The Joys and Sorrows

of the Desert Survey

When many people think of archaeologists they picture them on excavations scratching away in the dirt, removing the soil in minute increments with trowels, small brushes, and dustpans, and in extreme cases, using dental tools to clean objects embedded in the ground. While this image is partially true, there is another important dimension in which the archaeologist plays a critical role in understanding our human past, one that involves little or no excavation whatsoever.

After all, how do archaeologists find ancient sites and how do they know where on those sites they should excavate, should they decide to do so? What about sites that, for whatever reason, will never be excavated, but nevertheless, should be as accurately recorded as possible? How should they be documented for posterity? Most archaeologists are acutely aware of the great value that surveying plays in our overall study of the material remains of the ancient past. Surveying is a relatively quick and highly cost-effective method of obtaining a vast amount of information. This is a very attractive prospect to most archaeologists who are almost always desperately short of funds to conduct their fieldwork. Our teams over the years have divided survey efforts in the Eastern Desert into two major types. We call them ‘site extensive’ and ‘site intensive’ surveys. They are not mutually exclusive and overlap each other to some extent in the results they achieve.

A site extensive survey, at least the way we conduct one in the Eastern Desert, involves a small team usually comprising no more than two of us, ideally accompanied by a very capable Bedouin guide, searching for ancient remains. The guide also acts as the cook, sometimes driver, and, hopefully when needed, vehicle mechanic. Many of these guides have become close friends over the years and are fonts of wisdom not only about the locations of ancient sites, but about desert flora, fauna, and Bedouin lore. The ancient sites we seek might be roads, unfortified road stations, or other remains such as praesidia, villages, quarrying and mining communities, cemeteries, and ports. Usually this type of surveying involves investigating a fairly wide geographical area with immediate objectives that include checking Bedouin reports about the existence of ancient sites and, if found, noting their existence by plotting them on a map using global positioning system (GPS) technology.

In addition to plotting the site's location using GPS, during a ‘site extensive’ survey we also estimate the approximate number of buildings and size of a site, its age (usually from potshards we collect, but occasionally, when lucky, from inscriptions and coins), and its function; the latter is not always possible. We usually take many photographs and also make quick sketches of architectural remains. This method of site extensive surveying has the advantage of being relatively inexpensive to conduct and allows us to develop an archaeological and historical picture of a number of sites spread across a relatively broad expanse of terrain in a rather short amount of time.

Global Positioning System Technology

GPS is an ingenious invention that became available and affordable to the general public worldwide in the late 1980s. Basically this is how it functions: the United States Department of Defense launched twenty-four satellites into orbit around the earth. ‘Spare’ satellites are occasionally launched to replace older ones, which sometimes results in more than two dozen in earth orbit at one time. Orbiting at about 20,200 kilometers in space, these satellites continuously emit specially coded signals, twenty-four hours a day, year in and year out. At least four satellites are visible above the horizon at any point on the earth's surface at anyone time. Triangulating three or more of the satellites using a rather inexpensive hand-held receiver allows the operator to determine, with a fair degree of precision, his point on the surface of the earth. The more satellites’ signals one can obtain with the GPS receiver, the more accurate the reading, up to within a few meters or better. The reading is then digitally displayed on the screen of the receiver in the form of latitude and longitude. This method of site location is quick and usually very accurate and dispenses with the old fashioned compass bearings that may be extremely inaccurate. Also, if there are no obvious geographical landmarks, such as distinctive mountain peaks, in the area from which to take compass bearings, it is impossible to obtain accurate coordinates for site location; such a situation makes GPS even more attractive. The Russians have a similar system, called Glosnass, as do the Europeans; theirs is called Galilee and is currently being integrated with the GPS. In theory, GPS can also provide measurements of elevations above sea level, but we have never found the results very reliable.

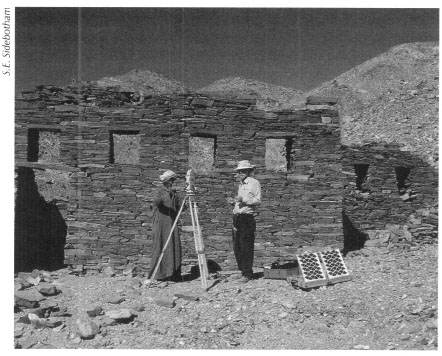

Site intensive survey work involves more labor than the site extensive variety. A site intensive survey usually comprises a slightly larger team than a site extensive one. These team members remain at one site for a relatively extended period, depending upon the size and complexity of the archaeological remains. During this type of survey we draw detailed measured plans and, often, architects’ elevation drawings of the more important or better preserved buildings. We undertake site intensive surveying when we deem the ancient remains to be of particular importance, for example in cases where future excavations are planned, or when we consider that they might be under threat from vandals or endangered by development. The latter includes the natural growth of Red Sea towns and cities, modern mining and quarrying, and construction of tourist facilities. We require somewhat more gear for this kind of surveying. To draw accurate plans we previously used tape measures and compasses. This method was quite tedious and prone to errors as we became fatigued. Later we could afford to purchase a theodolite (Fig.5.1), a rather simple piece of surveying equipment, from which we took elevation, and distance measurements of the buildings we sought to draw plans of, or, most recently, we borrowed a total station (Fig. 5.2).

The total station is an expensive piece of gear with a built-in computer and laser range-finding system. While one person operates the total station, one or more additional team members hold reflective prisms attached to poles over the points that must be measured. The laser beam emitted from the total station, which is set at a known and fixed point on the site, reflects off the prism and back to the total station, which records precise distance and elevation. All the thousands of ‘points’ taken during a site intensive survey are then downloaded into a computer which ‘draws’ a plan or map of the site. We can also add contour lines. Unfortunately, we have been unable to use the full power of the total station on our surveys. Since this device runs on batteries that must be recharged every four to eight hours, and our surveys are out in the desert far from any electrical grid for days or weeks at a time, we hook it up to a portable solar panel to provide—adequate sunlight and lack of cloud cover permitting—electrical current to the total station. Unfortunately, the solar panel while hooked up to the total station, cannot, at the same time, run the data notebook, which, ideally, would simultaneously record the various points for subsequent quick downloading onto a computer. Thus, we must write down by hand all the points (usually at least three sets of numbers per point) in a notebook; this is a laborious, time-consuming, and error-prone method. Still, this is more accurate and faster than using tape measures and compasses or a theodolite.

Fig. 5.1: Working with the theodolite at Berenike.

Fig. 5.2: Working with the total station at Sikait.

Another very useful technique that one can use in a site intensive survey to determine what walls or other features might lay below ground surface is ground penetrating radar, which is also known as magnetic surveying. This method is used when we want to have some idea of the features beneath our feet to determine where we might optimally place our excavation trenches to achieve the best results. This technique involves laying out a grid over a portion of a site and traversing it at fixed distances with special equipment. The radar sends back signals of varying strength depending upon the density of the material from which it is reflected; walls and other potentially man-made features built of stone or brick appear differently on the screen than does the looser and less dense soil that has accumulated around them over the centuries. Drawbacks to using magnetic surveying in the Eastern Desert are that most commercially available gear cannot penetrate beneath the ground surface deeper than about a meter or a meter and a half. If the site had a long history of habitation and numerous structures were built atop one another, then the radar will send back a very jumbled image of the various features off which it has been reflected. This frequently causes more confusion than clarification.

Of course, both intensive and extensive surveys might be combined into a single project, as we have done on a number of occasions. It is often a good strategy to maintain peak efficiency in a survey crew to take a break from one type of surveying and switch to the other.

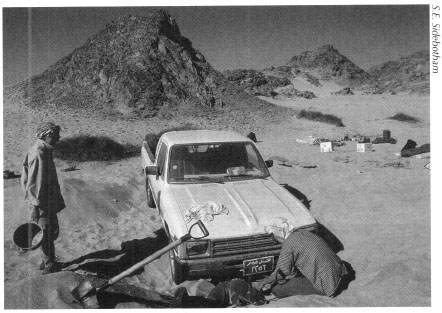

The surveys we conduct in the winter are usually less exhausting than those we undertake in the summer. During winter surveys we can also stay out in the field longer as we need to carry and use far less water than in the summer, when we drink an average of four to six liters per person per day. If you add water for cooking and occasional minimal bathing then this equates to about ten liters per person per day. A liter of water weighs one kilogram. Thus, three of us on a two week survey consume about 420 liters of water or twenty-one jerry cans. The water, plus gasoline, food, and other gear completely fills up the back of a Toyota Hilux pickup truck, the most ubiquitous vehicle in the Eastern Desert and the one that we have used for the majority of our desert survey work over the years.

Refueling the truck is simple. We insert a siphon into one of the gasoline jerry cans, which has been placed on the top of the truck, and suck on it as if using a large straw. Once the flow of gasoline starts (you always get a little fuel in your mouth with this technique) you place the other end of the siphon hose in the gas tank. If you are not feeling up to tasting a little eighty or ninety octane gasoline, you can always use our alternate method of refueling: pour the contents of the jerry can directly into the tank. This is best done by cutting off the top of one of those commercial plastic bottles containing drinking water and using it as a funnel to facilitate pouring the fuel into the tank. We have found this technique quite effective and in so doing, have discovered yet another one of the many uses for an empty plastic water bottle. It is interesting that while we foreigners prefer the latter technique, most of the Bedouin prefer the siphon method.

If the survey is a site extensive one our small team does not use tents in either the summer or winter. We sleep on small rollup mattresses, using sheets in the summer, and sleeping bags and blankets in the winter. In both summer and winter we cook over an open fire. If we are conducting a site intensive survey and are not more than about one hundred kilometers’ round trip from a town, then the vehicle can make forays to bring water, food, and other items as needed. In this situation we often cook on a small gas stove and in winter we will pitch tents, since it can be incredibly cold at night. On one survey farther north in the Eastern Desert in winter 1995 it was so cold one night that the water on the tops of our canteens froze. In the summer we will store our gear out of the sun, often in tents with flaps open to allow some air circulation. As long as the sun is up, we pitch shade tents, which look like giant beach umbrellas, under which we eat, do our paperwork, and study our finds. In the summer we sleep out in the open as it is simply too hot to be inside a tent.

On our surveys, if we are lucky, our Bedouin guides will make us fresh bread. Most prefer to make gurs/gaburi though if we are very lucky, they will make rudaf/marduf. Both types are unleavened and simply produced using only flour, salt, and water. Gurs is easier and faster to make. Mixing the flour with salt and water and working the dough on top of a piece of cloth, the resulting pizza-shaped concoction is then placed atop burning embers (the best are of acacia wood, but any flammable dried branches will do), which have been placed in a slight depression in the sand. The entire concoction is then covered in sand and embers and ‘bakes’ for about fifteen minutes after which it is turned over to bake for another quarter of an hour. The bread is then taken from the sand, beaten, and scraped to remove as much sand as possible and eaten. We love this bread and it is very tasty with cheese (feta) or peanut butter. Those Bedouin who are not as adept at making gurs tend to leave too much sand on or large pebbles in the bread. This can have serious consequences for your dental work. Another type of desert bread that we do not eat as often is rudaf (the ‘Ababda Bedouin term) or marduf (the Ma‘aza Bedouin word). This is more time-consuming to prepare and is usually produced for celebrations and special occasions. It is made in a similar fashion as gurs, but is somewhat chewier as there is a higher ratio of water to flour in the dough. This pizza-shaped dough is also deposited in a hole in the sand at the bottom of which are large pebbles or small cobbles that have been heated by fire placed above them. The dough is slapped directly atop these hot stones, covered with sand and baked.

Some of the More ‘Interesting’ Surveys

We will relate here a sampling of some of the more interesting surveys we have conducted over the years between 1987 and 2004. As might be imagined, many of our desert forays have had their share of problems. Occasionally ‘guides’ have gotten us lost and failed to find the sites for which we were searching. Frequently our survey vehicles became stuck in the sand for periods ranging from half an hour up to three days. Often critical parts of vehicles fell off or were seriously damaged and on one of our early surveys fire consumed our vehicle. Broken windshields, defective engine parts, non-functioning gasoline gauges, more flat tires than we had spares for, intense heat and cold, and other ‘inconveniences’ have also hampered our efforts. In addition, we have had moments when we realized that the fancy total station we brought out did not work and had to scramble to save the survey from being a total loss. Other issues such as spoiled food or running low on food, while critical, were not dire; we simply adopted the Eastern Desert diet plan: we didn't eat!

Many of these incidents required lengthy hikes on foot back out to the nearest paved road to seek help or led to ingenious and, in some cases, probably previously untried methods to solve particular problems or make vehicle repairs. Fortunately, none of these problems caused injuries to any of us.

The Burning Land Rover Survey, January 1989

This was one of our earlier surveys in the Eastern Desert and the one that came the closest to total disaster of any of the dozens of surveys we have conducted. The Land Rover we had obtained in Cairo from the American Research Center in Egypt was notorious, among those of us who knew it, for being extremely unreliable and temperamental, but it was readily available and extremely affordable to rent. Invariably it had to be pushed by several people to get it started, something not easily done in the desert; while in the desert we often parked it facing downhill to make the ignition process easier. On the morning of January 24, 1989 we were surveying along the ancient Roman road joining Abu Sha‘r on the Red Sea and the nearby Roman quarries at Mons Porphyrites on the one hand with the Nile on the other. We were just west of the Roman praesidium at ai-Heita when we stopped to examine a length of Roman road and some route-marking cairns. The three of us climbed back into the vehicle. The driver (Sidebotham) started the engine; bare wires beneath the dashboard started to glow red and ignited. The flames spread quickly and, realizing that it was an electrical fire, we disconnected the battery cables beneath the hood in an attempt to stall the fire, but all to no avail. We jumped out of the vehicle and tried to save as much of our gear as possible. We also threw jerry cans of gasoline, kerosene, and motor oil together with food and our water supplies out of the back of the blazing Land Rover. We then ran from the vehicle fearing that it might explode. It did not, but it burned furiously, creating an especially impressive black smoky fire when the spare tire attached to the hood ignited.

Leo A. Tregenza, born in the small Cornish fishing village of Mousehole, near the larger and better known town of Penzance, came to Egypt to teach school in the Upper Egyptian town of Qena in the 1920s. During his summer vacations in the late 1940s he made extensive trips lasting several months each into the Eastern Desert on foot and camel. He lovingly recorded his experiences in two books, The Red Sea Mountains of Egypt and Egyptian Years. He also published a number of articles on ancient remains, inscriptions, and birds of the Eastern Desert. He was the last of this generation of travelers to the region prior to 1960. Born the year Queen Victoria died, 1901, Leo himself passed away in 1998.

The survey architect stayed behind to gather and protect the gear we had salvaged while the Ma‘aza Bedouin guide and the other team member (Sidebotham) started the long walk out-as it happened we later measured it to be thirty-seven kilometers-to the paved road that links Safaga on the Red Sea to Qena on the Nile. The two of us each carried about four liters of water, which we had completely consumed long before we reached the highway. Hitching a ride to Qena, we headed to the police station to file a report and to seek help. The police took the report, but they were not interested in helping; they indicated, despite the possession of all the required permits, that we should not have been out there in the first place. Thus, we looked around the garage and vehicle repair district of Qena and we eventually found and hired a driver with his large truck to go back into the desert to haul out the burned hulk; this was no easy task as we had to lie to the driver about how close to the paved road the Land Rover was; he did not want to drive deep into the desert. If it had been up to us we would have abandoned the Land Rover in the desert where it had burned, but we had been told by the American Research Center in Egypt, when we phoned them from Qena about the accident, that we had to tow it to Qena as the vehicle had special ‘customs’ license plates on it and had to be accounted for. We spent parts of two days hauling the burned remains out of the desert and back to Qena. Steering it while being pulled by the larger truck was daunting as an incredible amount of ash blew back into the windowless cab. The driver (Sidebotham) wearing a knit hat pulled down over his eyes to limit the amount of ash hitting his face allowed him, with extremely limited vision, to steer the Land Rover, which was tethered close behind the larger truck. The tow rope periodically broke and with each repair, it became shorter and the towing more difficult. At one point the large back bumper of the truck around which the tow rope was attached fell off. We had to find another portion of the truck to attach the rope. In addition, clouds of sand and dust further limited visibility and made the ride one from hell.

One might rightly ask why we did not have two vehicles on survey as a safety feature precisely for such an eventuality. As always, our funds were extremely limited and we could not afford a second vehicle. This is frequently the case with many of the surveys we conduct.

The upshot of this particular incident, once we coaxed the truck driver to haul the incinerated skeletal remains into Qena, was removal of the remnants of the Land Rover onto a second vehicle, a large flatbed truck, which conveyed it to Alexandria. The Land Rover was then placed on a boat, taken out into the Mediterranean to Egypt's recognized national maritime boundary, and unceremoniously dumped into the sea. Apparently this type of disposal of vehicles is common and as we understand it, a large artificial reef has formed in this part of the Mediterranean as a result.

After the fire, we recovered what we could of our gear that we had wisely chucked out of the back of the Land Rover, hired another Ma‘aza Bedouin and his trusty Toyota Hilux pickup truck, and continued our survey. About a year and a half later when we were once again in the vicinity of the fire, we drove over to the spot. There, still lying melted into the sand, were aluminum bits of the Land Rover; we collected some pieces as souvenirs.

A DESERT SURVEY WITH NO WINDSHIELD:

JULY 1991

Sometimes problems develop before a survey, but one tries to minimize them and continue on. This happened in July 1991, as Sidebotham's diary entry recounts:

“While we were excavating at the late Roman fort and early Christian site of Abu Sha'ar north of Hurghada, I gave everyone a mid-dig break of about a week. Some staff opted for a trip into Luxor to see the sites, others stayed in our small flyblown and frequently waterless hotel in Hurghada to rest and catch up on paperwork. I headed out for a survey of some of the ancient sites farther south, especially those along the ancient Berenike-Nile road. Departing Hurghada after a full excavation day I topped off the gas tank of the project's Land Rover, this one rented from the Canadian Institute in Cairo, at Quseir and drove south on the coast road. Not far south of Quseir a passing truck, probably carrying gravel, drove by and a stone hit the driver's side of the Land Rovers shattering the windshield. I was unharmed, and after stopping to inspect the damage, drove on to Marsa ‘Alam where I would rendezvous with a second vehicle with driver and a guide. I tried to get the windshield replaced in Marsa ‘Alarn, but Land Rovers are not that common in Egypt and the nearest place I was told I could get a replacement was in Cairo. Clearly the survey would go forward in the desert without the windshield.

Throughout the desert survey, the broken windshield proved more of a problem than I had anticipated. I had to wear ski goggles or sunglasses to minimize the wind, dust, and sand that got into my eyes; my nose, ears, hair and everything else were caked in sweat mixed with sand and dust at the end of each day. Driving the Land Rover was miserable. Exacerbating the problem was the force of the wind coming through the broken windshield. It was so great that it broke the interior door latch so the door on the driver's side was constantly blowing open when I drove the vehicle even at minimal speeds. To solve this problem I tied a rope around part of the door near the handle and ran it over to the other door on the passenger's side and tied it there. It was not only uncomfortable to lean back into the seat with this rope running across my back, but every time I wanted to get out of the vehicle to do survey work, I had to untie the elaborate knot system I employed to keep the door shut. Despite these problems, the five-day-survey was a great success and I saw a number of sites that we would return to in later years to study in some detail. It was some weeks, however, before we managed to get a replacement windshield from Cairo.”

Stuck in the Sand for Three Days: The Aborted January 1999 Survey

In addition to problems with the survey vehicles themselves, there is the omnipresent danger of the survey vehicle becoming stuck in soft sand. This can and does occur with some regularity even to the most experienced Bedouin driver who knows the desert well. To us non-Bedouin working in the area, this happens frequently, but we can often extricate the vehicle after pushing and digging around the tires. Usually we are stuck for no more than half an hour to a few hours at most. A scheduled three-day survey involving four of us in January 1999 would be one that none of us would ever forget, but not for any reasons we had anticipated at the time.

We were conducting excavations at Berenike on the Red Sea coast that winter and always used days off to conduct surveys. This particular survey had as its objective to study and record more accurately some of the ancient praesidia that lay along the Ptolemaic and Roman routes linking Berenike to the Nile. Since three of the participants had never seen the fascinating ancient settlement of Ka‘b Marfu‘, we decided that a brief visit might be a good idea; it was right on the way to the other sites we planned to study. We tried to drive our heavily loaded, but underpowered, Toyota Hilux pickup truck up a hill to reach Ka‘b Marfu‘, but became mired in the sand with the vehicle facing uphill. We did not think much about it, and we went ahead and walked the short distance to the ruins at Ka‘b Marfu‘ where we had a nice visit; we returned to the vehicle at about noon.

Try as we might, we could not get the Toyota out of the sand; we dug, placed stones under the wheels so that they could gain traction, and even unloaded everything from the back to lighten the vehicle and make it easier to move. Nothing worked. We realized by the end of that first day that we would be lucky to get the truck down to flat ground by the next day.

We spent all of day two cajoling the vehicle down the hill to flat, but also very sandy ground. By this time our gear including jerry cans of gasoline, water, food, sleeping bags, and camera equipment was scattered all over the place and we spent a miserable day from about 7:30 in the morning until sunset trying every trick we had collectively learned over the years to get the vehicle out of the sand. At one point in the afternoon large black ravens or crows began to circle overhead, an ominous sign we thought, and then out of no where a little ‘Ababda Bedouin girl wearing a bright lime green dress, carrying orange flowers and herding four goats walked by. She did not have much to say and continued on her way. Her appearance was surreal.

It was fast becoming clear to us that using smaller stones to provide traction for the mired Toyota was not working so we looked for larger ones. These could be found only some considerable distance from the truck and required that we use ropes to haul them; we were so desperate that we even dismantled nearby ancient, but fortunately previously robbed, graves to use their stones. We assuaged our guilt, however, by photographing the tombs before ‘borrowing’ parts of them. But even portions of these funerary monuments failed to free the vehicle from the sand. So day two ended in frustration and disappointment with the realization that our water and food supply was running dangerously low. We had not planned on undertaking heavy manual labor from sunrise to sunset, which resulted in a much greater consumption of our drinking water than we had planned to use in the course of our normal winter survey work.

That night was cold and damp and more or less reflected our spirits. We had the car on flat ground, but we still had to turn it at least ninety degrees so that it faced away from the hill on which we had been initially stuck. On the third day of our ordeal, we had to turn the truck around somehow. The only way we could accomplish this was by digging massive holes around the truck, elevating it up using the car jack and then pushing it off the jack (Fig. 5.3). In this way we slowly turned the Toyota around. This we did all day: digging, elevating, and pushing it off the jack. It was exhausting. At about 10:45 AM an ‘Ababda Bedouin man accompanied by a donkey and a dog appeared. We do not know if he was related to the girl we had encountered on the previous day and we really did not care. He was quite free with his advice on how to get the truck unstuck, but not inclined to help otherwise; we were not impressed as we had already tried and failed using the methods he proposed. He wandered off. Finally, we managed to turn the vehicle so that it faced toward flat ground. We then built a lengthy and elaborate road of stones and boulders that was slightly wider than the width of the truck. Many of the stones and boulders we lifted from areas where we had used them on the two previous days; others we dragged from farther afield. By building this road, which, we thought, closely resembled one of its Roman ancestors in Europe, we had constructed in our eyes, an engineering marvel, but one that required all our energy. With one last effort, three of us pushed as hard as we could while the fourth drove along the length of our stone highway. We built up enough speed and finally we were free! It was 3:20 PM of the third day, January 20, 1999. We loaded the gear, which we had to carry several hundred meters to the Toyota, and headed back to Berenike. Upon arrival sometime after 8 PM that night the rest of the staff at the dig asked about the survey. One can imagine what we had to tell them. We discovered only later that the constant strain of elevating of the truck and pushing it off the car jack had resulted in a serious fracture to one of the main struts of the vehicle. If this had broken while we were attempting to extricate ourselves from the sand we would have been in dire trouble. It is a good thing that we did not know this while we were still stuck in the sand as this knowledge would only have added to our worries.

We passed by the area where we had been stuck about a year later and portions of the huge holes we had dug in the sand to free our vehicle could still be seen. Needless to say, subsequently we found and bought a pair of ‘sand ladders.’ These are long pieces of corrugated steel with large round holes punched through them at fixed intervals. They proved very useful in later incidents in extricating us relatively quickly and easily from the sand.

Fig. 5.3: Stuck in deep sand near the ancient settlement of Ka‘b Marfu‘

The Hottest Survey We Ever Had: Summer 2001

In July and August 2001 we continued a site intensive survey that two of our team members had started in winter 2000: drawing a detailed plan of the large and impressive Roman emerald mining settlement in Wadi Sikait. The goal was to complete drawing a plan of the site and check what had been drawn in winter 2000 for accuracy; we also hoped to draw architect's elevations of several of the larger and better preserved structures, including two rock-cut temples. We then intended to move our camp north up the wadi to draw plans of two other emerald mining settlements, which we named Middle Sikait and North Sikait. The team started off with five people, two of whom had spent about forty days in winter 2000 drawing a site plan of the main settlement in Wadi Sikait, which they did not finish. We had no illusions about the nature of the survey and anticipated the usual summer desert heat, but we were not prepared for what we in fact had to face: the most grueling survey any of us had ever endured.

The ancient settlement in Wadi Sikait nestles in a relatively narrow defile surrounded by mountains. This not only prevents much, if any, wind or breeze from entering the wadi, but it also retains the heat very efficiently, more so than in a flatter, more open place. In addition, the heat soaked up by the ground and surrounding mountains then radiates off them at night making the wadi miserably hot twenty-four hours a day. Our normal routine was to awaken at sunrise-which was about 6 AM—eat, and move out quickly with the total station, solar panels, and prisms and survey as much as possible before the incredible heat built up, which was usually sometime between 11 AM and noon. We would then retire to our shade tent, eat, rest, attempt to read, and vegetate during the hottest part of the day until about 3 PM. During those listless hours the heat was unbearable. The bindings in our paperback books became so dry that the pages fell out. The glue holding the nozzles on our camping shower bags (which were kept in the shade during daylight hours because of the intense heat caused by direct sunlight) melted and the nozzles and hoses fell off.

None of us had a normal weather thermometer, but someone brought a thermometer used to measure human fevers. We will never know how hot it actually got during those blistering afternoons because the thermometer did not register above 42°C (108°F), but we were able to measure the coolest temperatures. The air temperature never got below about 34°C (94°F) and that was at 2 or 3 AM. The ground temperature was much hotter and it was on the ground that we slept, or tried to. Sleeping was difficult. Usually we hauled our sleeping mattresses out from under the shade tent soon after the sun went behind the mountains, at about 6:00 PM. It was then that we ate dinner and bathed, if there was enough water. We usually rested on the mattresses for about thirty to sixty minutes and then had to move them as the heat radiating off the wadi floor was retained beneath the mattresses while the surrounding wadi floor became cooler. Thus, a good part of the night was spent moving mattresses every hour or so to try to find ever cooler spots.

When we had adequate water we looked forward to showers, again, only after the sun went behind the mountains at the end of the day and the scalding water in the shower bags had cooled down somewhat. One of us proudly rigged a shower bag on one of the tripods we used to mount the total station. The others went behind nearby boulders to wash. We drank so much that we could hear the water sloshing in our stomachs, but we were always thirsty. The esprit de corps was wonderful and although two team members had to leave before the end of the survey, we are all understandably very proud of the work we did over those three weeks or so; we formed a bond that will last a long time. We can also never thank our ‘Ababda Bedouin friend enough for bringing out to us every three or four days desperately needed water, food, and the occasional surprise snacks.

There are many other stories we could recount about our desert surveys, but these four should provide some insight into the trials and tribulations that might occur while conducting this important archaeological work. Not all surveys were as plagued as the ones described above; some have actually taken place without a hitch, but you must be prepared for anything to happen in the Eastern Desert and try to accommodate the best way possible.