REVOLT AGAINST MODERNITY

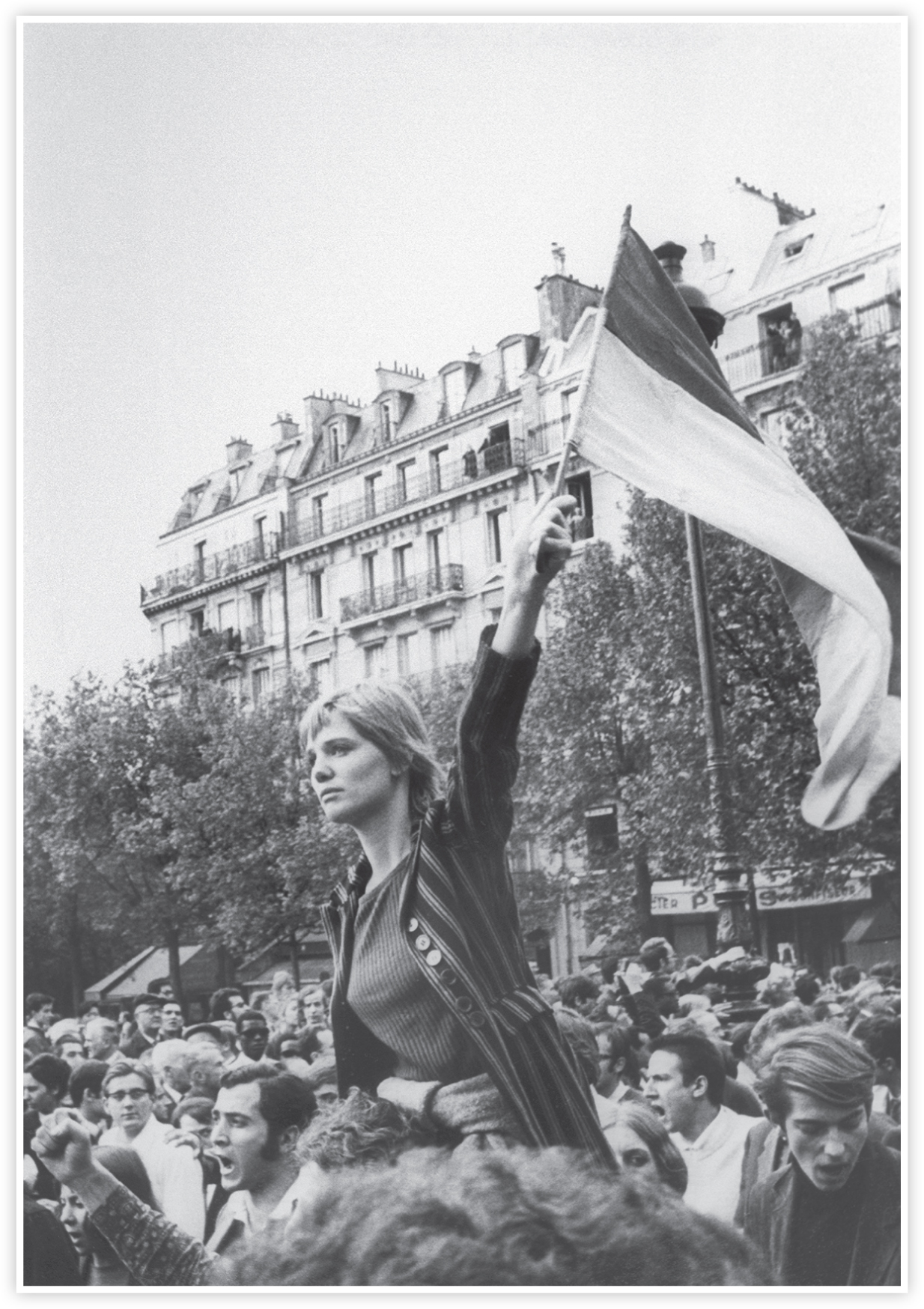

French student revolt, 1968. Source: Jean-Pierre Rey / Gamma-Rapho / Getty Images.

On February 18, 1973, three hundred demonstrators assembled near the village of Wyhl in southwestern Germany to protest against the construction of a nuclear reactor. The press conference they had called to explain their anger at having their objections ignored by the government quickly escalated into a heated exchange with the head of the building crew. Appalled that century-old trees were cut down, “the protestors broke through the fence and surged onto the site” of the future power plant. By climbing into bulldozers and jumping onto the shovels of excavators, the unruly crowd blocked further work and started arguing with the construction workers. But, having learned their techniques in a previous protest against the establishment of a lead factory in Marckolsheim on the French side of the Rhine, the demonstrators eventually calmed down, pitched tents, and got out the food and sleeping bags they had brought along for an extended vigil. Misrepresented by the press as nothing more than illegal interference, the site occupation was a spontaneous response to a growing confrontation that turned into a peaceful, well-disciplined protest using nonviolent methods of civil disobedience to stop the erection of a nuclear reactor promoted by a big power company.1

Such antinuclear protests were a delayed product of the grassroots mobilization inspired by the generational rebellion of 1968. This surprising youth revolt rejected the compromises of the older generation, which was willing to trade acquiescence in parliamentary politics for rising prosperity and personal comfort. A whole cluster of perceived injustices such as authoritarian paternalism, academic overcrowding, sexual repression, and imperialist war triggered the transnational protest wave. In strictly political terms the leftist attempt to incite a “new class” revolution of students and white-collar workers failed wherever it was attempted, but in cultural terms of changing lifestyles and values it was a smashing success.2 Ironically, in Eastern Europe the revolts in Poznań and the Prague Spring simultaneously sought to liberalize the one-party communist system with even less chance of victory. These efforts to create a more participatory democracy ironically proceeded at cross-purposes, since western protesters criticized the injustices of liberal modernity, while eastern dissidents rejected the repressiveness of its communist alternative.

Though these rebellions did not succeed politically, they triggered a series of new social movements during the early 1970s that eventually spread from the West to the East. In contrast to traditional labor-union agitation, these civil-society actions pursued a post–material prosperity agenda that tried to improve “the quality of life” rather than gain additional money. Growing out of local opposition to urban renewal, highway construction, or various intrusions on natural habitat, one such current was environmentalism, which campaigned for green spaces and ecological balance. Inspired by frustration with the insensitivity of male activists, another strand was the new feminism, which agitated for women’s rights and gender equality. Prompted by the nuclear-arms race and proliferation of intercontinental missiles, a final cause was the peace movement, which weaved religious, secular, and socialist threads into a pacifism that opposed the stationing of additional NATO rockets.3 Interestingly, this overlapping grassroots mobilization became increasingly critical of the negative consequences of industrial society and began to search for ways of transcending the constraints of high modernity.

The impact of the protest movements of the 1960s and 1970s is still disputed, because identity politics thereafter revolved around taking positions toward their aims and methods. Traumatized by Nazi excesses, conservatives and traditional liberals feared that the irrationalism of a mass movement would once again lead youths in a totalitarian direction. The Marxist rhetoric of some protests also suggested communist subversion, while the antiauthoritarian posturing implied a loss of civility and standards of achievement. In contrast, the youthful demonstrators of the New Left saw their revolt as Jürgen Habermas has described it: a “fundamental liberalization” of western society, a long-overdue effort to democratize parliamentary government. At the same time, they celebrated sexual liberation and changing values as necessary steps toward throwing off bourgeois constraints and embracing more permissive lifestyles. In the East the revival of civil society fed into dissident movements that eventually overthrew the communist regimes. Amplified and memorialized by media retrospectives during various anniversaries, the massive uprising of 1968 continues to cast a large shadow, since its aspirations and actions have been thoroughly mythologized by both opponents and supporters.4

By criticizing its practices and rejecting its values, the concurrent western and eastern revolts in effect repudiated the precepts of both democratic and socialist modernity. While the youth rebellion initially aimed to make life more humane, socially just, and peaceful, its neo-Marxist rhetoric, Maoist fashion, and turn toward violence signaled a rejection of liberal modernity by seeking to impose an unorthodox socialism on Western Europe. Ironically, the simultaneous unrest within the Soviet Bloc tried to humanize real existing socialism by recovering the bourgeois human rights and market incentives of that very rival version of modernity the western youth were rejecting. More successful in changing public priorities in the West were the new social movements that sought to escape the logic of the machine, male sexism, and the arms race. Finally, the reflections of postmodern theoreticians revealed a rising discontent with the rationalism, formalism, and inhumanity of mature industrial society. Taken together these diverse cultural currents expressed a search for a more humane form of politics beyond high modernity, a search that was to dominate the last quarter of the twentieth century.5

SOURCES OF PROTEST

In spite of rising prosperity and political freedom, some intellectuals had begun criticizing capitalist democracy, providing inspiration for the generational revolt of the late 1960s. One important impulse emanated from the British New Left, a loose cluster of intellectuals that sought to create a humane and liberal form of socialism, more radical than western social democracy and less Stalinist than Soviet communism. In their essays in the New Left Review, critics such as Perry Anderson and Edward P. Thomson strove for an unorthodox form of Marxism that probed cultural sources of alienation in consumer society according to the ideas of Antonio Gramsci. Revising the traditional concept of class conflict, they stressed that the shift to a service society made a new class of white-collar workers and students the revolutionary vanguard of the future. Theoreticians of the Frankfurt School like Herbert Marcuse also attempted to incorporate Sigmund Freud’s insights about the sexual repressiveness of bourgeois society.6 These debates produced an exciting mix of critiques that rejected the postwar restoration of liberal capitalism.

More colorful yet was the antiauthoritarian counterculture of various bohemian movements that also sought to reject the compromises inherent in bourgeois society. Inspired by Guy Debord, artists in France formed a group called Situationist International, which was intent on critically analyzing the situations of daily life in order to fulfill authentic individual desires. Vaguely Marxist in outlook, these situationists rejected modernist functionalism à la satellite city Sarcelles and strove to blend artistic creativity with personal freedom. The Dutch Provos followed similar impulses, seeking to provoke the established order by turning to drugs, sex, and rock ’n’ roll. Their manifesto attacked “capitalism, communism, fascism, bureaucracy, militarism, professionalism, dogmatism, and authoritarianism,” calling for “resistance wherever possible.” A motley collection of beatniks, vegetarians, pacifists, and artists, these antiauthoritarians often used humor to discredit the rules and norms they considered repressive. In contrast to the Marxist theoreticians of the New Left, the supporters of the counterculture represented a more anarchistic strain of rebellion.7

A final inspiration paradoxically came from the United States, since activists generally opposed its policy while adopting its protest methods. Popular culture styles such as wearing jeans and listening to rock music had already annoyed straitlaced bourgeois adults during the 1950s. More importantly, the nonviolent protest forms of the U.S. civil rights movement served as inspiration to European campus radicals trying to mobilize university students. Transmitted by a few key individuals, the provocations of the Free Speech Movement in Berkeley, California, quickly made their way to Berlin, while the cultural critique of the Frankfurt School was eagerly received in San Francisco. Joint opposition to the Vietnam War intensified this transatlantic exchange, since prominent antiwar songwriter/singers like Joan Baez performed at mass rallies on the continent. Photogenic icons of the Black Power movement such as Angela Davis were popular on both sides of the Iron Curtain. Borrowing protest methods and popular culture from the United States, student radicals rejected the Vietnam War and called for a “second front” of anti-imperialist solidarity.8

Beyond such inspirations, the youth revolt also stemmed from a series of concrete irritations such as the prevailing authoritarianism that complicated the passage through adolescence. In most families fathers were still firmly in control, and superiors in institutions set rules that were expected to be observed, while youths craved more personal freedom. This paternalistic order enforced middle-class virtues such as punctuality, cleanliness, and hard work—much of which seemed increasingly onerous to rebellious adolescents. Still subject to memories of deprivation during the war, most adults were proud of visible signs of material prosperity such as houses, cars, and washing machines, while the young who had grown up in increasing affluence took such possessions for granted and sought other, postmaterial meanings in life. In Germany, Italy, and their former allies and occupied countries, authority figures were discredited by having collaborated with Nazis, provoking awkward silences to the question “Daddy, what did you do during the war?” The young therefore embraced the slogan “Trust no one over thirty.”9

Frustration with overcrowding in schools and personal alienation from mass universities were additional motives of protest. The enormous expansion of secondary education had produced a tidal wave of graduates that made university lecture halls and seminars overflow with students, since construction and personnel had not been able to keep up. Many new institutions like Nanterre and Bielefeld were built in modernist styles of glass, steel, and concrete, resembling factory halls in their sterile impersonality. An increasing number of students also stemmed from underprivileged backgrounds without experience of academic culture and therefore felt intellectually overtaxed and socially foreign in their unaccustomed surroundings. At the same time, the traditional teaching practices of the universities were slow to adapt, with the chaired professors remaining all-powerful and their didactic styles rooted in monotone lectures. Denouncing the “musty smell of a thousand years under the academic gowns,” radical students therefore had ample reason to feel like an academic proletariat.10

Yet another impulse was the attempt to end the sexual repression that characterized the moralism of restored bourgeois society. Youths resented the fraudulence of the “double standard,” which allowed successful men to have mistresses while demanding absolute fidelity of their wives. At the same time they opposed the lack of information about birth control, the prohibition of abortion, and the legal prosecution of homosexuals as outmoded. For the first time in history, the introduction of the “pill” made it possible to have intercourse without having to fear the consequences of unwanted pregnancy. The availability of effective oral contraception fundamentally shifted the alleged purpose of sex away from procreation and toward recreation. Gradually, religious teachings lost their force among a generation eager to explore their bodies and to experiment freely with sexual pleasure—a shift of attitudes also supported by progressive media. The new practice of living in communes or just sharing apartments also provided more opportunities for having sex. As a result, sexual liberation became part of the generational revolt, politicizing private desire.11

Mounting opposition to the U.S. intervention in the civil war between North and South Vietnam was a final spur to rebellion. Since most youths were ignorant of the complexities of national liberation struggles against European colonialism, the presence of international students from the Third World created anti-imperialist solidarity on European campuses. This was the first war to be carried live on TV, in which the evening news tended to show shocking images of devastation from U.S. bombing and chemical warfare that killed civilians and destroyed farms and villages. It did not help that the South Vietnamese regime was considered a military dictatorship, mired in corruption—hardly a beacon of the so-called free world. Moreover, none of the brutality of the communist-supported Vietcong appeared on the screens, since journalists were reluctant to navigate booby-trapped trails or crawl through supply tunnels in order to report on the violence of these presumed liberators of the nation. By seeming to betray its own ideals through the “slaughter of the civilian population,” American policy discredited itself and broke the Cold War framing of the moral superiority of the West.12

Inspired by a mix of neo-Marxist, anarchist, and civil rights examples, the charismatic German student leader Rudi Dutschke embodied many central facets of the protest movement. Born in East Germany, he left the GDR just before the Berlin escape route was closed because he found the repression of “real existing socialism” unbearable. Married to Gretchen Klotz, a devoutly religious American exchange student, he was in touch with radical currents in the United States. Chafing at western duplicity, he was drawn to anarchistic forms of lifestyle rebellion. But as a graduate student of sociology, he tried to construct a new social theory that might explain the contradictions of mature capitalism. Ideologically, he was looking for a truly democratic form of socialism that would provide peace, freedom, and equality. In mass rallies this combination of theoretical grounding and emotional commitment made him an inspiring speaker, adored by youthful crowds. As symbolic leader of the German student movement he rejected both communist modernization and liberal consumer modernity, looking for a revolution that would create a more just form of progressive politics.13

PATTERNS OF REVOLT

The protest movements spread quickly in part because their novel methods confused the authorities and intrigued potential followers. Unlike conventional street demonstrations of the labor movement, sit-ins blocked the normal functioning of educational and governmental institutions, sometimes for weeks, while teach-ins subverted regular instruction by spreading radical messages. This civil disobedience worked with calculated rule violations, designed to incense the establishment by making it difficult to counter them with legal means since they remained nonviolent. It was especially the irreverence of slogans like “by day they are cops, at night they are flops” as well as the innovative design of placards, such as one with the picture of the Shah of Iran on a wanted poster for murder, that drew attention.14 These tactics baffled the authorities because public officials would look repressive if they retaliated but might appear incompetent if they just let the protests pass. Many activists considered poking fun at the professoriate or the police as an exciting game in which they gained new adherents by outwitting their opponents.

In due course the protesters learned to evoke sympathy from by- standers and intellectuals through appearing as victims of clumsy repression. They carefully planned their provocations so as to achieve notoriety and unmask the oppressive nature of state power. When frustrated policemen beat peaceful students with billy clubs, dragging them bodily into paddy wagons, it looked as if the state were initiating violence to suppress dissent. Even if their headlines condemned the demonstrators, the media descriptions and photographs of police actions seemed to bear out accusations of the political intolerance of parliamentary democracy. The activists became quite adept at not only establishing a public sphere of their own through leaflets, counterculture newspapers, and so on, but also at using the TV images and newspaper editorials of the establishment for their cause. Reported in dramatic detail, each official repression created new converts to the cause. By the spring of 1968, the growing following on campuses inspired leaders like Daniel Cohn-Bendit and Rudi Dutschke to think about the feasibility of a “revolutionary seizure of power.”15

In West Germany, two reactionary acts of violence speeded the gradual buildup of protest by arousing mass support. The initial campus confrontations over free-speech issues gained only local notice, though the campaign against the controversial emergency laws, which reduced citizens’ rights during natural or civil emergencies, drew church and union support. But when the police officer Karl-Heinz Kurras shot bystander Benno Ohnesorg on June 2, 1967, during an antishah demonstration, shocked students organized sympathy demonstrations in other cities, while intellectuals like Heinrich Böll denounced the repressiveness of the state. Claiming that “the postfascist system in the Federal Government has become a pre-fascist one,” the Socialist German Student League (SDS) called for attacks on the capitalist oligarchy. The international Vietnam Congress in February 1968 radicalized its message to fighting “imperialism in its metropolitan centers.” When on April 11 the neo-Nazi Josef Bachmann shot Rudi Dutschke, students stormed the offices of the rightwing Springer tabloid Bild, which had incited antistudent violence. But just when activists thought that the movement was becoming irresistible, it started to fizzle.16

In France student activists came closer to seizing power when they resumed the tradition of nineteenth-century revolutions by erecting barricades in the Quartier Latin. In the early 1960s the national student union UNEF had begun to criticize the war in Algeria, while half a decade later it protested against the technocratic restructuring of the universities. Led by “Danny the Red” Cohn-Bendit, activists gathered in Nanterre in March 1968 and moved on to the Sorbonne in late April. When the police brutally evicted them in early May, the students, encouraged by public sympathy, defended the university with cobblestone barricades, following the ironic slogan: “The beach lies under the pavement.” For several days the students and the police fought pitched battles. On May 13 about ten million laborers staged a wildcat general strike, demanding autogestion (workers’ control of the factories). The government seemed ready to fall when the frightened president Charles de Gaulle flew to a military base in Germany. But after Prime Minister Georges Pompidou offered Renault laborers wage increases, the excitement passed.17

Only in Italy did the confrontation assume a similar intensity, while in Britain and the smaller West European countries the conflict remained more moderate. Starting with the occupation of universities in 1967, Italian students became quite radical in denouncing academic authoritarianism, calling for potere studentesco. In May 1968 the revolt turned violent when the police brutally repressed protests at the Villa Giulia in Rome. The activists were supported by leftist workers who were clamoring for control of their industries, initiating a decade of violence that culminated in the terrorism of the Red Brigades. In contrast, the demonstrations in British universities remained generally peaceful, even though the activists were making similar demands for liberalizing the academy and opposing the war in Vietnam. While Belgian students polarized into Flemish and French speakers, in the Netherlands they followed the German example of creating “critical universities” that attacked capitalist democracy intellectually rather than physically. The fervor infected even Scandinavia, but here the debates also remained relatively civil.18

Much to the surprise of the activists, the generational revolt collapsed almost as rapidly as it had begun. One key reason was the weakness of neo-Marxist class-struggle theory, since white-collar employees and university graduates, supposedly the new proletariat, were ultimately more interested in achieving a bourgeois lifestyle than in overthrowing the social order. In spite of the popularity of iconic revolutionary heroes like the ubiquitously placarded Che Guevara, it proved quite difficult to transfer Maoist-inspired urban guerrilla tactics to the European metropole. The majority of the continental working class refused to join forces with the disgruntled intellectuals because it already had too much to lose as a result of rising prosperity. Moreover, the accusation of neofascism that radical protesters hurled against the elite was clearly an exaggeration, since parliamentary democracy responded by not just reelecting President de Gaulle in France but also creating a progressive social-liberal coalition led by Willy Brandt in Germany. When their revolutionary fervor cooled, most youths were willing to embark instead on “the long march through the institutions” in order to reform them from within.19

The failure to seize power fragmented and radicalized the student movement. Much protest energy focused on making the existing system more responsive by democratizing it from below. During the struggle many activists also figured out that in order to transform the world, “we had to change ourselves” by embracing an antiauthoritarian lifestyle of informal dress and libertine sex. But an incorrigible minority of Marxist theoreticians splintered into competing Trotskyite, Maoist, or Stalinist sects, combating each other rather than fighting capitalism. A few hard-core radicals in the German Red Army Faction and the Italian Red Brigades progressed from “violence against things” to violence against persons, waging a terrorist war against government and business that cost dozens of lives. Dispelling the protest movement’s initial romantic appeal, the collateral damage of innocent blood shed for “the revolution” turned even supportive intellectuals against this ideological crusade. The militant self-defense of democracy in Italy and the resolute German response to an airplane hijacking in the autumn of 1977 reduced terrorism to irrelevance.20

By narrowing into Maoist dogmatism, the splinter groups’ search for a socialist humanism led to a dead end that sought to substitute the Marxist alternative for liberal modernity. Rejecting technocratic modernization, one former activist recalled that he “would not want to lead a life anymore where you would just function for the machine, and the machine would be so heinous that you would decide this machine had to be stopped.”21 This understandable critique led many activists to choose a cure that turned out worse than the disease—the Maoist prescription for modernizing the Third World. The “little red book” of Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-Tung could only become popular among some western intellectuals because of their profound ignorance of the Cultural Revolution taking place in China at the same time. Killing millions of innocent citizens, this campaign to speed the ideological transformation of China and enforce a Chairman Mao–approved lifestyle abused youthful idealism so as to destroy many ancient cultural traditions. No wonder the effort to replace liberal democracy with its Maoist alternative was doomed to failure: its prescriptions were inappropriate for Western Europe.

SOCIALISM WITH A HUMAN FACE

While the protest movement gathered steam in the West, popular discontent was also building up in the Eastern Bloc under the surface of dictatorial control, hoping to reform socialism. With the help of Soviet army and secret service intimidation, the local communist parties had generally succeeded in stamping out any open anticommunist opposition by the late 1950s. But workers were becoming increasingly disgruntled when they realized that the planned economy was causing their living standards to fall behind those of their cousins on the other side of the Iron Curtain. Writers and painters too, frustrated by the simplemindedness of the proletarian literary and artistic styles mandated by the leadership, chafed at the heavy hand of censorship, wanting more freedom to experiment. Even genuine supporters of Marxism among the intellectuals resented the Stalinist remnants of communist politics and longed for a more democratic form of socialism.22 While the Soviet military interventions in 1953 and 1956 served as a deterrent against open dissent, pressures were building in Eastern Europe that sought a sudden release.

The first rumblings of protest occurred in Poland, directed against the regime of Władysław Gomułka, who steered a zigzag course between Soviet control and national independence. In contrast to its subjugation in other East European countries, the Catholic Church in Poland remained a public force, as did dissidents like oftimprisoned Jacek Kuroń, who courageously published his criticism abroad. Moreover, the failing economy, concentrated in heavy industry, disappointed the workers, who demanded better living conditions. After the banning of a patriotic play by Adam Mickiewicz, students protested in Warsaw in March 1968. The brutal repression of the demonstration by riot police spread their strike to other universities where it was again harshly subdued, with 2,725 participants, including the dissident Adam Michnik, arrested. Shifting the blame, Minister of Interior Mieczysław Moczar accused “hidden Zionists” of being responsible for the unrest. Moreover, he created a card file of Jews and expelled them from the party, subsequently prompting more than fifteen thousand members of the Jewish community to emigrate.23 Though the regime reasserted control with this campaign of hate, new waves of protests broke out in Poland during the following years.

The rise of dissatisfaction in Czechoslovakia was more surprising, because that country had welcomed liberation by the Red Army and possessed a large Communist Party. Nonetheless the slowness of de-Stalinization irritated many citizens who remembered Stalin’s anticosmopolitan trials. The stalling of the already highly developed economy due to inappropriate smokestack-industrialization plans also frustrated consumers, who had hoped that the reintroduction of incentives by Ota Šik during the mid-1960s would restore growth. At the same time talented writers like Václav Havel, Ivan Klima, and Milan Kundera rebelled against the tightness of censorship that stifled their creativity. Moreover, tensions between the Czech and the Slovak halves of the state were rising, since the latter felt neglected in economic planning. As a result of these pressures, the flexible Slovak party chief Alexander Dubček replaced the orthodox Antonin Novotny in January 1968. Hinting at his willingness to initiate changes, the new leader proposed building “a socialism that corresponds to the historical democratic traditions of Czechoslovakia.”24

In April Dubček announced an even more extensive Action Program of reforms that became known by its symbolic name as “socialism with a human face.” Arguing that the period of forceful class struggle was over, it promised a reorientation to a consumer economy, directed by capable experts, as well as freedom of speech and the press, and of individual movement in order to support the revitalization. Though the Communist Party (KPC) intended to lead the reforms, they quickly developed an unstoppable momentum of their own. When censorship was lifted, the author Ludvík Vaculík published a manifesto titled “The Two Thousand Words,” which called on the people to take the initiative in pushing for further changes. As a result of the increasing freedom, the media also started to expose the corruption of the Communist Party. At the same time, some moderate socialists revived an independent Social Democratic Party. In the heady spring days of Prague, anything seemed possible—even the democratization of communism from within.25

Increasingly concerned about the KPC’s loss of control, Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev finally decided to stop the liberalization with military intervention by Warsaw Pact troops. During a March meeting in Dresden, Dubček still managed to reassure his colleagues that he was just trying to put communism on a firmer foundation. But the unpopular leaders Walter Ulbricht of the GDR, Władysław Gomułka of Poland, and Janós Kádár of Hungary were afraid that demands for liberalization would spill across their borders. During the August Warsaw Pact conference in Bratislava, the Czech reformers no longer succeeded in dispelling such worries. When a conservative minority in the Prague Politburo called for Soviet assistance against an alleged counterrevolution, Brezhnev ordered an invasion to halt the dismantling of communism. On the night of August 20, 1968, two hundred thousand Warsaw Pact troops with two thousand tanks invaded Czechoslovakia, encountering only token opposition. Seventy-two Czechs were killed and seven hundred others wounded in the struggle.26 Passive resistance was unable to prevent this suppression of the daring experiment.

Gradually, but all the more effectively, orthodox communism regained control over Czechoslovakia, condemning it to torpor for another twenty-one years. Verbal protests by western countries and some neutrals were of little avail, and a critical UN resolution was blocked by a Soviet veto. Even the dramatic self-immolation of Jan Palach on Wenceslas Square could not halt the ouster of Dubček and the appointment of Gustav Husák. The new Czech leader pursued a “normalization policy” that rolled back the economic reforms, tightened party control, and reinstituted a harsh form of censorship. Outwardly the cowed citizenry had no choice but to comply, but inwardly many continued to resent the Soviet-led invasion. Husák tried to stifle the criticism by improving living standards, that is, providing more consumer goods and more distracting TV entertainment. But the heavy hand of the censor drove dissident intellectuals underground, forcing them to engage in a form of “antipolitics” that refrained from open challenge and yet tried to reconstitute an independent civil society.27

The suppression of the Prague Spring had a profound effect, since it ended the utopian appeal of communism for intellectuals on both sides of the Iron Curtain. Within the Soviet Bloc, the Soviet army’s invasion dashed hopes for a communist self-reform that would shed at least its Stalinist if not Leninist guise to arrive at a more democratic version. The armed intervention of the Warsaw Pact powers revealed that Soviet rule over Eastern Europe was a form of Russian imperialism, propping up minority dictatorships in the client states. Moreover, the use of force to squash dissent also shocked members of the West European communist parties who had seen the Soviet Union as a beacon of progress, strengthening their Eurocommunist impulses to find a more moderate and independent path toward socialism. At the same time the failure of the Czech experiment also disillusioned myopic western fellow travelers of communism like Jean-Paul Sartre by pointing out that Moscow’s rhetoric of peace and equality was a sham. In global terms, the Soviets suddenly looked conservative in contrast to revolutionary Maoism.28

Another result of the invasion of Czechoslovakia was the discrediting of the Soviet version of modernization, since it rested on compulsion rather than voluntary cooperation. Especially for those countries that possessed a developed consumer economy, the heavy industrialization mandated by the Soviet Union proved counterproductive, since it did not lead them forward. The communist claim of superior social welfare lost its luster in a dictatorship where basic freedoms did not exist. Political repression made western human rights once again relevant for intellectuals and citizens in the East, although such bourgeois liberties were supposed to have been superseded by the building of socialism. In 1968 European intellectuals therefore pursued two rather contradictory agendas for transcending high modernity: while western radicals dreamed of some kind of socialist revolution to end capitalist exploitation and imperialist aggression, eastern dissidents rediscovered civil rights as a necessary guarantee of their freedom of expression.29 These cross-purposes inhibited communication across the Iron Curtain, creating an unresolved tension until 1989.

NEW SOCIAL MOVEMENTS

The new social movements that arose from the debris left behind by the generational revolt moved away from high modernity, since they pursued a fundamentally different vision. Dispirited and disorganized, the European Left gradually distanced itself from the dead end of neo-Marxist sectarianism and the counterproductive cult of terrorist violence. Surprised by the intensity of local protests against urban renewal, highway construction, and nuclear power, various activists quickly recognized their mobilizing potential. Civic conflict offered a new brand of open-ended grassroots politics, addressing single issues like environmental protection, gender equality, or international peace that created a movement identity for participants. In contrast to the tight organization and material aims of the labor movement, these contestations were loosely organized and pursued a postmaterialistic quality-of-life agenda, which reflected the value shift of the generational revolt. Their young and well-educated members wanted to regain control of their lives, rejecting the domination of the machine, the corporation, and the state.30

The novel form of “citizens’ initiatives” arose spontaneously as a result of local confrontations over often mundane issues affecting urban neighborhoods. For instance, when city planners wanted to build a feeder road through Hamburg’s working-class district of Ottensen, its inhabitants rebelled because the highway would cut their quarter in two. They protested vociferously against the decision of their elected officials, signing petitions, holding rallies, drawing up posters, and distributing leaflets. To coordinate the plethora of initiatives, the protesters eventually formed an Action Community network in order to negotiate with the city authorities. Expecting passive acquiescence to their efforts to make Hamburg more car friendly, officials were eventually forced to abandon their plans and instead find ways to renovate the dilapidated buildings of the quarter.31 Multiplied dozens of times in different European cities, such instances of mobilization from below created a new kind of politics outside parliamentary channels that proved surprisingly successful.

A key issue that inspired widespread protests was the deterioration of the environment due to unchecked economic growth. In industrial areas like the Ruhr Basin, uncontrolled factory effluents had made the water undrinkable, while in the chemical triangle of East Germany the air had grown so foul as to cause allergic coughs in children. In Czech forests acid rain was killing woods on exposed hillsides, initiating a Waldsterben (forest dieback) that left spindly skeletons of trees, ruining forestry. At the same time the factory-farming of animals and the use of pesticides in fields contaminated Dutch soil, killing all manner of birds and small animals. Moreover, accidents in nuclear plants like the Ukrainian Chernobyl explosion in 1986 threatened to poison whole areas for generations. Responding to personal concerns and dramatic media reports, traditional nature groups transformed themselves into organizations for environmental protection. Their constant warnings gradually changed the political climate from pro–industrial expansion to ecological sensitivity, making political parties adopt this issue in their platforms.32

Another important cause was gender equality, which inspired a new feminism that sought to overthrow patriarchy and lighten the double burden of managing a household and career work. As a result of socialist egalitarianism and communist planning that increased the need for labor, East European women had many formal rights, though obtaining daily provisions remained difficult. In the West it was resentment of male activists’ insensitivity that in 1968 inspired Helke Sander to fight against “the social oppression of women” by calling on them “to emancipate themselves.” Concretely that meant legalizing abortion, a demand voiced by several hundred French women who confessed publicly that they had ignored its prohibition. Another related issue was the easing of divorce laws to allow the dissolution of broken marriages without attributing legal fault to either party. Female professionals also chafed at the “glass ceiling” that kept pay unequal and denied chances for promotion. As a result of such frustration a new women’s movement evolved that campaigned for turning the abstract principle of equality into equal chances of social citizenship.33

A final problem that mobilized a broad-based following was the preservation of peace during the nuclear confrontation of the Cold War. Pacifist engagement was complicated by communist propaganda that styled the Soviet Bloc as the “camp of peace” in spite of its militarization. Moreover, earlier campaign of the 1950s against West German rearmament and the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament in Britain, spearheaded by Bertrand Russell, had failed. But the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and the NATO dual-track decision in 1979, which pursued, simultaneously, nuclear-arms reduction talks and a buildup of nuclear-armed missiles, gave the issue a renewed urgency. Supported by churches, trade unions, and prominent intellectuals, a widespread protest movement “reject[ed] the arms buildup that would turn Central Europe into a nuclear weapons platform for the United States” and demanded that no intermediate-range missiles be stationed there. In London, Bonn, and all over Western Europe three million people demonstrated between 1981 and 1983 for “a nuclear-free Europe.” But after the FRG parliament voted for the missiles and they were deployed, the movement collapsed.34

By the late 1970s some of these different groups—environmentalists, feminists, antiwar activists, and so on—started to combine their political efforts under the banner of new parliamentary parties, known according to the dominant issue as the Greens. Ecology parties scored the first successes in Britain and Belgium. In West Germany it took until 1979 for a loose alliance, led by the charismatic Petra Kelly, to win 3.2 percent of the vote in an election for the European Parliament, enough to give it public funding. Its founding program of 1980 declared the West German Greens to be an “alternative to the traditional parties” aiming at “four principles, which can be described as: ecological, social, grassroots democratic, and nonviolent.” In the election of 1983 the party won 5.6 percent and thereby entered the Bundestag, and two years later Joschka Fischer became the first Green Hessian cabinet member, wearing jeans and sneakers in symbolic protest against the establishment. Split between fundamentalists who wanted radical change and realists who were willing to work within parliament, the Greens offered a different style as “antiparty” and attracted a young and educated clientele. Eventually Green parties also formed in other countries but had less electoral success.35

Owing to the dictatorial control of public space, new social movements developed in Eastern Europe somewhat later and with greater difficulty. But some of the concerns about the environment, sexism, and militarism were similar, because western media penetration of the Iron Curtain provided information on issues and examples of organization, while visits offered direct personal encouragement. The gradual reemergence of civil society and underground publication allowed the formation of an ecology club in Poland that dared criticize the government’s industrial policy. In the GDR it was the peace movement that appropriated official propaganda for its own ends, coining the slogan “swords into plowshares” to protest the militarization of East German society. The Protestant Church offered a quasi-public sphere in which critical groups could meet, discuss women’s issues, and exchange ideas in homemade publications like the Umweltblätter. As a result of secret service repression, these groups realized the importance of human rights and became part of the civil opposition to communism.36

Though the new social movements were an outgrowth of modernity, they increasingly came to reject some of its central tenets. Their often inchoate protest opposed the unlimited extension of highly industrial society, since they considered the environmental, gendered, and military consequences deleterious. Ever since the Club of Rome’s alarming study of The Limits to Growth in 1972, western critics denounced the gospel of economic expansion shared by both employers and employees. In the East, dissidents also rejected the productivist ideology of planning that ignored the social and ecological impacts of exploiting natural resources. In order to make their voices heard, these activists engaged in grassroots organization, demanding more participatory democracy. Their counterimage was of an ecologically sensitive, gender-equal, and peaceful world in harmony with itself and therefore sustainable for the future. The German sociologist Claus Offe claimed that this was “a ‘modern’ critique of further modernization.”37 But by trying to correct the mistakes of industrialization, the new social movements sought to leave both capitalist and communist modernity behind.

POSTMODERN CRITIQUE

Ironically, the most radical opposition to modernism arose from within modernity itself as a set of multiple discontents with its cultural forms and scientific worldview. In architecture it referred to a rejection of the bland functionalism of the International Style, dominant in city planning and urban renewal. In literary criticism it represented an appreciation of creative works beyond the classic modernism of T. S. Eliot as well as an opening to the study of popular culture. In the social sciences it consisted of a turn away from the grand modernization narratives and an acknowledgement of the negative aspects of development. And in philosophy it involved a subjectivist critique of traditional rationalism by exploring the implications of the “linguistic turn.” When trying to leave modernism behind, artists and thinkers increasingly embraced Arnold Toynbee’s concept of the “postmodern age” during the 1970s.38 As a relational term, designating an era after high industrialism, the label postmodernism represented a diffuse mood rather than a coherent program, raising the question of whether the historic era of modernity might not have come to an end.

One impetus of the assault on high modernity came from architects who rejected the rationalist functionalism of the Bauhaus style. Since glass, steel, and concrete skyscrapers looked alike everywhere, architecture critics like Robert Venturi began to denounce them as boring, essentially a repetition of the same pattern irrespective of climate or landscape. Moreover, the negative results of city planning in traffic noise, air pollution, and individual anomie led to a disenchantment with the architectural pretension of curing social problems through building design or urban renewal. Breaking the modernist mold led to a liberating sense of experimentation, which allowed a plurality of styles, recovered the delight in decoration, and borrowed freely from preceding epochs. The transition from the industrial shape of the Centre Pompidou in Paris via James Stirling’s playful use of technology in the Neue Staatsgalerie in Stuttgart to the soaring vision of Frank Gehring’s Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao exemplifies this trajectory. The resulting newfound freedom of design made architecture interesting again.39

Another attack on the modernist synthesis came from the linguistic turn, which emphasized the centrality of language for human understanding. Going beyond structuralist semiotics, the French philosopher Jacques Derrida developed a method of “deconstruction” that implied a close reading of the text for its ideological underpinnings, hidden subtexts, and covert messages, not accessible on the surface. This approach contrasted sharply with literary history, which focused on the intention of an author, and with Marxist probing of the social context of a work. Instead, a deconstructive reading focused on a given text itself, analyzing its stylistic traits and multiple layers of meaning. Moreover, Derrida also proclaimed the axiom that “there is no such thing as outside-of-the-text,” denying that texts could refer to something called “reality,” because all references to an outside world had to be expressed by words. This radical questioning opened the way to a multiplicity of imaginative readings but at the same time undercut the possibility of objective cognition, a central tenet of scientific modernity.40

Yet another French theorist, Jean-Francois Lyotard, attempted to spell out the implications of this linguistic approach in his reflections on the “postmodern condition,” published as a book bearing that title in 1979. Disillusioned with Marxist politics and with Freudian psychoanalysis, he also rejected the Enlightenment heritage of faith in human progress. Afraid of the reduction of human knowledge to mere “data” as a result of the introduction of computers, he counseled a fundamental incredulity against “meta-narratives,” which attempt to explain and justify human development, because he believed these usually justified some kind of suppression of others. Such a radical critique only left “language games,” though even these were to be treated with suspicion.41 But instead of despairing, Lyotard enjoyed the newfound freedom of the artistic avant-garde, supporting experimentation with appreciative reviews. This deconstruction of grand narratives came to be especially important for historians, because it provided them with a tool to dispute the claims of nationalist, proletarian, or religious mythologizing.

Michel Foucault, whose colorful life inspired a set of eclectic political commitments and philosophical stances, was an even more controversial critic of modernity. Like his contemporaries, he gradually emancipated himself from the rationalist legacy of Marxism though he remained active in various leftist causes such as decolonization and the antipsychiatry movement. In his sprawling works, he attempted nothing less than an “archaeology of knowledge,” wrestling with the development of the whole philosophical tradition from Kant onward. Owing to the medical background of his parents, his first books dealt with disease, madness, and civilization, revealing the social construction of illness and sanity. Since being gay was still looked down upon in France, he fearlessly explored the history of sexuality. Moreover, as a moralist he reflected on the importance of power, through “governmentality” and routines of discipline and punishment. But his most important contribution was the concept of “discourse” as an interrelated rhetorical system of talking about certain topics and as a way of justifying certain policies.42

In part, this postmodern onslaught, amplified by the media, had a liberating effect, since it created space for innovation. In architecture, painting, and music artists felt free to ignore the conventions of high modernism, experimenting with even more radical styles. In literature the emphasis on deconstruction encouraged a proliferation of close readings that were no longer limited by canonic authority. In the media the postmodern eye recovered a multitude of photographic and filmic images regardless of their provenance or temporality. In philosophy this perspective undercut claims to objective knowledge, allowing for greater play of subjectivities. In the social sciences such a critique helped undermine linear notions of modernization as a progressive development according to the liberal capitalist or Marxist model. In history the attack on the grand narratives allowed the emergence of counterstories of previously suppressed minorities.43 Especially feminist, black, and postcolonial thinkers in cultural studies embraced postmodernism in order to overthrow the hegemony of dead, white, European males.

Postmodernism, nonetheless, evoked widespread criticism that denounced it as a mere intellectual fashion, incapable of making a substantial contribution to illuminating the human condition. Especially conservative and religious thinkers castigated the moral relativism of a perspective in which “anything goes.” At the same time Marxists in the East and West attacked the postmoderns as representatives of a decadent “late capitalism” who were unwilling to engage the massive injustices of the world. While natural scientists simply ignored the “pomo” talk, most social scientists also rejected its culturalist epistemology in favor of generalizations derived from quantitative data and rational-choice theory. The most serious challenge came, however, from liberal theorists like the sociologist Jürgen Habermas who attempted to rescue the emancipatory potential of the Enlightenment by establishing a method of discursive rationality.44 While in France and the United States postmodern theories held sway, German intellectuals continued to cling to modernity as a progressive and democratic antidote to the reactionary spirit of National Socialism.

The postmodern attack on high modernity was therefore stronger in signaling that an epoch was coming to an end than in defining the character of what might come thereafter. What the self-proclaimed rebels rejected was quite clear—they disliked rationality, functionalism, objectivity, Marxism, and capitalism. In spite of distancing themselves from the ideology of modernization, they remained largely committed to causes of the Left. But the theoreticians were too confused, their philosophical arguments too arcane, and their claims too exaggerated to be entirely convincing. If human rights were not universally valid, what were the grounds on which opposition to patriarchy, racism, or imperialism could be based? Yet postmodernism spread rapidly through intellectual circles not just because it was hyped by the media, forever in search of novelty. In many ways the linguistic theorists touched a cultural nerve, signaling that something was ending without really knowing what that implied for the future. In that sense, postmodernism was both the end of high modernity and a prologue for things to come.

AFTER MODERNITY?

In many ways the postmodern provocation, proclaiming the end of modernity, seemed as preposterous to contemporary progressives as to cultural traditionalists. Skeptics could adduce many arguments that the term modernity, according to its various meanings, continued to be a valid description of the last quarter of the twentieth century. Certainly as a grand epoch, modern history, starting at the Renaissance and the Reformation, had not ended just because some French theorists and American literary critics were making such a grandiose pronouncement. At the same time the adjectival usage of the concept modern as continually new suggested an eternal present that would go on forever, though always changing its content. Finally, optimistic interpretations of modernization as a process that brought progress could be sustained for Europe by pointing to the improvement of numerous indicators such as personal wealth or life expectancy.45 Although there were ample reasons not to believe that the present had entered an era “after modernity,” the claim to postmodernity, nonetheless, enjoyed widespread resonance.

One source of postmodernism’s popularity was the undoubted existence of a cultural movement that described itself as such. Dominant in the new playfulness of architecture, it extended to other fields like music and literature as well. Moreover, the impact of the linguistic and later iconic turns created a new form of literary and artistic criticism, interpreting these works for the general public. Of course, in many ways the postmoderns simply carried the experimentation of the avant-garde further, selectively advancing or leaving behind modernist forms. Since what was continued or rejected depended on the definition of high modernity in each respective field, no unified postmodern style did emerge. Instead postmodernism became defined as repudiation of the existing canon, giving voice and image to a plurality of approaches, freely mixing present with past, and ignoring the distinction between high and popular culture. This fragmentation proved at the same time advantageous and limiting, but it was justified by a cultural politics that rebelled against standards by stressing the creative power of diversity.46

Another cause of the rapid spread of the term was the “value change” to postmaterialism resulting from the generational rebellion of the 1960s. Almost immediately survey researchers like Ronald Inglehart discovered a shift from the postwar generation’s pursuit of prosperity and security to their children’s emphasis on quality of life and self-realization. Well-educated urban professionals, especially, set priorities that differed from those of the labor-union struggles over wages and working conditions by campaigning against environmental degradation, male patriarchy, or the arms race. Interestingly enough, their critique turned against both capitalist exploitation and socialist regimentation, since it rejected the continuation of economic growth and emphasized sustainability instead. In contrast to large-scale industry, big organizations, and government bureaucracy, the new social movements preferred small crafts, informal networks, and grassroots mobilization.47 No doubt there was a romantic element in the rejection of high modernity, but the search for alternatives was also a constructive corrective to its shortcomings.

A final source of the postmodern rhetoric was the erosion of the modernization paradigm, both as a macro-sociological theory of human evolution and as a strategy of economic development. Since the benefits of modernity seemed self-evident because of improving living standards during the postwar boom, the social-science debate had revolved around how to advance the process more quickly and spread it to the so-called developing countries. But modernization lost its luster for theoretical as well as practical reasons: To begin with, the philosophical assault of the postmodern theorists undercut the epistemological foundations on which its social-science generalizations were based. Moreover, the results of capitalist and communist strategies of development in the decolonizing countries turned out to be rather disappointing. While the West successfully shifted to a consumer economy, the Soviet Bloc fell behind, discrediting its socialist alternative in the eyes of its own citizens. Finally, the growing sensitivity toward genocide, triggered by the growing awareness of the Holocaust, also robbed modernity of its emancipatory nimbus by revealing its dark underside.48

The question of whether modernity has passed has yet to find a definitive answer. Many arguments speak for a continuation of high modernity, since science and technology, industrial production, bureaucratic government, and urban living seem to be persisting. Yet there are other indicators such as the emergence of a service economy, the quantum jump in high technology, and the intensification of globalization that suggest something new might, indeed, be emerging. The cultural changes such as the shift in styles, the change in values, and the linguistic turn could be the cutting edge of a larger transformation not yet completely clear to the contemporaries caught up in it. Various attempts at labeling this perplexing situation have not yielded any convincing consensus, since the suggestion of a second or “reflexive modernity,” advanced by Ulrich Beck and Anthony Giddens, has yet to catch on. A more ironic response to this conceptual uncertainty would be to call the last quarter of the twentieth century, provisionally, an era of “postmodern modernity.”49