“Oh, no sir, you wouldn’t want The New King James—they merely went through the old King James and changed the thees and thous to yous and thems!” (sic).

The scene was a denominational bookstore in a large and famous U.S. city. The speaker was a saleslady and the would-be NKJV-buyer was a young Bible marketing man who already knew far more than she about the version in question.

Now if the NKJV had been a government project, using public tax money, we could easily believe that over 130 people from all over the English-speaking world might spend seven years and over $4 million and do only as much as the lady suggested. Actually, this was the amount of privately funded time and labor spent in producing the NKJV, which was the fifth major revision of the original Authorized Version in over three hundred years.1 It is an interesting note that the initial translation of 1611 also took seven years to produce.

All of the translators, editors, and reviewers of the NKJV text were competent Christian scholars dedicated to the highest view of biblical inspiration. Also believing in the need for continuity, they were deeply committed to preserving the revered King James tradition for present and future generations of Bible readers. As for the cost, all was provided by Thomas Nelson Publishers, Nashville, Tennessee. Initial funds were made possible by previous sales of a patriotic volume2 celebrating the 200th birthday of the U.S.A.

After struggling with the archaic and obsolete vocabulary and phrasing in the King James Version, young Joe Moore asked his father, President of Thomas Nelson, “Daddy, you make so many Bibles, why can’t you make a Bible that I can understand?” This question was the genesis of the NKJV.

Founded in 1798 in Edinburgh, Thomas Nelson had already pioneered the English Revised Version (1885), the American Standard Version (1901), and the Revised Standard Version (1952). After Mr. Sam Moore bought the company in 1969, he wanted to contribute a Bible that was understandable to young people like Joe and yet retained the great tradition of the Tyndale-King James Bible in text and style.

No easy task!

Across North America and in a few talks abroad it has been my privilege to present the virtues of the NKJV on radio and TV, to pastors, prison workers, Bible people, publishers, churches, para-church societies, colleges, and seminaries. Since so many had a part in this Bible, I trust no one will find it in poor taste for the Executive Editor to draw attention to its qualities. The NKJV is well worth your consideration as your everyday, standard Bible.

Over the years I have sought to reduce my presentation to two main considerations: Readability and Reliability. We will briefly cover the first in this Introduction.

Readability

A great work of literature could conceivably be accurate in its presentation, beautiful in style, complete in text—and yet be unreadable! If my former English literature teachers will forgive my mentioning it, I seem to remember a few very long seventeenth-century poems that fit that very description!

The name “New King James Version” can be stressed on the New part or the King James part. Both are true. If the latter is stressed too much, people get the impression that the NKJV is difficult for most readers (as are earlier editions of the KJV in many places). If we overstress the New aspect, people could get the idea that we have an entirely new version. This is not true. A sufficiently large part of the King James tradition is retained to merit our name. Yet there are enough changes in the work to make it much more readable. But what is “readability”?

Readability is the degree of ease with which printed matter can be read. Tests that measure the reading level of printed matter usually express their results in terms of the public school’s system of grade levels. Thus, material that has a sixth-grade reading level can comfortably be read by a normal sixth-grade pupil.

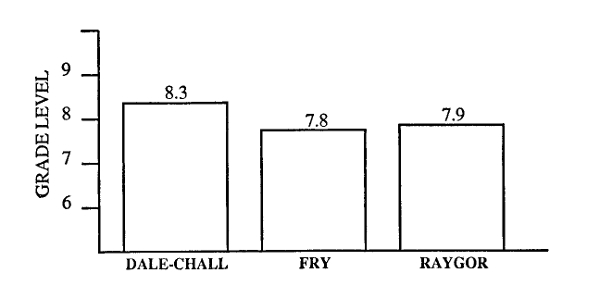

Different readability tests measure different characteristics of reading material. For example, the Dale-Chall Formula counts the number of words in a test passage which do not appear on the Dale list of three thousand words, then combines that information with the number of words and sentences in the passage. The Fry Formula is based on the number of syllables, words, and sentences in the sample. The Raygor Formula is based on the number of words with six or more letters and the number of words and sentences.

We must be careful in measuring the reading level of an English Bible translation because biblical literature is so diverse in kinds of prose and poetry. For its study of reading level, the editors of the New King James Version obtained the services of a specialist in language arts and reading, Dr. Nancy McAleer.3

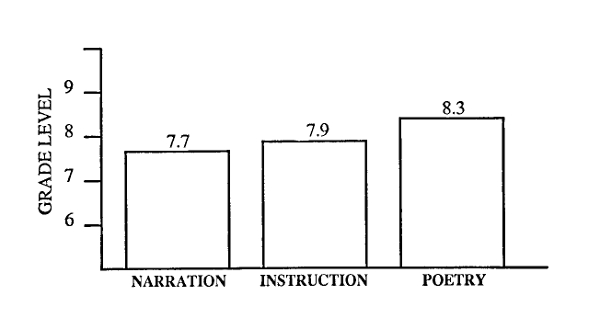

Consideration was given to the different kinds of literature found in the Bible. Two sample passages each were selected from narrative passages, instructive passages, and poetic passages, a total of six test selections. Both Old and New Testament passages were used.

To these six passages were applied three different reading tests: the Dale-Chall Formula, the Fry Formula, and the Raygor Formula. Actual scores on the individual passages ranged from low-fifth grade to mid-tenth grade.

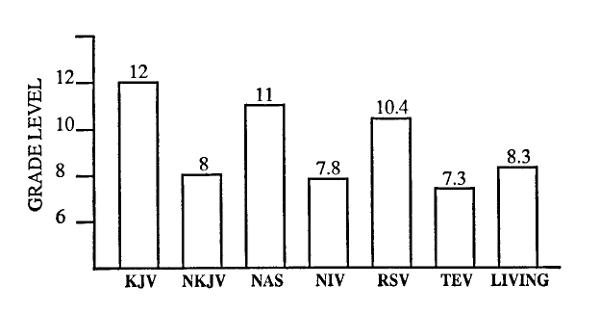

Individual scores were then averaged, and the results were presented in bar graphs. These bar graphs, included here, report in two ways the reading level of the New King James Version. Figure 1 shows the reading level of the New King James Version as measured by each test. Figure 2 illustrates the average reading level of different types of literature in the New King James Version. Figure 3 is a comparison of the reading level of several English versions of the Bible.

As seen by Figures 1 and 2, the reading level of the New King James Version is high-seventh to low-eighth grade.

By comparison, the reading level of samples from a daily newspaper in a U.S. metropolitan area showed a range from eleventh grade to college. Instructions for preparing a TV dinner were written at the eighth-grade level. Directions for taking aspirin were written at the tenth-grade level. The rules for completing a “simplified” income tax form measured above the twelfth-grade level.

Reliability

Conceivably a Bible might be accurate, beautiful, and complete—yet be very hard to read. On the other hand it could be very readable, yet be lacking in accuracy, beauty, or completeness (perhaps all three!). There are such Bibles. A few are published to promote some diluted versions of the Christian faith. The style of some is pretty, but they are also loose and inaccurate. One or two might be correct and yet weak in English style.

The rest of this little volume is intended to show that we didn’t just “change the thees and thous”! The translators, editors, Executive Review Committees, and Overview Committees worked conscientiously together as teams of qualified Christian scholars. They were striving to produce a faithful update of the Tyndale-King James tradition that could truly be considered to possess the ABC’s of good Bible translation:

Accuracy

Beauty

Completeness

These were our goals.

Charts

Figure 1 Reading Level, by Test

Figure 2 Reading Level of Literature Types

Figure 3 Reading Level of English Versions

Notes

1. The Revised Standard Version and the New American Standard Version are revisions, not of the King James, but of the American Standard Version. The ASV was the U.S. variation of the English Revised Version. The ERV was supposed to be a revision of the Authorized Version with only absolutely necessary changes to insure accuracy. (The Old English was retained.) However, the New Testament was translated from the Greek text of Westcott and Hort, not the Textus Receptus of the KJV. Since this departure was not a part of the translators’ assignment, it was criticized—probably rightly so.

2. The Bicentennial Almanac, edited by Calvin D. Linton.

3. Dr. McAleer is the chairwoman of the Department of Education and Human Development, and associate professor at Rollins College, Winter Park, Florida.