During the Archaic Age the Greeks fully developed the most widespread and influential of their new political forms, the city-state (polis). The term archaic, meaning “old-fashioned” and designating Greek history from approximately 750 to 500 B.C., stems from art history. Scholars of Greek art, employing criteria about what is beautiful, which today are no longer seen as absolute, judged the style of works from this period as looking more old-fashioned than the more-naturalistic art of the fifth and fourth centuries B.C. Art historians judged the sculpture and architecture from the following time period as setting what they saw as the classic standard of beauty and therefore named it the Classical Age. They thought that Archaic Age sculptors, for example, who created freestanding figures that stood stiffly, staring straight ahead in imitation of Egyptian statuary, were less developed than the artists of the Classical Age, who depicted their subjects in more-varied and active poses.

The question of the merits of its statues aside, the Archaic Age saw the gradual culmination of developments in social and political organization in ancient Greece that had begun much earlier in the Dark Age and that led to the emergence of the Greek city-state. Organized on the principle of citizenship, the city-state included in its population free male citizens, free female citizens, and their children, alongside noncitizen but free resident foreigners and nonfree slaves. Individuals and the community as a state both owned slaves. The Greek citystate was thus a complex community made up of people of very different legal and social statuses. Certainly one of its most remarkable characteristics was the extension of citizenship and a certain share of political rights to even the poorest freeborn local members of the community. Explaining how this remarkable development happened remains a central challenge for historians. Since these principles are taken for granted in many contemporary democracies, it can be easy to overlook how unusual—and frankly astonishing—they were in antiquity. Although poverty could make the lives of poor citizens as physically deprived as those of slaves, their having the status of citizen was a distinction that gave an extra meaning to the personal freedom that set them apart from the enslaved inhabitants of the city-state and the foreign residents there. In my judgment, the importance of citizenship in the city-state ranks as a wonder of the history of ancient Greece.

c. 800 B.C.: Greek trading contacts with Al Mina in Syria.

c. 775 B.C.: Euboeans found trading post on the island of Ischia in the Bay of Naples.

Before 750 B.C.: Phoenicians found colonies in western Mediterranean, such as at Cadiz (in modern Spain).

c. 750–700 B.C.: Oracle of Apollo at Delphi already famous.

c. 750–500 B.C.: The Greek Archaic Age.

c. 750 B.C.: Greek city-states beginning to organize spatially, socially, and religiously.

c. 750–550 B.C.: Greek colonies founded all around the Mediterranean region.

c. 700–650 B.C.: Hoplite armor for infantry becoming much more common in Greece.

c. 600 and after: Chattel slavery becomes increasingly common in Greece.

Polis, the Greek term from which we take the modern term politics, is usually translated as “city-state” to emphasize its difference from what we today normally think of as a city. As in many earlier states in the ancient Near East, the polis, territorially speaking, included not just an urban center, often protected by stout walls, but also countryside for some miles around, inhabited by residents living in villages from large to small. Members of a polis, then, could live in the town at its center and also in communities or single farmhouses scattered throughout its rural territory. In Greece, these people made up a community of citizens embodying a political state, and it was this partnership among citizens that represented the distinctive political characteristic of the polis. Only men had the right to political participation, but women still counted as members of the community legally, socially, and religiously.

The members of a polis constituted a religious association obliged to honor the state’s patron god as well as the other gods of Greece’s polytheistic religion. Each polis identified a particular god as its special protector, for example, Athena at Athens. Different communities could choose the same deity as their protector: Sparta, Athens’s chief rival in the Classical period, also had Athena as its patron divinity. The community expressed official obedience and respect to the gods through cults, which were regular systems of religious sacrifices, rituals, and festivals paid for by public funds and overseen by citizens serving as priests and priestesses. The central activity in a city-state’s cult was the sacrifice of animals to demonstrate to the gods as divine protectors the respect and piety of the members of the polis and to celebrate communal solidarity by sharing the roasted meat.

A polis had political unity among its urban and rural settlements of citizens and was independent as a state. Scholars disagree about the deepest origins of the Greek polis as a community whose members self-consciously assumed a common and shared political identity. Since by the Archaic Age the peoples of Greece had absorbed many innovations in technology, religious thought, and literature from other peoples throughout the eastern Mediterranean region and the Near East, it has been suggested that Greeks might have been influenced also by earlier political developments elsewhere, for example, as in the city-kingdoms on Cyprus or the cities of Phoenicia. It is difficult to imagine, however, how political, as opposed to cultural, precedents might have been transmitted to Greece from the East. The stream of Near Eastern traders, crafts specialists, and travelers to Greece in the Dark Age could more easily bring technological, religious, and artistic ideas with them than political systems. One Dark Age condition that certainly did affect the formation of the city-state was the absence of powerful imperial states in Greece. The political extinction of Mycenaean civilization had left a vacuum of power that made it possible for small, independent city-states to emerge without being overwhelmed by large states.

What matters most is that the Greek city-state was organized politically on the concept of citizenship for all its indigenous free inhabitants. This concept did not come from the Near East, where rulers ruled subjects; prudent rulers took advice from their subjects and delegated responsibilities to them in the state, but their people were not citizens in the Greek sense. The distinctiveness of citizenship as the organizing principle for the reinvention of politics in this period in Greece was that it assumed in theory certain basic levels of legal equality, especially the expectation of equal treatment under the law and the right to speak one’s mind freely on political matters, with the exception that different regulations could apply to women in certain areas of life, such as acceptable sexual behavior and the control of property. The general legal (though not social) equality that the Greek city-state provided was not dependent on a citizen’s wealth. Since pronounced social differentiation between rich and poor had characterized the history of the ancient Near East and Greece of the Mycenaean Age and had once again become common in Greece by the late Dark Age, it is remarkable that a notion of some sort of legal equality, no matter how incomplete it may have been in practice, came to serve as the basis for the reorganization of Greek society in the Archaic Age. The polis based on citizenship remained the preeminent form of political and social organization in Greece from its earliest definite appearance about 750 B.C., when public sanctuaries serving a community were first attested archaeologically, until the beginning of the Roman Empire eight centuries later. The other most common new form of political organization in Greece was the “league” or “federation” (ethnos), a flexible form of association over a broad territory that was itself sometimes composed of city-states.

The most famous ancient analyst of Greek politics and society, the fourth-century B.C. philosopher Aristotle, insisted that the emergence of the polis had been the inevitable result of the forces of nature at work. “Humans,” he said, “are beings who by nature live in a polis” (Politics 1253a2–3). Anyone who existed self-sufficiently outside the community of a polis, Aristotle only half-jokingly maintained, must be either a beast or a god (Politics 1253a29). In referring to nature, Aristotle meant the combined effect of social and economic forces. But the geography of Greece also influenced the process by which this novel way of organizing human communities came about. The severely mountainous terrain of the mainland meant that city-states were often physically separated by significant barriers to easy communication, thus reinforcing their tendency to develop politically in isolation and not to cooperate with one another despite their common language and gods, the main components of the identity that Greeks in different places believed they all shared.

City-states could also exist next to one another with no great impediments to travel between them, as in the plains of Boeotia. A single Greek island could be home to multiple city-states maintaining their independence from one another: The large island of Lesbos in the eastern Aegean Sea was home to five different city-states. Since few city-states controlled enough arable land to grow food sufficient to feed a large body of citizens, polis communities no larger than several hundred to a couple of thousand people were normal even after the population of Greece rose dramatically at the end of the Dark Age. By the fifth century B.C., Athens had grown to perhaps forty thousand adult male citizens and a total population, including slaves and other noncitizens, of several hundred thousand people, but this was a rare exception to the generally small size of Greek city-states. A population as large as that of Classical Athens at its height could be supported only by the regular importation of food from abroad, which had to be financed by trade and other revenues.

Some Greeks had emigrated from the mainland eastward across the Aegean Sea to settle in Ionia (the western coast of Anatolia and islands close offshore) as early as the ninth century B.C. Starting around 750 B.C., however, Greeks began to settle even farther outside the Greek homeland. Within two hundred years of this date, Greeks had established “colonies” in areas that are today southern France, Spain, Sicily, southern Italy, and along North Africa and the coast of the Black Sea. It is important to remember that the contemporary word colonization implies “colonialism,” meaning the imposition of political and social control by an imperial power on subject populations. Early Greek “colonization” was not the result of imperialism in the modern sense, as there were no empires in Greece in this period. Greek colonies were founded by private entrepreneurs seeking new commercial opportunities for trade and by city-states hoping to solve social problems or improve their economic influence incrementally by establishing new communities of citizens in foreign locations.

Eventually the Greek world included hundreds of newly founded trading settlements and emerging city-states. The desire to own farmland and the revival of international trade in the Mediterranean in the Archaic Age probably provided the most important incentives for Greeks to leave their homeland. That is, the drive to improve one’s life financially was most likely the first and most powerful inducement motivating Greeks to make the difficult choice to emigrate, despite the clear and serious dangers in relocating to unfamiliar and often-hostile places. In any case, greater numbers of Greeks began to move abroad permanently beginning in the mid-eighth century B.C. By this date, the population explosion in the late Dark Age had caused a scarcity of land available for farming, the most desirable form of wealth in Greek culture. The disruptions and depopulation of the Dark Age originally had left much good land unoccupied, and families could send their offspring out to take possession of unclaimed fields. Eventually, however, this supply of free land was exhausted, producing tensions in some city-states through competition for land to farm. Emigration helped solve this problem by sending men without land to foreign regions, where they could acquire their own fields in the territory of colonies founded as new city-states.

Aiming to make one’s fortune in international commerce was clearly a motivation for many Greeks to leave the security of home behind. Some Greeks with commercial interests took up residence in foreign settlements, such as those founded in Spain in this period by the Phoenicians from Palestine. The Phoenicians were active in building commercially motivated settlements throughout the western Mediterranean, usually at spots where they could most easily trade for metals. For example, within a century of its foundation sometime before 750 B.C., the Phoenician settlement on the site of modern Cadiz in Spain had become a city thriving on economic and cultural interaction with the indigenous Iberian population. The natural resources of Spain included rich veins of metals.

Greeks also founded numerous trading posts abroad on their own as private enterprises. Traders from the island of Euboea, for instance, had already established commercial contacts by 800 B.C., with a community located on the Syrian coast at a site now called Al Mina. Men wealthy enough to finance risky expeditions by sea ranged far from home in search of metals. Homeric poetry testifies to the basic strategy of this entrepreneurial commodity trading. In The Odyssey, the goddess Athena once appears disguised as a metal trader to hide her identity from the son of the poem’s hero: “I am here at present,” she says to him, “with my ship and crew on our way across the wine-dark sea to foreign lands in search of copper; I am carrying iron now” (1, lines 178–188). By about 775, Euboeans, who seem to have been particularly active explorers, had also established a settlement for purposes of trade on the island of Ischia, in the Bay of Naples off southern Italy. There they processed iron ore imported from the Etruscans, a thriving population inhabiting central Italy. Archaeologists have documented the expanding overseas communication of the eighth century by finding Greek pottery at more than eighty sites outside the Greek homeland; by contrast, almost no pots have been found that were carried abroad in the tenth century. Patterns of trade in the Archaic Age reveal interdependent markets for which highly mobile merchants were focused on satisfying demand by supplying goods of all kinds, from raw materials to luxury items.

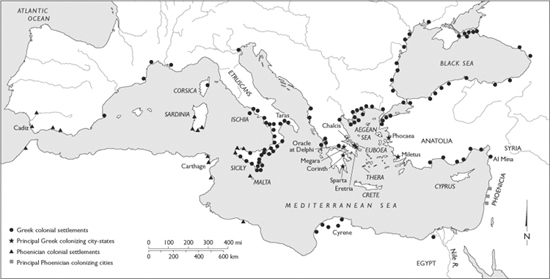

Map 3. Phoenician and Greek Colonization, c. 800–c. 500 B.C.

Hearing from overseas traders about places in which to relocate in search of a better life, Greek colonists sometimes went abroad as members of a group organized by their “mother city” (mētropolis), which would designate a group leader called the “founder” (ktistēs). Even though they were going to establish an independent city-state at their new location, colonists who left home on these publicly arranged expeditions were expected to retain ties with their metropolis. A colony that sided with its metropolis’s enemy in a war, for example, was regarded as disloyal. Sometimes colonists, whether private merchants setting up a trading spot on their own initiative or a group sent out by a mother city, enjoyed a friendly welcome from the local inhabitants where they settled; sometimes they had to fight to win land and a harbor for their new community. Since colonizing expeditions seem to have been usually all male, wives for the colonists had to be found among the locals, either through peaceful negotiation or by violent kidnappings. A colony with a founder expected him to lay out the settlement properly and parcel out the land, as Homer describes in speaking of the foundation of a fictional colony: “So [the founder] led them away, settling them in [a place called] Scheria, far from the bustle of men. He had a wall constructed around the town center, built houses, erected temples for the gods, and divided the land” (Odyssey 6, lines 7–10).

The foundation of Cyrene (in what is now Libya in North Africa) in about 630 B.C. reveals how contentious the process of colonization could be in some circumstances. The people of the polis of Thera, on an island north of Crete, apparently were unable to support their population. Sending out colonists therefore made sense as a solution to population pressures. A much later inscription (put up in the fourth century B.C.) found at Cyrene claims to record how the expedition was organized under the leadership of the founder Battus, as this excerpt from the longer text shows:

Since [the god] Apollo of Delphi spontaneously instructed Battus and the Therans to send a colony to Cyrene, the Therans decided to send Battus to North Africa as leader and king and for the Therans to sail as his companions. They are to go on the expedition on equal and fair terms according to their household and one adult son [from each family] is to be conscripted [and those who are to be chosen are to be those who are the adults, and of the other Therans only those who are free men are to sail]. And if the colonists succeed in establishing the settlement, men who sail to North Africa later on to join it shall share in citizenship and magistracies and shall be given portions from the land that no one owns. But if they fail to establish the settlement and the Therans are unable to send assistance and the colonists suffer hardship for five years, they shall depart from the land to Thera without fear of punishment, they can return to their own property, and they shall be citizens. And if any man is unwilling to depart for the colony once the polis decides to send him, he shall be liable to the death penalty and his property shall be confiscated. Any man who shelters or hides such a one, whether he is a father helping his son, or a brother aiding his brother, is to suffer the same penalty as the man who refuses to sail. An agreement was sworn on these conditions by those who remained in Thera and those who sailed to found the colony in Cyrene, and they invoked curses against those who break the agreement or fail to keep it, whether they were those who settled in North Africa or those who stayed behind.

—(Crawford and Whitehead, Archaic and Classical Greece, no. 16 = GHI, no. 5)

If this retrospective inscription accurately reports the original circumstances of the expedition—and some scholars think that it was an imaginary reconstruction of the original oath—then the young men of Thera were reluctant to leave their home for the new colony. Regardless of whether this particular text is reliable in its detail, it seems undeniable that Greek colonization was not always a matter of individual choice and initiative. The possibility of acquiring land in a colony on which a man could perhaps grow wealthy had to be weighed carefully against the terrors of being torn from family and friends to voyage over treacherous seas to regions posing a level of risk to the immigrants that was hard to calculate but never small. Greek colonists always had good reasons to be anxious about their future.

In some cases, a shortage of land to farm or a desire to found a trading post were not the principal spurs to colonization. Occasionally, founding colonies could serve as a mechanism for a city-state to rid itself of undesirable people whose presence at home was causing social unrest. The Spartans, for example, colonized Taras (modern Taranto) in southern Italy in 706 B.C. with a group of illegitimate sons whom they could not successfully integrate into their citizen body. Like the young men of Thera, these unfortunate outcasts certainly did not go out as colonists by their own choice.

Greeks participating in international trade by sea in the Archaic Age increased their homeland’s contact with other peoples, especially in Anatolia and the Near East, and these interactions led to changes in life in Greece in this period. Greeks admired and envied these older civilizations for their wealth, such as the famous gold treasures of the Phrygian kingdom of Midas, and for their cultural accomplishments, such as the lively pictures of animals on Near Eastern ceramics, the magnificent temples of Egypt, and the alphabet from Phoenicia. During the early Dark Age, Greek artists had stopped portraying people or other living creatures in their designs. The pictures they saw on pottery imported from the Near East in the late Dark Age and early Archaic Age influenced them to begin once again to depict figures in their paintings on pots. The style of Near Eastern reliefs and freestanding sculptures also inspired creative imitation in Greek art of the period. When the improving economy of the later Archaic Age allowed Greeks to revive monumental architecture in stone, temples for the worship of the gods inspired by Egyptian sanctuaries represented the most prominent examples of this new trend in erecting large, expensive buildings. In addition, the Greeks began to mint coins in the sixth century B.C., a technology they learned from the Lydians of Anatolia, who had invented coinage as a form of money in the previous century. Long after this innovation, however, much economic exchange continued to be made through barter, especially in the Near East. Economies that relied primarily on currency for commerce and payments took centuries to develop.

Knowledge of the technology of writing was the most dramatic contribution of the ancient Near East to Greece as the latter region emerged from its Dark Age. As mentioned previously, Greeks probably learned the alphabet from the Phoenicians to use it for record keeping in business and trade, as the Phoenicians did, but they soon started to employ it to record literature, above all Homeric poetry. Since the ability to read and write remained unnecessary for most purposes in the predominately agricultural economy of Archaic Greece, and since there were no public schools, few people at first learned the new technology of letters as the representations of sounds and linguistic meaning.

Competition for international markets significantly affected the fortunes of larger Greek city-states during this period. Corinth, for example, grew prosperous from its geographical location controlling the narrow isthmus of land connecting northern and southern Greece. Since ships plying the east–west sea-lanes of the Mediterranean preferred to avoid the stormy passage around the tip of southern Greece, they commonly offloaded their cargoes for transshipment on a special roadbed built across the isthmus and then reloaded onto different ships on the other side of the strip of land. Small ships may even have been dragged over the roadbed from one side of the isthmus to the other. Corinth became a bustling center for shipping and earned a large income from sales and harbor taxes. It also earned a reputation and income as the foremost shipbuilding center of Archaic Greece. In addition, by taking advantage of its deposits of fine clay and the expertise of a growing number of potters, Corinth developed a thriving export trade in pottery painted in vivid colors. It is not certain whether the people overseas who obtained these objects in large numbers, such as the Etruscans in central Italy, prized the pots themselves as foreign luxury items or were more interested in whatever may have been shipped inside the pots, such as wine or olive oil. It is clear that Greek painted pots were regularly transported far from their point of manufacture. By the late sixth century B.C., however, Athens began to displace Corinth as the leading Greek exporter of fancy painted pottery, evidently because consumers came to prefer designs featuring the red color for which the chemical composition of Athens’s clay was better suited than Corinth’s.

The Greeks were always careful to solicit approval from the gods before setting out from home, whether for commercial voyages or formal colonization. The god most frequently consulted about sending out a colony, as in the case of Cyrene, was Apollo, in his sanctuary at Delphi, a hauntingly scenic spot in the mountains of central Greece (fig. 4.1). The Delphic sanctuary began to be internationally renowned in the eighth century B.C. because it housed an oracular shrine in which a prophetess, the Pythia, spoke the will of Apollo in response to questions from visiting petitioners. The Delphic oracle operated for a limited number of days over nine months of the year, and demand for its services was so high that the operators of the sanctuary rewarded generous contributors with the privilege of jumping to the head of the line. The great majority of visitors to Delphi consulted the oracle about personal matters, such as marriage, having children, and other personal issues, but city-states could also send representatives to ask about crucial decisions, such as whether to go to war. That Greeks hoping to found a colony felt they had to secure the approval of Apollo of Delphi demonstrates that the oracle was held in high esteem as early as the 700s B.C., a reputation that continued to make the oracle a force in Greek international affairs in the centuries to come.

Identifying the reasons for the changes in Greek politics that led to the gradual emergence of the city-state in the Archaic Age remains a challenge. The surviving evidence mainly concerns Athens, which was not a typical city-state in significant aspects, particularly in the large size of its population. Much of what we can say about the structuring of the early Greek city-state as a kind of social, political, and religious organization therefore applies solely to Athens. Other city-states certainly emerged under varying conditions and with different results. Nevertheless, it seems possible to draw some general conclusions about the slow process through which city-states began to emerge starting around the middle of the eighth century B.C.

Fig. 4.1: This view shows the theater and the remains of the temple of Apollo at Delphi, below a looming cliff and overlooking a deep valley. This dramatic landscape was a sacred location, home to the internationally famous oracle of the god, which private individuals and political states alike consulted when making important decisions, from getting married to going to war. Wikimedia Commons.

The economic revival of the Archaic Age and the growth in the population of Greece that were taking place by this time certainly gave momentum to the process. Men who managed to acquire fortunes from success in commerce and agriculture could now demand a greater say in political affairs from the social elite, who claimed preeminence based on their current prestige and riches and, if these first two markers of status seemed insufficient, the past glory of their families. Theognis of Megara, a sixth-century B.C. poet whose verses also reflect earlier conditions, gave voice to the distress of members of the elite who felt threatened by the ability of members of the non-elite to use their newly made riches to force their way into the highest level of society: “Men today honor possessions, and elite men marry into ‘bad’ [that is, non-elite] families and ‘bad’ men into elite families. Riches have mixed up lines of breeding . . . and the good breeding of the citizens is becoming obscured” (Theognidea, lines 189–190). This complaint bordered on dishonesty because it obscured the traditional interest of the elite in amassing wealth, but it did reveal the growing tension between those elite members of society who were accustomed to enjoying prominence from the status of their family and those in the nonelite who wanted to gain social status through upward mobility based on the material success they had built for themselves through their own efforts.

The great increase in population in this era probably came mostly in the ranks of the non-elite, especially the relatively poor. Their families raised more children, who could help to farm more land, so long as it was available for the taking in the aftermath of the depopulation of the early Dark Age. Like the Zeus in Hesiod’s Theogony, who acted in response to the injustice of his ruthless father Kronos in swallowing his own children, the growing number of people now owning some property apparently reacted against what they saw as unacceptable inequity in the leadership of the elite, whose members evidently tended to behave as if they were petty kings in their local territory. In Hesiod’s words, they were “swallowing bribes” to inflict what seemed like “crooked” justice on oppressed people with less wealth and power (Works and Days, lines 38–39, 220–221). This concern for equity and fairness on the part of those hoping to improve their lot in life gave a direction to the social and political pressures created by the growth of the population and the general improvement in economic conditions.

For the city-state to be created as a political institution in which all free men had a share, members below the level of the social elite had to insist that they deserved equitable treatment, even if members of the elite were to retain leadership positions and direct the implementation of policies agreed on by the group. The implementation of the concept of citizenship as the basis for the city-state and the extension of citizen status to all freeborn members of the community responded to that demand. Citizenship above all carried certain legal rights, such as being able to exercise freedom of speech and to vote in political and legislative assemblies, to elect officials, to have access to courts to resolve disputes, to have legal protection against enslavement by kidnapping, and to participate in the religious and cultural life of the city-state. The degree of participation in politics open to the poorest men varied among different city-states. The ability to hold public office, for example, could be limited in some cases to owners of a certain amount of property or wealth. Most prominently, citizen status distinguished free men and women from slaves and metics (freeborn foreigners who were officially granted limited legal rights and permission to reside and work in a city-state that was not their homeland). Thus, even poor citizens had a distinction setting themselves apart from these groups not endowed with citizenship, a status in which they could take pride despite their poverty.

It is of course true that social and economic inequality among male citizens persisted as part of life in the Greek city-state despite the legal guarantees of citizenship. The incompleteness of the equality that underlay the political structure of the city-state also revealed itself in the status of citizen women, despite the value that their citizenship represented for them. Women became citizens of the city-states in the absolutely crucial sense that they had an identity, social status, and local rights denied metics and slaves. The important difference between citizen and noncitizen women was made clear in the Greek language, which included a term meaning “female citizen” (politis, the feminine of politēs, “male citizen”), in the existence of certain religious cults reserved for citizen women only, and in legal protection for female citizens against being kidnapped and sold into slavery. Citizen women also could defend their interests in court in disputes over property and other legal wrangles, although they could not represent themselves at trial and had to have men speak for their interests, a requirement that, however, reveals their inequality under the law. The traditional paternalism of Greek society—men acting as “fathers” to regulate the lives of women and safeguard their interests as defined by men—demanded that every woman have an official male guardian (kyrios) to protect her physically and legally. In line with this assumption about the need of women for regulation and protection by men, women were granted no rights to participate in politics. They never attended political assemblies, nor could they vote. They did hold certain civic priesthoods, however, and they had access along with men to the initiation rights of the popular cult of the goddess Demeter at Eleusis near Athens. This internationally renowned cult, about which more will be said later, served in some sense as a safety valve for the pressures created by the remaining inequalities of life in Greek city-states, because it offered to all regardless of class its promised benefits of protection from evil and a better fate in the afterworld.

Despite the limited equality characteristic of the Greek city-state, the creation of this new form of political organization nevertheless represented a significant break with the past, and the extension of at least some political rights to the poor deserves recognition as a truly remarkable development. It took a long time for poor male citizens to gain all the political access and influence that they wanted, and there was always resistance from a faction of the elite. Still, no matter how slow or incomplete this change was, it was unprecedented in the ancient world. In my opinion, despite the limitations and despite how long it took for this change to reach its full development, it would be unfair to the ancient Greeks to deny them the credit for working to implement this principle that is so widely praised—if not always honored—in our world.

Unfortunately, we cannot identify with certainty the forces that led to the emergence of the city-state as a political institution in which even poor men had a vote on political matters. The explanation long favored by many scholars made a set of military and social developments, called the “hoplite revolution,” responsible for the general widening of political rights in the city-state, but more recent research on military history has undermined the plausibility of this theory. Hoplites were infantrymen clad in metal body armor and helmets (fig. 4.2), and they constituted the heavy strike force of the citizen militias that had the main responsibility of defending Greek city-states in this period; professional armies were as yet unknown, and mercenaries were uncommon in Greece. Hoplites marched into combat shoulder to shoulder in a rectangular formation called a phalanx, which bristled with the spears of its soldiers positioned in ranks and files. Staying in line and working as part of the group was the secret to successful phalanx tactics. A good hoplite, in the words of the seventh-century B.C. poet Archilochus, was “a short man firmly placed upon his legs, with a courageous heart, not to be uprooted from the spot where he plants his feet” (Fragment 114). As Homer’s Iliad shows, Greeks had been fighting in formation for a long time before the Archaic Age, but until the eighth century, only leaders and a relatively small number of their followers could afford to buy metal weapons, which the use of iron was now making more affordable; militiamen provided their own arms and armor. Presumably these new hoplites, since they paid for their own equipment and trained hard to learn phalanx tactics to defend their community, felt they—and not just the members of the elite—were entitled to political rights in return for their contribution to “national defense.” According to the theory of a hoplite revolution, these new hoplite-level men forced the elite to share political power by threatening to refuse to fight and thereby cripple the community’s military defense.

Fig. 4.2: Heavily armed infantrymen (hoplites) in the citizen-militias of Greek city-states wore metal helmets like these, which protected their heads but restricted their vision and hearing. The holes along the edges were to attach a lining to cushion the rigid headgear. The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore.

The theory of a hoplite revolution correctly assumes that new hoplites had the power to demand an increased political say for themselves, a development of great significance for the development of the city-state as an institution not solely under the power of a small circle of the most prominent male citizens. The theory of a hoplite revolution cannot explain, however, one crucial question: Why were poor men and not only hoplites given (admittedly sometimes only gradually) the political right of voting on policy in the city-state? Most men in the new city-states were too poor to qualify as hoplites. Nor had the Greeks yet developed navies, the military service for which poor men would provide the manpower in later times, when a fleet was a city-state’s most effective weapon. If being able to make a contribution to the city-state’s defense as a hoplite was the only way to earn the political rights of citizenship, the elites and the “hoplite class” had no obvious reason to grant poor men the right to vote on important matters. And history shows that dominant political groups do not like to split their power with those whom they consider their inferiors. Anthropologists and psychologists today may debate, as they do, to what extent, if any, human nature includes an innate tendency for us to share with others, but politics is barren ground on which to search for examples of power sharing happening spontaneously.

Yet poor men nevertheless did become politically empowered citizens in many Greek city-states, with local variations on whether a man had to own a certain amount of land to have full political rights, whether eligibility for higher public offices required a certain level of income, and how long it took for changes to be made to empower poor men politically. In general, however, all male citizens, regardless of their level of wealth, eventually were entitled to attend, speak in, and cast a vote in the communal assemblies in which policy decisions for city-states were made and officials were elected. That poor men gradually came to participate in the assemblies of the city-states means that they were citizens possessing the basic component of political equality. The hoplite revolution fails as a complete explanation of the development of the city-state above all because it cannot account for the elite’s sharing this right with poorer citizens. Furthermore, the emergence of large numbers of men wealthy enough to afford hoplite armor seems to belong to the middle of the seventh century B.C., well after the period when the city-state as an innovative form of political organization was first coming into existence.

No thoroughly satisfactory alternative or complement to the theory of hoplite revolution has yet emerged to explain the origins of the political structure of the Greek city-state. The laboring free poor—the workers in agriculture, trade, and crafts—contributed much to the economic strength of the city-state, but it is hard to see how their value as laborers could have been translated into political rights. The better-off elements in society certainly did not extend the rights of citizenship to the poor out of any romanticized vision of poverty as spiritually noble. As the contemporary lyric poet Alcaeus phrased what Aristodemus of Sparta reportedly said, “Money is the man; no poor man ever counts as good or honorable” (Fragment 360).

It seems likely that placing too much emphasis on the development of hoplite armor and tactics in the Archaic Age misrepresents the reality of Greek warfare in this early period. In the Dark Age, few men could have afforded metal body armor, and military tactics presumably reflected this fact, with most soldiers accustomed to gear fashioned from leather or even thick cloth as the best protection available to them. Since the numbers of poorer men far exceeded those of the wealthy, any leader wishing to assemble a significant force would have had to rely on the ranks of poor men. Even poorly armed men could form a formidable force against better-armed opponents if their numbers were great enough. Lightly armed combatants in the eighth century B.C.—even those only throwing rocks, wielding staves, and brandishing farming implements as weapons—could have helped their city-state’s contingent of hoplites to sway the tide of battle against an opposing force. The battle scenes in Homer’s Iliad frequently depict fighters throwing rocks at the enemy, and with effect; even the great heroes pick up stones to hurl at their armored foes, expecting to knock them out with the blow and often succeeding. In short, light-armed citizens could significantly shore up the defense of their city-state.

If it is true that poor, lightly armed men were a significant factor in Dark Age warfare, this importance could have persisted until well into the Archaic Age and the time of the development of the city-state, as it took a long time for hoplite armor and weapons to become common. And even after more men had become sufficiently prosperous to afford hoplite equipment, they still would have been well outnumbered by those poorer than they. Early hoplite forces, therefore, may have been only the “fighters in the front” (promachoi), spearheading larger forces of less heavily armed troops assembled from poorer men. In this way, the contribution of the poor to the defense of the city-state as part of its only military force at this date—a citizen militia—would have been essential and worthy of citizenship.

Another significant boost to extending political rights to the poor sometimes came from the sole rulers, called tyrants, who seized power for a time in some city-states and whose history will be discussed in the next chapter. Tyrants could have used grants of citizenship to poor or disenfranchised men as a means of increasing popular support for their regimes.

Furthermore, it seems possible that the elite in Greek society had become less cohesive as a political group in this period of dramatic change, splintering deeply as its members competed more and more fiercely with one another for status and wealth. Their lack of unity then weakened the effectiveness of their opposition to the growing idea bubbling up from the ranks of the poor that it was unjust to exclude them from political participation. When the poor agitated for power in the citizen community, on this view, there would have been no united front of members of the elite and hoplites to oppose them, making compromise necessary to prevent destructive civil unrest.

In this context, it makes sense to think that this unprecedented change in the nature of politics in ancient Greece was fueled by the concern for justice and equality that Hesiod’s poems express. The majority of people evidently agreed that it was no longer acceptable for others to tell them what to do without their consent, because, at some fundamental level, they were all equal or at least similar in their contributions to the community and therefore deserved a more-equal or at least a more-similar say in how things were run. This communal tendency toward greater egalitarianism in politics corresponded, on the local level, to the Panhellenism found in the emergence of the Olympic Games and rejected the attitude portrayed in the episode in Homer’s Iliad when Odysseus beat Thersites for publicly criticizing Agamemnon (as mentioned in chapter 3).

Whatever the precise interplay of its different causes may have been, the hallmark of the politics of the developed Greek city-states certainly became the practice of male citizens making decisions communally. Members of the social elite continued to be powerfully influential in Greek politics even after city-states had come into existence, but the unprecedented political sway that non-elite citizens over time came to exercise in city-states constituted the most remarkable feature of the change in the political organization of Greek society in the Archaic Age. This entire process was gradual, as city-states certainly did not suddenly emerge fully formed around 750 B.C. Three hundred years after that date, for example, the male citizens of Athens were still making major changes in their political institutions to disperse political power more widely among the male citizen body and to give more rights to poorer male citizens. What is worth remembering is that this change happened at all.

As already mentioned, freedom remained only an elusive dream for many in ancient Greece even after the emergence of the city-state in the Archaic Age. The evidence for slavery in the earlier Dark Age already reveals complex relationships of dependency among free and unfree people. The language of the epics of Homer and Hesiod mentions people called dmōs, doulē, and douleios, all of whom were dependent and unfree to a greater or lesser degree. Some dependent people featured in the poems seem more like inferior members of the owners’ households than living, breathing possessions. They live under virtually the same conditions as their superiors and enjoy a family life of their own. Others who were taken prisoner in war apparently were reduced to the status of complete slavery, meaning they were wholly under the domination of their owners, who benefited from the captives’ labor. These slaves counted as property—chattel—not as people. If the descriptions in these poems reflect actual conditions in the Dark Age, chattel slavery was not, however, the primary form of dependency in Greece during that period.

The creation of citizenship as a category to define membership in the exclusive group of people constituting a Greek city-state inevitably highlighted the contrast between those included in the category of citizens and those outside it. Freedom from control by others was a necessary precondition to becoming a citizen with full political rights, which in the city-states meant above all being a freeborn adult male. The strongest contrast citizenship produced, therefore, was that between free (eleutheros) and unfree or slave (doulos). In this way, the development of a clear idea of personal freedom in the formation of the city-state as a new political form may paradoxically have encouraged the complementary development of widespread chattel slavery in the Archaic Age. The rise in economic activity in this period probably also encouraged the importation of slaves by increasing the demand for labor. In any case, slavery as it developed in the Archaic Age reduced most unfree persons to a state of absolute dependence; they were the property of their owners. As Aristotle later categorized slaves, they were a “sort of living possession” (Politics 1253b32). He concluded that slavery was natural because there were people who lacked the capacity for reason that was necessary for a person to be a free agent, although he reluctantly had to grant the power of arguments rejecting the assertion that some people by their nature did not deserve to be free.

Captives taken in war presented a problem for Aristotle’s analysis of natural slavery, because they had been free before the accident of defeat in battle subjected them to the loss of their previous liberty; it was not a deficiency in reasoning that had turned them into chattel. Nevertheless, all Greek city-states accepted that prisoners of war could be sold as slaves (if they were not ransomed by their families). Relatively few slaves seem to have been born and raised in the households of those for whom they worked in Greece. Most slaves were bought on the international market. Slave traders imported chattel slaves to Greece from the rough regions to the north and east, where foreign raiders and pirates captured non-Greeks. The local bands in these areas would also raid their neighbors and drag off captives to sell to slave dealers. The dealers would then sell their purchases in Greece at a profit. Herodotus reported that some of the Thracians, a group of peoples living to the north of mainland Greece, “sold their children for export” (The Histories 5.6). This report probably meant that one band of Thracians sold children captured from other bands of Thracians, whom the first group considered different from themselves. The Greeks lumped together all foreigners who did not speak Greek as “barbarians” (barbaroi)—people whose speech sounded to Greeks like the repetition of the meaningless sounds “bar, bar.” Barbarians, the Greeks thought, were not all alike; they could be brave or cowardly, intelligent or dim-witted. But they were not, by Greek standards, civilized. Greeks, like Thracians and other slaveholding peoples, found it easier to enslave people whom they considered different from themselves and whose ethnic and cultural otherness made it easier to disregard their shared humanity. Greeks also enslaved fellow Greeks, however, especially those defeated in war, but these Greek slaves were not members of the same city-state as their masters. Rich families prized Greek slaves with some education because they could be made to serve as tutors for children, for whom there were no publicly financed schools in this period.

It took until about 600 B.C. for chattel slavery to become the norm in Greece. Eventually, slaves became cheap enough that families of moderate means could afford one or two. Nevertheless, even wealthy Greek landowners never acquired gangs of hundreds of slaves comparable in size to those that maintained Rome’s water system under the Roman Empire or that worked large plantations in the southern United States before the American Civil War. For one thing, maintaining a large number of slaves year-round in ancient Greece would have been uneconomical because the cultivation of the crops grown there generally called for short periods of intense labor punctuated by long stretches of inactivity, during which slaves would have to be fed even while they had no work to do.

By the fifth century B.C., however, the number of slaves in some city-states had swollen to as much as one-third of the total population. This percentage means that, of course, small landowners, their families, and hired free workers still performed the majority of work in Greek city-states. The special system of slavery in Sparta, as will be explained later, provides a rare exception to this situation. Rich Greeks everywhere regarded working for someone else for wages as disgraceful, but their attitude did not correspond to the realities of life for many poor people, who had to earn a living at any work they could find.

Like free workers, chattel slaves did all kinds of labor. Household slaves, often women, had the physically least dangerous existence. They cleaned, cooked, fetched water from public fountains, helped the wife with the weaving, watched the children, accompanied the husband as he did the marketing (as was the Greek custom), and performed other domestic chores. Yet they could not refuse if their masters demanded sexual favors. Slaves who worked in small manufacturing businesses, like those of potters or metalworkers, and slaves working on farms often labored alongside their masters. Rich landowners, however, might appoint a slave supervisor to oversee the work of their other slaves in their fields while they remained in town. The worst conditions of life for slaves obtained for those men leased out to work in the narrow, landslide-prone tunnels of Greece’s few silver and gold mines. The conditions of their painful and dangerous jobs were dark, confined, and backbreaking. Owners could punish their slaves whenever they felt like it, even kill them without fear of meaningful sanctions. (A master’s murder of a slave was regarded as at least improper and perhaps even illegal in Athens of the Classical period, but the penalty may have been no more than ritual purification.) Beatings severe enough to cripple a working slave and executions of able-bodied slaves were probably infrequent because destroying such useful pieces of property made no economic sense for an owner.

Some slaves enjoyed a measure of independence by working as public slaves (dēmosioi, “belonging to the people”) owned by the city-state instead of an individual. They lived on their own and performed specialized tasks. In Athens, for example, public slaves later had the responsibility for certifying the genuineness of the city-state’s coinage. They also performed distasteful tasks that required the application of force to citizens, such as serving as the assistants to the citizen magistrates responsible for arresting criminals. The city’s official executioner was also a public slave in Athens. Slaves attached to temples also lived without individual owners because temple slaves belonged to the god of the sanctuary, for which they worked as servants, as depicted, for example, in the drama Ion written by the Athenian playwright Euripides and performed on stage in the late fifth century B.C.

Under the best conditions, household slaves with humane masters might live lives free of violent punishment. They might even be allowed to join their owners’ families on excursions and attend religious rituals, such as sacrifices. Without the right to a family of their own, however, without being able to own property, without legal or political rights, they lived an existence alienated from regular society. In the words of an ancient commentator, chattel slaves lived lives of “work, punishment, and food” (Pseudo-Aristotle, Oeconomica 1344a35). Their labor helped maintain the economy of Greek society, but their work rarely benefited themselves. Yet despite the misery of their condition, Greek chattel slaves—outside Sparta—almost never revolted on a large scale, perhaps because they were of too many different nationalities and languages and too far from their homelands to organize themselves for rebellion and escape from their households to return to their lands of origin. Sometimes owners freed their slaves voluntarily, and some owners promised freedom at a future date to encourage their slaves to work hard in the meantime. Freed slaves did not become citizens in Greek city-states, however, but instead became members of the population of resident foreigners, the metics. They were expected to continue to help out their former masters when called upon.

The emergence of slavery on a large scale in the Greek city-state made households bigger and added new responsibilities for women, especially rich women, whose lives were circumscribed by the responsibility of managing their households. As partners in the maintenance of the family with their husbands, who spent their time outside farming, participating in politics, and meeting their male friends, wives were entrusted with the management of the household (oikonomia, whence comes our word economics). They were expected to raise the children, supervise the preservation and preparation of food, keep the family’s financial accounts, direct the work of the household slaves, and nurse them when they were ill. A major task was to weave textiles for clothing, which was expensive, especially the colorfully patterned clothes that women wore, when their families could afford such finery (fig. 4.3). Households thus depended on women, whose work permitted the family to be economically self-reliant and the male citizens to participate in the public life of the polis.

Poor women worked outside the home, often as small-scale merchants in the public market (agora) that occupied the center of every settlement. Only at Sparta did women have the freedom to participate in athletic training along with men. Women played their major role in the public life of the city-state by participating in religious rituals, state festivals, and funerals. Certain festivals were reserved for women only, especially in the cult of the goddess Demeter, whom the Greeks credited with teaching them the indispensable technology of agriculture. As priestesses, women also fulfilled public duties in various official cults; for example, women officiated as priestesses in more than forty such cults in Athens by the fifth century B.C. Women holding these posts often enjoyed considerable prestige, practical benefits such as a salary paid by the state, and greater freedom of movement in public.

Upon marriage, women became the legal wards of their husbands, as they previously had been of their fathers while still unmarried. Marriages were arranged by men. A woman’s guardian—her father, or if he were dead, her uncle or her brother—would commonly betroth her to another man’s son while she was still a child, perhaps as young as five. The engagement was an important public event conducted in the presence of witnesses. The guardian on this occasion repeated the phrase that expressed the primary aim of marriage: “I give you this woman for the plowing [procreation] of legitimate children” (Lucian, Timon 17). The marriage itself customarily took place when the girl was in her early teens and the groom ten to fifteen years older. Hesiod advised a man to marry a virgin in the fifth year after her puberty, when he himself was “not much younger than thirty and not much older” (Works and Days, lines 697–705). A legal marriage consisted of the bride’s going to live in the house of her husband. The procession to his house was as close to the modern idea of a wedding ceremony as Greek marriage offered. The woman brought with her a dowry of property (perhaps land yielding an income, if she were wealthy) and personal possessions that formed part of the new household’s assets and could be inherited by her children. Her husband was legally obliged to preserve the dowry and to return it in case of a divorce. Procedures for divorce were more concerned with power than law: A husband could expel his wife from his home, while a wife, in theory, could on her own initiative leave her husband to return to the guardianship of her male relatives. Her freedom of action could be constricted, however, if her husband used force to keep her from leaving. Monogamy was the rule in ancient Greece, and a nuclear family structure (that is, husband, wife, and children living together without other relatives in the same house) was common, except at Sparta, although at different stages of life a married couple might have other relatives living with them. Citizen men could have sexual relations without penalty with slaves, foreign concubines, female prostitutes, or (in many city-states) willing preadult citizen males. Citizen women had no such sexual freedom, and adultery carried harsh penalties for wives as well as their illicit male partners. Sparta, as often in Greek social norms, was an exception: There, a woman who was childless could have sex for reproduction with another man, so long as her husband agreed.

Fig. 4.3: This Archaic Age marble statue from Athens depicting an unmarried girl (korē) was displayed in public, as was customary for art at the time, probably as a gift to a divinity. The traces of paint on her hair and carefully draped clothing hint at the bright coloring of ancient Greek statues; the colors usually fade or disappear over the centuries. Wikimedia Commons.

More than anything else, a dual concern to regulate marriage and procreation and to maintain family property underlay the placing of the legal rights of Greek women and the conditions of their citizenship under the guardianship of men. The paternalistic attitude of Greek men toward women was rooted in the desire to control human reproduction and, consequently, the distribution of property, a concern that had gained special urgency in the reduced economic circumstances of the Dark Age. Hesiod, for instance, makes this point explicitly in relating the myth of the first woman, named Pandora (Theogony, lines 507–616; Works and Days, lines 42–105). According to the legend, Zeus, the king of the gods, created Pandora as a punishment for men when Prometheus, a divine being hostile to Zeus, stole fire from Zeus to give it to human beings, who had previously lacked that technology. Pandora subsequently loosed “evils and diseases” into the previously trouble-free world of men by removing the lid from the jar or box the gods had filled for her. Hesiod then refers to Pandora’s descendants, the female sex, as a “beautiful evil” for men ever after, comparing them to drones who live off the toil of other bees while devising mischief at home. But, he goes on to say, any man who refuses to marry to escape the “troublesome deeds of women” will come to “destructive old age” without any children to care for him (Theogony, lines 603–605). After his death, moreover, his relatives will divide his property among themselves. A man must marry, in other words, so that he can sire children to serve as his support system in his old age and to preserve his holdings after his death by inheriting them. Women, according to Greek mythology, were for men a necessary evil, but the reality of women’s lives in the city-state incorporated social and religious roles of enormous importance.