RETURN TO DÉTENTE

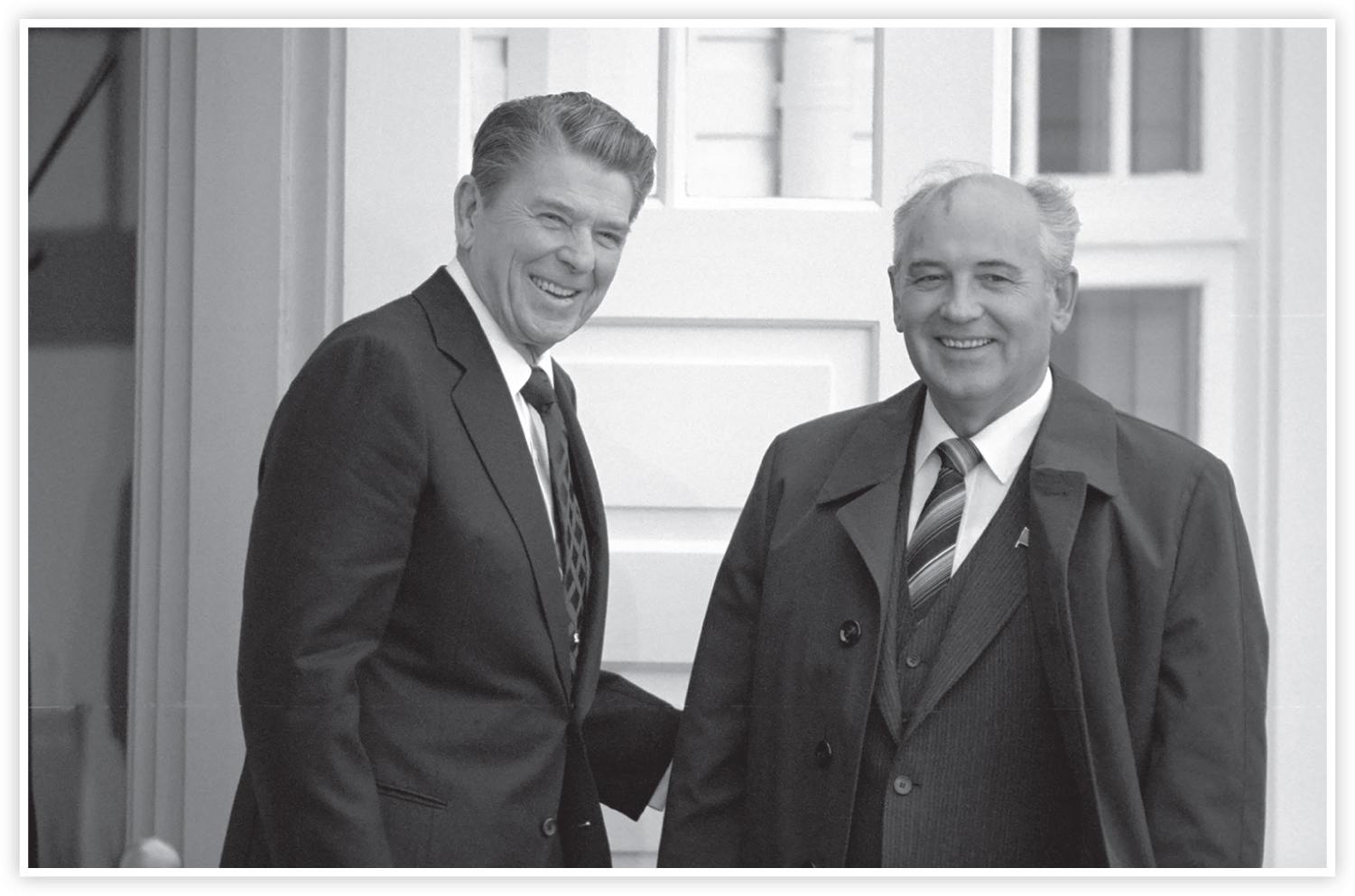

East-West détente, 1986: Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev. Source: Ronald Reagan Presidential Library.

On August 1, 1975, the leaders of thirty-three European states, the United States, and Canada assembled in the Finnish capital to conclude the Helsinki Final Act. After more than two years of negotiations, President Gerald Ford, General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev, and their colleagues signed “a document the size of a telephone directory” in a modest ceremony in front of whirring TV cameras. Their host, President Urho Kekkonen, expressed the hope that the agreement would be “the foundation of and guideline for our future relations and their further development,” finally ending the East-West confrontation. The core of the declaration consisted of ten principles such as the “inviolability of frontiers” and “nonintervention in internal affairs” and contained three general topics, or “baskets,” calling for political-military cooperation, economic-environmental collaboration, and respect for human rights. The Soviets were delighted with the guarantee of their wartime conquests, but western critics underestimated the power of the reaffirmation of human rights. By reducing fear, this Helsinki Declaration marked the high point of détente.1

Barely four years later a second Cold War had broken out, renewing the ideological, political, and military confrontation between the West and the Soviet Bloc. Tensions between the superpowers had gradually increased through proxy conflicts in the Middle East, Chile, Ethiopia, and Angola in which pro-communist and pro-western movements struggled for superiority. When the Soviet Union actually sent its own army to support a minority communist dictatorship in Afghanistan, President Jimmy Carter condemned the invasion and the United States began to supply the mujahedin uprising with arms through Pakistan. At the same time, the basing of medium-range SS-20 missiles in Russia prompted Chancellor Helmut Schmidt to propose a “dual track” approach of stationing U.S. Pershing missiles in the West while simultaneously negotiating for the general elimination of all intermediate-range missiles. The subsequent election of President Ronald Reagan increased the East-West antagonism, since he denounced the Soviet Union as an “evil empire” while Brezhnev retaliated by decrying American imperialism.2

The surprising end of the Cold War in 1989–90 has sparked a heated ideological debate over who deserves the chief credit. All through the superpower confrontation some statesmen and many spokesmen of civil society had tried to promote détente, but virtually no one foresaw the speed and extent of the East-West reconciliation. A triumphalist group of anticommunists argued that the West’s power-political realism, massive rearmament, and President Reagan’s “Star Wars” initiative to build a new antimissile system forced the Soviet Union to back down, because Moscow was falling behind technologically and its economy could no longer bear the cost of the arms buildup. In contrast, supporters of détente asserted that the subtle use of “soft power” undermined communism by awakening consumerist dreams, stressing human rights, and increasing political communication, all of which alienated the silent majority in the client states from communism, created a growing opposition movement, and even persuaded party leaders of the need to reform.3 Since both camps exaggerate their own contribution, the answer is likely to lie in the unwitting combination of armament and negotiation.

Focused on the bilateral superpower confrontation, the conventional views of the Cold War tend to neglect the constructive role of the Europeans during its final phase. Military planners in the East and West viewed the Old Continent primarily as a difficult battlefield that required a mixture of nuclear and conventional strategies so as to prevail in an armed conflict. Political leaders in Washington and Moscow considered their European partners recalcitrant auxiliaries, augmenting the power of their respective side but needing to be cajoled and kept in line. This bipolar perspective understated the agency of Europeans like de Gaulle and Brandt in the West and Tito and Ceauşescu in the East, who were no longer content to be ordered about and tried to steer a more independent course. Especially in the later stages of the Cold War, continental leaders like Helmut Schmidt and Erich Honecker developed a shared interest in maintaining détente, becoming increasingly insistent on reining in the bellicose superpowers. This European contribution to restraining and overcoming the second Cold War therefore needs to be more openly acknowledged.4

Paradoxically, it was the scientific advance of modernity that helped prevent the outbreak of a third world war by producing weapons that were too lethal to use. The development of hydrogen-bomb warheads and intercontinental ballistic missiles was a technological quantum leap that provided mankind with the power to annihilate itself. Thermonuclear war could no longer be fought, because it would involve the instant killing of millions of people, the additional death from radiation of untold numbers of civilians, and the devastation of the entire globe, rendering much of it uninhabitable for generations. Though they came close in the Berlin Wall conflict and the Cuban missile crisis, decision makers in Moscow and Washington pulled back from the brink when they realized that such a war was not winnable in a conventional sense, because the victor was as likely to be destroyed as the loser. This predicament pointed to the logical necessity to prevent such an inferno through diplomacy and disarmament.5 It was the realization of the unprecedented lethality of modern arms that compelled the ideologically hostile blocs to end their confrontation.

NUCLEAR DETERRENCE

The immense destructiveness of the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, fundamentally transformed the nature of warfare. Six years earlier Albert Einstein had alerted President Roosevelt to the potential of a “uranium bomb,” hoping to forestall its use by unscrupulous Nazi leaders. In August 1942 the Army Corps of Engineers began building research and production facilities in the desert near Los Alamos, New Mexico, for an endeavor called the Manhattan Project. The organizational competence of Brigadier General Leslie Groves and the scientific brilliance of Robert J. Oppenheimer overcame various obstacles, and produced three operational bombs. Rather than just demonstrating their use, President Harry Truman decided to drop two of them, euphemistically called “Little Boy” and “Fat Man,” on actual urban targets in order to force the Japanese to surrender. The unprecedented loss of life and physical destruction of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs achieved their purpose, ending the war in the Pacific. But the double strike crossed a moral threshold, both making the atomic bomb an ultimate weapon and inhibiting its use.6

Since nuclear bombs could, in theory, make their possessors invincible, both superpowers strove to perfect their technical capacities and build up a superior arsenal. When Truman hinted at the success of the first test during the Potsdam Conference, Stalin feigned to be unimpressed but ordered the immediate development of a Russian A-bomb as well. Shocked by the destructiveness of their brainchild, some nuclear physicists around Oppenheimer were beginning to have second thoughts, but efforts to curb the spread of nuclear weapons via the Baruch Plan failed because of the intransigence of both sides. Although the United States expanded its arsenal, the Soviets caught up surprisingly quickly with a crash program and the help of spies like Klaus Fuchs, detonating their own nuclear bomb in 1949. Intent on maintaining their superiority, by 1954 the Americans developed the H-bomb, which surpassed fission weapons by using thermonuclear fusion that released even more energy. Not to be outdone, the Russians produced one of their own a year later, initiating a technological stalemate that lasted for the subsequent decades.7

As a result of the superpower rivalry, a nuclear-arms race developed in which each side tried to overtake the other. Since the number of warheads remained a closely guarded secret, the intelligence services tended to exaggerate enemy capabilities in order to spur their politicians into authorizing greater production. As an experienced commander and strategist, President Dwight D. Eisenhower was basically skeptical of nuclear weapons, worrying about their irresponsible use, but the anticommunist fervor of advisers like Secretary of State John Foster Dulles and the McCarthyist witch hunt for domestic communists and “fellow travelers” forced him on occasion to talk tough. Unfortunately his initiative to create an International Atomic Energy Agency for the peaceful use of atomic energy under the UN umbrella did little to halt the proliferation of nuclear weapons. By 1960, the United States had accumulated about twenty thousand warheads compared to the Soviet Union’s sixteen hundred. But Nikita Khrushchev and his successors were bent on parity and eventually overtook the United States in 1978.8 Not content with watching anxiously, the British and French built up their own more limited nuclear deterrents.

The growing stockpiles of nuclear weapons created a pervasive climate of fear that came to be typical of the Cold War hysteria. The Americans suffered from a Pearl Harbor complex, dreading a surprise attack, the Soviets distrusted their capitalist adversaries, and the Europeans resented being caught in between. In order to maintain a second-strike capacity, Washington created a Strategic Air Command with dozens of nuclear-capable bombers like the B-52 constantly in the air, ready to attack the Soviet Union even after the United States might have suffered a first strike by the Red air force. Such nuclear readiness was accompanied by propaganda campaigns, teaching schoolchildren to “duck and cover,” that is, hide under their desks and put their arms over their heads. At the same time a vigorous civil defense campaign advocated the building of concrete bomb shelters in the backyard as well as the stockpiling of emergency rations, initiating a survivalist mind-set. Novels like On the Beach and movies such as Dr. Strangelove and Failsafe fed this atomic angst by dramatizing the lethal consequences of an accidental launch.9

The arms race accelerated further with the introduction of ballistic missiles capable of delivering H-bombs to any location within their range. Building initially on German V-2 blueprints but eventually far surpassing them, the formidable intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) were equipped with electronic guidance systems and matching warheads, and could span the distance between the two superpowers. The Soviet launch of the first earth-orbiting satellite in 1957, called Sputnik, shocked the western public because it demonstrated that Russia had a rocket capable of sending nuclear weapons not just to Europe but also across the Atlantic or Pacific, reaching the United States. Concerned Washington politicians invented a “missile gap,” pressuring President Eisenhower to authorize a major buildup. The Americans sped up their development of ICBMs so as to outdo the Soviets in space by landing on the moon but also, more importantly, to be able to deliver their warheads to the Soviet Union and thereby deter any aggression. Although Eisenhower refused to deploy nuclear weapons in Korea or Vietnam, Kennedy’s advisers made contingency plans to use them during the Berlin conflict and Cuban missile crisis, “the most dangerous moment in all of human history.”10

The Europeans feared the nuclear stalemate because it illustrated their dependence on the superpowers, whose ultimate decisions they could not control. The Soviet satellite states were welcome as auxiliaries for augmenting the reputed 175 tank divisions ready to roll through the Fulda Gap, but they had no input into Moscow’s nuclear decisions. The NATO allies Britain and France developed small nuclear deterrents of their own, but these were not big enough to ward off a Soviet attack, making them rely on the U.S. umbrella, while the FRG had forsworn nuclear weapons of its own. The smaller size of NATO’s land forces compelled the West to compensate for this inferiority with sea and air power such as nuclear submarines and ICBMs. Uncertainty over whether Washington would actually defend Western Europe with nuclear strikes, risking its own annihilation, led to the development of battlefield nuclear weapons, downsizing the warheads for infantry-support use, while technological advances produced multiple warheads (MIRVs) mounted on a single missile. Moreover West Germany, as the likely battlefield, insisted on a “forward defense.”11

Thinking about nuclear war was complicated because its unprecedented destructiveness rendered “the modern conception of war,” in Churchill’s words, “completely out of date.” Since a likely massive retaliation by the enemy made fighting such a conflict impossible, the purpose of armament had to be to deter its outbreak. Avoiding it, however, required an unmistakable signal that an antagonist was able and resolved to fight such a war—something about which political leaders could never be sure. In the 1960s the key phrase was “mutually assured destruction,” which would make a nuclear conflict unwinnable since the attacker would also be destroyed. But the uncertainty of transatlantic linkage led the Nuclear Planning Group of NATO to gradually embrace the doctrine of a “flexible response” that would resort to nuclear weapons only when losing a conventional war “as late as possible, and as early as necessary.”12 Entire think tanks tried to figure out ways to plan a first strike, but the risk of self-destruction due to uncertainty about the potential response fortunately kept the militaries from carrying out any such experiment.

The inherent irrationality of the nuclear-arms race finally inspired intermittent efforts at arms control, even if these fell short of real disarmament. The European peace movements periodically pushed for limitations, whereas Kennedy and Khrushchev realized how close they had come to nuclear Armageddon in the Cuban missile crisis. The Nuclear Test Ban Treaty of 1963 took a first step by prohibiting aboveground testing in order to reduce radioactive fallout. The Non-Proliferation Treaty of 1968, in which 183 nations pledged not to develop their own nuclear weapons, was more comprehensive, although India and Pakistan overtly failed to comply while Israel and North Korea did so secretly. Such confidence-building measures allowed the conclusion of a Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT I) and of an Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty (ABM) in 1972. These agreements froze the number of strategic weapons but not the number of warheads, which continued to multiply. By somewhat reining in the threat of technological self-destruction, these arms-limitation efforts, nonetheless, helped to further détente.13

REASSERTION OF EUROPE

Caught in the superpower confrontation, European leaders on both sides of the Iron Curtain grew increasingly restless about their lack of control over ultimate nuclear decisions. Since the recovery of prosperity had put postwar shortages behind them, memories of the suffering during and after World War II had gradually faded away. Moreover the ongoing process of decolonization was lifting the imperial burden and shifting the focus of foreign policy back to the continent. Finally, the progress of West European integration made it possible to speak with a more united voice, articulating European desires. Even if they were not ready to leave their respective Cold War camps altogether, continental leaders became impatient with just being informed about decisions made in Moscow or Washington and demanded a greater say in the affairs of their respective alliances. During the 1960s a rather diverse group of statesmen started to test the boundaries of the Cold War order, using the growing space provided by détente in order to assert their heterodox views.

French president Charles de Gaulle issued the first challenge to the bipolar system by calling for a “Europe from the Atlantic to the Urals,” independent of the United States. The successful general, liberator from Nazi domination, and postwar leader of France believed above all in the mission of his own country: “France cannot be France without greatness.” Assuming that other countries also pursued their own mystical destiny, he promoted a “Europe of the fatherlands” in which independent nations would cooperate voluntarily. Since he considered the bipolar division of the continent a historical aberration, he set out to restore the concert of Europe in which France would conduct the West and Russia the East, with Germany safely contained between them. Still resenting the lack of recognition of the Free French movement during the Second World War, he distrusted the British and wanted the Americans to get out of Europe. As a result, France officially left the NATO military structure in 1966, forcing it to relocate its headquarters to Brussels, and started building his own nuclear deterrent, the force de frappe.14

The Federal Republic of Germany presented the opposite problem of excessive compliance, since it still suffered from a “star pupil syndrome.” Although Chancellor Konrad Adenauer did not really understand the United States, he recognized that political cooperation and economic trade with Washington were essential for securing American defense protection. But with the Bundeswehr supplying most of the infantry for the Western Alliance, German defense planners wanted to increase their influence on NATO’s strategic planning. Some politicians like the mercurial Bavarian Franz Joseph Strauß even flirted with the idea of gaining access to nuclear weapons, but Bonn ultimately signed the nonproliferation treaty, trusting in the U.S. nuclear umbrella. Other conservatives had high hopes for Franco-German friendship after the conclusion of the Elysée Treaty in 1963, but German Gaullism remained a pipe dream, since the French deterrent was not strong enough to provide sufficient protection.15 Adenauer’s successors Erhard, Kiesinger, and Brandt firmly believed in the Western Alliance, though they claimed a larger voice within it.

In spite of rising criticism of the Vietnam War, the United States succeeded in reconciling its own leadership aspiration with the European desire for greater consultation in the alliance. As a result of their comradeship in World War II, the British firmly believed in a “special relationship” with Washington, based on common interests and similar outlooks. The smaller West European nations were also grateful for the U.S. nuclear umbrella even if some, like Sweden and Austria, remained formally neutral. But critical reporting of the U.S. counterinsurgency war in Southeast Asia increasingly alienated European intellectuals and fed a widespread protest movement among the younger generation, since not only news reports but also drastic pictures of brutality showed violations of proclaimed Western ideals. Recognizing the importance of the Old Continent and promoting a transition from bipolarity to polycentrism, the realist Henry Kissinger consulted European governments often enough to make them feel in the loop.16 Based on shared values and voluntary ties, the transatlantic relationship therefore proved sufficiently strong to withstand periodic strains.

Ironically enough, the Soviet Union had more problems with its allies, since it insisted on ideological uniformity and asserted its dominance more crudely. Titoism was a special irritant, denounced by Stalin as a dangerous deviation from orthodoxy because Yugoslavia tried to pursue its own road toward socialism. This “ism” was named after Josip Broz, nicknamed Tito, the charismatic partisan leader who managed to seize power in Belgrade at the end of World War II and bring the disparate provinces of Yugoslavia together into one country with the slogan of “brotherhood and unity.” Under his dictatorial rule, Yugoslavia allowed workers’ “self-management” of factories, permitted small-scale privately owned businesses, and encouraged western tourism, essential for gaining hard currency. Stalin and his successors considered Titoism a threat not because of its ideological innovations but because its independence threatened Russian control over the international communist movement. After being expelled from the Cominform in 1948, Tito became one of the key leaders of the “nonaligned nations movement,” which tried to escape the pull of bipolarity.17

Another maverick in the Eastern Bloc was Nicolae Ceauşescu, the brutal dictator of Romania who pursued an independent nationalist foreign policy. In power from 1965 on, he not only suppressed his pro-Russian competitors but also instituted a severe censorship over artists and intellectuals. As party leader and president Ceauşescu built an extensive cult of personality around himself and his wife, styling himself as a populist modernizer. The West came to admire his independence from Moscow, since he withdrew Romania from active participation in the Warsaw Pact and condemned the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968. After receiving more than $13 billion in western credits, he felt compelled to make a drastic effort to repay them, thereby lowering the Romanian standard of living to a struggle for bare survival in the 1980s. To gain support against Russia, he also sought closer ties with China and North Korea, and imitated their revolutionary radicalism. Nonetheless, the West courted him in the hope of creating differences within the Soviet Bloc, thereby vastly overestimating his importance.18

The growing Sino-Soviet rift shattered the ideological unity of the communist movement and transformed geopolitical alignments. During the Civil War in China the Soviet Communist Party liberally helped its Chinese comrades with weapons and advisers, although Mao was expanding Marxism-Leninism into a theory of “peasant revolution.” During the Korean War economic and military cooperation deepened further, with some sharing of military secrets. Though resenting Russian insensitivity to their own achievements, Chinese leaders still recognized Moscow’s leadership. But by the late 1950s a split developed, since the Soviets became interested in stabilizing relations with the West, while Mao grew more radical, initiating the disastrous policies of the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution. In the early 1960s this disagreement turned into an open break when the Chinese accused the Russians of being “revisionist traitors,” while the Soviets denounced Maoism as left-wing sectarianism. By the late sixties hostility between Moscow and Beijing had reached such a level as to trigger an undeclared border war along the Ussuri River.19

The initial attempts of European leaders to assert their independence during the 1960s therefore failed to break the bipolar structure of superpower confrontation during the Cold War. For all his rhetorical anti-Americanism, de Gaulle was careful not to sever relations with the Western Alliance completely, since he ultimately depended on the U.S. nuclear umbrella. Also the vociferous criticism of Vietnam as an imperialist war by the Left and the young did not change government policy, because continental elites were firmly committed to NATO and the EC. Similarly, the Soviet Union was ultimately more concerned with internal dissidents in Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Hungary than with the annoying antics of Tito or Ceauşescu. Only the breakdown of the Sino-Soviet alliance created a new geopolitical situation of multipolarity, which produced more diplomatic room for maneuver, an opportunity that was quickly recognized by President Richard Nixon.20 While the Europeans’ efforts to reassert a degree of independence remained unsuccessful, they showed that the polarized nations continued trying to regain control of their own destiny.

GERMAN OSTPOLITIK

The reversal of West German policy toward the East from revisionism to reconciliation was a major help in decreasing East-West tensions in Europe. Since the superpowers and direct neighbors shared an interest in keeping Germany divided, it was only logical that the initiative to end the continent’s division should come from Bonn. Abandoning the visceral anticommunism of the Hallstein Doctrine was not easy for the Federal Republic, since it meant that millions of ethnic refugees from Eastern Europe had to give up all hope of returning to their erstwhile homes by reclaiming the borders of 1937. Though the attempt to reduce hostilities by accepting the loss of Germany’s eastern provinces fit in with the general effort to create détente with the Soviet Bloc, Washington remained suspicious, because for the first time Bonn was pursuing an independent foreign policy.21 The strategy of working toward the long-term aim of ending German and European division by stabilizing continental borders in the short run gave Ostpolitik a paradoxical character that made it quite difficult to understand.

As foreign minister of the Grand Coalition, the charismatic Willy Brandt pushed for a change of approach toward Eastern Europe. Born as an illegitimate child in 1913, he grew up as a socialist in the Weimar Republic, fled to Scandinavia in order to fight as a journalist against Hitler, and returned in 1946 to the destroyed capital to help democratize the defeated country. More than a generation younger than Adenauer, he rejected the Catholic conservatism of the FRG founder who tried to make West Germany part of an occidental bulwark against the onslaught of the Bolshevik hordes. As mayor of democratic Berlin between 1957 and 1966, Brandt had ample day-to-day experience with communists, understanding both the possibilities and problems of dealing with the Soviets and East Germans. His defining moment was his disappointment in the lack of a vigorous American and West German response to the building of the Berlin Wall in 1961. The inability to prevent the closing of the last escape hatch through the Iron Curtain convinced him of the futility of anticommunist rhetoric and made him cast about for a more constructive solution.22

Elected chancellor in 1969, the Social Democratic leader initiated a new Eastern Europe policy that pursued several complementary aims: First, he would continue to take “small steps” like the border-crossing agreements with the eastern authorities, an arrangement intended to improve the daily lives of West Berlin citizens by allowing them to visit their eastern friends and relatives. Second, the shift from denouncing the very existence of the GDR (which was the Hallstein Doctrine) to dealing with its representatives pursued “change through rapprochement,” hoping to soften up eastern leaders by making them feel less threatened so that they would allow western media into their country and permit their citizens greater freedom. The ruling East German communists (SED) recognized the deviousness of this ostensibly harmless strategy by calling it an “aggression in slippers,” but their insistence on sharper demarcation (Abgrenzung) vis-à-vis the West failed to neutralize the attractiveness of consumer society. Third, the admission of responsibility for Nazi crimes and recognition of the loss of former territories as their logical consequence sought to reassure the eastern neighbors by repudiating refugee revanchism. Persuasively supported by Egon Bahr as Brandt’s adviser and emissary, this Ostpolitik struck a new chord by courageously accepting postwar realities.23

The process of reconciliation began with the signing of a nonaggression treaty with the Soviet Union on August 12, 1970. Since Moscow had blocked all earlier attempts to improve the Federal Republic’s relations with its satellites, Brandt entered into direct negotiations with the Soviet Union. Using Bahr as a back channel, the FRG distanced itself from revisionism by repudiating the use of force in order to normalize the situation in Europe. The most important concession was the promise of accepting the Oder-Neisse line as the eastern border of Germany by undertaking “to respect without restriction the territorial integrity of all states in Europe within their present frontiers.” Six months later, the Treaty of Warsaw repeated this declaration, although it maintained a reservation about final determination in a future peace treaty. In a surprising symbolic gesture of contrition, Willy Brandt then knelt at the memorial of the Warsaw ghetto uprising during his state visit on December 7, 1970, expressing German shame.24 Although the “letter on German unity” kept the door open to peaceful reunification, these reassurances removed the fear of German aggression in Eastern Europe that had tied nationalists to communism.

The next step was the four-power agreement on Berlin, signed on September 3, 1971, which eliminated the city’s status as a source of international crises. The text was a compromise between the western desire to secure the future of West Berlin and the eastern wish to have its sector serve as capital of the GDR. To prevent further disputes, the document essentially restated the existing rights and responsibilities of the World War II victors. Promising to refrain from another blockade, Russia assured that “transit traffic” would be “unimpeded” in the future. Moreover, “ties between the Western Sectors of Berlin and the Federal Republic of Germany” would be “maintained and developed,” allowing more integration into the West. Finally, travel between West Berlin and the surrounding GDR would be somewhat increased. The western quid pro quo was recognition of the de facto merger of East Berlin with the GDR, allowing East Germany to be governed from there. Ending the 1948 and 1958 confrontations over the German capital, this legal reaffirmation of the status quo guaranteed the continued existence of the western island in a communist sea.25

The most controversial aspect of Ostpolitik was the conclusion of the Basic Treaty, which recognized the GDR de facto while keeping the door open for future unification. After lengthy negotiations East and West Germany agreed on December 21, 1972, to “develop normal, good-neighborly relations with each other on the basis of equal rights.” Repeating the language of the nonaggression treaties, the document reaffirmed the inviolability of frontiers and the repudiation of the use of force. Eastern assurances of the regulation of “humanitarian questions” were accompanied by a western promise of closer “cooperation in the fields of economics, science and technology, transport … culture, sport and environmental protection.” Instead of full embassies, only permanent missions would be established in the respective capitals. In return for such quasi recognition, the FRG insisted in a separate letter that the treaty did not conflict with the aim of “a state of peace in Europe in which the German nation will regain its unity through free self-determination.” Over incensed CDU protests against making division permanent, the treaty barely passed the Bundestag by two votes, apparently bought by the East German secret police (Stasi).26

This relaxation of tensions culminated in the Helsinki Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE), which institutionalized détente despite unresolved ideological disagreements. Moscow wanted to have the postwar borders recognized and East-West trade intensified. The FRG was willing to make these concessions so as to preserve the chance for peaceful reunification with the GDR in the future. Washington and London were skeptical that anything good could come from such a parley but felt compelled to go along lest they be left behind. The smaller European countries favored the CSCE negotiations so as to enhance their security by concurrent arms-limitation talks in Vienna. The result of these multiple interests was a complex set of compromises that seemed to offer Brezhnev everything he wanted—an objection that Cold Warriors immediately raised in the West. But anticommunists underestimated the explosive power of the human rights stipulation, which provided a platform for dissident protest in the East.27 Hence the Helsinki Declaration helped turn acrimonious confrontation into cooperative competition.

The positive impact of Ostpolitik is easy to overlook, since it relied on soft power rather than on harsh rhetoric. Made in Europe’s name, some of Bonn’s painful concessions proved immediately beneficial: Apologies for Nazi crimes demonstrated the success of recivilizing Germans. Acceptance of the postwar borders reassured their neighbors’ new residents that they needed no longer fear a territorial revanchism. De facto recognition of communist control made it possible to reach a pragmatic modus vivendi that improved the lives of people caught behind the Iron Curtain. The long-term benefits of reconciliation with the East turned out to be even greater. The sincerity of German contrition robbed communism of the argument of Bonn’s revanchism. The increase of trade and communication made western consumer society appear more attractive. Finally, the insistence on individual human rights created space for an internal opposition to develop against the state socialist regimes.28 By demonstrating a peaceful western modernity, the shift from confrontation to détente speeded the erosion of the Soviet dictatorships.

SECOND COLD WAR

Unfortunately the euphoria of CSCE cooperation quickly evaporated in the heat of a renewed ideological confrontation stemming from multiple conflicts in the Third World. During the first stage of the Cold War, the United States and the Soviet Union had realized that fighting a hot war in Europe would be too dangerous for them, since Russia was contiguous to the potential battlefield and America remained committed to maintaining its nuclear umbrella. But in the postcolonial countries both states were “locked in conflict over the very concept of European modernity,” wanting to prove that either democratic capitalism or egalitarian communism was the correct path of modernization. Since the regimes of the developing states tended to be weak and in need of foreign aid, both sides tried to outflank each other in the Third World, using ideological appeals, material support, and military assistance.29 These local insurrections, counterinsurgencies, and proxy wars undermined détente between the superpowers and drew some Europeans back into the conflict as former colonial powers or as revolutionary advisers.

Though East-West relations had been deteriorating before, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan ultimately sealed the fate of détente. Jimmy Carter and Leonid Brezhnev were already sparring over African conflicts and human-rights issues. But the Russian decision to use its own troops to shore up a weak communist regime that had seized power in Kabul and was divided by personal intrigues turned growing tension into open hostility. In December 1979 the Soviet army quickly occupied the capital, other major cities and communication routes, and installed a puppet regime, but this action aroused a storm of international criticism and failed to gain sufficient support from the Afghan population. Instead, the Soviets were confronted by stubborn guerrilla resistance, which soon grew into a full-fledged Islamist uprising. Shocked by the direct Russian intervention, President Carter, pushed by his security adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski, decided on a massive covert operation to aid the mujahedin with weapons funneled through Pakistan. Though the superpowers did not fight directly, the unwinnable insurgency became the Soviets’ Vietnam.30

The NATO dual-track decision further heightened East-West tensions because it extended the arms race to intermediate-range missiles equipped with nuclear warheads. West European leaders worried that the increasing deployment of Russia’s mobile and accurate SS-20 rockets would create a communist advantage in a category not covered by the SALT agreement. German chancellor Helmut Schmidt was troubled by a break in “the continuum of deterrence,” since any level of Russian attack could be countered only by launching U.S. intercontinental missiles. While he preferred a “zero solution” of abolishing such missiles altogether, he proposed to modernize western intermediary forces. Concerned about “Soviet superiority in theater nuclear systems,” the NATO ministers decided in December 1979 to station 108 Pershing II missiles as well as 464 ground-launched cruise missiles in Europe. But recognizing Soviet worries, they offered at the same time to negotiate about the complete elimination of such weapon systems.31 When Moscow refused to talk, a war of nerves ensued in which each side accused the other of further escalation.

Rampant nuclear fear mobilized a huge peace movement in Europe that denounced the NATO decision as “a fateful mistake” and called for a return to “the original intention of détente.” Taking the Soviet stationing of SS-20s for granted, western activists tried instead to stop the NATO deployment of intermediate-range missiles, calling for an immediate beginning of serious arms-reduction negotiations. Growing spontaneously from below, the German branch of the movement was a colorful collection of intellectuals like Heinrich Böll, clergymen like Heinz Gollwitzer, Green politicians like Petra Kelly, leftist trade-union leaders, and various communist front organizations, paid by the East. Culminating between 1981 and 1983, the protests inspired a “women’s peace camp” at Greenham Common in Britain and mass demonstrations with between 300,000 and 500,000 participants in Amsterdam, Bonn, Brussels, and Rome. Though the United Kingdom and the Federal Republic nonetheless went ahead with the missile deployment, this huge mobilization for peace helped limit the second Cold War by dramatizing popular European anxieties.32

Instead of inspiring negotiations, the renewed confrontation once again pushed the world to the brink of nuclear war. In Washington the election of Ronald Reagan bestowed the office of U.S. president on a former movie actor who had scant knowledge of foreign affairs and was more interested in making anticommunist speeches than in working on policy details. Some of his chief aides such as Caspar Weinberger and Richard Perle were hard-liners who hated the very word détente as Kissinger’s legacy. In Moscow the aging alcoholic Leonid Brezhnev was increasingly incapacitated, followed in short order by the equally ailing Yuri Andropov and Konstantin Chernenko, making Russia unwilling to compromise. The Soviets’ unprovoked downing of Korean Air flight 007 provoked outrage in Washington, while Moscow misread the provocative NATO maneuver “Able Archer” as preparation for a nuclear first strike and put its forces on highest alert.33 But when Soviet radar erroneously reported an American missile attack, Lieutenant Colonel Stanislav Petrov fortunately refused to launch a counterstrike, saving the globe from incineration.

Owing to the failure of limitation efforts, the arms race intensified further with a new generation of weapons systems such as the ill-considered “Star Wars” initiative. As the Soviets kept adding warheads and developing new missiles, the hard-liners in the Reagan administration, only somewhat restrained by Secretary of State George Shultz, insisted on a massive rearmament program, including the MX missiles and the B-1 bomber. But the problem with the MX was that its silos could be attacked unless they were defended from incoming rockets. When Reagan heard the phrase that it might be better “to protect our people, not just avenge them” during a briefing, he seized upon building an antimissile defense system that would destroy incoming warheads with laser beams from space satellites (hence the initiative’s graphic nickname, “Star Wars”). West European leaders were appalled by the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), since the prospect of an antimissile system rejected decades of deterrence theory by reviving a first-strike possibility and also decoupled American security from their own. Feeling threatened and angry, the East European leader, General Secretary Andropov, warned: “Washington’s actions are putting the entire world in jeopardy.”34

Intent on preserving the achievements of détente, European leaders grew increasingly frustrated with American bellicosity. Members of the peace movement tended to blame U.S. recalcitrance for lack of substantial progress in the Strategic Arms Reduction Talks (START). French president François Mitterrand, especially, considered Reagan’s anticommunist rhetoric counterproductive, since he needed the domestic support of his own Eurocommunist party. Doubting the project’s technical feasibility, British prime minister Margaret Thatcher also intensely disliked the costs of SDI and sought to rein in its excessive expectations. And finally German chancellors from Willy Brandt to Helmut Kohl believed in “a community of responsibility” that included their eastern cousins, as they were seeking to maintain a dialogue with East European leaders like Erich Honecker. Having to live in close proximity to their communist neighbors, continental statesmen rediscovered a sense of common fate across the Iron Curtain that made them intent on moderating the rising hostility between the superpowers.35

During the second Cold War the Europeans therefore played a restraining role in the strategic triangle between their own continent and the two superpowers. Since the Helsinki Declaration had lessened most continental conflicts, the renewal of confrontation clearly resulted from the rivalry between the United States and the USSR in the Third World and in the arms race. After the Europeans’ withdrawal from empire had freed them from such responsibilities, the former imperialists were no longer directly involved in the ideological conflicts of the postcolonial countries. But fearing that they would have to bear the brunt of a third world war, European governments and the public were highly interested in the progress of arms-control negotiations. While the ultimate decisions were made in Moscow and Washington, continental leaders exerted considerable pressure on the superpowers, making the case for the benefits of peaceful modernity. Though the precise impact of their entreaties is hard to measure, European moderation did contribute to keeping the second Cold War from spinning out of control.36

RETURN TO DÉTENTE

Ultimately the failure of efforts to win the East-West confrontation prompted a return to détente in the second half of the 1980s, ending the Cold War once and for all. Slowly Moscow and Washington became disenchanted with the Third World strategy of trying to change the power balance by installing friendly regimes in developing countries, because that effort turned out to be costly and unreliable when clients like Egypt switched sides. Moreover, the futility of the arms race gradually dawned on American and Soviet leaders, since the implicit goal of nuclear superiority was receding while the number of their own nationals likely to be killed in a nuclear exchange steadily increased to encompass most of their population. At the same time the impressive size of the peace movement on the continent showed the public’s mounting revulsion against the East-West conflict, encouraging the European leaders to exert restraining pressure on the superpowers. Nonetheless it took almost half a decade to overcome the ingrained hostility and suspicion between two ideological blocs.37

Instead of Reagan’s belligerence, it was actually his relative moderation that laid the basis for peaceful accommodation with the Soviet Union. While hawks dominated the public rhetoric during his first term, the U.S. president deeply abhorred nuclear weapons and sought to escape from the trap of mutually assured destruction. Arms-control advisers like Paul Nitze and George Shultz gradually gained influence with the argument that once there were enough warheads and missiles to blow up the globe, further stockpiling became pointless. On January 16, 1984, Reagan proclaimed programmatically: “We want more than deterrence; we seek genuine cooperation; we seek progress for peace.” This was a clarion call to move from hostility to realistic reengagement with Moscow—to reinvigorate arms-reduction talks, change the tone of the relationship with the Kremlin, and resolve the remaining regional conflicts in the Third World. Though the media paid insufficient attention to this message, since it contrasted with his previous hard-line image, this conciliatory agenda dominated Reagan’s second term.38

At the same time Mikhail Gorbachev’s assumption of leadership brought to power in the Kremlin a younger generation that was willing to engage in “new political thinking” at home and abroad. While the ailing Brezhnev, Andropov, and Chernenko had been averse to change, their successor understood the need to overcome the widespread stagnation. The new general secretary was an orthodox Leninist who wanted to rescue socialism by resuming Khrushchev’s legacy of innovation so that it could reach its full potential. Domestically that meant shaking the party functionaries and state bureaucracy out of their lethargy and abolishing corruption. In particular the economy, strained by the arms race, needed reenergizing through more competition, through opening up to international trade, and through importing new technology—not to produce more weapons, but to fulfill popular dreams of consumption. The key concepts of this program were the “restructuring” (perestroika) of socioeconomic relations to make them more flexible as well as “openness” (glasnost’) in public discussions so as to correct mistakes.39 This sweeping agenda brought a fresh spirit to Russia.

Part of this program involved a changed attitude toward international politics, with a view toward ending Soviet isolation by abandoning traditional Stalinist precepts such as the “two camps” theory. Improved relations with the West would facilitate economic recovery as well, which Gorbachev knew was sorely needed. But the hawks in the Reagan administration made reconciliation difficult, since they did not trust the new Russian leader and continued with their provocative rhetoric. As a result the Soviets refused to withdraw from Afghanistan, even increasing their military efforts in 1985 and 1986. But remembering the suffering of the Second World War, Gorbachev hated nuclear weapons, since he worried that the globe would be utterly devastated by fighting a nuclear war. Hence Russia announced a unilateral moratorium on weapons testing and even went so far as to propose general disarmament, abolishing all nuclear weapons, although this suggestion was not taken seriously in Washington. At the 1985 Geneva summit, Reagan and Gorbachev could only concur that “a nuclear war could not be won and must never be fought,” but they disagreed on everything else.40

Disappointed in the lack of progress, West European leaders pushed for a return to détente while East European dissidents tried to reunite Europe from below. Getting on well with Gorbachev in spite of her pronounced anticommunism, Prime Minister Thatcher encouraged his agenda for domestic reform and his arms-control efforts. President Mitterrand tried to mediate between Moscow and Washington, pointing out that Reagan was less bellicose than some members of his entourage. Moreover, West German chancellor Kohl succeeded in hosting the East German SED secretary Honecker for a state visit in order to strengthen ties between the two Germanys, while Willy Brandt and SPD leaders made unofficial contacts with other East European politicians. Finally, intellectuals in Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and Poland began to revive the concept of Mitteleuropa, claiming that their countries at the heart of the continent were more Central than Eastern European, politically and culturally, since they wanted to escape Soviet domination through civil-society contacts.41 Reinforcing one another, these efforts improved the East-West climate.

Although it was a diplomatic failure, the 1986 Reykjavik summit initiated the thaw in Cold War mind-sets that made subsequent agreements possible. Deeply disturbed by the horrible consequences of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant disaster, Gorbachev made a series of radical unilateral proposals such as scrapping the Soviet Union’s controversial SS-20 missiles. Meanwhile, Reagan had gotten the impression that he could persuade the Soviet leader to abolish nuclear weapons altogether while maintaining SDI development. In fifteen hours of negotiations in the Icelandic capital, both leaders competed with each other, with Reagan offering to eliminate intercontinental missiles and Gorbachev to abolish all nuclear warheads. “All nuclear weapons? Well Mikhail, that’s exactly what I’ve been talking about all along,” the U.S. president queried. “Then why don’t we agree on it?” the Soviet leader replied. This stunning agreement came quickly undone, however, when Reagan insisted on his pet project of developing Star Wars. According to Shultz, “Reykjavik was too bold for the world,” but it did start the crucial shift toward the second détente.42

The improvement of the international atmosphere led to the conclusion of several crucial arms-limitation agreements. Increasing trust between Washington and Moscow scuttled hard-line efforts to reinterpret the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty in a way that would allow SDI development. More importantly, negotiators at Geneva succeeded in signing an Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty following the “zero option” of eliminating all nuclear-armed missiles with a range between three hundred and three thousand miles. Although these ballistic weapons amounted only to about 4 percent of the nuclear arsenals, this agreement was nonetheless “a great success,” since it reassured the Europeans on whom such missiles were targeted. More importantly, such progress also revived the Strategic Arms Reduction Talks, which included the entire missile and warhead defense systems. In a preliminary agreement, both sides consented to deep cuts of 50 percent of their arsenals, limiting warheads to six thousand and delivery systems to sixteen hundred, including land-, sea-, and air-based missiles. Since new issues such as submarine-launched cruise missiles complicated the talks, they were concluded only in 1991.43

The credit for ending the second Cold War must therefore go to a combination of unlikely leaders and policies. Even if the U.S. buildup was responsible for raising the costs of the arms race, Reagan’s change of tone from belligerence to cooperation was essential for lessening superpower tension. While they had no power over ultimate decisions, European leaders from Thatcher to Kohl kept lobbying for an accommodation with the Soviet Union, calling for arms reduction. But ultimately it was the arrival of the post-Brezhnev generation of Russian leaders represented by Gorbachev that was crucial in sending positive signals such as the long-sought withdrawal from Afghanistan. Though Gorbachev’s reference to a “common European home” in several speeches was designed to soften NATO, it suggested a shared interest in disarmament on both sides of the Iron Curtain. Made possible by the improving East-West climate, the gradual abandonment of the Brezhnev doctrine also created space for satellite regimes to experiment with reforms, encouraging dissidents to speak up.44 As a result the second détente not only limited but actually ended the Cold War.

NUCLEAR PEACE

By threatening the very survival of humanity, the development of nuclear bombs and intercontinental missiles compounded the negative dynamic of modernity. The construction of fission and fusion bombs made it possible to unleash unprecedented amounts of destructive energy from which neither combatants nor civilians could really be protected. At the same time the design of intercontinental ballistic missiles offered a delivery system reaching all corners of the globe, leaving no place to hide. Moreover, this arms race between the superpowers was a self-propelling process, since engineers sought to outdo each other with clever innovations while the military strategists wanted to create a bigger stockpile so as to gain first-strike capability or at least assure second-strike retaliation. Horrified by this growing arsenal, members of the scientific community argued that the use of these weapons would inevitably create a “nuclear winter,” rendering the earth uninhabitable for generations to come.45 Thereby the optimistic technological utopias of the 1950s turned into the frightening dystopias of the 1970s.

Fortunately, the common interest in survival across the Iron Curtain strengthened the incentive for cooperation at the same time, reinforcing the benign potential of modernity. Communist peace propaganda appealed only to leftist minorities in the West because it clashed with the militarization of eastern society. More constructive was the western emphasis on human rights, which provided some cover for eastern dissidents in dealing with political repression. But the main voice for peace was the grassroots movement against nuclear weapons, which campaigned for disarmament so as to keep the superpowers from destroying humanity. Led by intellectuals like Alva Myrdal, the campaign spilled over into the eastern satellite states. The increase in civil-society connections through academic exchanges, trade contacts, city partnerships, and athletic competitions, which allowed people to meet and exchange ideas, created a growing sense of commonality in facing the same predicament and inspired them to argue in favor of lessening hostilities. Though its impact is difficult to measure, this dialogue also contributed to restraint.46

During the second part of the Cold War after 1961, repeated cycles of conciliation and confrontation rendered it unclear which face of modernity would ultimately prevail. Though the Cuban missile crisis shocked the leaders in both Moscow and Washington by showing how close they had come to destroying the globe, the arms race continued, since neither side was content with nuclear parity. In Europe the nuclear stalemate created a strange stability by enforcing strict spheres of influence that kept the West from supporting the Prague Spring or the Polish Solidarity movement while restraining the East from intervening during the Portuguese Revolution. After the Helsinki agreement, the confrontation shifted to the decolonizing countries in a series of revolutions and counterinsurgencies that led to bloody proxy wars in Asia, Africa, and Latin America and contributed to the unraveling of détente. But once again both sides were disappointed because these local struggles in places like Nicaragua or Afghanistan proved costly and uncontrollable. Only after it became evident that neither outbuilding nor outflanking worked, was it possible to end the second Cold War.47

Ultimately both dimensions of modernity contributed to the peaceful outcome to the East-West conflict by offering a combination of fear and hope. On the negative side, the unwinnability of a nuclear war finally convinced leaders in Moscow and Washington that their shared interest in survival outweighed the potential gains from a first strike, since an aggressor might not be able to enjoy the fruits of victory. At the same time, the inconclusive results of local conflicts in the Third World, which resisted being pressed into a Cold War schema, made it clear that neither superpower would succeed in shifting the global balance of power permanently to its advantage. On the positive side, the increasing dialogue across the Iron Curtain after Helsinki provided a check on the rising tension, since it let politicians and citizens discover that the common interest in survival outweighed hostile propaganda stereotypes. Regardless of ideological affiliation, European leaders finally understood that they needed to work together in order to revive détente lest their countries become the battlefield of World War III.48

In his testimony before the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee in April 1989, the old Russian hand George Kennan announced that the Cold War had finally ended. Worried by the weapons buildup, he pointed out that the nuclear arsenals were vastly redundant: “Owing to their overdestructiveness and their suicidal implications, these weapons are essentially useless from the standpoint of actual commitment to military combat.” Commenting on the momentous changes initiated by Gorbachev, he added that the Soviet Union was no longer a military opponent: “That country should now be regarded essentially as another great power” with its own history and aspirations, which “are not so seriously in conflict with ours as to justify the assumption that the outstanding differences could not be adjusted by the normal means of compromise and accommodation.” To end the dangers of accident and proliferation, a substantial arms reduction agreement should be signed as soon as possible.49 This sage advice represented one of the voices of reason that helped conclude the conflict and open the door to a more peaceful future.