All through this book, you’ll find references to certain keys on Apple’s keyboards. “Hold down the  key,” you might read, or “Press Control-F2.” If you’re coming from Mac OS 9, from Windows, or even from a typewriter, you might be a bit befuddled.

key,” you might read, or “Press Control-F2.” If you’re coming from Mac OS 9, from Windows, or even from a typewriter, you might be a bit befuddled.

To make any attempt at an explanation even more complicated, Apple’s keyboards keep changing. The one you’re using right now is probably one of these models:

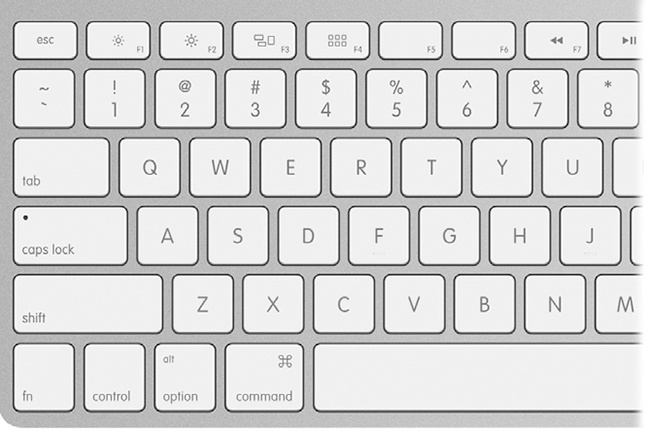

The current keyboards, where the keys are flat little jobbers that poke up through square holes in the aluminum (Figure 7-1). That’s what you get on current laptops, wired keyboards, and Bluetooth wireless keyboards.

The old, plastic desktop keyboards, or the white or black plastic laptop ones.

Here, then, is a guided tour of the non-typewriter keys on the modern Mac keyboard:

Tip

To see closeups of Apple’s current wired and wireless keyboards, visit www.apple.com/keyboard.

fn. How are you supposed to pronounce fn? Not “function,” certainly; after all, the F-keys on the top row are already known as function keys. And not “fun”; goodness knows, the fn key isn’t particularly hilarious to press.

What it does, though, is quite clear: It changes the purpose of certain keys. That’s a big deal on laptops, which don’t have nearly as many keys as desktop keyboards. So for some of the less commonly used functions, you’re supposed to press fn and a regular key. (For example, fn turns the

arrow key into a Page Up key, which scrolls upward by one screenful.)

arrow key into a Page Up key, which scrolls upward by one screenful.)Note

On most Mac keyboards, the fn key is in the lower-left corner. The exception is the full-size Apple desktop keyboard (the one with a numeric keypad); there the fn key is in the little block of keys between the letter keys and the number pad.

You’ll find many more fn examples in the following paragraphs.

Figure 7-1. On the top row of aluminum Mac keyboards, the F-keys have dual functions. Ordinarily, the F1 through F4 keys correspond to Screen Dimmer (

), Screen Brighter (

), Screen Brighter ( ), Mission Control (

), Mission Control ( ), and either Dashboard (

), and either Dashboard ( ) or Launchpad (

) or Launchpad ( ). Pressing the fn key in the lower-left corner changes their personalities.

). Pressing the fn key in the lower-left corner changes their personalities.Numeric keypad. The number-pad keys do exactly the same thing as the numbers at the top of the keyboard. But, with practice, typing things like phone numbers and prices is much faster with the number pad, since you don’t have to look down at what you’re doing.

Apple has been quietly eliminating the numeric keypad from most of its keyboards, but you can still find it on some models. And on some old Mac laptops, the numbers 0 through 9 were painted onto a block of letter keys near the right side (1, 2, and 3 were J, K, and L, for example). You could turn those letter keys into their numeric alter egos by pressing the fn key with your left hand.

Eventually, Apple eliminated this embedded-keyboard effect from its laptops, having discovered that almost nobody was using it.

,

,  (F1, F2). These keys control the brightness of your screen. Usually, you can tone it down a bit when you’re in a dark room or when you want to save laptop battery power; you’ll want to crank it up in the sun.

(F1, F2). These keys control the brightness of your screen. Usually, you can tone it down a bit when you’re in a dark room or when you want to save laptop battery power; you’ll want to crank it up in the sun. (F3). This one fires up Mission Control, the handy window-management feature described starting in Exiting Split Screen Mode.

(F3). This one fires up Mission Control, the handy window-management feature described starting in Exiting Split Screen Mode. or

or  (F4). Tap the

(F4). Tap the  key to open Dashboard, the archipelago of tiny, single-purpose widgets like Weather, Stocks, and Movies. See Dashboard for more about Dashboard.

key to open Dashboard, the archipelago of tiny, single-purpose widgets like Weather, Stocks, and Movies. See Dashboard for more about Dashboard.On recent Macs, the F4 key bears a

logo instead. Tapping it opens Launchpad, which is described starting in Tip.

logo instead. Tapping it opens Launchpad, which is described starting in Tip. ,

,  (F5, F6). Most recent Mac laptops have light-up keys, which is very handy indeed when you’re typing in the dark. The key lights are supposed to come on automatically when it’s dark, but you can also control the illumination yourself by tapping these keys. (On most other Macs, the F5 and F6 keys aren’t assigned to anything. They’re free for you to use as you see fit, as described in Tip.)

(F5, F6). Most recent Mac laptops have light-up keys, which is very handy indeed when you’re typing in the dark. The key lights are supposed to come on automatically when it’s dark, but you can also control the illumination yourself by tapping these keys. (On most other Macs, the F5 and F6 keys aren’t assigned to anything. They’re free for you to use as you see fit, as described in Tip.) ,

,  , and

, and  (F7, F8, F9). These keys work in the programs you’d expect: iTunes, QuickTime Player, DVD Player, and other programs where it’s handy to have Rewind, Play/Pause, and Fast Forward buttons.

(F7, F8, F9). These keys work in the programs you’d expect: iTunes, QuickTime Player, DVD Player, and other programs where it’s handy to have Rewind, Play/Pause, and Fast Forward buttons. ,

,  ,

,  (F10, F11, F12). These three keys control your speaker volume. The

(F10, F11, F12). These three keys control your speaker volume. The  key means Mute; tap it once to cut off the sound completely and again to restore its previous level. Tap the

key means Mute; tap it once to cut off the sound completely and again to restore its previous level. Tap the  repeatedly to make the sound level lower, the

repeatedly to make the sound level lower, the  key to make it louder.

key to make it louder.With each tap, you see a big white version of each key’s symbol on your screen, your Mac’s little nod to let you know it understands your efforts.

. This is the Eject key. When there’s a flash drive or a memory card in your Mac (or, less likely, a CD or a DVD), tap this key to make the computer spit it out.

. This is the Eject key. When there’s a flash drive or a memory card in your Mac (or, less likely, a CD or a DVD), tap this key to make the computer spit it out.Home, End. The Home key jumps to the top of a window, the End key to the bottom. If you’re looking at a list of files, the Home and End keys jump you to the top or bottom of the list. In Photos, they jump to the first or last photo in your collection. In iMovie, the Home key rewinds your movie to the very beginning. In Safari, it gets you to the top or bottom of the web page.

(In Word, they jump to the beginning or end of the line. But then again, Microsoft has always had its own ways of doing things.)

On keyboards without a dedicated block of number keys, you get these functions by holding down fn as you tap the

and

and  keys.

keys.Page Up, Page Down. These keys scroll up or down by one screenful. The idea is to let you scroll through word-processing documents, web pages, and lists without having to use the mouse.

On keyboards without a numeric keypad, you get these functions by pressing fn plus the

and

and  keys.

keys.Clear. Clear (on the old full-size keyboards only) gets rid of whatever you’ve highlighted, but without putting a copy on the invisible Clipboard, as the Cut command would do.

Esc. Esc stands for escape, and it means “cancel.” It’s fantastically useful. It closes dialog boxes, dismisses menus, and exits special modes like Quick Look, slideshows, screensavers, and so on. Get to know it.

Delete. The backspace key.

. Many a Mac fan goes for years without discovering the handiness of this delightful little key: the Forward Delete key. Whereas Delete backspaces over whatever letter is just to the left of the insertion point, this one (labeled “Del” on older keyboards) deletes whatever is just to the right of the insertion point. It comes in handy when, for example, you’ve clicked into some text to make an edit—but wound up planting your cursor in just the wrong place.

. Many a Mac fan goes for years without discovering the handiness of this delightful little key: the Forward Delete key. Whereas Delete backspaces over whatever letter is just to the left of the insertion point, this one (labeled “Del” on older keyboards) deletes whatever is just to the right of the insertion point. It comes in handy when, for example, you’ve clicked into some text to make an edit—but wound up planting your cursor in just the wrong place.The old full-size Apple keyboard has a dedicated key for this. On all other keyboards, you get this function by holding down fn as you tap the regular Delete key.

Return/Enter. Most Apple keyboards have a single Return/Enter key. On the old-style wide keyboards, there are separate Return and Enter keys (very few programs treat these keys as different, although Microsoft Excel is one of them). In any case, pressing Return wraps your typing to the next line. When a dialog box is on the screen, tapping the Return key is the same as clicking the confirmation button (like OK or Done).

Control. The Control key (represented by

in software menus) triggers shortcut menus, described on the following pages.

in software menus) triggers shortcut menus, described on the following pages.Option. The Option key (sometimes labeled Alt, and represented by

in menus) is sort of a “miscellaneous” key. It’s the equivalent of the Alt key in Windows. It lets you access secret features—you’ll find them described all through this book—and type special symbols. For example, you press Option-4 to get the ¢ symbol, and Option-Y to get the ¥ (yen) symbol.

in menus) is sort of a “miscellaneous” key. It’s the equivalent of the Alt key in Windows. It lets you access secret features—you’ll find them described all through this book—and type special symbols. For example, you press Option-4 to get the ¢ symbol, and Option-Y to get the ¥ (yen) symbol.Help. In the Finder, Microsoft programs, and a few other places, this key opens up the electronic help screens. But you’d guessed that.

As the previous section makes clear, the F-keys at the top of modern Mac keyboards come with predefined functions. They control screen brightness, keyboard brightness, speaker volume, music playback, and so on.

But they didn’t always. Before Apple gave F9, F10, and F11 to the fast-forward and speaker-volume functions, those keys controlled the Exposé window-management function described starting in Exposé.

So the question is: What if you don’t want to trigger the hardware features of these keys? What if you want pressing F1 to mean “F1” (which opens the Help window in some programs)? What if you want F9, F10, and F11 to control Exposé’s three modes, as they once did?

For that purpose, you’re supposed to press the fn key. The fn key (lower left on small keyboards, center block of keys on the big ones) switches the function of the function keys. In other words, pressing fn and F10 triggers an Exposé feature, even though the key has a Mute symbol ( ) painted on it.

) painted on it.

But here’s the thing: What if you use those F-keys for software features (like Cut, Copy, Paste, and Exposé) more often than the hardware features (like brightness and volume)?

In that case, you can reverse the logic, so that pressing the F-keys alone triggers software functions and governs brightness and audio only when you’re pressing fn. To do that, choose  →System Preferences→Keyboard. Turn on the cryptically worded checkbox “Use F1, F2, etc. as standard function keys.”

→System Preferences→Keyboard. Turn on the cryptically worded checkbox “Use F1, F2, etc. as standard function keys.”

And that’s it. From now on, you press the fn key to get the functions painted on the keys ( ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , and so on).

, and so on).