Dockyard Officers and Workforce

BY CONTEMPORARY STANDARDS, the manpower required by the dockyards was astonishing. The numbers of men employed at the yards varied greatly, depending on war, peace and money, but even in the darkest days of retrenchment the dockyard workforce far outdid that of the darkest mill, which rarely had more than fifty men. In 1654 it was ordered that the yards should employ no more than 980 men in total, but with war against Spain imminent, this can never have been more than an optimistic ideal.1 In the final quarter of 1671 Chatham, Deptford and Woolwich dockyards alone employed 1,613, but a year later, following the outbreak of war, the number had risen to 2,293. Peace led to swingeing levels of retrenchment. When the third Anglo-Dutch war ended in 1674, Chatham ropeyard lost almost half its entire workforce, including 238 shipwrights, while Portsmouth lost over half its shipwrights.2 In 1675 Chatham had 319 workmen, including 150 shipwrights; Portsmouth had 234, Woolwich 223, Deptford 178 and Sheerness thirty-two.3 The major building programme that was commenced in 1677 led to another expansion, followed after its completion by an even more drastic contraction: by the summer of 1685 Chatham, Deptford and Woolwich had only 672 employees between them, though another 396 were soon taken on.4 The vast increase in the navy’s commitments after 1689, and in the burden placed on the yards, can be judged by the fact that by 1694 Chatham alone was employing over 1,400 men.5

THE RESIDENT COMMISSIONER

The resident commissioners employed at Chatham and Portsmouth (and, briefly, at Harwich) were meant to act with the same powers as the entire Navy Board. This was the only sensible solution; distance made it impractical to refer urgent matters to the Navy Office in London, and the commissioners had to be given considerable latitude to use their own initiative. The resident commissioners were also able to make local purchases of materials, although for large contracts, they had to seek the Navy Board’s prior sanction or, in emergencies, its retrospective approval.6 However, resident commissioners were technically not superior to the senior officers of their yards, the master attendant, master shipwright, clerk of the cheque and storekeeper, all of whom answered directly to the Navy Board in London. Therefore, the commissioners could not order: they could only advise and cajole, a system that provided a guaranteed recipe for confusion and conflict. For example, the commissioners were meant to meet with the subordinate officers every morning between six and seven to detail the day’s work, but this did not always happen, primarily because the officers resented any oversight and infringement of their independence.7 They also had wide powers of supervision and discipline over their subordinate officers and the yard as a whole, and these were made more explicit in new patents issued to those appointed to the posts in 1686.8 Until the late 1660s, commissioners were usually experienced shipwrights, but the appointment of Captain (later Sir) John Cox at Chatham in 1669 signalled a change in favour of former sea-captains.9

The resident commissioners were usually outsiders, appointed deliberately to be aloof from the internal politics of the yards and their neighbouring communities. The exceptions that proved the rule were the Pett dynasty at Chatham, Woolwich and (to a lesser extent) Deptford, who were so heavily embedded throughout the Thames and Medway regions, at the heart of a remarkably complex system of family and patronage networks, that accusations of rampant corruption and cronyism were probably inevitable.10 However, appointing outsiders also had its dangers. Dockyards were inextricably bound up with the communities beyond their walls, and abounded with intricate kinship and friendship networks, petty jealousies, arcane traditions and obscure privileges. An abrasive commissioner could easily exacerbate an already delicate situation, and this was particularly true of Sir Richard Beach, commissioner at Chatham from 1672 to 1679 and at Portsmouth from 1679 to 1690. A no-nonsense old Cavalier who had been the most successful Royalist privateer captain of the 1650s, Beach was wholly incapable of suffering fools gladly, and clashed frequently with his subordinate officers (especially the deeply entrenched Petts), often reporting their deficiencies to Pepys or the Navy Board in the most colourful and uninhibited terms. They, in turn, attacked him for inflicting on them a ‘wicked and a hellish living’.11

THE CLERK OF THE CHEQUE

The service records of all who worked in the yards were the responsibility of the clerk of the cheque. He mustered the personnel, including the shipkeepers of the vessels in ordinary, at least once a day, and was meant to keep exact records of when men were entered and discharged. He drew up and kept the muster and pay books for the yard, sending them up to the Navy Board at regular intervals. He also oversaw the work of the porter of the gate and monitored the activities of the storekeeper.12 The office was an obvious career step for pursers or for those who had served as junior clerks in the yards. Given its supervisory nature, it afforded ample opportunities for malpractice to those who were so inclined; for example, collusion with pursers enabled the clerk to collect wages and victuals for nonexistent crewmen on ships in the yard.13

THE STOREKEEPER

The storekeeper received all stores into the yard and checked that they were of a suitable quality. Timber had to be measured exactly and tested for defects. Having admitted goods into the yard, the storekeeper was then responsible for their preservation and the prevention of decay and embezzlement. He supervised the issue of timber, iron and all other materials to the other officers of the yard, especially the master shipwright. Because of the nature of the position, and the responsibilities that it entailed, the storekeeper’s instructions placed particular emphasis on his personal attendance at all receipts, issues and alterations, and on the need for him to keep detailed records.14

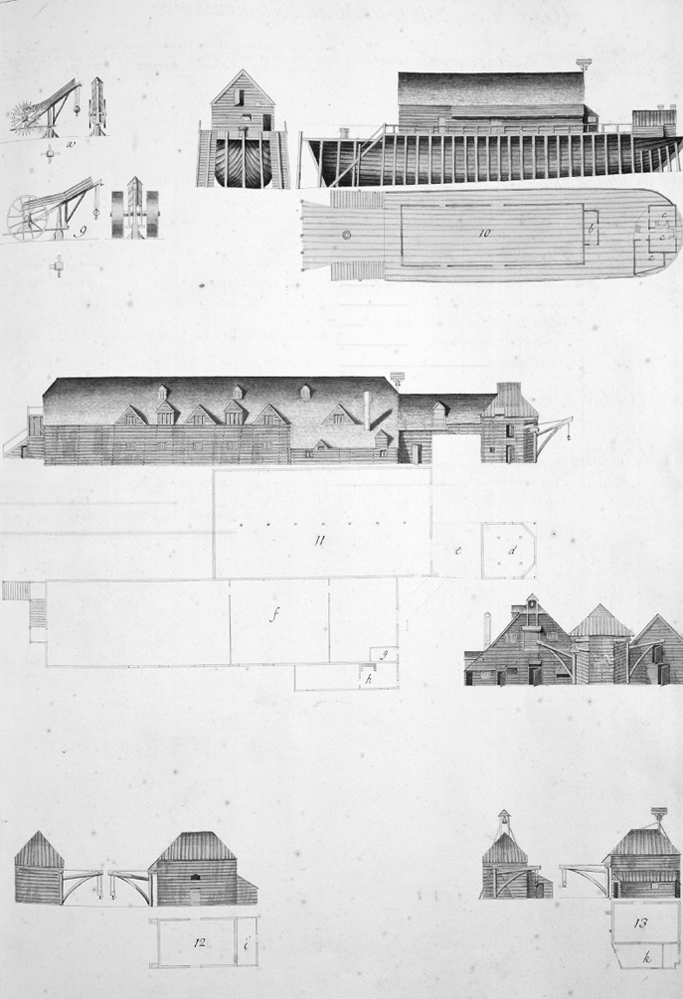

Many aspects of dockyard work were labour intensive. Several of the types of crane used at Portsmouth Yard in the 1690s are illustrated here; a hulk is shown at the top right.

(BRITISH LIBRARY, KINGS MS 43)

THE CLERK OF THE SURVEY

In effect, the clerk of the survey acted as a check on the other yard officers, for his duties empowered him to conduct joint surveys with them of the stores and other materials for which they had responsibility. He had particular responsibilities for the sails in the yard, for the quantities of stores issued to ships going to sea, dealing with demands from captains, adjusting accounts with ships’ boatswains and carpenters and overseeing the contents of the ships laid up in ordinary.15

THE MASTER SHIPWRIGHT

In some respects, the master shipwright was the most important officer in the yard, thanks to his responsibility for designing, and overseeing construction of, any new ships built there. However, he also had a wide range of more mundane duties to perform, including jointly overseeing routine maintenance, issuing and checking ship carpenters’ stores, assisting the storekeeper in checking the quality of stores received and supervising the shipwrights under his command, who constituted far and away the largest group of workers within each yard. The master shipwright had often worked his way up from an apprenticeship in the yard, and several were related to predecessors in the same role, a classic example of expertise being handed down the generations in the same families.16 Both of the sons of Jonas Shish, master shipwright at Deptford and Woolwich from 1668 to 1680, became master shipwrights at the yards in their turn. Phineas Pett, master shipwright at Chatham in the 1660s and 1670s, was the nephew of the commissioner of the same yard, and the commissioner’s brother was the master shipwright at Woolwich and Deptford; his grandfather Phineas had built the Sovereign of the Seas, and Phineas senior, in turn, was the son and grandson of shipbuilders and master shipwrights and brother or uncle to another three.17 Each yard also had an assistant master shipwright, who was often promoted to a mastership when it became vacant, either in his original yard or at one of the others. Woolwich had no master shipwright of her own until 1675, when the office was made independent of that at Deptford.18

THE MASTER ATTENDANT

The master attendant bore much of the responsibility for the ships in the yard. In particular, he took charge of their moorings and cables, commanded de facto all ships being moved within the harbour, jointly oversaw docking and graving, allocated pilots to incoming ships, issued rigging and boatswains’ stores to ships setting out to sea and checked them back in again on their return, oversaw the shipkeepers of the vessels in ordinary and had an overall responsibility for harbour security.19 There were joint masters attendant at Chatham until 1677, when only one was appointed (albeit with an assistant).20 The position of master attendant was an attractive career step for tarpaulin officers, although in practice the right of succession to the post traditionally belonged to the boatswain of the Sovereign as ‘first boatswain of England’.21 John Moore served as a gunner and boatswain before gaining his first command in 1665; he subsequently became master attendant successively at Portsmouth, Chatham and Deptford. Philip Lately, who became master attendant at Chatham in 1673, had been successively boatswain of the Henry, Royal James and Sovereign, then lieutenant of the Royal Charles and the Sovereign again.

THE CLERK OF THE CONTROL

This office was established in 1669, following the exposure of many deficiencies in record-keeping practices in the yards during the second Anglo-Dutch war. Francis Hosier, clerk of the cheque at Gravesend, proposed a series of reforms which centred on his own system of double-entry book-keeping; he claimed that this would permit a much more detailed itemisation of commodities, making it more difficult for stores simply to vanish. Pepys enthusiastically supported Hosier, who became the first clerk of the control at Deptford and retained that position until 1679.22 However, the office was abolished during the significant retrenchment that took place during that year.23

OTHER OFFICERS

Each yard had a porter of the gate, who was meant to set the watch, ensure accurate timekeeping by the workforce and prevent ‘tippling in alehouses or the porter’s taphouse’. He was also tasked with preventing abuses, such as the carrying away of excessive amounts of timber, and to carry out that duty he was specifically ordered to search men as they left the yard. It was a responsible position, and it attracted respectable men: Portsmouth’s porter from 1682 to 1684 was a veteran Cavalier and former captain of royal yachts, Thomas Crow, who had been accused of triggering the third Anglo-Dutch war by not enforcing the ‘salute to the flag’ on the Dutch fleet in 1671.24 The boatswain of the yard had responsibility for the ropes, wheelbarrows and other gear used by the labourers in the yard, oversaw the cleaning of the docks and supervised the disposition of all the small boats. He also allocated labourers to their duties each morning and appointed foremen. The ropeyards at Chatham, Portsmouth and Woolwich each had their own clerks, who oversaw the workforce and the supplies of hemp, as well as a master ropemaker. Each dockyard also had a master caulker (often a former ship’s carpenter), a master boatmaker, a master mastmaker, a plug-keeper (responsible for the dry dock gates) and a surgeon, while in the early part of the period Chatham and Portsmouth had look-outs.25 Although copies have not always survived, all of these officers, as well as the more senior ones, seem to have been issued with official instructions.26 These were sometimes ambiguous and permitted disputes over jurisdiction, such as that in 1663 when both the masters attendant and boatswains of the yards claimed the right to allocate labourers to their daily duties.27

OFFICERS’ PAY AND CAREERS

The five senior officers at Chatham, Deptford and Portsmouth, namely the master attendant and shipwright, the storekeeper and the clerks of the cheque and survey, received an income of £200 a year; those at Woolwich and Sheerness received £150. The master caulker and assistant to the master shipwright received £100 a year at the larger yards, £80 at the smaller, while the boatswain of the yard and the porter received £80 and £30 respectively at the larger yards, £70 and £25 at the larger. When Plymouth yard was established, rates of pay were initially set at the same level as Woolwich and Sheerness. The surgeon of the yard received £40 a year, except for at Chatham, who received £30, but this was supplemented by a mulct of 2d a day from the wages of those serving in the yard.28 Dockyard officers frequently complained that their pay was too small to support a family, especially when they received it so erratically. They also grumbled that the increase in their workload in the 1670s meant that they could no longer follow their own trades ‘on the side’ and were forced to resort to underhand means of enhancing their incomes.29 Unsurprisingly, the dockyard officers were often accused of rampant peculation; one of the first things that Pepys noticed about the yards was the suspicious neatness of the officers’ houses, and his fellow diarist Evelyn compared Commissioner Pett’s house at Chatham to a particularly exquisite Roman villa.30

A letter from Sir John Mennes, controller of the navy, to the clerk of the cheque at Chatham, complaining about the theft of a ‘great mast’ from the yard.

(RICHARD ENDSOR COLLECTION)

Officers often moved from one yard to another, and their dockyard service might be interspersed with periods at sea. Abraham Tilghman had been ‘instrument’ (or assistant) to the master shipwright at Chatham and storekeeper at Sheerness, then clerk of the ropeyard at Chatham, before being recommended for purser of the Prince in 1689.31 Shipwrights in the yards often went on to become carpenters of warships, perhaps returning to the yards later in their careers.32 Service at Chatham was unpopular with some, and officers sometimes tried to avoid being posted there; it was comparatively remote from the metropolis, but a clannish insularity in the Medway towns may also have bred a hostility towards incoming ‘strangers’.33

THE WORKFORCE: COMPOSITION

Each dockyard required a range of skilled men, and also sufficient unskilled workers to carry out the various manual tasks. In 1662, for example, Deptford was employing 135 shipwrights, thirty-one caulkers, five mastmakers, five boatmakers, eighteen ‘oakum boys, twenty-six joiners (who worked on ships’ internal fittings) and three sailmakers. But the yard also required men who could work on the buildings and other infrastructure ashore, so the workforce also included house carpenters, scavelmen (whose primary duty was the maintenance of the docks), a wheelwright, a plumber, a plasterer, a waterman, six bricklayers, eight sawyers, sixty-three labourers and nine seamen. Deptford’s ‘sister yard’ at Woolwich had no mastmakers or boatmakers, but unlike Deptford it had three blockmakers and a ‘grindstone man. Woolwich had just laid off its plumbers and plate workers, as there was no work for them.34 If a number of ships needed to be fitted for sea in a hurry, riggers were taken on. In the summer of 1688 the number of riggers at Chatham varied daily between about twenty-four and thirty, usually divided into three crews working on different ships and taking just over three weeks fully to rig a Third Rate.35 By custom, the carpenters of a ship paying off in a yard were entered on its books as shipwrights, and old seamen who lived in dockyard towns often sought places in the yards for their last years as a means of providing for their families.36

Men could be pressed for service in the dockyards, a practice that did not end until the reign of Queen Anne. The immediate hinterlands did not always furnish enough men, so the administration often had to look further afield. In January 1666 a shortage of shipwrights forced the administration to trawl the entire east coast of England, with mayors receiving requests to press specified numbers of shipwrights. Fourteen were requested from Yarmouth, twelve from Hull and ten each from Newcastle and Maldon; even comparatively small or decayed ports were called upon, with four being demanded from Blakeney and six from Walberswick.37 This frantic hunt for manpower, and the sheer numbers required by the dockyards during wartime, meant that the navy was calling on a large proportion of the skilled manpower available in the nation; in 1675 there were said to be 1,130 shipwrights and 120 caulkers in total on the entire east coast of England, of whom 598 and ninety-eight respectively could be found on the Thames between Gravesend and London Bridge.38 When men were discharged from the yards at the end of the war, there was no real principle of‘last in, first out’ and no recognition of the additional sacrifices made by men from outlying areas. The 315 men ordered to be discharged from Chatham in March 1674 were to be, firstly, ‘the pressed men and strangers’ (those not from the Medway area) and secondly, those who had the least pay owed to them.39 ‘Strangers’ included men from Bristol and Newcastle* and a few Dutch shipwrights, but the term might also include Deptford men send down to work at Chatham, and yard officers chafed at the arbitrariness of a rule which forced them to dismiss hard-working ‘strangers’ in order to retain idle and disaffected ‘townsmen’.40 Nevertheless, for the lucky few who were not discharged when every downturn took place, the dockyard could be quite literally a ‘job for life’. In 1674 the oldest shipwright at Chatham was seventy-fouryear-old Robert Podd, who had worked there for forty years, but even he had to cede seniority to the sawyer James Danks, who was seventy-six.41

THE WORKFORCE: PAY AND PERQUISITES

In 1650 wages for shipwrights were raised from 1s 6d to 2s 1d a day.42 Riggers, sawyers and members of some other trades got only 1s 6d, labourers got 1s 1d, and oakum boys got 6d. The foremen with the greatest responsibilities, those of the shipwrights and caulkers, received three shillings a day, as did the likes of the master mastmaker and boatbuilder.43 All of these rates were at least comparable with those in merchant yards. Working days were long; in the longer daytimes from April onwards, men worked for twelve hours from 6am until 6pm, though in winter they worked only from dawn until dusk.44 However, the standard hours and rates of pay were supplemented by elaborate overtime regulations, and these provided much-sought-after opportunities for supplementing incomes. Working a ‘tide’ of an hour and a half earned a man just under a third of a day’s pay, while a ‘night’ of five hours brought a full day’s pay.45 On 27 April 1670 it took seventy-seven men to shut the single dock gates at Chatham behind the Greenwich, a task that took them until 10pm; this entitled all of them to a ‘night’.46 From the administration’s viewpoint, ‘nights’ and ‘tides’ constituted unwelcome expense (in 1662, these overtime payments were said to form one third of the charge of the yards), and attempts were made to restrict them,47 though these were generally frustrated by the workforce, partly because at least some of each yard’s officers usually sympathised with their position.

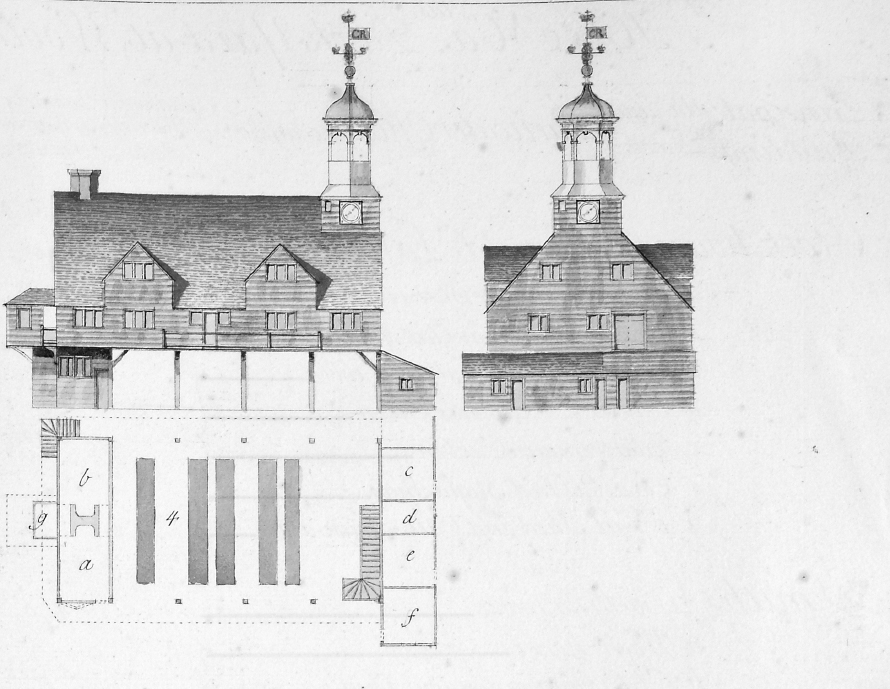

Similarly, breakfast and dinner times and holiday entitlements were jealously guarded. Men were allowed an hour and a half for dinner between April and August, an hour at other times of the year, and were entitled to a separate breakfast time of half an hour from February to November.48 Any attempt to interfere with the timing of these breaks was guaranteed to produce protests, although practice at the yards differed; workers at Chatham and Portsmouth breakfasted at their workplaces, those at Deptford and Woolwich did not.49 In addition to Sundays, dockyard workers had a number of holidays. New Year’s Day, 30 January (the day of humiliation for the execution of Charles I), Easter Monday and Tuesday, Whitsun Monday and Tuesday and the feast days of St Stephen and St John were full holidays on which men were not expected to work, while Shrove Tuesday, coronation day, the king’s birthday and 5 November were half-days for which men received a full day’s pay.50 The upshot of this complex structuring of working hours and entitlement to pay was that the dockyards depended heavily on accurate timekeeping, more so than almost any other aspect of British life in the seventeenth century. Every dockyard had a clock, which was usually the most prominent feature in the yard; those at Chatham and Woolwich had been in place from at least the 1630s onwards.51 This was supplemented by a bell, which rang at the beginning and end of the day’s work, and the porter of the gate kept time for the yard with an hourglass, thus replicating the practice followed at sea.52

Inevitably, the strength of the dockyard workers’ position in such matters as employment, pay and perquisites depended heavily on the laws of supply and demand. At the beginning of a war, the naval administration was desperate to man the yards, and workers – especially the most skilled, such as the shipwrights – were in a very strong position. Peace brought an exact reversal and gave the upper hand to the administrators. Moreover, the traditional system for paying the yards, and the financial weakness of the administration for much of the period, militated against the men’s interests. Entitlement to pay was determined by regular musters of the yard by the clerk of the cheque, but his books were forwarded to London only once a quarter, so that wages were automatically at least three months in arrears. In practice, arrears often mounted well beyond this; some quarters of 1666 were not paid until 1671, and in 1683, during a period of particularly severe retrenchment, the yards were seven quarters in arrears. There was also considerable inconsistency in the administration’s treatment of the yards, which were not necessarily paid simultaneously or on the same basis. Workers therefore often had to live off their savings or on credit, and when those were exhausted the outcome could be quite literally fatal; in 1667 it was reported from Harwich that ‘several labourers and carpenters [were] dead for want of diet and nourishment’.53 The options available to the men for redress of these grievances were usually limited to such deferential forms of protest as petitioning.54 In 1659, for example, the shipwrights, ropemakers and caulkers petitioned for their pay, which they had not received for a year, and in 1673 the workmen of Portsmouth petitioned respectfully for five quarters’ pay.55 In extremis, though, the workforce could resort to direct action. Strikes over the lateness of pay were common throughout the 1660s and 1670s, and some of these revealed a sophisticated grasp of both labour relations and ‘news management. In 1670 the 250 men at Portsmouth went on strike, apparently to preempt an imminent cessation of work at the yard, and timed their walkout to ensure that news of it made the post to London.56

The clockhouse at Woolwich dockyard. Its replacement, built in the 1780s, still survives.

(BRITISH LIBRARY, KINGS MS 43)

Dockyard workers were jealously proud of their status and operated a byzantine system of restrictive practices, most of which were of very long standing. A man’s tools were his private property, not that of king or Commonwealth. The apprenticeship system, too, was sacrosanct, and breaches of it often led to direct action.57 But the apprenticeship system was also innately weak: there were too few apprentices to ensure a steady supply, and most of those who were taken on were indentured to the officers, rather than to skilled men.58 Ropemakers claimed that they were paid to produce only a certain amount each day, and if they completed their quota by dinner time (at about noon), they believed they were entitled to spend the rest of the day in the alehouse.59 The most common, and most controversial, perquisite was the practice of removing ‘chips’ from the dockyard, originally a means of keeping the yards clean of small pieces of left-over timber. By tradition, workers were allowed to remove these from the yard for their own purposes, from fuelling their own hearths to selling on the open market. The latter was a particularly valuable means of sustenance when their pay from the state was heavily in arrears, for income from chips could be the only means of keeping creditors at bay.60 The name implies small wood cuttings left over from the cutting of large pieces, but workers inevitably stretched the definition to its limit, as shown by the various rules that were brought in to restrict the practice, such as the prohibition of carrying ‘chips on the shoulder’.61 Like most similar injunctions about chips, this proved to be a dead letter, and in practice men were able to carry out of the yard pieces of wood that were up to three feet long. There was a strong suspicion that men spent much of their time deliberately cutting wood into pieces just under the maximum length, and this was reflected in the domestic architecture of the dockyard towns, where stairs, shutters and other domestic fittings were often slightly less than three feet wide.62

The amounts taken out of the yard were certainly not insignificant. During one experiment at Chatham, 400 shipwrights carried out their usual bundles of chips, which were then collected, weighed and found to be sufficient to fill a 30-ton ballast lighter. Moreover, the practice at Chatham was to carry chips away just once a day; men at Deptford claimed a right to carry chips out of their yard no fewer than three times each day, often carrying them directly to the many alehouses around the yard, where they exchanged them for drink (or so Pepys claimed).63 It was hardly surprising that critics of the system claimed that men were spending several hours a day doing nothing more than cutting chips for their own benefit, and in 1674 it was suggested that the system had been extended to include the manufacture of tables, desks, picture frames and even beehives for private use.64 Nevertheless, the practice of‘chips’ survived a number of halfhearted attempts to restrict or suppress it, primarily because the authorities ultimately had to prioritise the fire risk to the yards posed by large quantities of chips remaining in situ, and for all its problems, the workmen’s right to remove chips at least provided a quick and effective way of making the yards safe.65 The concerted attempt to suppress the practice in 1674–5 failed because the proposed alternative, a public sale of chips, attracted not one buyer, presumably as a result of a carefully co-ordinated boycott within the wider communities around the dockyards. In 1677 Charles II and the Admiralty finally admitted defeat, albeit not publicly; instead, they permitted ‘a silent connivance … to give way to the workmen’s falling to their ancient practice’.66 There were other failed attempts to suppress the practice of chips in 1634 and 1650, and several more during the eighteenth century; it was finally commuted into a cash payment only in 1801.67

There was clearly a very fine line between the marginally legitimate perquisite of‘chips’ and the wholly illegal practice of embezzlement. Few stretched the definition of a ‘chip’ quite as far as the three men of Chatham yard who made off with an entire ‘great mast’ in 166868, but yard officers and the Navy Board had to make regular injunctions against various shades of outright theft. Attempts were made to mark the state’s goods, often with the ubiquitous mark of a broad arrow, but it was impossible to do this to ironwork and some other commodities. The very regularity of the injunctions against embezzlement suggests the all-pervasiveness of the practice and the relative ineffectiveness of the attempts at control.69 It was also possible for members of the public simply to wander into the yards, and even onto the ships, especially on Sundays and holidays; not surprisingly, significant quantities of naval stores simply vanished, and in 1663 an entire storehouse full of pilfered naval stores, including iron shot, was discovered at Horsleydown (Southwark).70 Embezzlement from the yards naturally tended to increase as the pay due to the workforce slipped further into arrears.71 The endemic embezzlement from the yards led to attempts to improve security. All yards employed teams of watchmen, and these increased significantly in size during the period, particularly as a result of an order of 1669 that extended the watchmen’s duty hours, increasing their pay from 8d to one shilling a night in consequence. In 1660 Deptford had three watches of six men each. Four years later each watch comprised eight men, but by 1679 these had increased to twenty-two. At Portsmouth, the total number of watchmen increased from thirteen in 1660 to seventy-three in 1680.72

‘EFFICIENT’ DOCKYARDS?

Critics of the dockyards’ performance claimed to find ample evidence of their inadequacies, in particular the corruption of the officers and the idleness of the men. Pepys was one of the most trenchant critics of the workforce: in 1662 he described Deptford’s men as lazy and found Chatham full of‘old decrepid men’, while in 1684 he accused the workers in the yards of shoddy workmanship and ‘habitual sloth’.73 Such accusations, along with the elaborate ‘Spanish practices’ in force at the yards and a (wholly false) perception of greater efficiency in private yards and in the Netherlands, led some, both at the time and more recently, to conclude that the dockyards were shamefully inefficient.74 Ultimately, though, late twentieth-century criteria for measuring ‘efficiency’, drawn from flawed theories of management, have little value when assessing seventeenth-century dockyards on the only criterion that mattered, their effectiveness in meeting what was demanded of them. The men, systems and infrastructure that could take a fleet shattered in the Four Days’ Battle of 1–4 June 1666, the longest and most ferocious conflict in the entire age of sail, repair it, and send it back to sea to win a victory against the same opponents just seven weeks later, clearly did not constitute an ineffective organisation.75