Fighting Tactics: The Evolution and Development of the Line of Battle

DURING THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY the warships of all northern powers were gradually fitted with increasing numbers of guns, and most of these came to be mounted along the sides of the ship. This was partly a response to the perceived superiority of the galley, which mounted a few heavy guns right forward, but for decades naval officers continued to favour the traditional tactic of attacking in line abreast, in relatively small groups of ships which could thus come easily to each other’s support. This remained the case even after the 1580s, when English ships began to adopt the practice of approaching the enemy in line ahead to maximise their firepower. This tactic involved a figure-of-eight or circle formation, in which individual ships came into action in turn against the enemy vessels that were closest to the wind, and was therefore certainly not a ‘line of battle’ in the later meaning of the term.1 To many, the ‘line’ is almost the epitome of the era of sailing warfare: two great fleets, each in a close-hauled line with each ship in the wake of its predecessor, slowly coming together until the lines are parallel, when a murderous bombardment begins. English warships were certainly capable of fighting in such a way from the late sixteenth century onwards, but it took several more decades for the logic of the new emphasis on broadside gunnery to make its mark on fleet tactics.

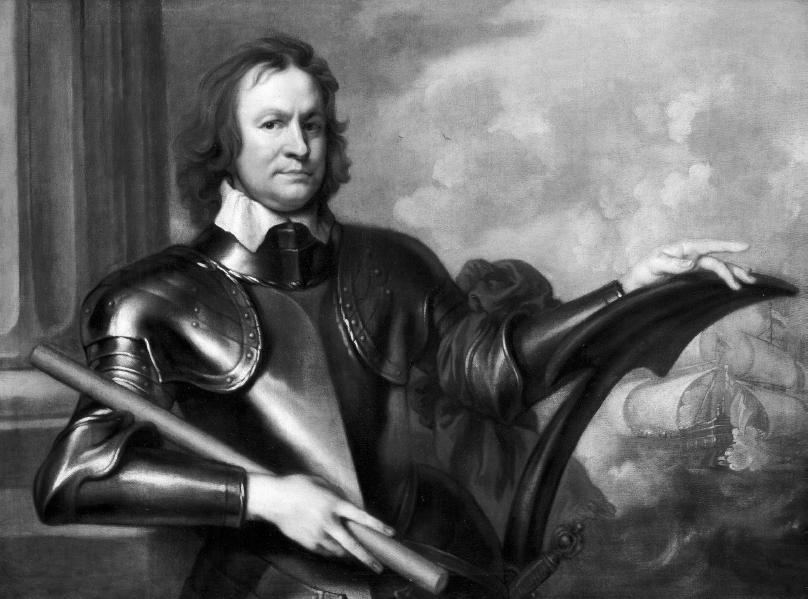

Richard Deane, general at sea. An artillery expert, Deane was killed at the Battle of the Gabbard in 1653.

(NATIONAL MARITIME MUSEUM, GREENWICH)

THE BEGINNING OF THE FIRST DUTCH WAR, THE ‘GENERALS-AT-SEA’ AND THE FIGHTING INSTRUCTIONS OF 1653

The outbreak of war with the Dutch in 1652 was the catalyst for important shifts in tactical thinking. For one thing, the fleets were vastly larger than those deployed in earlier wars; in the largest actions, over one hundred ships fought on each side, and with neither side contemplating invasion and the transport ships that such a strategy would entail, these all carried their main armaments along the broadside. For another, several major naval battles took place within an unprecedentedly short period of time, allowing the rapid evolution of tactical thinking based on experience. There were six large battles in the Channel and North Sea in one year, between the summers of 1652 and 1653 (there had been just two major fleet actions in the whole course of the Anglo-Spanish war of 1585–1604). Both sides were determined to seek each other out and fight, primarily because the stakes were so high (but also because they had little idea of what else to do). The Dutch were determined to run their merchant convoys through the English Channel; the British were equally determined to eliminate the Dutch fleet and destroy their maritime trade.

At first, the old tactics still held sway, with much talk in contemporary accounts of‘charging’-presumably passing through the enemy fleet from windward to leeward.2 But the British performance in the opening battles of the war was mixed, at best, and tactics on both sides were confused.3 A disastrous defeat at Dungeness in December 1652 was attributed in part to the failure of several captains, mostly those in command of armed merchantmen, to support each other and their general-at-sea, Blake. What could have been an even worse disaster off Portland in February 1653, when the isolated Blake was almost surrounded by Tromp’s Dutch fleet, was salvaged only by the heavier artillery on the British ships, which drove the Dutch back. The experience of these battles might have suggested both that a more effective command structure was needed, and that the advantage in weight of ordnance over the more lightly built and armed Dutch ships needed to be exploited to the full. In the immediate aftermath of Dungeness, a clearer system of three distinct squadrons was established, and naval captains were put in to command the armed merchantmen, replacing the masters put in by the owners. In the aftermath of Portland, the fleet’s tactics were re-thought. It has been suggested that one of the reasons for Blake’s ultimate success in that battle is that at the critical moment his fleet inadvertently formed a line, and that the impact of the bombardment it then delivered against the Dutch persuaded the generals-at-sea of the merits of that formation.4 This may be so (accounts of the battle are too confused to permit finality), but in any event, the experience of the battles up to and including Portland clearly influenced what happened next.

On 29 March 1653 the generals-at-sea issued a new set of twenty-one sailing instructions, along with fourteen ‘Instructions for the Better Ordering of the Fleet in Fighting’. These specified that ‘all ships of every squadron shall endeavour to keep in a line with the chief’, with the vice-admiral on the admiral’s ‘right wing’ and the rear-admiral on the left. Much emphasis was placed on the need for ships to support each other.5 The wording of the instructions is not entirely clear, as they covered only the approach to the enemy and not the engagement itself; much emphasis was placed on the need for ships to stay close to each other to give mutual support. Nevertheless, the third article implied that the line would be maintained throughout the action, and in practice there would have been little reason to abandon a formation which would bring the maximum weight of shot to bear at the moment of contact with the enemy.6 The greater emphasis on broadside gunnery was almost certainly a consequence of the appointment of generals-at-sea, army officers who would have been familiar with the merits of bombardment and who sought to impose military methods on the navy. This is certainly evident in the 1653 fighting instructions, with their talk of‘wings’ and generally military language. Attempts have been made to ascribe the introduction of line tactics to one individual, and plausible cases have been made for both Blake and Monck.7 It may be significant that no change in tactics was made after the first three battles of the war, but only after the fourth, when both Monck and Deane had joined the fleet and seen its strengths and weaknesses at first hand. Of all the generals-at-sea, Deane had by far the most impressive credentials as an artillery specialist, but he has also attracted less attention from biographers, and his death in the first battle after the adoption of the fighting instructions may have led to an unjust neglect of his con-tribution.8 On the other hand, it would have been impossible for one general to impose a radically new tactical idea on the other two (especially when such powerful personalities as Blake and Monck were involved, even though Blake was ill at the time). Moreover, they would hardly have made such an important innovation if its feasibility had not been accepted by the senior professional seamen present in the council of war, notably William Penn, another candidate favoured by some as the originator of‘line tactics’, albeit chiefly by reading backwards from Penn’s strong advocacy of the line some ten years later.9 The new instructions must have been the product of a consensus, born of recent experience and of the three generals’ innate grasp of military‘first principles’.

THE LATER BATTLES OF THE FIRST ANGLO-DUTCH WAR

The accounts of the last two battles of the war, the Gabbard on 2–3 June and Scheveningen on 31 July 1653, are particularly unclear. The Gabbard was fought in light winds, but on the first day the British seem to have formed a line about 500 yards from the Dutch ships and proceeded to bombard them for several hours. Monck seems to have reverted to more traditional tactics on the second day of the battle, apparently approaching in three squadrons in line abreast and then resorting to melee tactics (perhaps an unwitting comment on the removal of Deane’s influence, for he had been killed early on the first day). At Scheveningen, Monck seems to have held his line together for four passes, smashing through the Dutch fleet each time and inflicting devastating casualties, though this can also be interpreted as a reversion to the older tactic of‘charging’ from windward to leeward.10 The lesson to be drawn from the two battles could hardly have been clearer. In the four preceding battles, the British had sunk or captured perhaps sixteen Dutch ships, at a cost of five of their own. In the final two battles, some twenty-three Dutch ships were lost, at a cost to the victors of only two.11 Tromp was killed at Scheveningen, and, taken together, the two battles saw several thousands of his fellow countrymen lose their lives or freedom. The Dutch had not adopted line tactics, and their comparatively small ships proved desperately vulnerable to the broadside fire of their opponents.

COMMAND AND CONTROL: THE DEVELOPMENT OF SIGNALLING

Although the line of battle may have been introduced partly with a view to improving an admiral’s control over his fleet, in practice it made it such control much more difficult to achieve. In earlier (and much smaller) fleets which fought in groups, and perhaps in line abreast also, the admiral could usually see or be seen, and orders could probably be transmitted fairly easily by boat or by hailing.12 But the fleets of over one hundred vessels that served during the Anglo-Dutch wars would be stretched out over at least seven or eight miles of ocean, often much more, and in practice it was impossible for the admiral, usually at the very centre, to communicate directly with, or even to see, the ships at the ends of his line.13 Once battle was joined, gunsmoke would exacerbate the problem. Admirals could seek to overcome the new problem of control in one of two ways, though these were not mutually exclusive.14

Firstly, their subordinates could be thoroughly schooled in tactical doctrine, so that if a given situation arose they would automatically respond in a predetermined way. This was very much the intention of the increasingly lengthy and elaborate sets of fighting instructions that were issued during the Anglo-Dutch wars and then from 1689 through into the eighteenth century. Secondly, the admiral could seek to communicate his intentions by using signals. The 1653 instructions mention only a handful of flag signals: a red flag at the admiral’s foretopmast head (the ‘bloody flag’) was the signal to engage, a blue flag at the mizzen yard or topmast was the signal to bear up into the admiral’s wake and grain (both astern and ahead) if the fleet was to windward of the enemy, while pennants signified that ships should come up to the relief of a squadron in difficulties. It was assumed that all ships would be able to see the admiral’s signal, but no provision was made by which they could signify whether or not they had.15 A rudimentary system of repeating was mentioned in only one instruction, for ships to attempt to gain the wind of an enemy, when the admiral would put a red flag at his spritsail, topmast shrouds, forestay or main topmast stay, and the first ship to spot it would hoist and lower his sail or ensign as a signal to others; even so, Van de Velde pictures of some of the battles of the time show that subordinate flag officers did repeat their admirals’ signals to their own divisions.16 Lowering or loosing the sails, and firing some guns, was one of the few methods of conveying urgency, for instance when an enemy fleet was sighted. Thus the Tiger signalled the presence of the Dutch fleet off Harwich on 1 July 1666 by firing two guns in the afternoon, followed by four guns a few hours later, and the signal of four guns in the evening was then repeated by other ships as long as the enemy were in sight.17

The instructions issued by the Earl of Sandwich and the Duke of York in 1665 added several new flag signals to cover various eventualities. The most important of the new instructions introduced the notion of the close-hauled line (that is, sailing close to the wind), in which the ships would be half a cable’s length apart, and a signal of a Union flag at the foretopmast head to order the fleet to tack in succession from the van, and of the Union at the mizzen topmast head to order it to do so from the rear.18 Further instructions were added by the Duke of York in 1672–3, this time bound up with sailing and other instructions into one formal, standardised book, which became the pattern for subsequent tomes.19 Both the 1666 and 1672 sailing instructions included individual flag signals for the ships in each division; thus in 1672 the Mary Rose, the rearmost ship in the admiral of the Blue’s division, was allocated number ten, and her signal was a blue flag and pendant flown downwards from the backstays at the maintopmast head (the signal for her division) plus a pendant at the mizzen topmast shrouds for the individual ship.20 York’s instructions of 1672–3 also included template diagrams for each squadron, with blanks in which the names of individual ships could be inserted to show their place in the sailing order or the line of battle.21 But such increasingly elaborate paper attempts to coordinate the actions of individual ships begged the question of their efficacy in battle, and ultimately admirals had to rely on the common sense of their subordinates: the Earl of Ossory’s verbal commands to his division in 1673 were ‘in time of fight to keep in their line of battle and assist each other, and act like good men’.22

THE SECOND AND THIRD ANGLO-DUTCH WARS

The battle of Lowestoft in 1665 was the last action in which the British gained an overwhelming advantage from the line. The Dutch subsequently became much stronger, building larger ships with greater armament, and from the 1666 campaign onwards they, too, adopted the line of battle as their tactic of choice, abandoning their traditional tactic of close support and boarding and at once nullifying the advantage that the unilateral adoption of the line had given their enemies.23 It took them a little while to master line tactics: at the St James’s Day fight in 1666, their line swiftly became a half-moon to defend against fireship attacks, but one observer thought that the Dutch van or rear ought to have tacked to weather much of the British fleet (which had the wind).24 Generally, though, the Dutch were less enthusiastic to give battle than they had been in the first war, and usually sought to do so only when they had a significant tactical advantage or when they could fight defensively, close to their own shore. (The six full-scale fleet actions of the first war were followed by only three in the second and four in the third.) Two battles, the Four Days’ Battle of 1666 and Solebay in 1672, were effectively hasty responses to the arrival of the Dutch in British coastal waters, while the whole of the third war was fought in conjunction with a French squadron, whose competence (and willingness) to fight effectively in line was in doubt from the very beginning.

Moreover, the deficiencies of the signalling system caused serious difficulties. At Lowestoft in 1665 the use of the new signal for the fleet to tack from the rear initially caused considerable confusion (though it was brilliantly executed at the second attempt), while at the Texel in 1673 the loss of the admiral of the Blue, and thus of his controlling flag, and the failure of the French admiral (commanding the White squadron) to see or act upon the commander-in-chief’s signal, effectively stymied the two of the three squadrons of the Anglo-French fleet. The dependence of the entire tactical system on the ability of the admiral to make signals was also exposed at Solebay, where the flagship Royal Prince was careening at the moment of the Dutch attack and seems to have been unable to make any signal beyond the general one for the fleet to weigh.25 In any case, the very nature of the line, especially after the Dutch adopted the same tactic, tended to encourage a rapid degeneration into at least three distinct battles between different squadrons, which in turn often broke up into discrete fights between individual divisions. Consequently, the outcomes of individual battles, and of the wars as a whole, were markedly disappointing when compared with the halcyon days of the summer of 1653.

Nevertheless, several important refinements were made to line tactics during the Restoration period, and the fighting instructions were modified from time to time to take account of the experience of the preceding engagements.26 From 1665 onwards the lines were drawn up in advance, so that each ship knew her exact place in the order, and the organisation into three squadrons of three divisions each was made clearer.27 During the third war (though not during the second) the squadrons were organised so as to provide powerful ‘seconds’, usually immediately astern of the flagship of each squadron; both sides tended to target each other’s flags, which usually took the heaviest casualties during any engagement, and it was clearly sensible to give them as much protection as possible. Armed merchantmen were phased out of the line; they were less common in the second war than in the first, and had virtually disappeared by the third. Instead, it became increasingly common to place a large ship at the head and rear of each squadron’s line, and the flagships of divisions came to be placed in the centre, rather than in the van or rear (which was still the case in 1665).28 One or two Fifth Rate frigates and at least one fireship were stationed to windward of each flagship (this disposition, directed primarily against fireship attack, had been the subject of a formal fighting instruction since 165329), and the Red squadron, the commander-in-chief’s own, was always allocated the most powerful ships.30

The precise tactics to be followed were also made more explicit. For instance, York’s instructions of April 1665 specified that if attacking from windward, the leading squadron was to steer for the enemy’s van, if from leeward that ‘commanders … shall endeavour to put themselves in one line close upon the wind’. Captains were enjoined not to break away from the line to pursue individual enemy ships, an instruction that in later years became something of an excuse for caution and lack of individual initiative, but in the 1660s it was an entirely logical element of the new desire not to dissipate the awesome destructive potential of the line’s broadsides.31 On 18 July 1666 Prince Rupert and the Duke of Albemarle, joint commanders of the fleet, issued new instructions which included important innovations. The first instruction specified that a fleet holding the weather gauge was to keep the enemy to leeward at all costs, tacking if necessary to stay on the same tack as the enemy. This would eliminate the old method of continuous passing, but as ‘the only positive, as well as mandatory, fighting instruction actually specifying to the admiral how to fight the battle’ it would develop over the succeeding decades into one of the most significant tactical constraints on an admiral’s freedom of action.32 The second instruction provided a tactical blueprint if the enemy had the wind: the van was to attempt to break through the enemy’s line, then tack to come up to windward of the enemy’s van, while the centre squadron came up on the original tack, thereby doubling the enemy’s van.33

THE EXPERIENCE OF BATTLE

Casualty rates in the great battles of the Dutch wars were often hideous. During the Four Days’ Battle of 1666, the British lost over 1,000 killed; another 1,450 were wounded, and 1,800 made prisoners.34 At Solebay in 1672, 722 men were certainly killed and another 610 wounded.35 These figures do not include the wounded on several large ships, and also omit six ships entirely, including the greatest British casualty, the First Rate Royal James, which was burned by a Dutch fireship. Her flag captain reckoned that between 250 and 300 of her men were killed or wounded in the early stages of the battle alone,36 which would suggest that the total death toll in the fleet as a whole was about 1,000. However, losses were disproportionate; ships in the rear of squadrons or divisions often had very few casualties, while those at the heads and the flagships frequently had shocking attrition rates. At Solebay, for instance, the flagship Prince had ninety-five killed and wounded, while the Third Rate Fairfax, two ships ahead of her, had seventy-two; but the Second Rate French Ruby, at the rear of the rear-admiral of the Blue’s division, had only three killed and four wounded.37 The ships that bore the brunt became little more than floating abattoirs. Cannonballs and chain shot took off limbs and heads; huge shards of wood, deceptively known as ‘splinters’, broke away from hulls and decks as round shot struck, impaling themselves in any man who stood in their way. The Dutch prizes brought into Dover in 1653 were described by an eyewitness as ‘much dyed with blood, their masts and tackle being moiled with brains, hair, pieces of skulls …’.38 The greatest were not immune from such carnage. General-at-Sea Richard Deane was effectively cut in half by a cannonball, while the three aristocrats who stood alongside the Duke of York on the quarterdeck of his flagship during the battle of Lowestoft were killed by a single chain shot which decapitated the first man it reached, splattering the heir to the throne with blood and brains. With both sides targeting each other’s quarterdecks, losses among commissioned officers were always disproportionately high; at the Four Days’ Battle, two admirals and ten captains were killed, eight captains and another three admirals (including the Duke of Albemarle) were wounded, and one admiral and four captains, including two of the wounded ones, were captured.39

The St James’s Day fight. A somewhat idealised view from a contemporary broadside, which nevertheless illustrates the fact that the Dutch had adopted line tactics.

(© TRUSTEES OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM)

The effect of the Dutch tactic of firing high; a contemporary drawing of an un-named engagement between British and Dutch ships.

(© TRUSTEES OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM)

Single ship actions were often particularly vicious. On 3 August 1666 Captain Christopher Gunman’s Orange took on a big Dutch privateer. Gunman lost his left hand, taken off by a ‘great shot’; the Orange took 200 shot in her sails and seven more in her hull, lost her maintopmast, and ‘had not a whole rope in the ship, neither standing nor running’.40 When the Kingfisher went into battle against seven Algerine corsairs in 1681, Captain Morgan Kempthorne asked the chaplain to say a prayer, and in the early stages his efforts seemed to have been rewarded, for no-one was killed on the gundeck, despite successive broadsides and a hail of small shot from each of the corsair ships in turn. But then a great shot penetrated the side and killed and wounded several men in the gunroom. Casualties also mounted steadily on the quarterdeck, where Kempthorne was shot first in the hand, then had ‘part of his belly taken away with a cannon bullet, which killed him. Nevertheless, the lieutenant fought the ship out of her predicament, and got her safe to Naples.41

Officers paced the decks to encourage the men to fight; at the battle of Solebay in 1672 even the Duke of York, heir to the throne and Lord High Admiral, did this, which prompted his acting flag captain aboard the Prince to comment that the duke’s bravery was ‘most pleasant when the great shot are thundering about our ears’. The fact that the Dutch cannonballs were ‘about [the] ears’ of those on the quarterdeck, rather than striking the hull, testifies to the Dutch practice of firing into the rigging because they wished to disable ships prior to boarding.42 The Prince lost her maintopmast at Solebay, cut ‘clear asunder’ by one shot. The mast crashed onto the upper deck and brought down the mainsail, rendering the guns on that deck unworkable and the ship itself unmanageable.43 The guns of the upper deck were also incapacitated aboard the Royal James in the same battle, and the Dutch took advantage by peppering the deck with musket shot from their tops, wounding her flag captain in the foot.44 The Antelope ended the Four Days’ Battle with ‘the starboard side full of holes like a sieve, on the larboard a breech that a coach might enter, twelve of our guns broken, every mast, yard, and rope, with two suits of sails spoiled, the platform full of wounded or dismembered men …’.45

The first battle of Schooneveld, 28 May 1673. This drawing by Van de Velde the Elder, who was present, gives a vivid impression of the confusion that reigned in many battles, even after the introduction of the line.

(NATIONAL MARITIME MUSEUM, GREENWICH)

Some reacted coolly in the midst of such havoc. Frescheville Holles, captain of the Antelope, calmly toasted his crew with wine before going into battle; a few hours later, his arm was shot off.46 Thomas Browne, lieutenant of the Mary Rose in 1666–7, was a particularly well-educated officer who delighted in explaining the realities of naval life to his father, the eminent physician and author Sir Thomas Browne. The younger Browne was excited by the prospect of battle, but found that it made him thirsty, so he always took care to keep some bottles of beer by him as he fought. He thanked his father for his suggested method of preserving his ears in battle, but assured him the gunfire was not as intolerable as landsmen assumed. In the intervals between action, Browne turned to his books and his violin.47 Not all were so brave under fire. During the early battles of the Anglo-Dutch war, many captains (particularly those of hired merchantmen) simply refused to fight, and accusations of cowardice or of failing to support colleagues occurred in every battle of the age, leading to some vicious feuds between individual sea-officers.48 The nature of the battles meant that it was very difficult accurately to assess the behaviour of individual ships and men, and very easy for those who wished to do so to create plausible excuses for their failings. In 1673 Prince Rupert ordered captains to place a man in their ships’ poops to observe and assess critically the conduct of the other ships around them,49 but this was easier said then done. Battles were characterised by ‘the noise, the smoke, the fire, the blood … the flames of burning ships [and] the fiery flashes from the guns’. Smoke often made it impossible to see what was happening even at quite close quarters, especially in actions fought in light winds.50 This confusion also meant that ships on the same side sometimes fired into or over each other by mistake, and in 1666 captains were enjoined not to do so on pain of death.51