BUT AUGUSTA NACK was thinking about Martin a great deal indeed. Even as Harriet prepared her article for the next day’s October 3 edition of the World, Mrs. Nack motioned an inmate over to her cell.

Rockaway! came the summons as he strolled along the top floor of the jail. Rockaway Ed was a trusty, part of the peculiar prisoner hierarchy within Queens County Jail. Ascending to the rank of a trusty meant freedom: freedom to walk the halls and deliver messages and packages, freedom to walk the exercise yard, even the freedom to leave the prison when the sheriff wanted errands run. The trusty was second only to a “bum boss” in the underground ranking of prisoners, and when Journal men had first visited the jail, it was Ed who’d shown them around; he was considered the best guide. When, that is, he could be found there at all. He was on the last two months of a six-month sentence for pilfering some jewelry, and on a good streak he could stay clear of jail for the entire day, returning only to sleep on his hard pallet bed at night.

Ed came up close to the cell door.

“I believe I can trust you,” Mrs. Nack whispered. “And if you will do what I tell you it’s worth twenty-five dollars to you.”

That sounded like escape money, and Ed’s own sentence was going to end before Christmas. “Oh, that’s all right,” he assured her. “I’m not looking for pay.”

“Well.” Mrs. Nack hesitated. “I want to send a message to Thorn, and I want you to take it. I’ll put it in a sandwich.”

Food was a good medium of communication; Mrs. Nack was already known for securing cell-block friendships this way, so food handed through her cell door to a trusty wouldn’t attract any notice.

Three days later when she’d saved up enough food and paper, the parcel passed through the barred door and into Rockaway Ed’s hands. As he walked down the cell block, and then down the three flights of stairs to Murderers Row, he could see that there was more than just a sandwich in the parcel: Whether to hide the note, or simply out of a hostess’s pride, Mrs. Nack had sent a side dish of potatoes as well.

At the bottom of the stairs, it was a straight shot through the iron cell-block door and to Thorn’s room. But Ed bided his time; he knew that sooner or later he’d be wanted by the sheriff for an outside errand, and he was right. Sent out of the jail, he still held Mrs. Nack’s parcel as he walked out through the locked doors, into the autumn sunlight, across the Court Square, and into the outpost of the New York Journal.

Whatever Augusta Nack could pay, William Randolph Hearst could pay better—much better.

I’ve got it, Rockaway Ed announced.

Journal staffers pounced. He’d slipped the lead to them days ago, and they’d been waiting with writers and artists at the ready to make a copy.

Rockaway Ed was hustled back out the door with the letter; he was to go immediately back to the jail and deliver it, they told him. If Thorn wrote a reply, they’d intercept that one, too.

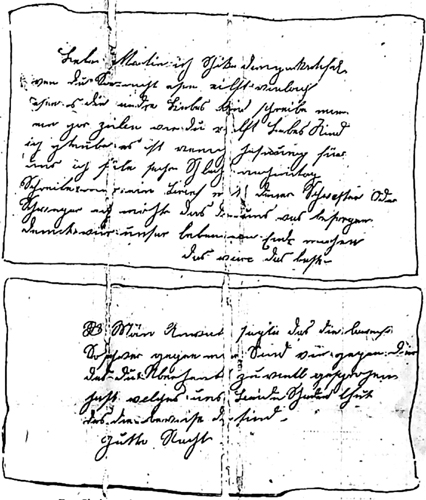

A staffer who knew German quickly translated the note into the text that would appear in the next morning’s paper:

Dear Martin

I send you a couple of potatoes. If you do not care to eat them, perhaps the others will. Dear child, send me a few lines how you feel. Dear child, I believe there is very little hope for us. I feel very bad this afternoon. Send me a letter by your sister or by your brother-in-law. I wish they could procure us something so that we could end our lives.

This would be best.

My attorney assures me the evidence against me is as strong as that against you, and that you have talked too much, which injures us, for the proofs are at hand.

Good night.

It was a puzzling note, because it was palpably false. The evidence was not as strong against her—she hadn’t spoken publicly against Guldensuppe before his disappearance and hadn’t unburdened herself to a friend about killing him. In fact, if it wasn’t for Thorn’s presence, it might have been difficult to mount a murder case against Mrs. Nack at all.

It took a stunned moment to sink in: Mrs. Nack was trying to get her accomplice to kill himself.

“WHERE IS IT?” Sheriff Doht demanded as he burst into Thorn’s gloomy cell. Jailer Jarvis barreled in behind him as Thorn grabbed for his clothing.

“Hand me the vest!” the sheriff yelled. Thorn yanked a sheet of paper out of a pocket and frantically tore it, stuffing pieces into his mouth.

“Don’t let him, that’s what I’m after!” the sheriff barked to the jail keeper. Jarvis closed his beefy hands around Thorn’s neck, choking and rattling him as the writhing prisoner desperately tried to swallow the scraps.

“Give it up, Thorn!” they roared. “Open your mouth!”

The denizens of Murderers Row eagerly lined their cell doors, watching Thorn’s eyes and face bulge; he was propelled backward over his cot until his head hung upside down, and Sheriff Doht pried his jaws open and reached into his mouth for the chewed scraps of paper. Jarvis at last released his grip on Thorn’s throat, and the prisoner gasped in long drafts of air.

The fragments bearing Thorn’s writing were reassembled on a table in District Attorney Youngs’s office:

Some attending Journal reporters quickly translated it:

My dear—you wrote of self-destruction. That would be best. I had thought it over long ago and came to the conclusion that it would be best for me, but not before all is done to gain liberty. Perhaps it will be the better way, and I will, and it will be easy to accomplish it. I have a prescription for morphine that I can buy or get at any drug store. But have patience and endurance and say what I write to you. If it comes to extremes, then it is time, and I will arrange it so. It is not on account of living that I would like to get free, but to spite the people here.

The watch on Thorn’s cell was instantly doubled, and his sister and brother-in-law were searched carefully whenever they entered the facility. As the only visitors Thorn deigned to see, they were almost certainly part of his plan for obtaining the morphine overdose.

“I am sorry,” DA Youngs sighed. “The Journal did not give me Mrs. Nack’s original letter. No scrap of her note has been found. He either threw the letter down a sink or tore it into fragments and swallowed it.” The Hearst reporters shrugged it off; Doht’s lousy security at the jail wasn’t their problem.

“Bring the sheriff here,” snapped the DA to a detective.

Sheriff Doht, led into the office, stammered out an excuse: Nack’s letter was surely a fabrication by a German-speaking prisoner in the jail, or by the Journal itself.

“I don’t blame you boys,” he leered at the reporters. “I understand how you work.”

The Hearst men scoffed at him; Doht just wanted to cover up his own missteps, which had been piling up. He had tried to induce vomiting in both prisoners by filling their soup with grease, with the ridiculous notion that he’d extract confessions out of them while they retched; then he’d hung a picture of a man’s disembodied head over Mrs. Nack’s cot while she slept. DA Youngs was unamused, and the sheriff quickly backed down.

Confronted at her cell, Mrs. Nack also tried denying the note—“Oh, my God, I never write such a letter!”—before breaking apart in fury when the text was read back to her.

“To whom did you give the letter?” she was asked.

“Rockaway,” she spat in disgust.

What kind of a world was it when you couldn’t trust a jewel thief?

JOURNAL REPORTERS SWOOPED DOWN into Hell’s Kitchen and up the block of brick tenements past the corner of Forty-Second and Tenth—past Stemmerman’s grocery, past Mssr. Mauborgne’s Mattress Renovating, past a stable and the neighboring blacksmith shop—and piled into the five-story walk-up at 521 West Forty-Second.

Where’s Guldensuppe’s head? they demanded.

Standing in the doorway was Paul Menker, a local butcher now better known to the world as Martin Thorn’s brother-in-law. “I know nothing about this case at all,” he said flatly to reporters.

Where’s the head?

“Anybody who tries to drag me into it will get hurt,” he said, his voice rising.

Come now, the reporters pressed—we have his confession.

Menker was enraged.

“I know nothing about the case,” the mustachioed butcher sputtered, before reaching for a rather unfortunate turn of phrase. “Bring a man that says I do, and I’ll knock his head off!”

Excellent; the Journal reporters made sure they got that quote down. They were on a roll, for their rivals at the World had fumbled yet another a priceless lead. The same day that the Journal revealed the lovers’ suicide letters, Pulitzer’s team had landed a tantalizing story: that one Frank Clark had heard a boozy confession back in late July. While laid up in the Tombs infirmary, Clark had been prescribed bitter quinine for his malaria, along with a ration of at least three shots of whiskey to wash it down. He wasn’t a drinking man, though, and each day he gave his drams to the man in the next bed—Martin Thorn. Warmed by his first liquor in weeks, his neighbor talked about the mysterious fate of William Guldensuppe.

“He often boasted,” Clark recalled, “that he was impossible to convict without the head.”

And Thorn kept talking, lulled by the seeming nonchalance of his new friend. Clark was a talented forger—he could draw an exact replica of a dollar bill with nothing but a green pencil—but the man was no killer. What Thorn confessed next preyed on Clark’s mind for months until he finally gave a 3,500-word affidavit to the district attorney.

“He told me that after he placed Guldensuppe’s head in the plaster of paris, he threw it in a patch of woods,” he testified. “He told me Gotha had erred when he said the head had been thrown into the East River. Thorn said he told Gotha it was his intention to so dispose of the head, but he was frightened off.”

The attention being paid to the ferries and riverside in the days after the murder was discovered, not to mention the Journal hiring grapplers out on the river, simply made it too perilous for Thorn to come out of hiding to finish the job. Arrested with the head still on dry land, though, he’d found an even better solution.

“Two weeks after Thorn’s arrest a man came to the Tombs to see him,” Clark continued. “This was on July nineteenth.”

It was on that visit, Clark said, that Thorn told his visitor exactly where to find the head. His accomplice promptly located it, packed the heavy chunk inside a tackle basket, and that very afternoon boarded a fishing excursion vessel, the J. B. Schuyler. With his rod and tackle, he didn’t stand out from the other leisure fishermen on the side-wheel steamer. As the Schuyler floated among the fishing banks miles offshore, Thorn’s accomplice simply tipped his basket’s parcel into the water. Two days later, he returned to the Tombs to report the good news. “Thorn was very happy,” Clark reported.

A visit to the ailing forger by the district attorney left prosecutors convinced of his story—but they refused to give the World the identity of Thorn’s accomplice. And there things sat for the next six days, without much follow-up by Pulitzer’s reporters—until the Journal came piling into Menker’s hallway.

Is it true? Did you really do it?

Mrs. Menker, Thorn’s sister, tried to fend off the reporters. Her husband was a good, hardworking man, she explained, and didn’t know anything about the case.

Doesn’t the prison record show he visited Thorn on the nineteenth and the twenty-first?

Paul Menker was a decent man, the wife insisted—and, she added, he will throw you down the stairs if you don’t leave us alone. The Journal reporters quickly retreated, leaving the butcher quaking with anger.

“I tell you that Guldensuppe is alive!” he roared after them. “That Thorn is innocent! That Guldensuppe will be found!”

IN FACT, one official was wondering whether he just might be right. A letter had arrived in Coroner Hoeber’s office back in early August, from a woman claiming to be the wife of an attendant at the Murray Hill Baths:

I cannot any longer keep quiet. Guldensuppe lives and keeps silent simply out of revenge against Thorn, of whom he is insanely jealous. He will only appear after Thorn has been sentenced to death. If the police would only look around Harlem they could easily find Guldensuppe. More I dare not say.

Respectfully,

MRS. JOSEPHINE EMMA

Hoeber’s staff was marveling over the newly arrived letter when they looked up to see an unannounced visitor peering at it: Mrs. Nack’s lawyer, Manny Friend.

“I intended not”—the angry coroner slipped into his native German syntax—“that you should see that letter!”

They were old enemies, and Friend instantly accused the coroner of holding out evidence on him. Hoeber, the lawyer yelled, was “a dirty, insignificant little whelp.” The two scuffled, and Hoeber’s staff dragged them apart. Maybe the coroner wrote the letter himself to get attention from reporters, the lawyer yelled. “I believe,” he jeered, “that he has resorted to this method to gain a little more advertisement for himself.”

If so, then Hoeber was going through a lot of ink. A cascade of mysterious and often unsigned confidential letters now arrived at his office. One claimed that it was Guldensuppe who’d been hiding in the closet waiting to attack Thorn—and that he’d been killed in self-defense. At least two more claimed that Guldensuppe was alive and well, and seeking out his fortune prospecting in the Klondike.

The accused himself insisted that he’d be vindicated.

“I have always believed that he had gone to Europe,” Thorn assured a World reporter about yet another Guldensuppe sighting in Syracuse, New York. “I am sure he will turn up in time to clear me of the charge of murdering him.” Perhaps it was just as well that the reporter did not note that his own paper attributed the latest sighting to a Mr. “O. Christ.”

Soon enough, another letter insisted that everyone else was wrong:

Kindly do not believe any of the cards being sent to you saying that Guldensuppe lives yet, as he does not. He was murdered at Woodside, L.I. and the head you can receive by looking sharp at the Astoria Ferry pier about near the point of the Ninety-first street dock.… Will let you know more. The party that killed him does not know that I saw this.

Yet another missive, sent by Mrs. Lenora Merrifield of 106th Street, claimed that Guldensuppe was working under an alias in a Harlem barbershop. When confronted by detectives, a puzzled Mrs. Merrifield didn’t even recognize the letter; her teenaged son, however, showed a peculiar interest in the commotion it created.

But the most haunting notes were the anonymous ones penned in German and sent to Coroner Hoeber: Guldensuppe is alive, and taking revenge on Thorn by setting him up to die. No stock could really be put in these wild and unsigned allegations. But if William Guldensuppe was plotting retribution, it seemed he was about to get it: Thorn’s trial was now set for October 18.

“THE POLICE DO NOT EXPECT to see Guldensuppe in this world,” William Randolph Hearst joked. “In fact, they would be content to see his head.”

It had been a splendid season for news. Along with this swell murder here in the north, Hearst also had a huge promotion to send a team of Journal cyclists eastward to Italy, an exciting gold rush out west, and from the south a bubbling Cuban rebellion against the dastardly Spanish. The latter had acquired a fine new angle over the summer: Evangelina Cisneros, the pretty eighteen-year-old daughter of a revolutionary, had been imprisoned for … well, depending on whom you asked, either for trying to break her father out of jail or for fending off the advances of a diabolical Spanish military governor. Hearst preferred the latter explanation.

Even as he sent reporters to run the gauntlet of Paul Menker’s stairs, he’d sent another Journal operative—the hotshot reporter Karl Decker—to Cuba, to bribe a jailer, break into the prison with a ladder and a hacksaw, and chop out the iron bars of the damsel’s jail cell. Disguised with a sailor’s outfit and a cigar, “the Cuban Joan of Arc” was whisked away on a steamer bound for America. EVANGELINA CISNEROS RESCUED BY THE JOURNAL, his newspaper trumpeted the next day.

The rescue was not exactly legal. But Hearst was always pushing for more: Why just cover news when you could make it?

A NEW IDEA IN JOURNALISM, the Journal blared across a full-page illustration of a knight slaying octopus-like beasts: WHILE OTHERS TALK, THE JOURNAL ACTS. The paper was already launching city offensives against a gas trust and crooked paving contractors; now it would also shake the columns of national policy. Hearst lined up testimonials from the mayors of cities from San Francisco to Boston lauding his juggernaut, and even Secretary of State John Sherman delicately acknowledged the paper’s rather tactless achievement. “Every one will sympathize with the Journal’s enterprise in releasing Miss Cisneros,” he admitted. “She is a woman.”

The prime minister of Spain was more direct.

“The newspapers of your country seem to be more powerful than your government,” he snapped.

Hearst was inclined to agree: The Guldensuppe case had paved the way for his paper to take it upon itself to shove aside any government, local or national, that moved too slowly to satisfy a pressroom deadline. The Cisneros rescue simply confirmed what he’d been claiming all summer.

“It is epochal,” he announced from his office overlooking the city. “It represents the final stage in the evolution of the modern newspaper. Action—that is the distinguishing mark of the new journalism. When the East River murder seemed an insoluble mystery to the police, the Journal organized a detective force of its own. A newspaper’s duty is not confined to exhortation, but that when things are going wrong it should set them right if possible.”

He could afford to feel expansive in his powers, for his powers were expanding. The old order was literally falling away: Sun publisher Charles Anderson Dana was now on his deathbed, and Pulitzer’s World was getting clobbered in the Guldensuppe case and in Cuba coverage. Journal sales were rocketing; a reader snapping it open to the latest revelations from Woodside or Havana would find them alongside a fine profusion of ads for everything from the Bonwit Teller department store to Seven Sutherland Sisters Scalp-Cleaner, or perhaps the Lady Push Ball Players—lasses in short garments who fought gamely over a giant medicine ball.

All this was laced with Hearst’s own grand promotions. Just a day after raiding Thorn’s brother-in-law’s premises, Hearst was issuing new marching orders: Pull out all the stops for the arrival of Evangelina Cisneros.

“Organize a great open-air reception in Madison Square. Have the two best military bands,” he barked to his managing editor. “Secure orators, have a procession, arrange for plenty of fireworks and search-lights. We must have 100,000 people together that night.” Rooms were hired at the Waldorf, reservations made at Delmonico’s, and launches arranged to greet the bewildered ingénue as she arrived in New York Harbor. The story would then be splashed across the October 18, 1897, Journal—on the very day, in fact, that Martin Thorn’s jury selection would begin. The New York Journal would yet again own the biggest local, national, and international stories for that day.

The World, one industry newsletter marveled, was now simply “scooped every day of its existence.”

The paper wasn’t just getting scooped, it was also getting hollowed out. Its star editor, Arthur Brisbane, was nettled by ceaselessly hectoring telegrams that Pulitzer sent from health retreats. In one the publisher cabled, THE PAPER SUFFERS AN EXCESSIVE STATESMANSHIP, yet in another he demanded the firing of a reporter for using the word “pregnant.” He was stingy about the expenses for art—MAKE SALARIED ARTISTS EARN THEIR SALARIES, he warned—yet he kept constant tabs on the editorial page, perhaps the least commercial section of the paper. Just about the only relief the absentee owner’s daily cables offered was this one: I REALLY DON’T EXPECT TO BE IN NEW YORK AT ALL THIS FALL. In fact, the World was perfectly capable of running without Pulitzer; instead, it would have to run without Brisbane, who jumped ship for the Journal. All it had taken, as usual, was a wave of Hearst’s checkbook.

But amid these triumphs, just three days ahead of Thorn’s jury selection, it was the Brooklyn Eagle—not the Journal—that carried the first word of a curious development in Germany. The call for jurors, it seemed, would have to wait: Carl and Julius Peterson, two “reputable merchants of Hamburg,” were departing for New York via the ocean steamer Fürst Bismarck to personally testify about an unexpected old acquaintance they’d just recently run into.

The Eagle headline said it all: