HITLER’S VOLKSGEMEINSCHAFT

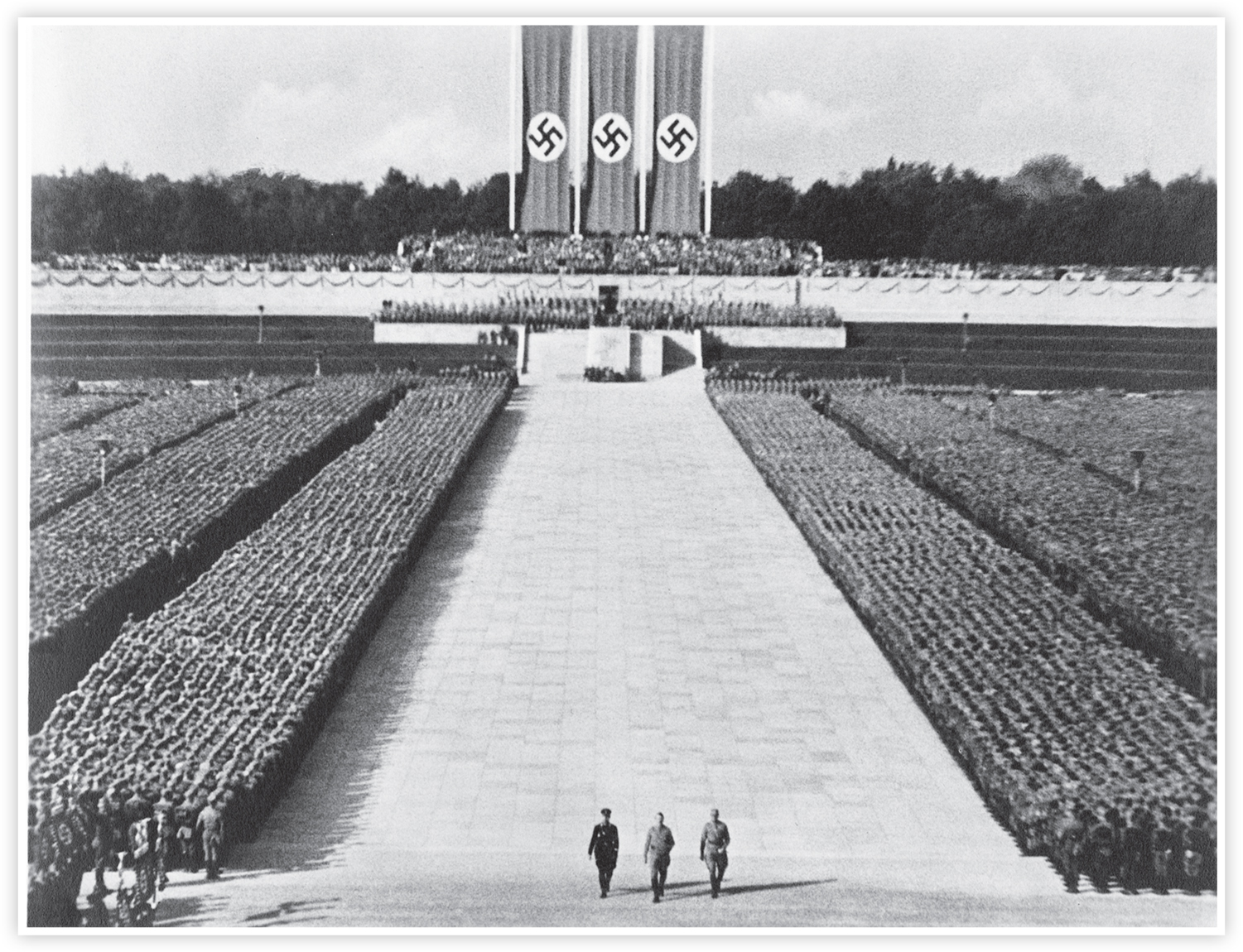

Nazi Party Congress, 1934. Source: Library of Congress.

On January 30, 1933, German radio broadcast the momentous news that Adolf Hitler had just been appointed chancellor. Due to the failure of the preceding minority cabinets, which he had supported by his emergency decrees, President Paul von Hindenburg had entrusted the government to the leader of the largest Reichstag party. In Berlin, nationalists and Nazis were overjoyed by their joint seizure of power, gathering before the presidential palace and staging a gigantic demonstration. “Throngs of singing and chanting civilians jubilantly hailed the storm troops who had gathered in the Siegesallee for a torchlight parade.” Onlookers were impressed when “column after column, with waving swastika banners, swung through the Brandenburg Gate down Unter den Linden, which was jammed by jubilant crowds of Nazi sympathizers.” The Republican aesthete Count Harry Kessler marveled at “the pure carnival atmosphere.” But many workers tried to resist, sometimes even by force, while intellectuals like the literature professor Victor Klemperer had dark forebodings: “It is a disgrace which grows worse every day.”1

The National Socialists (NSDAP; informally, Nazis) were anything but a normal party, since they considered themselves a radical movement, pursuing a “program of cultural and social regeneration.” Founded in Munich in the wake of Germany’s defeat in the First World War, the NSDAP embodied the multiple resentments of the Right against the humiliating Treaty of Versailles and the politicians of the Weimar Republic that sought to fulfill its terms. But the Nazis differed from conventional conservatives by not wanting to go back to the empire; instead they sought to recapture that feeling of national unity which had inspired the war effort and to create a true people’s community, erasing class distinctions, religious differences, and regional divergences. As a reborn nation, Germany would then be strong enough to risk another trial of arms that would bring ultimate victory. Ironically, it was an Austrian-born failed artist by the name of Adolf Hitler who led the movement by styling himself as its charismatic Führer, a leader with superhuman insight.2 This was therefore a dynamic right-wing movement that set out to remake Germany fundamentally.

Because of National Socialism’s irrational nature, opinion has been deeply divided about its actual character and its relationship to modernity. Especially in Germany many leftist intellectuals consider the Nazis a quintessentially reactionary movement according to the standards of western democracy or Marxist theory. They like to cite Hitler’s personal distaste for the degeneracy of “modern art” as well as much propaganda rhetoric by Alfred Rosenberg with an anticapitalist, anti-Semitic, anticommunist, and antiurban bent. Moreover, the positive appeals to order, stability, and community suggest a world of small towns and the countryside, ideologically glorified by Walter Darre’s “blood and soil” fantasies. From a western vantage point that equates modernization with the advancement of individual freedom and equality, the racial hatred and genocidal practice of the Nazis seem deeply antimodern, like a flight into an imaginary past. The antifascist perspective therefore asserts that “National Socialism has not accelerated the modernization of Germany, but rather has hindered it.”3

Yet less-ideological commentators insist that the Nazi rejection of modernism was itself a product of modernity since they also embraced it selectively. Already at the time Thomas Mann pondered the “mixture of robust modernity … combined with dreams of the past,” deriding Nazi views as “a highly technological romanticism.” Since leaders like Hitler, Speer, and Goebbels were fascinated by the likes of Mercedes cars, Junkers airplanes, and UFA films, one attempt to resolve the paradox of murderous irrationalism and fascination with technology is the concept of “reactionary modernism.” Another approach asserts that the biopolitical engineering with which the SS tried to reshape the physical body and the racial composition of the nation was based on faith in science, exaggerating tendencies such as eugenics present in other countries as well. For all their rhetorical denunciation of decadence, the Nazis also vastly expanded the reach of the media by creating a popular entertainment and consumer culture.4 While National Socialism rejected urban decadence, such features suggest that it was ultimately searching for its own alternative vision of an “organic modernity.”

The Nazis’ simultaneous rejection and embrace of modernity holds the key to their puzzling seizure of power in a country that prided itself on its contributions to European culture. In parts of the Islamic world and among skinheads the Nazi swastika still exerts a prurient fascination, while no theory, such as that of Hitler’s missing testicle, seems to be too far-fetched to be believed. On the one hand it is important to remember that Hitler profited from the failure of liberal democracy in the Weimar Republic, which allowed him to exploit the Great Depression demagogically. Moreover, fear of a Bolshevik-style revolution drove many voters into the Nazi camp because they promised to offer protection against communist leveling. On the other hand, the Nazis themselves used up-to-date techniques to broadcast nationalist appeals to their male and lower-middleclass supporters, promising them a strong and harmonious national community. Once in power, the NS dictatorship also employed a modern mixture of incentives and repression to cement its popularity. And yet, even after such rational considerations, an element of inexplicable mystery tends to remain.5

AGONY OF THE REPUBLIC

Dramatized in Christopher Isherwood’s Berlin Stories, the fate of the Weimar Republic reads like an ancient tragedy, beginning with hope and ending in disaster. In retrospect, the failure of the first German democracy looks almost overdetermined, since its endless problems appeared to doom it from the start. Many factors seem to explain the collapse such as the lack of a social revolution, the resentment of a punitive peace, the ambivalence of the Reichswehr, and the flaws in the constitution. Intellectuals therefore like to invoke the “Weimar analogy” to warn against the danger that democracy will erode if authoritarian tendencies are not stopped from the start. Nonetheless, Weimar culture continues to exert a strange fascination as an extraordinary moment of modernist experimentation that inspired innovative styles all over the world due to its forced dispersal. In order to do justice to the modernizing potential of the Weimar Republic, it is necessary to put aside the teleological fixation on its ending and also to examine its chances for success as well as appreciate some of its lasting contributions.6

Ending four and one-half years of war, the November Revolution of 1918 inspired hopes for peace, political participation, and social equality. Virtually overnight, the revolt of war-weary sailors, soldiers, and workers overthrew the imperial structure, discredited by defeat: “The Kaiser has abdicated. The revolution has been victorious in Berlin.” Led by the radical Spartacists and shop stewards, the hungry masses wanted to create a Soviet-style council system in order to expand participation and social equality. But ultimately the moderate majority of the Social Democrats (SPD) won out, insisting on the creation of a democratic republic, headed by a parliamentary government. Newly elected president Friedrich Ebert of the SPD negotiated a compromise with the army leadership, which promised to tolerate the republic, while unions and employers agreed to treat each other as legitimate social partners. The January 1919 election therefore returned a left-center majority for the Constituent Assembly in Weimar, which drafted a progressive constitution that guaranteed extensive civil rights.7

Yet social cleavages and political divisions deepened, bringing the country to the brink of civil war. Following the Soviet model, the Spartacists staged an ill-advised uprising in Berlin that the government put down with military help, culminating in the murder of their leaders Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg. The announcement of the Versailles Treaty’s harsh terms and the accusation of war guilt created “incredible dejection” across all party lines, leading to the fall of the cabinet and strengthening the hand of obdurate nationalists. Emboldened by the paramilitary units of the Free Corps, East Prussian bureaucrat Friedrich Kapp launched a right-wing putsch ostensibly to restore order, which failed due to the resolute resistance of the trade unions. Hence the major political parties created uniformed auxiliaries like the veterans’ Stahlhelm, the Socialists’ Reichsbanner, the Communists’ Rotfront, and the Nazis’ Sturmabteilung (SA) to battle for control of the streets. Although the government survived these challenges, the proliferation of extremist violence weakened the republic, since it was never able to assure security.8

After weathering such unrest, the first German democracy consolidated during the mid-1920s under the capable leadership of Gustav Stresemann. While unpopular policies cost the Weimar coalition of working-class Social Democrats, bourgeois Democrats (DDP), and the Catholic Center Party its parliamentary majority, the national-liberal middle-class German People’s Party (DVP) took up some of the slack, shifting the cabinets to the center-right of the spectrum. Though Stresemann had been a rabid nationalist and supporter of the kaiser, political realism made him moderate his views sufficiently to accept the republic and help negotiate the Dawes Plan, which ended the hyperinflation and produced a more tolerable reparations schedule. In contrast to much of the elite, he saw international reconciliation as the best way to revise the onerous clauses of Versailles, cooperating in the spirit of Locarno with French statesman Aristide Briand.9 While the leftist Communists and the right-wing German National People’s Party continued to reject democracy, the economic recovery helped stabilize the republic politically.

Weimar’s halcyon years made possible exciting experiments in democratic modernity that sought to better the lives of the toiling masses with all sorts of innovations. Leftist politicians sponsored social reforms such as reducing the length of the workday and extending unemployment benefits. Progressive architects like Bruno Taut built improved workers’ apartments, using green spaces for more “light and air” than in the usual dingy rental flats. Socially concerned doctors campaigned for improved hygiene, seeking to decrease mortality by public support for preventive medicine. While advertisers promoted an androgynous “new woman,” sexual reformers like Magnus Hirschfeld campaigned for access to contraception and decriminalization of abortion as well as homosexuality. At the same time philosophers like Martin Heidegger, artists like Georg Grosz, and intellectuals like Carl Schmitt explored the contradictions of life in the metropolis.10 With their boldness, these emancipatory initiatives, daring experiments, and ideological discussions created a sense of unprecedented social and cultural modernity.

The Great Depression not only ended the hopeful mood; it also dealt German democracy a blow from which it did not recover. In some rural areas like Schleswig-Holstein the fall of agrarian prices sparked a protest movement against the Weimar system that used terror to destabilize the countryside. In the cities, unemployed workers flocked to the radical Communists while the Social Democrats had difficulty in maintaining their support by promising additional welfare measures. Faced with the threat of destitution, much of the middle class abandoned its allegiance to democracy, while many members of the economic, military, and administrative elite campaigned for an authoritarian dictatorship. When the unemployment insurance fund went bankrupt owing to the huge number of jobless, the grand coalition under SPD chancellor Hermann Müller fell apart, since it could not agree on how to meet the emergency: The Left wanted to raise business taxes; the bourgeois right insisted on cutting benefits. Hence President Paul von Hindenburg appointed the conservative Center Party politician Heinrich Brüning chancellor.11

Since austerity measures and revisionist confrontation remained unpopular, the republic gradually turned into an “authoritarian democracy.” When the electorate rejected Brüning’s policies in July 1930 by dramatically increasing the number of NSDAP and Communist (KPD) seats, he resorted to paragraph 48 of the constitution, which envisaged rule by presidential decree in case of a national emergency. Since deflationary measures failed to end the depression, Hindenburg lost patience, because the Junkers around him opposed Brüning’s plan to distribute land to the unemployed in the East. In May of 1932, the president appointed Catholic nobleman Franz von Papen, whose dashing bearing was matched by his political incompetence, as chancellor. But when he lost the July election and failed to get parliamentary backing, the president was at his wit’s end. Egged on by his conservative camarilla, the octogenarian Hindenburg named the head of the Reichswehr, General Kurt von Schleicher, as chancellor in December.12 Within two years a struggling parliamentary democracy had turned into an autocratic presidential regime.

The Weimar Republic failed because of a combination of underlying structural problems and short-term contextual causes. As the cliché of the “Republic without republicans” indicates, only the working class and the liberal Bürgertum were ready for self-government, since many members of the elite remained hostile to mass participation. Negative circumstances such as military defeat, an onerous peace treaty, hyperinflation, civil strife, and the Great Depression did not help endear democracy to the population either. Moreover, mistaken policies, ranging from the confrontation over reparations and foreign-policy revisionism to the failure to dismiss the old elites, the toleration of private armies, and the austerity response to the depression, contributed to the collapse. As a result, citizens who had reserved judgment about parliamentary government distanced themselves from it when they felt disappointed that it could not deliver on its promise.13 In the end, Weimar’s fall was merely the German variant of a more general rejection of democratic modernity in the interwar period, though it had more disastrous consequences by far.

FÜHRER FROM THE FLOPHOUSE

The ascent of a “bizarre misfit” like Adolf Hitler to power in a cultured country like Germany continues to strain credulity. His central role in the rise of the Nazi movement can be attributed to his exceptional abilities, the cult of the Führer, and the polycratic competition between collaborators that reserved all decisions ultimately for him. Though he was often underestimated by his competitors, part of his success was also due to his extraordinary personality, a strange mixture of talents and liabilities. Highly effective as propaganda, the Charlie Chaplin parody in The Great Dictator has actually made understanding Hitler’s ascendancy more difficult by ridiculing his odd mannerisms. But poking fun at his outlandish personality traits fails to clarify the reasons why so many people would go along with such an exalted individual. To explain this surprising bonding, Max Weber’s notion of “charismatic authority” offers an important clue, because it links an aura of leadership with a mass following.14 The secret of Hitler’s success lay in the peculiar relation between his personality and the public.

Since Hitler mythologized his background, it is necessary to recall a few simple facts. He was born in 1889 as the son of an Austrian customs official in Braunau on the Inn River. Unlike his authoritarian father, his mother was a simple, doting woman who failed to discipline the young Adolf. In the provincial town of Linz, he attended the Realschule with a modern curriculum, though he dropped out after his father’s death in 1905. After two years of idleness, punctuated by a passion for Wagner operas, the eighteen-year-old moved to the capital of Vienna, where he twice failed the entrance examination to the Austrian Academy of Fine Arts. Stymied in his grandiose plan to become an artist, he used up his inheritance after his mother’s death by refusing to take on regular work. When his money ran out, he was reduced to poverty, an unkempt young man with lice-infested clothes, sleeping in hostels and selling postcards and paintings. Though a bequest from an aunt improved his situation, he remained a déclassé bohemian who listened to the anti-Semitic rants of Georg von Schönerer and read rightist pamphlets full of hatred for the Reds and Slavs.15

The outbreak of World War I suddenly gave his life new purpose and direction, since Hitler was swept up by the national enthusiasm. In order to evade military service in Austria, which he considered moribund, he had previously moved to Munich, where he eked out a modest existence as a painter. In early August 1914, he volunteered for the Bavarian army and was inducted into the List regiment, which became his physical and psychological home for the next several years. At the western front, he served as a dispatch runner, carrying messages from regimental headquarters to the trenches and back, a dangerous undertaking in which he was wounded. Though brooding and moody, he felt secure in the comradeship of his fellows, serving with enough courage to be promoted to corporal and earn the Iron Cross first and second class. In October 1918 he was gassed, experiencing the end of the war in a military hospital in Pasewalk. The unexpected defeat shattered his nationalist universe, robbing his life of structure and meaning.16 Distraught, he sought explanations for the disaster, blaming the Left and the Jews.

Back in Munich, the thirty-year-old Hitler became a beer-hall orator who galvanized a crowd with his simple, emotional harangues. The Bavarian capital was torn between the council republic of left-socialist revolutionaries and counterrevolutionary forces of local and national reactionaries. In this chaos, Hitler became an informant of the nascent Reichswehr, discovering a talent for speaking in propaganda courses designed to keep the troops loyal. In September 1919, he attended a meeting of the radical German Workers’ Party, which he joined as number 555, sensing that he might play a leading role in this small organization. In the fragmented scene of competing rightwing movements, Hitler quickly made a name for himself with his impassioned rhetoric that attacked communists and Jews, calling for a national rebirth. The twenty-five-point party program was a mélange of various resentments, blending nationalist with anti-Semitic and anticapitalist themes. As a result of his rhetorical ability as “a drummer” Hitler quickly took over the control of the renamed National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP).17

Emboldened by growing success, Hitler in November 1923 decided to launch a putsch in order to topple the government in Berlin. His fiery speeches had attracted followers such as the lawyer Hans Frank, flying ace Hermann Göring, and Captain Ernst Röhm, who created the paramilitary SA, swelling the party’s ranks to about fifty thousand members. After Mussolini seized power in Rome, Hitler began to style himself as Führer and decided to follow his example, since the Ruhr struggle against French occupation and the hyperinflation had made the national government look ineffectual. On November 8, 1923, Hitler stormed into a mass meeting in the Bürgerbräukeller and tried to compel leaders of the conservative Bavarian government who were there to join him in proclaiming a national revolution. But when the Reichswehr balked at his coup and the regional reactionaries rejected his demands, a debacle ensued. On the following morning the police fired on the Nazi demonstration on the way to the Feldherrnhalle, killing fourteen insurgents. Marching in front with Ludendorff, Hitler barely escaped alive, only to be imprisoned in the Landsberg fortress.18

The failure of the Beer Hall Putsch forced Hitler to switch to a legal strategy after his release in December 1924. He used his time in prison to formulate his worldview in Mein Kampf, a turgid collection of anti-Semitic and anti-Bolshevik ravings as well as nationalist attacks on the peace treaty and calls for “living space.” During the consolidation of the republic, he refounded the NSDAP under his own leadership and made it preeminent among the competing right-wing groups. With the help of Gregor Strasser’s organization and Joseph Goebbels’ propaganda, he also expanded the reach of the party into northern Germany. Initially the strategy of a legal quest for power yielded only local gains such as twelve Reichstag seats in the 1928 election. But soon the Great Depression sparked so much rural radicalism and urban despair that membership numbers swelled and donations multiplied. The breakthrough came in September 1930, “a black day for Germany,” when the NSDAP jumped to 107 seats. Two years later street violence and incessant agitation against the “Weimar system” helped the party to obtain 37.1 percent of the vote, winning 230 deputies’ seats.19

Once the Nazis were the largest party, any solution to the government crisis had to include them in some fashion. But President Hindenburg was suspicious of the Austrian upstart while Hitler wanted nothing less than the chancellorship and control of the government. This stalemate was broken only when the number of Nazi seats decreased to 196 in the November election, suggesting that the peak of their popularity might have passed. Outmaneuvered by Schleicher, his predecessor Papen finally realized that he could return to power only if he accepted Hitler’s leadership. In complicated negotiations between the NSDAP leaders, Hindenburg’s circle, and the conservatives, a compromise was eventually reached: Hitler would become chancellor, but only the jurist Wilhelm Frick and Göring would join him as Reich and Prussian ministers of the interior. Papen would be vice-chancellor, supported by the reactionary press tycoon Alfred Hugenberg and a bevy of conservative noblemen. Ironically, this NSDAP and DNVP coalition seemed almost to be a return to democracy, since it represented just over two-fifths of the popular vote.20

Part of Hitler’s success was therefore due to his extraordinary personality, which set him apart from other politicians. Caricatures of the man with the mustache, burning eyes, and fixed expression overlook that his speaking ability enthralled crowds, his emotional intensity inspired a movement, and his personal magnetism attracted followers. After lengthy hesitation, he often guessed right in his political gambles. Critics correctly pointed out that he was an odd person: moody, lazy, brooding, and given to fits of temper. With his vegetarianism, refusal to smoke and consume alcohol, and disinterest in womanizing, he deviated considerably from the machismo image expected of politicians. But somehow he managed to turn his liabilities into assets, transforming difference into evidence of superiority so as to justify his ascendancy and expect devotion. Facilitating his rise, bourgeois patrons like the Bechsteins helped refashion his appearance, behavior, and speech patterns so as to make him look more impressive. Finally, the photographer Heinrich Hoffmann contributed to the Führer myth by picturing him in various studied poses, suggesting a modern style of leadership.21

APPEALS AND FOLLOWERS

Another secret of Hitler’s success was the pervasive sense of crisis, which made his extremist ideology appear as the only way out of a threatening catastrophe. Under normal circumstances, the strident simplifications of his rhetoric would have repelled sensible voters, but during the depression and the disintegration of the republic, his message found increasing resonance. Nazi appeals were a collection of resentments against what seemed to be going wrong in Germany, augmented by a pseudophilosophical rejection of negative aspects of modernity. But Hitler also offered a positive, if rather hazy, vision of national rebirth and people’s community that promised to lead the country into a better future. Much of the propaganda was contradictory, appealing to different groups, and difficult to pin down because of its irrationality, but the very actionism radiated a sense of resolve, finally, to do something that would improve the situation.22 Rejecting the squabbling of democracy and the violence of Bolshevism, the Nazis proposed a different, more organic modernity for the national community.

Much of Hitler’s invective was directed toward mistakes of the recent past and the predicaments of the present. He derided the November Revolution as “the greatest villainy of the century” and explained the defeat of the army, “victorious in a thousand battles,” as a result of “internal decay.” In social Darwinist terms he argued: “The deepest and ultimate reason for the decline of the old Reich lay in its failure to recognize the racial problem and its importance for the historical development of the peoples.” He railed against the “shameful peace” of Versailles, signed by the “November criminals” who created the weak Weimar Republic, leading to “a rampant degradation, which gradually consumes our entire public life.” As an ardent nationalist Hitler deplored how the German people had been “mugged by a pack of rapacious enemies from inside and outside,” and tried to rouse them to militant resistance. The misery of the Great Depression, which caused “fighting for the daily bread of this people,” could only be cured by conquering “necessary space” to live in.23 Such resentments were shared by an increasing number of confused patriots.

Hitler’s ambition, nonetheless, aimed at providing a deeper understanding of Germany’s malaise in order to offer a more lasting cure. Departing from the premise that “it is the highest task of politics to preserve and continue the life of a people,” he claimed that maintaining biological health required safeguarding the “racial purity” of the nation. In a terrible misreading of history, he argued that all high cultures had collapsed because “the originally creative race died out from blood poisoning.” In Germany, he saw the superior Aryan race beset by two mortal enemies—the Jews and the Bolsheviks. Lacking a territory of their own, the former were by definition a “parasite in the body of other nations” and thereby ultimately destructive. Inspired by Jews, the Marxists were also violently corrosive of civilization, since they focused on social leveling. His other objections to capitalism and feminism were derived from these presuppositions, even if such deductions were hardly logical.24 With his racist nationalism Hitler rejected the entire thrust of emancipatory progress, derived from the Enlightenment.

In much vaguer terms than his phobias, Hitler also tried to sketch a positive image of national rebirth, centered on the notion of a “people’s community.” Germany could only be revitalized by obeying the dictates of “racial hygiene,” creating a body politic cleansed of biological and racial inferiors. In order to regain the health of its blood, the nation had to live on the soil, tilling the land and drawing strength from it. In contrast to bourgeois hierarchy and Marxist class struggle, the Volksgemeinschaft would treat all members equally, while respecting a hierarchy of achievement. By repairing the effects of urban decadence, the national community would also recover its fighting prowess, making it capable of enduring the necessary battles. In this partly military, partly biological enterprise, gender roles were clearly defined, with men as warriors and women as reproducers of the race. Seeking to recapture the emotional unity of the Great War, such a nation transformed would leave behind the partisan squabbles of democracy and dedicate itself to achieving greatness by working together with enthusiasm.25

A “truly German democracy” was supposed to combine atavistic myths with modern innovations in a novel blend that would make the nation more powerful. At its head would be the freely elected leader, obligated “fully to assume all responsibility for his actions and omissions.” The Führer’s vision would be propagated by a political movement of dedicated followers, creating a dynamic bond of national resolve. The masses had to be won over by propaganda, since they were like women, easily swayed and dominated by an iron will. Of course, all enemies such as Jews and Bolsheviks would be ruthlessly excluded. A new elite would arise to implement this combination of visionary leadership and popular acclamation, capable of highest achievement and ready for heroic action. In such a conception, science and technology played an important role by providing tools for propaganda, rearmament, and biopolitics. This entire concept of the Führerstaat was an effort at social engineering that was distinctly modern, even if it proposed an illiberal racial alternative to the democratic and Marxist ideologies.26

The followers who joined the NSDAP began as a small band of extremists but eventually grew to a virtual cross section of German society. During the initial struggle only convinced reactionaries dared to commit to a party that was considered part of the radical fringe. The Nazis attracted some workers, but more came from the lower middle class and marginal members of the elite. From the late 1920s on, the Great Depression drove new converts to National Socialism, mostly recruited from the middle class, which feared social descent, and from among the young, blocked in their careers. After the 1932 electoral triumph many opportunists, hailing from the administrative ranks, professions, and technical pursuits, flocked to the swastika banner, wanting to join a movement that looked like the wave of the future. Finally, once in the saddle the Nazis could use the lure of privilege to attract members from the previously skeptical elites and could rely on their own youth organization as a recruiting ground. Containing over eight million members by 1945, the Nazi Party systematically moved from the fringes into the center of German society.27

Nazi electoral support similarly expanded from a limited core to a mass following approaching a people’s party through appeals to the losers of modernization and to protest voters. The NSDAP made some inroads among blue-collar workers but could never win over the majority of the proletariat. Its nucleus was instead composed of struggling small farmers, shopkeepers, and independent artisans, complemented by white-collar employees who were especially battered by the economic crisis. Moreover, the party also found a surprising amount of support among university students, civil servants, and in affluent districts where the nationalist message resonated. While the young were especially susceptible, a considerable number of retirees also voted for the party, and women, who were underrepresented among the members, cast their ballots for Hitler as well. The typical Nazi follower was therefore a young Protestant World War I veteran with limited education. The NSDAP especially managed to mobilize many formerly apolitical voters who were strongly dissatisfied with the Weimar Republic.28

In essence, National Socialism offered a more dynamic and modern version of the radical Right by using the economic and political crisis of the republic to broaden its appeal. In spite of all propaganda efforts, most of the working class remained committed to the Social Democrats, while the unemployed tended to vote Communist. Similarly, religious authority immunized the Catholic milieu somewhat against nationalist appeals, so that many of its faithful remained skeptical. In contrast, the democratic and liberal middle-class parties crumbled, first transforming themselves into special-interest groups and then fading entirely from the scene, as they lacked an encompassing vision. The German National People’s Party failed to profit from the chaos, because it was too backward looking, hoping to bring the kaiser back and revive the discredited empire. The Nazis instead projected an image of dynamism, ready to shape the future by promising a national renewal that would restore external power and heal internal rifts.29 This combined message of past resentment and future hope captured an increasing number of Germans.

NATIONAL REVOLUTION

While the “national renewal” was mostly a propaganda show, Hitler managed to establish a dictatorship with surprising speed and thoroughness, outwitting his opponents and partners. Since he was only the chancellor of a coalition government in which the DNVP held a strong majority, the traditional elites were confident they could control the agitator. Skeptics predicted that “the apparition will not last long, since the Nazis and Papen-Hugenberg are bound to clash.” But the SA terror against communists and Jews in the streets, abetted by Göring’s Prussian police, proved that this was an illusion, because the Nazis refused to respect any legal limits. Intimidated by the outpouring of nationalist propaganda, cowed opponents just disappeared, making a few critical speeches without daring to organize mass resistance or a general strike. During the first weeks Hitler quickly gained the backing of the business community and the army leadership, persuading Hugenberg to agree to the dissolution of the Reichstag. Under the cover of a “national revolution,” the Nazis set out to establish a racial dictatorship.30

The Reichstag fire presented Hitler with an unplanned chance to expand his power by suspending civil rights and arresting the Marxist opposition. On the evening of February 27, 1933, the young Dutchman Martinus van der Lubbe set fire to the parliament building in protest against the lawless violence of the Nazis. Although nobody believed the charge of “Communist arson,” the quickly assembled Nazi leaders recognized the act as “a heaven sent, uniquely favorable opportunity” that allowed them to issue an emergency decree “For the Protection of People and the State,” which simply abolished all civil rights enshrined in the Weimar Constitution. Göring not only “had the entire Communist Reichstag caucus, but hundreds, even thousands of Communists arrested all over Germany” as well as many Social Democrats and trade-union leaders locked up and the leftist press forbidden. As a result of such repression, the election campaign turned into a highly uneven contest. When the votes were counted on March 5, the Nazis had won 43.9 percent and the DNVP 8 percent, barely constituting an absolute majority.31

The Enabling Act of March 23 formalized the National Socialist dictatorship, since with it the Reichstag practically abolished itself. Encouraged by the “inordinate electoral victory,” the Nazi terror in the streets continued: “Nobody breathes freely any more, no free word is spoken or printed.” Yet Hitler also strove for a veneer of legality, meeting with the aged president Hindenburg in the garrison church in Potsdam in order to symbolize the reconciliation between Prussian traditions and the radical volkish movement. Moreover, he harangued the Reichstag in a bid to change the constitution fundamentally by adding the seemingly innocuous clause that “laws of the Reich may also be enacted by the government of the Reich.” Though the Nazis promised to leave the Reichstag and the president untouched, this stipulation transferred legislative power to the cabinet, thereby legalizing dictatorial rule. In order to preserve the Catholic Church, the Center Party joined the Nazis and the Conservatives in the decisive vote of 441 to 94. Only the Social Democrat Otto Wels had the courage to warn against the disastrous abolition of humanity, freedom, and justice.32

A mixture of violent intimidation and voluntary cooperation Nazified German society during the spring and summer of 1933 in a process called Gleichschaltung, or coordination. First, the national government seized control of the various states by appointing Reich governors. Then all opposition parties reluctantly dissolved themselves, since they had become superfluous. Moreover, the once-mighty trade unions fell into line by joining the celebration of May 1 as “day of national labor.” At the same time, the universities purged themselves of democrats, Marxists, and Jewish professors, while professional associations expelled Jews, forced liberals to resign, and elected nationalist officers who transformed their organizations into Nazi auxiliaries. Even the Catholic Church signed a treaty with the Third Reich in which the Vatican permitted the dissolution of its civic associations so as to preserve its religious core. Typical of rising nationalist intolerance was the “action against the un-German spirit,” organized by the Nazi Student League, which burned thousands of books by leftist authors like Karl Marx, Heinrich Heine, Sigmund Freud, Bertolt Brecht, and Kurt Tucholsky.33

The bloodbath of June 30, 1934, resolved growing tensions between the continuation of the revolution and the pursuit of respectability. Though Hitler sympathized with the radicalism of many followers who beat up Marxists and harassed Jews, killing about five hundred to six hundred people, expediency also dictated that he maintain the goodwill of the established elites and of foreign observers who abhorred violence. One problem was the head of the SA, Captain Ernst Röhm, who flirted with a “second revolution,” hoping to initiate an egalitarian nationalism. A second challenge was the increasing skepticism of the conservatives, voiced by Vice-Chancellor Papen’s warning against trying to live in “a continuous revolution.” When the army chiefs protested against turning the SA into a national militia, Hitler was forced to act. In a “night and fog” action he had the SA leadership executed, while the Gestapo killed conservatives like Schleicher and old rivals like Strasser. Claiming to have stamped out a treasonous conspiracy, Hitler combined his office with the presidency upon Hindenburg’s death in August.34 Now he finally reigned supreme.

The so-called Röhm putsch sent a chilling message to the populace that nobody would be safe in the Third Reich. Among the party faithful the wanton butchery enhanced the Führer myth, because he had elevated himself above all competitors. But the murders struck terror into the hearts of NSDAP opponents such as Heinrich Brüning, Willy Brandt, and Walter Ulbricht, who sought refuge in exile. From abroad they tried to set up resistance organizations, waiting in vain for the Third Reich’s collapse. The book burning forced writers like Bertolt Brecht and Thomas Mann to leave the country, while the university purge expelled eminent scientists such as Albert Einstein and historians like Hajo Holborn, costing Germany some of the best and brightest minds. In the Reich citizens had to learn how to mouth Nazi slogans so that they would not be reported by the countless zealots enforcing nationalist conformity. While the administrative, business, and military elites still enjoyed some latitude, and writers might choose “inner exile,” ordinary democrats, socialists and communists were constantly afraid that denunciation would land them in a concentration camp.35

Hitler’s dictatorship rested not only on repression but also on popular gratitude for the economic recovery, for which he claimed credit. Economists still dispute which of the policies actually worked, but it is undeniable that full employment returned fairly rapidly. In grapeshot fashion, the Nazis launched numerous measures, ranging from public works such as building the high-speed Autobahnen to subsidies for regular construction and reviving industrial investment. Wages initially remained frozen, but the return to work raised the living standards of households that had barely survived the depression and made the Führer popular. Propaganda coups like the production of an affordable radio set, called Volksempfänger, and the design of a people’s car, named Volkswagen, also improved the mood. Most importantly, the massive, initially clandestine, and then open rearmament program, financed by public borrowing with the infamous “Mefo bills of exchange,” contributed to the recovery.36 Though not accepting all facets of National Socialist ideology, many Germans nonetheless appreciated the improvement in their material circumstances.

The final consolidation of Nazi power therefore turned out to be surprisingly easy. With the opposition exiled, fragmented, or driven underground, Hitler replaced the last members of the conservative elites during 1937 and 1938 with hardly a ripple. In short order he fired the financial wizard Hjalmar Schacht, pushed out the army leaders Werner von Blomberg and Werner von Fritsch on trumped-up sexual charges, and dismissed the experienced diplomat Konstantin von Neurath. Their replacements—Walter Funk, Wilhelm Keitel, Walther von Brauchitsch, and Joachim von Ribbentrop—were second-rate NSDAP cronies. Skeptics of National Socialist policy like General Ludwig Beck and Leipzig Mayor Carl Goerdeler remained isolated, since the domestic recovery and foreign-policy successes supported Hitler’s leadership claims. Only emigrants like Sebastian Haffner could warn the world of the Nazis’ murderous character, hoping to undermine their power from without. Inside the Third Reich, intrepid communists and socialists tried to organize an underground resistance, but their efforts yielded few tangible results.37 Within half a decade, Hitler had established a single-party dictatorship.

THE PEOPLE’S COMMUNITY

Chief among the soft stabilizers of National Socialist rule was the rhetoric of the “people’s community,” implemented by an array of subsidiary organizations. Even Germans otherwise opposed to National Socialism shared the aspiration of national harmony superseding class, religious, and regional differences. Goebbels’ propaganda ministry ceaselessly put out slogans like “community comes before the individual” and “one people, one Reich, one Führer” to emphasize national unity, expressed symbolically by eating a simple dish of stew one day a week. No doubt reality never quite lived up to this image of classless solidarity, but the constant repetition of the ideological mantra had some effect, even on the industrial working class. The young were especially susceptible to appeals to idealism, since the need to belong to the Volksgemeinschaft was drummed into their heads in school and the Hitler Youth. Of course, such an inclusive vision presupposed the exclusion of Marxists, Jews, and other enemies. Reports from the security service and Socialist exiles agree that the national community was both a propaganda claim and a partial reality.38

One integrative force was the Nazi Party, which celebrated its unity in the annual rallies held in the medieval city of Nuremberg. Memorialized by Leni Riefenstahl’s seductive reportage in Triumph of the Will, these congresses were carefully orchestrated, quasi-religious ceremonies in which the Führer and his followers of all ranks, from gauleiter to Blockwart, reaffirmed their emotional bond. Arriving by airplane, Hitler would drive in an open Mercedes through the jubilant throng to the parade ground. There tens of thousands of eager members of the party, Hitler Youth, and other National Socialist organizations would welcome him with roaring applause, while the paramilitary units of the SA, SS, and the Reich Labor Service paraded before his reviewing stand. Excitement would reach a fever pitch when the leader himself finally addressed the eager crowd with his strange intonation, exaggerated gestures, and magnetic intensity. The gigantic spectacle was designed to renew the members’ dedication to the Nazi cause, strike terror into the hearts of their enemies, and impress the outside world with the resurgence of German power.39

The German Labor Front (DAF), which absorbed the socialist, Catholic and liberal trade unions, was another important organization supporting the people’s community. The DAF was the creation of Robert Ley, a corrupt alcoholic and philanderer, who strove to fashion an empire of control and service for labor. The revised charter of 1934 envisaged a “factory community,” headed by employers as plant leaders with whom workers as followers were to work harmoniously. Instead of being divided along the collar line, manual laborers and office employees were now to cooperate for the common good. To create a hardworking and docile labor force, the German Labor Front not only suppressed any lingering remnants of Marxist agitation but also offered a series of positive incentives. One policy was the campaign for Beauty of Work, which tried to render the workplace more attractive. Another effort was the Strength through Joy program that offered affordable leisure activities and subsidized vacations so as to restore energy.40 Though some workers resented being muzzled, many also took advantage of such National Socialist initiatives.

The Hitler Youth sought to carry the nationalist and racist message to the younger generation through exciting programs and ceaseless propaganda. Begun as the youth group of the party, it gradually expanded into a compulsory association for children aged ten to fourteen (Jungvolk) as well as boys (HJ) and girls (BdM) aged fourteen to eighteen. In part, its campfire romanticism was a remnant of the volkish Youth Movement, which had made hiking and camping popular around the turn of the century. In part, its paramilitary preparation was a copy of the forbidden Boy Scouts that drilled the young in discipline and prepared them to fight through adventurous war games. Starting with only a few hundred in the early 1920s, the HJ mushroomed under Baldur von Schirach to eight million members by 1940. The heavy demands on time created continual conflicts between the HJ and the schools whenever teachers insisted on their academic subjects rather than glorifying physical athleticism and mental toughness. While a few rebels like the “swing youths” resisted, the Hitler Youth succeeded in indoctrinating many young Germans.41

In spite of Nazi misogyny, women were also an important part of the “people’s community,” since their biological and social contributions assured the continuation of the master race. On the one hand, the uniformed columns of the National Socialist movement rested on male bonding, with a sexist sense of superiority. To ease unemployment, women were forbidden to be “double earners” with state-employed husbands and were limited to 10 percent of the enrollment in the universities, relegating them to the sphere of “children, kitchen, and church.” On the other hand, Hitler’s eugenic obsession with declining birthrates made their reproductive role more significant, creating a female realm that extended the family into society. Under Gertrud Scholz-Klink the National Socialist Frauenschaft built up a Nazi women’s league that engaged in “administering welfare services, educational programs, leisure activities, ideological indoctrination and consumer organization.” Contrary to movie clichés, the Nazis were not prudish about sex, as long as it did not involve miscegenation.42 Hence women were not just victims but also important accomplices of the regime.

The most popular National Socialist organization was the Nazi People’s Welfare (NSV), which strove “to augment and further the vital healthy forces of the German people.” The NSV started as an effort to help indigent party members but gradually developed into the central welfare association of the Third Reich, growing to seventeen million members by 1943. Led by Erich Hilgenfeldt, it replaced the socialist Arbeiterwohlfahrt, directed state welfare efforts, and coordinated the religious charities and the Red Cross. Concretely, the NSV campaigned to improve the situation of “mother and child” by providing counseling and trying to assure sufficient nutrition and health through better hygiene and subsidized vacations. Organizationally separate but propagandistically related were the huge annual collections for the Winter Aid program that appealed to the public for donations so as to assure heat and food during the coldest months of the year. At the same time the NSV also policed the exclusion of racial inferiors and “asocial” persons from reproduction. The goal was less to help needy individuals than to create a healthy body politic.43

Excluded from the imagined “national community” were the political and racial enemies who bore the full brunt of Nazi terror. Hitler’s unbounded hatred for the Left made the “elimination of the Marxist poison from our national body” a top priority, leading to the arrest, imprisonment, and death of known communists. Based on Nazi anti-Semitic racism, the persecution of the Jews was another important goal, leading to a legal purge of public service, the universities, and the professions as well as a grassroots boycott of Jewish business. Victor Klemperer felt as if he were back in medieval Romania: “An animal is not more outlawed and hunted.” Since the Gestapo had fewer than twenty thousand agents, it relied on ordinary Germans to denounce their communist or Jewish neighbors as “enemies of the people.” Improving on initial SA efforts, the SS constructed three chief concentration camps (Konzentrationslager, or KZ) in Dachau, Buchenwald, and Sachsenhausen to contain the increasing number of those who might “endanger state security.”44 By discrimination, repression, and violence the Nazis created a countercommunity of political and racial victims in the KZ.

Those Germans who were not ostracized generally developed positive feelings about the Nazi project of a Volksgemeinschaft, since it contrasted with the divisiveness of the Weimar Republic. One important reason was the notable improvement of living conditions that made even workers consider the prewar years of the Third Reich as “a good time.” Another cause was the tangible benefit derived from some programs, which made the compulsion and indoctrination of the National Socialist organizations bearable. The 1936 Olympics in Berlin, which showcased Nazi accomplishments through new facilities like the one-hundred-thousand-spectator Olympiastadion and impressed even foreign visitors, were a case in point. In spite of the controversy over the barring of Jewish athletes and Jesse Owens’ spectacular victories, the Germans could point proudly to their winning a total of eighty-nine medals, which was considerably more than the fifty-six of their closest competitor, the United States.45 With such a mixture of control, incentive, and propaganda, Hitler succeeded in constructing a dictatorship of the right, resting largely on popular acclaim.

ANTIMODERN MODERNITY

The debate about the relationship between National Socialism and modernity remains sterile as long as it continues to be moralizing rather than analytical. By conflating progress with the advancement of democracy, western intellectuals have tended to denounce fascism as a reactionary “utopian antimodernism.” No doubt many pronouncements by Hitler, Rosenberg, and other National Socialist ideologues demonstrate that the Nazis rejected the Enlightenment heritage in its capitalist, democratic, and Soviet communist guise while railing against “modernist” culture. Yet when the adjective “modern” designates a historical period, then National Socialism clearly does belong to the recent era. And if one concedes with sociological theory that development involves “multiple modernities,” which include not only remnants of tradition but also rejections of some of its features, then the Nazi project can be understood as “proposing a radical alternative to liberal and socialist visions of what form modernity ideally should take.”46 Even if it may seem paradoxical, the National Socialists did develop their own version of modernity.

Hitler and his henchmen denounced the destructive consequences of democratic and Marxist modernization in the strongest terms. They hated democracy because it “produced an abortion of filth and fire,” had stabbed the German army in the back, accepted the humiliating Versailles Treaty, and sapped the nation’s strength by pacifism. Similarly they loathed the “Marxist world pest” as “spiritual degeneration” because Soviet Russia was ruled by “blood-stained criminals” who were “the dregs of humanity” and had “extirpated millions of educated people out of sheer blood lust.” The Nazis reserved their harshest invective for the common source of both rival ideologies: “the Jewish drive for world conquest” and “racial bastardization” that threatened the country by denationalizing it and polluting its blood.47 Such emphatic rejection of the western and Soviet rivals, however, called for the elaboration of a superior alternative that would not just escape into a mythical volkish past but revitalize the nation in the future. Designed to heal the wounds made by its competitors, this warped National Socialist vision might be called “organic modernity.”

Above all, the Nazi project of an alternative future sought to reconcile man with the machine in a creative union, redounding to national glory. For all his disparagement of experimental art, Hitler also used the adjective “modern” when talking positively about science and technology in the service of a revitalized nation.48 Making only halfhearted efforts to return the country to a rural past, the Nazi leadership was fascinated by novel machines such as radio transmitters, jet airplanes, and ballistic rockets and sponsored the first experiments with television. In spite of their anti-intellectualism, National Socialist leaders also supported research in weapons development for the sake of rearmament, racial science as basis for cleansing the national body, and volkish history in order to construct claims for expansionist foreign policy. In gigantic building projects like the canopy of the Tempelhof airport, Third Reich planners used “modern” techniques of steel and concrete construction while covering the facade with limestone. In designing the network of Autobahnen, they similarly tried to fit highways harmoniously into the landscape.49

A central aspect of organic modernity was the biopolitical effort to purify and strengthen the Volkskörper in a gigantic social-engineering project. This “biologization of the social” stemmed from the writings of physicians and culture critics who decried the nervousness, disease, degeneration, and declining birthrates attributed to the unhealthy lifestyle of the city. The Nazis embraced this international eugenic critique and pushed it in a racist direction by trying to combat negative tendencies such as inherited diseases through sterilization and prohibiting “inferior stock” such as asocial individuals and Jews from reproducing with Aryans. At the same time, they also sought to foster positive reproduction through programs like the SS Lebensborn, increasing marital and extramarital birthrates through incentives, reducing infant mortality, and curing venereal disease through improved preventive healthcare.50 Unconstrained by civil rights, such state intervention into individual sexuality, gender roles, and public health was a modern project of social medicalization, supported by academic research that acted in the name of racial purity and national strength.

Finally, the charismatic reshaping of German politics also aimed at providing a new and harmonious form of right-wing politics appropriate to the mass age. The Führer’s power rested not only on the propagation of the Hitler cult but also on a mystical willingness of a large part of the population to suspend criticism and accept his leadership. By “working toward the Führer,” the party acted as a crucial intermediary, since it interpreted his will and implemented his dictates, often even before they were announced. The state and its bureaucratic organs had no choice but to accept the direction of the Nazi Party and to play a subservient role. The individual citizen was compelled to trust the leader and, whenever called upon, applaud his decisions while trying to achieve the goals suggested by his superior wisdom. Prohibition of dissent and persecution of opposition were justified by eliminating the factionalism and squabbling of parliamentary debate. From Goebbels’ propaganda to Himmler’s SS henchmen, the structure and instruments of governance constituted a thoroughly modern consensus machine.51