Hitler to stem disorder, defend elite standards, and restore national community. Disturbed by the dissolution of order and hierarchy, neoconservative thinkers like the philosopher Martin Heidegger imagined the fascist movement as a cure to the decadence of liberal civilization.51 These sympathizers tended to overlook the fact that the Nazis were themselves conflicted over whether to revive older traditions or to promote another organic, even more deadly, version of modernity.