I am a content-provider who has been asked by Amy De’Ath and Fred Wah to deliver a statement about my writing practice and what informs it. I receive occasional requests for such statements because some people recognize me as the type of content-provider called a poet. Writing these statements is part of my poetic labour. It is not the norm to be paid for poetic labour. The poetry economy is sometimes regarded as a nonmonetary economy — a gift economy that functions as a source of symbolic or cultural capital while proposing to resist reigning for-profit economies. My own recent experience (which is uncommon, though not at all singular, and not due to any singularity on my part) is that my poetic labour is increasingly monetized.

My present labour will be compensated in the amount of $100 (about $90 US) by the Banff Centre Press. If I read this statement at a poetry reading, I might earn, at a maximum, an additional $150 for the amount of time it would take me to present the present work. I could make a project out of reading it over and over to maximize my ROI, but let’s say I read it once and make $85. Total so far = $175 US; not a huge amount. But my poetic labours also have value for the university where I work. They are deemed valuable regardless of any goals I may have for them; what I say and how I say it matters little as long as the products of my labour are distributed under my name. Mark McGurl elaborates: academic creative writers “contribute a certain form of prestige to the university’s overall portfolio of cultural capital [. . .] testify[ing] to the institution’s systematic hospitality to the excellence of individual self-expression.”1

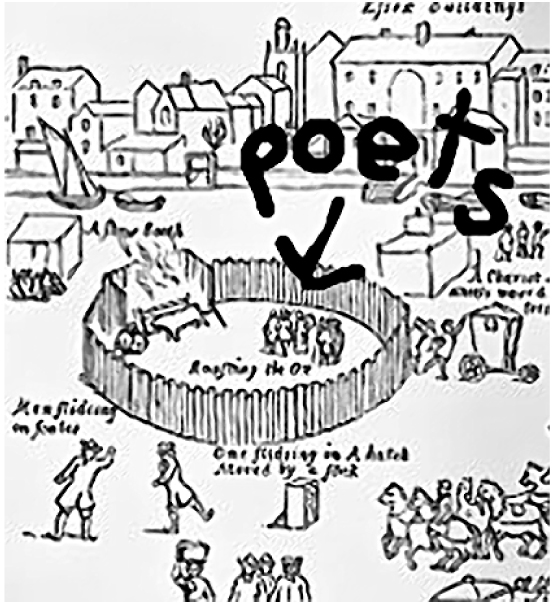

(Dashboard poet)

The achievements and presence of the activist poet-critic Joshua Clover at University of California, Davis contribute to the UC system’s portfolio in spite of or even because of his audacious and thoughtful revolutionary activities. My university (which, like other contemporary institutions of higher learning, is increasingly focused on revenue- and rent-generating programs) compensates me for my poetic labour in various ways. Because my writing is assessed as research at the institution where I work, I will be compensated perhaps $270 US for this piece. I also receive grant funding, travel funding (which permits me the occasional use of a departmental credit card for ticket purchases), health and retirement benefits, and the help of support staff.

(Tenured poet)

My poetic labour is supported indirectly through the office space, computer equipment, electricity, and heating that make my workplace usable and comfortable. Finally, my present labour is an investment of labour capital that could realize a return in future pay raises. This poetics statement could be worth, in time, well over $600 US to me, and perhaps far more; I am grateful to the Academy.

Still, $600 won’t get me very far; I can feel peaceably uncorrupted. Plus, the more I can align my poetry production with the requirements of my institution, the better for both of us, no? That’s the situation I find myself in, striving “[. . .] to unite / My avocation and my vocation / As my two eyes make one in sight.” The proto-neoliberal proposal made in those lines published during another major recession, in 1936, by Robert Frost sums up an apparent win-win for (some) poets in the current market. I feel odd invoking Robert Frost when writing for a presumably avant-leaning poetics anthology, but here goes. “Two Tramps in Mudtime,” the poem I quoted above, tells of two men, recently laid off by the local lumberyard, who interrupt Frost while he’s happily, sweatily chopping wood. The men hope he will yield the labour to them and pay them for it. Frost does not yield it, though he sees their need and understands the logic of their request. When I was a kid I memorized the stentorian final lines of “Two Tramps in Mud Time”:

But yield who will to their separation

My object in living is to unite

My avocation and my vocation

As my two eyes make one in sight.

Only where love and need are one,

And the work is play for mortal stakes,

Is the deed ever really done

For Heaven and the future’s sakes.2

Frost’s defense of the wood-chopping he loves — a job that needs doing, but could be done by others — becomes a defense of his role as poet: I will do this work I love; it must be done, though others may suffer. His grand tone is the inverse of defensiveness, and his defense of what he loves splits him off from others in need.

There is another matter I have not mentioned, another indirect compensation I receive for my poetic labour — not exactly compensation, but “in-kind” funding that gives me time to perform it. I am relieved of teaching one course per year in exchange for my work with graduate students. I gain a bit more time to write, and my writing is informed by the discussions I have with students. I am “relieved” of these courses by academic labourers who make far less than I do: graduate student teaching assistants on small stipends or adjuncts who make $2400 per course without benefits or any assurance of employment beyond the current semester. So part of my poetic labour is dependent on a situation that exploits cheap labour.

One strange thing about getting paid by a university is that it is difficult for me to say anything that would get me fired. For now, it appears that as long as I publish writing in venues deemed sufficiently notable by my dean and provost, I am free, more or less, to speak as I choose, which is a marvel. It is especially a marvel that I can be paid for it. Why then would I worry about the monetization that sustains my life, a monetization that might subtly restrain my imagination, but does not, so far, restrict my activities? Patronage is as old as art-making. To resist its present form suggests a comedy sketch in which I try (or try to look as if I am trying) to smack at a bad baby bottle from which I continue to suckle. The problem is not only the difficulty of locating a fulcrum for resistance to a market-driven system. The problem is that I work in an exploitative system in which freedom is celebrated on the level of rhetoric while the conditions that enable my “free” rhetoric operate by obfuscating exploitation. My writing is a labour of love and someone’s paying for it.

![]()

1 Mark McGurl, The Program Era: Postwar Fiction and the Rise of Creative Writing (Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2009), 408.

2 Robert Frost, “Two Tramps in Mud Time,” in Robert Frost’s Poems (New York: Henry Holt & Co., 1969), 111.