As mentioned in the previous chapter, the prosperity and cultural achievements of Athens in the mid-fifth century B.C. have led to this period being called a Golden Age in the city-state’s history. The state of the surviving ancient evidence, which consistently comes more from Athens than from other city-states, and the focus of modern popular interest in ancient Greece, which has traditionally remained on the magnificent architectural remains of Athens, have resulted in Greek history of this period being centered almost exclusively on just Athenian history. For these reasons, we really are talking mostly about Athens when we speak of the Golden Age of Greece.

That being said, it seems fair to point out that Athenian prominence in the story of Classical Greece is no accident and reflects the unprecedented changes that characterized the culture and society of Athens in the fifth century B.C. At the same time, central aspects of Athenian life remained unchanged. The result was a mix of innovation and continuity that created tensions that sometimes proved productive and sometimes detrimental. Tragic drama developed as a publicly supported art form performed before mass audiences, which explored troubling ethical issues relevant both to the life of individuals and of the community. Also emerging in the fifth century was a new and—to traditionalists—upsetting form of education for wealthy young men with ambitions in public life. For upper-class women, public life remained constrained by the limitations of modesty and their exclusion from the political affairs that filled the days of many of their husbands. Women of the poorer classes, on the other hand, could have more contact with the public, male world because they had to work and therefore interact with strangers to earn money to help support their families. The interplay of continuity and change created tensions that were tolerable until the pressure of conflict with Sparta in the Peloponnesian War strained Athenian society to the breaking point. All these changes took place against the background of traditional Greek religion, which remained prominent in public and private life because most people never lost their faith that the gods’ will mattered in their lives as citizens and as individuals.

500–323 B.C.: The Greek Classical Age.

458 B.C.: Aeschylus’s trilogy of tragedies, The Oresteia (Agamemnon, The Libation Bearers, The Eumenides), produced at Athens.

c. 450 B.C.: The sophist Protagoras makes his first visit to Athens.

c. 447 B.C.: Sophocles’ tragedy Ajax probably produced at Athens.

444 B.C.: Protagoras makes laws for colony of Athenians and others being sent to Thurii in southern Italy.

c. 441 B.C.: Sophocles’ tragedy Antigone probably produced at Athens.

431 B.C.: Euripides’ tragedy Medea produced at Athens.

As the Ionic frieze on the Parthenon revealed so dramatically, the Athenians in the mid-fifth century B.C. believed they enjoyed the favor of the gods and were willing to spend public money—and lots of it—to erect beautiful and massive monuments in honor of the deities protecting them. This belief corresponded to the basic tenet of Greek religion: Human beings both as communities and as individuals paid honors to the gods to thank them for blessings received and to receive blessings in return. Those honors consisted of public sanctuaries, sacrifices, gifts to the sanctuaries, and festivals of songs, dances, prayers, and processions. A seventh-century B.C. bronze statuette in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, which a man named Mantiklos gave to a sanctuary of Apollo to honor the god, makes clear why individuals gave such gifts. On its legs Mantiklos inscribed his understanding of the transaction: “Mantiklos gave this from his share to the Far Shooter of the Silver Bow [Apollo]; now you, Apollo, do something beneficial for me in return” (BMFA accession number 03.997). This idea of reciprocity between gods and humans defined the Greek understanding of the divine. Gods did not love human beings, except sometimes literally in mythological stories of gods choosing particular favorites or taking earthly lovers and producing half-divine children. Rather, they supported humans who paid them honor and avoided offending them. If human beings angered the gods, the deities could punish the offenders by sending such calamities as famines, earthquake, epidemic disease, or defeat in war. Disaster and vengeance could also be inflicted on people from the action of the natural order of the universe, of which the gods were a part but not necessarily the guarantors. For example, death, including murder, created a state of pollution (miasma). Corpses had to receive purification and proper burial to remove the pollution before life around it could return to normal; murderers had to receive just punishment for their crimes, or the entire community—not just the criminal—would experience dire consequences, such as infertility or the births of monstrous offspring, starvation from bad harvests, and illness and death from epidemic disease.

The greatest religious difficulty for human beings lay in anticipating what specific actions might make a god angry. By definition, mortals could not fully understand the gods: The gap between the mortal and the divine was just too great. A few standards of behavior that people believed the gods demanded of them were codified in a traditional moral order with clear rules to follow. For example, the Greeks believed that the gods demanded hospitality for strangers and proper burial for family members and that the gods punished acts of murder and instances of exceptional or violent arrogance (hybris). Otherwise, when things went wrong in their lives, people consulted oracles, analyzed dreams, conducted divination rituals, and studied the prophecies of seers to seek clues as to what they might have done to anger a divinity. Offenses could be acts such as forgetting a sacrifice, blasphemy (explicitly denying the power of the gods), failing to keep a vow to pay an honor to a particular god, or violating the sanctity of a temple area. The gods were regarded as especially concerned with certain human transgressions that disrespected their divine majesty, such as people breaking agreements that they had sworn to others while invoking the gods as witnesses that they would keep their word. The gods were seen as generally uninterested in common crimes, which humans had to police for themselves.

The Greeks believed their gods lived easy lives, exposed to pain sometimes in their dealings with one another or sometimes sad at the misfortunes of favored humans, but essentially carefree in their immense power and immortality. The twelve most important of the gods, headed by Zeus as king of the gods, were envisioned assembling for banquets atop Mount Olympus, the highest peak in mainland Greece at nearly 10,000 feet. Hera, the wife of Zeus, was queen of the gods; Zeus’s brother Poseidon was god of the sea; Athena was born directly from the head of Zeus as goddess of wisdom and war; Ares was the male god of war; Aphrodite was goddess of love; Apollo was the sun god, while Artemis was the moon goddess; Demeter was goddess of agriculture; Hephaestus was god of fire and technology; Dionysus was god of wine, pleasure, and disorder; Hermes was the messenger of the gods. Hades, god of the underworld, was also a brother of Zeus, but he was not strictly speaking an Olympian deity, because he spent his time under the earth presiding over the world of the dead.

Like the prickly warriors of the stories of Homer, who became enraged at any acts or words of disrespect to their status, the gods were always alert for insults to their honor. “I am well aware that the gods are envious of human success and prone to disrupt our affairs,” is Solon’s summary of their nature in one famous anecdote in which he is portrayed as giving advice to another famous person, in this case Croesus, before the Lydian king lost his kingdom to the Persians (Herodotus, The Histories 1.32).

To show respect for a god, worshippers prayed, sang hymns of praise, offered sacrifices, and presented offerings at the deity’s sanctuary as part of the system of worship and rituals forming the particular god’s cult; each divine being had a separate cult with its specific practices and traditions, and major divinities could have more than one cult. In the sanctuary of a god or goddess, a person could honor and thank the deity for blessings and seek to propitiate him or her when serious troubles, which were understood as indications of divine anger at human behavior, had struck the petitioner. Private individuals offered sacrifices at home with the household gathered around, and often the family’s slaves were allowed to join the gathering. The sacrifices of public cults of gods and goddesses were conducted by priests and priestesses, who were in most cases chosen from the citizen body as a whole but otherwise existed as ordinary citizens. The priests and priestesses of Greek cults were usually attached to a certain sanctuary or shrine and did not seek to influence political or social matters. Their special knowledge consisted of knowing how to perform the gods’ rites in a particular location in accordance with ancestral tradition. They were not guardians of theological orthodoxy, because Greek religion had no systematic theology or canonical dogma; it also lacked any groups or hierarchies comparable to today’s religious leaders and institutions that oversee and enforce correct doctrine.

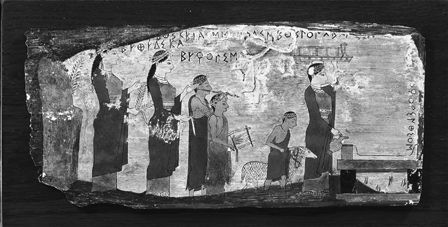

The ritual of sacrifice provided the primary occasion of contact between the gods and their worshippers, symbolizing the reciprocal, if unequal, relations between divine and human beings (fig. 7.1). The great majority of sacrifices took place as regularly scheduled events on the community’s civic calendar. At Athens the first eight days of every month were marked by specified demonstrations of the citizens’ piety toward the deities of the city-state’s official cults. The third day of each month, for example, was celebrated as Athena’s birthday and the sixth as that of Artemis, the goddess of wild animals, who was also the special patroness of the Athenian Council of Five Hundred. Artemis’s brother, Apollo, was honored on the following day. Athens boasted of having the largest number of religious festivals in all of Greece, with nearly half the days of the year featuring one, some large and some small. Not everyone attended all the festivals, and hired laborers’ contracts stated how many days off they received to attend religious ceremonies. Major occasions such as the Panathenaic festival, whose procession probably was portrayed on the Parthenon frieze, attracted large crowds of women and men. The Panathenaic festival honored Athena not only with sacrifices and parades but also with contests in music, dancing, poetry, and athletics. Valuable prizes were awarded to the winners. Some religious rituals were for women only; one famous women-only gathering was the three-day festival for married women in honor of the goddess Demeter, the protector of agriculture and life-giving fertility.

Fig. 7.1: Painting was the favorite form of ancient Greek art, but little has survived. This picture painted in vivid colors on wood shows the preparations, including playing music, for the sacrifice of a sheep to a divinity. Gianni Dagli Orti / The Art Archive at Art Resource, NY.

Despite different cults having many differing rituals, sacrifice served as their centering experience. Sacrifices ranged from the slaughter of large animals to bloodless offerings of fruits, vegetables, and small cakes. It seems possible that the tradition of animal sacrifice had its deepest roots in the lives of prehistoric hunters, for whom such rites might have expressed their uneasiness about the paradox of having to kill other living beings so that they themselves could eat and survive. The Greeks of the Classical Age sacrificed valuable and expensive domesticated animals such as cattle, which their land supported in only small numbers, to express their reverence for the majesty of the gods, to ask for good fortune for themselves and their community, to symbolize their control over the animal world, and to have a rare meal of meat. The sacrifice of a large animal provided an occasion for the community to reassemble to reaffirm its ties to the divine world and, by sharing the roasted meat of the sacrificed beast, for the worshippers to benefit personally from a good relationship with the gods. Looking back on fifth-century B.C. Athens, the orator Lysias explained the tradition—and the necessity—of public sacrifice: “Our ancestors handed down to us the most powerful and prosperous community in Greece by performing the prescribed sacrifices. It is therefore proper for us to offer the same sacrifices as they, if only for the sake of the success which has resulted from those rites” (Orations 30.18).

Procedures for sacrificing animals specified strict rules meant to ensure the purity of the occasion, and the elaborate requirements for conducting a blood sacrifice show how seriously and solemnly the Greeks regarded the sacrificial killing of animals. Sacrifices were performed at altars placed outside in front of temples, where large groups of worshippers could gather; the inside of the building was reserved for the god and the priests. The victim had to be an unblemished domestic animal, specially decorated with garlands and induced to approach the altar as if of its own will. The assembled crowd had to maintain a strict silence to avoid possibly impure remarks. The sacrificer sprinkled water on the victim’s head so it would, in shaking its head in response to the sprinkle, appear to consent to its death. After washing his hands, the sacrificer scattered barley grains on the altar fire and the victim’s head, and then cut a lock of the animal’s hair to throw on the fire. Following a prayer, he swiftly cut the animal’s throat while musicians played flutelike pipes and while female worshippers screamed to express the group’s ritual sorrow at the victim’s death. The carcass was then butchered, with some portions thrown on the altar fire so their aromatic smoke could waft upward to the god of the cult. The rest of the meat was then distributed among the worshippers.

Greek religion included many activities besides those of the cults of the twelve Olympian deities. Families marked important private moments such as birth, marriage, and death with prayers, sacrifices, and rituals. In the fifth century B.C. it became increasingly common for ordinary citizens, not just members of the elite, to make offerings at the tombs of their relatives. Nearly everyone consulted seers about the meanings of dreams and omens and sought out magicians for spells to improve their love lives, or curses to harm their enemies. Particularly important both to the community and to individuals were what we call hero cults, whose rituals were performed at the tomb of a man or woman, usually from the distant past, whose remains were thought to retain special power. Athenian soldiers in the battle of Marathon in 490 B.C., for example, had reported having seen the ghost of the hero Theseus leading the way against the Persians. When Cimon in 475 brought back to Athens bones agreed to be those of Theseus, who was said to have died on a distant island, the people of Athens celebrated the occasion as a major triumph for their community and had the remains installed in a special shrine at the center of the city. The power of a hero’s remains was local, whether for revealing the future through oracles, for healing injuries and disease, or for providing assistance in war. The strongman Heracles (Hercules) was the only Greek hero to whom cults were established internationally, all over the Mediterranean world. His superhuman feats in overcoming monsters and generally doing the impossible gave him an appeal as a protector in many city-states.

International in a different sense was the cult of Demeter and her daughter Korē (or Persephone), whose headquarters were located at Eleusis, a settlement on the west coast of Attica. The central rite of this cult was called the Mysteries, a series of ceremonies of initiation into the secret knowledge of the cult, whose name is derived from the Greek word mystēs (“initiate”). Those initiated into these Eleusinian Mysteries became members of a group with special knowledge unavailable to the uninitiated. All free people who spoke Greek, from anywhere in the world—women and men, adults and children—were eligible for initiation, if they were free of pollution. Some slaves who worked in the sanctuary were also eligible for initiation. The process of becoming an initiate proceeded in several stages. The main rituals took place during an annual festival lasting almost two weeks. This mystery cult became so important that the states of Greece honored an international agreement specifying a period of fifty-five days for guaranteed safe passage through their territories for travelers going to and from the festival. Prospective initiates participated in a complicated set of ceremonies that culminated in the revelation of Demeter’s central secret after a day of fasting. The revelation was performed in an initiation hall constructed solely for this purpose. Under a roof fifty-five yards square supported on a forest of interior columns, the hall held three thousand people standing around its sides on tiered steps. The most eloquent proof of the sanctity attached to the Mysteries of Demeter and Korē is that throughout the thousand years during which the rites were celebrated, we know of no one who ever revealed the secret. To this day, all we know is that it involved something done, something said, and something shown. It is certain, however, that initiates expected to fare better in their lives on earth and—this is highly significant for ancient Greeks’ views of the afterlife—were also promised a better fate after death. “Richly blessed is the mortal who has seen these rites; but whoever is not an initiate and has no share in them, that one never has an equal portion after death, down in the gloomy darkness,” are the words describing the benefits of initiation in a sixth-century B.C. poem from the collection called Homeric Hymns (Hymn to Demeter 480–482).

A similar concern over what awaited human beings after death lay at the heart of other mystery cults, whose sanctuaries were located elsewhere in the Greek world. Most of them were also believed to bestow protection on initiates in their daily lives, whether against ghosts, illness, poverty, shipwrecks, or the countless other mundane dangers of life. This divine protection given worshippers was provided, however, only as a reward for appropriate conduct, not just for an abstract belief in the gods. For the ancient Greeks, gods expected honors and rites, and Greek religion required action and proper behavior from human beings. Greeks had to say prayers and sing hymns honoring the gods, perform sacrifices, support festivals, and undergo purifications. These rites represented an active response to the precarious conditions of human life in a world in which early death from disease, accident, or war was commonplace. Furthermore, the Greeks believed the same gods were responsible for sending both good and bad into the world. As Solon warned Croesus, “In all matters look to the end, and to how it turns out. For many people have enjoyed prosperous happiness as a divine gift, only afterwards to be uprooted utterly” (Herodotus, The Histories 1.32). As a result, the Greeks of the Classical Age had no automatic expectation that they would achieve paradise at some future time when evil forces would finally be vanquished forever through divine love. Their assessment of existence made no allowance for change in the relationship between the human and the divine. That relationship encompassed sorrow as well as joy, punishment in the here and now, with the hope for divine favor both in this life and in an afterlife for initiates of the Eleusinian Mysteries and other similar mystery cults.

The problematic relationship between gods and humans formed the basis of Classical Athens’s most enduring cultural innovation: the tragic dramas performed over three days at the major festival of the god Dionysus held in the late spring every year. These plays, still read and produced on stage today, were presented in ancient Athens as part of a contest for the authors of plays, in keeping with the deeply competitive spirit characteristic of Greek society. Athenian tragedy reached its peak as a dramatic form in the fifth century B.C., as did comedy, the other equally significant type of public drama of Athens (which will be discussed in the next chapter).

Each year, one of Athens’s magistrates chose three authors to present four plays each at the festival of Dionysus. Three were tragedies and one a satyr play, so named from the actors portraying the half-human, half-animal (horse or goat) satyrs who were featured in this theatrical blend of drama and farce. The term tragedy—derived, for reasons now lost, from two Greek words meaning “goat” and “song”—referred to plays with plots involving fierce conflicts and characters representing powerful human and divine forces. Playwrights composed their tragedies in poetry with elevated, solemn language and frequently based their stories on imaginative reinterpretations of the violent consequences of the interaction between gods and people. The play often ended with a resolution to the trouble—but only after terrible suffering, emotional turmoil, and traumatic deaths.

The performance of ancient Greek plays bore little resemblance to conventional modern theater productions. Dramas were produced during the daytime in outdoor theaters (fig. 7.2). At Athens, the theater was located on the slope of the southern hillside of Athens’s Acropolis. This theater sacred to Dionysus held around fourteen thousand spectators overlooking an open circular area in front of a slightly raised stage platform. Seating was temporary in the fifth century B.C.; the first stone theater was not installed until the following century. To ensure fairness in the competition, all tragedies were required to have the same-size cast, all of whom were men: three actors to play the speaking roles of all male and female characters, and fifteen chorus members, who performed songs and dances in the circular area in front of the stage, called the orchestra. The chorus had a leader who periodically engaged in dialogue with the other characters in the play. Since all the actors’ lines were in verse with special rhythms, the musical aspect of the chorus’s role was an elaboration of the overall poetic nature of Athenian tragedy and the dancing was part of its strongly visual impact on spectators.

Even though scenery on the stage was sparse, a well-written and produced tragedy presented a vivid spectacle to its huge outdoor audience. The chorus wore elaborate decorative costumes and trained for months to perform intricate dance routines. The actors, who wore masks, used broad gestures to be seen as far away as the last row of seats and could project their voices with force, to be understood over wind blowing through the outdoor auditorium and over the crowd noise that inevitably arose from such large audiences; this incidental audio interference could overwhelm the good acoustics of the carefully built theaters in major city-states. A good voice and precise enunciation were crucial to a tragic actor because words represented the heart of a tragedy, in which dialogue and long speeches were more significant for conveying meaning than physical action. Special effects were, however, part of the spectacle. For example, a crane allowed actors playing the roles of gods to fly suddenly onto the stage, like superheroes in a modern movie. The actors playing the lead roles, called the protagonists (“first competitors”), were also competing against each other for the designation of best actor. So important was it to have a first-rate lead actor to be able to put on a successful tragedy in the authors’ competition that protagonists were assigned by lot to the competing playwrights of the year to give all three of them an equal chance to have the finest cast. Great protagonists became enormously popular figures, although, unlike many authors of plays, they were not usually members of the social elite.

Fig. 7.2: The prosperity stemming from its internationally famous sanctuary of the healing god Asclepius allowed the city-state of Epidaurus in the Peloponnese to build a theater in the fourth century B.C. for fifteen thousand spectators to view plays and festival performances. Its acoustics are famous: A word softly spoken on its stage in quiet conditions can be heard in the top row of seats. Wikimedia Commons.

The author of a slate of tragedies in the festival of Dionysus also served as director, producer, musical composer, choreographer, and sometimes even one of the actors. Only men with private wealth could afford the endless amounts of time such work demanded, because the prizes in the tragedy competition were probably modest and intense rehearsals lasted for months before the festival. As citizens, playwrights also fulfilled the normal military and political obligations of an Athenian man. The best-known Athenian tragedians—Aeschylus (525–456 B.C.), Sophocles (c. 496–406 B.C.), and Euripides (c. 485–406 B.C.)—all served in the army, held public office at some point in their careers, or did both. Aeschylus fought at Marathon and Salamis; the epitaph on his tombstone, which says nothing of his great success as a dramatist, reveals how highly he valued his contribution to his city-state as a citizen-soldier: “Under this stone lies Aeschylus the Athenian, son of Euphorion. . . . The grove at Marathon and the Persians who landed there were witnesses to his courage” (Pausanias, Guide to Greece 1.14.5).

Aeschylus’s pride in his military service to his homeland points to a fundamental characteristic of Athenian tragedy: It was a public art form, an expression of the polis that explored the ethical dilemmas of human beings caught in conflict with the gods and with one another in a polis-like community. The plots of most tragedies were based on stories set in ancient times, before the creation of the polis, when myth said that kings ruled in Greece; tales from the era of the Trojan War were very popular subjects. Nevertheless, the moral issues embedded in the playwrights’ reinterpretations of these old legends always pertained to the society and obligations of citizens in the contemporary polis. For example, Sophocles presented, probably in 447, a play entitled Ajax, the name of the second-best warrior (Achilles had been number one) in the Greek army fighting the Trojans. When the other fighters encamped before Troy voted to award the armor of the now-dead Achilles to the clever and glib Odysseus rather than to the physically more-imposing but mentally less-sharp Ajax, losing this competition of honor drove Ajax to madness and set him on a berserk rampage against his former friends in the Greek army. The goddess Athena thwarted Ajax because he had once arrogantly rejected her help in battle. Disgraced by his failure to secure revenge, Ajax committed suicide despite the pleas of his wife, Tecmessa, not to abandon his family to the tender mercies of his enemies. Odysseus then used his verbal skills to convince the hostile Greek chiefs to bury Ajax because the future security of the army and the obligations of friendship demanded that they obey the divine injunction always to bury the dead, regardless of how badly the person had behaved while living. Odysseus’s arguments in favor of burying Ajax anachronistically treat the army as if it were a polis, and his use of persuasive speech to achieve accommodation of conflicting individual interests to the benefit of the community corresponds to the way in which disputes in fifth-century Athens were supposed to be resolved.

In Antigone (probably produced in 441 B.C.), Sophocles presented a drama of bitter conflict between the family’s moral obligation to bury its dead in obedience to divine command and the male-dominated city-state’s need to preserve order and defend its communal values. Antigone, the daughter of Oedipus, the now-deceased former king of Thebes, comes into conflict with her uncle, the new ruler Creon, when he prohibits the burial of one of Antigone’s two brothers on the grounds that he was a traitor. This brother had attacked Thebes after the other brother had broken an agreement to share the kingship. Both brothers died in the ensuing battle, but Antigone’s uncle allowed the burial only of the brother who had remained in power at Thebes. When Antigone defies her uncle by symbolically burying the allegedly traitorous brother, her uncle the ruler condemns her to die. He realizes his error only when religious sacrifices go spectacularly wrong, indicating that the gods have rejected his decision and were expressing their anger at his outrage against the ancient tradition requiring proper burial of everyone. Creon’s decision to punish Antigone ends in personal disaster when his son, who was in love with Antigone, kills himself, and then his wife, distraught at the loss of their son, commits suicide. In this horrifying story of anger, pride, and death, Sophocles deliberately exposes the right and wrong on each side of the conflict. Although Antigone’s uncle eventually acknowledges a leader’s responsibility to listen to his people, the play offers no easy resolution of the competing interests of divinely sanctioned moral tradition upheld by a woman and the political rules of the state enforced by a man.

A striking aspect of Greek tragedies is that these plays written and performed by men frequently portray women as central, active figures in their plots. At one level, the frequent depiction of women in tragedy allowed men accustomed to spending most of their time with other men to peer into what they imagined the world of women must be like. But the heroines portrayed in fifth-century Athenian tragedies also served to explore the tensions inherent in the moral code of contemporary society by strongly reacting to men’s violations of that code, especially as it pertained to the family and their status and honor as women. Sophocles’ Antigone, for example, confronts the male ruler of her city because he deprived her family of its traditional prerogative to bury its dead. Antigone is remarkable in fearlessly criticizing a powerful man in a public debate about right and wrong. Sophocles, in other words, shows a woman who can express herself with the freedom of speech of an Athenian male citizen, who believed that he had the right to say things publicly that he knew other people did not want to hear and that would even enrage them. In this way and many others, heroines such as Antigone display through their actions and words on stage as characters in tragedies the qualities of courage and fortitude that men strove to achieve in their daily lives as politically engaged citizens.

Another heroine of tragedy equal to any man in resolve and action was Clytemnestra, the wife of Agamemnon, the leader of the Greek army in the Trojan War, in the drama Agamemnon by Aeschylus (produced in 458 B.C.). In the story as told in this play, Clytemnestra takes a lover and rules her city in her husband’s place when Agamemnon subverts his marriage by sacrificing their daughter to appease an angry goddess who is holding up the Greek army sailing against Troy. Agamemnon then stays away from home for ten years during the war, and finally brings back home with him a captive Trojan princess whom he intends to install as a concubine alongside his legitimate spouse in their house. Enraged by her husband’s betrayal of her and his public disrespect for her status as wife, mother, and queen, Clytemnestra arranges the murder of Agamemnon, avenging her honor but also motivating her children to seek deathly revenge on her and her lover for the slaughter of their father.

Of the three best-known authors of Athenian tragedies, Euripides depicts the most sensational heroines. His heroine Medea, the main character in the play Medea produced in 431 B.C., reacts with a shattering violence when Jason, her husband, proposes to divorce her in order to marry a richer, more-prominent woman. Jason’s plans flout the social code governing marriage: A husband had no moral right to divorce a wife who had fulfilled her primary duty by bearing legitimate children, especially sons. To gain revenge, Medea uses magic to kill their children and Jason’s new bride. Medea’s murder of her own offspring destroys her proper role as wife and mother, yet she argues forcefully for a reevaluation of that role. She insists that women who bear children are due respect at least commensurate with that granted men who fight as hoplites: “People say that we women lead a safe life at home, while men have to go to war. What fools they are! I would much rather fight in the phalanx three times than give birth to a child only once” (Medea, lines 248–251).

Despite their often-gloomy outcomes, Sophocles’ plays were overwhelmingly popular, and he earned the reputation as the Athenians’ favorite author of tragedies. In a sixty-year career as a playwright, he competed in the dramatic festival about thirty times, winning at least twenty times and never finishing with less than second prize. Since the winning plays were selected by a panel of ordinary male citizens who were apparently influenced by the audience’s reaction, Sophocles’ record clearly means his works appealed to the large number of citizens attending the drama competition of the festival of Dionysus. These audiences most likely included women as well as men, and the issues raised by the plays certainly gave prominence to gender relations both in the family and in the community. We cannot know the spectators’ precise understanding of Sophocles’ messages and those of other authors’ tragedies, but the audience must have been aware that the central characters of the plays were figures who fell from positions of power and prestige into violent disasters. These awful reversals of fortune come about not because the characters are absolute villains but because, as human beings, they are susceptible to a lethal mixture of error, ignorance, and hubris that the gods punish.

The Athenian Empire was at its height when audiences at Athens were seeing the plays of Sophocles. The presentation of the plays at the festival of Dionysus was preceded by a procession in the theater to display the revenues of Athens received from the dues paid by the allies in the Delian League. All the Athenian men in the audience were actual or potential combat veterans in the citizen-militia of the city-state and thus personally acquainted with the possibility of having to endure or inflict deadly violence in the service of their community. Thoughtful spectators would have perhaps reflected on the possibility that Athens’s current power and prestige, managed as it was by human beings in the democratic assembly, remained hostage to the same forces that the playwrights taught controlled the often-bloody fates of the heroes and heroines of tragedy. Tragedies certainly had appeal because they were engrossing purely as entertainment, but they also had an educative function: to remind citizens, especially those who cast votes to make policy for the polis, that success and the force needed to maintain it engendered problems of a moral complexity too formidable to be fathomed casually or arrogantly.

Athenian women earned status and acquired power in both private and public life through their central roles in the family and religion, respectively. Their formal absence from politics, however, meant that their contributions to the city-state might be overlooked by men. Melanippe, another heroine in a tragedy by Euripides, vigorously expresses this judgment in a famous speech denouncing men who denigrate women, expressing sentiments that have a modern echo: “Empty is the slanderous blame men place on women; it is no more than the twanging of a bowstring without an arrow; women are better than men, and I will prove it: women make agreements without having to have witnesses to guarantee their honesty. . . . Women manage the household and preserve its valuable property. Without a wife, no household is clean or happily prosperous. And in matters pertaining to the gods—this is our most important contribution—we have the greatest share. In the oracle at Delphi we propound the will of Apollo, and at the oracle of Zeus at Dodona we reveal the will of Zeus to any Greek who wishes to know it. Men cannot rightly perform the sacred rites for the Fates and the Anonymous Goddesses, but women make them flourish. . . .” (Melanippe the Captive, Fragment 13a).

Greek drama sometimes emphasized the areas in which Athenian women most obviously and publicly contributed to the polis: by acting as priestesses, by bearing and raising legitimate children to be the future citizens of the city-state, and by serving as managers of their households’ property. Women’s property rights in Classical Age Athens reflected both the importance of the control of property by women and the Greek predisposition to promote the formation and preservation of households headed by property-owning men. Under Athenian democracy, women could control property, even land—the most valued possession in their society—through dowry and inheritance, although they faced more legal restrictions than men did when they wanted to sell their property or give it away as gifts. Like men, women were supposed to preserve their property to be handed down to their children. If a family had any living sons, then daughters did not inherit from their father’s property, instead receiving a portion of the family’s wealth in their dowries at marriage. Similarly, a son whose father was still alive at the time of the son’s marriage might receive a share of his inheritance ahead of time to allow him to set up a household. Perhaps one household in five had only daughters living, in which case the father’s property then passed by inheritance to the daughters. Women could also inherit from other male relatives without male children. A bride’s husband had legal control over the property in his wife’s dowry, and their respective holdings frequently became commingled. In this sense husband and wife were co-owners of the household’s common property, which had to be formally allotted between its separate owners only if the marriage were dissolved. The husband was legally responsible for preserving the dowry and using it for the support and comfort of his wife and any children she bore him, and a groom often had to put up valuable land of his own as collateral to guarantee the safety of his bride’s dowry. Upon her death, the dowry became the inheritance of her children. The expectation that a woman would have a dowry tended to encourage marriage within groups of similar wealth and status. As with the rules governing women’s rights to inheritances, customary dowry arrangements supported the society’s goal of enabling males to establish and maintain households—because daughters’ dowries were usually smaller in value than their brothers’ inheritances—and therefore kept the bulk of a father’s property attached to his sons.

The same goal shows up clearly in Athenian law concerning heiresses. If a father died leaving only a daughter to survive him, his property passed to her as his heiress, but she did not own it in the modern sense of being able to dispose of it as she pleased. Instead, Athenian law (in the simplest case) required her father’s closest male relative—her official guardian after her father’s death—to marry her himself, with the aim of producing a son. The inherited property then belonged to that son when he reached adulthood. As a disputant in a fourth-century B.C. court case about an heiress said, “We think that the closest kin should marry her and that the property should belong to the heiress until she has sons, who will take it over two years after coming of age” (Isaeus, Orations, Fragment 25).

The law on heiresses served to keep the property in their fathers’ families, and, theoretically at least, it could require major personal sacrifices from the heiress and her closest living male relative. That is because the law applied regardless of whether the heiress was already married (so long as she had not given birth to any sons) or whether the male relative already had a wife. The heiress and the male relative were both supposed to divorce their present spouses and marry each other, which they might well not be at all willing to do. In practice, therefore, people often found ways to get around this requirement by various technical legal maneuvers. In any case, the law was intended to prevent rich men from getting richer by bribing wealthy heiresses’ guardians to marry the woman and therefore merge their estates, and, above all, to stop property from piling up in the hands of unmarried women. At Sparta, Aristotle reported, precisely this agglomeration of wealth outside men’s control took place as women inherited land or received it in their dowries without—to Aristotle’s way of thinking—adequate regulations requiring the women to remarry. He claimed that women in this way had come to own 40 percent of Spartan territory. The law at Athens was evidently more successful at regulating women’s control over property in the interests of promoting the formation of households headed by property-owning men.

In Euripides’ play bearing her name, Medea’s comment to the effect that men said women led a safe life at home reflected the expectation in Athenian society that a woman from the propertied class would avoid frequent or close contact with men who were not members of her own family or its circle of friends. Women of this socioeconomic level were therefore supposed to spend much of their time in their own homes or in the homes of women friends. There, women dressed, slept, and worked in interior rooms and in the central open courtyard characteristic of Greek houses. Male visitors from outside the family were banned from entering the rooms in a house designated as women’s space, which did not mean an area to which women were confined but rather the places where they conducted their activities in a flexible use of domestic space varying from house to house. In the rooms women controlled, they would spin wool for clothing while chatting with female friends over for a visit, play with their children, and direct the work of female slaves. In the courtyard at the center of the house, where men and women could interact, they would offer their opinions on family matters and pubic politics to male family members as they came and went. One room in a house was usually set aside as the men’s dining room (andrōn), where the husband could entertain male friends, reclining on couches set against the wall in Greek fashion, without their coming into contact with the women of his family except for slaves. Poor women had much less time for domestic activities, because they, like their husbands, sons, and brothers, had to leave their homes—often only a crowded rental apartment—to find work. As small-scale entrepreneurs, they set up stalls to sell bread, vegetables, simple clothing, or trinkets. Their male relatives had more freedom to work in a variety of jobs, especially as laborers in workshops, foundries, and construction sites.

Expectations of female modesty dictated that a woman with servants who answered the door of her house herself would be reproached as careless of her reputation. So too a proper woman went out only for an appropriate reason, usually covering her head with a scarflike veil. Fortunately, Athenian life offered many occasions for women to go out in the city: religious festivals, funerals, childbirths at the houses of relatives and friends, and trips to workshops to buy shoes or other articles. Sometimes a woman’s husband would escort her, but more often she was accompanied only by a servant or female friends and had more opportunity for independent action. Social protocol demanded that men not speak the names of respectable women in public conversations and speeches in court unless practical necessity demanded it.

Since women stayed inside or in the shade so much, those rich enough not to have to work maintained very pale complexions. This pallor was much admired as a sign of an enviable life of leisure and wealth, much as an even, all-over tan is valued today for the same reason. Women regularly used powdered white lead as makeup to give themselves a suitably pallid look. Presumably, many upper-class women valued their life of limited contact with men outside the household as a badge of their superior social status. In a gender-divided society such as that of the wealthy at Athens, the primary opportunities for personal relationships in an upper-class woman’s life probably came in her contact with her children and the other women with whom she spent most of her time.

The social restrictions on women’s freedom of movement served men’s goal of avoiding uncertainty about the paternity of children by limiting opportunities for adultery among wives and protecting the virginity of daughters. Given the importance of citizenship as the defining political structure of the city-state and of a man’s personal freedom, an Athenian husband, like other Greeks and indeed everyone else, felt it crucially important to be certain a boy truly was his son and not the offspring of some other man, who could conceivably even be a foreigner or a slave. Furthermore, the preference for keeping property in the father’s line meant that the boys who inherited a father’s property needed to be his legitimate sons. In this patriarchal system, citizenship and property rights therefore led to restrictions on women’s freedom of movement in society. Women who did bear legitimate children, however, immediately earned a higher status and greater freedom in the family, as explained, for example, by an Athenian man in his remarks before a jury when he was on trial for having killed an adulterer whom he had caught with his wife: “After my marriage, I initially refrained from bothering my wife very much, but neither did I allow her too much independence. I kept an eye on her. . . . But after she had a baby, I started to trust her more and put her in charge of all my things, believing we now had the closest of relationships” (Lysias, Orations 1.6). Bearing male children brought special honor to a woman because sons meant security for parents. Adult sons could appear in court in support of their parents in lawsuits and protect them in the streets of the city, which for most of its history had no regular police force. By law, sons were required to support their parents in old age, a necessity in a society with no state-sponsored system for the support of the elderly, such as Social Security in the United States. So intense was the pressure to produce sons that stories were common of barren women who smuggled in babies born to slaves to pass them off as their own. Such tales, whose truth is hard to gauge, were credible only because husbands customarily stayed away at childbirth.

Men, unlike women, had sexual opportunities outside marriage that carried no penalties. “Certainly you don’t think men beget children out of sexual desire?” wrote the upper-class author Xenophon. “The streets and the brothels are swarming with ways to take care of that” (Memorabilia 2.2.4). Besides having sex with female slaves, who could not refuse their masters, men could choose among various classes of prostitutes, depending on how much money they had to spend. A man could not keep a prostitute in the same house as his wife without causing trouble, but otherwise he incurred no disgrace by paying for sex. The most expensive female prostitutes the Greeks called “companions” (hetairai). Usually from another city-state than the one in which they worked, companions supplemented their physical attractiveness with the ability to sing and play musical instruments at men’s dinner parties, to which wives were not invited (fig. 7.3). Many companions lived precarious lives, subject to exploitation or even violence at the hands of their male customers. The most accomplished companions, however, could attract lovers from the highest levels of society and become sufficiently rich to live in luxury on their own. Their independent existence and earned income strongly distinguished them from well-off married women, as did the freedom to control their own sexuality. Equally distinctive was their cultivated ability to converse with men in public. Like the geisha of Japan, companions in ancient Greece entertained men especially with their witty, bantering conversation. Their characteristic skill at clever taunts and verbal snubs endowed companions with a power of speech ordinarily denied to most proper women. Only very rich citizen women of advanced years, such as Elpinike, the sister of the famous military commander Cimon, could enjoy a similar freedom of expression. She, for example, once publicly rebuked the political leader Pericles for having boasted about the Athenian conquest of the city-state on Samos after its rebellion. When other Athenian women were praising Pericles for his success, Elpinike sarcastically remarked, “This really is wonderful, Pericles, . . . that you have caused the loss of many good citizens, not in battle against Phoenicians or Persians, like my brother Cimon, but in suppressing an allied city of fellow Greeks” (Plutarch, Pericles 28).

A man speaking in a lawsuit succinctly described the theoretical purposes assigned the different categories of women by Athenian men: “We have ‘companions’ for the sake of pleasure, ordinary prostitutes for daily attention to our physical needs, and wives to bear legitimate children and to be faithful guards inside our households” (Demosthenes, Orations 59.122). In practice, of course, the roles filled by women did not necessarily correspond to this idealized scheme; a husband could expect his wife to perform all of them. The social marginality of companions—they were often not citizens; they could not legally marry; they had unsavory reputations—empowered them in speech and in sexuality because by definition they were expected to break the norms of respectability. Other women, by contrast, earned respect and social status by obeying these norms.

Fig. 7.3: This red-figure style vase depicts a symposium (men’s drinking party) at which a female “companion” (hetaira) is entertaining the guests by playing music on the aulos, a reed instrument with finger holes. Two of the men are playing kottabos, a messy party game in which they flung the dregs of their wine from their shallow drinking cups. Marie-Lan Nguyen / Wikimedia Commons.

Athenians learned the norms of respectable behavior for both women and men not in school but in their families and from the countless social interactions of everyday life. Formal education in the modern sense hardly existed because schools subsidized by the state did not exist. Only well-to-do families could afford to pay the fees charged by private teachers, to whom they sent their sons to learn to read, to write, perhaps to learn to sing or play a musical instrument, and to train for athletics and military service. Physical fitness was considered so important for men, who could be called on for military service in the militia from the age of eighteen until sixty, that the city-state provided open-air exercise facilities for daily workouts. These gymnasia were also favorite places for political conversations and the exchange of news. The daughters of well-to-do families often learned to read, write, and do simple arithmetic, presumably from being instructed at home, because a woman with these skills would be better prepared to manage the household finances and supplies for the husband of property whom she was expected to marry and partner with in overseeing their resources.

Poorer girls and boys learned a trade and perhaps some rudiments of literacy by helping their parents in their daily work, or, if they were fortunate, by being apprenticed to skilled crafts producers. As mentioned earlier, a law of Solon required fathers to teach their sons a skill for making a living; otherwise, the children would be freed from the duty of supporting their parents when as senior citizens they became too old to work themselves. The level of literacy in Athenian society outside the ranks of the prosperous was probably quite low by modern standards, with only a small minority of the poor able to do much more than perhaps sign their names. The inability to read presented few insurmountable difficulties for most people, who could find someone to read aloud to them any written texts they needed to understand. The predominance of oral rather than written communication meant that people were accustomed to absorbing information by ear (those who could read usually read out loud), and Greeks were very fond of songs, speeches, narrated stories, and lively conversation, and their memories were trained to recall what they heard by ear. Like the son of the famous Athenian general Nicias, people were known to memorize the entire Iliad and Odyssey, for example.

Young men from prosperous families traditionally acquired the advanced skills required for successful participation in the public life of Athenian democracy by observing their fathers, uncles, and other older men as they participated in the assembly, served on the council or as magistrates, and made speeches in court cases. The most important skill to acquire was the ability to speak persuasively in public. In many cases, an older man would choose an adolescent boy as his special favorite to educate. The boy would learn about public life by spending his time in the company of the older man and his adult friends. During the day, the boy would observe his mentor talking politics in the agora or giving speeches in the assembly or courts, help him perform his duties in public office, and work out with him in a gymnasium. Their evenings would be spent at a symposium, a drinking party for men and companions, which could encompass a range of behavior from serious political and philosophical discussion to riotous partying.

Such a mentor-protégé relationship commonly implied homosexual love as an expression of the bond between the boy and the older male, who would normally be married. As mentioned in the discussion of Sparta, it is difficult to apply modern categories and judgments to ancient Greek sexuality and sexual norms; contemporary judgments range from acceptance to condemnation and imputations of pederasty. In any case, Greeks by this period found it natural for an older man to be excited by the physical beauty of a boy (as also of a lovely girl). The love between the older “lover” (erastēs) and the younger “beloved” (erōmenos) implied more than just desire, however. The eroticism of the relationship had to be played out as a type of contest for status, with the younger man wishing to appear desirable but sufficiently in control to reject or modify his older pursuer’s demands, and the older man wishing to demonstrate his power and ability to overcome resistance by winning a physical relationship with the young object of his pursuit. Although male homosexuality outside a mentor-protégé relationship and female homosexuality in general incurred disgrace, the special homosexuality between older mentors and younger protégés was accepted as appropriate behavior in many—but not all—city-states, so long as the older man did not exploit his younger companion purely for physical gratification or neglect the youth’s education in public affairs. Plato portrayed a plain-thinking fifth-century B.C. Athenian man summing up what was apparently a common opinion about appropriate male homosexual love: “I believe that the greatest good for a youth is to have a worthy lover from early on and, for a lover, to have a worthy beloved. The values that men need who want to live lives of excellence lifelong are better instilled by love than by their relatives or offices or wealth or anything else. . . . I mean the values that produce feelings of shame for disgraceful actions and ambition for excellence. Without these values neither a city-state nor a private person can accomplish great and excellent things. . . . Even a small army of such men, fighting side by side, could defeat, so to speak, the entire world because a lover could more easily endure everyone else rather than his beloved seeing him desert his post or throw down his weapons. He would die many times over before allowing that to happen” (Symposium 178c–179a).

In the second half of the fifth century, a new brand of self-proclaimed teachers appeared, offering more organized instruction to young men seeking to develop the skills in public speaking and argumentation needed to excel in democratic politics. These instructors were called sophists (“wise men”), a label that acquired a pejorative sense (preserved in the English word sophistry) because they were so clever at public speaking and philosophic debates. Sophists were detested and even feared by many traditionally minded men, whose political opinions and influence they threatened. The earliest sophists arose in parts of the Greek world other than Athens, but from about 450 B.C. on they began to travel to Athens, which was then at the height of its material prosperity and cultural reputation, to search for pupils who could pay the hefty prices the sophists charged for their instruction. Wealthy young men flocked to the dazzling demonstrations that these itinerant teachers put on to showcase their ability to speak persuasively, an ability that they claimed to be able to impart to students. The sophists were offering just what every ambitious young man wanted to learn, because the greatest single skill that a man in democratic Athens could possess was to be able to persuade his fellow citizens in the debates of the assembly and the council or in lawsuits before large juries. For those unwilling or unable to master the new rhetorical skills of sophistry, the sophists (for stiff fees) would compose speeches to be delivered by the purchaser as his own composition. The overwhelming importance of persuasive speech in an oral culture like that of ancient Greece made the sophists frightening figures to many, for the new teachers offered an escalation of the power of speech that seemed potentially destabilizing to political and social traditions.

The most famous sophist was Protagoras, a contemporary of Pericles, from Abdera in northern Greece. Protagoras moved to Athens around 450 B.C., when he was about forty, and spent most of his career there. His oratorical ability and his upright character so impressed the men of Athens that they chose him to devise a code of laws for a new Panhellenic colony founded in Thurii in southern Italy in 444. Some of Protagoras’s ideas, however, shocked traditional-minded citizens, who feared their effects on the community. One was his agnostic opinion concerning the gods: “Whether the gods exist I cannot discover, nor what their form is like, for there are many impediments to knowledge, [such as] the obscurity of the subject and the brevity of human life” (Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers 9.51 = D.-K. 80B4). It is easy to see how people might think that the gods would take offense at this view and therefore punish the city-state that permitted Protagoras to teach there.

Equally controversial was Protagoras’s denial of an absolute standard of truth, his assertion that every issue has two, irreconcilable sides. For example, if one person feeling a breeze thinks it is warm, while a different person judges the same wind to be cool, Protagoras said there is no way to decide which judgment is correct because the wind simply is warm to the one person and cool to the other. Protagoras summed up his subjectivism (the belief that there is no absolute reality behind and independent of appearances) in the much-quoted opening of his work entitled Truth (most of which is now lost): “Man is the measure of all things, of the things that are that they are, and of the things that are not that they are not” (Plato, Theatetus 151e = D.-K. 80B1). “Man” in this passage (anthrōpos in Greek, hence our word anthropology) seems to refer to the individual human being, both male and female, whom Protagoras makes the sole judge of his or her own impressions. Protagoras’s critics denounced him for these views, accusing him of teaching his students how to make the weaker argument the stronger and therefore how to deceive and bamboozle other people with seductively persuasive but dangerous arguments. This, they feared, was a threat to their democracy, which depended on persuasion based on truth and employed for the good of the community.

The ideas and techniques of argumentation that sophists such as Protagoras taught made many Athenians nervous or even outraged, especially because leading citizens such as Pericles flocked to hear this new kind of teacher. Two related views taught by sophists aroused special controversy: (1) that human institutions and values were not products of nature (physis) but rather only the artifacts of custom, convention, or law (nomos), and (2) that, since truth was relative, speakers should be able to argue either side of a question with equal persuasiveness. The first idea implied that traditional human institutions were arbitrary rather than grounded in immutable nature, and the second idea made rhetoric into an amoral technique for persuasion. The combination of the two ideas seemed exceptionally dangerous to a society so devoted to the spoken word, because it threatened the shared public values of the polis with unpredictable changes. Protagoras himself insisted that his intellectual doctrines and his techniques for effective public speaking were not hostile to democracy, especially because he argued that every person had an innate capability for excellence and that human survival depended on people respecting the rule of law based on a sense of justice. Members of the community, he argued, should be persuaded to obey the laws not because they were based on absolute truth, which did not exist, but because it was in people’s own interests to live according to society’s agreed-upon standards of behavior. A thief, for instance, who might claim that in his opinion a law against stealing had no value or validity, would have to be persuaded that laws against theft worked to his advantage because they protected his own property and promoted the well-being of the community in which he, like everyone else, had to live in order to survive and flourish.

The instruction that Protagoras offered struck some Athenian men as ridiculous hair splitting. One of Pericles’ sons, for example, who had become estranged from his father, made fun of him for disputing with Protagoras about the accidental death of a spectator killed by a javelin thrown by an athlete in a competition. The politician and the sophist had spent an entire day debating whether the javelin itself, the athlete, or the judges of the contest were responsible for the tragic death. Such criticism missed the point of Protagoras’s teachings, however. He never meant to help wealthy young men undermine the social stability of the traditional city-state. Some later sophists, however, had fewer scruples about the uses to which their instruction in arguing both sides of a case might be put. An anonymous handbook compiled in the late fifth century B.C., for example, provided examples of how rhetoric could be used to stand common-sense arguments on their heads:

Greeks interested in philosophy propose double arguments about the good and the bad. Some of them claim that the good is one thing and the bad something else, but others claim that the good and the bad are the same thing. This second group also says that the identical thing might be good for some people but bad for others, or at a certain time good and at another time bad for the same individual. I myself agree with those holding the latter opinion, which I shall investigate by taking human life as my example and its concern for food, drink, and sexual pleasures: these things are bad for a man if he is ill but good if he is healthy and has need of them. Furthermore, overindulgence in these things is bad for the person who gets too much of them but good for those who profit by selling these things to those who overindulge. Here is another point: illness is a bad thing for the patient but good for the doctors. And death is bad for those who die but good for the undertakers and sellers of grave monuments. . . . Shipwrecks are bad for the ship-owners but good for the shipbuilders. When tools become blunt and worn down it is bad for their owners but good for the toolmaker. And if a piece of pottery gets broken, this is bad for everyone else but good for the pottery maker. When shoes wear out and fall apart it is bad for others but good for the shoemaker. . . . In the stadion race for runners, victory is good for the winner but bad for the losers.

—(Dissoi, Logoi [Double Arguments] 1.1–6)

Skill in arguing both sides of a case and a relativistic approach to such fundamental issues as the moral basis of the rule of law in society were not the only aspects of these new intellectual developments that disturbed many Athenian men. Fifth-century B.C. thinkers and philosophers, such as Anaxagoras of Clazomenae in Ionia and Leucippus of Miletus, propounded unsettling new theories about the nature of the cosmos in response to the provocative physics of the earlier Ionian thinkers of the sixth century. Anaxagoras’s general theory postulating an abstract force that he called “mind” as the organizing principle of the universe probably impressed most people as too obscure to worry about, but the details of his thought could offend those who held to the assumptions of traditional religion. For example, he argued that the sun was in truth nothing more than a lump of flaming rock, not a divine entity. Leucippus, whose doctrines were made famous by his pupil Democritus of Abdera, invented an atomic theory of matter to explain how change was possible and indeed constant. Everything, he argued, consisted of tiny, invisible particles in eternal motion. Their endless collisions caused them to combine and recombine in an infinite variety of forms. This physical explanation of the source of change, like Anaxagoras’s analysis of the nature of the sun, seemed to deny the validity of the entire superstructure of traditional religion, which explained events as the outcome of divine forces and the will of the gods.

Many Athenians feared that the teachings of the sophists and philosophers could offend the gods and therefore destroy the divine favor and protection that they believed their city-state enjoyed. Just like a murderer, a teacher spouting doctrines offensive to the gods could bring pollution and therefore divine punishment on the whole community. So deeply felt was this anxiety that Pericles’ friendship with Protagoras, Anaxagoras, and other controversial intellectuals gave his rivals a weapon to use against him when political tensions came to a head in the 430s B.C. as a result of the threat of war with Sparta: His opponents criticized him as being sympathetic to dangerous new ideas as well as to being autocratic in his leadership.

Sophists were not the only thinkers to emerge with new ideas in the mid-fifth century B.C. In historical writing, for example, Hecataeus of Miletus, born in the later sixth century, had earlier opened the way to a broader and more critical vision of the past. He wrote both an extensive guidebook to illustrate his map of the world as he knew it and a treatise criticizing mythological traditions. The Greek historians writing immediately after him concentrated on the histories of their local areas and wrote in a spare, chroniclelike style that made history into little more than a list of events and geographical facts. As mentioned in chapter 1, Herodotus, who was from Halicarnassus (c. 485–425 B.C.), opened an entirely new perspective on the possibilities for history writing by composing his enormous, wide-ranging, and provocative work The Histories. His narrative broke new ground with its vast geographical scope, critical approach to historical evidence, complex interpretation of the innately just nature of the cosmos, and respectful exploration of the culture and ideas of diverse peoples, both Greek and barbarian. To describe and explain the clash between East and West that exploded in the Persian Wars, Herodotus searched for the origins of the conflict both by delving deep into the past and by examining the traditions and assumptions of all the peoples involved. With his interest in ethnography, he recognized the importance and the delight of studying the cultures of others as a component of historical investigation. His subtle examination of what he saw as the evidence for the retributive justice imposed by the natural order of the universe expressed a profound and sometimes disturbing analysis of the fate of human beings on this earth.

Just as revolutionary as the ideas of Herodotus in history were those in medicine by Hippocrates, a younger contemporary whose name became the famous one in the long history of ancient Greek medical theories and treatments. Details are sketchy about the life and thought of this influential doctor from the Aegean island of Cos, but the works preserved under his name show that he took innovative and influential strides toward putting medical diagnosis and treatment on a scientific basis. Hippocrates’ contribution to medicine is remembered today in the oath bearing his name, which doctors customarily swear at the beginning of their professional careers. Earlier Greek medical ideas and treatments had depended on magic and ritual. Hippocrates took a completely new approach, regarding the human body as an organism whose parts must be seen as part of an interrelated whole and whose functioning and malfunctioning must be understood as responses to physical causes. Even in antiquity, however, medical writers disagreed about the underlying theoretical foundation of Hippocrates’ medicine. Some attributed to him the view, popular in later times, that four fluids, called humors, make up the human body: blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile. Being healthy meant being in “good humor.” This intellectual system corresponded to the division of the inanimate world into the four elements of earth, air, fire, and water.

What is certain is Hippocrates’ crucial insistence that doctors should base their knowledge and decisions on careful observation of patients and the responses of sick people to remedies and treatments. Empirically grounded clinical experience, he taught, was the best guide to medicines and therapies that would above all, as his oath said, “abstain from doing the patient harm.” Medical treatments, he knew, could be powerfully injurious as well as therapeutic: Drugs could as easily poison as heal. Treatments administered without reliable evidence of their positive effects were irresponsible. The most startling innovation of Hippocrates’ medical doctrine was that it apparently made little or no mention of a divine role in sickness and its cures. This repudiated the basis of various medical cults in Greek religion, most famously that of the god Asclepius, which offered healing to patients who worshipped in his sanctuaries. It was a radical break with tradition to take the gods out of medicine, but that is what Hippocrates did, for the good of his patients, he believed.

There is unfortunately little direct evidence for the impact on ordinary people of the new developments in history and medicine, but their worries and even anger about the new trends in education, oratory, and philosophy with which Pericles was associated are recorded. These novel intellectual developments helped fuel tensions in Athens in the 430s B.C. They had a wide-ranging effect because the political, intellectual, and religious dimensions of life in ancient Athens were so intricately connected. A person could feel like talking about the city-state’s foreign and domestic policies on one occasion, about novel theories of the nature of the universe on another, and on every occasion about whether the gods were angry or pleased with the community. By the late 430s B.C., Athenians had new reasons to feel deep anxiety about each of these topics that mattered so deeply to their lives as citizens and individuals.