No matter how fond of animals you may be, there is nothing heartwarming about the sight of some furry creature munching away on your garden’s bounty. Repellents, traps, and scare devices can help discourage, or fend off, hungry wildlife. But in many cases, especially in rural areas, a fence may be the only effective way to keep marauding mammals away from your landscape plantings and food crops.

The size and type of fence to use depends largely on the kind of animal you’re trying to stave off. A simple 2-foot-high chicken-wire fence will discourage rabbits, but a more formidable barrier is necessary to deal with such garden burglars as deer, raccoons, skunks, or woodchucks.

Cost and appearance are also important considerations. A solid or picket-style wooden fence is attractive but expensive and difficult to install. Wooden fences tend to shade the perimeter of the garden and require regular maintenance. Wire fencing and electric fencing are less costly but are by no means inexpensive, particularly in the case of a large area.

You may be able to forgo fencing off your entire garden or orchard by erecting barriers around only those beds or crops most vulnerable to animal pests. A fenced plot for corn and melons is a good idea where raccoons are a problem. You’ll find more information about making barriers for individual plants, as well as suggestions for using traps and repellants, in the Animal Pests entry.

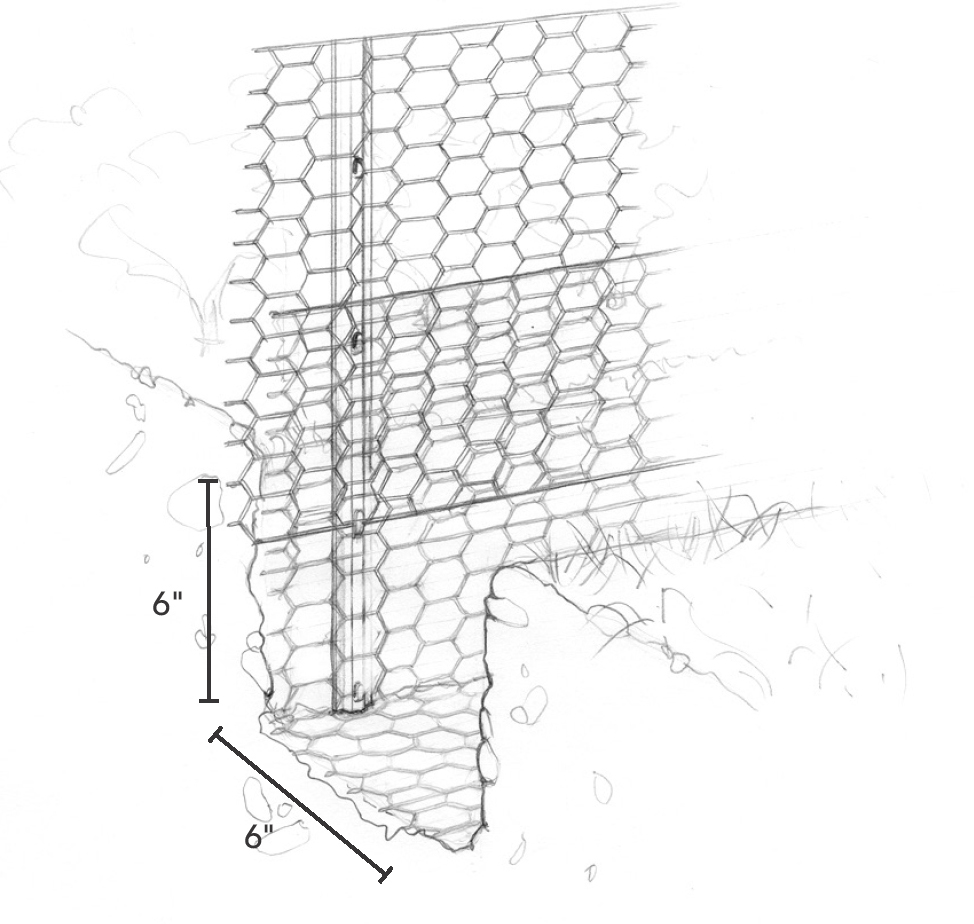

A simple 3-foot-high chicken-wire fence and a subterranean chicken-wire barrier can protect your garden from nearly all small and medium-size animals, including the burrowing types.

Chicken wire comes in a variety of widths and mesh sizes and is sold in 50-foot rolls. The 1-inch mesh is best for excluding animal pests.

Building the fence: The first step in building a fence is to decide where you want it to run. Mark the corners with small stakes and measure the perimeter. You will need two lengths of 1-inch mesh chicken wire, one 3 feet wide for the fence itself, and another 1 foot (or more) wide to line an underground trench. Or purchase one length wide enough to do both.

You also need one 5-foot post for each corner, additional posts for long sections, and one post for each side of the gate(s). Steel T-posts are inexpensive, can be driven into the ground with a hammer or sledge, and come with clips for attaching the fencing. Rot-resistant wooden posts such as locust provide excellent support, but you’ll need a post-hole digger to set them. Also, nailing or stapling fencing to dense wood can be difficult.

Stretch string between the small stakes to mark the fencing line. Dig a trench 6 inches deep and at least 6 inches wide along the outside of the string. Set the posts 2 feet deep along the marked fence line.

Line the trench with the 1-foot-wide chicken wire bent into the shape of an L, so that the wire covers the bottom of the trench as well as the side nearest the fence, as shown. Be sure the wire extends an inch or so above ground level and is securely attached to the posts.

Stretch the 3-foot-wide chicken wire between the posts and attach it to them. The fencing should overlap the chicken wire lining the trench by 2 or 3 inches. Use wire to fasten the two layers together. (If you use a single, wider length of chicken wire, you save this last step.) Then refill the trench with soil.

Altering the design: If woodchucks are a serious problem, make the wire-lined trench a foot or more deep and up to 3 feet wide. If you’re trying to keep gophers out, dig the trench 2 feet deep and 6 inches wide, line it with ¼-inch mesh hardware cloth, and/or fill it with coarse gravel.

Raccoons are good climbers. To foil them, extend the top part of the fence to at least 4 feet, and don’t attach the topmost 1 foot of fencing to the posts. When the burglars clamber up, the loose section will flop backward and keep the raccoons from climbing over the top.

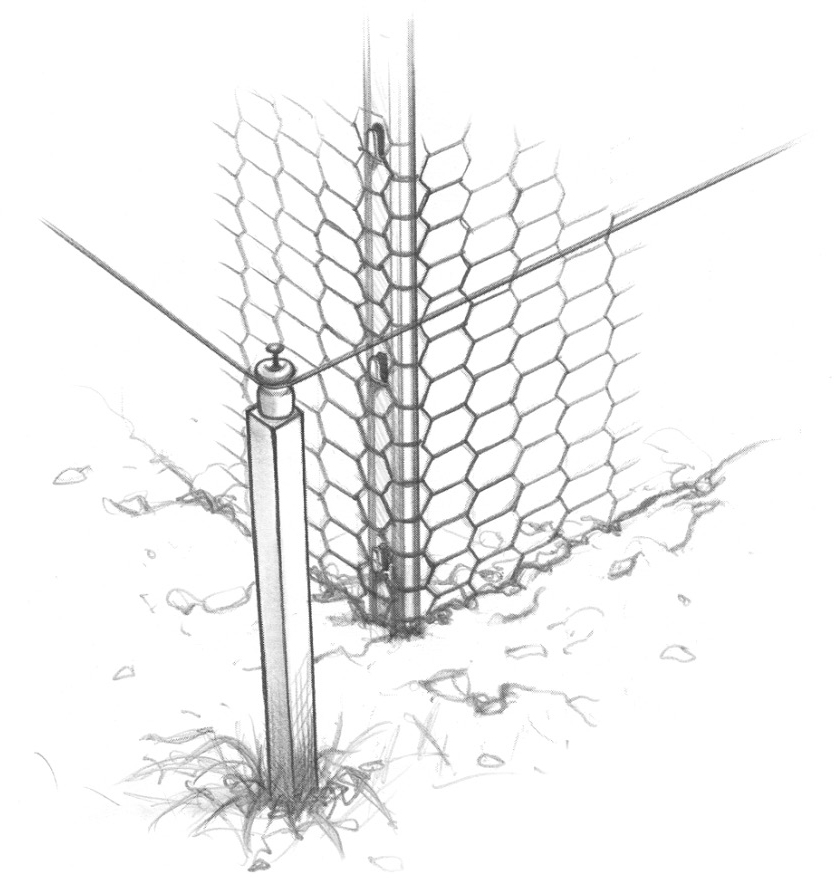

If pests continue to raid your garden despite the chicken-wire barrier, you can add a single-strand electric fence, as shown on the next page.

Most garden supply stores sell easy-to-install electric fence kits, with solar-powered or conventional plug-in battery-powered chargers, 100 feet of wire, and plastic posts. You’ll find a wealth of options on the Internet for purchasing individual components designed with the home gardener in mind.

Chicken-wire fence. A chicken-wire fence supplemented with a 6-inch trench lined with additional chicken wire provides protection against animals that try to burrow underneath fences to raid a garden.

Fencing deer out of a garden requires a more sophisticated approach. A six-strand high-voltage electric fence, with the wires spaced 10 inches apart and the bottom one 8 inches off the ground, is an effective deterrent. But it is an impractical choice for many small-scale growers because of the high cost and complex installation.

Another alternative is to build a fence that is simply too high for a deer to jump over. The absolute minimum height for a jump-proof nonelectric deer fence is 8 feet. Standard woven-wire farm fencing comes 4 feet tall, so it’s a common practice to stack one course on top of another to create an 8-foot fence. This method is neither inexpensive nor easy. Yet another option is weather-resistant polypropylene mesh fencing, which is sold as deer fencing and is available in kits for home garden use. Polypropylene mesh is available in several strengths: Use the highest strength if deer are a problem in your area.

Yet another option is to erect two fences, 3 or 4 feet high and spaced 3 feet apart, of welded-wire or snow fencing. Deer seldom jump a fence when they can see another fence or obstacle just on the other side. If you already have a fence around your garden and deer become a problem, add a 3-foot nonelectric or a 2-foot single-strand electric fence 3 feet outside the existing one.

Animal-proof fence. Adding a low, single-strand electric fence 6 inches outside a nonelectric fence should keep out virtually any animal pest except deer. Set up the electric fence with the wire 4 to 6 inches above ground level.

Ferns are the quintessential shade plants. Their graceful, arching fronds conjure up images of shaded retreats and cool walks by wooded streams. Ferns will grow in the deepest, darkest woodland. They will grow in moist soil and even standing water. However, not all ferns are limited to the shade. Marsh fern, cinnamon fern, and bracken fern grow in full sun. (See “Ferns for Special Uses” for more on this.) But most ferns prefer moist soil and partial shade.

Use large ferns as foundation plantings along with or instead of shrubs. Plant them along fences or walls to break up the flat expanse, or place them to hide the “bare ankles” of sparse shrubs or perennials. Large hostas and ferns will add interest to a shaded spot. Mass plantings of ostrich fern (Matteuccia struthiopteris) and osmundas (Osmunda spp.) are very effective for filling bare spaces or adding depth in the shade of tall trees. They also form a perfect backdrop for annuals and perennials.

Use medium-size ferns such as New York fern (Thelypteris noveboracensis), lady fern (Athyrium filixfemina), and maidenhair fern (Adiantum pedatum) in combination with spring wildflowers. Their unfurling fronds are a beautiful complement to spring beauty (Claytonia virginica), wild blue phlox (Phlox divaricata), and others. Fronds will fill in the blank spots left when wildflowers and spring bulbs go dormant.

Try ferns along the border of a shaded walk to define the path, or ferns with creeping rhizomes on a slope to hold the soil. Mix textures and add evergreen ferns such as wood ferns (Dryopteris spp.) and Christmas ferns (Polystichum acrostichoides) for late-season and winter interest.

Crown-forming ferns like interrupted fern (Osmunda claytoniana) and cinnamon fern (O. cinnamomea) have a graceful vase shape and make excellent accents alone or in small groupings. They grow slowly, so they won’t take over the garden like some running ferns such as eastern hay-scented fern (Dennstaedtia punctilobula). Plant rampant growers where they can spread to form groundcovers and fill in under shrubs. For low, wet areas, chain ferns (Woodwardia spp.), osmundas, and marsh fern (Thelypteris palustris) are stunning. Combine them with the spiky foliage of yellow flags (Iris pseudacorus) and arrowheads (Sagittaria spp.).

Since foliage is the fern’s major attraction, consider the color and texture of the fronds. The most colorful garden fern is the Japanese painted fern, Athyrium niponicum. Its hybrids and cultivars, including the many cultivars of A. n. ‘Pictum’, may have fronds that are gray, blue-gray, gray-green, gray-white, or seemingly variegated with colorful burgundy midribs. (In fact, ‘Pictum’ is considered so outstanding that it was named Perennial Plant of the Year for 2004 by the Perennial Plant Association.) All of these but the gray-green cultivars look great with blue hostas and heucheras with garnet or purple foliage or gray leaves with garnet veining (Heuchera ‘Palace Purple’ is a well-known purple-leaved cultivar). The explosion in heuchera breeding has also produced cultivars with gray-green foliage, some with garnet veining, that combine beautifully with the gray-green cultivars of Japanese painted fern; add green or green and white hostas for textural contrast.

Japanese painted ferns aren’t the only ones that offer color and shine to the shade garden. Chartreuse-colored interrupted fern and maidenhair fern combine well with dark ferns and other foliage. The coppery new fronds of autumn fern (Dryopteris erythrosora) and its orange-red cultivar ‘Brilliance’ add warmth to shady sites and look lovely with chartreuse-leaved hostas, heucheras, and Allegheny foamflowers, as well as heuchera cultivars with coppery foliage. The shiny fronds of ferns such as autumn fern, deer fern (Blechnum spicant), and hart’s-tongue fern (Asplenium scolopendrium) glisten in filtered sunlight.

Ferns generally require rich, moist soil with extra organic matter. Some require a drier, less-fertile soil. If ferns haven’t done well for you in the past, have your soil tested by your local extension service or a soil-testing lab to determine soil fertility and pH. Some ferns are extremely fussy about pH. For more on soils, soil testing, and pH, see the Soil and pH entries.

For large and medium-size ferns, dig the planting area deeply (at the very least, turn the soil to a spade’s depth). Plant smaller ferns such as Japanese painted fern as you would any perennial. Sprinkle on organic fertilizer, if needed, when you add soil amendments. For more on organic fertilizers, see the Fertilizers entry.

Garden centers offer a few ferns, but you can find more through nursery catalogs and Web sites that specialize in perennials, shade plants, or ferns. No matter where you buy, make sure plants are nursery propagated, not collected from the wild. Large plants at low prices usually mean wild-collected plants. Don’t be afraid to ask for the vendor’s sources.

Plant ferns in fall or early spring. Garden-center plants will be potted, but mail-order plants are likely to arrive bareroot. Remove potted plants from their containers, cutting the plastic if necessary. Very carefully score the rootball with a sharp knife. Make three to five shallow cuts lengthwise down the rootball. This breaks up the solid mass of fibrous roots that often forms along the container wall. Plant the fern at the same level at which it was growing in the pot. Planting too deeply will kill plants with single crowns.

Set bareroot plants with creeping rhizomes (underground stems that produce both roots and fronds) ½ to 1 inch below the surface. Large rhizomes can be planted deeper. Set single-crowned ferns like osmundas and ostrich ferns with the crown above soil level. Place the upper part of the rhizome above the soil surface, with the crown 3 to 5 inches above the soil, depending on the plant’s size. Finally, don’t plant too thickly, since most ferns spread rapidly.

Not all ferns are made for the shade—some can take full sun and dry soil. And many ferns are evergreen, enhancing the garden all year. These ferns are all hardy to at least Zone 6; many are hardy to Zone 4, and some to Zone 3.

Ferns for Sunny Sites

Unlike most ferns, deer fern (Blechnum spicant), eastern hay-scented fern (Dennstaedtia punctilobula), fragrant wood fern (Dryopteris fragrans), and sword ferns (Polystichum spp.) can stand at least a half day of sun. For full sun and moist soil, choose water clover (Marsilea quadrifolia), sensitive fern (Onoclea sensibilis), marsh fern (Thelypteris palustris), and chain ferns (Wood-wardia spp.). Ferns that thrive in full sun and dry soil include lip ferns (Cheilanthes spp.), parsley fern (Cryptogramma crispa), polypody ferns (Polypodium spp.), bracken (Pteridium aquilinum), and rusty woodsia (Woodsia ilvensis). You can grow interrupted fern (Osmunda claytoniana) in either full sun and moist soil or shade and dry soil.

Evergreen Ferns

Evergreen ferns add color and structure to the garden all year. The best evergreen choices include spleenworts (Asplenium spp.), grape ferns (Botrychium spp.), parsley fern (Cryptogramma crispa), wood ferns (Dryopteris spp.), hart’s-tongue fern (Asplenium scolopendrium), polypody ferns (Polypodium spp.), sword ferns (Polystichum spp.), and chain ferns (Woodwardia spp.).

Ferns are a carefree group of plants. Mulch with shredded leaves or bark to help control weeds and conserve moisture. Ferns never need staking, pinching, or pruning. You may have to remove an occasional damaged frond, but that—and watering during dry periods while the plants are getting established—about sums up the care requirements for ferns during the growing season.

Each spring, remove last fall’s leaves from the fern bed, shred them, and return them to the bed. Clear the bed early to avoid damage to emerging fiddleheads. Don’t rake the beds, or you may damage crowns and growing tips. You won’t need fertilizer if you leave the mulch to rot into the soil.

For organic gardeners, creating a living soil, rich in humus and nutrients, is the key to growing great fruits and vegetables, abundant flowers, and long-lived ornamental trees and shrubs. The overall fertility and viability of the soil, rather than the application of fertilizers as quick fixes, is at the very heart of organic gardening.

But, like all gardeners, organic gardeners have to start somewhere. Your soil may be deficient in certain nutrients, it may not have excellent soil structure, or its pH may be too high or too low. Unless you’ve lucked into the perfect soil, you’ll have to work to make it ideal for gardening. And even if your soil is rich and fabulous, hungry annual vegetables and flowers need supplemental feeding to produce and look their best. To learn about soil building, turn to the Soil, Organic Matter, and Compost entries. To learn how to use organic fertilizers to feed your plants during the soil-building years, read on here.

Many organic materials serve as both fertilizers and soil conditioners—they feed both soils and plants. This is one of the most important differences between a chemical approach and an organic approach toward soil care and fertilizing. Soluble chemical fertilizers contain mineral salts that plant roots can absorb quickly. However, these salts do not provide a food source for soil microorganisms and earthworms and will even repel earthworms because they acidify the soil. Over time, soils treated only with synthetic chemical fertilizers lose organic matter and the all-important living organisms that help to build healthy soil. As soil structure declines and water-holding capacity diminishes, more and more of the chemical fertilizer applied will leach through the soil. In turn, it will take ever-increasing amounts of chemicals to stimulate plant growth. When you use organic fertilizers, you avoid throwing your soil into this kind of crisis condition.

The manufacturing process of most chemical fertilizers depends on nonrenewable resources, such as coal and natural gas. Others are made by treating rock minerals with acids to make them more soluble. Fortunately, organic fertilizer products made from natural plant and animal materials or from mined rock minerals are gaining widespread acceptance among gardeners and are much more available than they were even 10 years ago. However, the national standards that define and distinguish organic fertilizers from chemical fertilizers are complicated, so it can be hard to be sure that a commercial fertilizer product labeled “organic” truly contains only safe, natural ingredients. When considering options for your garden, look for label terms like “natural organic,” “slow release,” and “low analysis.” Be wary of products claiming to be organic that have an NPK (nitrogen-phosphoruspotassium) ratio that adds up to more than 15. By reading labels and shopping at businesses that offer organic products, you’ll find plenty of products formulated to provide appropriate amounts of the nutrients your plants need while supporting and improving the health of the soil in your garden.

Fertilizers. Materials that feed growing plants.

Soil conditioners. Materials added to feed and enrich the soil.

NPK ratio. The three numbers on a fertilizer label that identify the percentage of three major plant nutrients—nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K)—in that fertilizer.

Top-dress. To apply fertilizer evenly over a field or bed of growing plants.

Side-dress. To apply fertilizer alongside plants growing in rows.

Broadcast. To spread fertilizer evenly across an area, by hand or with a spreading tool.

Foliar feed. To supply nutrients by spraying liquid fertilizer directly on plant foliage.

Leaching. The downward movement or runoff of nutrients dissolved in the soil solution.

If you’re a gardener who’s making the switch from chemical to organic fertilizers, you may be afraid that using organic materials will be more complicated and less convenient than using premixed chemical fertilizers. Not so! Organic fertilizer blends can be just as convenient and effective as blended synthetic fertilizers. You don’t need to custom feed your plants organically unless it’s an activity you enjoy. While some longtime organic gardeners will spread a little bloodmeal around their tomatoes at planting, and then some bonemeal just when the blossoms are about to pop, most gardeners will be satisfied to make one or two applications of general-purpose organic fertilizer throughout the garden during the growing season.

Convenient products like dehydrated organic cow-manure pellets and liquid seaweed make it easy to fertilize houseplants and containers, too. (Don’t use fish emulsion indoors, though, because of its strong odor. Save it for your outdoor containers and garden plants.)

If you want to try a plant-specific approach to fertilizing, you can use a variety of specialty organic fertilizers that are available from Internet garden supply companies or at most well-stocked garden centers and home stores. You can find everything from organic tomato and rose fertilizer mixes to organic fertilizer mixes especially created for transplants, lawns, heavy bloom production, even containers.

You can also make custom mixes to address your plants’ specific needs. For example, you can use bat and bird guano, composted chicken manure, bloodmeal, chicken-feather meal, or fish meal as nitrogen sources. Bonemeal is a good source of phosphorus, and kelp or greensand are organic sources of potassium. The chart on common organic fertilizers lists average nutrient analysis and suggested application rates for the most commonly available organic fertilizers.

Dry organic fertilizers can consist of a single material, such as rock phosphate or kelp (a type of nutrientrich seaweed), or they can be a blend of many ingredients. Almost all organic fertilizers provide a broad array of nutrients, but blends are specially formulated to provide balanced amounts of nitrogen, potassium, and phosphorus, as well as micronutrients. There are many commercial blends, but you can make your own general-purpose fertilizer by mixing individual amendments.

Applying dry fertilizers: The most common way to apply dry fertilizer is to broadcast it and then hoe or rake it into the top 4 to 6 inches of soil. You can add small amounts to planting holes or rows as you plant seeds or transplants. Unlike dry synthetic fertilizers, most organic fertilizers are nonburning and will not harm delicate seedling roots.

During the growing season, boost plant growth by side-dressing dry fertilizers in crop rows or around the drip line of trees or shrubs. It’s best to work side-dressings into the top inch of the soil.

Use liquid fertilizers to give your plants a light nutrient boost or snack every month or even every 2 weeks during the growing season. Simply mix the foliar spray in the tank of a backpack sprayer, and spray all your plants at the same time.

Plants can absorb liquid fertilizers through both their roots and through leaf pores. Foliar feeding can supply nutrients when they are lacking or unavailable in the soil, or when roots are stressed. It is especially effective for giving fast-growing plants like vegetables an extra boost during the growing season. Some foliar fertilizers, such as liquid seaweed (kelp), are rich in micronutrients and growth hormones. These foliar sprays appear to act as catalysts, increasing nutrient uptake by plants. Compost tea and seaweed extract are two common examples of organic foliar fertilizers. See the Compost entry for instructions for making compost tea. Avoid using compost tea made from manure-based composts for foliar feeding of edible crops.

If you want to mix your own general-purpose organic fertilizer, try combining individual amendments in the amounts shown here. Just pick one ingredient from each of the three groups below. Because these amendments may vary in the amount of nutrients they contain, this method won’t give you a mixture with a precise NPK ratio. The ratio will be approximately between 1-2-1 and 4-6-3, with additional insoluble phosphorus and potash. The blend will provide a balanced supply of nutrients that will be steadily available to plants and will encourage soil microorganisms to thrive.

Nitrogen (N)

2 parts bloodmeal

3 parts fish meal

Phosphorus (P)

3 parts bonemeal

6 parts rock phosphate or colloidal phosphate

Potassium (K)

1 part kelp meal

6 parts greensand

Use this table to select the appropriate fertilizers and application rates for your garden. The table lists the NPK ratio, where relevant, as well as the content of other significant nutrients. It also lists the primary benefit of each fertilizer: Some supply particular nutrients, some help balance soil minerals, and others primarily enrich the soil with organic matter.

Use suggested application rates based on your soil’s fertility. If your soil fertility is low, you’ll need to add more of an amendment than you would for medium or adequate fertility. Determine soil fertility with an assessment of your soil by a soil-testing laboratory, as well as your personal observations and the specific requirements of the crops you are growing.

| ORGANIC AMENDMENT | PRIMARY BENEFIT | AVERAGE NPK RATIO OR MINERAL ANALYSIS | AVERAGE APPLICATION RATE PER 1,000 SQ FT | COMMENTS |

| Alfalfa meal | Organic matter | 5-1-2 | Low: 50 lb. Med: 35 lb. Adq: 25 lb. | Contains triaconatol, a natural fatty-acid growth stimulant, plus trace minerals. |

| Bloodmeal | Nitrogen | 11-0-0 | Low: 30 lb. Med. 20 lb. Adq: 10 lb. | — |

| Bonemeal (steamed) | Phosphate | 1-11-0 20% total phosphate 24% calcium | Low: 30 lb. Med: 20 lb. Adq: 10 lb. | Higher grades contain as much as 6-12-0. |

| Coffee grounds | Nitrogen | 2-0.3-0.2 | Incorporate in compost | Acid forming: needs limestone supplement. |

| Colloidal phosphate | Phosphate | 0-2-0 18 to 20% total phosphate 23% calcium | Low: 60 lb. Med: 25 lb. Adq: 10 lb. | — |

| Compost (dry commercial) | Organic matter | 1-1-1 | Low: 200 lb. Med: 100 lb. Adq: 50 lb. | — |

| Compost (homemade) | Organic matter | 0.5-0.5-0.5 to 4-4-4 25% organic matter | Low: 2,000 lb. Med: 1,000 lb. Adq: 400 lb. | — |

| Compost (mushroom) | Organic matter | Variable | Low: 350 lb. Med: 250 lb. Adq: 50 lb. | Ask supplier whether the material contains pesticide residues. |

| Cottonseed meal | Nitrogen | 6-2-1 | Low: 35 lb. Med: 25 lb. Adq: 10 lb. | May contain GMOs or pesticide residues. |

| Eggshells | Calcium | 1.2-0.4-0.1 | Low: 100 lb. Med: 50 lb. Adq: 25 lb. | Contains calcium plus trace minerals. |

| Epsom salts | Balancer, magnesium | 10% magnesium 13% sulfur | Low: 5 lb. Med: 3 lb. Adq: 1 lb. | — |

| Fish emulsion | Nitrogen | 4-1-1 5% sulfur | Low: 2 oz. Med: 1 oz. Adq: 1 oz. | — |

| Fish meal | Nitrogen | 5-3-3 | Low: 30 lb. Med: 20 lb. Adq: 10 lb. | — |

| Granite meal | Potash | 1%–4% total potash | Low: 100 lb. Med: 50 lb. Adq: 25 lb. | Contains 67% silicas and 19 trace minerals. |

| Grass clippings (green) | Organic matter | 0.5-0.2-0.5 | Low: 500 lb. Med: 300 lb. Adq: 200 lb. | — |

| Greensand | Potash | 7% total potash plus 32 trace minerals | Low: 100 lb. Med: 50 lb. Adq: 25 lb. | — |

| Gypsum | Balancer, calcium | 22% calcium 17% sulfur | Low: 40 lb. Med: 20 lb. Adq: 5 lb. | Do not apply if pH is below 5.8. |

| Kelp meal | Potash, trace minerals | 1.0-0.5-2.5 | Low: 20 lb. Med: 10 lb. Adq: 5 lb. | Contains a broad array of vitamins, minerals, and soil-conditioning elements. |

| Limestone, dolomitic | Balancer, calcium, magnesium | 51% calcium carbonate 40% magnesium carbonate | Low: 100 lb. Med: 50 lb. Adq: 25 lb. | — |

| Limestone, calcitic | Balancer, calcium | 65%–80% calcium carbonate 3%–15% magnesium carbonate | Low: 100 lb. Med: 50 lb. Adq: 25 lb. | — |

| Oak leaves | Organic matter | 0.8-0.4-0.1 | Low: 250 lb. Med: 150 lb. Adq: 100 lb. | — |

| Peat moss | Organic matter | pH range 3.0–4.5 | As needed | Use around acid-loving plants. |

| Rock phosphate | Phosphate | 0-3-0 32% total phosphate 32% calcium | Low: 60 lb. Med: 25 lb. Adq: 10 lb. | Contains 11 trace minerals. |

| Sawdust | Organic matter | 0.2-0-0.2 | Low: 250 lb. Med: 150 lb. Adq: 100 lb. | Be sure sawdust is well rotted before incorporating. |

| Soybean meal | Nitrogen | 7.0-0.5-2.3 | Low: 50 lb. Med: 25 lb. Adq: 10 lb. | May contain GMOs. |

| Sul-Po-Mag | Potash, magnesium | 0-0-22 11% magnesium 22% sulfur | Low: 10 lb. Med: 7 lb. Adq: 5 lb. | Do not use with dolomitic limestone; substitute greensand or other potassium source. |

| Wheat straw | Organic matter | 0.7-0.2-1.2 | Low: 250 lb. Med: 150 lb. Adq: 100 lb. | — |

| Wood ashes (leached) | Potash | 0-1.2-2 | Low: 20 lb. Med: 10 lb. Adq: 5 lb. | — |

| Wood ashes (unleached) | Potash | 0-1.5-8 | Low: 10 lb. Med: 5 lb. Adq: 3 lb. | — |

| Worm castings | Organic matter | 0.5-0.5-0.3 | Low: 250 lb. Med: 100 lb. Adq: 50 lb. | Contains 50% organic matter plus 11 trace minerals. |

Source: Reprinted with permission from Necessary Trading Company.

Applying liquid fertilizers: With flowering and fruiting plants, foliar sprays are most useful during critical periods (such as after transplanting or during fruit set) or periods of drought or extreme temperatures. For leaf crops, some suppliers recommend biweekly spraying.

When using liquid fertilizers, always follow label instructions for proper dilution and application methods. You can use a surfactant, such as coconut oil or a mild soap (¼ teaspoon per gallon of spray), to ensure better coverage of the leaves. Otherwise, the spray may bead up on the foliage and you won’t get maximum benefit. Measure the surfactant carefully; if you use too much, it may damage plants. A slightly acid spray mixture is most effective, so check your spray’s pH. Use small amounts of vinegar to lower pH and baking soda to raise it. Aim for a pH of 6.0 to 6.5.

Any sprayer or mister will work, from hand-trigger units to knapsack sprayers. Set your sprayer to emit as fine a spray as possible. Never use a sprayer that has been used to apply herbicides.

The best times to spray are early morning and early evening, when the liquids will be absorbed most quickly and won’t burn foliage. Choose a day when no rain is forecast and temperatures aren’t extreme.

Spray until the liquid drips off the leaves. Concentrate the spray on leaf undersides, where leaf pores are more likely to be open. You can also water in liquid fertilizers around the root zone. A drip irrigation system can carry liquid fertilizers to your plants. Kelp is a better product for this use, as fish emulsion can clog the irrigation emitters.

Growth enhancers are materials that help plants absorb nutrients more effectively from the soil. The most common growth enhancer is kelp (a type of seaweed), which has been used by farmers for centuries.

Kelp is sold as a dried meal or as an extract of the meal in liquid or powdered form. It is totally safe and provides some 60 trace elements that plants need in very small quantities. It also contains growth-promoting hormones and enzymes. These compounds are still not fully understood but are involved in improving a plant’s growing conditions.

Applying growth enhancers: Follow the directions for spraying liquid fertilizers when applying growth enhancers as a foliar spray.

You can also apply kelp extract or meal directly to the soil; soil application will stimulate soil bacteria. This in turn increases fertility through humus formation, aeration, and moisture retention.

Apply 1 to 2 pounds of kelp meal per 100 square feet of garden each spring. Apply kelp extract once a month during the growing season.

If fresh seaweed is available, rinse it to remove the sea salt and spread it over the soil surface in your garden as a mulch, or compost it. Seaweed decays readily because it contains little cellulose.

Ficus carica

Moraceae

If you’d like to try growing an unusual fruit crop that’s delicious and nearly trouble-free, consider figs. These trees will grow well unprotected in Zones 8–10, and also in colder areas if you choose hardier cultivars and give plants proper winter protection.

The Fruit Trees entry covers many aspects of growing tree fruits; refer to it for more information on planting and pruning.

Selecting trees: More than 200 fig cultivars are grown in North America, with a broad range of fruit shapes and colors. It’s important to select a cultivar adapted to your climate, such as ‘Brown Turkey’, ‘Chicago’, or ‘Celeste’ for colder areas. Look for self-pollinating cultivars, as some figs are pollinated by tiny, specialized flies native to the Mediterranean and won’t set fruit without them. (Reputable US nurseries sell only self-pollinating figs.)

Planting and care: Plant as you would any young tree. Figs need a sunny spot that’s protected from winter winds. Mulch trees well with compost, and apply foliar sprays of seaweed extract at least once a month during the growing season.

Container culture: Because figs are tricky to grow in the ground where temperatures drop below 10°F, if you live north of Zone 7 it makes sense to grow your figs in containers. Use a large container (such as a half barrel), preferably plastic to control the weight. Use regular organic potting soil and plant figs at the same depth they grew at the nursery, top-dressing the container with compost. Water when the soil is dry an inch below the surface; if you let containers dry out completely, the figs may lose their leaves. (Leaves will regrow, but it stresses the plant and lessens fruit production.) Set pots in a sunny part of the patio, deck, or yard. You can use foliar sprays or water with liquid seaweed (kelp) or compost or manure tea monthly to give plants a boost.

Pruning and propagation: Use a shovel to disconnect suckers that sprout from the roots throughout the growing season; replant or share them with friends. Figs don’t require formal training; just thin or head back as needed to control size. You can propagate figs by taking cuttings, but the easiest way is to bend a low-growing branch down and secure it to the ground or the soil in a container with a U-shaped wire; cover lightly with soil (and a rock if it resists staying buried) and check for rooting. Once the stem has rooted, sever it from the mother plant with pruning shears and it’s good to go.

Winter care: If temperatures drop to 10°F or colder in your area, and you’re growing cold-hardy figs outdoors in the ground, you can protect them with a cylindrical cage of hardware cloth filled with straw for insulation (don’t cover it with plastic, which can overheat).

Or you can trench the figs each fall and unearth them every spring. To trench plants, prune them back to about 6 feet in late fall and head back any spreading branches. Tie branches with rope or twine to make a tight cylinder. Dig a 2-foot-deep trench as long as the tree is tall, starting at the root-ball of the tree. Place boards on the bottom and sides of the trench. Dig out soil from the roots opposite the trench until the tree is free enough for you to tip it into the trench. Wrap the tree in heavy plastic, bend it into the trench (this will take some effort), and fill around it with straw or dried leaves. Put a board over the tree and shovel soil over the board. Resurrect trees in spring after danger of hard frost is past.

Never try to grow figs in the ground north of Zone 6 (even there, plant the very most cold-tolerant cultivars). Instead, grow your figs in containers and bring them indoors for winter. Keep them in an unheated garage, shed, or other protected area where temperatures don’t dip below 20 degrees. The figs will drop their leaves and go dormant, but you should still water them when the soil dries. Figs will stay green all winter in a greenhouse and may even bear fruit in the warm, sunny greenhouse climate. Make sure you water them regularly, and watch the undersides of leaves for greenhouse pests like aphids. In either case, bring plants back outdoors when the weather warms and the last frost date is past.

Problems: Generally, figs do not suffer from insect or disease problems in North America. Keep birds away with netting; spread wood ashes around the base of trees to keep ants from climbing up to fruits. Keep plants well watered to avoid leaf drop, especially when they’re growing in containers.

Harvesting: In warm climates, you can harvest figs twice—in June and again in late summer. In colder areas, expect one harvest in late summer or fall. Make sure you know the color of your fig’s fruit when it’s ripe. Some figs turn brown when ripe, while others are gold or even green. Check trees daily for ripe fruit in season. Ripe fruits are soft to the touch; skin may begin to split. Figs will keep up to 1 week in the refrigerator, but they spoil easily. Cook figs by simmering them with a dash of lemon and honey for about 20 minutes, mashing them as they cook. Then puree in a food processor, blender, or food mill. The puree freezes well and makes an excellent cookie filling, sauce for ice cream or poached pears, or spread for toast. You can also dry figs in a food dehydrator for nutritious snacks.

For centuries, gardeners have used a variety of techniques to force flowers to open, vegetables to sprout, and fruits to ripen out of season. On the long, dark days of late winter, nothing lifts the spirits as much as the sight of a few branches of golden forsythia or coral-colored flowering quinces (Chaenomeles spp.), or a pot of fragrant purple hyacinths. And if you use row covers or have a home greenhouse, you can extend the harvest period for many fruits and vegetables beyond the usual growing season.

Branches of spring-flowering trees are easy to force for indoor display. You can force almost any spring-blooming tree or shrub from mid-January or early February on. Earlier than this, most forcing fails because buds have not had sufficient chilling to break their natural winter dormancy.

Experiment with a variety of things from your garden, cutting heavily budded branches on a mild day. Select stems of medium thickness or better, since these contain large quantities of stored sugars needed to nourish flower buds. Use a sharp knife or pruning shears to cut the branches; slice diagonally just above a bud. Cut branches at least 2 to 3 feet long; shorter branches are less effective in arrangements. Keep plant health and form in mind as you harvest branches for forcing: Cut as carefully as you would when pruning. To ensure a steady supply of flowers, cut fresh branches every week or so.

After you bring the branches indoors, strip flower buds and small twigs from the bottom few inches of the stems. Slit up the stem ends a few inches or crush slightly with a hammer to encourage water absorption. Some may bloom faster if you submerge them completely in a tepid water bath for a few hours before making your arrangement. Recut stems and change the water in the containers every few days.

Besides forsythias, pussy willows, and fruit trees such as apples, cherries, plums, and almonds, some proven favorites for forcing are flowering quinces (Chaenomeles spp.), lilacs (Syringa spp.), witch hazels (Hamamelis spp.), hawthorns (Crataegus spp.), mock oranges (Philadelphus spp.), spireas (Spiraea spp.), wisterias (Wisteria spp.), spicebush (Lindera benzoin), alders (Alnus spp.), and horse chestnut (Aesculus hippocastanum). Most of these will burst into bloom within 2 to 6 weeks of cutting if forced at temperatures between 60° and 70°F. The closer it is to the plant’s natural blooming period when you cut the branches, the less time it will take for them to open. You can control blooming time to some extent by moving branches to a cooler room to hold them back or placing them in a warm, sunny window to push them ahead.

When arranging forced branches in containers, keep in mind the beauty of stems as well as flowers. Don’t crowd them together so tightly that the intersecting tracery of the branches is obscured.

For more information on forcing, see the Bulbs, Cold Frames, Endive, and Greenhouse Gardening entries.

Forsythia. Deciduous spring-flowering shrubs.

Description: Forsythia × intermedia, border forsythia, grows to 8 feet. It produces bright yellow flowers in early to mid-spring, followed by 3- to 5-inch medium green leaves on arching branches. Often it has good yellow-purple fall foliage color. Zones 4–8.

F. viridissima ‘Bronxensis’, Bronx green-stem forsythia, is a low (10- to 12-inch) groundcover with bright green foliage and primrose-yellow early spring blooms. Zones 5–8.

How to grow: Forsythias grow best in full sun. Provide water in summer to help them get established. Prune after blooming to encourage vigorous growth. Every year, remove about a third of the stems at ground level.

Landscape uses: Use for spring color in a massed planting or as a hedge.

See Digitalis

Fruit trees bloom abundantly in spring, and they’re trimmed with colorful fruit in summer and fall. That makes them a great choice for any home landscape, both for their ornamental value and for the succulent edible treats you’ll harvest. The flavor of tree-ripened apples, peaches, and other fruits is unmatched. And if you check on the prices of organic fruit in your area, you’ll find that growing your own can be a real money saver, too. However, to reap good quality fruit, you must make a commitment to pruning, monitoring, and maintaining your trees.

Before you buy, determine which fruit trees can survive and bear fruit in your climate. You’ll find specific information on climate requirements in the individual fruit tree entries throughout this book (for a list of the fruits covered, refer to the Quick Reference Guide). In general, northern gardeners should choose cultivars that will survive winter cold, blossom late enough to escape late-spring frosts, yet still set and mature fruit before the end of the growing season. Southern gardeners need cultivars that have minimal chilling requirements and that also will tolerate intense summer heat and humidity. For all organic gardeners, choosing cultivars that are disease resistant is especially important. Check with local organic fruit growers or with your local extension office to see which cultivars have a good track record in your area.

Temperature: Many types of fruit trees need a dormant period during which temperatures are below 45°F (tropical fruits are an exception). Without this winter chilling, the trees will not fruit properly. Breeders have developed low-chill cultivars, which flower and fruit with as little as half the usual cold requirement. This allows farmers and gardeners as far south as Texas, northern Florida, and parts of California to grow fruits such as apples, peaches, and pears. Extra-hardy, high-chill cultivars for the far North require longer cold periods and flower a week later than most.

If winter temperatures in your area drop below –25°F, stick with the hardiest apple and pear cultivars; between –20° and 0°F, you can try most apples and pears, sour cherries, European plums, and apricots; if minimum temperatures stay above –5°F, you can consider sweet cherries, Japanese plum, nectarines, and peaches. If minimum temperatures in your area are above 45°F, be sure to choose low-chill cultivars.

Spring frosts: Freezing temperatures can kill fruit blossoms. If you live in an area with unpredictable spring weather and occasional late frosts, look for late-blooming or frost-tolerant cultivars, especially for apricots and plums.

Humidity: In humid regions, select disease-resistant cultivars whenever possible. Diseases that can seriously affect fruits, such as apple scab and brown rot, are more troublesome in humid conditions.

Usefulness: If you are fond of baking, top your backyard fruit tree list with sour cherries and cooking apples, which make excellent pies. For canning, look for suitable cultivars of peaches, nectarines, and pears. For jellies, try apricot, plum, and quince. If you’re interested in fruit for fresh eating, think about how long the fruit will last in storage. Some apples stay good for months if kept cold, but soft fruits must be eaten within about 1 week or they will spoil.

Standard. A full-size fruit tree, usually maturing to at least 20 feet in height, depending on species.

Dwarf and semidwarf. Fruit trees grafted on size-controlling rootstocks. Dwarf trees often mature to 8 to 10 feet in height. Semidwarf trees may reach 12 to 18 feet.

Genetic dwarf. A fruit tree that stays quite small without a dwarfing rootstock.

Rootstock. A cultivar onto which a fruiting cultivar is grafted. Rootstocks are selected for strong, healthy roots, for tolerance of difficult soil conditions, and/or for dwarfing effect.

Whip. A young tree, often the first-year growth from a graft or bud.

Scaffolds. The main structural branches on a fruit tree.

Pome fruit. Fruit that has a core containing many seeds, such as apples and pears.

Stone fruit. Fruit with a single hard pit, such as cherries, plums, and peaches.

Low chill. Requiring fewer hours of cool temperatures to break dormancy.

High chill. Requiring more hours of cool temperatures to break dormancy.

Self-fruitful. A tree that produces pollen that can pollinate its own flowers.

Compatible cultivars. Cultivars that bloom at approximately the same time and can successfully cross-pollinate.

Crotch. The angle of emergence of a branch from the trunk.

Suckers. Shoots that sprout out of or near the base of a tree.

Watersprouts. Upright shoots that sprout from the trunk and main limbs of a tree.

Fruit trees come in shapes and sizes for every yard. Most home gardeners prefer dwarf or semidwarf trees, which fruit at a younger age and are easier to tend.

Standards: Standard apple and pear trees can reach 30 feet or taller, becoming small shade trees that can be underplanted with flowers or ground-covers. They are long lived and hardy but require more space. It can be a challenge to harvest fruit from these trees, too. Standard stone fruit trees can grow quite large as well, but it’s possible to limit their size by training (directing the trees to a particular form), pruning, and limiting fertilizer.

Grafted semidwarfs: Apples grafted on size-controlling rootstocks grow well. However, stone fruit trees grafted onto dwarfing rootstocks often are more difficult to grow well. For more information on the effects of rootstocks on grafted fruit trees, see the Grafting entry.

Genetic dwarfs: Genetic dwarf or miniature trees are naturally compact trees grafted on a standard-size root system. They reach about 7 feet and bear one-fifth as much normal-size fruit as a standard tree. Genetic dwarfs tend to be shorter lived and less winter hardy than standard trees. Northern gardeners may do best growing these dwarf trees in planters and moving them to a protected area, such as an unheated storage room, where temperatures remain between 30° and 45°F in winter. Genetic dwarfs are ideal for the Pacific Northwest or the southern United States. In fact, in those areas they may be preferable to standard trees because they need less winter cold to flower.

Pollination requirements are another important factor to consider when selecting trees. Most apples, pears, sweet cherries, and Japanese plums are not self-fruitful. You must plant a second compatible cultivar nearby to ensure good pollination and fruit set. Peaches, nectarines, tart cherries, and some European plums are self-fruitful. Some cultivars of apples, pears, sweet cherries, and European plums are somewhat self-fruitful but set better crops when cross-pollinated. Refer to individual fruit tree entries for details about pollination requirements. If you lack enough space to plant two fruit trees in your garden, consider coordinating with a neighbor to plant compatible cultivars so you each can enjoy a bountiful harvest.

Plant fruit trees in a small traditional orchard, or intersperse them in borders, mixed beds, or a vegetable garden. You can even put a dwarf apple at the end of a foundation planting. Some will grow in lawns, but most perform better in a prepared bed where they are spared competition from turf grass or other groundcovers.

Be certain the site you choose has the right growing conditions for fruit trees.

Sunlight: Even 1 or 2 hours of daily shade may make fruit smaller and less colorful. Envision the mature size of trees and shrubs close to your planned site. If their shadow will encroach on your fruit trees in years to come, you may want to select a different site. Sour cherries tolerate a bit of shade better than other tree fruits do.

Shaded soil in early spring can be beneficial because cool soil can delay flowering, perhaps until after late killing frosts.

Soil: Fruit trees need well-drained soil. Sandy soils can be too dry to produce a good crop of fruit. Wet, clayey soil encourages various root rots. See “Soil Preparation” to learn how to cope with less-than-ideal soil.

Wind: Blustery winds in open areas or on hilltops can make training difficult, knock fruit off trees early, or topple trees. Staking will help trees resist the force of prevailing winds. Where wind is a problem, you can slow it by erecting a hedge or fence. However, don’t box the tree in and stifle the breeze. Air circulation is helpful for reducing diseases.

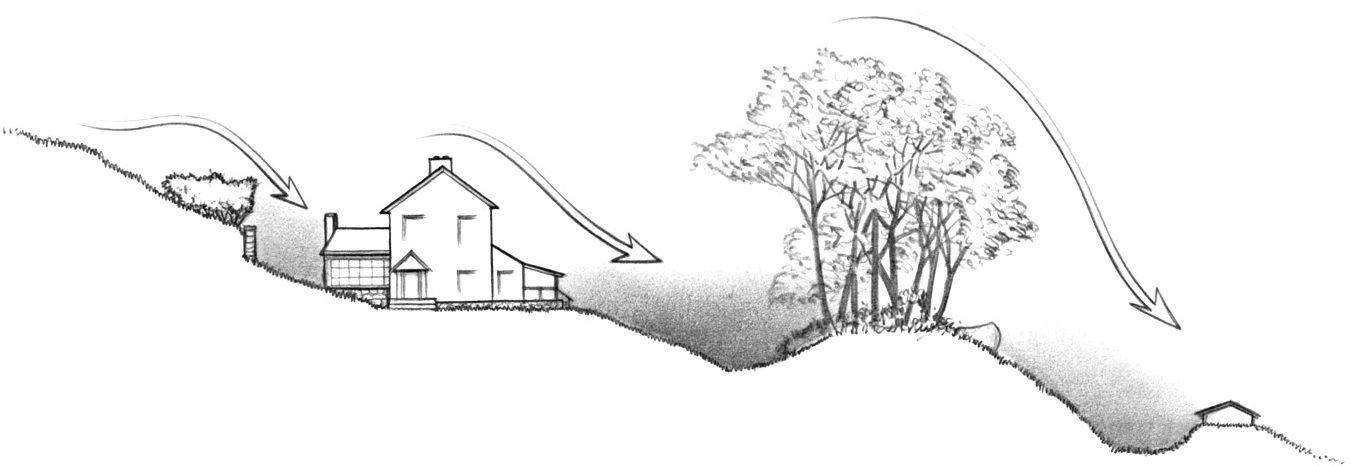

Slope: Plant near the top of a gentle slope if possible. Planting on a north-facing slope or about 15 feet from the north side of a building helps slow flowering in spring and protects blossoms from late frosts. Planting on a south-facing slope can hasten flowering and lead to frost damage. Sheltered alcoves on the south side of a house protect tender trees. Avoid planting in a frost pocket, which is an area at the bottom of a slope where cold air collects, as shown at right. Trees planted in frost pockets have a higher risk of spring frost damage to flowers and young fruit.

The amount of room your trees will need depends on their mature height and width, how they are trained, soil fertility, and tree vigor. Give every tree plenty of space to grow without impinging on neighboring plants or spreading into shady areas. Small trees, such as dwarf peaches and nectarines, require only 12 feet between trees, while standard apple trees need 20 to 30 feet between trees.

To make the effort and expense of planting fruit trees worthwhile and to maximize yield and fruit quality, it pays to prepare the soil properly. Plan ahead, and take these steps in the season preceding the year you plan to plant.

Test the soil and follow recommendations to correct deficiencies. Keep in mind that fruit trees prefer soil high in calcium, magnesium, and potassium, with balanced levels of nitrogen, phosphorus, and micronutrients. Excessive nitrogen can lead to lush growth that is more susceptible to certain insect and disease problems.

Test the soil and follow recommendations to correct deficiencies. Keep in mind that fruit trees prefer soil high in calcium, magnesium, and potassium, with balanced levels of nitrogen, phosphorus, and micronutrients. Excessive nitrogen can lead to lush growth that is more susceptible to certain insect and disease problems.

Raise soil organic matter content by adding compost or planting a green manure crop.

Raise soil organic matter content by adding compost or planting a green manure crop.

Clear out all roots of perennial weeds. To reduce the number of annual weed seeds, lightly cultivate the top 6 inches of soil several times and, if possible, plant a cover crop the season before you plant.

Clear out all roots of perennial weeds. To reduce the number of annual weed seeds, lightly cultivate the top 6 inches of soil several times and, if possible, plant a cover crop the season before you plant.

Amend clayey or sandy soils throughout the area where the roots will extend. A good rule of thumb is to amend the area out to where you estimate the branch tips of the full-grown tree will reach. Add up to 50 percent organic matter, preferably leaf mold and compost. Make a raised growing bed if necessary to improve drainage. Break up any subsoil hardpan and add drainage tiles to eliminate standing water.

Amend clayey or sandy soils throughout the area where the roots will extend. A good rule of thumb is to amend the area out to where you estimate the branch tips of the full-grown tree will reach. Add up to 50 percent organic matter, preferably leaf mold and compost. Make a raised growing bed if necessary to improve drainage. Break up any subsoil hardpan and add drainage tiles to eliminate standing water.

Frost pockets. Cold air collects in a frost pocket at the bottom of a slope. Frost pockets can also occur midslope at a point where buildings, small rises, or trees stop the cold air flow on their uphill side.

If you can’t find the kind of fruit trees you want locally, turn to the Internet or to mail-order catalogs to locate nurseries that specialize in fruit trees, ideally located in a climate similar to your own.

Most of the information you need to make the proper selection, such as chilling requirements and insect and disease resistance, should be listed on the nursery’s Web site or in its catalog. However, you may have to call the nursery to find out what rootstock is used and make your own decision about its compatibility and potential in your area. Also, if the nursery doesn’t list pollination requirements, ask whether a particular cultivar is self-fruitful. If it’s not, ask for names of compatible cultivars.

If you do decide to buy trees at a local garden center, be wary of trees offered in containers. These trees may have been shipped to the garden center bareroot, had their roots trimmed to fit a container, and been potted up just for the sake of appearance. This treatment will not help the tree grow any better, and the stress to the roots may actually set the tree back.

After planting, you can sow annual green manures such as buckwheat beneath the trees. These crops will smother weeds and provide shelter for beneficial insects that help control pest insects. Annual cover crops die with frost and decompose to humus over winter.

Plant fruit trees while dormant in early spring, or in fall where winters are quite mild. Fall planting gives roots a head start, because they continue to grow until the soil freezes. However, fall planting is risky in areas where the soil freezes, because the low temperatures may kill the newly grown roots.

Most nurseries stock bareroot fruit trees. Plant the young trees as you would any bareroot tree. See the Planting entry for full instructions. Set a tree growing on standard roots at the same depth or slightly deeper than it grew at the nursery. If the tree is budded or grafted, set the bud union—the crooked area where the scion and rootstock join—2 inches above soil level. Scions can rot if trees are set too deeply, and the trees can lose rootstock effects.

You may be able to speed a young tree’s establishment by dipping the roots in powdered bonemeal before you plant. Also apply compost tea at planting. See the Compost entry for instructions for making compost tea.

Follow-up care each year is critical to your ultimate goal in planting fruit trees: a harvest of plentiful yields of healthy fruit.

To grow top-quality fruit, and to have easy access for harvesting, you need to establish a sturdy and efficient branching framework. The three main methods for training fruit trees are open center, modified central leader, and central leader. All three systems encourage the growth of branches with wide crotches that are less likely to split when burdened with a heavy fruit load. Which method you use depends on the type of fruit tree and whether it’s a dwarf, semi-dwarf, or standard tree. Ask a knowledgeable local nursery owner or your Cooperative Extension agent which method is best for the trees you plan to grow.

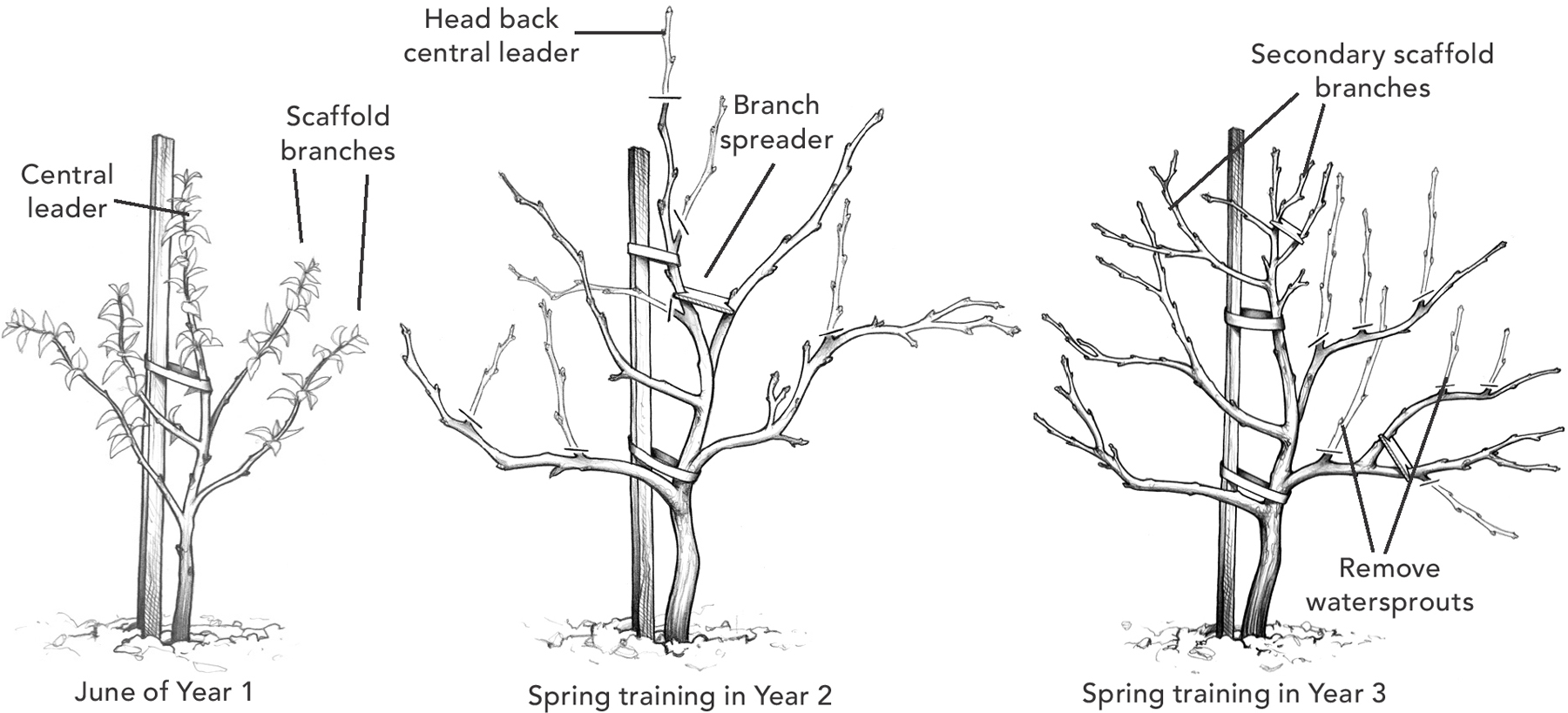

It’s important to establish the main branches while the tree is young. You’ll then maintain tree shape of your bearing trees each year with touch-up pruning. Central leader trees produce more fruiting spurs, important for spur-type apple and pear cultivars. For nectarines, peaches, and Japanese plums, use open center training to maximize air circulation and sunlight penetration among the branches, which will help reduce disease. For instructions on how to make cuts correctly as you train and prune your trees, see the Pruning and Training entry.

Spread young branches so they will develop broad crotch angles. Use clothespins to hold branches out from the trunk, or insert notched boards in the crotch angle. Branches that aren’t spread will be weaker and more likely to break.

In certain circumstances, it’s best not to train. Some fruit trees, including apricots and pears, are particularly susceptible to disease, which can invade through pruning cuts or attack young growth that arises near the cuts. If disease is a problem in your area, you may want to limit pruning to general maintenance or renewal of fruiting wood. In the far North, keep training to a minimum, since new growth is more susceptible to winter injury. However, leave some young suckers on main scaffolds to act as renewal wood in case main branches are injured by cold.

Central leader training: Fol low these instructions and refer to the illustration when training a young fruit tree to a central leader form.

1.Head back a 1-year-old whip to 2½ feet at planting.

2.In mid-June, select four branches that emerge in different directions and are spaced several inches apart along the trunk as scaffolds. The strongest-growing, uppermost shoot will be the central leader, which becomes the trunk. Pinch off all other shoots.

3.For the following few years, repeat this process by heading back the central leader in early spring about 2 feet above the previous set of scaffolds. Then in June, select an additional layer of scaffolds. Choose branches that are at least 1½ feet above the last set of scaffolds. Scaffolds should spiral up the trunk so each branch will be in full sun.

Modified central leader pruning is similar to central leader, but once you’ve trained four or five main scaffold branches, you’ll cut the central leader off just above the highest scaffold branch to open the center of the plant to sunlight.

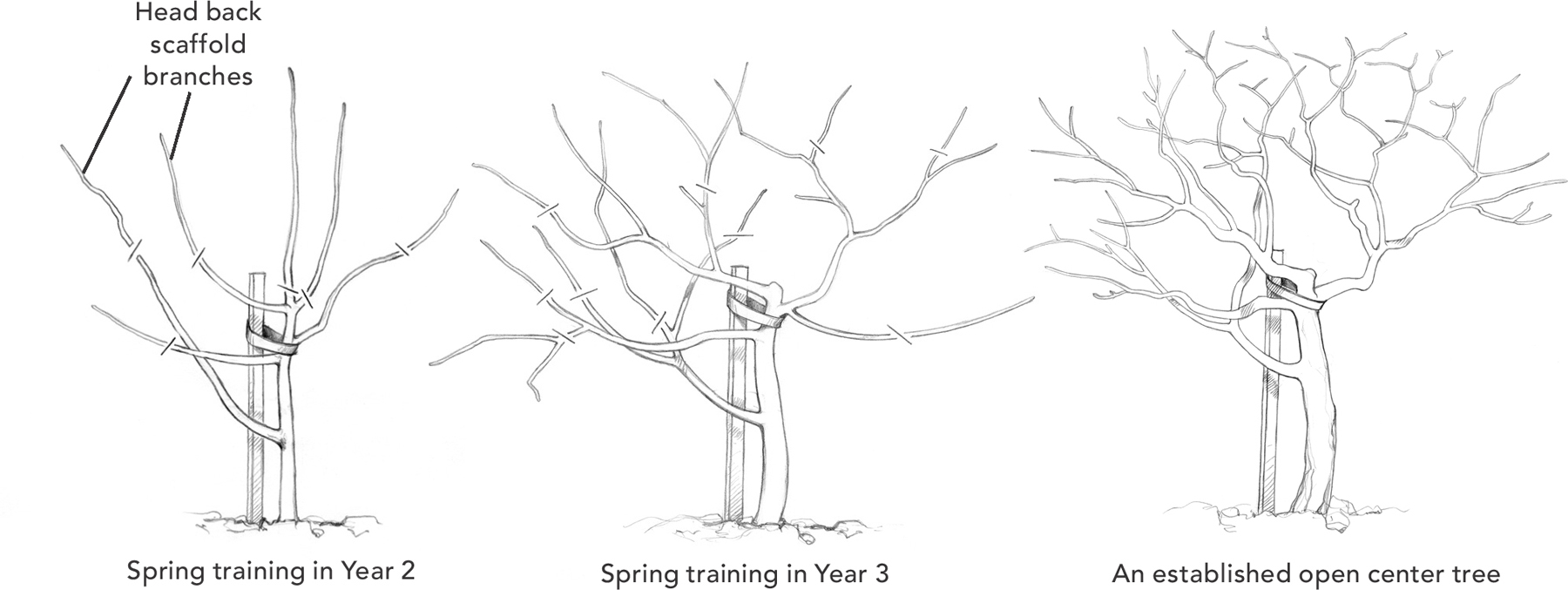

Open center training: Follow these instructions and refer to the illustration when training a young fruit tree to an open center form.

1.Head back a 1-year-old whip to between 2 and 2½ feet.

2.At the beginning of June, choose three scaffolds that emerge in different directions and are separated along the trunk by about 4 inches. Cut off all others.

3.In the third and fourth years, thin as lightly as you can to avoid delaying fruiting.

4.Once peach, nectarine, and Japanese plum trees begin to bear, they fruit only on year-old branches. To ensure plenty of fruiting wood, cut the scaffolds back to the same height every year, encouraging the growth of 1 to 1½ feet of new fruiting wood. Thin overly crowded or short and weak fruiting spurs.

General pruning tips: Whether you train your trees to a specific form or not, it’s a good idea to prune off shoots that emerge low on the trunk and any branches that cross and rub. Where one limb grows above and shades another, or when two branches of equal length and diameter arise at one fork, select one branch to keep and prune off the other. During summer, remove suckers that sprout near the tree base, waterspouts that shoot out from the trunk or main limbs, and any dead or diseased wood.

When to prune varies with the tree type. You can prune apples and pears in early spring before the trees break dormancy. For stone fruits that are susceptible to cankers caused by disease organisms, wait until bud break, when they are less likely to be infected. Prune away dead and diseased branches on all kinds of fruit trees as the growing season continues. Stop pruning by the end of August in areas where winter injury is a concern. Late pruning can stimulate a flush of new growth that could be damaged when cold weather sets in.

Central leader training. This style of training produces a tree with a strong central trunk with scaffold limbs branching off in a spiral pattern. It works well for apples and pears.

Even with thorough advance soil preparation, your fruit trees will benefit from fertilization. Nutrient consumption varies with tree type and age, soil, and growing conditions. For instance, you may have to fertilize a fruit tree growing in your lawn more frequently than if the soil around the tree is cleared and mulched (unless you fertilize your lawn regularly, in which case your trees may receive too much fertilizer). Don’t simply fertilize on a set schedule. Overfertilizing can encourage soft new growth that is susceptible to disease attack and winter injury.

Monitor tree growth to determine when trees need fertilizing. Nonbearing apple trees should grow 1½ to 2 feet per year; those producing fruit average 8 to 12 inches. Mature peach trees should grow 1 to 1½ feet each year. If your tree seems to be lagging, have the nutrient levels in the leaves analyzed. Call your local extension office for information about leaf analysis.

Fertilize only in spring. Spread materials on the soil surface in a circle around the trunk out to the edge of the leafy canopy. If the tree is growing in the lawn, make holes with a crowbar around the perimeter of the branches and drop fertilizer below the grass roots. Avoid high-nitrogen fertilizers. The best fertilizer for fruit trees is compost because it has a good balance of nutrients. Foliar seaweed sprays improve tree health, increase yields, and increase bud frost resistance. Spray trees when buds start to show color, when petals drop, and when fruit is ½ to 1 inch.

Open center training. Trees trained to an open center have a vase- or bowl-like form that lets lots of light and air reach the center of the tree. Use an open center form for nectarines, peaches, and Japanese plums.

Mulched trees will have access to more water and nutrients, especially if you use soil-enriching mulch such as compost or shredded leaves. Mulch will also keep down weeds that compete with trees for water and nutrients. It prevents excessive evaporation of soil moisture, a necessity around young or weak trees, in dry climates, and in sandy soils. In areas with fluctuating winter temperatures, mulch will eliminate damage from frost heaving. Mulch can keep the soil cooler in spring and delay flowering of early-spring bloomers such as apricots or peaches, hopefully beyond the threat of frost.

The drawback of mulching is that it can make heavy soils too wet and can harbor pests, especially mice and voles.

When mulch is needed, apply a 3- to 6-inch layer of organic mulch in an area from 1 to 2 feet away from the trunk out to just beyond the branch tips. Fluff the mulch with a spading fork occasionally so it doesn’t compact. Check the soil moisture level occasionally. If the soil is staying overly wet, rake the mulch back to prevent root rot. Push the mulch out from under the tree boughs during leaf fall so that you can rake up the fallen leaves afterward (this helps prevent disease problems). Afterward, respread the mulch.

Ideally, the soil around fruit trees should be evenly moist, neither dry nor waterlogged. Moisture is especially important to young trees and trees bearing ripening crops. Thoroughly soak the root system of newly planted trees, and repeat whenever the soil becomes dry for the next few months.

After the tree is growing well, your watering schedule will depend on the weather and climate. If the weather has been dry, even during a midwinter warm spell, stick your little finger down in the soil around the drip line. If you do not feel moisture below the surface, water the tree thoroughly. If you have several fruit trees, a drip irrigation system is ideal (see the Drip Irrigation entry). In cold climates, stop watering by early fall to harden the plant for winter.

Protect your trees against winter sunscald, frost heaving, and pest damage, all of which can injure or kill fruit trees. Sunscald occurs when sun-warmed wood is killed by nighttime cold. The damaged area becomes dry, sunken, and attractive to borers and diseases. Prevent sunscald by wrapping the trunk with a white plastic tree guard or painting it up to the first scaffold branch with white latex paint diluted 1:1 with water.

To minimize frost heaving—shifting of soil when it freezes and thaws—apply mulch only after the soil freezes. This is especially important for young trees that can suffer extensive root damage due to frost heaving.

Once your trees reach maturity, there are some extra activities involved in their seasonal care. Some trees may require hand-pollinating, others may need young fruit thinned, and all will have to be harvested.

Hand-pollinating: Early-flowering fruit trees can suffer partial to full crop loss if the weather is not mild when the tree is in bloom. If temperatures aren’t high enough for insect activity, flowers won’t be pollinated and fruit won’t develop. If there’s a cold spell when your trees are blooming, you can save your crop by hand-pollinating. Simply collect pollen from one tree by rubbing flowers gently with an artist’s brush or cotton swab, then brush the pollen onto the flowers of a compatible cultivar.

Be sure nights are frost-free if you plan to hand-pollinate. If you expect a late frost, you can cover small trees with plastic or spray them with a frost-protecting product. As a last resort, try sprinkling water on trees all night. Use care, as the weight of ice that forms on the trees can break branches.

Thinning: Because fruit trees tend to be overburdened by young fruit, it’s important to thin out the excess on all trees except those with cherry-size fruit. Without your intervention, the weight of the fruit may actually break limbs. The stress from the excessive fruit load may also reduce the number of flower buds the tree produces the next year. Disease problems such as brown rot can spread quickly among crowded fruits, ruining the crop before it ripens. In addition to avoiding problems, thinning lets you channel all the tree’s resources into fewer but bigger and more beautiful fruit.

Thin when the fruit is young, the smaller the better. First clip or twist off all insect-damaged or deformed fruits. Then remove the smaller fruits. Leave only the biggest and best.

If you can’t reach the upper limbs of large trees, tap the limbs with a padded pole to shake loose some of the extras. On small apple, nectarine, and peach trees with big fruit, thin fruit to 6 to 8 inches apart. Plums and apricots can be more closely spaced, about 3 to 5 inches apart.

Even after thinning, fruit may become heavy enough to tear a branch. For extra support, prop branches up with a forked stick. On central leader trees, you can secure branches to the central leader with a rope or with a chain covered with garden hose.

Harvesting: Since color is a key indicator of ripeness for most tree fruits, be aware of the ripe color of your trees’ fruits. Most fruit is ready to harvest when the green undercolor changes to yellow or the fruit softens and drops. Grasp the fruit in the palm of your hand and twist it off the stem carefully so you don’t damage the branch. Handle the ripe fruit gently so it does not bruise.

Without regular care, a fruit tree gradually may become overgrown, minimally productive, and home for hordes of pests and diseases. Should you save the old tree or start over with a new one? If the tree has a lovely shape, a vital position in your landscape, or sentimental value, it may be worth keeping. Here’s how to restore it.

•If the tree is suffering from diseases such as scab, black knot, or fire blight, begin a spray program to help lessen damage.

•Remove dead and diseased branches.

•Check for trunk or root rot and, in warm climates, nematodes.

•Prune back any neighboring trees and shrubs that shade the fruit tree.

•Take a leaf analysis for nutrient levels, and correct soil nutrient deficiencies. Use a foliar seaweed spray to restore tree vigor while the soil comes back into balance.

•When the tree is reasonably healthy, you can begin to prune it into a productive shape. Gradually thin out unproductive branches to open the canopy to sunlight. To minimize water-sprout and sucker regeneration, take off no more than one-quarter to one-third of the new wood on the tree or on a particular branch during any one year.

Growing fruit trees using only organic pest control methods requires patience and vigilance. Fruit is so succulent and tasty that it attracts a wide range of pests, from mites to deer. Watch diligently for pests, and control them before they damage the tree or the fruit.

Insects and diseases: Take as many preventive steps as possible to avoid insect and disease problems on your fruit trees. Your best first choice is to plant insect- and disease-resistant cultivars. Pick up and destroy infested or diseased fruit that falls prematurely. Prune out diseased or pest-infested wood.

Learn to identify common pests, and know their life cycles. When pest problems arise, select the most environmentally gentle method of control, such as encouraging or releasing predatory insects. Move on to the use of Bacillus subtilis, horticultural oil, soap sprays, and Bt (Bacillus thuringiensis), depending on the pest you need to control. Reserve botanical insecticides such as neem as a last resort. While they break down rapidly in the environment and are generally less toxic than synthetic chemical pesticides, they should still be used with caution. The Pests entry offers details on control methods.

Animal pests: Deer will eat young shoots, twigs, and fruit. Raccoons will harvest ripe peaches the night before you plan to pick them yourself. Rodents and rabbits will chew on bark during winter. Birds are especially troublesome pests of cherries and plums. For control suggestions, see the Animal Pests entry.

Most fruit trees consist of a preferred fruit-producing cultivar grafted onto the rootstock of a different cultivar. Dwarfing rootstocks are successful for apples and sometimes for stone fruits.

Home gardeners can try their hand at budding or grafting fruit trees. For information on these techniques, see the Budding, Grafting, and Propagation entries. You’ll find recommendations for propagating specific fruits in the individual fruit tree entries.

Pest control is serious business when it comes to fruits. Here you’ll find descriptions of the most persistent tree fruit pests and diseases, the damage they cause, and organic methods you can apply to minimize damage.

| PROBLEM | HOSTS | DAMAGE | CONTROL |

| INSECTS | |||

| Apple maggot (Rhagoletis pomonella) Adults: ¼-inch black flies with yellow legs. Larvae: white maggots. | Apple, blueberry, plum; related flies attack cherry, peach, and walnut. Found in eastern and northwestern United States and Canada. | Larvae tunnel through fruit, which drops early; early cultivars usually most damaged. | Collect and destroy fallen fruit daily; hang baited red sticky ball traps (1–6 per tree), remove traps when fruit colors; cover young fruits with nylon barriers; plant white clover to attract predators. |

| Codling moth (Cydia pomonella) Adults: gray-brown moths, ¾-inch wingspan. Larvae: pink or white caterpillars, brown heads. Eggs: white eggs laid on leaves, twigs, fruit. | Apple, pear. Found throughout North America. | Larvae burrow into fruit. Entry holes are surrounded by dead tissue and sawdust-like material. Fruit interior is dark and rotted. Young fruit may drop. | Sow cover crop to support predators and parasites. Put out 1 codling moth trap per dwarf tree. Cover young fruits with nylon barriers. Spray Bt (Bacillus thuringiensis), starting 15 days after petal fall; repeat 5 and 10 days later. |

| Green fruitworm (Lithophane antennata) Adults: fuzzy-looking gray or purple moths, 1½-inch wingspan. Larvae: light green, with lengthwise stripe on sides, 1 inch. Eggs: tiny, pale gray, sand-dollar-shaped, laid singly on branches. | Apple, apricot, cherry, peach, pear, plum, quince. Found in northern states and southern Canada. | Larvae chew leaves, flower buds, and green fruits. May cause premature fruit drop. Developed fruits show healed-over brown depressions or holes. | Monitor with pheromone traps. Spray Bt (Bacillus thuringiensis) when larvae are feeding. Spray neem for severe infestations. Plant wild carrot and dill to encourage parasitic wasps. These controls are also effective for leaf-rolling pests. |

| European red mite (Panonychus ulmi), other mites Adults: pale brown or reddish, spider-shaped insects, visible with hand lens. Eggs: tiny, reddish, laid in groups around bases of buds and fruit spurs. | Apple, apricot, cherry, peach, pear, plum, quince. Found in most fruit-growing areas of North America. | Heavy infestations cause off-color, bronzed foliage, reduced tree growth, and fewer flower buds the next season. | Plant groundcovers to encourage mite predators. If you’ve had past mite problems, spray dormant oil anytime after buds break until green leaf tips reach ½ inch. Check leaves with hand lens; spray insecticidal soap or horticultural oil if more than 10 mites per leaf. |

| Peach tree borers (Synanthedon exitiosa and S. pictipes) Adults: steel blue, clear-winged moth with yellow or orange markings, 1-inch wingspan. Larvae: white with brown head, 1 inch. Eggs: tiny, brown or gray, laid in bark crevices. | Apricot, cherry, peach, plum. Found throughout North America. | Borers enter bark on lower trunk and injured limbs. Masses of gummy sawdust appear around entrance holes. Branches or whole trees may be stunted and die. | Keep trees healthy and avoid injuring the trunk. If gum appears on trunk (a sign of borer activity), probe holes with wire to kill borers. To kill young larvae before they enter the tree, spray weekly with Bt (Bacillus thuringiensis) from late July until the end of August. |

| Plum curculio (Conotrachelus nenuphar) Adults: gray or brown ⅓-inch beetles with a prominent snout (weevils). Larvae: ½-inch grayish white grubs. Eggs: tiny, white, laid under skin of fruit. | Apple, blueberry, cherry, peach, pear, plum, quince. Found throughout eastern North America. | Small semicircular scars left on green fruit. Larvae burrow and feed on interior of fruit. Fruits drop prematurely. | Collect fallen fruit. Monitor with light green sticky ball traps hung in trees. Knock weevils out of tree onto sheet and destroy. To deter curculios from laying eggs, spray trees with kaolin clay at petal fall and repeat weekly for up to 8 weeks. |

| DISEASES | |||

| Bacterial leaf spot (Xanthomonas arboricola pv. pruni) Overwinters in small cankers in twigs. | Apricot, peach, plum. Common east of the Rocky Mountains. | Many small, dark spots on leaves; centers dry and drop out, leaving shot holes. Small, sunken dark spots or cracks on fruit. | Plant resistant varieties when possible. Fertilize trees as needed to maintain vigorous growth, and prune to improve air circulation. Sprays are not effective against this disease in home orchards. |

| Brown rot (Monilinia fructicola, M. laxa) Overwinters in dried fruit on tree or ground. | Apricot, peach, plum. Found throughout the United States and Canada. | Flowers and new growth wilt and decay. Developing or mature fruit show soft, brown spots that enlarge rapidly and may grow gray mold. | Prune yearly while dormant and also thin branches in midsummer to improve air circulation. Remove and destroy dried fruit, cultivate soil before bloom. Cut out infected twigs. Apply Bacillus subtilis and/or compost tea to help prevent infection. Spray sulfur during bloom and before harvest if weather is humid. |

| Canker, perennial (Leucocytospora cincta, L. leucostoma) Overwinters in cankers and dead wood. | Apricot, cherry, peach, plum. Found in all areas except the western United States. | Sunken, oozing cankers on trunk or twigs. May cause wilting or death of branches or trees. | Avoid mechanical injury. Cut out cankers and dead wood and destroy them. Paint the south side of trunks and large lower branches to prevent winter injury. Apply mulch around trees to reduce water stress. |

| Fire blight (Erwinia amylovora) Overwinters in cankers. | Apple, pear, quince. Found throughout North America. | Young tender shoots die back suddenly. Leaves turn brown or singed looking and remain on the twig. Bark may become water soaked and ooze. | Select resistant cultivars. Cut off blighted twigs at least 8 inches below the infected tissue on a dry day. Sanitize pruning tools between cuts. Limit high-nitrogen fertilizers. |

Fuchsia. All-season tender perennials grown as annuals or houseplants.

Description: Fuchsia × hybrida, hybrid fuchsia, bears distinctive 1- to 3-inch bell- or teardrop-shaped flowers in shades or combinations of white, pink, red, and purple. Blooms seem to dance upon upright or hanging stems ranging from 1 to 5 feet and bearing ¾- to 3-inch green or reddish purple leaves.

How to grow: Plant in the ground or in large pots in partial shade (morning sun is best) and fertile, moist but well-drained, humus-rich soil. Give plants as much root space as possible. Fuchsias dislike hot summers. Water and fertilize often in summer. Before frost, take the plant inside, reduce watering, and allow leaves to drop. Water very lightly until spring, then cut stems back to a few inches. Repot if rootbound, and resume watering.

Landscape uses: Use in hanging baskets, window boxes, or containers. Grow as standards in large pots, trained to a single “trunk.” In Zones 9 and warmer, heat-tolerant fuchsias such as ‘Gartenmeister Bonstedt’, an upright, shrubby cultivar, can be grown outdoors all year. Fuchsias are hummingbird favorites, so add them to a deck or patio to attract these flying jewels to your yard.