POSTINDUSTRIAL TRANSITION

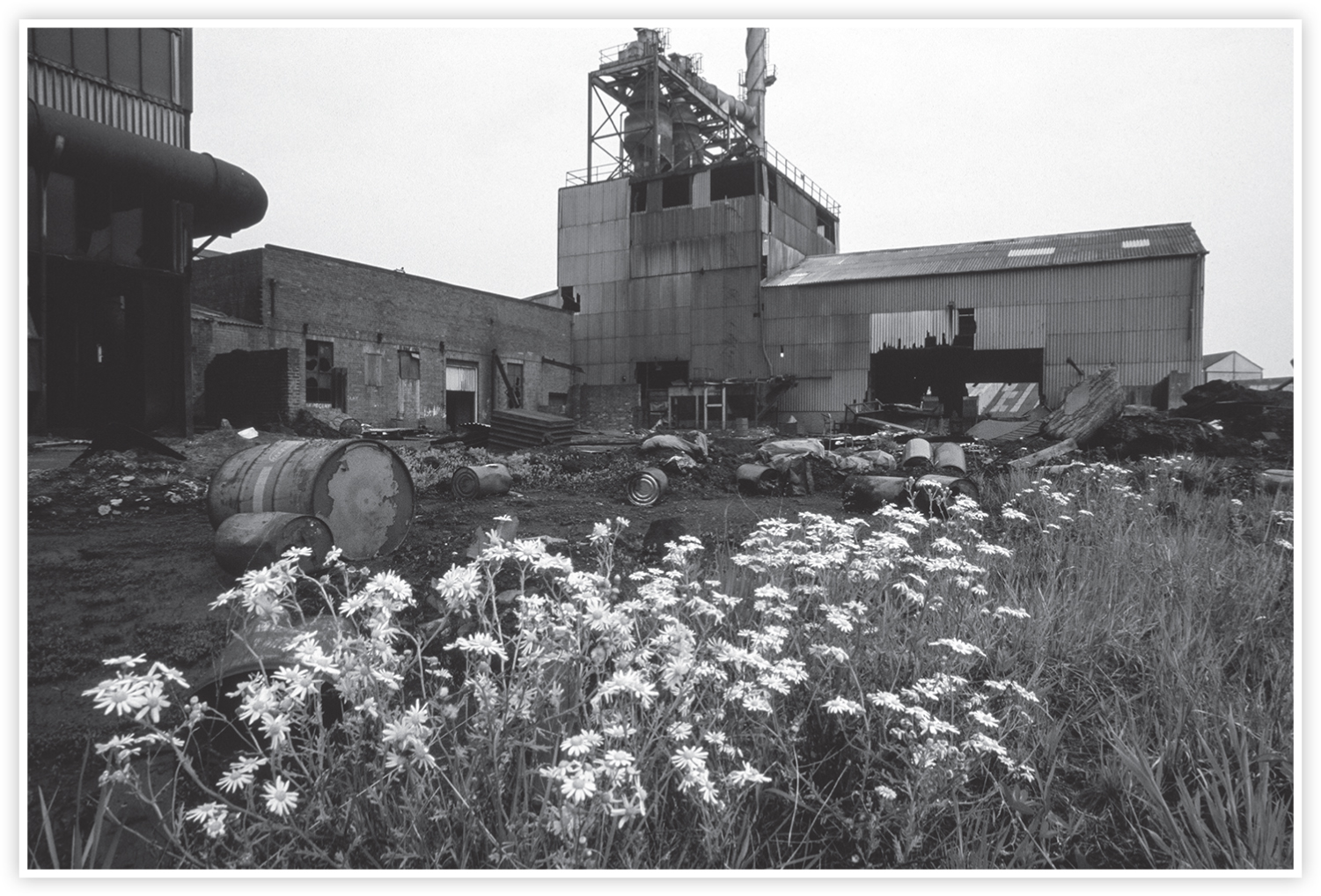

British deindustrialization, 1983. Source: Magnum Images.

On October 16, 1973, the six largest oil-producing countries on the Persian Gulf suddenly announced a 70 percent increase in the price of their crude. By using “oil as an Arab weapon” they sought to pressure the supporters of Israel in the Yom Kippur War into forcing Israel to withdraw from the Sinai Peninsula and the Golan Heights. Moreover, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), which controlled 40 percent of the global supply, also issued an embargo against the United States, Japan, and Western Europe “by monthly 5 percent cut-backs in the flow of oil.” Quadrupling from around three U.S. dollars to twelve dollars per barrel, the subsequent price increase stunned the industrial countries, since not only their heating and transportation systems but also a good part of their industrial production depended on Near Eastern oil. Recalling World War II shortages, the public panicked, lining up at filling stations, while governments frantically proposed rationing, lower speed limits, and prohibitions on Sunday driving to conserve gasoline. Even after a pro-Arab statement by the EC had restored supply, the Arab embargo shattered western confidence.1

This “oil price shock,” or Oil Shock, disrupted European economies and threw politics into confusion, since there was no quick way to substitute other energy sources. The Arabs were able to use oil to exert political pressure because the European Community depended on their crude for 80 percent of its supplies, since North Sea oil had not yet begun to flow. The price increase shifted the balance of power, for once, from the industrialized states to the raw-material countries, acting as a surtax that transferred profits to the Near East and allowed the producers to amass untold fortunes. By making everything that required petroleum more expensive, the steep rise in oil prices also triggered inflation because demand proved inelastic in the short run. Exaggerated by media alarmism, popular fears of lower living standards also contributed to a deep recession, which in effect ended the postwar boom that had lasted an entire generation.2 Misunderstood as a problem of the business cycle, the Oil Shock distracted attention from a more fundamental problem—the transition to a postindustrial economy.

Since leftist politicians failed to find effective solutions, the rise in oil prices, redoubled again in 1979, helped discredit Keynesian policies and encouraged a surprising revival of neoliberalism. Opposed to fascist and communist regulation, a small group of economists following Friedrich von Hayek had persistently advocated a reduction of government control of the economy. Going back to the liberal theoreticians of the eighteenth century like Adam Smith, these monetarists of what was called the Chicago school argued in favor of individual autonomy, free-market competition, deregulation, and privatization in order to restore entrepreneurial initiative. When countercyclical spending failed to stimulate robust growth and bring down the high inflation, such neoliberal prescriptions suddenly began to seem more attractive. One of their key converts was Margaret Thatcher, who weaned the Conservative Party from corporatism and then won the election of 1979, getting a chance to implement the neoliberal agenda as prime minister.3 The result of her tough policies speeded up and deepened the structural transition in Britain.

The turn to neoliberalism led to widespread attacks on the welfare state, seeking to cut back its excesses and to reverse direction toward self-reliance. Both objective pressures and subjective preferences combined in the call for lowering public expenditures. During the oil-induced recessions of 1974–75 and 1981–82 unemployment in the United Kingdom soared to over 10 percent, imposing huge costs on the exchequer. Moreover, the decline in tax receipts made it more difficult to keep funding extensive social programs. At the same time a growing number of middle-class voters, first in the United Kingdom but then also on the continent, revolted against the high marginal tax rates, approaching 90 percent in Scandinavia. Conservative parties profited from this resentment, demanding a reduction of welfare benefits, a decrease in unemployment payments, and a lowering of public assistance. While moderates wanted only to prune its proliferation, radical neoliberals intended to abolish the welfare state altogether. Psychologically understandable, this overreaction threatened to abolish social services just when they were most needed because of the restructuring.4

The dispute about how to respond to the Oil Shocks blocked the realization that the slowdown’s underlying cause was the transition to the postindustrial phase of modernity. The recession resulted not just from the business cycle but also from the shift of Fordist mass production to the Asian “tiger states.” Trying to stop the process of deindustrialization, which blighted entire areas and disrupted working-class lives, did soften its human impact but provided little hope for a resumption of growth. Gradually the failure of Keynesian countercyclical policies to overcome the stubborn combination of economic stagnation and high inflation shifted public sentiment toward neoliberal policies. The subsequent cutbacks of welfare-state expenditures helped make European industries somewhat more competitive. But it was ultimately the rise of the digital economy, fueled by computers and communication devices, that created new chances for the young and well educated.5 Together with the cultural revolt, this postindustrial transition ushered in a new phase of global modernity, creating both insecurity and opportunity.

OIL SHOCKS

Even before the Arab-Israeli war, the international economy showed signs of growing strains. The chief cause was the high cost of the U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War, which rendered President Johnson’s policy of having both “guns and butter” too costly in the long run. To relieve balance-of-payment problems, the Nixon administration in August 1971 decided to abandon the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates that had made international trade predictable. Once the weakening dollar was allowed to float freely, other currencies like the DM and the yen followed suit, gaining in value, which reduced the export advantages of Germany and Japan.6 Since oil revenues were denominated in U.S. dollars, the depreciation of the American currency eroded the profits of the producing countries, giving OPEC an economic motive to raise prices. The oil cartel was able to charge more, since the United States had just appeared to reach “peak oil” production, while the Europeans had no real source of crude of their own before the North Sea oil started to flow in the second half of the 1970s.

European countries were particularly vulnerable, as they had shifted their prime energy source from coal to oil during the 1960s. Most of the rebuilding after World War II and the Economic Miracle of the 1950s had still been fueled by anthracite coal, extracted from deep mine shafts in Wales, the Ruhr Basin, and Silesia. But oil won the energy competition not only because it was cheaper to produce and easier to transport but also because it offered additional advantages: For heating purposes, an automated oil burner could run continuously and cleanly, while a coal furnace required restoking and emitted noxious fumes. In transportation, petroleum drove the shift from public transport in coal-powered trains to individual mobility in automobiles since the latter was more flexible, allowing individual movement independent of fixed routes and timetables. And in industry, hydrogenation of coal was expensive, while petroleum derivatives opened up a whole new field of plastics for construction and consumer goods. Though coal-fired power plants persisted, the shift to oil was slowed only by the lack of European fields.7

The western governments responded to OPEC’s “oil blackmail” with a confused mixture of short-range actions and long-range rethinking. To calm public fears, they hit upon a series of measures that looked as if they were doing something but ultimately had little effect. In West Germany the social-liberal coalition instituted a driving ban for four consecutive Sundays, which created an eerie picture of not-quite-empty superhighways, since they were reappropriated by pleased pedestrians and bicyclists. Some countries like France drastically lowered speed limits in order to save fuel, but the problem was enforcement, since too often drivers simply ignored them. Other efforts such as rationing fuel created confrontations at the filling stations with owners not knowing how to deal with the reduced supplies and angry customers fighting over scarce gasoline. Journalist Sebastian Haffner therefore concluded: “We have to free ourselves from oil, even if the withdrawal is hard to cope with.”8 Only gradually did it become clear that, along with conservation, a more constructive reaction would be the development of alternate sources of energy.

As a result of OPEC’s reduction of oil production by about 7.5 percent, the West European economies fell into a recession that was both deep and long lasting. Though the precise figures differed in various countries, GNPs declined over 3 percent between November 1973 and the middle of 1975. In part, exaggerated fears were to blame, because they reduced consumer willingness to buy. In part, the recession was a result of government policies that reduced energy allotments to factories and private homes, for instance decreasing the workweek to three days in Britain in order to avoid blackouts. Finally, the recession was also induced by business decisions, such as anticipating dropping demand by reducing car production, which set a downward spiral in motion. As a result, unemployment inexorably rose to over 12 percent in the United Kingdom and Holland, aggravating the drop in purchasing power. Finally, the increase in energy costs also pushed up European inflation to 9.4 percent by 1983, which dampened business activity. The consequence of the downturn was the first major recession, which ended almost three decades of the postwar boom.9

Resuming economic growth was difficult because of the nasty “stagflation” that beset European economies after the rise in energy costs. This term was a combination of stagnation, indicating little growth, and inflation, suggesting a loss of buying power. Owing to the oil price increase, the expansion of the European economy did stall, accompanied by high unemployment and rising inflation. This unexpected predicament baffled Keynesian policy makers, since attempts to stimulate growth by government spending would drive up inflation, whereas efforts to stop currency depreciation would increase the number of unemployed. While Britain remained caught in a vicious cycle due to high wage demands and excessive government spending, West German chancellor Helmut Schmidt succeeded in decreasing inflation and joblessness by reducing some expenditures and applying limited stimulation.10 Ultimately only the strategy of “recycling petrodollars,” by getting the nouveau riche Arab elites to buy luxury goods and invest their gains, retransferred some of their earnings to Europe and revived some semblance of growth.

Unfortunately a second oil crisis from 1979 to 1981 nipped the weak recovery in the bud and triggered yet another recession. The overthrow of the shah of Iran by the Islamic revolution of Ayatollah Khomeini reduced the oil supply by 7 percent, and then the ensuing war between Iran and Iraq cut output by another 6 percent. This renewed drop in production pushed the price per barrel up to over forty dollars, once again doubling energy costs in real terms. The predictable result was another, even more severe recession. Unemployment grew to about 8 percent in France and Germany, private consumption stagnated, and inflation reached a new postwar high. Hence trade between advanced industrial countries declined by one-fifth, and industrial output shrank by over 10 percent. After three decades of growth, this second recession came as an even greater shock because it indicated that the difficulties were not just temporary in nature.11 Since the new crisis made incumbents look bad, Margaret Thatcher was elected in Britain in 1979, François Mitterrand assumed power in France in 1981, and Helmut Kohl became German chancellor in 1982.

The subsequent collapse of oil prices to twelve dollars a barrel by 1986 revealed that the anemic performance of the European economies actually had deeper causes. During the period of perpetual growth business had overinvested, generating idle capacity, while labor had become accustomed to high wages and long vacations. The subsequent curtailment of investment led to low productivity gains, miring European companies in mediocre performance. At the same time insistent union demands created a wage-price spiral that negated pay gains in real terms by pushing up commodity prices, perpetuating substantial rates of inflation. Many governments reacted with “defensive investments” to the growing worldwide competition, and the EC raised its external tariffs to protect native producers. The pressure of rationalization led to weak job creation, while rising expenditures for unemployment compensation limited funds for research and development. As a result external observers and internal critics increasingly talked about a “Eurosclerosis” that was rendering the Old Continent incapable of shaking off its lethargy.12

Though Eastern Europe appeared to have escaped the oil crisis, this impression turned out to be deceptive, since its consequences were ultimately even more deleterious. Shielded from world-market competition by the nonconvertibility of their currencies, communist leaders could gloat about the problems of “late capitalism” and predict its imminent demise. Members of the Comecon felt secure, since their oil was being supplied by the large fields of the Soviet Union and some smaller Marxist countries in the Third World. As a result of this protection, Soviet Bloc countries had even fewer incentives to modernize their smokestack, labor-intensive industries. With domestic growth practically stalled, however, they were forced to borrow from the West in order to supply those attractive consumer goods which they were unable to manufacture themselves. Eventually the Soviet Union raised its own oil price with a five-year moving average that slowed down the increase but kept costs high after prices once again declined on the world market. The postponed reckoning, when it finally came in 1989, turned out to be all the more severe.13

SCOURGE OF DEINDUSTRIALIZATION

Overshadowed by the oil crisis, the underlying process of deindustrialization proved even more challenging, since it destroyed the economic basis of high industrial society. Describing the closing of individual plants, the disappearance of whole branches of industry, and the general decline of manufacturing, this neologism was itself a product of the structural changes triggered by globalization in the 1970s. Its cause was the intensification of international competition, since developing countries in Asia were able to produce many consumer items more cheaply than mature economies, eventually putting their competitors out of business. The relocation of production was hastened by declining transport costs as well as technological innovations that automated production, reducing the advantage of a trained workforce. While consumers profited from lower prices, western producers lost their factories, creating structural unemployment and blighting old industrial regions. Unprepared for deindustrialization, the political elites misunderstood it as a problem of the business cycle and tended to defend the ailing industries rather than to invest in innovation.14

One key element was the decline of Fordist mass production of consumer goods such as textiles, which had already started in the 1950s. Once consumers had outfitted themselves with clothing after the war, overproduction intensified competition between firms. Many factories sought to survive through automation, borrowing in order to install new spinning and weaving machinery that needed fewer workers. Since this strategy did not return enough profit, energetic entrepreneurs tried outsourcing, shifting production to the European periphery in the South and East where wages were lower, while still designing clothes at home. When that did not work any longer, the bigger firms went to Asia, where wages were even lower. But these licensed manufacturers in Asia soon emancipated themselves and started to produce their own labels. As the making of items like T-shirts moved to the Far East, only a few firms such as Bennetton could hang on by combining European design with Asian manufacture.15 Quietly, one factory after another had to close, and its displaced workers, often women, struggled to find new jobs.

Another, more devastating factor was the coal and steel crisis that had been gradually eroding the industrial core of European countries since the late 1950s. The conversion from coal to oil as the dominant fuel and competition from open-pit mining in the United States and Australia made much of the continental coal too expensive, since it had to be extracted deep underground from narrow seams that rendered using machines difficult. Over union protests, one coal mine after another had to be closed during the 1960s and 1970s, putting hundreds of thousands of miners out of work. Even British and French nationalization and the concentration of German coal production in one Ruhr Basin company could not stave off the closures. The end of rebuilding war-ravaged cities and the conclusion of the Korean War also created a glut in steel, since one of the biggest consumers, the shipbuilding industry in Belfast and Hamburg, was also failing. Owing to its cheaper coal and lower labor cost, basic steelmaking shifted to Asia, with only specialty steel surviving. The EC sought to salvage production by dividing the market in a cartel-like fashion and encouraging the fusion of competitors like Krupp and Thyssen.16

Often overlooked, a third dimension of technological change pushed deindustrialization even into more advanced sectors of manufacturing. Initially the catch-up industrialization of the Asian tiger states had concentrated on taking over cheap mass production, but gradually higher-quality manufacturing developed as well in countries like Japan. Traditional European companies such as Zeiss in optics, Leica in cameras, AEG in appliances, and Grundig in electronics relied on their superior design, craft-trained workforce, and prestigious names in order to sell expensive items. But their Asian competitors were quicker in making use of innovations like computer chips and robotic production, first capturing the market for inexpensive mass products. Gradually engineering advances and stylistic redesign shifted the frontier of innovation to Asia, leaving many well-known European brands scrambling to compete. Soon the combination of technical sophistication and reasonable price made Sony, Canon, and Samsung household words in Europe, while one traditional name after another like the film producer Agfa disappeared.17

The chief consequence of these deindustrialization processes was the emergence of structural unemployment that proved resistant to political countermeasures. Simply put, only some of the jobs lost during the recession of 1973–75 returned with the recovery, creating a new plateau from which further jobs were lost in 1979–81, consistently increasing the jobless rate to over 7.5 percent. In Britain alone, about two million jobs vanished with deindustrialization during the 1970s, much more than were gained with the shift to financial services and high-tech employment. Skilled or semiskilled male workers over forty years of age were reluctant to move elsewhere and quite difficult to retrain for new careers. Miners, steelmakers, ship welders—workers such as these, once part of a labor aristocracy, were extremely bitter about losing not only their employment but also a major source of their pride and self-identity to a macroeconomic process they did not fully understand. In contrast, women and the young adapted more easily, albeit landing often in low-paying positions. The effect of prolonged joblessness was much political resentment and enormous cost increases for social services, called Sozialpläne, that tried to cushion the loss.18

The struggle over the closure of the Krupp steelworks in Rheinhausen, once the biggest in Europe, was a dramatic example of globalization logic and labor impotence. Situated on the Rhine River across from the Ruhr, the factory had been founded in 1897 because the local coal was used to transform iron ore shipped from abroad into high-grade steel. Though the works had just been renovated at great cost, manager Gerhard Cromme decided to close the plant because of the world-market glut of rolled steel. When he announced his decision on November 26, 1987, six thousand shocked steelworkers suddenly faced unemployment. The strong union waged a spirited resistance, occupying the bridge across the Rhine, mobilizing the prime minister of North Rhine-Westphalia, and appealing to public sympathy. Trying to preserve an entire way of life, the strikers intoned an emotional song: “Rheinhausen, you must not die.” Though the workers fought for 164 days, the factory was closed in 1993, the equipment partly sold to China, and the buildings torn down to make space for a trucking center, employing one-third of the previous workforce.19

The result of such profit-oriented decisions was the blighting of entire regions that had once been the industrial heartland of Western Europe. From the Midlands to Lorraine, from Lancashire to the Ruhr, abandoned factories stood with machines idled, windows broken, and grass growing through cracks in the parking lots. In working-class neighborhoods many apartments were empty and small stores boarded up. Men loitered in the street or congregated in pubs, while women scraped their meager cash together to buy a few victuals. The young were conspicuously absent, having moved away to more promising places. An air of depression and neglect hung over the afflicted communities, since hope had disappeared. Only in a few exceptional cases did new plants like Opel in Bochum pick up some of the slack, but even then they employed fewer workers than before. A few fortunate mines and steel plants were converted into industrial museums.20 But the examples of turning factories into condominiums or artists’ lofts were rare, since they required an affluent clientele. It was small comfort that the air became once again breathable and the water swimmable.

Shielded behind the Iron Curtain, Eastern Europe initially escaped the turmoil of deindustrialization, only to be overwhelmed by it after 1989. Even without its Stalinist distortions, Marxism-Leninism remained a high-industrial ideology based on factory production and the working class. Determined to prevent a repetition of the unemployment during the Great Depression, the communist leadership took pride in a policy of full employment that guaranteed everyone a job, even if much working time was spent on political indoctrination and on getting the shopping done. As a result of lack of investment, the basic industrial infrastructure crumbled, with much machinery decades old and in dire need of replacement. Moreover, the widespread desire for consumer goods drove communist governments into the trap of borrowing from the West, thereby becoming dependent on the class enemy.21 Western visitors no longer marveled but stared in wonderment: some of the most important industrial plants, from Nowa Huta to Eisenhüttenstadt, had already began to look like museums—while the workers were still using their machines!

NEOLIBERAL TURN

Unable to overcome stagflation and structural unemployment, the Keynesian consensus gradually eroded, making way for a resurgence of free-market approaches. Social democratic efforts at stimulating the economy through countercyclical government spending were only raising inflation, which was approaching 20 percent in Britain during the late 1970s. Moreover, labor-union demands for sharing the remaining jobs by cutting the workweek down to thirty hours would have made European goods even more expensive. Hence a growing group of managers and economists pleaded for more “courage for competition.” Arguing that government meddling in the economy, with the resulting high taxes and welfare costs, had priced European countries out of the market, these neoliberals called for drastic cutbacks in order to restore competitiveness and thus revive economic dynamism. In short, they proposed to fix the problem by not trying to fix it—that is, by letting the process of deindustrialization take its course. In the fierce policy controversy over whether to redistribute work or to let unrestrained competition revive the market, the latter position ultimately prevailed in the media and among the public.22

The controversial British prime minister Margaret Thatcher was the unlikely leader who spearheaded the neoliberal turn. Born in Lincolnshire in 1925 as daughter of a Methodist greengrocer, she studied chemistry at Oxford and later became a barrister. Joining the Conservative Party, she quickly rose through the ranks because of her outspokenness, moralism, and political shrewdness, becoming secretary of education in 1970 and succeeding the ill-starred Edward Heath as opposition leader after the Conservatives’ loss of the 1975 election. Influenced by neoliberal thinkers like Keith Joseph and the Institute of Economic Affairs, she gradually became a fervent free-market advocate, blaming Labour’s “culture of dependency” for the decline of Britain. Her international views were firmly anticommunist, leading her to denounce the Soviet Union. When James Callaghan’s Labour government failed to reduce inflation, unemployment, and strikes during the “winter of discontent” in 1979, she seized the chance to win the general election.23 As the first female prime minister, she set out to restore entrepreneurship so as to put Britain back on its feet.

The combative “Iron Lady,” as she was called, pursued monetarist policies aiming at nothing less than a fundamental transformation of British society. Upon assuming office, she cut government spending and lowered income taxes, shifting to indirect value-added taxation instead. To wean the country from socialism, she broke the back of the thirteen-million-strong trade unions by riding out the miner’s strike called in 1984 to prevent the closing of twenty mines. Getting the state out of the economy, she launched an ambitious privatization program, selling off utilities, nationalized industries like British Steel, and public housing (the council houses). The program was a mixed success, since monopolies in private hands remained inefficient and the later privatization of the railroads turned out to be a disaster. But by reviving the spirit of individual responsibility, she managed to push ownership of stock-market shares up from 7 percent to 25 percent and of homes up to two-thirds of the public. Her neoliberal restructuring polarized British society, accelerating regional deindustrialization but also sparking new prosperity by deregulating financial services.24

Initially François Mitterrand’s victory in the 1981 French presidential election bucked the neoliberal tide, as he was a committed socialist supported also by the Communist Party. He was born in 1916 in the Charente into a Catholic and nationalist family with his father being a vinegar producer. Studying law at the prestigious Ecole des Sciences Politiques, Mitterrand was active in right-wing causes, and after fleeing German captivity he became a minor official in the Vichy government until he joined the resistance in 1943. In the postwar period he served as minister in several cabinets and opposed the establishment of the Fifth Republic because a coup had put de Gaulle into power. As both a Socialist and a Machiavellian, he became a consensus challenger of the Left, attacking de Gaulle and his successors. During their twenty-three-year reign, the Gaullists had actually pursued centrist policies in the tradition of étatisme that were nationalist abroad and welfare-oriented at home, but they ultimately failed to end the second oil recession. Propelled by Giscard d’Estaing’s scandals as well as the economic woes, Mitterand managed to enter the Elysée Palace.25

The rapid failure of his socialist program, however, forced Mitterrand to join the neoliberal camp, albeit rather reluctantly. His initial reform program, a leftist Keynesianism had envisaged further nationalizations of industry, workers’ control over factories, and additional planning. Moreover, his government had also raised the minimum wage, lowered the retirement age, increased family allowances, and extended housing support, thereby pushing social transfer costs from 4.5 percent to 7.6 percent of GDP within one year. The creation of two hundred thousand new government jobs could not have come at a worse time, since it increased the budget deficit while neither inflation nor unemployment budged. In July 1983 a contrite Mitterrand had to admit the failure of his socialist experiment, because economic growth had refused to follow ideology. He was compelled to announce a harsh austerity plan that reduced government spending, froze wages, and decreased business taxes. Also, in order to stay in the European Monetary System, a humiliated France had to devalue the franc.26 The failure of Mitterrand’s Keynesianism reinforced the appeal of neoliberal Thatcherism, promoted in France by a neoconservative group of nouvelles philosophes.

The last of the new leaders, German chancellor Helmut Kohl, also sought to reenergize his country by turning away from unsuccessful social democratic policies. He similarly came to power as a result of the second oil crisis, which made the small, liberal Free Democratic Party (FDP) switch coalition partners to the CDU, overthrowing Helmut Schmidt. Born in 1930 in the Rhenish city of Ludwigshafen into a Catholic civil-service family, Kohl had lost his older brother at the end of the war. He studied political science and history at Heidelberg and joined the Christian Democratic Party as a teenager. Because of his openness to new approaches and his ability to network with people he rose within its regional ranks, becoming minister-president of Rhineland-Palatinate at the tender age of thirty-nine. Although his party won 48.6 percent of the popular vote in the 1976 election, the social-liberal coalition headed by Schmidt retained a bare majority. The disappointed Kohl remained opposition leader but became chancellor by winning a constructive vote of no confidence in October 1982, approved by a general election a few months later.27

Underestimated by intellectuals, Kohl firmly believed in the “social market economy” and therefore proclaimed a “spiritual-moral turnaround” of his own. As representative of business interests, the FDP, his coalition partner, had already called for “a policy to overcome the weakness of growth.” Ideologically opposed to the legacy of 1968, Kohl similarly demanded moving “away from the state, toward the market” by breaking up entrenched special interests and rehabilitating individual initiative. This change of course was supported by the Council of Economic Advisers, which also called for an improvement in competitiveness “by accepting the structural transformation.” In order to stimulate the economy, Kohl reduced public expenditures, rebalanced the budget, privatized assets like Deutsche Telekom, and deregulated business. Although the unions and the Social Democrats blocked more radical measures in the Bundesrat, this moderate neoliberalism reignited growth, raised incomes, and generated new jobs. Without abandoning social solidarity, the CDU/ FDP reforms managed to overcome stagnation and restore a sense of progress.28

As a result of these experiences, neoliberalism spread through Western and Central Europe, becoming the new policy consensus. The reputation of Thatcherism improved when, after several years of turmoil, the British economy finally started to revive, raising the value of the pound, resuming growth, and adding jobs by the early to mid-1980s.29 Moreover, in the United States the “Reagan revolution” conjured growth out of similar monetary policies, making Milton Friedman’s economics the new orthodoxy. Neoliberalism therefore proliferated from Italy to Scandinavia, allowing bourgeois parties that had been in opposition for decades to take power in unlikely countries like Sweden and Denmark. Moreover, with the help of regional EU funds, new Mediterranean members were also at last liberalizing their economies. Though the Soviet Bloc remained firmly opposed, even behind the Iron Curtain some daring economists in Budapest and Prague dreamt of market incentives, while restive Polish workers demanded increased benefits. Reinforced by globalization, the neoliberal wave swept all objections before it.

WELFARE-STATE CUTBACKS

The neoliberals’ favorite target was the proliferation of the welfare state, because its financial costs and extensive safety net seemed to stifle economic creativity. Critics such as businessmen, economists, and middle-class taxpayers used both economic and moral arguments to attack social policies, claiming that they made European products too expensive and created a mentality of dependency. But defenders of the welfare state in the trade unions, among client groups, and in the social sciences argued for the importance of solidarity in order to decrease tensions within society. The ensuing debate about the future of the welfare state therefore involved fundamentally different interpretations of capitalism and democracy, pitting individual initiative against collective security. During the postwar boom, economic growth allowed both views to be reconciled, but after the Oil Shocks their prescriptions started to diverge, triggering an intensive public discussion in which the anemic performance of the economy appeared to support neoliberal arguments.30

The chief impetus for cutting back the welfare state came from a widespread “tax revolt” against the high levels of taxation necessary for supporting its benefits. Inspired by the California Proposition 13 movement, European antitax activists emphasized that the top rate of income taxes of over 50 percent reduced incentives for high achievers. Inheritance taxes also tended to devour between one-third and one-half of the amounts bequeathed, making it difficult to pass a small firm on to the next generation. The high business taxes of around 50 percent on annual profits drove corporations to move their headquarters to so-called tax havens like Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, or the Channel Islands, where the rates were much lower. Finally, the antitax movement also had a moralistic undertone, claiming that the poor should simply work harder, and appealed to xenophobic resentment by refusing to pay for the support of penniless immigrants. Though its intensity varied regionally, tax resentment fueled the electoral success of rightist parties like the British Conservatives.31

Economists and columnists held the welfare state responsible for the growing loss of competitiveness of European businesses, due to its generous welfare provisions. They pointed out that in the EC people generally worked about one-third fewer hours per year than Americans since they enjoyed more holidays and longer vacations. Continental workers also tended to retire several years earlier than their U.S. counterparts, thereby adding to the cost of pensions. Each salary in Europe was burdened with a governmental component of about 50 percent, consisting of tax bites and social-security payments, compared to only about one-third for salaries in the United States. These burdens pushed the cost to businesses of the average hourly wage in Europe about one-quarter higher than in America—creating a sizable disadvantage for labor-intensive industries. As a result of considerably higher benefits, government social expenditures in 1980 averaged around 20 percent on the continent, compared with only 13 percent in the United States. Neoliberal commentators could claim with considerable justification that owing to such levies, the generosity of the European welfare state made its businesses less competitive.32

Defenders of the welfare state refused, however, to give up without a fight, claiming vigorously that “the Keynesian social democratic state has not failed.” Leftist politicians, trade union leaders, and social scientists formulated a series of counterarguments. They claimed that there existed a “moral responsibility” for strangers in need, requiring a civilized society to show its empathy. Moreover, they pointed out that during the crisis of deindustrialization support payments were more important than ever in order to keep the affected workers from utter destitution. At the same time, they emphasized the considerable achievements of social policies in expanding access to education, improving public health, making better housing available, increasing social security, and providing personal services.33 Moreover, left-wing economists stressed the importance of assuring sufficient demand for goods and services by income transfers to the poor. Finally, proponents of solidarity also claimed that a social safety net was essential for the functioning of democracy. Instead of being abolished, the welfare state should merely be reformed.

Judging by its rhetoric, Margaret Thatcher’s attempt to reverse the “dependence upon the state” was a radical approach, since she demanded a “new ethics of welfare policy.” One priority was to encourage self-help and charity, that is, voluntary solutions to social problems rather than government entitlements. Though she was loath to abandon the National Health Service altogether, she encouraged market elements such as the cooperation of physicians in groups and the introduction of private insurance. In contrast to prior Labour cabinets, she quickly stopped the futile effort of an incomes policy that tried to keep pay disparities from rising and, rather, encouraged monetary rewards for superior performance, which increased inequality. While not abandoning the network of various support payments, she changed the rhetoric, making it seem indecent to rely on the dole. Consequently the British system provided merely basic security rather than higher income replacement for the unemployed. Surprisingly enough, in spite of all of her attempts, tax rates and public expenditures declined only slowly, leaving the core of the welfare state untouched.34

The continental pattern, exemplified by the FRG, proceeded more cautiously in implementing cost containment to keep the Sozialstaat solvent. The German system was based on the principle of a male wage earner in a long-term industrial job, insuring him against misfortunes but leaving those without stable jobs to social assistance. The pension system, funded by “pay as you go” contributions of workers, and the generous medical coverage, consisting of a statutory health insurance, rendered change difficult. Already during the mid-1970s the social-liberal coalition started to make selective benefit cuts, limited pension increases, and demanded copayments while raising some contributions. During his chancellorship Kohl continued the focus on cost abatement via targeted reductions, fee increases, and a change in pension indexing, saving sufficient funds to permit modest increases in coverage. The French system was even more generous in supporting child care and family assistance. On the whole these modest adjustments kept the system functioning, although they failed to reduce its drag on competitiveness.35

The Scandinavian model’s invention of an “activating welfare state” provided a better solution, since upgrading skills rather than cushioning unemployment kept people in the workforce. From the 1970s on this high-taxation and big-benefit system had also come under increasing strain, forcing some cutbacks. But ultimately the pressures led to the constructive response of human investment so as to help workers to adjust to globalization. One secret of its success was the active-labor policy, which qualified the jobless for new tasks through retraining schemes and compelled their relocation, if need be. Another element was the flexibility of the employment market, with few protections but more support during periods of joblessness that made getting a new position easier. Finally there was also an exemplary gender dimension of care for children and the aged, allowing women to remain in the workplace instead of being hamstrung by family obligations. Keeping people working rather than supporting their idleness seemed not just more humane but also more costefficient, since it allowed taxes to be reduced.36

The reform efforts of the European welfare state therefore steered a middle course between radical Reaganomics and Soviet immobilism. In its rhetoric the Anglo-American program was an ambitious attempt to reduce the welfare state as much as possible in order to restore the dynamism of the free market. In contrast, the Soviet Bloc under Brezhnev counted on the collapse of capitalism and, given its limited foreign trade, saw little need to adjust to globalization pressures. The French and the Germans pruned the continental model of the welfare state just enough in order to keep it solvent, but their halfhearted efforts did not do enough to make it competitive again. The Scandinavian approach had greater success, because the new concept of an “enabling welfare state” invested in human resources and thereby kept both social protections extensive and living standards high. As a result of these moderate corrections, also undertaken in other continental countries like the Netherlands and Austria, the welfare state not only survived but shed much of its apathy and regained some of its competitiveness.37

HIGH-TECH OPPORTUNITIES

In contrast to leftists who lamented industrial decline, neoliberals welcomed the postindustrial transition as a series of exciting opportunities for growth and social change. They viewed the dissolution of the high industrial order not just as a loss of security but also as a chance to break the stranglehold of entrenched interests by creating space for innovation that would bring individual rewards and make society as a whole more dynamic. The very same technology that social democrats tended to castigate as a “job killer” appeared to conservatives as a stimulus for resuming growth, shaking up an all-too-complacent corporatism. Especially the younger generation was quick to respond to the introduction of information technology in the workplace and in private life, experimenting with new uses and developing software for novel applications. In order not to fall behind the United States and Japan, European governments increased investment in research and development, looking to fund national-prestige projects. Rejecting intellectual predictions of doom, neoliberals hailed high technology as a potential savior.38

This technology enthusiasm was a product of positive experiences with the introduction of new machines that revolutionized many aspects of daily life. For instance, the development of passenger jets shortened international travel during the 1960s, making transatlantic flights feasible for a mass public. Similarly the development of color television during the second half of the 1960s and the addition of video recorders, which could play rented movies, transformed entertainment habits. Also, the creation of pocket calculators in the early 1970s facilitated computation for accountants, replaced the slide rule for engineers, and made individual purchases easier when built into cash registers. Moreover, the gradual introduction of electronically enabled credit cards not only rendered checks superfluous but radically altered spending habits.39 The proliferation of such innovations changed personal lives and transformed economic relationships. The arrival of ever new gadgets like digital watches and the progressive decrease in their price endowed technological invention with a magic promise of facilitating a better life.

To stay at the cutting edge, European governments initiated a series of prestige projects, only some of which succeeded in the marketplace. The joint Franco-British development of a supersonic passenger plane, an engineering marvel named the Concorde that reduced flight times by half, did not prove commercially viable in the long run. Similarly the minitel, an ingenious combination of a TV screen, telephone, and computer, caught on only in France and was eventually displaced by the Internet. The German fast monorail train Transrapid also seemed promising, but only one line was eventually built, in Shanghai, since it proved too expensive. Other large-scale rapid-transit projects did become profitable, however, such as the French TGV and the even more extensive German ICE, which made flying for medium-range distances unnecessary by pushing rail speeds up to two hundred miles per hour. Another success was the Franco-German consortium called Airbus, which rivaled Boeing in producing efficient passenger airplanes.40 While not all planning bets were practical, some large projects did keep European expertise at the forefront.

The most revolutionary new technology was the computer, as both a supercalculator and an essential communication link. While research sponsored by the U.S. military got it started, the privatization of computer development through IBM was more important in producing innovative mainframes in the 1960s and 1970s. Western European states made efforts to support their own industries with Britain founding ICL, the French helping Bull, and the Germans underwriting Nixdorf and Siemens. But these “national champions” were unable to compete with the speed of American hardware and software development, since IBM cleverly shifted part of its research and manufacturing to the continent. Moreover, this large computational machinery was eventually outflanked by the invention of chip-based personal computers, coming first from Silicon Valley and then manufactured in Asia, exceptions like Nokia notwithstanding. Most software development also occurred in the United States, though in some areas such as business applications European firms like SAP could hold their own. However, the rapid adoption of computing in public and private use did bring Europe into the information age.41

Financial services became the new lead sector by profiting from information technology that made its transactions easier. Only computers could keep track of stock trading, exchange-rate fluctuations, and the like in real time, linking marketplaces around the world in split seconds. The deregulation of banking, authorized in Britain in 1986, encouraged trading by abolishing the distinction between retail and investment services, allowing traditional banks to speculate in a wide range of markets. Moreover, insurance companies and pension funds were also no longer content with the meager gains from traditional interest-bearing assets but began looking instead for larger returns in stocks, bonds, and currency transactions. Rising middle-class participation in these markets called for a new cadre of financial advisers to tell clients where to invest their money. Finally, the formerly forbidding banks began issuing credit cards and installing automatic teller machines for withdrawals, becoming a bit more consumer friendly. As a result, some financial centers like London and Frankfurt prospered, with hordes of young and well-paid investment bankers who acted like “masters of the universe” when speculating with other people’s money.42

Another service area propelled by technology was private broadcasting, introduced on the continent in response to political and commercial pressures. Since public monopolies like the BBC sought to educate as well as entertain, producing programming was rather expensive, requiring mandatory user fees. Considering public-radio and TV journalists to be more liberal than the “silent majority” of the population, conservative parties urged the establishment of competing commercial networks. Italy was the first to deregulate in 1976, which led to the establishment of twenty-five hundred local stations—and to the rise of the Berlusconi empire. Advertisers also pushed for privatization, since they stood to make much money in the electronic media. Reluctantly the major European countries allowed commercial competitors like SKY TV and SAT.1 access to the airwaves in the early 1980s, though setting firm regulatory limits. Aided by cable and satellite TV, an advertising-driven media industry emerged that catered to soft porn and violence while spreading conservative political messages.43 Ironically, the political project of the right undercut its own moral posturing.

Not all industries succumbed to global competition, since automobile production for instance reemerged stronger by adapting to innovation. The oil-price increase and Japanese competition pushed European manufacturers into a severe crisis by the mid-1970s, with some brands losing as much as one-quarter of their sales. Especially the mass producers of inexpensive cars like Opel, Fiat, and Renault were in trouble, since their small profit margins provided little cushion. These pressures revealed the inefficiency of British manufacturers like Vauxhall and Morris, and when Margaret Thatcher refused to bail them out with government money, they gradually went under or were bought up by the Japanese. On the continent, the French automakers were rescued through public funds, but German firms like VW, Mercedes, BMW, and Audi reinvented themselves through introducing industrial robots as well as adopting Japanese “just in time” methods. Moreover they also pushed into a higher market segment, making “German engineering” a code word for speed, luxury, and durability.44 In contrast Soviet Bloc car producers became even more outdated, largely collapsing after 1989.

The arrival of high technology in Europe therefore did create a series of new opportunities, but it was not the panacea that its proponents claimed. Airplane production, the writing of computer software, financial services, and the creation of media programs added new careers to the surviving jobs in older sectors like the automobile or machine-tool industries. Whole new regions like the Southwest of the United Kingdom, the South of France, the German Southwest, and northern Italy prospered. But the old industrial heartlands like the Midlands, the French Northeast, and the Ruhr were largely left out.45 In spite of their own efforts to develop a computer industry, most countries of Eastern Europe fell behind completely, because the Soviet Union directed its advanced research-and-development capacity toward weapons design and did not allow independent innovation in its satellites. While the risk takers in financial services could make enormous profits, many of the other service jobs, such as those in the call centers and big-box stores, were poorly paid. Rewarding the young and flexible, the emerging high-tech economy also introduced a new norm of high job insecurity.

POSTINDUSTRIAL SOCIETY

The disappointing performance of European economies after the Oil Shocks was not just a downturn of the business cycle but indicated a deeper transformation of modernity. While hardly realized by contemporaries, the 1970s revealed a fundamental “crisis of industrial society,” ending Fordist production in Western and Eastern Europe.46 Sparked by global competition, the process of deindustrialization pushed unemployment from virtually nothing during the three postwar decades to over 10 percent in 1985 and raised inflation rates to unprecedented levels. Only gradually becoming aware that this was a structural problem, social democrats like Helmut Schmidt tried to defend established industries, subsidizing their production in order to save domestic jobs. Demanded by labor unions, this strategy devoured much public money and only slowed rather than prevented the decline. In contrast, neoliberals like Margaret Thatcher let the market take its course, betting instead on the creation of new jobs through high technology and services. Sociologist Daniel Bell anticipated this development in the 1970s, predicting the emergence of a postindustrial society.47

Much of this transformation was driven by new information technologies that made old devices obsolete and stimulated fresh desires, creating novel products and services. Europeans continued to excel at incrementally perfecting existing consumer goods like washing machines and automobiles. But they lacked the Cold War complex of defense industries that sparked the development of computers, airplanes, and rockets in the United States and created civilian by- products. Moreover, their bureaucratic approach did not inspire individual inventiveness or provide start-up financing for chip-based miniaturization processes essential to hardware like personal computers, software like Microsoft, search engines like Google, and so on. European governments did increase their investments in research and development, producing their share of new patents that made it possible for them to participate in the digital revolution, which came largely from across the Atlantic.48 Therefore they were able to absorb the new technologies rapidly, combine them with traditional manufacturing, and thereby join the information age.

Along with the technological quantum leap, the intensification of globalization led to a relocation of much industrial production away from Europe. During the 1970s international trade, financial transactions, and cultural communication grew rapidly, thereby raising global economic exchanges to a new level. Because the so-called developing countries offered lower wage costs while shipping grew cheaper with containers, their competition with the highly industrialized regions in Europe increased, forcing firms to close their factories and outsource much of their production to Asia. When these licensed producers developed products of their own and improved their quality, Europeans could no longer compete, losing entire industries such as textiles, steelmaking, shipbuilding, and the like. In some areas continental companies succeeded in keeping design in their home offices so as to cater to continental tastes, and in other branches a shift from mass to luxury production kept them in business. But when coupled with high technology, this increasing globalization largely ended the era of Fordist production on the continent.49

The shift from Keynesianism to neoliberalism accelerated the transition to post-Fordism in Europe, since it allowed technological advances and global market forces to wreak “creative destruction.” The consensus on countercyclical policies frayed when public stimuli failed to break the stranglehold of stagflation in the wake of the Oil Shocks, thereby opening the door for monetarist advocates of the free market. Margaret Thatcher’s refusal to rescue moribund industries, her campaign for privatization, and her effort to balance budgets through cutting welfare expenses removed a long-standing barrier to market competition behind which unions tried to rally to defend their industrial jobs. Since it facilitated the transformation from a manufacturing to a service economy, this policy was successful in generating many new white-collar jobs in finance, the media, and cultural pursuits. But it came at a tremendous cost of regional deindustrialization and personal unemployment for redundant blue-collar labor. The alternative approach of an activating welfare state in Scandinavia was more successful in combining competitiveness with solidarity.50

As a result of leaving high industrialism behind, Europe entered a new phase of modernity in a transformation that had all the hallmarks of a third industrial revolution. If the first stage consisted of the pioneering development of textiles, coal, steel, and railroads from the 1750s on in Britain, the second stage from the 1890s on was characterized by science-induced growth in chemicals, electronics, automobiles, and airplanes, typical of Germany. That configuration gradually came to an end during the last quarter of the twentieth century because of another leap involving information technology, globalized competition, and neoliberal policies. Therefore the continent was no longer dominated by the shaft towers of coal mines, the glow of the steel furnaces, or the dry docks of shipbuilders but rather by the gleaming skyscrapers of banks, the soaring headquarters of media companies, and the daring designs of museums. In some sense they were still modern, having been built with the methods of high industry. But in another way their eclectic styles, patchwork jobs, and software-dependent products signaled a different kind of postindustrial modernity.51