An Athenian blunder in international diplomacy set in motion the greatest military threat that the ancient Greeks had ever faced and put the freedom of Greece at desperate risk from invasions by enormous forces of the Persian Empire. In 507 B.C. the Athenians were afraid that the Spartans would again try to intervene to support the oligarchic faction that was resisting the new democratic reforms of Cleisthenes. Looking for help against Greece’s number-one power, the Athenians sent ambassadors to ask for a protective alliance with the king of Persia, Darius I (ruled 522–486 B.C.). The Persian Empire was by far the largest, richest, and most militarily powerful state in the entire ancient world. At Sardis, the Persian headquarters in western Anatolia, the Athenian emissaries met with a representative of the king, his local governor in the region (a satrap, in Persian terminology). When the satrap heard their plea for an alliance to help protect them against the Spartans, he replied, “But who in the world are you and where do you live?” (Herodotus, The Histories 5.73). From the Persian perspective, the Athenians were so insignificant that this major Persian imperial administrator had never heard of them. Yet within two generations Athens would be in control of what today we call the Athenian Empire. The transformation of Athens from insignificance to international power was startlingly unexpected: It came about over a generation-long period of desperate war that marked the beginning of the Classical Age (500–323 B.C.).

The dynamics of this incident between Athens and Persia expose the forces motivating the conflicts that would dominate the military and political history of mainland Greece throughout the fifth century B.C. First, the two major powers in mainland Greece—Sparta and Athens—remained suspicious of each other. As described in the previous chapter, the Spartans had sent an army to Athens to intervene against Cleisthenes and his democratic reforms in the last decade of the sixth century B.C.; on their mission in defense of freedom (as they would have justified it), they had forced seven hundred Athenian families into exile. But then they had experienced the humiliation of seeing the men of Athens band together to expel their forces, doing public damage to the Spartans’ reputation for invincibility on the battlefield. From then on, the Spartans saw Athens as a hostile state, a feeling naturally reciprocated at Athens. Second, the kingdom of Persia had expanded westward all the way to Anatolia and had become the master of Greek city-states along its coast, installing tyrants as puppet rulers of the conquered Greeks there. With Persians now controlling the eastern end of the Aegean Sea, the Greeks of the mainland had good reason to worry about Persian intentions concerning their own territories. Since neither the Persians nor the mainland Greeks yet knew much about each other, their mutual ignorance opened the door to explosive misunderstandings.

The Athenian ambassadors dispatched to Sardis naively assumed that Athens was going to become more or less an equal partner with the Persian king in a defensive alliance because Greeks were accustomed to making treaties on those sorts of terms. When the satrap demanded that, to conclude the agreement, Athens’s representatives must offer tokens of earth and water, the Athenians in their ignorance of the Persians at first did not understand the significance of these symbolic gestures. From the Persian perspective, they indicated an official recognition of the superiority of the king. Since Persian royal ideology maintained that the king was preeminent above everyone else in the world, he did not make alliances on equal terms with anyone. When the Athenian emissaries realized what the gestures meant, they reluctantly went ahead with this public admission of their state’s inferiority because they were unwilling to return to their countrymen without an agreement in hand. Once they had returned home, however, they discovered that the citizens in the Athenian assembly were outraged at their envoys’ symbolic submission to a foreign power. Despite this angry reaction, the assembly never sent another embassy to the satrap in Sardis to announce that Athens was unilaterally dissolving the pact with the king. Darius therefore had no indication that the relationship had changed; as far as he knew, the Athenians remained voluntarily allied to him as inferiors and still owed him the deference and loyalty that he expected all mere mortals everywhere to pay to his royal status. The Athenians, on the other hand, continued to think of themselves as independent and unencumbered by any obligation to the Persian king.

507 B.C.: Athenians send ambassadors to ask for an alliance with Persia.

500–323 B.C.: The Greek Classical Age.

499 B.C.: Beginning of the Ionian revolt.

494 B.C.: Final crushing of the Ionian revolt by the Persians.

490 B.C.: Darius sends Persian force to punish Athenians, who win the battle of Marathon.

483 B.C.: Discovery of large deposits of silver in Attica; Athenians begin to build large navy at instigation of Themistocles.

482 B.C.: Ostracism of Aristides (recalled in 480 B.C.).

480 B.C.: Xerxes leads massive Persian invasion of Greece; Persian victory at the battle of Thermopylae and Greek victory at the battle of Salamis.

479 B.C.: Battle of Plataea in Greece and battle of Mycale in Anatolia.

478 B.C.: Spartans send Pausanias to lead Greek alliance against Persians.

477 B.C.: Athens assumes leadership of the Greek alliance (Delian League).

475 B.C.: Cimon returns the bones of the hero Theseus to Athens.

465 B.C.: Devastating earthquake in Laconia leads to helot revolt in Messenia.

465–463 B.C.: Attempt of the island of Thasos to revolt from the Delian League.

462 B.C.: Cimon leads Athenian troops to help Spartans, who reject them.

461 B.C.: Ephialtes’ reforms to increase the direct democracy of Athenian government.

450s B.C.: Hostilities between Athens and Sparta; institution of stipends paid to jurors and other magistrates at Athens.

454 B.C.: Enormous losses of Delian League forces against Persians in Egypt; transfer of league’s treasury from island of Delos to Athens.

451 B.C.: Passage of Pericles’ law on citizenship.

450 B.C.: End of overseas expeditions by Delian League forces against Persian Empire.

447 B.C.: Athenian building program begins.

446–445 B.C.: Athens and Sparta make a peace treaty meant to last thirty years.

443 B.C.: Pericles’ main political opponent ostracized.

441–439 B.C.: Island of Samos attempts to revolt from Delian League.

430s B.C.: Increasing political tension at Athens as Sparta threatens war.

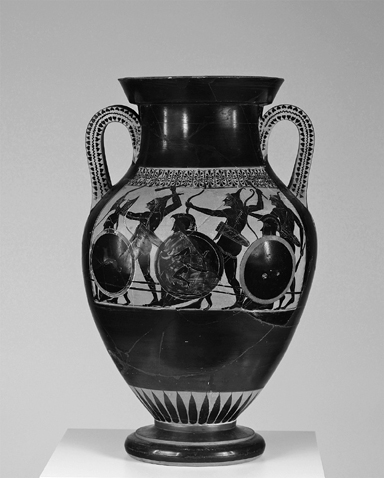

This fiasco in diplomacy propelled a sequence of explosive events culminating in destructive invasions of mainland Greece by the enormous army and navy of the Persian Empire. That vast kingdom outstripped mainland Greece in every category of material resources, from precious metals to soldiers. The Greeks by this point could field citizen-militia forces of heavily armed and lightly armed infantry, archers and javelin throwers, cavalry, and warships, and the frequent conflicts between city-states had trained them in effective tactics (fig. 6.1). At the same time, the disparity in numbers between the Persian Empire and the Greeks meant that war between them pitted the equivalent of an elephant against a small swarm of mosquitoes. In such a mismatched conflict of unequals, a Greek victory seemed improbable, even impossible. Equally improbable, given the independent Greek city-states’ propensity toward disunity and even mutual hostility, was that a coalition of thirty-one Greek city-states—a small minority of the Greeks—would band together to resist the enormous forces of the enemy and stay united despite their fear and disagreements over the years of struggle against a monstrously stronger enemy.

The Persian Empire was a relatively recent creation. The ancestral homeland of the Persians lay in southern Iran, and their language stemmed from the Indo-European family of tongues; the language of today’s Iran is a descendant of ancient Persian. Cyrus (ruled 560–530 B.C.) became the founder of the empire by overthrowing the monarchy of the Medes. The Median kingdom, centered in what is today northern Iran, had emerged in the late eighth century B.C., and the army of the Medes had joined that of the Babylonians in destroying the Assyrian kingdom in 612 B.C. The Median kingdom had then extended its power as far as the border of Lydia in central Anatolia. By taking over Lydia in 546, Cyrus also acquired dominion over the Greek city-states on the western coast of Anatolia that the Lydian king Croesus (ruled c. 560–546 B.C.) had previously subdued.

By the reign of Darius I, the Persian kingdom covered thousands of miles in every direction, stretching from west to east from Egypt and Turkey through Mesopotamia and Iran to Afghanistan and the western border of India, and from north to south from the southern borders of central Asia to the Indian Ocean. Numbering in the tens of millions, its diverse population spoke countless different languages. The empire took its administrative structure from Assyrian precedents, and its satraps ruled enormous territories with little direct attention from the king as to how they treated his subjects. The satraps’ duties were to keep order, enroll troops when needed, and send revenues to the royal treasury. The imperial system exacted taxes in food, precious metals, and other valuable commodities from the various regions of the empire; the soldiers that it assembled from far and wide came with an enormous variety of different equipment, training, and languages of command, making the generalship of the army a daunting challenge in devising tactical cooperation and communications among troops with little or no experience working together.

Fig. 6.1: This “black-figure” vase depicts a battle line in which the heavily armed infantrymen in metal helmets crouch behind their shields while unarmored archers shoot arrows at the enemy. This combined-arms form of attack meant that men who could not afford expensive metal body armor could still contribute to their city-state’s defense by learning to use less costly missile weapons. The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore.

The revenues extracted from its many subject peoples made the Persian monarchy wealthy beyond comparison. Everything about the king was meant to emphasize his grandeur and superiority to everyone else in the world: His purple robes were more splendid than anyone’s; the red carpets spread for him to walk upon could not be stepped on by anyone else; his servants held their hands before their mouths in his presence to muffle their breath so that he would not have to breathe the same air as they did; in the sculpture adorning his palace, he was depicted as larger than any other human being. To display his concern for his loyal subjects, as well as the gargantuan scale of his resources, the king provided meals for some fifteen thousand nobles, courtiers, and other followers every day, although he himself ate behind a curtain hidden from the view of his guests. The Greeks, in awe of the Persian monarch’s power and lavishness, simply referred to him as “the Great King.”

The Persian kings did not regard themselves as gods but rather as the agents of the supreme god of Persian religion, Ahura Mazda. Persian religion, based on the teachings of the prophet Zoroaster, was dualistic, conceptualizing the world as the arena for a constant battle between good and evil. Unlike other peoples of the ancient Near East and the Greeks, the Persians shunned animal sacrifice. Fire, kindled on special altars, formed an important part of their religious rituals. The religion of ancient Persia survives in the modern world as Zoroastrianism, whose adherents have preserved the central role of fire in its practice. Despite their autocratic rule, the ancient Persian kings usually did not interfere with the religious worship or everyday customs of their subjects; they realized that this sort of interference with people’s traditional beliefs and practices could only lead to instability, the dread of imperial rulers.

The most famous series of wars in ancient Greek history—the so-called Persian Wars, which took place in the 490s and in 480–479 B.C.—broke out with a revolt against Persian control by the Greek city-states of Ionia (the region and the islands on the western coast of Anatolia). As alluded to earlier, the Ionian Greeks had originally lost their independence not to the Persians but to King Croesus of Lydia in the mid-sixth century B.C. As colorfully described by Herodotus in the first book of his Histories, Croesus had been buoyed by this success and his legendary great wealth; the saying “rich as Croesus” still gets used to this day. He next tried to conquer territory in Anatolia that had previously been in the Median kingdom. Before initiating the attack, however, Croesus had requested advice from Apollo’s oracle at Delphi about the advisability of invading a region that the new Persian monarchy was also claiming. The oracle gave the famous response that if Croesus attacked the Persians, he would destroy a great kingdom. Encouraged, Croesus sent his army eastward in 546, but he was defeated and lost his territory, including Ionia, to Cyrus, the Persian king. When Cyrus later allowed Croesus to complain to the Delphic oracle that its advice had been disastrously wrong, the oracle pointedly replied that if Croesus had been truly wise, he would have asked a second question: Whose kingdom was he going to destroy, his enemy’s or his own? Croesus shamefacedly had to admit that the oracle was right.

By 499 B.C., the city-states in Ionia had begun a revolt against the Greek tyrants that the Persian kings, after conquering the area, had installed as collaborators to maintain control over their conquests there. An Ionian leader traveled to mainland Greece seeking military aid for the rebellion. The Spartan king Cleomenes ruled out any chance of help from his citystate after he saw the map that the Ionian had brought and learned that an attack on the heartland of Persia (today in modern Iran) would require a march of three months inland from the Ionian coast. He, like the other Spartans and most Greeks in general, had previously had no accurate idea of the geography and dimensions of the Near East. The men of the Athenian assembly, in contrast to the Spartan leaders, voted to join the city-state of Eretria on the neighboring island of Euboea in sending troops to fight alongside the Ionians in their revolt. The Athenian militiamen proceeded as far as Sardis, Croesus’s old capital and current Persian headquarters for Ionia. Their attack ended with the city in flames, including a famous religious sanctuary. However, the Athenians and Eretrians soon returned home when a Persian counterattack made the Ionian allies lose their coordination and effectiveness as a fighting force. Subsequent campaigns by the Persian king’s commanders crushed the Ionian revolt entirely by 494. King Darius then sent his general Mardonius to reorganize Ionia, where he now surprised the locals by installing democratic governments to replace the unpopular tyrannies. Since the Persian king was only interested in loyalty from his subjects, he was willing to learn from his mistakes and let the Ionians be governed locally as they pleased if they would then remain loyal and stop rebelling against overall Persian control.

King Darius flew into a rage when he was informed that the Athenians had aided the Ionian revolt: It was bad enough that they had dared attack his kingdom, but they had done it after having indicated their submission and loyalty to him by offering the tokens of earth and water to his satrap. Insignificant though the Greeks were in his eyes, he vowed to avenge their disloyalty as a matter of justice, to set things right in the world that by nature he was supposed to rule. The Greeks later claimed that, to keep himself from forgetting his vow of punishment in the press of his many other concerns as the ruler of a huge kingdom, Darius ordered one of his slaves to say to him three times at every meal, “Lord, remember the Athenians” (Herodotus, The Histories 5.105). In 490 B.C. Darius dispatched a flotilla of ships carrying troops to punish the Athenians and the Eretrians. His men burned Eretria and then landed on the nearby northeastern coast of Attica near a village called Marathon. The Persians had brought with them the elderly Hippias, the exiled son of the Athenian tyrant Pisistratus, expecting to reinstall him as ruler of Athens as their puppet. Since the Persian soldiers vastly outnumbered the citizen-militia of Athens, the Athenians asked the Spartans and other Greek city-states for military help. The Athenian courier dispatched to Sparta became famous because he ran the 140 miles from Athens to Sparta in less than two days. But by the time the battle of Marathon took place, the only troops to arrive were a contingent from the small city-state of Plataea in Boeotia, the region just north of Athenian territory. The Plataeans felt that they owed the Athenians a debt of gratitude for having protected them from their hostile neighbors the Thebans thirty years earlier, and they had the great courage to try to pay that debt even when the price of their moral integrity looked likely to be destruction at the hands of the Persians.

Everyone expected the Persians to win. The Greek soldiers, who had never seen Persians in battle array before, grew afraid just gazing at their (to Greek eyes) frighteningly outlandish outfits, which included pants; Greek men wore only tunics, going barelegged. Moreover, the number of Persian troops at the battle of Marathon was huge compared to the size of the combined Athenian and Plataean contingents. The Athenian commanders—a board of ten generals elected each year as the civil and military leaders of Athens plus one other military official—felt enormous pressure to act, because they feared that the disparity in forces might induce the assembly to surrender rather than fight, or that the oligarchic sympathizers among the Athenian elite might try to strike a treacherous deal with the Persian king, whose recent arrangements to install local democracies in Ionia demonstrated that he was always ready to come to terms with anyone who could guarantee peaceful subjects. The Athenians and Plataeans therefore prepared for an attack on the wider line of the Persians by thinning out the center of their own line of soldiers while putting more men on the wings. Carefully planning their tactics to minimize the time their soldiers would be exposed to the fire of Persian archers, the generals, led by Miltiades of Athens (c. 550–489 B.C.), sent their hoplites against the Persian line at a dead run. Mastering the natural urge to panic and run away as they approached the killing zone, the Greek hoplites clanked across the Marathon plain in their metal armor under a hail of arrows. Once engaged in hand-to-hand combat with the Persians, the Greek infantrymen overcame their opponents thanks to their longer weapons and superior armor. In a furious struggle, the strengthened wings of the Greek army slaughtered the Persians opposite them and then turned inward to crush the Persian center from the flanks. They then drove the Persians back into a swamp, where any invaders unable to escape to their ships could be picked off one by one.

The Athenian army then hurried on foot the more than twenty miles from the battlefield at Marathon to the fortification wall of Athens to guard the city against a naval attack by the Persian fleet. Today’s long footraces called marathons commemorate in their name and distance this famous trek by Greek soldiers in 490 B.C. When the Persians sailed home without taking Athens, the Athenians (at least those who favored democracy) rejoiced in disbelief. The Persians, whom they had feared like no others, had withdrawn. For decades afterward, the greatest honor an Athenian man could claim was to say he had been a “Marathon fighter.”

The symbolic importance of the battle of Marathon far outweighed its military significance. The defeat of his punitive expedition enraged Darius because it insulted his prestige, not because it represented any threat to the security of his kingdom. The ordinary Athenian citizens who made up the city-state’s army, on the other hand, had dramatically demonstrated their commitment to preserving their freedom by refusing to capitulate to an enemy whose reputation for power and wealth had made a disastrous Athenian defeat appear certain. The unexpected victory at Marathon gave an unparalleled boost to Athenian self-confidence, and the city-state’s soldiers and leaders thereafter always boasted that they had stood resolute before the feared barbarians even though the Spartans had not come in time to help them. They also forever after celebrated the Plataeans as noble allies.

Map 5. The Persian Wars

This newly won confidence helped steel the population of Athens to join in the resistance to the gigantic Persian invasion of Greece that arrived in 480 B.C. Darius had vowed the invasion as revenge for the defeat at Marathon, but it took so long to assemble forces from all over the far-flung Persian kingdom that he died before his retaliatory strike could be launched. His son, Xerxes I (ruled 486–465), therefore led the massive invasion force of infantry and ships against the Greek mainland. So huge was Xerxes’ army, the Greeks later claimed, that it required seven days and seven nights of continuous marching on a temporary bridge lashed together from boats and pontoons to cross the Hellespont, the narrow passage of sea between Anatolia and mainland Greece. Xerxes expected the Greek states simply to surrender without a fight once they realized the size of his forces. The city-states in northern and central Greece did just that because their location placed them directly in the line of the invading Persian forces, while the small size of their populations left them without any hope of effective defense. The important Boeotian city-state of Thebes, about forty miles north of Athens, also supported the Persian invasion, probably hoping to gain an advantage over its Athenian neighbors in the aftermath of the expected Persian victory; Thebes and Athens had of course long been hostile to one another over whether Plataea should be free of Theban dominance.

Thirty-one Greek states, most of them located in central and southern Greece, formed a military coalition to fight the Persian invasion; they chose Sparta as their leader because it fielded Greece’s most formidable hoplite army. The coalition also sought aid from Gelon, the tyrant of Syracuse, the most powerful Greek city-state on Sicily. The appeal failed, however, when Gelon demanded command of the Greek forces in return for his assistance, a price the Spartan and Athenian leaders were unwilling to meet. In this same period Gelon was engaged in a struggle with Carthage, a powerful Phoenician city on the coast of North Africa, over territory in Sicily. In 480 B.C. Gelon’s forces defeated a massive Carthaginian expedition in battle at Himera, on the island’s northern coast. It is possible that the Carthaginian expedition to Sicily and the Persian invasion of mainland Greece were purposely coordinated to embroil the Greek world simultaneously in a two-front war in the west and the east.

The Spartans showed their courage this same year when three hundred of their men led by Leonidas, along with a number of other Greeks, held off Xerxes’ huge army for several days at the narrow pass called Thermopylae (“warm gates”) on the eastern coast of central Greece. Xerxes was flabbergasted that this paltry force did not immediately retreat when confronted with his magnificent army. The Spartan troops characteristically refused to be intimidated. When one of Xerxes’ scouts was sent ahead to observe the situation at the pass, he reported that the Spartans were standing casually in front of their fortification, leisurely combing their long hair. The Persians were astonished at this behavior, but it was in fact customary for Spartan soldiers to fix their flowing locks as a mark of pride before proceeding into battle. Their defiant attitude was summed up by the reputed response of a Spartan hoplite to the remark that the Persian archers were so numerous that their arrows darkened the sky in battle. “That’s good news,” said the Spartan; “we’ll get to fight in the shade” (Herodotus, The Histories 7.226). The pass was so narrow that the Persians could not employ their superior numbers to overwhelm the Greek defenders, who were more skilled at close-in fighting. Only when a local Greek, hoping for a reward from the Persian king, revealed to him a secret route around the choke point was the invading army able to massacre the Greek defenders by attacking them from the front and the rear simultaneously. The Persian army then continued its march southward into Greece; the “Three Hundred” had failed to stop the Persians, but they had demonstrated that they would die before surrendering.

Plan 1. Attica Showing Battle of Marathon (490 B.C.) and Battle of Salamis (480 B.C.)

The Athenians soon proved their resolve and courage, too. Rather than surrender when Xerxes arrived in Attica with his army, they abandoned their city. Women, children, and noncombatants packed up their belongings as best they could and evacuated to the northeast coast of the Peloponnese. Xerxes then sacked and burned Athens as punishment for their defiance. The destruction of Athens frightened the Peloponnesian Greeks in the alliance, and their desire to retreat southward with the fleet to defend their peninsula threatened to destroy the unity of the resistance. The Greek warships at this point were anchored off the west coast of Athenian territory, where the Athenian commander Themistocles (c. 528–462) realized they could use to their advantage the topography of the narrow channel of water between the coast and the island of Salamis, close offshore. As in the infantry battle at the pass at Thermopylae, the confined space of the channel would prevent the vastly larger Persian navy from attacking with all its ships at once and overwhelming the Greeks with their smaller number of warships. He therefore compelled his disheartened colleagues in the alliance to do battle with the Persian fleet in the battle of Salamis in 480 B.C. by sending a message to the Persian king to block both ends of the channel to prevent the Peloponnesians from sailing away.

Athens supplied the largest contingent to the Greek navy at Salamis because the assembly had been financing the construction of warships ever since a rich strike of silver had been made in Attica in 483. The proceeds from the silver mines went to the state, and, at the urging of Themistocles, the assembly had voted to use the financial windfall to build a navy for defense, rather than to disburse the money to all the citizens. The warship of the time was an expensive vessel called a trireme, a name derived from its having three stacked banks of oarsmen on each side for propulsion in battle. Built for speed, these specialized weapons were so cramped and unstable that they had to be pulled up on shore every night; there was no room for anyone to sleep or eat on board. One hundred and seventy rowers were needed to propel a trireme, which fought by smashing into enemy ships with a metal-clad ram attached to the bow. Most of the rowers could not see out and never knew from moment to moment if they were about to be skewered by an enemy attack, and anxiety was so raw that men could lose control of their bowels onto the heads of their colleagues below as they rowed into battle, facing the prospect of an enemy ram smashing through their ship’s side to crush them to death at any moment. Triremes also usually carried a complement of ten hoplite warriors and four archers on their decks to engage the enemy crews in combat when the ships became entangled. Officers and other crew brought the total of men on board to two hundred.

The tight space of the Salamis channel not only prevented the Persians from using all their warships at once but also minimized the advantage of their ships’ greater maneuverability. The heavier Greek ships could employ their underwater rams to sink the less-sturdy Persian craft, whose rams did not have as much mass behind them. When Xerxes observed that the most energetic of his naval commanders appeared to be the one woman among them, Artemisia, the ruler of Caria (today the southwest corner of Turkey), he reportedly remarked, “My men have become women, and my women, men” (Herodotus, The Histories 8.88).

The Greek victory at Salamis in 480 induced Xerxes to return to Persia; it was now clear that a quick victory over the Greeks was not going to happen, especially at sea, where the Greek fleet had proved it was better than his. It was not wise for the Great King to be away too long from the court and its potential rivals for his throne if he wished to keep a firm grip on his power. So Xerxes went home, but he left behind an enormous land army under his best general, Mardonius, as well as a startling (to the Greeks) strategic move: Early in 479 he extended an offer to the Athenians to make peace with them (and only them). If they came to terms, he would leave them in freedom (meaning no tyrant ruling as a Persian stooge), pay to rebuild the Athenian sanctuaries that his troops had burned, and give the Athenians another land to rule in addition to their own. The Greeks should not have been surprised; after all, the Persian king had reversed his policy in Ionia after having crushed the rebels, replacing the puppet tyrants there with democracies to ensure more peaceful conditions in his dealings with the Ionian city-states. Xerxes made this offer because he recognized that, with the Athenian fleet on his side, the rest of the Greeks would have no chance except to submit to Persian control.

Xerxes’ offer was genuine, and it was seductive; as the king’s ally, the Athenians could have reconstructed their wrecked city with his endless supply of money and enjoyed his support in dominating their rivals and enemies in Greece. The Spartans were frantic with fear when they heard about the offer; they realized how tempting it was. They probably acknowledged, to themselves in secret, that they would have taken it if it had been made to them. Astonishingly, however, the Athenian assembly refused to take the Persian deal. They told the Spartans that there was no pile of gold large enough and no territory beautiful enough to bribe them to collaborate with the Persians to bring “slavery” to their fellow Greeks. No, they said, we insist on fighting for retribution from our enemies who burned the images and houses of our gods. Our Greekness, they continued, pledges us to reject this temptation: “We all share the same ancestry and language, we have sanctuaries and sacrifices to the gods that we share, and we share a common way of life” (Herodotus, The Histories 8.144). This definition of Greek identity meant so much to them, then, that they were willing to risk complete destruction—the massive Persian land army remained close by—rather than abandon their sense of who they were and what their place in the world was. Their refusal to compromise their ideals deserves recognition as a decisive moment in ancient Greek history.

Mardonius then marched the Persian army into Attica—and sent the offer again. When Lycidas, a member of the Athenian Council of Five Hundred, recommended that it be accepted, his fellow council members and the men gathered around to listen to the debate stoned him to death. When the women in the city heard about what Lycidas had proposed, they banded together to attack his home and stone his wife and children. Emotions were raw because everyone knew how high the stakes were. The people of Athens then evacuated their city and land for the second time, and, with the offer rejected again, Mardonius then laid waste to everything left standing in the urban center and the countryside of Athens.

Meanwhile, the Spartans had built a wall across the isthmus that connected the Peloponnese peninsula to central Greece, planning to hunker down there to block the Persians from advancing into their territory; they were ready to abandon the rest of the Greeks beyond the isthmus. They decided to leave their wall behind and march north to face the enemy only after being bluntly reminded by the Athenians that Athens could still accept the Persian king’s offer even at this point and add their intact fleet to his to become the rulers of Greece. Reluctantly, the Spartans sent their infantry, commanded by a royal son named Pausanias (c. 520–470 B.C.), to join the other Greeks still in the alliance to face the much larger Persian land army on the plains of Boeotia north of Athens; Mardonius had chosen to take up a position near Plataea because the terrain was favorable to the disposition of his forces. There, the Greeks and the Persians met in the final great land battle of the Persian Wars in 479. The sight of so many Persians in battle array at first dismayed the majority of the Spartan infantry, and to avoid meeting these frightening troops directly, the Spartan commanders asked to switch positions in the line with the Athenians so that they could face the Persians’ allies instead. The Athenians agreed. In the end, however, one stubborn band of Spartan warriors refused to leave their place despite the imminent danger to their lives from Persian attacks, inspiring their wavering comrades to stand and fight the numerically superior and visually intimidating enemy. When Mardonius, the Persian commander, was killed, his army lost heart, and the Greeks won a tremendous victory at the battle of Plataea. In an amazing coincidence, on the same day (so the Greeks later remembered it) the Greek fleet stationed off the coast of southwestern Anatolia at a place called Mycale caught the Persian fleet unprepared for battle. The Greeks courageously disembarked their crews to attack the disorganized Persians on shore. The surprise succeeded, and the Persians were routed at the battle of Mycale.

The battles of Plataea and Mycale in 479 proved the tipping points in expelling the invasion forces of the Persian Empire from Greece. The Persian army and navy could have recovered from the losses of men and materiel; their empire was too large and too rich to be seriously disabled by these setbacks for very long. The loss of morale seems to have been the key. The Greeks, despite the fears and disagreements that nearly overcame them at critical moments, had summoned the dedication and determination not to give in; they broke the spirit of the enemy, the secret to winning wars in the hand-to-hand conditions of the killing zones of ancient warfare.

The coalition of thirty-one Greek city-states had stunned their world: Despite the huge difficulties they constantly created for themselves in cooperating with one another, in the end they fought together to protect their homeland and their independence from the strongest power in the world. The Greek fighters’ superior weapons and armor and their commanders’ insightful use of topography to counterbalance their enemy’s greater numbers help to explain their victories on the military level. What is truly memorable about the Persian Wars, however, is the decision of the citizen militias of the thirty-one Greek city-states to fight in the first place—and their determination never to quit in the face of doubts and temptations. They could easily have surrendered and agreed to become Persian subjects to save themselves. Instead, these Greek warriors chose to strive together against apparently overwhelming odds. Their bravery found support in the encouragement to fight, even the demand not to give up, offered by noncombatants in their communities, such as the women of Corinth, who as a group offered public prayers to the goddess Aphrodite for the Greek cause. Since the Greek forces included not only the wealthiest men and hoplites but also thousands of poorer men, who fought as light-armed troops and rowed the warships, the effort against the Persians cut across social and economic divisions. The Greek decision to fight the Persian Wars demonstrated courage inspired by a deep devotion to the ideal of political freedom, which had emerged in the preceding Archaic Age. The Athenians, who twice allowed the Persians to ravage and burn their homes and property rather than make a deal with the Persian king, showed a determination that filled their enemies—and everyone else—with awe.

The struggle against the Persian invasion had generated a rare interval of interstate cooperation in ancient Greek history. The two most powerful city-states, Athens and Sparta, had, with difficulty, put aside their mutual suspicions stemming from their clash at the time of the reforms of Cleisthenes to share the leadership of the united Greek military forces. Their attempt to continue this cooperation after the repulse of the Persians, however, ended in failure, despite the lobbying of pro-Spartan Athenians who believed that the two city-states should be partners rather than rivals. Out of this failure arose the so-called Athenian Empire, a modern label invented to indicate the military and financial dominance Athens eventually came to exercise over numerous other Greek states in an alliance that had originated as a voluntary coalition against Persia.

Following its victories in 479 B.C., the members of the Greek coalition decided to continue as a naval alliance aimed at expelling the Persian outposts that still existed in far northern Greece and western Anatolia, especially Ionia. The Spartan Pausanias, the victor of the battle of Plataea, was chosen to lead the first expedition in 478. He was soon accused of arrogant and violent behavior toward both his allies and local Greek citizens in Anatolia, especially women. Some modern scholars believe that he was framed by his personal and political enemies; whatever the truth, contemporaries evidently found it easy to believe that such outrageous conduct was a threat from Spartans in positions of power, now that they were spending long periods away from home on distant military campaigns. What does seem true is that Spartan men’s long years of harshly regimented training often left them poorly prepared to operate humanely and effectively once they had been freed from the constraints imposed by their way of life at home, where they were always under the scrutiny of the entire Spartan community. In short, there seems to have been a real danger that Spartan men would put aside their respect for their society’s traditional restraint and self-control once they left behind the borders of their city-state and were operating on their own.

By 477, the Athenian leader Aristides (c. 525–465 B.C.) had successfully persuaded the other Greeks in the alliance to demand Athenian leadership of the continuing fight against the Persians in the Aegean region. The leaders at Sparta decided to give up their position at the head of the alliance without protest because, in the words of the Athenian historian Thucydides (c. 460–400 B.C.), “They were afraid any other commanders they sent abroad would be corrupted, as Pausanias had been, and they were glad to be relieved of the burden of fighting the Persians. . . . Besides, at the time they still thought of the Athenians as friendly allies” (The Peloponnesian War 1.95). The Spartans’ ongoing need to keep their army at home most of the time to guard against helot revolts also made it risky for them to keep up prolonged operations outside the Peloponnese.

The Greek alliance against Persia now took on a permanent organizational structure under Athenian leadership. Member states swore a solemn oath never to desert the coalition. The members were predominantly located in northern Greece, on the islands of the Aegean Sea, and along the western coast of Anatolia—the areas most exposed to Persian attack. Most of the independent city-states of the Peloponnese, on the other hand, remained in their long-standing alliance with the Spartans, an arrangement that had been in existence since well before the Persian Wars. Thus, Athens and Sparta each now dominated a separate coalition of allies. Sparta and its allies, whose coalition modern historians refer to as the Peloponnesian League, had an assembly to set policy, but no action could be taken unless the Spartan leaders agreed to it. The alliance headed by Athens also had an assembly of representatives to make policy. Members of this alliance were in theory supposed to make decisions in common, but in practice Athens was in charge because it furnished the greatest number of warships in the alliance’s navy. The special arrangements made to finance the Athenian-led alliance’s naval operations promoted Athenian domination. Aristides set the different levels of dues (today called “tribute”) that the various member states were to pay each year, based on their size and prosperity. The alliance’s funds were kept on the Aegean island of Delos, in the temple of Apollo, to whom the whole island was sacred, and consequently the alliance is today customarily referred to as the Delian League.

Over time, more and more of the members of the Delian League paid their dues in cash rather than by going to the trouble of furnishing warships. Most members of the alliance preferred this option because it strained their capacities to maintain the construction infrastructure required to build ships as specialized and expensive as triremes, and it was exhausting to train crews to the high level of teamwork required to work triple banks of oars as they drove the ships forward, back, and obliquely in complicated tactical formations. Athens, far larger than most of the allies, had the shipyards and skilled workers to build triremes in large numbers, as well as a large population of men eager to endure tough training so that they could earn pay as rowers. Therefore, Athens built and manned most of the alliance’s warships, using the dues of allies to supplement its own contribution. The Athenian men serving as rowers on these warships came from the poorest social class, that of the laborers (thetes), and their invaluable contribution to the navy earned them not only money but also additional political importance in Athenian democracy, as naval strength increasingly became the city-state’s principal source of military power. Athens continued to be able to muster larger numbers of hoplite infantry than many smaller city-states, but over time its fleet became its most powerful force.

Since most allies eventually had only limited naval strength or no warships of their own at all, many individual members of the Delian League had no effective recourse if they disagreed with decisions made for the league as a whole under Athenian leadership. By dispatching the superior Athenian fleet to compel discontented allies to adhere to league policy and to continue paying their annual dues, the men of the Athenian assembly came to exercise the dominant power. The modern reference to allied dues as tribute is meant to indicate the compulsory nature of these payments. As Thucydides observed, rebellious allies “lost their independence,” making the Athenians as the league’s leaders “no longer as popular as they used to be” (The Peloponnesian War 1.98–99).

The most egregious instance of Athenian compulsion of a reluctant ally was the case of the city-state of the island of Thasos in the northern Aegean Sea. Thasos in 465 B.C. unilaterally withdrew from the Delian League after a dispute with Athens over control of gold mines on the neighboring mainland. To force the Thasians to keep their sworn agreement to stay in the league forever, the Athenians led allied forces against them in a protracted siege, which ended in 463 with the island’s surrender. As punishment, the league forced Thasos to pull down its defensive walls, give up its warships, and pay enormous tribute and fines.

The Delian League did accomplish its principal strategic goal: Within twenty years after the battle of Salamis in 480, league forces had expelled almost all the Persian garrisons that had continued to hold out in city-states along the northeastern Aegean coast and had driven the Persian fleet from the Aegean Sea, ending the direct Persian military threat to Greece for the next fifty years. Athens meanwhile grew stronger from its share of the spoils captured from Persian outposts and the dues paid by its members. By the middle of the fifth century B.C., league members’ annual payments totaled the equivalent of perhaps $300 million in contemporary terms (assuming $120 as the average daily pay of an ordinary worker today).

The male citizens meeting in the assembly decided how to spend the city-state’s income, and for a state the size of Athens (around thirty to forty thousand adult male citizens) the annual income from the alliance combined with other revenues from the silver mines at Laurion and taxes on international commerce meant general prosperity. Rich and poor alike had a self-interested stake in keeping the fleet active and the allies paying for it. Privately wealthy leaders such as Cimon (c. 510–450 B.C.), the son of Miltiades, the victor of Marathon, enhanced their prestige by commanding successful league campaigns and then spending their share of the spoils on benefactions to the people of Athens. Cimon, for example, reportedly paid for the foundations of the massive defensive walls that eventually connected the city’s urban core with its harbor at Piraeus several miles away. Such financial contributions to the common good were expected of wealthy and prominent men. Political parties did not exist in ancient Athens, and political leaders formed informal circles of friends and followers to support their ambitions. Disputes among these ambitious leaders often stemmed more from competition for election to the highest public offices of the city-state and influence in the assembly than from disagreements over political or financial policy. Arguments tended to concern how Athens should exercise its growing power internationally, not whether it should refrain from interfering with the affairs of the other members of the Delian League in the pursuit of Athenian interests. The numerous Athenian men of lesser means who rowed the Delian League’s ships came to depend on the income they earned on league expeditions. Since these men represented the numerically largest group in the male population eligible to vote in the assembly of Athens, where decisions were rendered by majority vote, they could make certain that assembly votes were in their interest. If the interests of the allies did not coincide with theirs, the allies were given no choice but to acquiesce to official Athenian opinion concerning league policy. In this way, alliance was transformed into empire, despite Athenian support of democratic governments in some allied city-states previously ruled by oligarchies. From the Athenian point of view, this transformation was justified because it kept the alliance strong enough to continue to carry out the overall mission of the Delian League: protecting Greece from the Persians.

Poorer men of the thete class powered the Athenian fleet, and as a result of their essential role in national defense, both their military and their political importance grew in the decades following the Persian War. As these poorer citizens came to recognize that they provided the foundation of Athenian security and prosperity, they apparently felt the time had come to make the administration of justice at Athens just as democratic as the process of making policy and passing laws in the assembly, which was open to all male citizens over eighteen years old. Although at this time the assembly could serve as a court of appeals, most judicial verdicts were rendered by the nine annual magistrates of the city-state—the archons—and the Areopagus council of ex-archons. The nine archons had been chosen by lottery rather than by election since 487 B.C., thus making access to those offices a matter of random chance and not liable to domination by wealthy men from Solon’s highest income level, who could afford expensive electoral campaigns. Filling public offices by lottery was felt to be democratic because it gave an equal chance to all eligible contestants; the gods were thought to oversee this process of random selection to make sure the choices were good ones. But even democratically selected magistrates were susceptible to corruption, as were the members of the Areopagus. A different judicial system was needed if those men who decided cases were to be insulated from pressure by socially prominent people and from bribery by those rich enough to buy a favorable verdict. That laws were enacted democratically at Athens meant little if they were not applied fairly and honestly.

The final impetus to a reform of the judicial system came from a crisis in foreign affairs. The change had its roots in a tremendous earthquake near Sparta in 465 B.C. The tremors of the earth killed so many Spartans that the helots of Messenia, the Greeks in the western Peloponnese who had long ago been subjugated by the Spartans, instigated a massive revolt against their weakened masters; as previously mentioned, the Spartan citizen population never recovered from the losses. By 462 the revolt had become so serious that the Spartans appealed to Athens for military help, despite the chill that had fallen over relations between the two city-states since the days of their cooperation against the Persians. The tension between the former allies had arisen because rebellious members of the Delian League had received at least promises of support from the leaders at Sparta, who felt that Athens was growing powerful enough to someday threaten Spartan interests in the Peloponnese. Cimon, the hero of the Delian League’s campaigns, marshaled all his prestige to persuade a reluctant Athenian assembly to send hoplites to help the Spartans defend themselves against the Messenian helots. Cimon, like many among the Athenian elite, had always been an admirer of the Spartans, and he was well known for signaling his opposition to proposals in the assembly by saying, “But that is not what the Spartans would do” (Plutarch, Cimon 16). His Spartan friends let him down, however, by soon changing their minds and sending him and his army in disgrace back to Athens. Spartan leaders feared that the democratically inclined Athenian rank and file might decide to help the helots escape from Spartan domination, even over Cimon’s opposition.

The humiliating Spartan rejection of their help outraged the Athenian assembly and provoked openly hostile relations between the two states. The disgrace it brought to Cimon carried over to the elite in general, thereby establishing a political climate ripe for further democratic reforms. A man named Ephialtes promptly seized the moment in 461 B.C. and convinced the assembly to pass measures limiting the power of the Areopagus. The details are obscure, but it appears that up to this time the Areopagus council had held authority to judge accusations of misconduct brought against magistrates, a competence referred to as “guardianship of the laws.” The Areopagus was constituted by ex-magistrates, who would presumably have been on generally good terms with current magistrates, the very ones whom they were supposed to punish when the officeholders acted unjustly or made corrupt decisions. This connection created at least the appearance of a conflict of interest, and instances of illegal conduct by magistrates being whitewashed or excused by the Areopagus no doubt had occurred. The reforms apparently removed the guardianship of the laws from the Areopagus, although the council remained the court for premeditated murder and wounding, arson, and certain offenses against the religious cults of the city-state.

The most significant of Ephialtes’ reforms was the establishment of a judicial system of courts manned by juries of male citizens over thirty years old, chosen by lottery to serve in trials for a one-year term. Previously, judicial power had belonged primarily to the archons and the Areopagus council of ex-archons, but now that power was largely transferred to the jurors, a randomly chosen cross section of the male citizen body, six thousand men in all, who were distributed into individual juries as needed to handle the case load. Under this new judicial system, the magistrates were still entitled to render verdicts concerning minor offenses, the Areopagus had its few special judicial competencies, and the council and assembly could take action in certain cases involving the public interest. Otherwise, the citizen-manned courts were given wide jurisdiction. Their juries in practice defined the most fundamental principles of Athenian public life because they interpreted the law by deciding on their own how it should be applied in each and every case. There were no judges to instruct the jurors and usually no prosecutors or defense lawyers to harangue them, although a citizen could be appointed to speak for the prosecution when a magistrate was on trial for misconduct in office, or when the case explicitly involved the public interest.

In most cases citizens brought the charges, and the only government official in court was a magistrate to keep fights from breaking out during the trial. All trials were concluded in a single day, and jurors made up their own minds after hearing speeches by the persons involved. They swore an oath to pay attention and judge fairly, but they were the sole judges of their own conduct as jurors and did not have to undergo a public examination of their actions at the end of their term of service, as other officials in Athenian democracy regularly did. Improperly influencing the outcome of cases by bribing jurors was made difficult because juries were so large, numbering from several hundred to several thousand. Nevertheless, jury tampering apparently was a worry, because in the early fourth century B.C. the system was revised to assign jurors to cases by lottery and not until the day of the trial.

Since few, if any, criminal cases could be decided by scientific or forensic evidence of the kind used in modern trials, persuasive speech was the most important element in the legal proceedings. The accuser and the accused both had to speak for themselves in Athenian court, although they might pay someone else to compose the speech that they would deliver, and they frequently asked others to speak in support of their arguments and as witnesses to their good character. The characters and civic reputations of defendants and plaintiffs were therefore always relevant, and jurors expected to hear about a man’s background and his conduct as a citizen as part of the information necessary to discover where truth lay. A majority vote of the jurors ruled. No higher court existed to overrule their decisions, and there was no appeal from their verdicts. The power of the court system after Ephialtes epitomized the power of Athenian democracy in action. As a trial-happy juror boasts in Aristophanes’ comic play of 422 B.C. about the Athenian judicial system, “Our power in court is the equivalent of a king’s!” (Wasps, pp. 548–549).

The structure of the new court system reflected underlying principles of what scholars today call the “radical” democracy of Athens in the mid-fifth century B.C. This system involved widespread participation by a cross section of male citizens, selection of the participants by lottery at random for most public offices, elaborate precautions to prevent corruption, equal protection under the law for individual citizens regardless of wealth, and the authority of the majority over any minority or individual when the vital interests of the state were at stake. This last principle appears most dramatically in the official procedure for exiling a man from Athens for ten years, called ostracism. Every year the assembly voted on whether to go through this procedure, which gets its name from the word ostraca, meaning “pieces of broken pottery”; these shards were inscribed with names of candidates for expulsion and used as ballots. If the vote on whether to hold an ostracism in a particular year was affirmative, all male citizens on a predetermined day could cast a ballot on which they had scratched the name of the man they thought should be exiled. If six thousand ballots were cast, whichever man was named on the greatest number was compelled to go live outside the borders of Attica for ten years. He suffered no other penalty, and his family and property could remain behind undisturbed. Ostracism was not a criminal penalty, and men returning from their period of exile enjoyed undiminished rights as citizens.

Ostracism existed because it helped protect the Athenian system from real or perceived threats. At one level, it provided a way of removing a citizen who seemed extremely dangerous to democracy because he was totally dominating the political scene, whether because he was simply too popular and thus a potential tyrant by popular demand, or whether he was genuinely subversive. This point is made by a famous anecdote concerning Aristides, who set the original level of dues for the members of the Delian League. Aristides had the nickname “the Just” because he was reputed to be so fair-minded. On the day of the balloting for an ostracism, an illiterate man from the countryside handed Aristides a potsherd, asking him to carve on it the name of the citizen he wanted to ostracize. “Certainly,” said Aristides. “Which name should I write?” “Aristides,” replied the countryman. “All right,” remarked Aristides as he proceeded to inscribe his own name. “But tell me, why do you want to ostracize Aristides? What has he done to you?” “Oh, nothing. I don’t even know him,” sputtered the man. “I’m just sick and tired of hearing everybody refer to him as ‘the Just’” (Plutarch, Aristides 7).

In most cases, ostracism served to identify a prominent man who could be made to take the blame for a failed policy that the assembly had originally approved but that was now causing extreme political turmoil. Cimon, for example, was ostracized after the disastrous attempt to cooperate with Sparta during the helot revolt of 462 B.C. There is no evidence that ostracism was used frivolously, despite the story about Aristides, and probably no more than several dozen men were actually ostracized before the practice fell into disuse after about 416, when two prominent politicians colluded to have a nonentity ostracized instead of one of themselves. Ostracism is significant for understanding Athenian democracy because it symbolizes the principle that the interest of the group must prevail over that of the individual citizen when the freedom of the group and the freedom of the individual come into conflict in desperate and dangerous cases. Indeed, the first ostracisms had taken place in the 480s, after the ex-tyrant Hippias had appeared with the Persians at Marathon in 490 and some Athenians feared he would again become tyrant over the community.

Although Aristides was indeed ostracized in 482 and recalled in 480 to fight the Persians, the anecdote about his encounter with the illiterate citizen sounds apocryphal. Nevertheless, it makes a valid point: The Athenians assumed that the right way to protect democracy was always to trust the majority vote of freeborn adult male citizens, without any restrictions on a man’s ability to say what he thought was best for democracy. This conviction required making allowances for irresponsible types like the kind of man depicted in the story about Aristides. It rested on the belief that overall the cumulative political wisdom of the majority of voters would outweigh the eccentricity and irresponsibility of the few.

The idea that democracy at Athens was best served by involving a cross section of the male citizenry received further backing in the 450s B.C. from Pericles (c. 495–429 B.C.), whose mother was the niece of the democratic reformer Cleisthenes and whose father had been a prominent leader. Like Cleisthenes before him, Pericles was a man of privilege who became the most influential leader in the Athens of his era by devising innovations to strengthen the egalitarian tendencies of Athenian democracy. In the 450s he successfully proposed that state revenues be used to pay a daily stipend to men who served on juries, on the Council of Five Hundred established by Cleisthenes, and in other public offices filled by lottery. Before these stipends were mandated, poorer men found it hard to leave their regular work to serve in these time-consuming positions. The amount that jurors and other officials received was a living allowance, not a high rate of pay, certainly no more than an ordinary laborer could earn in a day. Nevertheless, providing this money to them enabled poorer Athenians to serve in government. On the other hand, the most influential public officials—the annual board of ten generals who had responsibility both for military and civil affairs, especially public finances—received no stipends. They were elected by the assembly rather than chosen by lottery, because their posts required expertise and experience; they were not paid because mainly rich men like Pericles, who had received the education required to handle this top job and enjoyed the free time to fill it, were expected to win election as generals. Generals were compensated only by the status and prestige that their office brought them.

Pericles and others of his economic status had inherited enough wealth to spend their time in politics without worrying about money, but remuneration for public service was essential for Athenian democracy if it were truly going to be open to the mass of men who depended on farming or earning wages to feed their families. Pericles’ proposal for state stipends for jurors made him overwhelmingly popular with ordinary citizens. Consequently, beginning in the 450s, he was able to introduce dramatic changes in both Athenian foreign and domestic policy. On the latter front, for instance, Pericles sponsored a law in 451 stating that from then on citizenship would be conferred only on children whose mother and father both were Athenians. Previously, the offspring of Athenian men who married non-Athenian women had been granted citizenship. Wealthy Athenian men from the social elite had regularly married rich foreign women, as Pericles’ own maternal grandfather had done. The new law not only solidified the notion of Athenian identity as special and exclusive but also emphatically recognized the privileged status of Athenian women as possessors of citizenship, putting their citizenship on a par with that of men in the crucially important process of establishing the citizenship of new generations of Athenians. Not long after the passage of the citizenship law, a review of the citizenship rolls of Athens was conducted to expel any persons who had claimed citizenship fraudulently. The advantages of citizenship included, for men, the rights to participate in politics and juries, to influence decisions that directly affected their lives and the lives of their families, to have equal protection under the law, and to own land and houses in Athenian territory. Citizen women had fewer direct rights because they were excluded from politics, had to have their male legal guardian speak for them in court, and were not legally entitled to make large financial transactions on their own. They did, however, enjoy the fundamental guarantees of citizenship: the ability to control property and to have the protection of the law for their persons and their property. Female and male citizens alike experienced the advantage of belonging to a city-state that was enjoying unparalleled material prosperity and an enhanced sense of pride in its communal identity and international power.

The involvement of Pericles in foreign policy in the 450s B.C. is less clear, and we cannot tell how he felt about the massive Athenian intervention in support of a rebel in Egypt trying to overthrow Persian rule there. This expedition, which began perhaps in 460, ended in utter disaster in 454 with the loss of perhaps two hundred ships and their crews, an overwhelming death toll given that each ship had approximately two hundred men on board. Some of these men would have been allies, not Athenians, but the loss of manpower to Athens must have been large regardless. In the aftermath of this catastrophe, the treasury of the Delian League was moved from Delos to Athens, ostensibly to insure its safety from possible Persian retaliation and not simply to make it easier for the Athenian assembly to use the funds. Whatever the real motive behind this change, it signified the overwhelming dominance that Athens had achieved as leader of the league by this time.

The 450s were a period of intense military activity by Athens and its allies. At the same time that Athenian and Delian League allies were fighting in Egypt, they were also on campaign on the eastern Mediterranean seacoast against Persian interests. In this same decade, Pericles also supported an aggressive Athenian foreign policy against Spartan interests in Greece. Athens’s forces were defeated by the Peloponnesians at the battle of Tanagra in Boeotia in central Greece in 457, but its troops subsequently gained control of that region and neighboring Phocis as well. The Athenians won victories over the nearby island of Aegina as well as Corinth, the powerful city-state in the northeastern Peloponnese. When Cimon, who had returned from ostracism, died in 450 while leading a naval force against the Persians on the island of Cyprus, the assembly finally decided to end military campaigns directed at Persian interests and sent no more fleets to the eastern Mediterranean.

Athenian military operations in Greece failed to secure enduring victory over Sparta’s allies in central Greece, and Boeotia and Phocis threw off Athenian control in 447 B.C. In the winter of 446–445, Pericles engineered a peace treaty with Sparta designed to freeze the balance of power in Greece for thirty years and thus preserve Athenian dominance in the Delian League. He was then able to turn his attention to his political rivals at Athens, who were jealous of his influence over the board of ten generals. Pericles’ overwhelming political prominence was confirmed in 443 when he managed to have his chief rival, named Thucydides (not the historian), ostracized instead of himself. Pericles was subsequently elected one of Athens’s generals for fifteen years in a row. His ascendancy was challenged, however, after he rashly took sides in a local political crisis on the island of Samos, which led to a war with that valuable Delian League ally from 441 to 439. The war with Samos was not the first break between Athens and its Delian League allies in the period since 450, when action against the Persians—the main goal of the league in its early years after 478—had ceased to be an active part of the league’s mission. Strains developed between Athens and several allied city-states that wished to leave the league and end their tribute payments, which were no longer paying for open war with Persia, only for defensive power in case of attack, which now seemed unlikely. Pericles’ position apparently was that the league was indeed fulfilling its primary mission of keeping the allies safe from Persia: That no Persian fleet ever ventured far from its eastern Mediterranean home base was proof that the allies had no cause for complaint. Inscriptions from the 440s B.C., in particular, testify to the unhappiness of various Athenian allies and to Athenian determination to retain control over its unhappy partners in the alliance.

When the city-state of Chalcis on the island of Euboea rebelled against the Delian League in 446 B.C., for example, the Athenians soon put down the revolt and forced the Chalcidians to swear to a new set of arrangements. Copies of the terms inscribed on stone were then set up in Chalcis and Athens. The differences in the oaths exchanged by the two sides as recorded in this copy of the inscription found at Athens reveal the imperiousness of Athens’s dominance over its Greek allies in this period:

The Athenian Council and all the jurors shall swear the oath as follows: “I shall not deport Chalcidians from Chalcis or lay waste the city or deprive any individual of his rights or sentence him to a punishment of exile or put him in prison or execute him or seize property from anyone without giving him a chance to speak in court without (the agreement of) the People [that is, the assembly] of Athens. I shall not cause a vote to be held, without due notice to attend trial, against either the government or any private individual whatever. When an embassy [from Chalcis] arrives [in Athens], I shall see that it has an audience before the Council and People within ten days when I am in charge of the procedure, so far as I am able. These things I shall guarantee to the Chalcidians if they obey the People of Athens.” The Chalcidians shall swear the oath as follows: “I shall not rebel against the People of Athens either by trickery or by plot of any kind either by word or by action. Nor shall I join someone else in rebellion and if anyone does start a rebellion, I shall denounce him to the Athenians. I shall pay the dues to the Athenians which I persuade them [to assess], and I shall be the best and truest possible ally to them. And I shall send assistance to the People of Athens and defend them if anyone attacks the People of Athens, and I shall obey the People of Athens.”

—(Crawford and Whitehead no. 134 = IG 3rd ed., no. 40)

While it is clear that the Athenians with this imposed agreement bound themselves to follow rules in dealing with their allies, it is equally unmistakable that the relationship was not on equal terms: Their formerly independent allies were explicitly required to “obey.”

Pericles in the mid-430s B.C. faced an even greater challenge than restive and rebellious allies when Athenian relations with Sparta greatly worsened despite the provisions of the peace that had been struck in 446–445. A stalemate developed when the Spartans finally threatened war unless the Athenians ceased their interference in the affairs of the Corinthian colonies of Corcyra and Potidaea, but Pericles prevailed upon the assembly to refuse all compromises. His critics claimed he was sticking to his hard line against Sparta and insisting on provoking a war in order to revive his fading popularity by whipping up a jingoistic furor in the assembly. Pericles retorted that no accommodation to Spartan demands was possible, because Athenian freedom of action was at stake. By 431, the thirty-years’ peace between Athens and Sparta made in 445 had been shattered beyond repair. The Peloponnesian War (as modern historians call it) between Athens and its allies and Sparta and its allies broke into open hostilities in 431; at that point no one could know that its violence would drag on for twenty-seven years.

Athens reached the height of its power and prosperity in the decades of the mid-fifth century B.C. preceding the Peloponnesian War, the period accordingly referred to today as the city-state’s Golden Age. Private homes, whether in the city or in the countryside, retained their traditionally modest size even during this period of communal abundance. Farmhouses were usually clustered in villages, while homes in the urban center were wedged tightly against one another along narrow, winding streets. Even the residences of rich people followed the same basic design, which grouped bedrooms, storerooms, workrooms, and dining rooms around the one constant in every decent-sized Greek house: an open-air courtyard in the center. The courtyard was walled off from the street, thereby insuring privacy, a prime goal of Greek domestic architecture. Wall paintings or works of art were as yet uncommon as decoration in private homes, with sparse furnishings and simple furniture the rule. Toilet facilities usually consisted of a pit dug just outside the front door, which was emptied by collectors paid to dump manure outside the city at a distance set by law. Poorer people rented houses or small apartments.

Plan 2. Athens near the End of the Fifth Century B.C.

Benefactions donated by the rich provided some public improvements, such as the landscaping with shade trees and running tracks that Cimon paid to have installed in open areas in the city. On the edge of the agora, the central market square and open gathering spot at the heart of the urban area, Cimon’s brother-in-law paid for the construction of the renowned building known as the Painted Stoa. Stoas were narrow buildings open along one side, designed to provide shelter from sun or rain. The crowds of men who came to the agora daily for conversation about politics and local affairs would cluster inside the Painted Stoa, whose walls were decorated with paintings of great moments in Greek history commissioned from the most famous painters of the time, Polygnotus and Mikon. It was appropriate that one of the stoa’s paintings portrayed the battle of Marathon in 490 B.C., in which Cimon’s father, Miltiades, had won glory, because the husband of Cimon’s sister had donated the building to the city. The social values of Athenian democracy called for leaders like Cimon and his brother-in-law to provide such gifts for public use to show their goodwill toward the city-state and thereby earn increased social eminence as their reward. Wealthy citizens were also expected to fulfill costly liturgies (public services), such as providing theatrical entertainment at city festivals or fitting out a fully equipped warship and then serving on it as a commander. This liturgical system for wealthy men compensated to a certain extent for the lack of any regular income or property taxes in peacetime after the reign of the tyrant Pisistratus. (The Assembly could vote to institute a temporary levy on property, the eisphora, to pay war costs.)

Athens received substantial public revenues from harbor fees, sales taxes, its silver mines, and the dues paid by the allies. Buildings paid for by public funds from these sources constituted the most conspicuous architecture in the city of the Classical period of the fifth and fourth centuries B.C. The scale of these public buildings was usually no greater than the size required to fulfill their function, such as the complex of buildings on the agora’s western edge in which the Council of Five Hundred held its meetings and the public archives were kept. Since the assembly convened in the open air on a hillside above the agora, it required no building at all except for a speaker’s platform. In 447, however, at Pericles’ instigation, a great project began atop the Acropolis, the mesalike promontory at the center of the city that towered over the agora. Over the next fifteen years, the Athenians financed the construction of a mammoth gate building with columns, the Propylaea, which straddled the broad entrance to the Acropolis at its western end, and a new Athena temple, the Parthenon, to house a towering image of the goddess (fig. 6.2). These buildings together cost easily more than the equivalent of the total of several years’ dues from the allies, a phenomenal sum to spend for an ancient Greek city-state, regardless of whether the money came from domestic or foreign sources of revenue. The program was so expensive that the political enemies of Pericles blasted him in the assembly for squandering public funds. Scholars disagree about how much, if any, of the finances for this building program came from Athens’s income from the Delian League, as the financial records of the period are incomplete and ambiguous. Some funds certainly were taken from the financial reserves of the goddess Athena, whose sanctuaries, like those of the other gods throughout Greece, received both private donations and public support. However they were paid for, the new buildings made a spectacular impression not only because they were expensive but also because their large scale, decoration, and surrounding open spaces contrasted so vividly with the private architecture of Athens in the fifth century B.C.

Fig. 6.2: In the mid-fifth century B.C., the Athenians built the very expensive Parthenon temple on their city-state’s citadel (the Acropolis) as a second temple honoring their patron goddess Athena and proclaiming their prosperity and military success. The older Athena temple sits to the left of the larger Parthenon in the photo. Wikimedia Commons.

Parthenon, the name of the new temple built for Athena on the Acropolis, meant “the house of the virgin goddess.” As the patron deity of Athens, Athena had long had another sanctuary on the Acropolis honoring her in her role as Athena Polias (“guardian of the city”). The focus of this earlier shrine was an olive tree regarded as the sacred symbol of the goddess, who in this capacity provided for the agricultural and thus the essential prosperity of the Athenians. The temple in the Athena Polias sanctuary had largely been destroyed by the Persians when they sacked and burned Athens in 480 and 479 B.C. For thirty years, the Athenians purposely left the Acropolis in ruins as a memorial to the sacrifice of their homeland in that war. When at Pericles’ urging the assembly decided to rebuild the temples on the Acropolis, it conspicuously turned first not to reconstruction of the olive-tree sanctuary but rather to building the Parthenon. This spectacular new temple was constructed to honor Athena in her capacity as a warrior serving as the divine champion of Athenian military power. Inside the Parthenon was placed a gold-and-ivory statue over thirty feet high portraying the goddess in battle armor and holding in her outstretched hand a six-foot statue of the figure of Victory (nikē in Greek).

Like all Greek temples, the Parthenon was meant as a house for its divinity, not as a gathering place for worshippers. In its general design, the Parthenon was representative of the standard architecture of Greek temples: a rectangular box with doors on a raised platform, a plan that the Greeks probably derived from the stone temples of Egypt. The box was fenced in by columns all around. The columns were carved in the simple style called Doric, in contrast to the more elaborate Ionic or Corinthian styles that have often been imitated in modern buildings (for example, in the Corinthian-style facade of the Supreme Court Building in Washington, DC). Only priests and priestesses could enter the temple, but public religious ceremonies took place around the altar outside its east end.