The French Navy

DEVELOPMENT

FRANCE HAD A PROUD NAVAL TRADITION stretching back into the Middle Ages. Defeats, such as the battle of Sluys in 1340, were offset by successes, such as the campaign of 1545, when a large fleet had occupied the Solent (bringing on the action in which the Mary Rose was lost). But the size and effectiveness of the navy depended greatly on the personal inclinations of individual monarchs, and the long wars of religion (1562–98) inevitably caused much disruption. Cardinal Richelieu, chief minister from about 1624 to 1642, determined on the construction of a modern navy. He reformed the administration and recruitment system and constructed new bases, and in the year of his death the navy had in service sixty-three ships and twenty-eight galleys.1 This formidable force disintegrated within a few years of the cardinal’s demise. Another series of civil wars, the Frondes of 1648–53, lack of money and the lack of interest shown by Richelieu’s successor Cardinal Mazarin all contributed to a precipitate decline in the navy’s fortunes. By 1661, when the young King Louis XIV assumed control of the government in person, the fleet had been reduced to twenty ships (only one of which carried more than sixty guns) and six galleys, many of which were unserviceable, and the naval budget had declined from several million livres to only some 300,000. In the same year, though, Louis appointed a new intendant of finance, Jean-Baptiste Colbert. The new minister took a particular interest in the navy, seeing it as an essential means for France to increase her authority and her share of global trade; in 1663 Colbert became additionally intendant de la marine, and in 1669 secretary of state for the navy, a post giving him unprecedented control over French maritime policy. He used his authority to oversee the construction of an almost entirely new navy, and the scale of his achievement was remarkable.2 In 1671, only ten years after the disastrous nadir of the French navy, it possessed 119 ships, the largest of which carried 120 guns.3 Pepys was somewhat in awe of this astonishing phenomenon. He praised the sailing qualities of French ships, their recruitment and payment systems, their discipline, and credited them with all sorts of technical and other innovations.4 The enhanced office of secretary of the Admiralty, created for him in 1684, was modelled closely on Colbert’s. ‘Is there any one good rule in our navy that has not been long established in France?’ he once enquired, perhaps rather too credulously.5

ADMINISTRATION

The highly centralised nature of the French state, and the absence of obstreperous representative institutions (the Estates-General had not met since 1614), gave Colbert an unrivalled opportunity to implement his agenda. The traditional office of admiral of France had been suspended by Richelieu, who made himself surintendant de la marine, but when the nominal holder of this office died in 1669, Louis and Colbert revived the admiral’s position, albeit by giving it to a two-year-old royal bastard, the Comte de Vermandois. He was succeeded in 1683 by his five-year-old half-brother, the Comte de Toulouse, who in time became the last admiral of France to take his title seriously, commanding the fleet in the Gibraltar and Malaga campaign of 1704. At his death in 1683, Colbert was succeeded by his son Seignelay, who in turn was succeeded in 1690 by Pontchartrain, a financial administrator who cared little for the navy.

Jean-Baptiste Colbert, the man primarily responsible for the remarkable renaissance of the French navy in the 1660s.

(© TRUSTEES OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM)

BASES

Richelieu had established four naval bases at Toulon, Brest, Le Havre and Brouage, south of the Charente estuary. The last of these suffered from silting and was not brought back into use as a naval port, while Le Havre lacked a good roadstead and became confined largely to shipbuilding.6 The absence of a major dockyard in the English Channel would cause the French navy endless difficulties in the long wars with Britain after 1689, for even a temporary mastery of the Channel (such as that achieved after the battle of Beachy Head in 1690) could not be sustained. However, the extant French dockyards became models of their kind. Brest and Toulon were greatly expanded, the latter serving as the base for the galley fleet. An entirely new yard was built at Rochefort, on the Charente, which replaced Brouage. Selected for the role by Colbert in 1665, it included in its infrastructure a ropeyard, the corderie royale (which at the time of its completion in 1669 was the longest building in Europe), and a stone dry dock, the most advanced of its kind.7 A series of elaborate fortifications was designed by Marshal Vauban, who also upgraded the defences of the other yards. Dunkirk, another object of Vauban’s attentions, became a base for smaller ships and also became an important naval shipbuilding facility.8 Each dockyard was administered by an intendant, responsible directly to Colbert, and like their approximate equivalents in Britain, the resident commissioners, these clashed frequently with their workforces and with haughty aristocratic captains who resented civilian direction. Dedicated naval hospitals were set up at Brest, Rochefort and Toulon in 1667, predating the English equivalent at Greenwich by well over a quarter-century.9

The corderie royale at Rochefort.

(ANNE COATS)

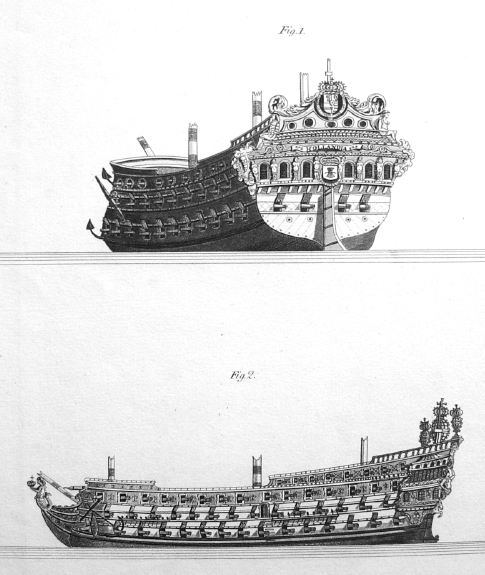

The Soleil Royal, built at Brest in 1669, was Tourville’s flagship at Beachy Head and Barfleur, but was destroyed by a British fireship shortly after the latter battle.

SHIPS

The imperative to create a state-of-the-art fleet virtually from scratch necessitated, in the early days, a wholesale reliance on foreign expertise. Several Dutch shipwrights went to work in France, and a number of warships were built in Dutch and Danish yards. Pepys’s friend Sir Anthony Deane went to France in 1675, although he built only two small yachts for the king’s personal use. A more substantial contribution was made by the Neapolitan Biagio Pangalo, or Maître Blaise, who gave French ships finer lines at the bow and stern, making them faster than many of their British or Dutch counterparts.10 More or less overt spying was also used: in 1670–1 Colbert’s son and eventual successor Seignelay was sent on intelligence-gathering visits to Venice, Amsterdam and London.11 The influx of all this expertise enabled Colbert to embark between 1668 and 1672 on a shipbuilding programme of astonishing scale and speed. Six three-deckers were launched at Toulon and Brest in 1668–9. The Royal-Louis was the largest ship in the world, but she and her sisters were essentially prestige symbols and did not prove particularly successful in service.12 Even so, La Reine was the flagship of d’Estrées at the battles of Schooneveld and the Texel in 1673, and Le Soleil Royal was Tourville’s flagship at Beachy Head and Barfleur. As well as establishing a new fleet of ships-of-the-line, the French continued to maintain a substantial galley fleet in the Mediterranean. This expanded almost as dramatically as the sailing navy, despite the considerable expense that fitting out a galley entailed; it reached a peak of fifty vessels in the 1690s, after which it began a long decline which ended in its abolition in 1748. As well as providing an instrument of sea power in the Mediterranean, the galleys served as a floating prison for deserters and criminals, who together formed about three-quarters of the crews, but also for political and religious dissidents, particularly the Protestant Huguenots.13

The French copied the British system of rating ships. First Rates carried from seventy-six to 110 guns, 36-pounders on the lower deck, 18-pounders above, and 8- or 12-pounders on the upper deck. Second Rates (most of which were two deckers) carried sixty-four to seventy-four guns, and Third Rates fifty to sixty, the largest on both rates being 24-pounders. Fourth Rates mounted forty to forty-six guns, Fifth Rates about thirty. Lesser ships were known as ‘frigates’.14 These French ships were usually bigger than British ships of the equivalent rate but tended to carry fewer guns, mounted higher in the hull.15 They were also more elaborately decorated, particularly those built at Toulon, where the sculptor Pierre Puget gave his imagination free rein and turned his ships into floating baroque extravaganzas.16 The expansion of the fleet was accompanied by greater focus on naval gunnery. A corps of naval gunners was established, calibres were standardised, and between 1661 and 1692 the numbers of 36-pounder cannon in the inventory increased from thirteen to 442, and of 18-pounders from 151 to 1,571.17

Anne-Hilarion de Cotentin, Comte de Tourville (1642-1701), the most successful French officer of the period.

OFFICERS

Louis and Colbert preferred to draw their commissioned officers from the ranks of the French nobility. François, Duc de Beaufort, who commanded the French fleet that threatened the English Channel in 1666, thereby creating the panic that led to the division of the British fleet, was a grandson of King Henri IV. Jean, Comte d’Estrées, who commanded the French fleet that combined with Britain’s in 1672–3, was the son of a duke and a Marshal of France and had served as a soldier in the 1640s and 1650s. Many officers, particularly those of the galley fleet, were Knights of the Order of Malta or had served in the order’s galleys; the most prominent of these was Anne-Hilarion de Cotentin, Comte de Tourville, who was commander-in-chief of the French fleet at the battles of Beachy Head (1690) and Barfleur (1692). Nevertheless, it was still possible for men of less exalted birth to gain important commands. Abraham Duquesne, who had distinguished himself in Richelieu’s navy, was of relatively humble origins in Rouen.18 The decline in the French navy’s fortunes meant that he was unemployed between 1650 and 1663, but he then held a succession of prominent commands, winning a stunning triumph over de Ruyter at Augusta in 1676. The privateer Jean Bart also carved out a successful naval career despite his humble origins. Several of the leading officers were Protestants, among them Duquesne and des Rabesnières, who commanded the rear division of the French squadron at the battle of Solebay in 1672. However, this became less common as the king’s stringent campaign against his Huguenot minority became more intense, culminating in the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes (1685), which drove many Protestants out of France, and those who remained often had to convert to keep their com-missions.19 One French officer, a lieutenant named Abel de Verdun, resumed his career in Charles II’s navy, where he was granted a midshipman extraordinary’s place in 1683.20

At first the French used two flag posts, chef-d’escadre and lieutenant-general, appointing six of the former and two of the latter, but the numbers of flagmen increased as the fleet expanded, and viceadmirals were appointed for both the Atlantic and the Mediterranean. When fighting alongside the British in 1672–3, the French squadron was commanded by the vice-admiral of the Atlantic (d’Estrées), with the two subordinate divisions commanded by chefs-d’escadre. At Barfleur in 1692 the fleet was again commanded by the vice-admiral (Tourville), but each subordinate squadron was commanded by a lieutenant-general, and all three squadrons had two chefs-d’escadre, giving a total of nine flag officers identical to the British pattern. Commissioned ranks were modelled essentially on the Dutch system, with lieutenants, frigate captains (capitaines de frigate, the equivalent of the British ‘master and commander’) and full captains (capitaines de vaisseau, the equivalent of post-captains). Colbert also introduced a corps of trainee officers, the Gardes de la Marine.21

SEAMEN

Richelieu had introduced a system of registering seamen, and Colbert built on this by introducing the Inscription Maritime. Between 1668 and 1670 a system of compulsory registration was enforced, and this became the bases of the ‘maritime classes, a rotation system in which those not immediately called up were paid a retaining fee. There were four classes in each of the largest Atlantic maritime provinces (Brittany, Normandy, Guyenne and Picardy) and three in smaller or Mediterranean provinces. Each class spent a year in the navy, the other years in the fishing or merchant fleets.22 Although there was some initial resistance, the system worked, at least in peacetime, partly because it provided free education for the children of those in service, and payment was made directly to men’s homes, unlike the frequently chaotic system employed in Britain. A Caisse des Invalides was established in 1673 to care for the wounded. In wartime, France had to resort to embargoes and other means of bolstering its recruitment, but at least the ‘maritime classes’ provided an initial draft of men quickly, and this often enabled it to get its fleet to sea before the British or the Dutch.23

The ‘vieïūe forme, the revolutionary dry dock at Rochefort, was built with stone sides in 1669-71; a stone bottom was added in 1683–8. This dock was the precursor of the stone dry docks built at Portsmouth and Plymouth in the 1690s.

(ANN COATS)

TACTICS

The experience of fighting in a combined Anglo-French fleet during the war with the Dutch (1672–4) led to the adoption of the line of battle by Colbert’s new navy. It took some time to adapt to the demands of this tactic, and the performance of the French in battle was severely criticised, but by 1675–6 French fleets were able to more than hold their own against the Dutch in the Mediterranean, and in 1690 Tourville inflicted a humiliating defeat on the British at Beachy Head. Tourville’s chaplain Paul Hoste, who served at both Beachy Head and Barfleur, subsequently wrote (at Tourville’s behest) the first detailed theoretical work on line tactics, L’artdes armées navales ou traité des evolutions navales (1697). The fact that French ships generally carried their guns higher than their British counterparts contributed to a tendency to shoot at an opponent’s masts and rigging rather than into the hull, but their often excellent sailing qualities and strong hulls enabled them to both escape and take punishment if necessary.

MERCHANT SHIPPING AND PRIVATEERS

At the beginning of the period, France’s merchant marine was tiny compared with those of its Western European rivals; in 1664 the country had only 283 ships of more than a hundred tons.24 The wine, brandy and salt trades of La Rochelle were controlled by the Dutch, although the amounts shipped were often impressive; throughout the seventeenth century, France supplied at least 20 per cent of the salt entering the Baltic. Bordeaux was heavily involved in the Newfoundland fisheries and traded extensively with England and the Netherlands, while Marseilles was the chief port for importing raw silk.25 The aggressive mercantilist and colonial policies of Colbert led to a transformation, with trade to the wealthy colonies in the Caribbean (and the consequent re-export trade to northern Europe) contributing most to a massive increase. Departures from Bordeaux by French-flagged ships more than doubled between 1651 and 1682, and by 1686 France had 671 ships of more than a hundred tons; between 1664 and 1704 the number based at Nantes alone increased from twelve to 151.26

France’s acquisition of Dunkirk in 1662 gave it a port that already had a long tradition as a nest of privateers. Dunkirk more than lived up to its reputation in the wars that followed, and the demolition of its fortifications became one of the terms that the British and Dutch most insisted upon in the drafting of the Treaty of Utrecht (1713).27 The most famous Dunkirk privateer of the period, Jean Bart, served under de Ruyter in the Dutch navy, captured over eighty prizes in the war against the Dutch from 1672 onwards, and eventually rose to high command in the navy. The other great centre of French privateering was St Malo in Brittany. As early as 1666 this set out the impressive privateer Notre Dame de Mountcarmel; although of just thirty-six tons and five guns, she carried sixty-six men armed with twenty muskets and thirty-six pistols, and was captured only after a ferocious fight in which the captain and five men were killed and another twenty-two mortally wounded.28 St Malo truly came into its own after the outbreak of war with Britain in 1689. The Malouin René Duguay-Trouin gained command of his first privateer in 1691, aged eighteen, and by the end of the war his exploits had earned him a command in the French navy; he eventually became lieutenant-general.