The Necessities of Life

CLOTHING

THERE WAS NO ‘NAVAL UNIFORM’ in the seventeenth century. A commissioned officer would be distinguished above all by his sword, and probably an elaborate baldric. In battle, many wore partial body armour; Lely’s portrait of Vice-Admiral Sir William Berkeley (1639–66) shows him wearing a somewhat battered breastplate, probably worn during the battle of Lowestoft that the painting commemorated.1 Otherwise, officers wore whatever they wished. The Duke of York went to sea in 1665 in a buff coat and a protective metal skull cap covered in black velvet.2 Most of those whose portraits were painted are shown wearing military-style tunics or silk coats, but Sir John Harman wore a Persian-style long coat for his portrait, and the ever-flamboyant Sir Robert Holmes opted for a turban.3 It is unlikely that such exquisite costumes formed part of their day-to-day shipboard attire, although one gentleman captain was supposed to have come on deck in ‘his silk morning gown and powdered hair’ when his suspiciously undamaged ship returned to port after a major battle.4 The wardrobe of Captain William Botham, who died in 1690, was more prosaic and probably much more typical: it included nine old coats, six pairs of britches, thirteen waistcoats, sixteen pairs of stockings, eight pairs of socks, three pairs of drawers, twenty-one shirts, a morning gown, three old hats and a pair of slippers. The only items of clothing that gave any clue to his profession were ‘six sea neck-cloths’.5

Pursers and slopsellers traditionally sold clothes to the men ‘without any restriction as to their sorts, proportions and prices’, a custom leading inevitably to corruption. There was an attempt at some standardisation in 1655, when an outfit and prices were specified: canvas jackets (1s 10d each), canvas drawers (1s 8d), cotton waistcoats (2s 2d), cotton drawers (2s), shirts (2s 9d), shoes (2s 4d a pair), linen and cotton stockings (10d a pair).6 More precise regulation was attempted in the General Instructions to Captains of 1663: ‘Monmouth caps, red caps, yarn stockings, Irish stockings, blue shirts, cotton waistcoats, cotton drawers, neats leather, flat-heeled shoes, blue neckcloths, canvas suits, blue suits, rugs’. Under the new regime, a committee of the captain, master, boatswain and gunner would rate the clothes ‘at the mast’ and set a reasonable price for them. This had to fall within the maximum prescribed by the instructions, such as 2s 6d for a Monmouth cap and 5s for a canvas suit.7 Thus in practice, and although there was no formal uniform per se, a ship’s company would have had a reasonably uniform appearance, in which the colour blue would have been prominent; the clothes delivered to the Greenwich in 1678 included 132 blue shirts (and only thirty-six white ones), twenty blue suits and thirty red caps.8 Uniformity should also have been a consequence of the centralisation of supply. In 1666 Thomas Beckford was appointed slopseller to the navy. Like Pepys, whom he befriended, he was the son of a tailor, and he later became master of the Clothworkers’ Company. He was suspended in 1675 following allegations that he had ignored the regulations and sold clothes at above the specified rates, but he was eventually able to clear himself and, indeed, received a knighthood a couple of years later.9

FOOD AND DRINK

The seamen were entitled to a gallon of beer a day, and in smaller ships, at least, this seems to have been served by ladle from a barrel. They were also meant to receive a pound of biscuit a day, and over the course of a week they could expect four pounds of salted beef‘of a well fed ox’, two pounds of pork, three-eighths of a fish, a quart of peas, six ounces of butter and twelve ounces of cheese.* Corrupt pursers had various means of serving up slightly less than the allowance and pocketing the difference.10 Even so, the full amount was still ample, though even at the time some criticised its nutritional value; but seamen were said to be ‘besotted in their beef and pork’, and simply refused to embrace healthier alternatives.11 There were several variations to the regular victualling allowance. A different diet was provided in the Mediterranean and on other overseas stations, with wine in lieu of beer, raisins or currants in lieu of beef, rice or stockfish in lieu of cod and olive oil in lieu of butter or cheese.12 Barlow was scathing about this diet, especially the sour ‘beverage wine’ that he blamed for laying low many men with the flux.13 The official victuals could always be supplemented by locally acquired supplies of vegetables and fruit, as well as by fishing, and ships also frequently carried live fowls and animals. Petty warrant victuals were provided for ships in harbour. Barlow was equally blunt about their quality, denouncing the ‘little small beer, which is as bad as water bewitched’, the poor brown bread and some old, tough beef, ‘when all the best was picked out, leaving us poor seamen the sirloin next the horns’.14 If a ship’s supplies were running low, captains could put the crew on short allowance, a reduced diet (four men’s rations between six) for which the men were meant to receive a rebate.

Short allowance invariably generated grumbling. John Baltharpe, the poetic seaman aboard the St David in 1670, encapsulated the feelings, and could not resist a dig at the substantial fare that captains continued to enjoy when short allowance was imposed on the rest of the crew:

I know the king far better doth allow,

But how to compass it, we do not know,

For mutineers, we will be never,

If that we keep but life and soul together.

Captains few there are, which thinks on this,

When they have daily each thing which they wish.15

Sir William Berkeley; part of the ‘flagmen of Lowestoft’ series painted by Sir Peter Lely. Berkeley was killed during the Four Days’ battle of 1666.

(NATIONAL MARITIME MUSEUM, GREENWICH)

Captains certainly did have ‘each thing which they wish’. They often brought aboard their own provisions, had their meals cooked separately, and frequently laid on meals for their own or visiting officers that resembled grand banquets ashore. The naval chaplain Henry Teonge recorded with relish the menus of some of the meals that he experienced. On 10 July 1675 his captain entertained the other captains of their squadron with four separate meat courses: hens and pork boiled together; mutton and turnips; eight ribs of beef, ‘well seasoned and roasted’; ‘a couple of very fat green geese’; and a Cheshire cheese. This was washed down with ‘Canary, sherry, Rhenish, claret, white wine, cider, ale, beer, all of the best sort; and punch like dishwater’.16 Christmas Day brought beef, plum pudding and mince pies; the king’s birthday was the excuse for veal, mackerel, lobster, salad and eggs. Rather less extravagant fare was provided on other days, but even so it was clearly substantial (and substantially better than that available to the crew).17 Toasting was an essential daily ritual, and this frequently became the basis for frenetic partying; the officers of Teonge’s ship, the Fourth Rate Assistance, must have spent much of late May and June 1676 in a contented alcoholic haze, celebrating one birthday party or wedding anniversary after another.18 The need for captains and admirals to promote the country’s image by entertaining as liberally as possible was condoned by the administration, and even gained official endorsement. From 1673 the purser of the fleet flagship was given an additional allowance to provide port, beer and bread for all the entertaining that an admiral was expected to undertake.19

Eight men from each of the two watches formed a mess, so that half of them would be on duty at any one time, creating more space for the other half. Belongings were stowed in sea chests. On the Assistance in 1675, each mess was allowed to keep two chests on deck; most men seem to have brought their own on board, but most were staved to reduce clutter ‘lest they trouble the ship in a fight’.20 Each mess had its own table, usually between two of the guns, and this was where meals were eaten off wooden bowls or pewter plates, though the latter were often confined to the officers alone.21 It is not entirely clear how meal times were organised, even a century later, as the fact that there was one set meal time for the entire crew must have imposed huge pressure on space. Earlier in the century, Sir Henry Mainwaring suggested that the boatswain allocated men to the messes, but it is possible that the men themselves also had some choice in the matter, within reason, as did their counterparts in later years.22 Men were entitled to ‘necessary money’ of 6d a day to provide themselves with wood, candles, plates and spoons, but this was insufficient to cover all their requirements, and pursers colluded with the men’s extravagant demands for such items, lining their own pockets in the process.23

HAMMOCKS AND BEDS

Until the early decades of the seventeenth century, men slept in cabins, which, according to one contemporary, were ‘no better than nasty holes, which breed sickness, and in a fight are very dangerous’.24 Hammocks were in general use for overseas service by the 1620s, but it took another two or three decades for them to become the standard form of bedding in home waters. Three thousand hammocks were delivered to the fleet in 1666, presumably as spares, and by the 1680s First Rates were being issued with 1,000 hammocks for 780 men, permitting one for each man with a reasonable stock left in reserve. Men provided their own mattress, pillow and blankets, or else bought them from the purser; these fitted into the hammock at night and could be rolled up in it and stowed away during the day. Space was very limited. In the eighteenth century, each man was allocated a space fourteen inches broad for his hammock, and even allowing for the fact that one watch would usually be on deck, this must have involved some ingenious feats of space management, especially as seamen’s mattresses were over two feet wide.25

HEATING, VENTILATION AND LIGHTING

Heating below decks was rarely necessary. Most of the great ships were deployed only in the summer, and the majority of the frigates in service during most of the peacetime years of the period were deployed in the Mediterranean; the enforced huddling together in a confined space of large numbers of men would also have kept things warm enough. However, heating was an issue for the skeleton crews of the ships laid up in ordinary, who had to use fires between decks without endangering the ship. The same risk attended lighting, which had to be done by candles and lanterns, and the General Instructions issued to captains from 1663 onwards specified that once the night watch was set all fires and candles had to be extinguished.26 Ventilation gratings were placed along the centre line of each deck, where they did not interfere with the guns. Otherwise, the only effective method of ventilation was to open the gunports, but this was clearly not always practicable in certain sea or weather conditions, and ships closed up in this way must quickly have begun to stink below decks (especially as the same conditions would entail men coming off watch in wet clothing,‘for there is nothing more unwholesome at sea than to sleep in wet clothes’, as one commentator noted).27

SANITARY ARRANGEMENTS AND CLEANING

Waste disposal could be a serious problem aboard a large ship. Indiscriminate use of the deck would lead to everything flowing into the bilges, which stank at the best of times, and was a sure recipe for disease. The decks seem to have been cleaned at least occasionally,* and in 1673 thirty tons of vinegar were delivered to the fleet ‘to wash their decks, to keep their men in health’.28 During the Restoration period, too, several refinements were made to the sanitary arrangements aboard warships. From about 1670 onwards, the warrant officers obtained ‘roundhouses’ at the stern, similar to the more private ‘quarter gallery’ that the captain had always enjoyed, though at least some, like Henry Teonge, provided themselves with chamber pots.29 Seats in ‘the heads’ were also introduced during the same period; these were simple rectangular boxes. A ‘pissdale’ or urinal stood on the upper deck, abaft the forecastle bulkhead.30 Even so, in a large, crowded ship it must have been difficult at times for men to reach these destinations or the easier, traditional alternative, the ship’s rail on the lee side. The likelihood that men relieving themselves between decks was a problem is suggested by the fact that a regulation was brought in specifically to address it: ‘he that pisseth between decks, or otherwise easeth himself, either there, or in any other place’ was to receive up to twelve lashes at the capstan.31

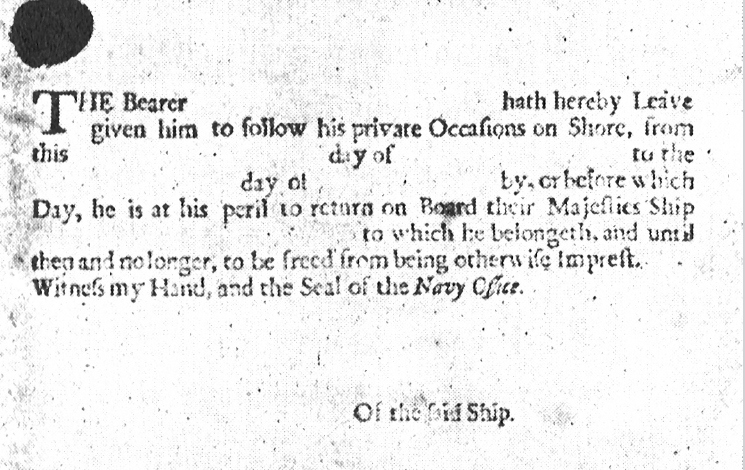

A printed ‘ticket of leave’ from the 1690s.

(PRIVATE COLLECTION)

* For the victualling system itself, and complaints about bad victuals, see Part Nine, Chapter 40.

* See Part Seven, Chapter 25, p135.