CHAPTER 1

To the City

Under the melodramatic roar of the “El,” encircled by hash-houses and Turkish baths, are the shops of hard-boiled, stalwart men, who shyly admit that they are dottles for love, sentiment, and romance. Apprentices, dodging among the hand-carts that are forever rushing to and from the fur and garment districts, dream of the time when they will have their own commission houses. Greeks and Koreans, confessing that they have the hearts of children, build little Japanese gardens. Greenhouse owners declare that they would not sell—at any price— the flowers which grow in their own backyards. A dealer plans how to improve the business that his grandfather started. And orchids in milk-bottles nod at field-flowers in buckets.

—Jane Butzner, “Flowers Come to Town,” 1937

In 1934, at eighteen, Jane Jacobs (then Jane Butzner) left her hometown of Scranton, Pennsylvania, for New York City, the great metropolis a hundred miles to the southeast, to begin her career as a writer. Although she did not start writing her best-known book for another two and a half decades, moving to New York was the beginning of The Death and Life of Great American Cities, which she later dedicated “TO NEW YORK CITY.” Without Jacobs’s experiences there, it is difficult to imagine her writing Death and Life and many of the books that followed.1

Cities, as Jacobs later described them in Death and Life—where she typically resisted figurative language despite her early interest in poetry— were lights in the darkness. Although mindful of the analogical fetishes frequent among theorists of architecture and cities, and believing that a city could be best understood “in its own terms, rather than in terms of some other kinds of organisms or objects,” she could not resist an analogy here. Imagine, she told her readers, a large, dark field, where “many fires are burning. They are of many sizes, some great, others small; some far apart, others dotted close together; some are brightening, some are slowly going out. Each fire, large or small, extends its radiance into the surrounding murk, and thus it carves out a space.” Cities were light and life, and New York was the great fire in the darkness. “Life attracts life,” she wrote in Death and Life. The aphorism, although she did not relate it in the book to her personal experiences, was rooted in her biography: Jacobs understood the attractive powers of great cities from an early age.2

Changing rapidly, New York was also the best of places, and the 1930s were perhaps the best of times, to observe great American city dynamics at work. On its way to becoming the greatest of American cities and one of the greatest of the world’s great cities, New York was The City for many Americans and immigrants, and Jacobs was one of them. In 1935, Berenice Abbott, who later became Jacobs’s friend, described her Changing New York photographic exhibition as witnessing “the end of something.” It was the end of premodern New York.3

Consolidated in 1898 and home to the world’s tallest building by 1913, New York City had a population that doubled from approximately three and a half to seven million people between 1900 and 1935. Housing shortages and traffic congestion were already problems; slum clearance housing projects and, by the mid-1920s, highway projects were deemed necessary. Only sixteen years after Henry Ford’s Model T automobile came to market, in the 1924 New York Times article “New York of the Future: A Titan City,” the city’s police commissioner called for the building of elevated highways: “Commissioner Enright has announced his conclusion that New York is already at the saturation point. Already the motor car, designed to accelerate movement, has by its very multiplicity defeated itself. Consequently the traffic officer has become the town planner.” The same article compared New York to Chicago, where “deep in the heart of the town, tenements are being torn down to make way for spacious new thoroughfares.” What of New York? “While Chicago talks of its conception of a ‘city beautiful’ and works prodigiously, has New York, the greater city, no far-flung plans?” Was it “timid in the face of imperial ideas, parsimonious at the thought of vast public expenditures?” The answer was no, it was not. New York would not be bested.4

FIGURE 2. Oak and New Chambers streets, Lower East Side, as captured in 1935 as part of Berenice Abbott’s Changing New York WPA photography project. The area was destroyed in 1959 for an expansion of the adjacent civic center. New York Public Library.

By 1935, when Jacobs published her first writing on the city, New York was recovering from the Great Depression and determined to shed the trappings of the nineteenth century. Historically, the city was organized in a tight pedestrian neighborhood pattern of what later became called “Jane Jacobs blocks”—where all daily needs could be satisfied by walking one or two self-sufficient blocks containing a grocery store, barbershop, newsstand, butcher, drugstore, deli, laundry, flower shop, cobbler, stationer, bar, hardware store, bakery, and so on. “So complete is each neighborhood, and so strong the sense of neighborhood, that many a New Yorker spends a lifetime within the confines of an area smaller than a country village,” wrote E. B. White in Here Is New York in 1949. “Let him walk two blocks from his corner and he is in a strange land and will feel uneasy till he gets back.”5

Yet, prompted by new building techniques and means of transportation, the time was ripe to think about the “modern” city—for new ideas about city planning and civic art, land use, building and rebuilding, rapid transit and highways, housing and new communities, parks and open space, and skyscrapers. As the authors of the Regional Plan of New York and Its Environs observed in 1929, “In spite of the great changes that have come over cities in connection with the development of vehicular transportation and steel construction, and of the imminence of new changes as a result of the development of the airplane, much of what may be called ‘medievalism’ persists in the modern city.” “Skyscrapers are as modern as the motor car. Their influence has been great but has really only begun to be felt,” they predicted. Land use needed to be reconsidered to provide skyscrapers with appropriate breathing room. “The skyscraper mountains enclose working places that are little better lighted and ventilated than mines. … Why can we not have the skyscraper and still get sufficient daylight for it and other buildings?” they asked. Modern architects like Le Corbusier certainly agreed. But Le Corbusier, who visited New York in 1935, and experienced firsthand the city so frequently referenced as an inspiration and counterexample in his City of To-Morrow and Its Planning (1929), was not alone. A city organized to provide its residents with sunlight, fresh air, green spaces, decent housing, and ease of movement seemed only natural and common sense.6

Indeed, many of the goals and ambitions of postwar urban renewal were established in the 1930s. The decade epitomized the “creative destruction” of Manhattan and anticipated the urban renewal era of the 1950s and 1960s. Apart from the construction of highways and parkways that sought to reduce congestion and traffic fatalities and make new commuter suburbs accessible, the first public housing project in the United States, First Houses, was dedicated on December 3, 1935, by First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. Modest but expensive, it was a housing experiment clearly inadequate as a model for growing housing needs. With New York’s population growth showing no signs of slowing, the plans on drawing boards were ever more ambitious. Thus, while visionaries and reformers like Le Corbusier and the writer Lewis Mumford imagined more humane “Radiant Cities” and “Garden Cities,” the problem of quickly supplying a huge number of dwellings, and making them affordable, resulted in designs that privileged quantity over quality. The “pathology of public housing,” which Jacobs would observe in East Harlem two decades later, had its roots during this period.7

FIGURE 3. A conception of the modern city with “proper restraint of height and density of building, together with well balanced distribution of ground space, overground space above lower buildings and occasional high towers,” and a “sunken road for fast vehicular traffic.” Thomas Adams et al., The Building of the City, Regional Plan of New York and Its Environs, vol. 2 (Philadelphia: William F. Fell, 1931). Rendering by Maxwell Fry.

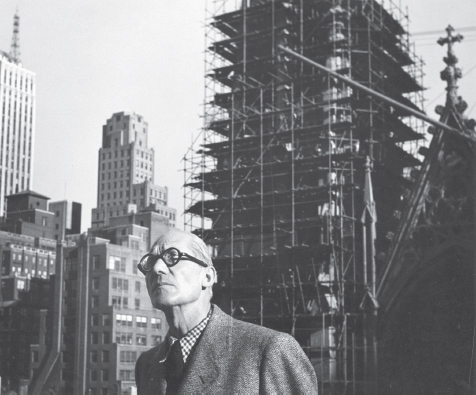

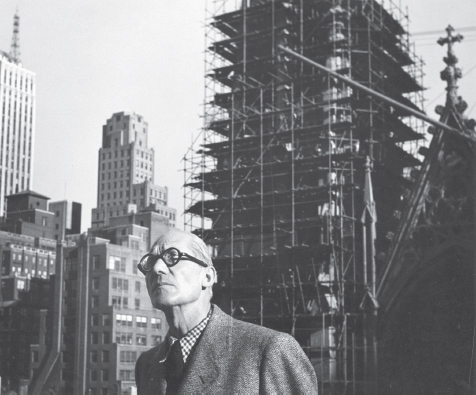

FIGURE 4. Le Corbusier in New York, 1935. Getty Images.

In the meantime, Jacobs’s thesis of city “death and life” was also evolving. From 1935, Jacobs’s earliest writing on the city reveals that she understood that cities and their neighborhoods changed over time, declining and regenerating. “Unslumming and Slumming,” the title of Death and Life’s fifteenth chapter, described this urban dynamic from the point of view of human geography and the self-regeneration of neighborhoods. It was, in part, a personal story. Describing Greenwich Village, where she made her home soon after moving to New York, as an “unslummed former slum” in Death and Life, Jacobs recognized herself as having participated in the spontaneous and historic processes of city decline and regeneration that were of central importance to the book and to her understanding of cities.8

Seeking Her Fortune

Viewed from the dark hills of northeastern Pennsylvania, New York City was a great bright light on the horizon. While Scranton’s economic lights had started flickering amid the increasing turbulence of competition in its coal and steel industries before the Great Depression, New York grew into a great city. The sparkle of New York’s ebullient Jazz Age had dimmed but was not out: The recently completed Chrysler and Empire State buildings were shiny and new, even if largely vacant, and Rockefeller Center, where Jane Jacobs would later work, was pushing rapidly skyward. With a similar resolve, Jacobs later stated, “I came to New York to seek my fortune, Depression or no.”9

By moving to a great city when she came of age, from a place with fewer opportunities to one where she could experience the richness of city life, Jacobs participated in not only a universal human tradition, but also one familiar in her family. Her mother, Bess Robinson, a nurse who grew up in a small Pennsylvania town, and her father, John Butzner, a doctor who grew up on a Virginia farm, had met in Philadelphia, where they studied and worked before moving to Scranton. Both found city life superior to rural life, and they shared their experiences with Jane and her three siblings (Elizabeth, James, and John), understanding their children’s desires and perhaps need to move from Scranton to pursue their livelihoods. Jane’s older sister, Betty, who had studied interior design in Philadelphia, had already settled in New York.10

In her youth, Jane had decided to pursue a career as a writer. Around the age of eleven, she became serious about poetry and quickly discovered the satisfaction and praise of publication for pieces first published in a local newspaper and in the Girl Scouts’ widely circulated American Girl magazine in 1927. Although her interest in creative writing continued into adulthood (she continued to write poetry and tried fiction in the mid-1950s, just before becoming significantly involved in urban renewal controversies), her focus turned to nonfiction in high school.

Following graduation from Scranton’s Central High School in early 1933 and a subsequent training course in stenography at Powell Business School, she was “thoroughly sick of attending school and eager to get a job, writing or reporting,” as she described that time in her life in a rare autobiography. In August 1933, she found a job with the Scranton Republican, and, until the newspaper was sold to the Scranton Tribune in June 1934, Jacobs worked as an assistant to the society editor but soon took on the responsibilities of assistant editor, covering events like civic meetings and arts reviews, and laying out the Society page, a task previously left to the composing room foreman but later adopted by other departments of the paper. On her own initiative, she assumed the role of cub reporter, seeking out and developing her own feature stories for the city desk.11

Laid off from the newspaper and still too young to move away from home, Jacobs spent six months, between May and November 1934, with an aunt who directed a Presbyterian mission in Higgins, North Carolina, a hamlet that was a pinprick of light barely illuminating the darkness of the Appalachian Mountains. Her experience there, referenced directly and indirectly in her books decades later, made a deep impression. As she later explained in Cities and the Wealth of Nations, Higgins (which she called Henry in the book) had been dying for over a century, all but cut off from the economies of cities for about a century and a half. Becoming increasingly isolated, the settlement, she wrote, “proceeded to shed and lose traditional practices and skills after it had lost almost all contact and interchange with the economies of cities,” eventually reverting to a subsistence economy. In a notable anecdote, Jacobs recounted how her aunt’s parishioners had argued against building a church made of stone, despite being surrounded by Blue Ridge Mountain granite. According to Jacobs, the townspeople had lost both the masonry skills and ambitions of their forbears, who had built stone parish churches, even great cathedrals, from time immemorial. “Having lost the practice of construction with stone, people had lost the memory of it, too, over the generations,” she wrote, “and having lost the memory, lost the belief in the possibility—until a mason arrived from the nearest city, Asheville, and got them started on a church of small stones.” The anecdote was meant to exemplify how cities, as dense repositories of culture, perpetuated even those practices typically considered innately rural.12

Regardless of why Higgins’s townfolk may have opposed building a stone church, Jacobs’s experiences there were fresh in her mind weeks later, when she arrived at her sister’s apartment in Brooklyn in November 1934. The contrast, of course, could not have been greater. While the people of Higgins, surrounded by stone, apparently found the prospect of building a small stone church daunting, in New York one of the largest private building projects in modern times, Rockefeller Center, clearly showed that a great city could withstand even a great economic depression. Although Jane would struggle to find any work, and she and Betty would be reduced to eating baby cereal, the cheapest food they could find, by the end of 1934, New York had seen the worst of the Depression and there was a sense of cautious optimism in the air. The Central Park “Hooverville” was gone, and Franklin Delano Roosevelt was promising the American people a “New Deal.” New York, offering promise for the nation at large, suggested that robust cities would not succumb to Higgins’s fate.

FIGURE 5. Jane Jacobs’s high school graduation photo, January 1933. Jacobs Papers.

Unable to find a position with a magazine or newspaper, Jacobs looked for part-time work and freelance writing opportunities. She made the most of job hunting, which turned out to be a good way to get to know the city’s neighborhoods and business districts. From her first New York home, a six-story walkup on Brooklyn’s Orange Street (later destroyed by the Cadman Plaza renewal project), and later from Greenwich Village, where she and Betty moved in October 1935, Jacobs explored Manhattan as she answered want ads, sometimes getting off the subway at random stops for the surprise of discovering the marvels of the city, which inspired her to continue her poetry writing. In this way she discovered the working districts of the city, whose vitality, largely undiminished by the economic situation, afforded her some employment and whose energy and complexity captured her imagination after her time in Appalachia.13

Jacobs would spend most of the years from 1935 to 1938, when she started college at Columbia University, in Manhattan’s working districts, employed as a secretary at various New York manufacturing businesses. Her writing career would not be delayed, however. In 1935 and 1936, at New York University, she took three journalism courses on newspaper feature writing, editorial writing, and magazine article writing. And her first job was working as an assistant to a writer, soon followed by the development of her own writing projects, a preoccupation that led to her first essays on the city, newspaper columns, her first book, and freelance writing that continued until she landed a job where her responsibilities matched her abilities, about a decade later.14

Robert H. Hemphill, Jacobs’s first employer and landlord, was an early influence on Jacobs’s writing career, encouraging her lifelong interests in economics, public policy, and systems of thought. An advocate for national monetary reform and a straight-talking financial writer for William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal-American, Hemphill was a proponent of the establishment of a central bank and removal of the dollar from the gold standard (a move that the Roosevelt administration rejected). He was also the chairman of a committee drafting related legislation to be brought before Congress, for which Hemphill hired Jacobs to assist him. She did library research work for him by cutting clippings of useful material and obtaining copies of bills bearing on economics as they were introduced in Congress. Moreover, Jane and Betty rented rooms in Hemphill’s Greenwich Village apartment at 55 Morton Street, which was located just six blocks from the building on Hudson Street that Jacobs would later make her home. To dispel the appearance of impropriety, Jane and Betty described Hemphill as their uncle. Although this was untrue, it is clear that exposure to “Uncle” Hemphill’s legislative work inspired Jacobs to compile the “rejected suggestions” of the Constitutional Convention of 1787 in her first book, Constitutional Chaff, in which she acknowledged his enthusiasm and wisdom.15 But with only part-time work for Hemphill, Jacobs continued hunting for more work and exploring the city. As she looked for work in the business and industrial districts between Wall Street and Midtown, she wrote about them.

Jacobs found a few weeks of employment working for a stockbroker named George Rushmore, who was writing a book on the stock market, and other temporary work at a drapery manufacturer, the Westclox clock-making company, and Dennison, an office supplies manufacturer. Between November 1936 and May 1937, she worked as the assistant to the vice president of the Scharf Brothers candy manufacturer located at 10th and 51st streets in Hell’s Kitchen, and, from June 1937 to September 1938, as a secretary for the Peter A. Frasse and Company, a maker of bicycle, automobile, and aircraft components, in the industrial Lower West Side. At Peter Frasse, where she worked until starting college in 1938, Jacobs’s responsibilities evolved from stenographer, to correspondence writer, to what she described as the newly created position of “trouble shooting secretary,” where her role was to “step into any department which seemed to be bogging down and help devise ways for getting the work out faster.”16

Jacobs’s work at Peter Frasse, as with her first job at the Scranton Republican, followed a pattern of advancement that would be typical of her career. She quickly gained new responsibilities and independently took on new ones. When these were not demanding or interesting enough to satisfy her, she pursued independent writing projects. With the city and the search for work during the Depression preoccupying her, it was the working districts of the city themselves that she quickly gravitated to, and these became the subjects of her first essays on the city. It was the beginning of a lifelong interest in the geography—historical, physical, social, and economic—of cities.

The Radiant City’s Working Districts

When Le Corbusier visited New York in 1935 to promote his ideas and an exhibition of his work, the architect-planner described the neighborhoods between the skyscapers of Wall Street and Midtown where Jacobs worked as the “urban no-man’s land made up of miserable low buildings.” In Le Corbusier’s eyes, these low, congested, “ground-killing” neighborhoods were insalubrious and inefficient, while skyscrapers like Rockefeller Center offered evidence that all could see of the power of modern architecture, rational planning, and the city of the future. Jacobs marveled at the skyscrapers too. As captured in the iconic photographs of Lewis Hine, their construction bespoke the aspirations of the city, the nation, and humanity. As for Rockefeller Center, which was under construction during her first years in New York—and where, although she could hardly have dreamed it as a teen, Jacobs worked as a writer for Time, Incorporated in the 1950s— she came to see the complex as proof that a large and unified group of buildings could be strategically inserted into the city’s existing urban fabric without the destruction typical of urban renewal projects. However, Jacobs’s and Le Corbusier’s visions of the city, which would clash so dramatically in Death and Life, were diametrically opposed. Soon after moving to New York, she quickly recognized that the city’s unpretentious working districts and their old buildings were as significant as its “financial districts” and its skyscrapers, or more so in the wake of the financial collapse. These districts were the radiant energy of the city’s “metaphoric space-defining fires.”17

Although Jacobs had been to New York as a child, both she and Le Corbusier explored and encountered the city anew in 1935, and both recounted their impressions in November of that year. As reported in the New York Times, on November 3, the city excited Le Corbusier greatly; it was a “wilderness of experiment toward a new order,” whose contrasts elated and depressed him from moment to moment. From the deck of the ocean liner Normandie, the city appeared as a dream city, a vision of enchantment; up close, Le Corbusier was appalled by “the brutality of the great masses—the ‘sauvagerie’—the wild barbarity of the stupendous, disorderly accumulation of towers, tramping the living city under their heavy feet.” The precious ground was wasted, as was time better spent in work or leisure than trying to cross it by foot and car. Looking at the Empire State Building, the tallest in the world, from the top of the RCA Tower, he declared the skyscrapers too small, although, in experiencing them for the first time, he could now imagine skyscrapers not just as office buildings but as residences. Cast as “the exact opposite” of his revolutionary 1922 “Contemporary City” plan, New York exceeded his low expectations; it was his first real experience with the modern metropolis. He loved the democracy, the internationalism, and the “event” of New York, Grand Central Terminal, the George Washington Bridge, Louis Armstrong and the city’s music; the social and economic inequality, the racism, and the slums he found insufferable. From photographs, he presumed the visual cacophony of the city’s hodge-podge of buildings to be a social and aesthetic affront; seeing it in person, he admitted that its energy produced moments of sublime greatness. But caught in a series of traffic jams in the “no-man’s land” trying to get from uptown to downtown, he was all the more convinced in his ideas. Experience, the historian Mardges Bacon wrote, “rarely changed his preconceptions; reality rarely changed his myths.” It was the opposite with Jacobs.18

Two weeks after the Times reported Le Corbusier’s impressions of New York, Jacobs published the first of a series of four essays on the city in Vogue. Anticipating ideas later expanded on in Death and Life, the essays bookend the decades between the start of Jacobs’s writing career and her first book on cities, while contrasting what was important to her with new ideas about the modern city.

In many ways, Jacobs was as much a functionalist as Le Corbusier and other modern architects—possibly more so, because she was not overly concerned with aesthetics. Indeed, while Jacobs first described her idea for the book that became Death and Life as a study of the relation of function to design in larger cities, it was in New York’s working districts that she first came to understand how “diverse city uses and users give each other close-grained and lively support,” as she later described the phenomenon. And as Le Corbusier charged architects to see again, Jacobs would do the same. She wrote in Death and Life, “To see complex systems of functional order as order, and not as chaos, takes understanding,” and she learned this early in her New York experience. Looking down from the roof of her apartment in Greenwich Village, she watched the garbage trucks on their rounds and thought “what a complicated, great place this is, and all these pieces of it that make it work.” Even garbage collection, no small task in the great city, made her think about how the city functioned at its most basic levels.19

In writing about the no-man’s land between the skyscrapers of Wall Street and Rockefeller Center, Jacobs sought to reveal to her readers how the everyday, pedestrian city worked and evolved. Although the premise went unstated, her essays on Manhattan’s Fur, Leather, Diamond, and Flower districts—published between late 1935 and early 1937, when Jacobs was nineteen and twenty—were written to offer Vogue’s uptown readers some insight into the material histories of their prized possessions, the invisible processes and networks that preceded their consumption. In the first, “Where the Fur Flies,” published in November 1935, Jacobs described how furs followed a rough-and-tumble journey from trapper to fur farmer, auctioneer to dresser, dealer to manufacturer to retailer. In “Leather Shocking Tales,” published in March 1936, she explained that cowhide used for shoes went through a process that left nothing to waste: It first had the soles stamped and cut from it; from the remaining network of scraps, heels were cut; then shoe tips, and finally washers for plumbing and buttons were produced. What is left went off to fertilizer factories. “Diamonds in the Tough,” published in October 1936, revealed that most of the sparkling jewelry sold in the “tough” and squalid Diamond District was not new but sold by pawnbrokers after the thirteen months stipulated by law had elapsed from the time it was pawned. Lastly, in “Flowers Come to Town,” published in February 1937, Jacobs told the story of how flowers traveled by truck, boat, and plane to get to New York. Most, she explained, came by truck from Long Island, Connecticut, and New Jersey, but those from Florida, California, and Canada came by express train, and those from South America and Holland by ship. Occasionally, a shipment of gardenias was flown in from California by airplane, while other flowers left the city again by ocean liners and airships: “All the large passenger liners are supplied from the New York market, and, on her eastward trips, the Hindenburg, too, carries flowers from Twenty-Eighth Street.”20

Attentive to the networks of productivity and geography, Jacobs revealed the bouquet on the Vogue reader’s windowsill as more than a pretty arrangement: It was emblematic of the city’s station in international commerce. Though not native to the city, all of these goods—furs, leathers, diamonds, and flowers—were city products, products of the city’s networks of process and exchange. Having recently experienced living in a subsistence economy, Jacobs understood the significance of the city economies, the tremendous physical and social infrastructure that brought raw materials to market. Indeed, she already had some latent understanding about the relationship of city and rural economies. As she wrote years later in The Economy of Cities, “When we see a factory out in the country, we do not automatically assume that the kind of work being done in the factory originated and developed in the country.” Such observations were, intellectually speaking, not far out of reach of the young Jacobs; her interests in economic geography, explored in courses at Columbia University not long after writing these essays, were already well established within her first few years in New York.21

Jacobs was not interested only in the productivity of the city’s working districts: Her vignettes of the city also described the complex interactions between people, places, and practices that defined the diverse and lively human ecology of New York and other great cities. The significance of history and context, temporal and spatial juxtaposition, and cultural and economic diversity were clear to the young writer. In her essays, Jacobs showed places that most New Yorkers did not understand, due to changes in space and time, and did not visit because they were located in the working-class districts of the Lower East and West Sides, where the uptown Fifth Avenue shoppers did not tread.

Although the Leather District, for example, was under the escarpment of the Brooklyn Bridge, it had once been located outside of the city, a perfect case study of a rural satellite of city commerce. “When Wall Street really had a wall and was the northern boundary of the city,” Jacobs explained, “the Dutch citizens of New York asked the tanners and leather merchants to carry on their business beyond smelling distance. They obligingly moved out to a swamp in the wilderness just south of where the Brooklyn Bridge is now, and there they have remained for more than two hundred years, letting the city grow up about them.”22

By contrast, it was unclear to her why the Diamond District, “a glittering island in the most squalid section of New York City” located between Hester and Canal streets in the heart of the Lower East Side ghetto, grew up where it did. “No one seems to know why this location was chosen or why the district continues here,” she wrote. “Twenty-five years ago, the first of the merchants settled in this incongruous setting for no reason now remembered. It is adjacent to no allied centers; it exists by itself, across the street from the entrance to the Manhattan Bridge, surrounded by the almost legendary Bowery life.”23

What was already clear to Jacobs was that these districts did not develop in a vacuum isolated from history or social, economic, architectural, and geographical context. She took it for granted that the great city was a global metropolis, populated by people from all over the world. And unlike many other observers of the city at the time, there was no hint of condescension in her discussion of the ethnic, working-class districts, which others saw as the home of the unwashed masses. In “Flowers Come to Town,” the most poetic of the four essays, Jacobs drew a parallel between her description of the many varieties of flowers on display and the cultural diversity of immigrant shopkeepers, which implied that the great city’s diversity paralleled that of the natural world. Although originally centered around the ferry landing at 34th Street and the East River, a new Flower District grew up around 28th Street and 6th Avenue in the Middle West Side as Greek, Italian, and Asian immigrants set up shop behind the neighborhood’s nondescript brownstone fronts. Anticipating the chapter “The Need for Aged Buildings” in Death and Life, the young Jacobs seems to have already understood the importance of old buildings to city economies as business and culture incubators. As in a natural ecosystem, the city, and its old buildings, sheltered them in ways that modern skyscrapers, no matter how efficient and modern, could not.

Jacobs’s nascent understanding of context, interconnectivity and self-organization, history, and city dynamics was in notable contrast to the revolutionary, antihistorical, and utopian spirit of modernism that was taking hold around her. A child of the Machine Age and the suffrage movement, Jacobs was perhaps too young to experience modernity as a rupture with tradition and the dawn of a new epoch, “one of the great metamorphoses of history,” as Le Corbusier’s generation saw it. Her impressionable moment was the experience of New York City of the Great Depression, which she celebrated for its ability to continue to work. Despite the Depression, and the city’s congestion—or rather because of it—the city continued to tick like clockwork, as in the Fur District, where, from morning until the end of the day, “a steady flow of fur-heaped handcarts and racks runs north, and a stream of both empty and full ones runs south.” However, if others saw the need to re-plan and re-create the city in the image of the machine, it was, for her, more than a machine.24

As Jacobs later explained with her bonfires metaphor, the city defied being reduced to a single and simple “design device” that could express its structures and functions. Her early essays anticipated her rejection of the promise that new architecture and a new city plan could ameliorate the city’s disharmonies and inequities. Just the opposite: Jacobs found the spirit of New York and its hope for the future in these working neighborhoods, where diverse city functions and people lent each other “close-grained and lively support.” Le Corbusier hated the congested inefficiencies of New York’s streets—“the streets of the new city have nothing in common with those appalling nightmares, the downtown streets of New York,” he wrote in 1929—but Jacobs found the essence of the city in its vibrant street life. Le Corbusier saw his imagined Radiant City as the promise and expression of a productive and ennobled society, but Jacobs looked for this in the existing city, in how people and the city worked together and created one another.25

Slumming and Unslumming

As Paris transformed Charles-Édouard Jeanneret into Le Corbusier, New York transformed Jane Butzner into Jane Jacobs. Greenwich Village— the working district whose primary products were the written word, the arts, and other forms of cultural experimentation—was described in 1935 as “the center of the American Renaissance or of artiness, of political progress or of long-haired radical men and short-haired radical women.” The Village was clearly the right place for a twenty-year-old amateur poet and aspiring writer, who soon experimented with the bohemian eccentricities of dress and behavior. If it was possible to reinvent oneself anywhere, Greenwich Village could hardly have offered the young Jacobs greater possibility or inspiration.26

Like the larger city, the Village was also changing as people like Jacobs gravitated to it. In fact, Jacobs was a latecomer to the Village’s latest wave of gentrification and revitalization, which the young author of the Vogue series would have understood from both history and personal experience. As Caroline Ware wrote in Greenwich Village, 1920–1930—published in the same year Jane and her sister moved to Hemphill’s apartment on Morton Street—African Americans and immigrants had “retreated before the advance of the Villager,” and high rents forced out many artists by the late 1920s. A national newspaper headline of 1927 stated “Greenwich Village Too Costly Now for Artists to Live There: Values Increase So That Only Those Who Can Write Fluently in Check Books Can Afford It.” As Jacobs later described it in Death and Life, Greenwich Village was an “unslummed former slum.” It was an exemplary, and personal, case study of the forces of city life, death, and rebirth—of “unslumming.”27

Greenwich Village’s first wave of gentrification had occurred a hundred years before Jacobs moved there, when, in the 1820s and 1830s, epidemics in the walled city of New York drove those who could afford it to the outskirts of the city, where they displaced freed African slaves and created a pastoral suburb. Anticipating future events, an early city-financed urban redevelopment project, which turned a paupers’ cemetery into the Washington Square parade ground, contributed significantly to the area’s development. In 1836, New York University erected its first buildings on the east side of the square, and the “American Ward,” as Greenwich Village became known, soon became the home of libraries, literary saloons, and art clubs, attracting its first “creative class.”28

As New York grew northward, pushed by waves of immigration into its suburbs, the Village slowly transformed into a crowded and ethnically diverse industrial slum. Warehouses were converted to factories and its deteriorated housing stock was subdivided into hotels and tenements. As Jacobs later wrote in Death and Life, colored people and immigrants from Europe eventually surrounded the American Ward, and “neither physically nor socially was the neighborhood equipped to handle their presence—no more, apparently, than a semisuburb is so equipped today.” The white middle-class community fled to settle the Upper East Side and a new suburb in Harlem—“a new quiet residential area of unbelievable dullness”— and left Greenwich Village to deteriorate, only to be revived again by a new wave of writers, playwrights, painters, and those that followed them in the decades before Jacobs arrived.29

Jacobs came to see herself as part of these city dynamics, the product of many individual decisions—like her decisions to move from Scranton to New York and then to the Village. As she wrote in a subtle biographical allusion in Death and Life, Greenwich Village was an “unslummed former slum” because it had attracted an energetic, ambitious, and affluent population. Whereas “dull neighborhoods are inevitably deserted by their more energetic, ambitious, or affluent citizens, and also by their young people who can get away,” high-vitality neighborhoods attracted “vigorous new blood”—like hers.30

In Death and Life, Jacobs used the term “slum” for shock value, challenging notions of what a slum was (or is) and the people who live in them, as well as the inadequacy and imprecision of the term in city planning theory. She explained that the “unslumming” process required longtime residents, in addition to the admixture of “new blood,” to participate in a neighborhood’s renovation. The process hinged “on whether a considerable number of the residents and businessmen of a slum find it both desirable and practical to make and carry out their own plans right there.” Contrasting with paternalistic, top-down decisions of legislators and city planning theorists to move and transform neighborhoods and their residents, “unslumming” represented self-determination, participation, and the latent power of what was “possibly the greatest regenerative forces inherent in energetic American metropolitan economies.”31

Although Jacobs did not delve too deeply into city history in Death and Life, she knew that parts of the city had improved dramatically, despite exponential population growth, in the years before she moved to Greenwich Village and Le Corbusier visited Manhattan to promote his Radiant City. By 1930, the Lower East Side’s population had been halved from its high of 530,000 to 250,000, as residents moved to the boroughs of Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx. She also knew this was not true for other parts of the city or for other cities. “Colored citizens,” she wrote, “are cruelly overcrowded in their shelter and cruelly overcharged for it. The buildings are going begging because they are being rented or sold only to whites—and whites, who have so much more choice, do not care to live here.”32

Considered the worst slum district in the world by the early 1800s, Manhattan’s Lower East Side had already been the focus for the best intentions of housing and social reformers for over a century. Disadvantaged by its swampy geography at a time when Greenwich Village was a bucolic location for colonial agricultural estates, the area, as Jacobs observed in her early essays on the Diamond and Leather districts, was the home of the people and enterprises—freed slaves, Jews, tanneries, slaughterhouses, and breweries—that were expelled from the old walled city. Eventually it became the city’s working district for vice, not to mention gangs and impoverished tenement life. In the first in a long series of New York slum-clearance “firsts,” after being granted use of the powers of eminent domain by the state legislature in 1800, in the 1830s the city government razed part of the Five Points core and created a park. Anticipating the redevelopment strategies, the enduring overestimation of the virtues of parks, and the gang battles of 1950s New York, all described by Jacobs in Death and Life, the paradoxically named Paradise Park soon became a site for gang warfare. Also anticipating the “white flight” of the mid-twentieth century, the mid-nineteenth century saw the design of the first planned suburbs in the United States, among them the aptly named Irving Park (1843), outside of Chicago, and Llewellyn Park (1853), outside of New York. As Henry James wrote during that time, “New York was both squalid and gilded, to be fled rather than enjoyed.”33

By the 1880s, the late nineteenth-century pastime known as “slumming”—“the latest fashionable idiosyncrasy in London, i.e., the visiting of the slums of the great city by parties of ladies and gentlemen for sightseeing”—had reached New York. An 1884 New York Times article discussed the “best” districts for sightseeing, noting that there were many good places for the curious sightseer “to see people of whom they had heard, but of whom they were as ignorant as if they were inhabitants of a strange country.” But the flip side of slum literature and tourism was reformism. In London, “slumming has brought to the notice of the rich much suffering, and led to many sanitary reforms,” the author observed, although this was not yet the case in New York: “So far the mania here has assumed the single form of sight-seeing—the more noble ambition of alleviating the condition of the desperately poor visited has not animated the adventurous parties.”34

However, the urban reform movement, the foundation for urban renewal concepts and programs that Jacobs would later seek to reform in turn, grew quickly. Paralleling the British experience, the popularity of salacious publications about slum life, such as Darkness and Daylight, or Lights and Shadows of New York Life (1892), was followed, and capitalized on, by reform literature such as police-reporter-turned-photojournalist Jacob Riis’s exposé How the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York (1890). Prompted by Riis and growing public attention, the city government razed the “foul core” of the Lower East Side for a second time in 1888 and, with the assistance of the Small Parks Act of 1887, turned the razed site, once again, into a park, repeating a pattern of redevelopment practices that would continue into the urban renewal era of the 1950s and 1960s. In an 1891 Times article titled “A Plea for More Parks,” Riis and reformers from the Union for Concerted Moral Effort, a group of uptown religious leaders, declared their mission “to make war on the slums and cut them to pieces with parks and playgrounds.”35

Located in the heart of the neighborhood that Jacobs later visited for her “Diamonds in the Tough” essay, Mulberry Bend was a few blocks from the Five Points slum clearance of 1833, but more ambitious; it is considered one of the first slum clearance projects on a modern scale. Not without the difficulties of such an effort, almost ten years passed before Mulberry Bend Park (later Columbus Park) opened in 1897. Anticipating future debates about public-private development that would continue into the present, the park’s construction was delayed by the familiar dilemmas of determining compensation for the owners of the condemned properties, evicting tenants, and wrangling over whether adjacent property owners—who would ostensibly profit from proximity to a new pleasure ground—should bear part of the cost of the public investment. It was a project exemplary of the “creative destruction” of Manhattan, with all the contradictions that the historian Max Page implied with that term. Also representing the thinking about parks and sentimentalized nature that Jacobs criticized in Death and Life, a reporter wrote that a proper and picturesque people’s pleasure ground would be “a welcome bit of green nature that will be more than grateful to a wretched and hopelessly poverty-stricken part of the community, comprising people of various nationalities, with scarcely an American among them.”36

Despite the hoped-for benefits of this green design, transportation, not public space, ultimately transformed the Lower East Side. In addition to advocating for municipal parks for the poor, in 1891 leaders of the Union for Concerted Moral Effort also lobbied for a municipally owned transit system that would solve the problem of city crowding by making less congested districts, such as Harlem, accessible to the working class. By 1890, Manhattan’s elevated railroad system was the longest in the world, but it was slow, overcrowded, expensive, privately owned, and had limited connections to neighboring cities off the island. Although far less radical than contemporary proposals to reform land ownership, the idea of a municipally owned transit system was considered by some to be “socialist,” but it eventually came to pass.37

By the time Jacobs settled in Greenwich Village, one of the worst slums in the world had uncrowded and unslummed, even as the city’s population continued to grow, as half of the Lower East Side’s population took advantage of the recently expanded subway system and moved to the outer boroughs of Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx. Greater New York’s first subway opened in 1904, and the privately owned Interborough Rapid Transit line soon carried six hundred thousand people daily. In the 1920s, with the support of Governor Alfred E. Smith, a native of the Lower East Side, the privately owned Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit system added seven new crossings of the East River. Finally, in 1932, a few years before Jacobs moved to the city, the municipally owned Independent Rapid Transit Railroad added 190 miles of subway. The melodramatic roar of the Els, which were torn down as the subways were built, soon became a lost part of changing New York.38

Thus, Jacobs moved to New York at a remarkable moment. On the one hand, the New Deal provided the means for a host of reform-minded projects and infrastructural improvements. Public works funding allowed Mayor Fiorello La Guardia and Robert Moses, his new parks commissioner—who was by then the chairman of the Emergency Public Works Commission, a former New York secretary of state, the former chairman of the Committee on Public Improvements, and a mayoral nominee in the race won by La Guardia—to implement their pre-Depression lists of proposed building projects, including parks and parkways, bridges and swimming pools, hydroelectric dams and airports, and public housing. The year Jacobs moved to New York also saw the birth of the planning organization that she would battle twenty-five years later. In 1934, assisted by the Works Progress Administration (WPA), La Guardia formed the Committee on City Planning, which led to the establishment of the New York City Planning Commission in 1936. Meanwhile, also in 1934, the new NYC Housing Authority assumed control of housing construction work initiated by the WPA, and it quickly conceived of the largest slum clearance housing project ever undertaken, the predecessor of the types of projects that Jacobs railed against in Death and Life.

On the other hand, Jacobs arrived in New York when, because of the automobile, city life was becoming a choice for the upper and middle classes. Following the transit-oriented Sunnyside Gardens housing project (1924), which was located adjacent to an elevated station in Long Island City, the architect Clarence Stein and the planner Henry Wright’s Radburn, New Jersey, project (1928) was designed to be the “Suburban Garden City for the Motor Age.” Working with Frederick Ackerman, the chief architect of the new Housing Authority, Radburn’s “superblock” plan was meant to eliminate “the annoyances of old-time towns” and cities by incorporating the automobile into daily life. In the 1929 Regional Plan of New York and Its Environs, Radburn was held out as “a significant contribution to the plan of the Region” as a whole, meriting “every possible financial support and encouragement from public authorities.” Although Modernist architects were later blamed for conceiving the superblock plan and automobile-oriented design, the car and the problems it created were entrenched when Jacobs was still a teenager. Although equally captivated by the suburb’s verdancy, even Le Corbusier recognized the problems. In 1935, he prophetically stated, “The suburb is the great problem of the U.S.A.” While also mesmerized by the automobile (and who wasn’t?), unlike aggressive decentrists, Le Corbusier’s ideas were based on preserving the countryside from the “vast, sprawling built-up area encircling the city,” eliminating long commutes “spent daily in the metros, buses, and Pullmans that cause the destruction of the communal life that is the very marrow of a nation,” and keeping people and their homes “in the middle of the city instead of in Connecticut.” Nevertheless, those who advocated decentralization recognized similar problems with the self-segregation and planned segregation of the suburbs. As Lewis Mumford wrote in The Culture of Cities (1938), “Without doubt the prime obstacle to urban decentralization is that a unit that consists of workers, without the middle class and rich groups that exist in a big city, is unable to support even the elementary civic equipment.”39

Such were the forces and the “historic changes,” as Jacobs called them in Death and Life, that would shape the fate, and the life and death, of cities. If they could afford it, those seeking more space and greenery moved to the suburbs, just as others had left the walled city of Manhattan for the suburbs of Greenwich Village centuries before. Jacobs naturally believed in the choice of where to live, but unslumming, she wrote in Death and Life, hinged “on whether a considerable number of the residents and businessmen of a slum find it both desirable and practical to make and carry out their own plans right there.” Cities may have held an attraction for some, but, as Ebenezer Howard observed in Garden Cities of To-Morrow (1902), the country was a magnet for others.40

First Houses

When Eleanor Roosevelt dedicated First Houses, the first municipally built, owned, and managed housing project in the United States, a crowd of ten thousand attended, despite the cold weather. Le Corbusier, who had been touring the city’s slums and housing projects with the Housing Authority’s chairman Langdon Post and House and Garden editor Henry Humphrey, was there, as was Moses. It is tempting to think that Jacobs, who lived a short distance away, was there to observe the spectacle and to witness the rise and fall of New York City public housing from start to finish.41

The First Houses dedication was an event of national significance. A telegram from President Roosevelt read by Post at the dedication called the project an “answer to the great national need for better American homes and housing conditions.” Mrs. Roosevelt added, “I hope the day is dawning when private capital will devote itself to better and cheaper housing, but we know that the government will have to continue to build for the low-income groups. That is a departure for us, but other governments have done it.” Governor Herbert H. Lehman similarly described the project as the start of “a new field of public responsibility.” Observing that the United States was twenty years behind European countries in eliminating slums and providing affordable housing for its citizens, he added that the Depression had made the shortage of housing an emergency situation:

The clearance of slums and the provision of new dwellings for low-income families in our state has opened up a new field of public responsibility. Previous to the still existing depression, it was assumed by the majority of people that the housing problem was a personal one, a matter of individual responsibility. [But] students of housing have been well acquainted with the great programs of rehousing which cities of Great Britain and continental Europe have been developing in many years past. Over twenty years ago in cities abroad, local communities undertook to serve the housing needs of those families who found it impossible to provide for themselves homes of modern standards at rents within their means. Under the pressure of emergency people have acquired a new sensitiveness to human values and human needs. We are no longer indifferent to conditions which in the past we have taken for granted.42

Located at East 3rd Street and Avenue A on the East Side (an area later known as the East Village), First Houses has been described as one of the best public housing projects ever built, in part for its subtle and contextual design. Nevertheless, at the time, it was generally considered a failed experiment. Mayor La Guardia, a Greenwich Village native, was proud of the housing program, and he boasted of the diversity of backgrounds represented on the housing board, which included Post, the Greenwich Settlement House director Mary K. Simkhovitch, the Catholic Charities administrator Rev. Roberts Moore, and the American Labor Party leader Charney Vladek. He exclaimed, “Where can you find a housing board to equal it—an idealist on housing, a social worker, a Catholic priest, and a Socialist!” However, as a housing prototype, he called First Houses “Boondoggling Exhibit A.”43

FIGURE 6. First Houses, Lower East Side, dedicated by First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt on December 3, 1935. NYCHA and LGWA.

Designed by Frederick Ackerman and William Lescaze, First Houses’ great shortcoming was providing too few apartments at too great a cost. Initially meant to be a renovation of the existing tenements, where every third tenement building on the site would be demolished in order to provide daylight and fresh air, along the way it was discovered that the 1846 tenements were in too poor a state to be rehabilitated. After three of the eight were renovated, all but a few walls and the foundations of the rest were torn down, and new apartments were built from the salvaged bricks. Reuse of the old bricks allowed the new buildings to blend in with the old, but at the time this underscored the project’s lack of modernity, while proving renovation to be a very costly approach.44

Criticized as “a million dollar extravagance” because of its cost overruns, the first public housing project thus helped to kill the idea of renovation as a slum improvement tactic decades before Jacobs’s criticism of postwar urban renewal. In 1936, the housing consultant and attorney Charles Abrams (later cited in Death and Life) was among those who argued that “it will be far cheaper to demolish the old buildings and reconstruct the areas anew.” Similarly, Jacobs’s future friend and foe Lewis Mumford— who believed that even the city’s wealthiest citizens lived in antiquated and inadequate quarters—wrote of First Houses in his column for The New Yorker, “The external environment remains exactly what it was before: bleak, filthy, ugly…. These new tenements would be expensive at half the price. This is ‘slum replacement’ with a vengeance—it simply replaces an old slum with a new slum. Congratulations, Mr. Post!” Despite becoming known as the great destroyer of city neighborhoods, Moses was among those who defended the idea of renovation. Still bitter a decade later over Abrams’s criticism of his advocacy for rehabilitation, Moses wrote, in 1945, “The perfectionist does not want old buildings made sanitary and fireproof. … He says this move perpetuates the slum and gives it a new lease of life when it is about to die a natural death. He favors rehabilitation only if every third house is torn down and the two remaining ones completely rebuilt; and he can show that this process is so expensive that it is hardly worthwhile. Yet it is a fact that in most cities plenty of old tenements and other houses can be made safe, sanitary, and fairly comfortable for a number of years at a reasonable cost.”45

With overwhelming criticism, Post could only concede that First Houses had cost too much and direct his agency to provide more apartments for less money. He answered his critics by stating that the first public housing project had been a useful experiment that was only the beginning of a “vast housing plan” that would rehouse five hundred thousand families throughout the city over the next ten years. First Houses’ enduring contribution had been “to test the Authority’s power to condemn land for slum clearance—a test which we won,” he added. By upholding the Housing Authority’s power to condemn two parcels that an intractable owner had refused to sell, a State Appeals Court established a significant legal precedent for the use of eminent domain upon which future urban redevelopment was predicated.46

Post’s Housing Authority now had something to prove and the legal means to prove it. However, this would not be easy in a severely depressed economic climate. In the Roaring 1920s, housing projects had been far more ambitious. Whereas First Houses had 123 apartments, midtown Manhattan’s Tudor City, built only ten years earlier by the speculative real estate developer Fred French on the site of East River slums, had three thousand apartments and six hundred hotel rooms in twelve elevator buildings surrounding a private interior park. The product of a pre-Depression, developer-driven, and pre-Modernist urbanism of hyper-density, Tudor City represented an architectural approach aptly described as “Manhattanism.” But while Tudor City was a ritzy precedent, in the early 1930s Manhattanism was an unattainable development dream in public housing circles. Less than five years before First Houses opened, drawings had been made for a “city of the future” to replace the slums of the Lower East Side’s Chrystie-Forsyth neighborhood, razed in 1930. In its place was imagined a skyscraper city flanked by a new multilane automobile parkway and viaduct expressway designed to improve circulation to the Manhattan Bridge. With spotlights illuminating the sky and a multilevel transportation system, the proposal was a visionary combination of Beaux-Arts civic design, nineteenth-century technophilia, and Jazz Age futurism.47

Among the last pre-Depression expressions of Manhattanism, and one that made First Houses pale in comparison, was a public-private partnership for a high-rise, high-density development of 1,600 apartments called Knickerbocker Village, located just five blocks from Mulberry Bend and completed in 1934 around the time of Jacobs’s visit to the Lower East Side for her first working-district essay. The project—also designed by Frederick Ackerman and developed by Fred French, who had acquired the land by the summer of 1929—would not have been completed due to the stock market crash except for the support of Moses, the chairman of the city’s Emergency Public Works Commission. As the New York Times observed in 1933, “Any undertaking with which Alfred E. Smith and his ‘fidus Achates’ [faithful Achates] Robert Moses, are associated has a way of moving swiftly and with decision.”48

Although the site was a notorious, tuberculosis-ridden “lung block,” which had been identified as a slum clearance site as early as 1903, French’s original plan was to transform Knickerbocker Village into a “high-class” residential development from which Wall Street executives could walk to work. However, with an $8 million loan from President Hoover’s Emergency Relief and Construction Act of 1932, secured with Moses’s intervention, the project became the federal government’s first major involvement in housing development, and Knickerbocker Village was ultimately rented to middle-class families, among them some fallen Wall Street tycoons. In the new economic context, it was also clear that such projects would do little good for the slum dwellers of the Lower East Side, and using public funds to displace low-income tenants, gentrify neighborhoods, and profit real estate developers gave some pause. Indeed, the housing problems that Jacobs later wrote of had a long history. In an April 1933 expose in The Nation, the local Socialist Party organizer Henry Rosner wrote that, despite all the publicity surrounding the demolition of the notorious “lung block,” the neighborhood’s original residents would only be worse off for being displaced. Anticipating Jacobs’s critiques in Death and Life, he wrote that “the displaced tenants will merely move into old-law tenements on the next block which will be a little less dreary, dilapidated, and unhealthy. … Two blocks of slums will be destroyed, but several others will be perpetuated.”49

Progressive critics, including Ackerman and Moses, agreed. Commenting on Rosner’s article, Moses replied that the solution to large-scale slum clearance and low-cost housing would be federal subsidies—exactly what would soon come to pass in New Deal and later in Urban Renewal housing legislation. Keenly anticipating the future, in a private letter Moses wrote, “I know the limitations of the Knickerbocker Village and I think I have some idea of what ought to be done on a large scale. It was immensely difficult to get this one project under way in the face of the reluctance of city officials to grant tax exemption and the bitter opposition of real estate and other interests. … [T]he solution of the problem lies at Washington, and if proper provision can be made by law for slum clearance and low-cost housing as part of a reorganized Federal Public Works program, we can get somewhere. This probably involves a Federal subsidy.” In this way, Knickerbocker Village was the end of Manhattanism and also the beginning of slum clearance and housing development with federal legislation and funds, a turn of events that Moses understood as early as 1933, the year Jane Butzner, his future nemesis, graduated from high school.50

From “Manhattanism” to the “Radiant Garden City”

While the Great Depression mortally wounded Manhattanism, suburbanism dealt it a deathblow. Whether sympathetic with Howard’s exurban “Garden City” or Le Corbusier’s urban “Ville Verte,” suburban-minded reformers agreed that the Knickerbocker Village housing model was too much like the slums they replaced: It was too dense and covered too much of the ground to provide the desired amounts of light, air, and open space. Indeed, irrespective of architectural style, the longing for and sentimentalization of nature had been the undoing of cities, and the driver of sprawl, since long before Jacobs criticized suburbanism in the conclusion to Death and Life. Even as Le Corbusier and the other European architects referred to by Eleanor Roosevelt at the First Houses dedication were at work, New York architects were developing an indigenous “garden apartment” type that evolved into a new model of “suburbanized urbanism.”51

First built in the suburbs of Queens in the 1910s, the suburban model was introduced into the city by the 1920s. In those years, the architect Arthur C. Holden, a future acquaintance of Jacobs, invented a prototypical urban redevelopment model that was a cross between high-density Manhattanism and the low-density New York garden apartment, seeking to combine the advantages of urban density and suburban open space. Contemporary attention to modern European housing only seemed to prove the local model right. In 1932, the Museum of Modern Art’s Modern Architecture exhibition of 1932 included a companion exhibition on housing organized by Clarence Stein, Henry Wright, Lewis Mumford, and Catherine Bauer—also Jacobs’s future collaborators, friends, and antagonists—that made European models hard to ignore. As Douglas Haskell, the architecture critic for The Nation and Jacobs’s future boss, wrote in March 1932, European housing, such as Ernst May’s fifteen-thousand-family housing project in Frankfurt, represented “the best that the twentieth century can do for the average man.”52

A few years before Jacobs moved to New York, these varied forces converged in a number of groundbreaking plans by the Philadelphia and New York–based architectural firm of Howe & Lescaze. One of the most celebrated American architectural practices after its completion of the first modernist skyscraper in the world in 1932, the PSFS Building in Philadelphia, Howe & Lescaze embodied the attempt to synthesize European modernism and American suburbanism. Between 1931 and 1933, even as work on the urbane PSFS Building continued, the firm submitted a proposal for the still vacant seven-block Chrystie-Forsyth site. Their massive, visionary scheme was called River Gardens (aka Rutgerstown) and would redevelop eighteen city blocks on the Lower East Side, from the Chrystie-Forsyth site on the west across to the East River and from Houston Street down to the Manhattan Bridge. Influenced by the architectural principles outlined by Le Corbusier in Towards a New Architecture (1931), the Chrystie project would house 1,500 families in twenty-four elevator buildings with ribbon windows and roof terraces set on fourteen-foot columns; without basements or ground floors and bridging the cross streets, all of the ground space would be free for lawns, recreation, and circulation, allowing children to travel to the public school, planned for the block south of First Street, under cover and with minimal street crossings. Architecturally, the scheme was a forbearer for many public housing projects, including one Jacobs consulted on decades later, in East Harlem, in the late 1950s.53

FIGURE 7. River Gardens, a housing project proposed in 1932 for the Lower East Side by Howe & Lescaze. Lescaze Archive, Syracuse University Special Collections, Syracuse, NY.

River Gardens was originally conceived in 1932 as a $6 million project with nine-story buildings; however, in a revised plan in 1933, the buildings grew to fifteen stories, with a cost of more than $9 million. Ultimately, River Gardens was proposed to house 7,500 families in dozens of midrise buildings of varying height that would occupy only 45 percent of the ground and leave the rest devoted to green space and recreational uses. Designed by Lescaze with the assistance of Carol Aronovici and Albert Fry, who had worked in Le Corbusier’s office from 1928 to 1929 (around the time Le Corbusier wrote The City of To-Morrow and Its Planning), River Gardens evoked Le Corbusier’s “Contemporary City.”54

Both projects were locally supported and approved for construction in 1933, although neither commission went to Howe & Lescaze. Although their “international style”—to use the term coined by Henry-Russell Hitchcock and Philip Johnson in The International Style: Architecture Since 1922 (1932)—was not then embraced by all, style was not the issue. While the Chrystie project was the first in New York that clearly referenced European models—and one of only a few U.S. projects featured in Hitchcock and Johnson’s 1932 exhibition—New York Times articles and editorials celebrated the projects’ basic concepts, which were not unique to Howe & Lescaze’s proposals. Architectural style was a matter of taste, but the underlying city planning principles, so rational and self-evident, were praised. In support of River Gardens, the Times lauded the superblock approach, stating that the building’s limited footprints would create large open spaces for park development and would “secure to city dwellers advantages of sunlight, air circulation, and attractive outlook over garden plots—heretofore not to be had in the congested areas of Manhattan Island.” Named for the 1750 farm owned by Herman Rutgers that once occupied the site, Rutgerstown would “bring back into the city some of the country that was in that favorite area in 1750.” Suburbanism transcended style.55

Chrystie-Forsyth and Rutgerstown failed because of land costs and a dynamic that Jacobs later described as “slum shifting” (or what, a few years after her, the sociologist Ruth Glass termed “gentrification”). In a 1933 Times article titled “East Side Housing Not for the Poor,” John Sloan, the architect ultimately selected for the Chrystie project, explained that the new housing project had to be considered “slum clearance” and not “slum relief.” New apartments could not serve the neighborhood’s poor, Sloan said, because “it is simply impossible to supply decent housing for them at anything like the figures they are now paying for hovels on the most expensive Manhattan real estate.” People who could not pay more than $5 in rent should be transferred to places where land is cheaper, the architect explained, so they can receive decent housing. Sloan suggested that a relocation could occur in Astoria, Queens, near the water’s edge or near the gas tanks (the future site of Stuyvesant Town). Anticipating future developments, he continued, “The development of this section will eventually force the hovels out, and it will become a white-collar residential center for downtown office workers. There is no other way to figure it without a government subsidy to make up the difference between what these people can afford to pay and what it costs for the Chrystie-Forsyth land plus the construction of decent housing on it.”56

Despite the support of the State Housing Board, Mayor John P. O’Brian (who served between Jimmy Walker and Fiorello La Guardia), the Board of Estimate, and East Side community organizations, Rutgerstown was denied the needed $40 million government loan. Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes, the director of the Public Works Administration (PWA), stated that Rutgerstown was “socially desirable from the standpoint that it would clear one of the worst portions of New York slums.” However, there were no more funds available for private housing projects, particularly for expensive Manhattan real estate. As the Times noted in “War on Slums Proceeds Steadily,” “When Langdon Post Jr., Tenement House Commissioner, attempted to buy property on the lower East Side, he found that the price asked per foot was much more than the city could afford to pay. … This also is the case on the lower West Side, in upper Chelsea, where are some of the worst slums in New York.”57

Such was the background for the iconic modernist Williamsburg Houses project (1934–37), the most ambitious slum clearance housing project then undertaken in the United States. Located in Brooklyn, where the slums were “among the worst” and land was cheaper, Williamsburg would be the Housing Authority’s first independently initiated housing project after it took over First Houses from the WPA, and it would bring together the best team that could be assembled. Lescaze, a new member of the Housing Authority’s architectural board, was the lead designer, while Ackerman served as the Housing Authority’s new technical director; Henry Wright, Arthur Holden, and Richmond Shreve and Irwin Clavan, architects of the Empire State Building (Clavan would later design Stuyvesant Town), rounded out the design team.

Hybridizing the New York garden apartment with European modernism, Williamsburg turned twelve city blocks into four superblocks of four-floor apartments. Green and open space accounted for almost 70 percent of the site, exceeding the 65 percent demanded by the PWA, which funded the project. Adding further to the project’s suburban tranquility, storefront buildings were eliminated and shops were limited to only the highest traffic intersections, reducing interior noise and traffic. Meanwhile, light-colored materials, a lack of distinction between the fronts and the backs of the buildings, and the rotation of the echinate buildings fifteen degrees off the city grid reinforced the project’s separation from the neighboring age-darkened and cramped tenement buildings and the rest of the old city.

FIGURE 8. Williamsburg Houses, Brooklyn, designed by Frederick Ackerman and William Lescaze, with possible input from Le Corbusier, 1937. NYCHA and LGWA.

Not all of the architects on Williamsburg’s remarkable design team saw eye to eye. A self-described technocrat, Ackerman was a relatively conservative architect; he had studied in Paris and published an extensive survey of British housing and town planning in 1918, and he objected to the project’s machine aesthetic and the rotated site plan. Ultimately, Lescaze’s hand prevailed, perhaps with the help of Le Corbusier, who visited the Williamsburg site and was a frequent guest at Lescaze’s home and office during his visit to New York. Nevertheless, Williamsburg was the beginning of a new amalgamation of urban design ideals, which, irrespective of the modernistic architectural language, combined broadly shared functionalist and suburbanizing ideas. As presciently described in the Times on October 15, 1936, the day after its dedication, Williamsburg Houses symbolized “the pioneer epoch in American efforts at slum clearance and rehousing” and deserved “a notable place in the history of American housing.” While Williamsburg Houses was not the “towers-in-a-park” scheme envisioned for River Gardens, what Jacobs later called “the Radiant Garden City” had taken root in Brooklyn by the time she was settled in Greenwich Village.58

Creating what Mumford called “the streetless house and the houseless street,” Williamsburg Houses exemplified a “new order,” where the automobile was accommodated, while residences, retail stores, and automobile and pedestrian traffic were all functionally separated. As Mumford wrote in a review of the project, the “first principle of modern neighborhood planning is to reduce the number of streets, convert more open space into gardens and playgrounds, and route traffic around, not through, the neighborhood.”59

In what was probably her first encounter with the Radiant Garden City, Jacobs visited a Brooklyn housing project, probably Williamsburg, around this time, and she wondered about the design and whether people would like it. Despite any critiques she may have had at the time, however, there was an enormous demand for housing. Whereas First Houses had received 15,000 applications for 122 apartments, Williamsburg Houses received more than 25,000 applications for 1,600 apartments; and as Williamsburg Houses was the most expensive public housing project undertaken by the Housing Authority to date, and the most expensive ever built in relative terms, there was ever-increasing pressure to decrease unit costs; to eliminate stores, amenities, architectural fees, landscaping, and materials; and to push the buildings higher—especially on pricier Manhattan land. East River Houses, completed in 1941, around the time Jacobs landed her first writing job, would be the first high-rise housing project. Located in East Harlem, where Jacobs would later come to understand the flaws in this urbanistic system of thought, its superblocks and towers destroyed the city’s preexisting block structure and eliminated the familiar and contextual urban qualities of scale, orientation, public space, and multiple function that, just a few years before, First Houses had retained.60

Within the conceptual paradigm where it was believed that as much as “half the residential area of the city is in an advanced blight or slum,” and where the most expensive residential street in New York City could be described as a “super slum” because its apartment buildings violated the minimum standards of quiet, sunlight, and fresh air, suburbanization, suburbanized urbanism, and the “pathologies” of public housing, soon exemplified by Fort Greene Houses, were inevitable.61

FIGURE 9. Fort Greene Houses, built in 1941 as a barracks for the Brooklyn Navy Yard, had come to symbolize the problems of public housing by 1959. NYCHA and LGWA.

In 1936, Mumford wrote that “what Manhattan needs to overcome its present blight (caused mainly by an exodus to the outskirts and the suburbs) is a series of ‘internal’ suburbs.” And in fact, even as work proceeded on Williamsburg Houses, the suburbanization of the city had begun.62

While at work on Williamsburg, Lescaze, Aronovici, Wright, and Albert Mayer began designing a five-hundred-acre “Garden City within the City” that stretched along most of the East River waterfront of Astoria, Queens, from the Queensboro Bridge to within a few blocks of Moses’s new Triborough Bridge. Described as a new approach, Astoria’s cul-de-sac suburb would have a density of approximately 150 people (and rooms) per acre, with six-story buildings covering 45 percent of a slum-cleared site. Strategically located between two of the bridges off the island, the “new colony” was an ideally located suburb: It was adjacent to Moses’s new Grand Central Parkway (1933–36) and connected by mass transit to many of the city’s fourteen slum areas, as designated by the Slum Clearance Committee of New York, for which all of the team members served as consultants. Recognizing that transportation was inextricably linked to city planning, slum clearance, and housing development, Mayer noted that proximity to the city’s slums with a 5¢ transit fare was “an important factor because the people who move here from the slums will want to visit and be visited by their friends.” And with Moses’s new parkways, automobile ownership was clearly part of the city’s future. In the Times article “New Colony Urged as Slum Solution,” Lescaze argued for embracing this future: “The old pattern of a city must be thrown aside because of the absurd congestion of traffic. A small plan of many streets worked all right in its time, when horses and walking on foot were the only means of transportation. Why not do the intelligent thing and provide a decent pathway for the automobile?”63