New frameworks are like climbing a mountain—the larger view encompasses rather than rejects the more restricted view.

Albert Einstein

Collaborative practices require teachers to share space both inside and outside of the classroom. With twenty-first-century technology, many practitioners also make use of virtual space with online and networked tools for ongoing professional discourse. This chapter will describe the different physical and virtual environments that generaleducation and ESL teachers use in order to enhance the collaborative process. Our discussion of collaborative space will be placed within the framework of establishing and maintaining a positive, inclusive school culture. We will explore the possibilities of using formal and informal shared spaces for instructional planning and offer strategies to maximize shared classroom space for co-teaching purposes. Organizational tips and suggestions for creative classroom design and classroom management are also presented.

Sara, a veteran ESL teacher, steps into her first classroom of the morning. She is quietly yet warmly greeted by Christine, a fifth-grade teacher who is wrapping up a test prep lesson. Sara makes eye contact with two of her ELL students as she squeezes past a few seated youngsters and maneuvers to the back of the room where she stands and waits for the lesson to end. Slung over her shoulder is a large canvas bag filled with materials and supplies—pencils, scissors, glue sticks, sticky notes, mini whiteboards, erasable markers, paper, and guided reading books—to carry out the day’s lesson. Sara is also carrying her daily lessons plans, attendance logs, several teacher editions, and resource guides.

The classroom teacher, Christine, ends up going longer with her lesson than either teacher had anticipated, and Sara stands in awkward silence, not wanting to interrupt yet not knowing where to set up for the next lesson. The table and surrounding chairs that Sara is sometimes able to use are filled with students’ poster projects. But she is hesitant about rearranging another teacher’s classroom. In front of the room, Christine wonders why Sara is still standing until she notices her students’ projects spread all over the back table. She interrupts a student who is speaking and races to the back of the room, apologizing profusely while she scoops her students’ projects off the table and puts them on the windowsill. Christine’s lesson abruptly ends, and the class begins to noisily transition to the next activity (a jointly planned social studies lesson).

Even when teachers have the best of intentions, proper organization and space management are necessary for successful collaborative partnerships. Sara and Christine’s situation is an example of what might occur when teaching teams do not share the same classroom space or when teachers have not adequately planned how they will use the space they share. Other issues involving space include arranging available meeting space outside the classroom to ensure ongoing collaborative efforts. Whether it is classroom space or a place to plan collaboration, ESL and general-education teachers need to have designated areas, set meeting places that each can count on to be available for collaborative purposes.

We strongly believe that teacher collaboration is essential to all schools’ general success and especially for their English language programs that serve ELLs. Apart from careful planning to orchestrate the use of available meeting places and to organize classrooms for collaborative or co-teaching teams, schools may wish to start by examining their school culture (see Figure 7.1).

Collaboration provides teachers with a common ground for meeting the needs of ELLs. It also becomes the vehicle for change and an effective process within a school culture that supports all learners’ academic success. Moreover, teachers must believe they each have some input and influence on what is important, useful, and valued within their school organization. In this way, the school culture will reflect not only the common goals of administrators but of teachers as well. If teacher collaboration is recognized as a valuable practice, the necessary resources will likely be made available to make it a reality.

| Figure 7.1 | Elements of a Positive School Culture |

Another concern is that ELL populations may be marginalized by the school culture along with the very programs that are designed to meet their educational needs. In fact, some ESL teachers have reported that they also feel marginalized and that they wish their students would have access to resources such as classroom aides, suitable textbooks, and supportive technology that are available to other student populations.

At times, a school culture may need to be revitalized in order for teacher collaboration to take place most effectively. This most certainly will not happen overnight. It takes much time, patience, and nurturing to develop the necessary trust, understanding, and acceptance for quality teacher collaboration to occur.

Teacher collaboration takes many forms, and within a week’s time in any school building, teachers will be involved in a number of different collaborative practices. Some of these practices represent the de facto, on-the-fly type. One teacher might see another in the hallway or have a quick chat between regular class sessions. Although a hallway is not the ideal setting for collaborative conversations, informal spaces can play an important role in the overall collaborative process.

Formally planned meetings will require a different type of meeting space. Will gradelevel meetings, structured department meetings, professional development or technology workshops, and faculty meetings that provide whole-group or small-group discussion all be held in the same place?

Schools across the country vary in size, shape, layout, and building capacity. Some school campuses have the capability of accommodating large student populations, which often translates to having the facilities that enable faculty and staff members to meet regularly. Faculty rooms, staff cafeterias, all-purpose rooms, and department offices can all be put to good use for collaboration. Unfortunately, some schools are overcrowded and have difficulty supporting their student populations let alone being able to provide readily available meeting space for teachers.

The following spaces are usually available for casual conversations that take place throughout the school day:

These informal areas limit the types of professional conversations that can take place. One must be careful when discussing individual students or confidential matters in public or shared spaces. In addition, the physical size of the school building may be a deterrent to informal conversations between faculty members. Large urban schools that house several thousand students generally have multiple floors and hallways in which some pairs of teachers would rarely meet.

Areas of school buildings that do not house students are precious commodities. How these faculty-only spaces are used often indicates what is valued by the school culture. One school whose administrators and staff are concerned with health and well-being may have a fitness room occupy an available space while another may have a teachers’ lounge filled with comfortable sofas, a lending library of popular novels, and a seemingly bottomless pot of coffee. Similarly, if members of a particular district value collaboration, mechanisms will be in place for it to occur regularly. One such way to provide access to teacher collaboration is through formal meeting spaces.

At Shaw Avenue School, new building principal Ms. Angela Hudson had a particular vision for a specialized literacy location where teachers would be able to find classroom resources to assist their literacy lesson planning and be able to have regular meetings with the district’s literacy coach. Both her vision and the hard work of several teachers produced the Literacy Suite, a room filled with leveled, guided reading material, big books, reader’s theater scripts, and professional literature. However, the Literacy Suite not only became an excellent place to find classroom resources, it blossomed into a centralized meeting place for teachers to collaborate.

The Literacy Suite is half the size of a regular classroom, and it originally housed the office of the school’s superintendent. In more recent years, it served as two small classrooms for the school’s remedial reading program. Its renovation into a teacher meeting spot was realized through numerous donated items and time spent planning. For its décor, items such as window curtains added visual appeal. Teachers also contributed materials for student learning in the form of class packs of novels, expository text sets, professional books and journals, and portable technology. Other materials for the lending library were purchased with budgeted funds. In addition, school personnel chipped in to buy a state-of-the-art beverage maker that brews individual servings of coffee and tea.

Whether it’s during their prep periods, lunch breaks, or time before and after school, teachers frequent the Literacy Suite to “shop” for new materials, get quick advice from the literacy coach, or grab their favorite hot beverage. It is a place where groups of teachers eat lunch together, share ideas, and help each other plan lessons.

The Cordello Avenue School in Central Islip, New York, has a special place called the Book Room. As Yanick Chery-Frederic showed us around, she explained, “When you peek in, you see neatly organized floor-to-ceiling book shelves all around the perimeter of the room. The shelves contain literacy, content-based, and ESL resources on all grade levels taught in the building. The Cordello Book Room was established in 2001, as a mandate of our Literacy Collaborative Initiative.”

The Book Room is accessible to all teachers and has an organized policy for borrowing books. Specific needs of the ELL community are addressed via a book selection that simultaneously acknowledges language needs as well as the importance of providing culturally rich and diverse literature.

There are numerous volumes of leveled books for implementation of small-group instruction. There is a large selection of shared reading books and recommended read-alouds for beginner ELLs. Grade-appropriate texts of different genres are also available. In addition, a variety of teacher resources that support ELL curricula occupy a section of the Cordello Book Room. Also obtainable are units of study for different writing genres—including poetry, personal narratives, how-to writing, nonfiction, fiction, memoirs, essays, and more. These units invariably consist of components that can be differentiated to specifically target ELL student writing curricula. The resources have been carefully collected, organized, and reviewed over the years by a committee to make sure all subject matter content and essential skills are supported with multiple and varied instructional resources. The Book Room is not just a professional place for teachers to pick up workbooks or browse teacher guidebooks; it is also a meeting place where important professional conversations about students’ needs and best practices to respond to those needs may take place.

Susan Dorkings, the study skills/ESL department chairperson at the William A. Shine Great Neck South High School in New York, describes a unique place for ELLs and teacher collaboration. Over 10 years ago, the administrators of South High School decided to create a Study Center where various academic labs throughout the building were centralized in one location. Over the years, the Center evolved to a program staffed by 11 qualified teachers and teaching assistants. The teachers rotate through a schedule designed to provide support in math, science, social studies, and English each period throughout the day and before and after school. In addition, two reading teachers and two ESL teachers are part of the team. They share the same work space with students, creating an atmosphere where serious academic work takes place. For this reason, collaboration among Center teachers and communication with classroom teachers, guidance counselors, administrators, and other support staff is an ongoing process. This collaboration, both formal and informal, is key to the success of this program.

Many students are assigned to the Study Center program as part of their schedules. Others take advantage of the support provided and drop in for help when needed. During a period, students can receive help in one academic area or in multiple subjects. Study Center teachers, who have access to students’ progress reports and grades, direct students to the teacher who can best address their needs.

Study Center teachers collaborate formally and informally to develop strategies that engage all students in the school—including the ELL population. Although the focus of instruction is directed toward each student’s course work, teachers are aware that many students need to build their basic skills in reading, writing, listening, speaking, and studying. Therefore, the collaboration of academic specialists with reading, ESL, and special education teachers allows for a team approach toward the development of strategies that address those skills. Each member of the department brings his or her expertise, experience, dedication, and enthusiasm to the Center each day. Students respect the knowledge of the teachers and feel welcomed and supported.

Faculty members who do not have the time or the available space to meet with each other during the school day are learning how to collaborate using virtual meeting spaces. Technology is enabling teachers to collaborate from different locations, even from the comfort of their home office or living room sofa. There are Web sites where you can access virtual tools to conduct meetings on the Web; some are available at no cost. Anyone with access to a desktop computer easily can connect to a virtual meeting location. Some Web sites even offer secure meeting sites so that confidentiality is assured. These virtual meeting spaces allow participants to present information, share documents, and collaborate in a way that can be equally as effective as a face-to-face meeting.

A quick search for free Web-based chat software will yield many options for teachers to explore. The “Messenger” feature of numerous Internet service providers also provides chat rooms for group discussions, file transfers, photo sharing, and even audio and video capabilities to enhance the online collaborative experience. Colleagues can identify a convenient time to conduct their meetings from their desktop. Another online tool, Google Docs, allows groups to collaborate and share their work online. Documents such as lesson plans, curriculum maps, and student reports can be uploaded to a secure location on the Internet. Anyone with permission may access the documents from any computer as well as edit and share changes to the documents in real time.

Apart from general apprehension about, or lack of experience with, new technology, there are other difficulties teachers may face when trying to engage in collaborative conversations using Web-based tools. Although most educators have a personal computer in their home, many of these collaborative Web sites require certain computer specifications for them to work effectively. In addition, in spite of being sufficiently computer savvy, some teachers resist scheduling meetings, even virtual ones, outside the school day. They may feel these meetings intrude on their own personal time, while others are obligated to follow local teacher-union guidelines regarding contractual work hours and extracurricular activities. See Table 7.1 for a summary of some of the most prevalent advantages and disadvantages of using Web-based technology for teacher collaboration.

| Table 7.1 | Pros and Cons of Virtual Collaboration |

| Collaboration and Web-Based Technology | |

| Pros | Cons |

|

|

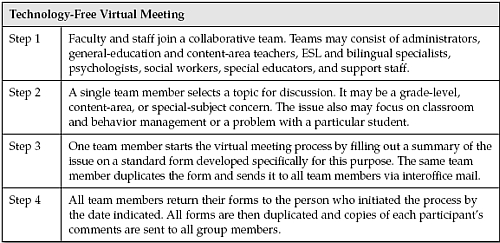

Another type of virtual meeting can be conducted without the benefit of large blocks of time, meeting space, or technology. It can be accomplished by the use of a simple paper form and interoffice mail. Table 7.2 outlines how to establish technology-free, virtual collaborative opportunities.

Virtual meetings of this nature require little time and commitment on the part of group members, yet most participants can contribute to the process within the confines of the school day. It provides opportunities for a variety of staff members to offer their suggestions and advice to those who may have special concerns and can engage faculty members who are only available on a part-time basis. See Figure 7.2, which offers a sample template for preparing for or documenting the outcomes of virtual meetings.

| Table 7.2 | Steps to Create Technology-Free Virtual Meetings |

| Figure 7.2 | Virtual Meeting Form |

Copyright © 2010 by Corwin. All rights reserved. Reprinted from Collaboration and Co-Teaching: Strategies for English Learners, by Andrea Honigsfeld and Maria G. Dove. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin, www.corwin.com. Reproduction authorized only for the local school site or nonprofit organization that has purchased this book.

Whether Web-based or technology free, meetings that do not require a face-to-face presence by their participants can be an essential form of collaboration to benefit ELLs. General-education teachers with little or no experience with the special needs of ELLs can ask for help and receive advice within a short period of time from a variety of practitioners. ESL teachers who are struggling to find solutions for ELLs who have difficulties outside second language learning can seek help from their colleagues specializing in K–5 classroom teaching, content-area subject matters, or special education.

In the past, the responsibility of assisting the classroom teacher or problem solving for ELLs rested solely on the shoulders of the ESL teacher. However, through virtual meetings and other forms of collaborative practice, classroom teachers can be guided by the expertise of different members of the school community, of which the ESL teacher is an essential member. In addition, ESL teachers will be more capable of remedying the situation at hand with the assistance of their general-education peers. Virtual meetings can assist all school community members to move in the direction from a “your kids” to an “our kids” mentality.

If your school is involved in an initiative to “go green,” a paperless version of the virtual meeting can be accomplished in a low-tech fashion by simply using interoffice e-mail protocols. A standard meeting form can be sent electronically to all team members following steps that are similar to the paper version. The member who initiates the meeting writes one e-mail message with the completed form attached and sends it to the multiple team recipients. Team members may return their feedback electronically to all participants, eliminating the need for duplicating feedback messages. This version is only useful for schools in which all collaborative partners have easy, in-school access to a personal computer. Everyone involved should also have an official school e-mail address because some faculty and staff may not want to provide information regarding their personal e-mail accounts. If computer access is difficult, or if the school culture is one in which e-mail is not frequently used, this electronic version of the virtual meeting will be less effective.

The school day begins with most teachers entering the school building, visiting the main office, performing a few clerical duties, offering some brief morning greetings, and proceeding to their separate hallways. From the moment the morning bell sounds, these practitioners remain isolated in their classrooms away from their peers, left alone with the students in their charge to meet the day’s challenges.

Teachers, generally speaking, are accustomed to having their classrooms as their sole domains and take comfort in the modicum of control they hold in their workspace. They set their own class routines, arrange student seating to suit their own lesson ideas, and decide what to teach, where to teach it, and when activities will take place within school policy guidelines. However, when ESL and general-education teachers work together and share the same classroom, there is a different dynamic. Deciding where and how instruction occurs involves careful planning, negotiation, practice, assessment, reflection, and adjustment between those responsible for a co-taught classroom.

Teacher collaboration can have a tremendous influence over the way instruction is delivered for ELLs and a great impact on how these students are regarded. It involves sharing student information, lesson ideas, teaching strategies, and, with certain ESL programs, sharing classroom space. Yet, many factors must be considered when two teachers work so closely together.

Co-teaching requires many teachers to move out of their comfort zones and into unknown territory. Space is not only the final frontier, as a voice from a popular 1960s television series told us, but for some teachers, it is the only frontier. Classroom space is a closely and carefully guarded commodity. Some people, generally speaking, need more control over personal space than others in order to feel sufficiently relaxed and confident to meet the school day’s challenges. Concerns about classroom space and how it is best used can bring about a great deal of anxiety and cause conflict between those who must share it.

Examine the behavior of colleagues when they hear someone is changing their position in the district or retiring, and you will observe many of them vying for the soon-tobe vacated space, particularly if it is a plum spot. With overcrowded classrooms and schools bulging at their seams, no wonder general-education teachers need all the courage they can muster to open their doors and share their classrooms. On the other hand, ESL teachers do not always understand what the fuss is all about. Most of their careers are spent in small, divided classrooms, shared office spaces, all-purpose rooms, borrowed classrooms, hallways, or spare closets next to gymnasiums or music rooms. Most ESL teachers have never had the joy of classroom “ownership,” and so they may not understand a classroom teacher’s concerns over the matter.

ESL programs generally are established on the K–12 level according to ELL student population, assessed needs, available faculty and personnel, funding, and resources. Some ESL teachers have the flexibility to select from a variety of program models to deliver instruction while others are restricted to one particular model. The choice of model may have been determined by a program coordinator, building principal, or an administrator at the district level. Some programs establish separate classroom settings for ESL instruction while others prescribe a shared environment. Let’s take a look at some program models that incorporate collaborative practices to enhance instruction for ELLs.

Every teacher needs his or her own personal space. In a co-teaching situation, classroom space needs to be carefully planned and negotiated. A good place to start is to have a conversation with your co-teaching partner or team in order to answer the following general and specific questions:

When ESL teachers enter a general-education classroom for one class period or part of the school day, it is important that they have a “go to” area as soon as they walk in the door. It may be a table in the back of the room, a small desk set aside for their own use, or a designated wall space with their own materials and supplies and an adjacent chair. Having a specific spot for the ESL co-teacher when she or he arrives will lessen classroom interruptions, keep students who are already engaged in learning on task, and prevent awkward moments that can occur. When the co-teacher’s entrance is smooth, it eliminates the feeling that one is an “intrusion” teacher instead of an “inclusion” teacher.

The benefits of sharing classroom space are endless. It not only benefits students and teachers, but it can also send subtle messages about the school’s learning culture to the community at large. Here is a sample of the possible advantages and ideas brought about by ESL teachers who share classroom space with general-education teachers:

In your mind’s eye, travel back in time to the middle of the twentieth century and enter a classic American schoolroom. What you most likely are picturing is a large teacher’s desk sitting front and center, accompanied by rows of stationary, wooden student desks. The classroom walls are covered with chalkboards and bulletin boards. There is little room for students to move about the classroom if they were allowed to do so. Now in the same way, picture the twenty-first-century’s typical classroom. What do you see? Apart from movable furniture, maybe a bit more space, and a computer tucked in the corner, classroom design has not changed very much (Dunn & Honigsfeld, 2009).

Anxiety may often be the first reaction some ESL teachers feel when they must leave their personal class domains and enter another teacher’s space in order to deliver instruction for ELLs. They wonder how they will be able to conduct lessons when their materials and resources are housed elsewhere. Being organized is essential for ESL teachers to successfully meet the needs of ELLs in general-education classrooms. There are several ways to arrange the necessary resources so that they are readily available. The following steps should be considered when getting materials organized for co-taught lessons:

This will depend on the amount of space available in the general-education classroom and the willingness of the classroom teacher to share his or her space. From our own teaching experiences, there is generally little, if any, classroom space available to share. Classrooms are usually overcrowded with students and further crowded with textbooks, reference materials, classroom libraries, and computer stations. Most ESL teaching material will be kept elsewhere and transported to the general-education classroom.

Try to use nearby spaces creatively to house materials if there is no other option available in the co-taught classroom. An ample-sized hallway might hold a tall cabinet where materials can be kept. In addition, storage closets, hidden nooks under stairways, or extra shelf space in the school library might just do the trick.

There are a variety of ways that materials can be transported to and from the generaleducation classroom. One of the best ways is to have a set of wheels that can move ESL resources from place to place. Teacher carts, commercially available in a variety of shapes, sizes, and styles, can provide more than adequate transport.

The goal of using a cart is to create a mobile ESL classroom. In order to make sure the cart is functional, the following planning and preparation is needed:

When a cart is not available or a school has multiple floors that would make a cart impractical, a large, sturdy bag can be used to carry materials. Totes, canvas carryalls, or even backpacks with various pockets and slots to separate items can be a portable solution for getting materials to and from different classrooms. Some teachers even have converted rolling suitcases into efficient, organized, and easily portable containers for ESL materials.

Most classroom teachers are allowed a limited number of supplies—chart paper, erasers, markers, pencils, etc.—and as the school year comes to a close, those items become in short reserve. Yet, ESL teachers cannot always carry all the needed materials from class to class. It would be most wise for the ESL and general-education teacher to discuss which classroom materials can be used by all and what additional materials are needed. For special projects, the ESL and general-education teacher can pool their resources in order to provide the required materials.

This step is a tall order and one that requires a good deal of practice. When ESL teachers co-teach, they may not have their instructional resources at their fingertips—as they would if they were in their own classroom. When students ask questions that create opportune teaching moments, ESL teachers like to rely on certain materials to enhance their explanations: bilingual dictionaries, calculators, globes, literature, manipulatives, maps, photographs, textbooks, and workbooks.

ESL teachers often need to travel light and cannot depend upon having all the necessary resources handy for teachable moments. However, most classrooms have a computer available for use, and ESL teachers can avail themselves of the Internet, which can be a great virtual substitute for traditional resources.

Becoming technologically savvy is imperative. ESL teachers should practice searching for general Web sites that contain maps, photographs, and other useful information for ELLs. It can be helpful to maintain a list of suitable sites to use in the general-education classroom. As teachers become more adept at surfing the Web, they will be able to retrieve information on the spot without prior planning, allowing them to make the most of teachable moments. We certainly recognize that despite security measures, teachers still need to be wary about the appropriateness of the information retrieved from the Internet “on the spot” and make sure unsuitable websites are not used for instructional practices.

A classroom designed for one instructor might not be adequate for co-teaching situations. Both the ESL and general-education teacher must plan and manage the teaching space in a way that enhances lesson instruction and corresponds with the selected co-teaching model. (See Table 7.3 for a summary of the seven co-teaching models we introduced in Chapter 4 aligned to specific space requirements and recommended suggestions.)

| Table 7.3 | Co-Teaching Models and Organizing Classroom Space |

Let’s revisit our two teachers, Christine and Sara, from the opening vignette. They spent much time planning their co-taught social studies lesson. Together they reviewed the learning standards, explored the grade-level curriculum maps, examined Web sites, and planned a detailed project that included both language and social studies content objectives for their ELLs. Both Christine and Sara need to plan their use of space in a way that will appropriately address their co-taught lesson objectives as well as make both teachers more comfortable in their shared classroom.

Tanner and Lackney (2006), Uline, Tschannen-Moran, and Wolsey (2009), and many others have been investigating the impact of school facilities on student learning. When classroom design is the specific focus, many educational facility planners, architects, and school administrators note the trend of replacing individual student desks to create new opportunities for learning. The following elements are frequently identified features of a well-designed classroom that accommodates a range of varied learning needs:

Building on social cognitive theorists, Van Note Chism (2006) suggests that “environments that provide experience, stimulate the senses, encourage the exchange of information, and offer opportunities for rehearsal, feedback, application, and transfer are most likely to support learning” (p. 2.4). When two or more teachers share the responsibility for creating such a stimulating learning space for their students, they have the opportunity to do the following:

In addition, learning-styles researchers and practitioners also addressed the importance of classroom design to better respond to varied learning needs of students. Irvine and York (1995) state that “all students are capable of learning, provided the learning environment attends to a variety of learning styles” (p. 494). Dunn and Honigsfeld (2009) suggest that teachers create separate classroom sections in which students may work

Tomlinson (1999) also recommends that flexible grouping arrangements allow teachers to move away from creating tracks (separating students into low- and high-achievement groups) within the class, but rather group students in different ways at different times. In such a differentiated classroom, ELLs are sometimes grouped together for instruction, whereas at other times they are placed with their more proficient English-speaking classmates. As Tomlinson proposes, teachers should consider differentiating for content, process, and product based on their students’ readiness level, interest, and learning profile.

When you are deciding on grouping configurations, use the following guiding questions:

To be successful in redesigning the traditional, transmission type classroom model—in which one teacher spends much of his or her instructional time in front of the entire class—it is important to establish class routines and rules of behavior that both teachers in the co-taught classroom adhere to and enforce. These rules and behavior management strategies can change from classroom to classroom and between different co-teaching teams. There are some basic guidelines that should be followed when establishing classroom management practices.

Here are some tips for jointly establishing an effective learning atmosphere:

The building administrator’s role is to create physical and virtual spaces that support the collaborative team’s planning and instruction for ELLs. This can be accomplished in a variety of ways.

| 1. | Carefully develop ELL placement policies and consider their implications. Cluster ELLs based on your local population and demographics.

|

| 2. | Assign ELLs to general-education classroom teachers at the elementary level and content teachers at the secondary level who demonstrate the highest levels of knowledge and skills regarding second language acquisition, cultural responsiveness, ESL methodologies, and who volunteer to be selected for such a task (thus also demonstrating the necessary professional dispositions and positive attitudes toward linguistically and culturally diverse student populations). |

| 3. | Assign teachers to work together who complement each other’s knowledge base, skills, competencies, and who are willing to engage in collaborative practices. |

Most of all, create a school culture that respects both an inclusive and safe learning space for all ELLs and teacher collaboration spaces that inspire and support teachers in their efforts to work together.

Creating and sustaining real and virtual spaces for teachers to collaborate responds not only to the essential Maslowian (1970) need for “shelter” but also for the need for “safety and security.” Despite the critical shortage of available space in many schools, ESL and general-education teachers will only be able to collaborate and co-teach successfully if real and virtual space is provided for planning, delivering, and assessing effective instruction and for being engaged in job-embedded, continued professional development.

| 1. | Sarah Elmasry (2007) claims that “learning environments are directly correlated with the pedagogical practices taking place within them; patterns of space are driven by patterns of events” (p. 28). What are the patterns of spaces and events in your own professional life? | |

| a. | Reflect on the patterns of instructional and noninstructional events that keep happening in your classroom or school. What teaching model is adapted? What are the most common teaching-learning activities that recur? | |

| b. | Review the patterns of space in your classroom or school building: In what way do the patterns of space impact upon the patterns of events? | |

| 2. | Revisit Figure 7.1 depicting the elements of a positive school culture. With your colleagues, discuss which of the elements presented in this figure have appeared to be most essential to support the education of ELLs. | |

| 3. | What are the attributes of a collaborative school environment? Consider both what you have read in this chapter and your own experiences. Generate a list of key characteristics you would like to see further developed in your school. | |

| 4. | How does the teaching-learning environment help teachers develop collaborative practices? In what ways may it hinder such practices? | |

| 5. | Sketch a floor plan of an ideal classroom where co-teaching could take place most effectively. Consider the need for changing the floor plan to accommodate various co-teaching models. Draw in as many details as possible. Share and discuss your drawing with your co-teacher or other co-teaching teams for additional input. | |

Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development

www.ascd.org

Classroom Design

http://classroom.4teachers.org

Classroom Management

www.thecornerstoneforteachers.com

Differentiated Instruction

www.caroltomlinson.com

Learning-Styles-Based Instruction

www.learningstyles.net

Learning Styles Classrooms

www.flipthisclassroom.com

Multiple Intelligences

www.howardgardner.com

School Improvement Research Series at Education Northwest

http://educationnorthwest.org/resource/825