If you’re setting up a Standard/Managed account, the Parental Controls feature affords you the opportunity to shield your Mac—or its very young, very fearful, or very mischievous operator—from confusion and harm. This set of options is helpful to remember when you’re setting up accounts for students, young children, or easily intimidated adults. (This checkbox is available for Admin accounts, too, but turning it on produces a “Silly rabbit—this is for kids!” sort of message.)

You can specify how many hours a day each person is allowed to use the Mac, and declare certain hours (like sleeping hours) off-limits. You can specify exactly who your kids are allowed to communicate with via email (if they use Mail) and instant messaging (if they use Messages), what websites they can visit (if they use Safari), what programs they’re allowed to use, and even what words they can look up in the Mac Dictionary.

Here are all the ways you can keep your little Managed account holders shielded from the Internet—and themselves. For sanity’s sake, the following discussion refers to the Managed account holder as “your child.” But some of these controls—notably those in the System category—are equally useful for people of any age who feel overwhelmed by the Mac, are inclined to mess it up by not knowing what they’re doing, or may be tempted to mess it up deliberately.

Note

If you apply any of these options to a Standard account, then the account type listed on the Users & Groups panel changes from “Standard” to “Managed.”

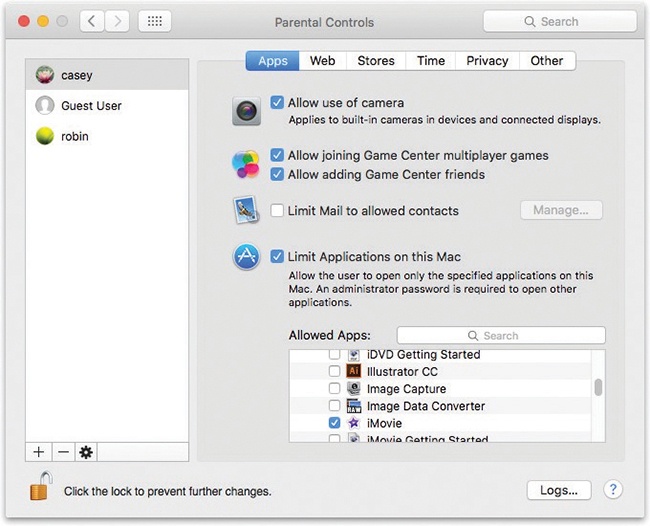

To begin, click Open Parental Controls at the bottom of the Users & Groups pane. Click Enable Parental Controls, if necessary. After you enter your administrator-account password, you see the screen shown in Figure 13-5.

Figure 13-5. In the Parental Controls window, you can control the capabilities of any account holder on your Mac. If you turn on Limit Applications, then the lower half of the Apps tab window lets you choose applications (from the Mac App Store and others), and even Dashboard widgets, by turning on the boxes next to their names. (Expand the flippy triangles if necessary.) Those are the only programs the account holder will be allowed to use. The search box helps you find certain programs without knowing their categories.

On this tab (Figure 13-5), you can limit what your Managed-account flock is allowed to do on the Mac—including which programs they can use. (Limiting what people can do to your Mac when you’re not looking is a handy feature under any shared-computer circumstance. But if there’s one word tattooed on its forehead, it would be “Classrooms!”)

For example, here are some of the options on the Parental Controls screen:

Allow use of camera. With this control, you can prevent your kids from filling up your hard drive with photos of their body parts.

Limit Mail to allowed contacts. Here you can control your kid’s access to correspondents by email.

Turn the checkbox on and then click Manage. In the next dialog box, you can build a list of email addresses corresponding to the people you feel comfortable letting your kid exchange emails with. Click the + button below the list, type a few letters of the person’s name, click the correct result (drawn from your Contacts app). Lather, rinse, repeat.

The best part is at the top—the “Send requests to” option. Turn it on and fill in your own email address.

Now, when your youngster tries to send a message to someone who’s not on the approved list, she gets a message that says “You do not have permission to send messages to this email address.” If she clicks Ask Permission, then your email address receives a permission-request message.

If you’re convinced that the would-be correspondent is not, in fact, a stalker, you can grant permission by clicking Always Allow. Your young ward gets the good news the next time she visits her Drafts folder, where the message has been awaiting word from you, the Good Parent.

Note

This feature works only in Mail. It doesn’t involve other email programs, like Microsoft Outlook. If you’re worried about your efforts being bypassed, block access to those programs using the Limit Applications feature described below.

When your underling fires up Messages or Mail, she’ll discover that her buddies list is empty except for the people you’ve identified.

Handling the teenage hissy fit is your problem.

Limit Applications on this Mac. When you turn this on, the list shown at bottom in Figure 13-5 springs to life. It’s all your programs (Other Apps) and all the apps in your Utilities folder. Only checked items will show up in the account holder’s Applications folder. (If you don’t see a program listed, then use the search box, or drag its icon from the Finder into the window.)

This feature is designed to limit which websites your kid is allowed to visit.

Frankly, trying to block the racy stuff from the web is something of a hopeless task; if your kid doesn’t manage to get around this blockade by simply using a different browser, then he’ll just see the dirty pictures at another kid’s house. But at least you can enjoy the illusion of taking a stand, using approaches with three degrees of severity:

Allow unrestricted access to websites. No filtering. Anything goes.

Try to limit access to adult websites automatically. The words “try to” are Apple’s way of admitting that no filter is foolproof.

In any case, macOS analyzes what’s on a web page that you try to call up and filters out websites with naughty material. These sites won’t appear in Safari while this account holder is logged in. By clicking Customize and then editing the “Always allow” and “Never allow” lists, you can override its decisions on a site-at-a-time basis.

Allow access to only these websites. This is the most restrictive approach of all: It’s a whitelist, a list of the only websites your youngster is allowed to visit. It’s filled with kid-friendly sites like Disney and Discovery Kids, but of course you can edit the list by clicking the + and — buttons below the list.

Concerned that your little angel might run up bank-busting bills buying stuff from Apple’s online music, movie, app, and book stores? You wouldn’t be the first one.

That’s why Apple gives you checkboxes that let you block access to the iTunes Store (music, movies, TV shows, apps) and the iBooks Store. (There’s a separate checkbox for iTunes U, a category of free educational videos. Apple reasons that that corner of the iTunes Store might be OK.)

Here, too, are options that shield your youngster’s eyes and ears from music, movies, books, and apps that contain sexy stuff or bad words. You can limit movie watching to those with, for example, a PG rating at worst. The “Apps to” pop-up menu even lets you specify an appropriate age group for permitted apps. If you choose “up to 9+,” for example, your well-parented offspring will be allowed to use all App Store programs that have been rated for use by anyone who’s 9 or older.

Clever folks, those Apple programmers. They must have kids of their own.

They realize that some parents care about how many hours their kids spend in front of the Mac, and that some also care about which hours (Figure 13-6):

How much time. In the “Weekday time limits” and “Weekend time limits” sections, turn on “Limit weekday use to” or “Limit weekend use to” and then adjust the sliders.

Which hours. In the “Bedtime” section, turn on the checkbox for either “School nights” or “Weekend,” and then set the hours of the day (or, rather, night) when the Mac is unavailable to your young account holder.

In other words, this feature may have the smallest pages-to-significance ratio in this entire book. Doesn’t take long to explain it, but it could bring the parents of Mac addicts a lot of peace.

Tip

When time limits have been applied, your little rug rats can now check to see how much time they have left to goof off on the Mac before your digital iron fist slams down. When they click the menu-bar clock (where it now says the current time), a menu appears, complete with a readout that says, for example, “Parental Controls: Time Remaining 1:29.” Good parenting comes in many forms.

Figure 13-6. If this account holder tries to log in outside the time limits you specify here, she’ll encounter only a box that says “Computer time limits expired.” She’ll be offered a pop-up menu that grants her additional time, from 15 minutes to “Rest of the day”—but it requires your parental consent (actually, your parental password) to activate.

The Manage Privacy button takes you directly to the System Preferences panel described in Tip. It’s where your kid has control over which apps access Contacts, Calendar, and so on.

Below that, the “Allow changes to” checkboxes exist to protect your privacy. Turning off a checkbox means that no app your kid uses can make any changes to the apps listed here.

This tab offers a few miscellaneous options, including the following:

Turn Off Dictation. Those kids can’t turn on the Dictation feature. They can talk only to you and other humans.

Disable editing of printers and scanners. When this checkbox is on, your underlings aren’t allowed to change your Mac’s printer or scanner settings. You wouldn’t want them deleting or installing printers, would you?

Block CD and DVD burning in the Finder. In a school lab, for example, you might want to turn off the ability to burn discs (to block software piracy).

Restrict explicit language in Dictionary. MacOS comes with a complete electronic copy of the New Oxford American Dictionary. And “complete,” in this case, means “It even has swear words.”

Turning on this option is like having an Insta-Censor™. It hides the naughty words from the dictionary whenever your young account holder is logged in.

Use Simple Finder. Use this option only if you’re really concerned about somebody’s ability to survive the Mac—or the Mac’s ability to survive that somebody. Read on.

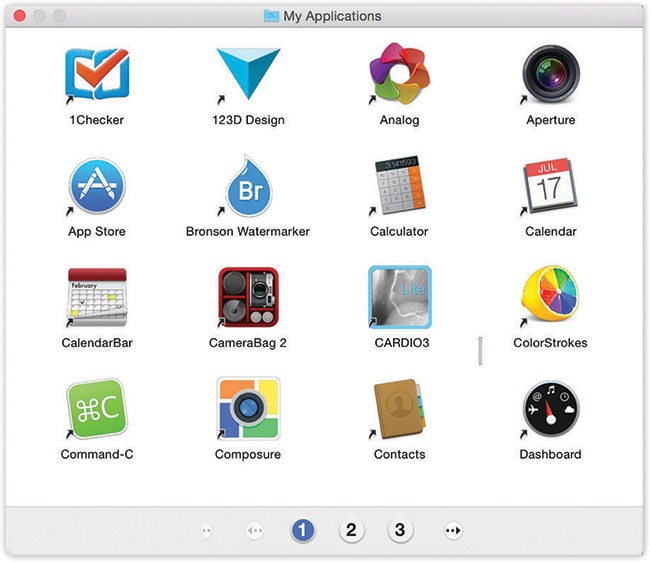

Suppose you’ve been given a Simple Finder account. When you log in, you discover the barren world shown in Figure 13-7. There are only three menus ( , Finder, and File), a single onscreen window, no hard drive icon, and a bare-bones Dock. The only folders you can see are in the Dock. They include these:

, Finder, and File), a single onscreen window, no hard drive icon, and a bare-bones Dock. The only folders you can see are in the Dock. They include these:

My Applications. This folder holds aliases of the applications that the administrator approved on the Apps tab shown in Figure 13-5. They appear on a strange, fixed icon view called “pages.” List and column views don’t exist. As a Simple person, you can’t move, rename, delete, sort, or change the display of these icons—you can merely click them. If you have too many to fit on one screen, you get numbered page buttons beneath them, which you can click to move from one set to another.

Documents. Behind the scenes, this is your Home→Documents folder. Of course, as a Simple Finder kind of soul, you don’t have a visible Home folder. All your stuff goes in here.

Figure 13-7. The Simple Finder doesn’t feel like home—unless you’ve got one of those Spartan, space-age, Dr. Evil–style pads. But it can be just the ticket for less-skilled Mac users, with few options and a basic one-click interface. Every program in the My Applications folder is actually an alias to the real program, which is safely ensconced in the off-limits Applications folder.

Shared. This is the same Shared folder described in Figure 13-11. It’s provided so that you and other account holders can exchange material. However, you can’t open any of the folders here, only the documents.

Trash. The Trash is here, but selecting or dragging any icon is against the rules, so you’re left with no obvious means of putting anything into it.

The only program with its own icon on the Dock is the Finder.

To keep things extra simple, macOS permits only one window at a time to be open. It’s easy to open icons, too, because one click opens them, not two.

The File menu is stunted, offering only a Close Window command. The Finder menu gives you only two options: About Finder and Run Full Finder. (The latter command prompts you for an administrator’s name and password, and then turns back into the regular Finder—a handy escape hatch. To return to Simple Finder, just choose Finder→Return to Simple Finder.)

The  menu is really bare-bones: You can Log Out, Force Quit, or go to Sleep. That’s it. And there’s no trace of Spotlight.

menu is really bare-bones: You can Log Out, Force Quit, or go to Sleep. That’s it. And there’s no trace of Spotlight.

Otherwise, you can essentially forget everything else you’ve read in this book. You can’t create folders, move icons, or do much of anything beyond clicking the icons that your benevolent administrator has provided. It’s as though macOS moved away and left you the empty house.

Although the Simple Finder is simple, any program (at least, any that the administrator has permitted) can run from Simple Finder. A program running inside the Simple Finder still has all its features and complexities—only the Finder itself has been whittled down to its essence.

In other words, Simple Finder is great for streamlining the Finder, but novices won’t get far combating their techno-fear until the world presents us with Simple iMovie, Simple Mail, and Simple Microsoft Word. Still, it’s better than nothing.