CHAPTER 4

PLANTS

SHRUBS MOST CLEARLY define the chaparral. These densely intertwined, multistemmed, woody, evergreen plants make up the continuous blue green blanket that appears from a distance to gently cover the hillsides. Up close, however, the shrubs grow in nearly impenetrable stands of tough drought-and fire-hardy plants. In ecological terms shrubs are dominant, shaping the physical and biological environment for all other species. Shrubs are also what burn so fiercely during a fire. The stems and leaves that accumulate over many years provide the fuel. Shrubs appear uniform over large areas because their life cycles are restarted with every fire, so all the plants in a given area are the same age.

Herbaceous plants appear in numbers only when the shrubs are burned away. Long unseen, fire-stimulated wildflowers and subshrubs emerge from seeds in the soil. In the first few years after fire, herbs (short-lived plants lacking permanent stems) and subshrubs (plants with soft upper stems that often die back to the woody, lower parts during summer) temporarily trade places with the woody shrubs as the most numerous and extensive plant types. This reversal of roles may last for the first three to five years after fire until the shrubs reassert their dominant place in the community. The shrubs maintain this dominance until the next fire (see The Fire Cycle in chapter 3).

Trees (plants with a single, thick, woody trunk and usually upward of 25 feet tall) are occasionally associated with chaparral, especially on moist slopes, in ravines, and at higher elevations. Some species of cypress and the bigcone Douglas fir are found embedded in the chaparral, but for the most part, the common oaks and pines of California do not form a significant part of the chaparral community.

Few chaparral plant species are found in other habitats or plant communities. They are different in this respect from many species of animals that use the chaparral for food, nesting, or other resources but also spend time elsewhere. One of the special features of the chaparral flora is habitat fidelity.

The plants of the chaparral are uniquely adapted to this habitat, whether their period of abundance is during the long fire free periods when shrubs dominate, or confined to the period immediately after fire when the shrubs are no longer present. Seeds are eaten by many kinds of insects, birds, and mammals, and with few exceptions animals move seeds only short distances. Seeds that are not destroyed remain in the area to reproduce the same plant community again following the next fire. So, unlike the seeds of many plants, those of chaparral natives are not regularly dispersed far away from the parent plant.

In this book, we treat the common and dominant shrub species and shrub families of the mature chaparral first, as they are the most conspicuous plants and provide overall structure and organization to the community. Those trees that are likely to be encountered near chaparral are also briefly discussed. This is followed by descriptions of the common subshrubs and herbs and their families. These are the types of plants that dominate chaparral immediately after fire. California has an extraordinarily rich flora overall, and the chaparral is responsible for much of that richness. Drawings and photographs are provided to aid in recognizing the major chaparral plants discussed here.

An Evergreen, Shrubby Vegetation

The shrubby growth form and the dense and often impenetrable nature of chaparral are adaptations to the rigors of a mediterranean climate. These rigors include extended periods of heat and drought interspersed with rain of quite variable amount and duration. In addition, chaparral soils are often coarse textured and poor in nutrients. Water moves quickly through this soil so that the plants have only a short time to take advantage of the moisture. Most trees and broad-leaved plants need a regular source of moisture, moderate temperatures, and reasonably fertile soils to grow well. With the poor soils and unpredictable water supplies of the chaparral these criteria are not all met, and only specially adapted plants can make it their home. Fire adds another physical variable that also eliminates some types of plants that might otherwise overcome obstacles to life in the chaparral.

Chaparral shrubs are woody, tough, and once established, capable of hanging on in difficult environments. Shrubs do not require as much energy to live as do trees, because of their smaller stature and more slender stems and branches. In addition, should one of the main stems prove to be in a bad location relative to water or sunlight, it may be allowed to die (self-pruning) without killing the entire plant. The many dead stems found beneath and within the mature chaparral canopy attest to this harsh but effective accounting system. The living tissue in the main woody trunks and stems is often reduced to only small areas as a result of the successive loss of branches over time. These shrubs also quickly develop deep root systems and can persist and indeed flourish on exceptionally steep slopes (pls. 10, 29). In the chaparral many shrubs have an enlarged woody base, called a burl or root crown, from which the main stems emerge. As mentioned earlier, the function of the burl is to produce new shoots after damage by fire or other causes. It is one of the features that make the chaparral shrubs so resilient.

The leaves are the energy producing part of the shrubs. It is their job to perform photosynthesis and make energy available as sugars and other carbohydrates for growth and reproduction. To do this they must have sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide and be able to exchange gasses with the air. This means that leaves are also the places where the demand for water is greatest and where the most protection is needed to avoid drying out. Chaparral shrub leaves do not wilt and rarely show visible signs of water loss even though they can be very dry (less than 10 percent water). Conditions favorable for high photosynthesis rates are not present during the entire day or at all seasons. Herbivores nibbling the leaves, and water lost through the surface further decrease productivity. To protect themselves from the costs of repair associated with wilting or mechanical damage, chaparral plants have tough, rigid leaves that are structurally reinforced with hard, non-photosynthetic tissue (sclerenchyma). This heavy reinforcement makes hard (sclerophyllous) leaves (pl. 34) that retain their structural integrity through the seasons. The typical description of chaparral, in scientific publications, is an evergreen sclerophyllous shrub vegetation. “Evergreen” refers to the fact that the leaves persist for more than one growing season and typically remain green throughout their life on the plant. This is different from deciduous plants, which shed their leaves during fall or when environmental conditions are unfavorable and then produce new leaves the next growing season. Chaparral shrub leaves may live for one to seven years, depending on the species and the plant's microclimate.

Chaparral shrubs grow so close to one another that the branches of adjacent plants are interlaced. These densely intertwined branches shade not only the ground but also the plants themselves. Twisted branches at many levels within the canopy, combined with varying angles of exposure to the sun for vertical or fasciculate (clustered) leaves, means that not every leaf will be in full sun all the time (pl. 41). The partial shading of leaves can be important in this very sunny climate. The leaves actually perform more efficiently during the summer months with less than maximum exposure to the sun.

Plate 34. The leaves of chaparral shrubs, like this lemonadeberry, are evergreen and hard. They are often oriented vertically to reduce heating by the sun and may have waxy or hairy surfaces to retard evaporation. A cluster of flower buds sits among the stiff, thick leaves.

All organisms live between their limits and within their tolerances. The plant growth form that meets these specifications in a mediterranean climate is the woody, evergreen shrub. This common solution to the rigors of the environment can be seen clearly in the five areas of mediterranean climate around the world. Whether in Western Australia, South Africa, Chile, California, or Europe, many parts of mediterranean climate regions are dominated by evergreen sclerophyllous shrubs (pls. 17–20). The water-loving plants we commonly use to landscape our gardens and public spaces cannot survive without frequent and regular watering in this climate.

Common Shrubs and Shrub Families

More than 100 species of evergreen shrubs occur in the chaparral statewide, but only a few are common throughout. Also, only a small number of plant families contain most of the chaparral shrubs. It is, therefore, relatively easy to recognize most of the widespread shrubs of the chaparral, such as chamise, manzanita, and ceanothus. This is not the case in many other places in the world, and it is a distinguishing characteristic of the California chaparral. The most abundant and commonly encountered chaparral shrubs are found in five families. These are the rose, the buckthorn, the heath, the oak, and the sumac families. Several other plant families occur in the chaparral, as well, and can be locally common. These less widespread families are discussed following the review of the five that are most commonly represented.

The Rose Family (Rosaceae)

The rose family contains several of the most common and widespread shrub species in the chaparral. As a group, species of chaparral roses are the tough, resilient, woody survivors of an ancient vegetation that covered much of the western United States millions of years ago. These include the plant that most characteristically defines the California chaparral, chamise, and the plant that gave Hollywood its name, California holly, or as it is more commonly called today, toyon. Other chaparral members of the family include the holly-leafed cherry, mountain mahogany, and a cousin of chamise, red shank. Outside of the chaparral this family includes economically important plants such as apples, cherries, peaches, plums, pears, strawberries, raspberries, and of course, roses.

Chamise

The most abundant and ubiquitous shrub of the chaparral is chamise (Adenostoma fasciculatum) (pl. 35). It has a range that encompasses almost the entire latitudinal spread of chaparral from northern California to Baja California. The cover photograph shows it growing near the northern limit of its distribution, mixed with other species of chaparral shrubs and trees. It is also the most common species of shrub in over 50 percent of the chaparral statewide. It often grows in almost pure stands where very few shrubs of other species are present. The average chamise shrub is four to six feet tall. It can be readily recognized by its small (one-half inch or less), dark green, needlelike leaves grouped together in numerous clusters (called fascicles) dotted along the pale gray stems (pl. 11, fig. 7). Usually, several stems arise from a burl at the base of the shrub. This species resprouts vigorously after fire, and an individual plant may survive for hundreds of years.

Plate 35. Chamise, a member of the rose family, is the most common shrub in the chaparral throughout California. Here, blooms are seen on near and far slopes.

Chamise has a short growing season, starting in late February or March and ending after the rains, usually sometime in June. Growth is from the tips of existing branches, and new lengths of growing stem can be seen readily in spring. The reddish tinge and soft texture of the new growth clearly distinguishes it from the harder, gray-barked branches of prior seasons. The plants flower in early summer, after their spurt of growth. The flowers are small with creamy white, frothy-looking blossoms densely packed into clusters up to eight inches long at the ends of the branches. A June hillside of flowering chamise transforms the appearance of the chaparral from green to white, because countless flowers temporarily obscure the foliage (pl. 35).

The creamy white of new flowers is replaced by a rusty red brown as the seeds develop and flower parts dry out, as seen in the foreground of the book's cover photograph. The shrubs are thickly covered by millions of flowers during spring, but only a small percentage of the seeds produced are capable of germinating. Of those that are viable, fewer still will ever have the opportunity to sprout. This is because most of the seeds are eaten, decay, or become buried too deeply in the soil to germinate later. It is important to the long-term survival of this species to have new plants arise from seed after each fire because even though they usually resprout, some mature shrubs are killed by each fire. Because of its excellent survival abilities in the face of drought, heat, and fire, chamise thrives in some of the most exposed and difficult places in the chaparral (pl. 15).

Figure 7. Chamise has small leaves born in fascicles, or clusters. The detail to the right shows an enlarged flower that has five white to cream-colored petals, and a close-up of the fascicles.

Red Shank

Another member of the genus Adenostoma, red shank (A. sparsifolium), also called ribbonwood, is found over a narrower geographical range than chamise. It occurs only in central and southern California, from San Luis Obispo County in the Central Coast Ranges to the southern limit of chaparral in the Sierra San Pedro Martir of Baja California. Within these limits, it seems to replace chamise in places with more moisture or better soil. Red shank tends to grow in pure stands, surrounded by chamise, or by manzanita (Arctostaphylos spp.) and ceanothus (Ceanothus spp.) on the higher slopes. Curiously, it does not naturally occur in the Transverse Ranges of southern California, although when it is planted there among chamise and other species of chaparral shrubs it grows quite well and regenerates after fire. Red shank and ribbonwood are names given to this plant because of the loose shaggy red bark that peels off in long strips from the major stems. The shrubs are tall by chaparral standards, often growing to heights of 12 to 20 feet (pl. 36). The leaves are similar in size to those of chamise and are conspicuously resinous (fig. 8). They grow in linear clusters at the end of the branches, in loose broomlike sprays. Given the height of these shrubs and the leaf arrangement at the ends of the branches, it is sometimes possible to walk upright beneath the long, wandlike branches. Red shank has many small, creamy white flowers, similar to those of chamise, but in open clusters six to eight inches long. These may be dense at the ends of individual branches but rarely hide the foliage as chamise blossoms do. As with chamise, a late spring flush of new leaves and stems is followed by flowering and seed production. Red shank resprouts well and also produces new seedlings after fire from seed stored in the soil.

Plate 36. Red shank, shown here in flower, is a close relative of chamise. It is a remnant of an ancient vegetation that existed in southern California before the modern chaparral.

Figure 8. A close-up view of the leaves, branchlets, and flowers of red shank. The main trunks have red bark often seen hanging in shreds along the stems.

Toyon

Another member of the rose family, toyon (Heteromeles arbutifolia), also called Christmas berry or California holly, is one of the best known and most widespread of all chaparral shrubs. This is the plant that gave Hollywood its name, and it remains a common shrub in the Hollywood Hills today (pl. 4). Toyon is found in chaparral from northern California to Baja California and from the Coast Ranges to the foothills of the Sierra. This species favors cooler east- and north-facing slopes and canyons in the chaparral. Toyon grows as scattered individuals among other shrub species rather than in pure stands. This is likely due to birds eating the berries and later dropping the seeds randomly among other shrubs. Toyon is often one of the tallest chaparral shrubs, reaching a height of up to 20 feet. It has sclerophyllous evergreen leaves with serrated and bumpy margins, but the leaves are not prickly like those of holly (fig. 9). The mature leaves of this species are two to four inches long and about a third as wide and may live as long as seven years under good conditions. One characteristic of the young leaves is a reddish color and a characteristically bitter odor when crushed. This odor is due to the presence of cyanide-containing chemicals that are accumulated there by the plant to deter herbivores from eating the tender foliage. Despite this, tender young toyon leaves are a favored food of Mule Deer (Odocoileus hemionus).

Flowering takes place in the late summer after a spring flush of new leaves has been produced. The small white flowers are produced in broad flat clusters up to 10 inches across and scattered over the plant. The characteristic pom-poms of red berries (pl. 4) develop over several months and are most conspicuous in winter. The common names California holly and Christmas berry were given to this shrub because of its superficial resemblance to English holly (Ilex aquifolium) with its winter clusters of bright red berries and contrasting dark green leaves. Early immigrants with English roots used it in their California homes for “traditional” Christmas decorations. The practice of decorating with the berries and branches became so widespread and destructive in the Los Angeles area during the 1920s that a state law was passed prohibiting the harvesting of this plant. Toyon, its other common name, is derived from an old Spanish term for “canyon,” the habitat preferred by this species. It is a vigorous resprouter after fire (pl. 24) and also produces seedlings. Unlike many other chaparral species, seeds of this species can and do germinate between fires.

Figure 9. Foliage, flower, and fruit cluster of toyon, a common shrub in moist canyons throughout the state.

The one-quarter inch diameter toyon berries have the same structure as tiny apples, and they are edible by humans after they are heated to remove the bitter taste. Both Indians and early settlers cooked toyon berries lightly by boiling, steaming, or roasting. Mexican and American settlers made a cider from the berries, and Indians used an extract of the bark for various aches and pains. Early Spanish settlers made a sort of pudding by baking the berries slowly with sugar and used this as a pie filling. These fruits are highly prized by numerous species of birds, as well. They will often flock to the same bush day after day in winter until all the berries have been consumed.

Toyon was introduced to cultivation in Europe 200 years ago, shortly after Europeans began exploring the flora of California. It is also widely grown in parks and gardens throughout California today.

Mountain Mahogany

A prominent species of steep slopes and rocky, dry chaparral is mountain mahogany (Cercocarpus betuloides). It is found from Oregon to Baja California, in the cismontane of southern California, and out to the Channel Islands. Individuals may range from six to 20 feet tall. Typically the shrubs are scattered, with visible space between individuals when they are found on steep slopes, but this species may grow in dense aggregations in other areas. Mountain mahogany is often found in association with the chaparral shrubs chamise, ceanothus, and manzanita. Mountain mahogany leaves, one-half to one inch long, are ridged and grooved in an almost fanlike pattern and are dark green on the top surface, with white, hairy lower leaf surfaces. The stems are also almost white and easily seen because of the sparse nature of the leaves. It has white flowers about one-quarter inch across, spaced along the upper branches (fig. 10). Flowering may start in early spring and continue through May, when the fruits and seeds mature. While flowering often makes chaparral shrubs conspicuous, it is the fruiting season of mountain mahogany that calls most attention to this plant. Thousands of pale feathery plumes extend out from the branches all over the outside of the shrub canopy and, when backlit, give the shrubs a silvery halo. The bottom of the spiral plume is attached to a seed, which is enclosed in a structure that resembles a pointed drill tip. When the fruits eventually drop to the soil they work their way into the ground as the wind pushes the spiral plume around in a circle. The seed is actually screwed into the ground. Once the seed is embedded in the soil, the feathery top breaks off and blows away. Mountain mahogany resprouts and also reproduces from seed after fire. Two other members of the genus are desert mountain mahogany (C. ledifolius), found in particularly dry areas in the mountains and in desert chaparral, and small-flowered mountain mahogany (C. minutiflorus), a species restricted to chaparral of San Diego County and Baja California. The foliage of mountain mahogany is a favored food of deer as well as domestic browsing animals.

Figure 10. Foliage, flowers, and feather-tailed fruits of mountain mahogany. This species often grows on steep open slopes where other chaparral shrubs do not.

Holly-leafed Cherry

In contrast to mountain mahogany, holly-leafed cherry (Prunus subsp. ilicifolia) prefers ravines, north-facing slopes, and relatively moist environments within the chaparral. This species is found in the chaparral of the Coast Ranges from Napa County south to Baja California and on the Channel Islands (fig. 11). Holly-leafed cherry is in the same genus as the cultivated cherry. It can range from a shoulder-height shrub to a treelike form 20 feet tall, usually with more than one major trunk. It has ruffled, shiny, dark green leaves three-quarters to two inches long with prominent spiny margins. The small white flowers are born in branched sprays (racemes) several inches long and can be seen in spring and early summer. When the sweet tasting fruits ripen to a dark purple they are clearly recognizable as cherries, although often smaller than the commercial variety. The fruits are much sought after by birds. Holly-leafed cherry resprouts vigorously after fire but like toyon does not require fire to reproduce. Seedlings are occasionally observed in openings and canyon bottoms in areas of mature chaparral. A subspecies of this species, the Catalina cherry (P. ilicifolia subsp. lyonii), from the Channel Islands, is notable for its height and bright, shiny green leaves. These features make this variety popular as an ornamental plant along the coast and in the valleys of California.

The Buckthorn Family (Rhamnaceae)

The buckthorn family is abundantly represented in the California chaparral, particularly by species of ceanothus, also called California lilac. The chaparral is the center of ceanothus worldwide. Many endemic species have evolved in particular chaparral locations and on special soil types. One of the most interesting questions to students of the chaparral is why there are so many species of ceanothus in California and the chaparral when there are few elsewhere. Much remains to be discovered about these species, as the answer is not yet known. Nearly every part of the chaparral has one or more species of this genus, making ceanothus as characteristic of the chaparral as the ubiquitous chamise (pl. 37). Other members of the buckthorn family, spiny redberry, holly-leaf redberry, and California coffeeberry, are also found in the chaparral across the state, often in combination with ceanothus. This is a hardy family in the chaparral. All of the buckthorns can form dense, wiry, and often spiny thickets, making them among the most difficult parts of the chaparral to penetrate.

Figure 11. Holly-leafed cherry has two geographical forms, or subspecies. The smooth, large-leafed form (above) comes from the Channel Islands and is commonly called Catalina cherry. The spinier and smaller leafed form (below) is usually referred to simply as holly-leafed cherry and is found in the chaparral throughout mainland California.

Plate 37. Ceanothus covers broad expanses of chaparral in the Santa Ynez Mountains above Santa Barbara. The paler ridges and upper slopes show the cream colored flowers of bigpod ceanothus. Chamise mixed with manzanita covers the hill in the immediate foreground.

Ceanothus

Along with chamise, ceanothus (Ceanothus spp.) is found in nearly all chaparral areas throughout the state. Of the more than 40 species in the chaparral statewide, nearly every part of the chaparral will have at least one species of ceanothus and generally more. A given hillside may be dominated by one species or have a patchy mixture of several species often mixed with the ubiquitous chamise. Each ceanothus species prefers a slightly different location along the slopes. Species also grow at many different elevations and exposures across the state. Ceanothus species vary collectively in size from dense low-growing mats to individuals 15 to 30 feet tall. The leaves of ceanothus species can be from one-half to two inches long and vary from relatively smooth, uniformly pale-colored types to tough, thick ones that have a bumpy, wrinkled appearance and may be strongly bicolored dark green and white (figs. 12–14). The leaves are important in distinguishing the two main groups of species within the ceanothus genus. The characteristic that gives ceanothus its other common name, California lilac, is profuse clusters of sweet-smelling white, blue, or purple blossoms that cover the shrubs in late winter and spring (pl. 3). The individual flowers are quite small, about one-tenth inch across, but occur in large clusters that are superficially similar to lilacs when viewed from a distance. Each species of ceanothus produces flowers over approximately a period of two months between January and June. All the members of a particular population of ceanothus tend to flower at once, and each species blooms according to its own internal clock. This produces a patchwork landscape with splashes of color that come and go over a period of several months, creating a traveling kaleidoscope of creamy white and blue, sequenced by time, elevation, and species. These displays are sometimes bright enough to be seen from an airliner. The heavy, sweet odor of countless flowers can be detected for long distances, and ceanothus nectar is an important food for honeybees (Apis spp.) and many other insects.

Ceanothus fruits are explosive when ripe. The explosion occurs from tension that builds within the structure of the three-chambered fruit as it dries out in warm weather. There is enough force to make a clear popping sound and to launch seeds in all directions with considerable force and velocity. The simultaneous explosion of many capsules creates a small storm of flying seeds. The newly released seeds of most ceanothus species are dark and shiny so that the ground looks conspicuously peppered with them. They are also numerous. For example, beneath hoaryleaf ceanothus (C. crassifolius) (fig. 14) in a good year there may be 10,000 to 12,000 seeds per square yard! Initial seed densities, even when quite high, drop steeply in a matter of few weeks. Those seeds that escape the keen eyes and noses of the industrious rodents, birds, and ants are buried in the soil, where they become part of the soil seed bank and await the next fire for an opportunity to germinate.

Figure 12. Buck brush is one of the nonsprouting species of subgenus Cerastes. The corky swellings at the base of the leaves are characteristic of species of this subgenus. All ceanothus have three-chambered fruits that discharge explosively when ripe.

Figure 13. Ceanothus tomentosus has white to light purple flowers and shiny, dark green leaves. Characteristic of members of the resprouting subgenus Ceanothus, the leaves of this species have three main veins.

Ceanothus species are capable of adapting to a wide range of conditions. This ability is valued in the production of horticultural hybrids, meaning crosses between different species. About 20 species of ceanothus are popularly planted as ground cover, on steep slopes, for garden contrast and color, and along roadsides. Hybrids can be especially suited for a particular region's climate and soil, as well as valued for their decorative nature. As a group, ceanothus grows in almost any habitat in the mediterranean zone of California with full sun and well-drained soil, requiring little or no water beyond that provided by nature. In addition to the ability to hybridize readily, ceanothus is also tolerant of a wide range of soil types, including serpentine soils, which are poisonous to most other plants. This tolerance is thought to be an important factor in the formation of so many species in different habitats throughout the state. Half of the 40 California species of ceanothus are narrow endemics, in extreme cases limited to a single site. Examples of very narrow endemics are the endangered Pine Hill ceanothus (C. roderickii) and Coyote Valley California lilac (C. ferrisae), limited to serpentine outcrops in El Dorado County and Santa Clara County, respectively.

Figure 14. Foliage, flowers, and ripening fruit (center right) of hoaryleaf ceanothus, another nonsprouting member of the subgenus Cerastes. The leaves are small, hard, and densely hairy on the underside.

Eighteen ceanothus species are on the Species of Special Concern list compiled by the California Department of Fish and Game as part of the Natural Diversity Database (NDDB). This list contains species and subspecies that are rare, limited in distribution, or legally listed as rare, threatened, or endangered by the state of California or the federal government. Because of the narrow distribution of many of these species, habitat destruction is one of the major problems for surviving individuals.

Taxonomists divide the ceanothus genus into two groups: subgenus Ceanothus and subgenus Cerastes. These two groups differ from each other in two broad characteristics: the leaf type and the ability to resprout after fire.

The subgenus Ceanothus comprises species that have leaves with three prominent veins. The leaves are arranged alternately along the stem (fig. 13). These species also have the ability to resprout after fire. Leaves vary from a smooth, almost succulent condition, to hard and roughly textured. In extreme cases, the texture of the leaf may make it difficult to identify the three veins. In this case it is best seen by looking at the underside of the leaf, where the veins are more prominent. The stems are often a smooth pale gray or green near the leaves but become rougher and more conspicuously brown and gray as the bark thickens near the stem base. The burls are sometimes irregular in shape and may not be obvious on steep slopes, where they can be buried by loose soil and litter. Some examples of a resprouting species are chaparral white thorn (C. leucodermis) (pl. 38), common in southern California, coast white thorn (C. incanus) of the Central Coast Ranges, and tobacco brush (C. velutinus) of northern California.

The members of subgenus Cerastes have only one main vein running down the center of the leaf, and the leaves grow in pairs directly across from one another on opposite sides of the stems. The adult plants of these species are killed outright by fire, and they do not have a burl. The leaves are usually quite thick in these species and are often strongly bicolored, with dark green upper surfaces and pale to white, hairy lower surfaces that may also be dotted with small pits. These leaves may appear to roll up into cylinders and become almost vertical as the environment becomes drier through summer and fall. The stems are a pale gray and have pronounced darker corky bumps just below the leaves. These bumps, technically called stipules, persist on the older twigs and branches so that they may be seen even after the leaves fall off. The function of these structures is unknown (figs. 12, 14).

Plate 38. Chaparral white thorn, a resprouting species of ceanothus, produces abundant clusters of flowers during the spring.

Another highly characteristic feature of nonsprouting species of ceanothus is the braided appearance of the main trunks and stems. This braiding is caused by the death of some parts of the trunks while others remain living and grow around the dead areas. The mix of living and dead areas produces a dimpled or ropy effect. This appearance, called longitudinal bark fissioning, is part of the overall survival strategy of ceanothus. If a root is not in a good location to obtain water, it will die. The part of the stem to which it is connected will also die. Similarly, if a branch is too deeply shaded or otherwise unable to do enough photosynthesis to “pay” for the cost of maintaining it, the branch will die and so too will the root attached to it. The chaparral is a difficult environment for these plants, especially during the dry season, and the only way to survive is to drop the parts that are not cost-effective. The characteristically braided appearance of the stems can still be recognized in the remains of burned stems after fire. While most chaparral shrub species live for great lengths of time, many ceanothus species, especially those that are non-sprouters, appear to have a more limited life span. Places that have not burned in 50 or more years may have more dead than living ceanothus shrubs. Factors contributing to longevity are not well understood. Some of the more commonly encountered nonsprouting members are bigpod ceanothus (C. megacarpus) (pl. 3) and hoaryleaf ceanothus (C. crassifolius) (fig. 14) in southern California, while buck brush (C. cuneatus) (fig. 12) and wavyleaf ceanothus (C. foliosus) are common in the central and northern parts of the state. Members of both subgenera produce seedlings after fire from seeds stored in the soil, but for non-sprouting species, this is the only way to survive. Consequently they are sometimes referred to as “obligate seeders.”

Ceanothus species, both sprouting and nonsprouting, possess an important ability that allows them to grow on particularly poor soils. They are among a special category of plants called nitrogen-fixers. Commercial fertilizers include a healthy dose of nitrogen-containing compounds, and it is the nitrogen that gives fertilizer its strong smell. Inside the roots of ceanothus species, nitrogen from the air is changed chemically into a useful form by bacteria that live within special pockets in the roots, called root nodules. Since these bacteria are housed within the roots, the nitrogen can be pumped directly into the plant as it is produced. The relationship between the bacteria and the ceanothus is mutually beneficial to both species, as the bacteria receive a place to live while the plant receives nitrogen in a useful form. Measurable enrichment of the soil with nutrients such as nitrogen takes years in the stressful environment of the chaparral and is another area of chaparral ecology in need of more study.

Spiny Redberry and Holly-leaf Redberry

Two other buckthorn family members of the chaparral are spiny redberry (Rhamnus crocea) and holly-leaf redberry (R. ilicifolia). Both redberries (fig. 15) are found from the North Coast Ranges to Baja California, usually below 5,000 feet elevation. These shrubs range in height from five to ten feet tall and have shiny, spine-tipped branches and twigs one-half to one inch long. Spiny redberry is most often found where it is sunny, dry, and hot for most of the year and tends to the lower end of leaf size for chaparral plants. Holly-leaf redberry flourishes in moist ravines and shaded locations. Shrubs may be dense with many lateral branches that sometimes retain foliage to the ground level. Flowering occurs in March and April. By the end of spring the shrubs are conspicuously dotted with small, shiny red berries. Both species resprout after fire. Seedlings are most common after fire, but plants may occasionally establish from seed between fires in cleared areas. These two species are very similar in appearance and are sometimes treated as varieties of a single species, rather than as separate species.

California Coffeeberry

A common chaparral shrub in the buckthorn family, California coffeeberry (Rhamnus californica) is named for its red to black fruits, which are the size of coffee beans (pl. 39). This species is widespread and is found from northern California to Baja California in the inland and coastal ranges. Individuals range in height from six to 25 feet tall, growing especially large in moist areas. The elliptical leaves vary from two to five inches in length. In spring and when there is abundant moisture, the leaves are light green, positioned horizontally along the branches, and almost fleshy in comparison with most other chaparral shrub species. These leaves take on a darker appearance during summer and are often vertical and rolled inward on themselves. Clusters of greenish white flowers are found on the shrubs from May through July, producing fruits that ripen in early fall. This species ranges out of the chaparral into evergreen forests and redwood groves. The berries are one of the favored foods of wood rats (Neotoma spp.), and the bases of large old plants are prime locations for wood rat nests.

Figure 15. Spiny redberry, a member of the buckthorn family, derives its name from the many small bright red berries that dot the branches in late spring. The short thornlike twigs and the dense growth form of this species speak eloquently of the difficulty of walking though the chaparral where this species is common. An enlarged flower is shown (lower right).

Plate 39. California coffeeberry takes its name from the resemblance of its fruit to that of ripening coffee. These fruits are a favorite food of wood rats.

The Heath Family (Ericaceae)

The heath family is represented in the California chaparral most abundantly by species of manzanita. This genus (Arctosaphylos) has 60 species, and all but three grow in California. Many are regional endemics restricted to small areas in a particular part of the state, and only a few are widespread. Manzanitas predominate in chaparral from middle to upper elevations, where they are often mixed with chamise, oaks, and conifers (pl. 11, cover photograph). Mission manzanita, summer holly, and Baja California birdbush are manzanita relatives restricted to the southern part of the state and Baja California. Generally, well-known members of the heath family are found in cool, temperate locations in many parts of North America. These include azaleas and rhododendrons, as well as the cultivated blueberry.

Manzanitas

Manzanitas (Arctostaphylos spp.) are the most eye-catching shrubs of the chaparral. Their smooth red brown bark, sculptured trunks, and twisting stems stand out from the dull greens and grays of the other shrubs (pls. 16, 40). Individuals may be tall and statuesque or thicketlike and low growing. It is the taller individuals that generally attract attention. Although the stems are smoothly covered by red bark, the outermost layers of bark continuously peel away in papery curls. These curling pieces are usually visible along the stems.

Like chamise and ceanothus, manzanitas are major components of the chaparral statewide. About half the species occur in northern California and half in southern California, with a few such as greenleaf manzanita (A. patula) growing throughout the state and beyond in the Rocky Mountains. It is not uncommon to find them in the highest elevations where snow is a regular feature of winter and the principal source of precipitation (pl. 13). Like ceanothus, the manzanitas have evolved many species in California, and more than half the species have small natural ranges. Also like ceanothus, there are both sprouting and nonsprouting species, a trait shared only by these two genera among the shrubs of California chaparral. Manzanitas range in size from ankle-high mats to small trees, and across a wide range of elevations from sea level to openings in mountain forests. One species, the bearberry (A. uva-ursi), grows all around the Northern Hemisphere from Siberia to the mountain tops in Central America, and a few other species grow across the American southwest and down into Mexico, but almost all of the others are part of chaparral.

Plate 40. Manzanitas are among the most easily recognized shrubs of the chaparral. On this large individual, gray areas represent portions of the stem and branches that have died, while the red areas represent those areas that are still living.

Manzanitas are among the longest-lived chaparral species, with some resprouters perhaps 1,000 years old! Sometimes the stems have rough gray areas intermingled with areas of smooth red bark. The gray areas are part of the plant that is no longer living. Only the red areas are still alive and growing (pl. 40). This is similar to the pattern in ceanothus species, where parts of the stem die while others remain living. In manzanitas the weaving pattern is in the red stripes along the stem. Stems are often irregular in outline because of this but are not conspicuously braided in appearance as are the stems of ceanothus. The leaves are one to two inches long, elliptical, thick, and typically flat. They are often arranged vertically along the stems. The edges may be bumpy or slightly wavy, and the surfaces vary from bright shiny green to nearly white (pl. 41).

Manzanitas have delicate, urn-shaped flowers that hang upside down on branch tips. Flowers of most species are about the size of a small pea and run from cream colored to pink. The flowering season is primarily during the winter months from December through March. The fruits take months to ripen and may remain hanging on the shrubs for some time. One manzanita plant may produce 100,000 fruits in a season! Because fruit development takes so much energy, manzanita plants usually flower abundantly only every other year. Hanging, spiky clusters of small leaves, called bracts, and undeveloped flower buds form at the ends of the twigs in summer. These structures, called nascent inflorescences, develop for flowering the following year. A close examination of manzanita flower clusters occasionally reveals that some flowers have small holes in the side of the floral tube, near the base (fig. 16). These holes are made by short-tongued insects such as carpenter bees (Xylocopa spp.) that are unable to reach the nectar when approaching from the front, so they alight on the outside of the flower and chew their way in from the outside. These insects do not pollinate the flowers as do the smaller bees that enter the flower from the front, so they are called nectar robbers.

Plate 41. Big-berry manzanita showing the applelike fruits, for which it is named. The fruits turn the same red brown color as the stems when they are fully ripe.

Manzanita fruits have a slightly sweet, leathery outer layer that covers a group of two to 10 hard nutlets that may be fused or separate. The common name is derived from the Spanish word for “little apples,” for the abundant red brown fruits characteristic of this genus. The fruits often ripen like apples, with the side facing the sun turning red first, while the shaded side remains green for a longer period of time. Eventually the fruits uniformly darken to the characteristic red brown color. The genus name Arctostaphylos means “bearberry,” reflecting the importance of the manzanita fruits to both the Black Bear (Ursus americanus) and the extinct California subspecies of the Grizzly Bear (U. arctos). When manzanita fruits are in season the droppings of Black Bears, Coyotes (Canis latrans), and Gray Foxes (Urocyon cinereoargenteus) are often made up entirely of the undigested seeds and papery outer husks of manzanita fruits. The fruits were gathered and consumed fresh by Indians, or dried and stored for later use as a source of flour and for various medicinal purposes. Indians and Spanish settlers made a beverage with the fruits, and Spaniards also used them to prepare a jelly. They were even fermented to make wine. Indians used manzanita branches as construction material, bows, and other hand implements.

Figure 16. Foliage, flower cluster, and fruits of big-berry manzanita. This shrub has smooth, red brown bark and assumes graceful, treelike proportions. The enlarged flower (bottom center) has a hole in it made by a robber bee in search of nectar. The bee is too large to fit inside the flower, so it chews into the flower to steal the nectar, but it does not pollinate the flower.

There are some basic differences in appearances of the sprouting and nonsprouting manzanitas, although they are not split formally into two taxonomic sections, as with ceanothus. The leaves of sprouters and non-sprouters also do not differ markedly; both types have one main vein and hard elliptical leaves. It is necessary to look for the burl in order to confirm the ability to resprout.

Nonsprouting manzanitas, such as big-berry manzanita (A. glauca) of southern California, sticky manzanita (A. viscida) of the Sierra, and Columbia manzanita (A. columbiana) of northern California, have tall trunks sometimes reaching 25 feet or more in height and six to eight inches in diameter. Typically, individuals have one central trunk and rarely develop side shoots at the base. Not all species assume such large proportions, however. The widespread species Mexican manzanita (A. pungens) is a shrub that rarely exceeds six feet in height. In some areas these nonsprouting manzanitas form large pure stands, but they may also be found mixed with other chaparral species such as chamise or ceanothus.

Manzanitas capable of resprouting, such as shaggy bark manzanita (A. tomentosa) (fig. 17) from central California, Eastwood manzanita (A. glandulosa) (fig. 18) of southern California, and the widespread greenleaf manzanita, which grows the length of California, tend to be four to 10 feet tall, with numerous one to two inch stems, and are thicket forming. These species have multiple stems arising from a burl that may become a solid platform after repeated fires. These platform burls may be 25 feet across and weigh over 1,000 pounds. The plant itself is likely to be hundreds of years old. Sprouting manzanita species can form pure stands that cover many acres. As with most of the other chaparral shrubs, however, some species grow in clumps intermixed with oaks (Quercus spp.) or chamise or ceanothus.

Figure 17. Shaggy bark manzanita is found in the central California foothills. The ends of the stems have tiny, leafy inflorescences produced the year before flowering, a feature of this and other manzanitas.

A striking feature of manzanitas is the number of species that are narrow endemics. This is evidenced by species names such as Santa Cruz manzanita (A. andersonii), Vine Hill manzanita (A. densiflora), Little Sur manzanita (A. edmundsii), Morro manzanita (A. morroensis), Otay manzanita (A. otayensis), Pajaro manzanita (A. pajaroensis), La Purissima manzanita (A. purissima), and Refugio manzanita (A. refugioensis). Each of these species is restricted to a small geographical area that is reflected in its common or scientific name. Other species that might appear to be more widespread are actually broken up into small, isolated locations. For example, while Hooker's manzanita (A. hookeri) grows on scattered patches of serpentine soils in central and northern California, it also includes the rarest subspecies in the genus (A. hookeri subsp. ravenii), naturally occurring only inside the Presidio of San Francisco in one small patch that is presumably a clone. Other subspecies are restricted to one canyon or site along a hillside, and several are close to extinction in the wild. The California NDDB classifies 28 taxa of manzanitas as threatened or rare throughout their range; 15 are endangered species, and one subspecies is extinct in the wild. A number of the rarer manzanitas are vulnerable to extinction because of their limited range and the fact that they are on privately held lands that might be developed.

Figure 18. Foliage and fruits of Eastwood manzanita, a common burl-producing species in much of California.

Like ceanothus, hybridization is common between species of manzanita where ranges overlap in naturally occurring populations, and this may have been important in the formation of new species. Manzanita hybrids are produced artificially for landscape plantings, as well. Some rare species have also been introduced to cultivation in an effort to preserve individuals outside of their native habitat.

Mission Manzanita, Summer Holly, and Baja California Birdbush

While many species of manzanita are found throughout California, several of its chaparral relatives have only one species per genus and are restricted to the southern portion of the state. Mission manzanita, summer holly, and Baja California birdbush are similar to manzanita, but each has unique features of flower and fruit that have caused taxonomists to place them in separate genera. That there is only one species in each genus reflects their histories as part of an ancient flora that is now largely extinct; they are the sole survivors of what were once larger groups.

Mission manzanita (Xylococcus bicolor) persists in small populations from western Riverside County south to Baja California, and on Santa Catalina Island. Scattered populations are found in the Verdugo Mountains of Los Angeles County. It bears a strong resemblance to true manzanitas, as it has similar shredding red bark. It is a much-branched shrub six to 15 feet tall. It is easily recognized by its strongly bicolored leaves, dark green on top and white on the underside, with tightly rolled margins, unlike true manzanitas (fig. 19). The rolled margins make the one to 2.5 inch leaves appear narrower than they actually are, an illusion made stronger when they become vertically oriented during the dry season.

Mission manzanita has small, white urn-shaped flowers and red brown fruits much like those of true manzanitas. It flowers in the months of December through February, and the fruits often persist through the summer. This species has a burl and resprouts well after fire. Seedlings are produced only after fire. Visitors to chaparral in San Diego County will be especially likely to encounter this species.

One subspecies of summer holly (Comarostaphylis diversifolia subsp. diversifolia) is found sporadically near the coast in southern California chaparral from Santa Barbara County south into Baja and on the Channel Islands in relict populations. It is often treelike in form and up to 15 feet tall. The leaves are a shiny green, 1.5 to three inches long and about two-thirds as wide, with a finely toothed margin and rolled-under edges. It has a white, urn-shaped flower similar to that of manzanitas, but its fruit is a red, fleshy berry with a solid seed inside. The three largest Channel Islands have the second subspecies of summer holly (C. diversifolia subsp. planifolia), distinguished from its mainland relative by leaf edges that are not rolled under. Flowering occurs in summer after the bloom of most other chaparral shrubs has ended, and as such it is a valuable resource for insects and hummingbirds. This species does not have a burl. Many of the scattered populations of this shrub are being lost to development on private land, and it is classified by the California Native Plant Society as being endangered in part of its range.

Figure 19. Foliage, fruits, and flowers of Mission manzanita, not a true manzanita, although it is in the same plant family. This species is now found only in southern and Baja California.

Baja California birdbush (Ornithostaphylos oppositifolia) is the rarest of these manzanita relatives. It is found in San Diego County and Baja California in scattered locations, many of which are in danger due to loss of habitat as a consequence of development. It resembles summer holly in appearance, although it is generally not as tall. This species is also an important source of food for hummingbirds and insects late in the season.

Madrone, a Nonchaparral Manzanita Relative

In northern California you may occasionally come across a tall, red-barked tree with large, shiny green leaves. This is a relative of manzanita known as madrone or madroño (Arbutus menziesii). This is not a chaparral species, although smaller individuals may be sometimes confused with manzanitas. Madrone occasionally grows in forests or ravines adjoining chaparral areas, for example, in the San Francisco Bay Area. For the most part, madrone is common in oak forest areas and mixed with pines and other cool forest plants as far north as Washington.

Ceanothus and Manzanitas Share an Anomaly

A split in the ability to recover after fire distinguishes ceanothus and manzanitas from all other chaparral shrubs. These genera each include about 30 species that cannot resprout, and a nearly equal number that can resprout. The loss of the ability to resprout is unique to these two genera and suggests that fire has been important in their evolution.

The non-resprouting species produce no burls, and fire kills the adult. Since they cannot resprout, they are replaced in the next generation only by new plants that germinate from seeds. That they do spring forth in great numbers after fire, and only then, is proof that they are well adapted to recurring fire.

Why some manzanitas and some ceanothus, but not all, would lose the ability to resprout is not obvious. One suggestion is that more new genetic variation is produced by starting each generation from seeds rather than from resprouts from an existing burl. Resprouts are simply pruned-back parents, so there is no genetic change after each fire. New and differently adapted offspring produced from seeds are the original and genetically unique products of sexual reproduction. Over time, only those individuals with the traits most suited to the environment would survive and produce offspring, thus tracking the changes in the environment. More work remains to be done to fully understand this phenomenon. In any case, these chaparral genera, with their many resprouting and non-resprouting species, stand in obvious contrast to all the other highly successful chaparral plants—a botanical conundrum.

The proportion of non-resprouting to resprouting manzanita and ceanothus in a given area depends on a complex of environmental variables. For example, whether the percentages of the two types of shrubs will remain nearly equal among ceanothus and manzanita species, as now, depends heavily on fire frequency. This is because all chaparral plants need to grow for several years before they can produce flowers and, from them, viable seeds. For resprouting shrubs, fewer years are required to produce seeds because they can use the root system and energy in the burl to start rebuilding immediately. Still, the newly grown shoots will require a number of years before they have energy to produce a quantity of seeds. After five to seven years, resprouted branches have many leaves with which to make and store energy. At this point, with plenty of energy available, seeds are produced. The non-resprouting shrubs, on the other hand, must themselves begin life from seeds and, at least initially, grow more slowly than a resprout. This is because they do not have the physical head start of roots deep in the soil or stored energy reserves in the burl. It often takes them longer to reach the same size as a resprouting plant and therefore longer to flowering and seed production. Few non-resprouters produce seeds before they are five to 15 years old. Seed production in manzanita increases with age, so 40-year-old shrubs produce more seeds than 20-year-old shrubs, 70- and 100-year-old shrubs produce more than the younger ones. If fires are frequent, for example every two to three years, non-resprouters will be eliminated from that area of chaparral because they simply don't have enough time to make seeds to replace themselves before they are burned up. Resprouting shrubs may continue to resprout after repeated fires at close intervals, but even they need several years in between to recover. If the interval between fires is too short they will be weakened as they repeatedly draw down their reserves. When they fail to grow up to flowering size, no seeds will be produced to replace the parent plant. Frequent repeated fires can eventually eliminate chaparral altogether (chapter 6).

The Oak Family (Fagaceae)

Spanish colonists named chaparral for scrub oaks. The Spanish word chaparra is the name for a shrubby oak that grows in Spain, and its derivative “chaparral” means a place of scrub oaks. Thus, by its very name chaparral signifies the place where scrub oaks grow. This is a fitting description since they are present in nearly all chaparral. Scrub oak is often found mixed with chamise, ceanothus, and manzanita but may form extensive thickets of its own. When a stand of scrub oaks has not burned for several decades, the plants can assume the proportions of a short, compact forest. The stems become thick and twisted, with a dense overhead canopy, beneath which it is sometimes possible to walk. It was this aspect of scrub oaks and other chaparral shrubs that prompted Francis M. Fultz to title the original book about California chaparral The Elfin-Forest of California, a romantic title still used by admirers of chaparral. These oak thickets are among the densest patches within the chaparral and are favored by wood rats for nest building and foraging.

Scrub Oaks

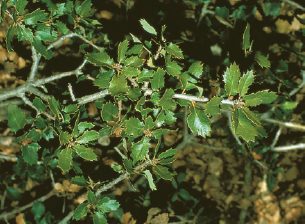

California oaks all belong to the genus Quercus. The distinction between oak trees and scrub oaks is one of stature and form. Scrub oaks are generally less than 12 feet tall and have several to many stems emerging at ground level, while oak trees tend to have a single trunk and be up to 75 feet tall or more. In the chaparral, several species are referred to as scrub oak, the species varying with location and soil type. The most common and widespread is California scrub oak (Q. berberidifolia) (pl. 42). This species is found in the Coast Ranges from far northern California to Baja California, in the foothills of the Sierra, and broadly throughout southern California below 5,000 feet elevation. It may form short, dense shrubs and thickets that range from only a few feet tall to individuals with stems 15 feet or more in height. The flat- to cup-shaped evergreen leaves are .75 to 1.5 inches long. The upper surface is dark green and sometimes dusty looking, while the lower surface is covered by many short hairs and is pale green in color. The margins of the leaves are spiny. New leaves are produced in spring, gradually replacing the old leaves. The leaf litter produced by this annual turnover is deeper beneath oaks than under most other species of chaparral shrubs. Another characteristic feature found on some but not all individuals of scrub oak is the red “apple” galls (pl. 68). These bright red golf ball-sized spheres contrast strongly with the dark green foliage. These structures are caused by a reaction to insect damage to the stem and, although not a fruit at all, look very much like a ripe apple when first produced. They eventually turn brown but are woody and remain on the branches. The relationship between galls and insects is described in more detail in chapter 5.

Plate 42. Scrub oak, with characteristically spiny leaves, has multiple stems that may grow to several inches in diameter. Scrub oak limbs often form the framework for wood rat nests.

Scrub oak flowers are produced between March and May. The brownish green tassels of the male flowers are usually conspicuous due to the large numbers of them dangling below the leaves near the ends of the branches. The small green female flowers, on the other hand, are not obvious. There are many fewer of them and the leaves usually hide them. Once pollinated, acorns, the characteristic fruit of all oaks, begin to form. The acorns have cup-shaped caps with overlapping scales that sometimes appear almost quilted. It is easy to recognize scrub oak by its leaves and by the acorn caps that persist on the branches long after the acorns have fallen. The size of the acorn crop varies between individual plants within a single population and from year to year. Since these large seeds remain on the shrubs for several months, they provide a stable source of food for many species of rodents, birds, and insects. Acorns from several species of California oak trees were a staple food for Native American cultures as well. Among all species of chaparral shrubs, scrub oaks are often the quickest to recover from fire. Plants resprout from the base and occasionally along the thick trunks within days after fire. Seed germination does not require fire, and seedlings can establish at any time. Few seedlings are seen, however, as most acorns are eaten long before the seeds have an opportunity to germinate.

While California scrub oak is the most widely distributed of the scrub oaks, several other species are also found in the chaparral. All of these are similar in appearance to the California scrub oak, making individual descriptions of each species of little value to the average person. A shrub variety of interior live oak (Q. wislizeni var. fructescens) is found in the Coast Ranges in northern and central California through to Baja California. The leather oak (Q. durata) is found on patches of serpentine soils in central and northern California, with one subspecies distributed in occasional places on the south slopes of the San Gabriel Mountains of southern California. Muller's oak (Q. cornelius-mulleri) and Tucker's oak (Q. john-tuckeri) are found along desert borders, in pinyon-juniper woodlands, and in chaparral in southern California. Huckleberry oak (Q. vaccinifolia) forms a low, dense cover in high-elevation chaparral from the central Sierra Nevada north to the Klamath Mountains and the North Coast Ranges. The Brewer oak (Q. garryana var. breweri) forms dense thickets at intermediate elevations in the Tehachapi Mountains, Klamath Mountains, southern Cascade Range, and western Sierra Nevada. Brewer oak is the only California scrub oak that is winter deciduous. Oaks, whether of the shrub or tree type, tend to hybridize readily when they grow together.

Tree Oaks

A number of close relatives of the scrub oaks are trees that are associated with chaparral. The coast live oak (Quercus agrifolia) is the most widespread of these. Its beautiful and familiar form is treasured by many Californians as an emblem of the natural beauty of our state. This evergreen tree is found from northern California to Baja California in valleys, slopes, and canyons, and intergrading with chaparral and woodlands. It tends to grow in places where more water is available, such as north-facing slopes, near canyon bottoms and other drainages, and areas with relatively deep soil. Coast live oaks can become very large (30 to 70 feet tall), living for several centuries and surviving many fires (pl. 43). The trunk may reach several feet in diameter and typically has gray bark that is thick and furrowed. This species has hard evergreen leaves that are somewhat larger, brighter green, and more cupped than scrub oak, with sharp points along the margins. This tree was an important source of acorns to Native Americans in many parts of the state. Several other species of oak trees are similar in appearance to the coast live oak. The most common of these are blue oak (Q. douglasii), a deciduous species with a more northerly distribution that overlaps that of coast live oak and Engelmann oak (Q. engelmannii) in southern California. Canyon live oak (Q. chrysolepis), also known as gold cup oak, is a wide ranging evergreen species that extends into Oregon and Arizona, as well as being found throughout California. Although quite variable in size, it can be distinguished from the other oaks by the gold-colored hairs on the backs of the leaves and on the acorn cups.

Another oak species with a similar distribution to gold cup oak but a very dissimilar appearance is California black oak (Q. kelloggii). It favors stream edges and ravines near chaparral and extends into woodlands and into the higher-elevation coniferous forests. This oak is readily distinguished from the others by the size and shape of its leaves and its deciduous habit. The leaves are much larger and softer than those of the evergreen oaks, 3.5 to eight inches long and divided into wide spine-tipped lobes. In fall, the leaves turn a bright golden yellow before dropping from the tree. The conspicuous display of these yellow leaves when viewed with the blue green chaparral in the background is one of the treats of a fall trip to the mountains.

Plate 43. The coast live oak tree is widely distributed throughout the state. It often grows in flat areas below chaparral, such as shown here, surrounded by naturalized grasses.

Bush Chinquapin

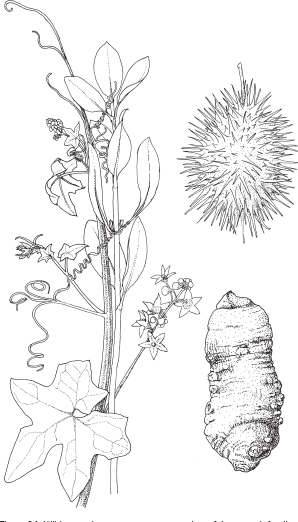

An oak relative, bush chinquapin (Chrysolepis sempervirens), is found in high-elevation chaparral from southern Oregon to southern California. In chaparral it particularly favors rocky areas but is also found in pine forests and alpine areas up to 10,000 feet elevation. Bush chinquapin may reach eight feet in height but is generally about half that tall and grows in dense mounds and forms thick hedges along the roadsides. Bush chinquapin has a conspicuously spiny fruit that is usually produced in small clusters that ripen in fall (fig. 20). The dense form of this shrub and the spiny fruits make it one of the best-defended of the higher-elevation chaparral shrubs. Bush chinquapin sprouts vigorously after fire.

Figure 20. Bush chinquapin, a member of the oak family, is common in high-elevation montane chaparral. The conspicuously spiny fruits persist on the shrub for many months.

The Sumac Family (Anacardiaceae)

The chaparral sumacs belong to a plant family that contains widely differing kinds of plants. For example, the sumac family includes many tropical members such as cashews and mangos and also has some highly toxic plants such as poison oak, poison ivy, and poison sumac. With the exception of poison oak, the chaparral sumacs are restricted to southern California. The typical chaparral species of this region include the laurel sumac, lemonadeberry, and sugar bush. These species are usually found mixed with ceanothus, manzanitas, toyon, chamise, and other species; they rarely grow in pure stands.

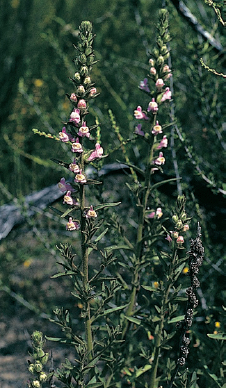

Figure 21. Laurel sumac in flower. One of the common low-elevation chaparral shrubs of southern California, it is not frost tolerant and therefore is excluded from the colder slopes.

Laurel Sumac

Laurel sumac (Malosma laurina) grows on the lower mountain slopes of southern and Baja California. Typically, the plants are tall shrubs reaching to 20 feet in height. The leaves have a very pungent, distinctive odor, particularly in hot weather. The genus name, Malosma, refers to the applelike odor of the leaves when crushed. The leaves are large, four to 10 inches long, and have a characteristically folded appearance, rather like a taco shell (fig. 21). Unlike other chaparral shrubs, the foliage and stems of laurel sumac cannot with-stand a hard freeze. When temperatures remain well below freezing all night long, as happened in southern California for several consecutive nights in the winter of 1989/90, then entire populations of laurel sumac are killed to the base. Recovery from frost damage is quick for laurel sumac, however, as plants resprout from the base of the stems just as they would do after fire (pl. 26), so that within a few years the plants will return to their original stature. The new shoots arise from various points of the root system, and not just from around the base. This pattern of resprouting is different from that of most other chaparral shrubs. In the early years of the southern California citrus industry, before reliable weather records existed for the region, pioneering farmers used laurel sumac as an indicator of places where citrus trees could safely be planted and not killed by frost. Flowers are small, about one-tenth inch across, white, and born in dense pyramidal clusters that are conspicuous in June and July. Fruits are also whitish and small with hard centers.

Lemonadeberry

Another low-elevation, near-coastal sumac is lemonadeberry (Rhus integrifolia) (pl. 34). This species is found below 2,000 feet in southern California, the Channel Islands, and Baja California. It rarely becomes more than four feet tall and is extremely dense and wiry. The dark green leaves are thick and leathery, one to 2.25 inches long and about half as wide, growing shiny with age. They often have a somewhat wavy surface and irregularly spaced teeth along the margins. The lower leaf surface is paler than the upper one, and during the driest times of the year the leaves become vertical in orientation. Lemonadeberry derives its name from the lemony taste of the fruit. When early California settlers mixed the fruit with water, they found that the layer of clear, sugary cells on the outside of the fruit lent a lemony tang to the water. The fruit can also be consumed fresh. Native Americans used the fruit to prepare medicines, and stems were used for a medicinal tea and for basketry. Flowers are pinkish to white in terminal clusters about three inches high. These clusters can be prominent on the shrubs in late winter and early spring because the buds are stout and often crowded. The fruits are approximately one-quarter inch in diameter, reddish, and slightly sticky.

Sugar Bush

At midelevations and interior sites from Santa Barbara to Baja California, and on the Channel Islands, lemonadeberry is replaced by sugar bush (Rhus ovata) (fig. 22). This shrub has multiple, stout twisting stems that may reach 15 feet tall. The shiny, bright green leaves are thick with a smooth margin and pointed tip. They are 1.5 to three inches long and intermediate in shape and texture between those of laurel sumac and lemonadeberry. They are often folded like those of the laurel sumac but, due to the thickness and smaller size, are more open and rounded in appearance. When crushed, the leaves of sugar bush have a pleasant odor somewhat reminiscent of apples, but distinct from the odor of laurel sumac. The year-round dark green, glossy foliage and bright pink clusters of flower buds on outer stems in late winter and early spring make this an attractive shrub that is sometimes cultivated. Sugar bush has fruits similar to those of lemonadeberry, with a covering of crystalline sugary cells, but these fruits were not generally used to make a flavored drink. Sugar bush is larger and more frost tolerant than its more coastal sumac cousins.

Figure 22. Sugar bush with flower buds. This species gets its name from the sugary coating on the ripe fruits. It is a southern California sumac found at mid- to high elevations.

Poison Oak and Skunk Brush: “Leaves of Three, Let It Be”

Poison oak (Toxicodendron diversilobum) is so widespread in California that anyone who spends time in natural plant communities is almost sure to encounter it. In chaparral poison oak grows primarily along trails and canyons and in disturbed areas. Plants may be shrubs or vines and often lean or sprawl onto other plants. Beneath trees such as coast live oak, poison oak can become a heavy vine with thumb- to wrist-sized stems that climb into the treetops (fig. 23). Poison oak prefers cool, moist ravines, north-facing slopes, and canyons but can be found virtually anywhere in California below 5,000 feet.

It is wise to learn to recognize this plant and avoid it whenever possible. It has a three-part leaf with slightly crinkled leaflets one to four inches long. The center leaflet has a short stem and is usually the longest of the three. The new leaves that appear in spring are bright, shiny green and are much larger and softer than those of typical chaparral plants. They are also deciduous. In fall before the leaves are shed, they often turn a bright red (pl. 44). The foliage is attractive and tempting to pick for a fall bouquet. Do not give in to the temptation! Poison oak is so named because touching any part of the plant causes a rash of itchy, oozing blisters for most people. The leaves are typically the source of the rash-causing oil (urushiol). The oil can persist on clothes, sleeping bags, pet fur, boots, skin, and any other surface with which it comes in contact. Touching a contaminated item even after a considerable period of time has passed can result in a new rash. All clothing and other items that may have come in contact with poison oak must be washed thoroughly as soon as possible. Exposed skin should be washed gently (so as not to introduce small cuts) and rinsed thoroughly. A dilute solution of household bleach is sometimes helpful in neutralizing the oil. Never burn poison oak, as the oil is carried in smoke and can cause severe respiratory problems.

Figure 23. Poison oak growing as both a shrub and a thick-stemmed vine; foliage detail in inset. It frequently climbs into oak trees, where it may spread to cover the trunk and main branches, as shown here.

Plate 44. Poison oak can be among the most attractive plants in and near the chaparral when it takes on a bright red color in late summer and fall. Do not touch this plant, however, as the oils it produces can cause a severe skin rash.

Poison oak has a near look-alike, skunk brush or squaw bush (Rhus trilobata). Both plants have soft, deciduous leaves divided into three parts. Skunk brush tends to be a lower-growing plant than poison oak, the stems are usually thinner in diameter and the leaves often hairy, but these differences are subtle and should not be used to distinguish between the two plants by anyone not thoroughly familiar with both. Poison oak has whitish flowers and seeds, while skunk brush has yellowish flowers and reddish fruits. The old warning “leaves of three, let it be” is still good advice. The berries of these species, especially those of the poison oak, are a favorite food of many birds, which spread the seeds to new locations in their droppings.

Other Chaparral Shrubs

California chaparral is characterized throughout much of its range by chamise, and species of ceanothus, manzanitas, and scrub oaks. However, outside of this group, there are other shrubs locally abundant in various parts of the chaparral. For example, coyote brush (Baccharis pilularis, family Asteraceae), also called chaparral broom, is occasionally encountered in and around chaparral (pl. 45, fig. 24). It is found on coastal bluffs and into oak woodlands from Oregon to northern Mexico, in the Sierra foothills and Transverse Ranges, and out to the Channel Islands. This species is highly variable, forming a prostrate mat or an erect shrub up to 15 feet high, or nearly any size and shape in between. The dark green resinous leaves are usually widest at the tip and less than an inch long, with margins that range from smooth to conspicuously notched. The flower heads are small, but usually numerous, in leafy clusters near the ends of the branches. These heads can be seen from a distance because of the protruding short, white to beige tufts of bristles. These bristles serve to disperse the seeds in the air when they are ripe. The chaparral form generally flowers during fall, but as in all other aspects of this plant, flowering time can be highly variable.

Another occasional genus of the chaparral is silk tassel (Garrya spp., family Garryaceae). A half dozen species are common at mid- to high elevations on the dry chaparral slopes in the coastal ranges and the foothills of the Sierra Nevada, and down into southern California. These shrubs are usually less than eight feet tall and silvery gray green with highly reflective stems and leathery vertical leaves. The leaves are in pairs on opposite sides of the stems, 1.5 to 2.5 inches long, with silky hairs that may be straight or wavy. Silk tassels can be locally abundant and are often mixed with manzanitas and other species of chaparral shrubs. Conspicuous features of silk tassel shrubs are the flowers and fruits, which are produced in a dangling, tassel-like bunch from the tips of the branches. Flowering occurs in late winter or early spring, but the dry, pendulous inflorescences may persist on the plant for several months.

Plate 45. Coyote brush, also called chaparral broom, is a common shrub in northern California. Variable in form, it may grow from ground-hugging mat to a shrub well over six feet tall.

A showy shrub to small tree with bright yellow flowers, fremontia (Fremontodendron californicum and F. mexicanum, family Sterculiaceae), also called flannel bush, is sometimes found in chaparral. Fremontia is most common in the mountains of southern California but extends north along the Coast Ranges and the Sierra Nevada on dry granitic slopes. The foliage is rough, hairy, and sandpapery in feel. The leaves range from one to three inches long and may be wider than they are long, especially near the heart-shaped base. They may appear ruffled with deeply grooved veins. The upper surface is usually dark green, with varying numbers of hairs, while the lower surface is densely hairy and white to tawny. The flowers of fremontia are a gorgeous waxy yellow and often about twice the size of the leaves. Flowers may be present from March to June. The fruit has a dense brown covering of short stiff hairs that break off readily and can easily lodge in the fingers.

Figure 24. Coyote brush is often seen with clusters of white-tufted flowering heads along the branch tips contrasting with the green of the foliage. The enlarged leaf shows tiny resinous dots, which cover the leaf surface.