A single conversation across the table with a wise person is worth a month’s study of books.

Chinese Proverb

The benefits of collaborative practices are well established, yet impediments to consistent and meaningful professional conversations and other collaborative opportunities regarding instruction for ELLs persist. Lack of time is often cited as a major factor, which prevents teachers from exchanging ideas, jointly planning lessons, evaluating individual student progress on a regular basis, and discussing appropriate interventions. This chapter will identify time frames in which collaboration among teachers can take place successfully. We will examine favorable occasions already built into current schedules as well as offer sample templates to consider and schedules for a range of collaborative practices including co-teaching. We will conclude with suggestions on how to ensure adequate time for collaboration and co-teaching.

On a Wednesday afternoon, the clock in the main lobby of De Salle Middle School strikes three as the dismissal bell simultaneously rings. Swarms of young teenage students file out the lobby doors and climb onto school buses for their short journey home. In the midst of the clamor, Mr. Timothy, a veteran ESL teacher, makes his way toward the school library where he will join his colleagues for their usual Wednesday afternoon grade-level meetings.

Mr. Timothy finds the table where his fellow ESL colleagues are seated and sits down just in time to hear his new principal outline what needs to be accomplished at this afternoon’s meeting. The principal directs grade-level teams to set their own agendas, record their meeting’s minutes, and submit their minutes directly to her by week’s end. After she assigns subject specialists to grade-level teams, the principal wishes everyone a good afternoon and makes a hasty retreat.

Groups of teachers file out of the library and settle into separate meeting spaces throughout the building. Mr. Timothy joins a sixth-grade interdisciplinary team that has entered a small classroom across the hallway. Immediately, the English language arts teacher takes charge and suggests topics that should be covered. Several people nod their heads in agreement, and the discussion begins.

The group exchanges ideas about standardized-test preparation, parent-teacher conference schedules, and report card comments. When report cards are discussed, Mr. Timothy takes the opportunity to speak up about the lack of grading policies the school has for ELLs. His concerns stem from the inconsistent manner in which ELLs are assessed and their progress is reported to parents. It seems as if some students are graded with their current language-proficient abilities in mind while other ELLs’ progress is reported using the same criteria as the general-education students in their classes.

As Mr. Timothy begins to outline some of his ideas for improvements in the grading system, the science teacher quickly interrupts him. She notes that grading policies are beyond the scope of their meeting. Although she and others on the team sympathize with Mr. Timothy’s concerns, the science teacher refocuses the discussion on the next agenda item.

As our vignette illustrates, in order to accomplish effective communication among its members and make the most of available time, collaborative teams need to establish goals, a clear purpose, and guidelines for their operation. Agendas need to be set with all members in mind and conversation protocols developed so that member focus remains on the issues. These groups also need administrative support to schedule the necessary time to accomplish their objectives in order to produce the intended outcomes.

The setting of interdisciplinary teams for the purpose of collaboration is a worthwhile goal for schools and districts to pursue. These cross-subject collaborators generally consist of teams who teach the major content areas of the school curriculum or are a combination of grade-level teachers and subject specialists (ESL, literacy, technology, etc.). Teachers working in these groups share essential information about their teaching craft along with skill and content objectives that can be carried across the curriculum to enhance the continuity of instruction. In this way, ELLs can be exposed to a wide range of educational experiences all aimed at the same objectives.

Members of any collaborative team need to develop cooperation and a shared interest in the group’s collective purpose. Participants, be they core-subject, generaleducation classroom, or special-subject teachers, should be on an equal footing when it comes to agenda setting and group discussions. When given the opportunity to meet, administrators and collaborative teams must pay careful attention to how meetings are structured in order to make the best use of allotted time and to ensure that all members have an equal say in sharing their concerns, ideas, feelings, and personal beliefs.

In our opening vignette, Mr. Timothy and his fellow subject specialists did not have the same status as the other members of the interdisciplinary team. Core members of each team had already been established and were permanent members of a collaborative group, whereas subject specialists were just visiting respective teacher groups.

It is a common occurrence for special-subject teachers not to be included as permanent members of interdisciplinary teams. Administrators view this practice advantageously; it allows various teams the time and opportunity to have the counsel of different specialists that rotate in and out of different team meetings throughout the school year. Besides, the number of ESL teachers per school is often small, which creates challenges for administrators when assigning them to permanent interdisciplinary teams. A critical recommendation we have is to make sure ESL specialists are accepted and valued as contributing members of all school-based teams and professional groups and, as such, are fully included in collaboration at an established time and place. Several issues arise from the practice of assigning nonpermanent members to teams. First and foremost, it does not allow teacher specialists to bond with other members of the team. According to Levi (2007), participants in any collaborative effort need to develop some level of personal relationship with each other in order for good communication and trust to occur. When social relationships are lacking between group members, communication can break down. Rotating between teams does not allow specialists to form strong relationships or afford the opportunity to develop trust. In turn, communication is negatively impacted and specialists’ ideas and concerns minimized.

When special-subject teachers float between teams, they are perceived as guest participants and not as full members of the team. Teacher specialists may be marginalized in these collaborative meetings. The regular group members may use teacher specialists as a resource for information when they need clarification about a discussion issue, yet they do not expect them to fully participate as other members of the group do.

Another problem that arises from this scheme is that rotating team members may be underused. The valuable expertise of ESL teachers and other specialists regarding youngsters with exceptional needs may not be not given a voice during team meetings, which leaves classroom teachers, already challenged with the education of these pupils, without needed support. Additionally, when the knowledge of specialists is not shared, teachers restrict the scope of their collaborative meetings and reap fewer benefits from their teams. It is important to establish equal status among all participants and to give their ideas and opinions equal weight.

Before administrators can plan sufficient time for teachers to meet, the purpose of collaboration must be identified and carefully discussed. Most often, teachers cite the need to exchange their views on the nuts and bolts of lesson planning and student instruction with each other, as well as day-to-day organization and classroom management they commonly share. However, collaborative topics are much broader than classroom practices. They encompass a whole host of educational objectives that can be used as building blocks to transform a school culture. Before setting time frames for collaborative work, the rationale for collaboration must be identified. Once the purpose is set, a time frame for collaborative activities can be established.

Certain collaborative activities easily lend themselves to having a set beginning and end. These types of collaborative practices are for the purpose of establishing a basis for an overall shared mission or vision for ELLs, to develop a common understanding of general information about English learners, or to decide the future goals for particular content curriculum, grade levels, program models, or school resources. These collaborative activities may involve the whole faculty as well as the support staff so that everyone can have a common perception of instructional data regarding the education of ELLs.

Finite collaborative practices may include broad topics such as the following:

Finite collaborative activities also may include small-scale ideas such as the following:

Small-scale information usually is shared during teacher preparation periods, lunchtime meetings, or brief hallway conferences. In contrast, broad-based finite collaboration often is accomplished during general faculty meetings or days specifically scheduled for staff development. An outside expert may even be invited to conduct a series of workshops for a large-scale or select group of faculty to outline and clarify collaborative practices. Targeted professional development for specific purposes can be the stimulus for meaningful change in teaching and learning if the right approach is taken.

AN EXAMPLE OF FINITE COLLABORATION

Collaborative Task: ESL Program Revision in a K–12 District

Who is involved?

An eclectic team consisting of building and central-office administrators, elementary classroom and special-subject (art, music, etc.) teachers, ESL specialists, middle and high school content-area teachers, special education professionals, social workers, and outside consultants will participate and contribute ideas regarding programs for ELLs.

What are the team’s short-term goals?

The team will strive to understand the challenges of ELLs in the general-education classroom, identify the district’s current programs for ELLs, review assessment and other pertinent data to outline the strengths and limitations of the district’s programs, and identify programs and broad-based strategies to help meet the needs of the ELL population. The following are the team’s guiding questions:

What are the desired outcomes?

Through collaborative efforts, the team will decide on three long-term goals for the coming school year, determine how each goal will be evaluated, and identify any necessary professional development or resources to accomplish established goals.

When and where do meetings take place?

Meetings are scheduled when school is not in session. Approximately 20 hours of commitment is necessary to accomplish the task. Participants are remunerated for their time.

The characteristics of ongoing collaboration require continuous and planned opportunities for teachers and administrators to engage in meaningful dialogue about instruction and student learning. The need for this type of consistent practice is embedded in the nature of the perceived or desired outcomes. Whether teachers are engaged in co-teaching ELLs, in-class coaching, mentoring new teachers, reciprocal classroom observations, or specific teacher study groups to increase understanding of ELLs, continuous collaborative effort is necessary to implement these innovative practices successfully.

The main challenge of this kind of collaborative effort is that a great deal of time is needed to plan and share with colleagues, much more so than with finite collaboration. Some schools have built time for collaboration into daily class schedules. Teachers are grouped into teams, often in one of the following configurations1:

The following are various types of information teams may share about co-teaching, curriculum, and instructional strategies for ELLs in collaborative groups:

Contractual issues prevent some school districts from altering teachers’ schedules in order to produce effective ongoing collaboration. Other districts do not want to change the amount of teacher contact time with students in order to schedule collaborative team meetings; administrators often are concerned with not having community support for this practice. Yet, schools that value collaborative practices find creative ways to schedule meetings in already overburdened schedules. Whatever the case, a specific framework for structured and reoccurring meetings allows teachers to engage in dialogue in the most meaningful ways for their students. Table 6.1 illustrates the key components of an ongoing-collaboration framework.

| Table 6.1 | Framework for Ongoing Collaboration |

Ongoing collaboration should encourage teachers to reflect upon their current practices. The process of reflection allows teachers to revisit what they have learned, share their experiences with their colleagues, and obtain insight into their own teaching (practices) by continually evaluating what is done in the classroom to assist English learners.

Teams involved in collaborative practice should include periodic reflection. This type of evaluative process can be accomplished through developing, discussing, and answering key questions regarding classroom instruction for ELLs. Some questions that may be helpful for reflection are as follows:

Since reflection is an essential component of both self-assessment practices and formative assessments, we will more fully explore it in Chapter 8.

AN EXAMPLE OF ONGOING COLLABORATION

Collaborative Task: Planning Interdisciplinary Instruction for ELLs in Grade 6

Who is involved?

An interdisciplinary team consisting of core content-area teachers (English language arts, math, social studies, and science) and an ESL specialist plan thematic units to benefit ELLs.

What are the team’s prevailing goals?

The team’s purpose is to plan interdisciplinary instruction on an ongoing basis. Necessary goals will focus on the following:

What are the desired outcomes?

Considering thematic instruction is an important key to English learners’ academic success (Freeman & Freeman, 2003). An increase in English learners’ adequate yearly progress (AYP) is desired. Additionally, the ability to identify successful units and retain them for future use is a suitable aim.

When do meetings take place?

Meetings are scheduled during a weekly congruent planning period. School schedules should be devised so that all ELLs in Grade 6 are able to work with the interdisciplinary team creating thematic units.

We have observed numerous groups of teachers working collaboratively to plan lessons for ELLs. One group of third-grade teachers in cooperation with their shared ESL teacher had a unique way of developing instruction for their students. They formed a group that met during a specially scheduled time for one period each week with the expressed purpose of planning differentiated learning for all their students.

This team of teachers arranged themselves in front of a bank of computers. A five-minute brainstorming session elicited numerous topics and a theme was chosen by consensus. At that point, the members of this group assumed different roles. The classroom teachers took on the positions of leader, reporter, and clarifier of content-area instruction. The ESL teacher acted as the in-house expert on materials and strategies for ELLs.

The lead teacher used a checklist of the different elements necessary for the selected theme, the reporter keyed the information on the computer, and the clarifier identified standards, literature, and other materials as possible resources. The ESL teacher took notes, suggested ways to organize the theme components, determined activities that were appropriate for the different language proficiencies of the group of third-grade ELLs, and explained that she would need more time to devise some activities according to specific content.

These collaborative partners seemed to take their job seriously. They remained focused on their lesson-writing task and used a common lesson plan format. This team complained little, refrained from personal discussion, and incorporated humor to keep their spirits up. Each team member carefully debated how to present the theme’s topics using appropriate strategies and resources for ELLs. These teachers actually engaged in conversations about their students’ abilities, tried to match activities that were appropriate to each level of instruction, and remained on task until the lesson plans were completed.

We observed a second group of teachers faced with the same task, to develop lessons that incorporated differentiated instruction for their students. This group of teachers included three kindergarten teachers, an ESL teacher, and a student teacher. The teachers also began by sitting at a bank of computers while the student teacher sat apart from them. They both individually and collectively looked through various file folders, and they expressed their concerns about duplicating copies of student handouts for future class activities while engaging in various discussions other than lesson planning.

The teachers’ topics of conversation ranged from housekeeping issues such as “Healthy Snacks Week” to curriculum activities such as events for Dr. Seuss’s birthday. They rapidly moved from topic to topic, and their conversations thoroughly engaged everyone in the group. During a brief pause, one teacher turned to us and said, “Now this is collaborating.” After approximately 15 minutes, the teachers focused on creating the differentiated lessons they were charged to do.

The group tried to search for previously written lessons, but after another 15 minutes had passed, they could not find them and decided to proceed without them. One teacher commented, “Lessons in math are already differentiated in the math text.” The teachers moved forward in the planning process by individually searching through the math text for possible lessons to adapt.

The teachers engaged in personal discussions about other faculty members. They used an established format for writing collaborative plan summaries on the computer to copy a lesson from the math book. With 10 minutes left in the session, the teachers shared with each other ways to differentiate the established math lesson. As the session ended, the teachers’ discussions again steered away from lesson planning. A variety of topics captured their individual attentions and amused them: from the way one eats a Reese’s Peanut Butter Cup to what is entailed in incubating eggs in the classroom.

In both the kindergarten and third-grade groups, the teachers had established strong relationships among their peers. Each teacher seemed to accept the other for her contributions and role in the process. These teachers had the ability to console and amuse one another, and each exhibited trust in her colleagues. Yet, one set of teachers was better able to focus on its intended planning task while the other eventually accomplished its prescribed goal but in a more superficial way.

Although it appears that collaborative conversations may be effective in some situations, one cannot suppose that just providing the necessary time for professional discourse leads to desired outcomes. The problem some teachers face with the collaborative process may stem from the manner in which collaboration itself has been implemented. Change is a complicated issue, and although the purpose for collaboration may be set, the means for accomplishing its intended outcomes often are not. According to Fullan (2007), teachers not only need to understand the need for improved practices, they must also have a clear understanding of the beliefs and practices they are asked to implement. Participation in the collaboration process is no different. Without a clear understanding and a strong buy-in to its purpose and beliefs, teachers will focus on superficial goals to satisfy an administrative directive instead of engaging in activities that are meaningful to the group as a whole.

There may be many obstacles to overcome to ensure teacher collaboration yields desired results. Some of these barriers have to do with a teacher’s status in the school community. Inger (1993) discusses how teaching certain disciplines—such as core academic content—commands greater respect in the school community compared with others who are less valued because they work with special student populations. Other barriers that impede collaboration include departmental walls, physical separation due to allocated space or program scheduling, and concepts of teacher autonomy (Inger, 1993). How then do we identify the qualities that take these collaborative conversations to the desired level of transformative learning for teachers and thereby their students? And what if time is the major obstacle to effective communication among teachers?

Engaging in productive conversations with colleagues can be frequently hindered by time. One way to make the best use of allotted time to discuss workplace issues is to use specific formats for structured conversations that allow for a clear, common focus of discourse and provide guidelines for all members’ participation. These conversation protocols facilitate a balanced approach, allowing all members to be actively involved in the decision-making process by bringing a diversity of voices and opinions to bear on issues that require it (Garmston, 2007).

Conversation protocols can be very specific in how they guide the course of a discussion by identifying each group member’s time frame for speaking and the precise subject matter to be addressed. Staying within the protocol’s framework can help assure collaborative partners that each member will be heard and prevent conversations from going off on tangents. Various types of structured conversations can help generate ideas and provide a means for collaborative groups to interact and reflect on their practices. Table 6.2 is an example of a conversation protocol that can be used for co-teaching partners to reflect on their classroom practices.

Even if you have been a collaborating partner, or co-teaching for a long time, each new school year brings its new and unique challenges. Teachers change grade levels, retire, are reassigned to other schools, or are no longer employed with the district due to budget cuts. New curriculum and special programs are adopted or assessment/evaluation methods, government standards, and state regulations are revised. These events and policies lead ESL teachers to forge new relationships or begin needed conversations with additional colleagues to strategize and plan for ELL instruction. Conversation protocols can be a useful tool to further the progress of these important dialogues. Table 6.3 illustrates the many conversation topics that can be facilitated by conversation protocols for newly formed or ongoing collaborative or co-teaching partners.

| Table 6.2 | Protocol for Collaborative Professional Conversations on Co-Teaching |

Adapted from Easton, L. B. (February/March 2009). Protocols: A facilitator’s best friend. Tools for Schools, 12(3), 6.

| Table 6.3 | Conversation Protocol Topics to Enhance Instruction for ELLs |

| Categories | Subareas |

| 1. Use of Teaching Strategies | Lesson structure Questions Examples Teaching aids Group learning Reinforcement |

| 2. Engagement | Learner attention Learner background knowledge and life experiences Learner interest |

| 3. Lesson Content | Clearly identified concepts Clear distinction between concepts and illustrations Appropriate level of complexity |

| 4. Classroom Management | Variety of control techniques

Use of students in administrative tasks |

| 5. Trial-and-Error Learning | Appreciation of mistakes Openness to student correction Sufficient repetition |

| 6. Classroom Environment | Joy Order Best use of facility |

| 7. Language Skills | Clear pronunciation Appropriate vocabulary level Effective communication |

| 8. Evaluation | Modification in lessons based on real-time experience Awareness of learners’ success or failure Assistance to weak students Interventions |

| 9. Administrative Issues | Record keeping |

Adapted from Allen, D. W., & LeBlanc, A. C. (2005). Collaborative peer coaching that improves instruction: The 2 + 2 performance appraisal model. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin. (pp. 76–77)

According to Love (2009), teaching can be divided into three parts—lesson planning, delivery, and personal reflection. However, time for planning and reflection, as a part of ongoing practices with colleagues, is minimally scheduled into the school day. Administrators as well as other stakeholders view student-teacher contact time to be the key for increased academic success among pupils and believe “if teachers are not in front of students, they are not doing their job” (Love, 2009, p. x). Yet, a growing number of research studies indicating positive relationships between teacher collaboration and increased student achievement (Goddard, Goddard, & Tschannen-Moran, 2007; Louis, Marks, & Kruse, 1996) are beginning to lay the foundation for a change of attitude toward collaborative practices.

In our own discussions with a variety of educators, teachers frequently reported that the regular school day is the best time to collaborate with their fellow teachers and that their teaching schedules should reflect formal opportunities to work together. ESL teachers throughout the United States have shared with us that they conduct most of their planning with classroom teachers informally—in the hallway, in the classroom when children are engaged in an activity, while warming lunch in the teachers’ lounge, or waiting to use the rest room. They have also revealed that when they have had formal opportunities to collaborate, their efforts have resulted in more successful lesson delivery in a variety of classroom settings for English learners.

Although several obstacles can challenge teachers who are interested in coordinating their instruction or developing co-teaching lessons for ELLs, the most pressing one is a lack of time to implement collaboration and co-teaching schemes. When administrators do offer teachers time for collegial conversations, these discussions usually occur at the end of the school day when most faculty meetings are scheduled. Not only are teachers tired from their day’s work, but most people’s energy levels are the lowest in the late afternoon (Dunn & Dunn, 1999). This causes many participants to have a let’s just get this over with attitude, and the overall quality of planning for ELLs can be greatly reduced. Not having planned time during the school day can soon quell teacher enthusiasm and prevent the enhancement of instructional routines, settings, resources, and strategies to benefit ELLs. Table 6.4 suggests ways to facilitate scheduled time for collaborative teams to meet.

| Table 6.4 | Creating Opportunities for Teachers to Meet During the School Day |

Sources: Love, 2009; Villa, Thousand, & Nevin, 2008

Vignette Revisited

Mr. Timothy sits quietly for the remainder of the meeting with his colleagues. After the meeting ends, the science teacher approaches him and begins to apologize for her earlier interruption. She says she understands his concerns and frustrations, but she and her fellow teachers who must instruct students in the content areas where state assessments are an issue must discuss many other matters. Unfortunately, the time they have together is short, and their agenda usually is too long.

It is apparent that Mr. Timothy is not considered an equal partner during this group’s collaboration time. This problem may stem from his purpose being finite in a collaborative effort that is ongoing. Because specialists are rotated between different interdisciplinary teams, this ESL specialist is not perceived as a vital contributing member. Since Mr. Timothy is not a constant factor in the group, the team still functions more or less with or without his input.

In order to improve the equity in collaborative practice and to solidify both generaleducation and ESL teacher expectations for its practice, all participants must have the DESIRE to make collaboration work.

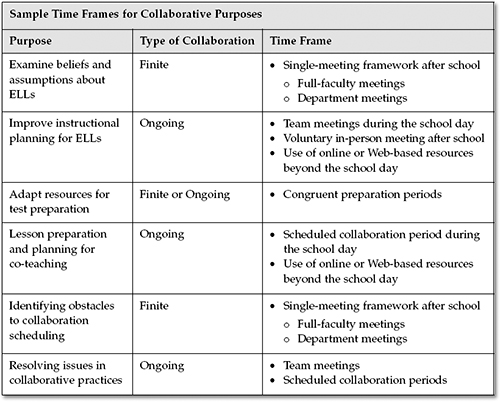

When the purpose and expectations for collaboration are set, administrators and teachers can develop time frames for collaboration to take place. Table 6.5 illustrates various topics for teacher collaboration accompanied by possible time frames to accomplish the task.

| Table 6.5 | Identifying Time Frames for Teacher Collaboration |

At times, administrators who want to foster collaborative environments will elicit from their faculty ideas to produce the needed time frames for collaborative practices. Unfortunately, not all teachers view collaboration in a positive light, and some may seek to create impediments to prevent the establishment of specific schedules for meetings to take place. Based on our conversations with both ESL and classroom teachers, the following are some of the possible roadblocks to setting collaborative time frames:

For a growing number of ESL and general-education teachers who co-teach or would like to adopt a co-taught or inclusion model of instruction, scheduling is one of the many variables to be addressed for the successful development of language acquisition, literacy, and content-area subjects with English learners. Adequate time must be designated during the school day to accomplish co-teaching goals. Furthermore, if ESL classes are to be taught using co-teaching models, administrators and teachers must take into account the age of the students, the set-up time each lesson entails, and the time of day for instruction that would most benefit ELL students.

Scheduling begins with the building administrator creating a master plan, and the rest often depends upon the grade level of the students. For elementary-level teachers, time frames for ESL classes are organized around general-education class schedules that frequently include block time for literacy and mathematics as well as lessons outside the regular classroom in music, art, technology, etc. Many ESL teachers are responsible for setting up their own schedules and must navigate within the confines of each class’s program timetable to arrange their own ESL sessions.

For middle and high school classes, separate ESL instructional periods are usually written into the overall master schedule. However, if co-teaching models are used exclusively, there is no longer a need to schedule separate periods for ESL. Table 6.8 illustrates a sample schedule on the middle-school level for an ESL teacher to co-teach core subjects in general-education classrooms without separate periods designated for ESL. In any case, whether or not ESL co-teaching is conducted throughout the day or used on a part-time basis in combination with a pull-out or regularly scheduled period of ESL instruction, administrative support is essential for co-teaching schedules to be established.

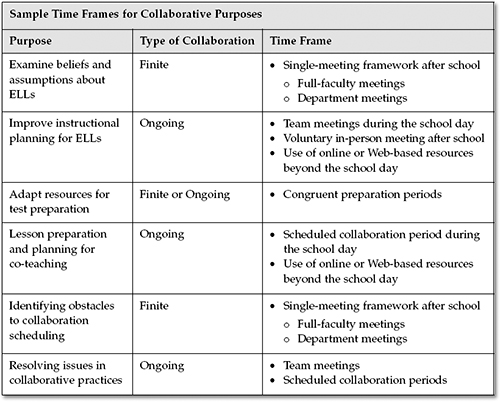

ESL co-teaching can be successfully accomplished using a part-day schedule. In this teaching scenario, the ESL teacher spends part of the school day co-teaching with one or more general-education teachers, and the rest of the day is devoted to pull-out or regularly scheduled instruction for ELLs. Table 6.6 identifies a combination co-teaching/pull-out schedule for an elementary ESL teacher who is responsible for ELLs in Grades 3 and 4.

In our illustrated schedule (Table 6.6), the first period is set aside for collaboration with the different Grade 3 and Grade 4 team levels on alternate days (Monday–Thursday) before the start of daily instruction; the fifth day (Friday) is designated for departments such as ESL or grade-level teachers to meet as separate teams. Each morning is divided into two periods of back-to-back instruction for each grade level serviced. The afternoon hours are designated for small-group instruction in a separate classroom setting with a select group of ELLs. The last period of the day is an individual preparation period for the ESL teacher.

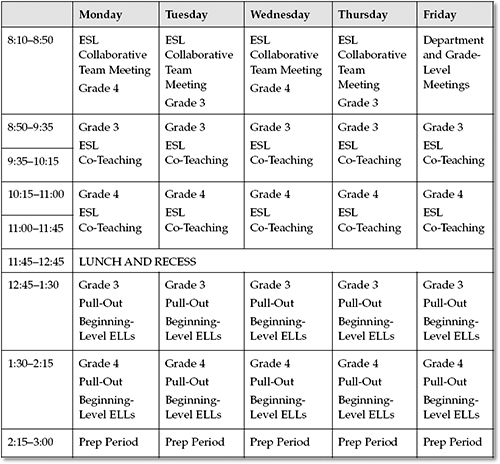

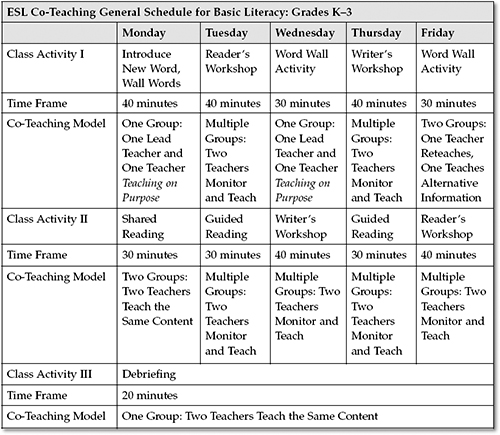

Some ESL teachers co-teach specific academic subjects in general-education elementary school classes for part of the school day. Table 6.7 on page 128 outlines literacy activities that can be co-taught in Grades K–3; it specifies a double, 45-minute period for each ESL co-teaching session; yet individual literacy activities are not 45 minutes long. The schedule additionally suggests co-teaching models to be used by cooperating teachers.

Another part-day schedule configuration involves the ESL teacher providing instruction by accompanying English learners to their core-subject classrooms. In essence, the ESL teacher spends most of the days with his or her ELLs but co-teaches with different content-area teachers. Table 6.8 on page 128 identifies a sample middle-school schedule.

| Table 6.6 | Sample Elementary School Schedule: Part-Day Co-Teaching |

Co-taught lessons may require additional planning time initially. ESL and classroom teacher teams may spend many hours planning content, creating materials, identifying models of instruction, and selecting learning strategies. However, it is as valuable a part of overall planning to jointly develop guidelines for classroom time management to ensure co-taught lessons run smoothly.

Teaching teams must estimate the time planned-learning activities will take and adhere to identified time frames as best as possible. There should be adequate time set aside for instruction, group and individual learning, student evaluation, and debriefing. It also is necessary to be flexible if certain activities take longer than originally anticipated or vice versa and alter allotted time on the spot.

| Table 6.7 | Part-Day Co-Teaching Schedule for Specific Content: Literacy |

| Table 6.8 | Middle School ESL Team Teaching Schedule: Core Subjects |

| Seventh-Grade ESL Team Teaching Schedule Monday–Friday | |

| Period 1 | Science/ESL Team Teaching |

| Period 2 | Social Studies/ESL Team Teaching |

| Period 3 | Interdisciplinary Team Meeting: ELA, ESL, Mathematics, Science, and Social Studies Teachers |

| Period 4 | ELA/ESL Team Teaching |

| Period 5 | Lunch |

| Period 6 | Lunch/Hallway Duty |

| Period 7 | Mathematics/ESL Team Teaching |

| Period 8 | Preparation and Planning |

Co-teaching partners must identify specific time management parameters and classroom procedures to facilitate co-taught lessons. Some potential topics for discussion with fellow co-teachers are the following:

When we have questioned ESL teachers regarding the need for administrative support, time and again we have heard the same concerns from many different voices:

Scheduling collaborative practices must begin with identifying an overall plan for collaborative initiatives to take place. Although the majority of teachers may be requesting time to have professional conversations with their colleagues on an ongoing basis, a building principal may not be able to meet that particular request immediately. Additionally, the desire to implement co-teaching as an innovative school practice may exist; yet, administrators may not have all the necessary resources (money, personnel, professional development, time) available to commit to such a long-term plan.

Issues beyond the control of an individual school might first need to be resolved in order for ongoing collaboration to be a part of the regular school day. Contractual and union issues are likely to be negotiated. However, several essential opportunities for collaborative practices can be put into place immediately while other initiatives are developed and implemented over time. It may take years for the desired collaborative practice to be fully developed and instituted. Nevertheless, the most important concerns for administrators to address are the focus on collaboration as a priority, the need to keep the faculty informed, and the necessary efforts to move forward with an overall plan that considers teachers’ need for time. The key features for establishing the collaboration time frame for the benefit of ELLs are as follows:

In this chapter, we have discussed challenges and presented possible solutions to find the necessary time for establishing effective collaborative practices. We have outlined specific strategies to manage time constraints by identifying the purposes for collaboration and their related time frames, creating strong team partnerships, and establishing scheduled time for both collaboration and co-teaching activities. We concluded that determining specific time demands along with accompanying resolutions will ensure the institution of regular collaborative practices and co-teaching instruction.

Center for Multilingual Multicultural Research

www-bcf.usc.edu/~cmmr/BEResources.html

The Internet TESL Journal

http://iteslj.org

TESL-EJ Electronic Journal

www.tesl-ej.org/wordpress

The University of California Linguistic Minority Research Institute (LMRI)

www.lmri.ucsb.edu

1. Adapted from Schools as Professional Learning Communities by Roberts & Pruitt, 2009 (p. 16).