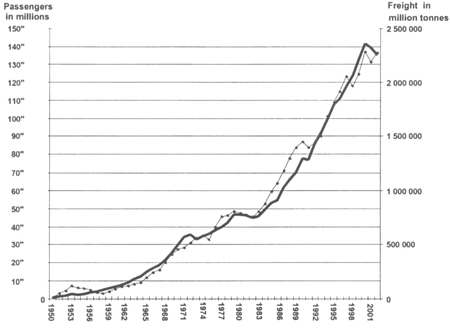

Figure 12.1 Passenger and freight movements at German airports

Source: Arbeitsgemeinschaft Deutscher Verkehrsflughäfen

Hans-Martin Niemeier

The two issues of capacity utilization and expansion, and price regulation, and the links between them, are explored in this paper. In Germany, there is a perceived problem of the adequacy of airport capacity to meet demand. Excess demand can be met by building more capacity, but capacity can also be rationed more efficiently than it is at present, by price and other means. The system of price regulation that is implemented will influence the price structure, and hence how urgent are investments in extra capacity.

Since September 11th 2001 passenger volumes decreased significantly by 11.6 per cent, freight by 9.0 per cent, and commercial movements by 8.2 per cent at German Airports (ADV). Given that the current crisis in aviation, which started with the worldwide slump at the end of 2000, will probably last longer than the Gulf crisis and might even lead to structural changes (Costa et al, 2002), capacity extension of airports seem to be an odd theme. However, even the most pessimistic scenarios assume that after a period of three or four years of gloom growth rates of the aviation industry will be back at the high levels of the last decades. Thus, the topic of expanding capacity or the inadequacy of airport infrastructure, as the aviation industry has called it, will soon be back on top of economic and political management of the industry.

In the meantime it might be useful to step back and ask how serious the capacity problem is, whether there is really a "capacity crisis", how capacity problems have been so far dealt with, and whether or not there are options for improved solutions. In this chapter I shall first try to assess the capacity problem at German airports by looking at the situation before 9/11 and the forecast situation for the year 2010. It will become clear that the airport system as a whole is in a situation of persistent overcapacity, but at the same time, there exist partial capacity shortages because the price mechanism does not work effectively. Thereafter, the shortcomings of the price mechanism and the politics of airport extension will be analysed in sections 3 and 4. I shall argue that the current practice lacks economic rationality and leads to an inefficient allocation of resources (section 5). Therefore, in section 6, it seems necessary to look critically at the rules of the game, namely the current cost based regulation of airports. I shall argue that this type of regulation is not appropriate for overcoming the current misallocation of resources and should be reformed. Several options are discussed briefly in section 7 and price cap regulation is favoured (section 8). While price cap regulation has the advantages of leading towards an cost efficient infrastructure and to a better utilization of existing capacity in the short run, the regulation is said to have certain dynamic drawbacks in the long run, namely poor incentives for investment. This charge will be analysed in section 9. Finally, before summing up I shall argue that price cap regulation should be part of a larger reform of setting incentives for an efficient static and dynamic allocation of airport resources.

Figure 12.1 Passenger and freight movements at German airports

Source: Arbeitsgemeinschaft Deutscher Verkehrsflughäfen

Germany has 18 international airports and over 20 regional airports with scheduled or charter traffic. In 1990, the international airports served 80 million passengers and in 2000 143 million (+79.7 per cent). Freight volumes rose from 1.5 million tonnes to 2.3 million tonnes (+53.8 per cent). Commercial movements increased by 54 per cent from 1.2 million to 1.85 million in this period.

Instead of giving an overall picture of capacity problems I shall look at four representative examples. I shall start with Frankfurt airport and then look at the airports of Stuttgart, Hannover and Hamburg.

Frankfurt airport, Lufthansa's original hub, is the largest airport of Germany with 48 million passenger movements, 1.476.374 tonnes of freight and 448.499 commercial movements. It serves twice as many passengers as Lufthansa's secondary hub at Munich and has a market share of 35 per cent of passengers and 67 per cent of air freight in the German airport market. At a first glance, Figure 12.2 shows that the slots for arrival and departures are fully utilized (crosses) for almost all hours of the day.

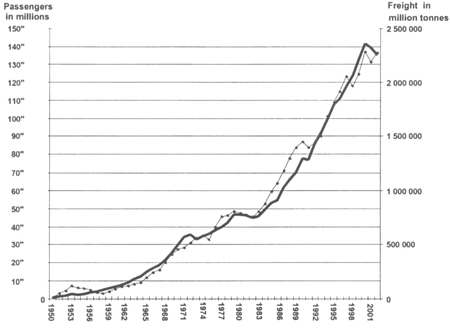

Figure 12.2 Slot coordination at Frankfurt Airport (summer 2001)

Source: Deutsche Flug Sicherung

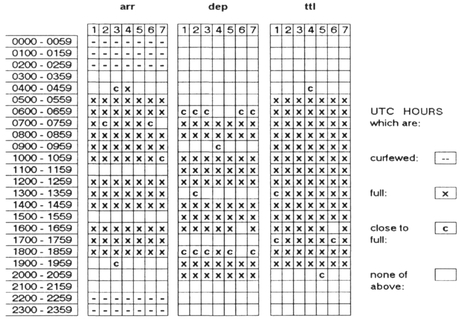

At Frankfurt Airport the demand for slots is greater than the supply. It is obviously a congested airport. Taking a closer look, however we see that certain hours are only close to full (c) and even that still some slots are still available at certain less attractive times. The picture of a capacity crisis does change dramatically by looking at other German airports. At Stuttgart airport, with 7.6 million passengers the sixth largest German airport, no crosses appear (see Figure 12.3). However, the airport obviously has a peak problem in the morning and evening times of weekdays. In these hours the capacity is close to full and the hidden demand is probably greater than the capacity.

Such peak problems also occurred at Hamburg airport in the 1990s. A new apron has increased capacity by 25 per cent, now allowing 51 movements per hour instead of 42 so that, at Hamburg airport, the peak problem has almost vanished. At Hannover airport the situation looks even better. Only from 8 to 9 a.m. are the slots for arrival nearly fully utilized so that even at peak times the demand for slots does not reach the capacity limit. This situation is typical for all German airports with the exception of the heavily congested Düsseldorf airport, which is not allowed to use its second runway for environmental reasons. None of the other 13 airports has yet reached its capacity limit and this is even more the case for the small regional airports.

Figure 12.3 Slot coordination at Stuttgart airport (summer 2001)

Source: Deutsche Flug Sicherung

The situation in 2001, just before 9/11, can be summarized as follows. The main hub of German airports, Frankfurt, suffers from excess demand, but out of secondary hubs (with the exception of the environmental constrained Düsseldorf) only a few airports such as Stuttgart and Hamburg are facing peak problems, while all the other airports have idle capacity.

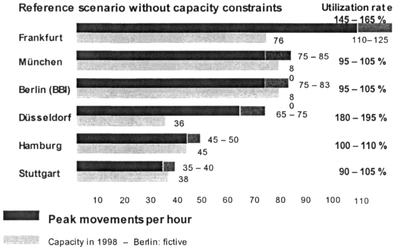

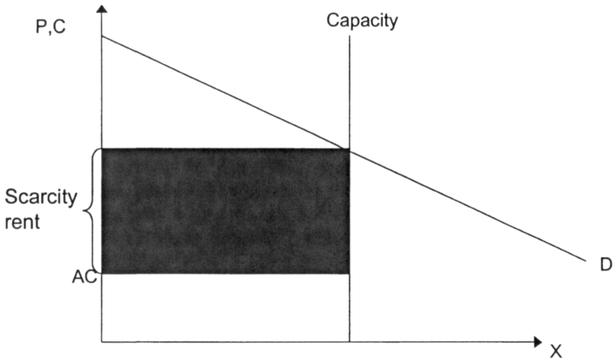

Will this situation change in the future? According to the latest forecast of the DLR, capacity problems will become more severe (Urbatzka et al, 1999).1 The DLR has developed three scenarios. The first scenario assumes that no capacity constraints hinder the development of aviation. Passenger movements at German airports should rise from 113 million passengers in 1996 to 181 million passengers in 2010. The airlines are forecast to use relatively small aircraft so that the supply of seats per flight stays at the level of 1996. The rise of passenger demand will lead to an increase of total movements from 1,980,000 to 2,952,000 with commercial movements up from 1,519,000 to 2,383,000. Capacity problems will become acute at certain airports. Frankfurt and Düsseldorf will be heavily congested. At peak times, demand increases of up to 165 per cent of capacity at Frankfurt airport, and 195 per cent of capacity at Dusseldorf airport are forecast. For Berlin, Stuttgart, Munich and Hamburg peak problems are also forecast.

Figure 12.4 Peak demand and supply in the unconstrained scenario for the year 2010

Source: DLR

In order to balance this excess demand the DLR develops two further scenarios. The first one is supply driven and projects increases in aircraft size and load factors without altering the airport choice of the traveller. This leads to a significant reduction of total movements to 2,759,000. The margin of excess demand decreases by 35 per cent at Frankfurt airport and by 45 per cent at Diisseldorf airport. However, this reduction still does not balance demand and supply. Therefore, the DLR develops a third so called "market based scenario" assuming an increased capacity at the six airports with capacity problems in a range between 5 and 20 percent,2 a partial shift of leisure traffic from Frankfurt and Diisseldorf to smaller airports, and a shift in the modal split due to new high-speed trains and a closer cooperation of Lufthansa and German railways. Total commercial movements stay at the level of the second scenario, but movements at Frankfurt and Düsseldorf are again slightly reduced thereby balancing supply and demand. Munich, Berlin, Hamburg and Stuttgart are all forecast to have peak problems in 2010 (Figure 12.5).

Figure 12.5 Peak demand and supply In market based scenario for the year 2010

Source: DLR

According to this forecast, German airports face capacity problems, but speaking of an overall capacity crisis seems to be misleading. There are likely to be three groups of airports. The first group of airports are small international airports such as Bremen, Hannover or Saarbrücken and regional airports such as Kiel, Lübeck and Hahn. These airports are by far the majority. They provide enough idle capacity with slots still having the character of a public good such that there is no rivalry for landing and departures. The second group consists of airports with high utilization rates and excess demand at peak times such as Hamburg and Stuttgart. Slots cease to be a public good and become an ordinary private good. Thirdly, we have the group of airports facing excess demand for much of the day. Only at Frankfurt and Düsseldorf are slots permanently scarce.

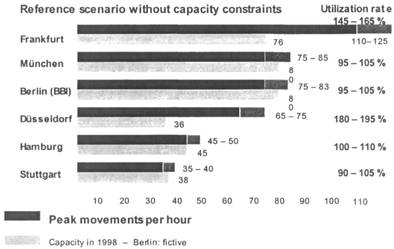

Comparing the market for airport investment and pricing with a well functioning market, it becomes obvious that something must be fundamentally wrong with the industry. It seems that idle capacity and excess demand prevail at the same time for relatively long periods with inefficient rationing and slow reactions of prices and new capacity. The short and long term reaction of an industry to a rising demand was first worked out by Marshall (1890), refined by Viner (1931), and then made its way into standard micro economics and transportation economics. According to Button and Stough (2000, p. 191) the "generally accepted position" assumes3 that the airport industry has a modified L-shaped average cost curve with initially decreasing cost and economies of scale and density flattening out after a certain level (compare Figure 12.6).

The market clears initially at price of p1 with output at x1 thereby inducing the airport to increase supply along the short run marginal cost curve to the level of x2. Markets clear at a price of p2. Again the price at level p2 induces airports to expand capacity and to increase supply along the short run marginal cost curve leading to another round of price and output expansion. Step by step the airport industry adds capacity until the long-term equilibrium is reached, where supply and demand balances without inducing an expansion. In this point welfare is maximized as the output is produced with minimal average costs.

Figure 12.6 Expansion of the airport industry

Source: Button and Stough (2000)

Why is the airport industry not operating in such an ideal way? I would argue initially that the price mechanism is not working very efficiently and later that the regulatory framework sets incentives such that this inefficiency is encouraged (section 6). In the airport industry, two mechanisms are used to allocate resources, namely airport charges and slot allocation by the IATA procedure guide. Airport charges for landing and take off are weight based, the passenger charge is related to the number of passengers, parking charges are weight and sometimes time based. These charges were quite successful in financing infrastructure in a regulated environment. However, they are not suited for a liberalized aviation market as they are not efficient, in an economic sense. Various studies have shown that the current charges have the following disadvantages. At an uncongested airport, charges have only a relatively weak relation to costs and do not set incentives to airlines for a cost minimizing use of the take off and landing system. They are not strictly based on first best marginal pricing or second best pricing such as Ramsey pricing (Morrison, 1982; Doganis, 1992).4 This means that at most German airports with idle capacity an inefficient pricing regime is practised. However, these inefficiencies become more important at those German airports with peak problems and with congestion. At these airports, airport charges based on some average cost concept do not incorporate the external effects of congestion or reflect the scarcity of slots. No effective peak pricing and no congestion pricing has been practised at German airports with scarce capacities in the past decade (Niemeier, 2002a).

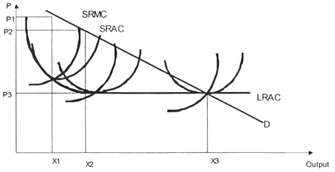

The IATA rules of slot allocation stem from the period of a regulated aviation market. They give commercial traffic priority over general air traffic and give grandfather rights to slot owners. In a regulated environment these rules make some sense as they give planning security to scheduled traffic and reduce the congestion. However, they are not appropriate for the efficiency demands of a liberalized market, as economists have pointed out in the last 30 years (e.g. Levine, 1969; Fridström et al., 2002). The conclusion of economists is almost unanimous; the current slot procedures result in an inefficient allocation of resources as slots are not allocated to those who value them the most. The IATA rules distort competition among airlines by erecting barriers to entry and the rents from slots do not flow to the airports that could expand capacity and eliminate the slot scarcity. These inefficiencies lead to the situation at congested airports that charges are set at some measure of average cost so that the airports can live quite well and the airlines receive all the scarcity rent as the airline eliminates the excess demand by changing their passengers market clearing prices into/out of the constrained airport (Figure 12.7).

This situation seems to be quite stable.5 At least for the last couple of decades the coalition of rent seeking airlines and rent providing airports has worked smoothly. German airports have shown no or relatively little initiative in installing a workably efficient price mechanism. They have not used the degrees of freedom the legal system offers in utilizing differential charges. Only the partial privatized Düsseldorf airport has commissioned a study (Ewers et al, 2001) to reform the price mechanism, but it has so far not implemented an efficient pricing strategy.

Figure 12.7 Slot scarcity

While German airports have not adopted an efficient pricing strategy they have focused their strategy on the expansion of capacity, which involves almost natural politics because of the negative environmental impact. German airports have developed a strategy based on a predict and provide philosophy and on a logic of jobs versus the environment. A complete analysis of the politics of airport expansion lays outside the scope of this paper. I shall confine myself to two representative examples. The first is the expansion of the apron at Hamburg airport. The second example is the mediation process of Frankfurt airport for a new take-off and landing system. It shows the logic of jobs versus the environment.

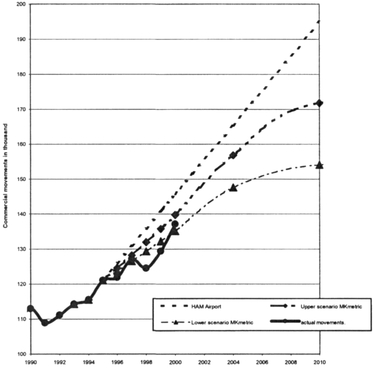

In the 1990s the state-owned Hamburg airport still had enough runway and terminal capacity, but growth was seen to be restricted by limited space for aircraft parking positions. In addition, the airport was forced by a court ruling to seek permission for any expansion through a process of public inquiry. Hamburg airport based its application for its development plan in 1996 on a forecast of passenger demand and movements (Flughafen Hamburg GmbH, 1996). At about the same time the Ministry of Economic Affairs of Hamburg had also commissioned a forecast by MKmetric (Mandel, 1997). Comparing each forecast with the other and with the actual development up to the year before the current crisis provides an interesting evaluation, as it shows the intentions of the airport management. Both forecasts expect similarly strong growth of passenger demand in a range between 13 (MKmetric) to 13.85 million passengers (Hamburg airport) in 2010. The forecasts largely diverge in the prognosis of commercial movements. Hamburg airport forecasts 195,000 commercial movements in 2010 while MKmetric forecasts 155,000 and 172,000 at maximum (see Figure 12.8). These differences can be largely explained by the fact that Hamburg airport extrapolates a trend of commercial movements independently from the passenger forecasts while MKmetric derives the number of commercial movements from passenger demand. Given the supply of aircraft orders and the tendency towards rising load factors at the point of forecasting in 1995/6, MKmetric forecasts a relationship of 77 to 86 passengers per commercial movement in the year 2010 while Hamburg airport's method resulted in a marginal rise from 68 to 71 passengers per commercial movement. The latter could only happen if the airlines reverse their former decisions and order smaller aircraft and/or reverse their policy of increasing load factors. Neither explanation seem to be very realistic in a liberalized aviation market with a strong growth of leisure traffic.6 The high numbers of movements seem to reflect an inconsistency between the number of movements and the passengers. To be more precise, at Hamburg airport the commercial movements follow the forecasts of MKmetric and are, in 2000, about five to ten thousand commercial movements below the forecast of the airport with a widening gap up to 40,000 commercial movements in 2010.

The airport management insisted on the validity of its forecast and based the airport expansion on this over-optimistic forecast. It seemed to follow the logic of predicting and demanding as much growth as possible with the hope that politics will follow the expertise of the airport and provide permission for the expansion.

This strategy involves major risks. Firstly, it leads to a tendency that too much capacity is provided too fast. It leads to relatively capital intensive production with relatively high fixed costs and low marginal costs. Yet, since airports must break even, the financing charge leads to a high average charge per aircraft and passengers. Secondly, the expansion of peak capacity is generally paid by all users, resulting in too low charges for the peak times served by the incumbent national carrier with grandfather rights and too high charges for off-peak times generally used by charter and new entrants. This tendency might result in a high yield market with lower passenger volumes and less attractive connections.

Finally, the strategy increases the risk of losing the acceptance of the airport in the adjacent neighbourhoods as the negative environmental impact is inversely related to movements. In the case of inner city airport Hamburg, the noise emissions, based on the movement forecast, were rising dramatically up to a level which would be sufficient for 20 to 23 million passenger movements. The policy in Hamburg reacted by accepting the forecast of MKmetric and implementing a noise budget, capping the noise levels at the level of 1997 (Niemeier, 2000). At other German airports such a rational outcome might not be reached and the expansion of airports might be blockaded.

In the past, the expansion of Frankfurt airport produced severe opposition leading to "one of the biggest and longest lasting political controversies of the Federal Republic of Germany" (Hujer and Kokot, 2001). The airport's plan to build a new runway will therefore not to be easy to achieve. Before going through the official public planning process, a mediation process should decide on the question of whether or not Frankfurt airport should be extended.

Figure 12.8 Comparison of forecasts for Hamburg airport

Mediation started in summer 1998 and the report was issued at the beginning of 2000. Several studies about the economic, ecological and social consequences were conducted on behalf of the three mediators and the supporting mediation group. AH studies were thoroughly discussed in working groups and the scientific advice was cross-checked by other scientists. Five scenarios were defined, ranging from a reduction of movement over the current status to a full-scale expansion. Crucial for the decision was the result of the Input-Output study by Hujer and Kokot (Bulwien et al, 1999). The study came to the conclusion that while currently 142,000 jobs are directly or indirectly dependentd on the airport in the federal state of Hessen, the full-scale expansion would create an additional 57,000 jobs.

The concept of a mediation process is, in principle, a useful instrument. The transparency, rationality and the democratic legitimization of such a major infrastructure project can be increased compared with the ordinary planning process because, at a very early stage, all parties can participate. This presupposes a certain trust in the independence and rationality of the whole process. However, not all parties have such trust as most of the citizens refused to participate. No doubt, excellent studies with new insights were conducted. However, the logic of the mediation process is totally misleading. The mediation report discussed in detail the option not to extend the airport, but "after valuing all aspects" (Mediationsgruppe Flughafen Frankfurt, 2000, p. 178, my translation) recommended the full scale expansion. The mediation group valued the economic impact for Hessen and the Federal Republic of Germany to be of such a magnitude that the expansion became a necessity. However, this is not a rational economic decision because nothing is said as to how all the "benefits" of thousands of new jobs7 are valued against the internal and external cost of the project; in effect a comprehensive social benefit-cost assessment was not carried out. There might be other investment projects with a higher return. Investment decisions are principally a question of the benefits and costs and not a question of direct or indirectly created jobs. Not even the internal costs are mentioned in the mediation report. Given the environmental externalities the political question of whether or not to undertake the expansion of Frankfurt airport should be better rationally decided by an appropriate benefit-cost analysis. The strategy of Frankfurt airport is typical for German and even for European airports, as the Airports Council International recommends the use of such economic impact studies. Investment decisions become then a question of how many jobs can be created by more or less precise input-output analysis so that the public accepts that the people must suffer the negative effects on the environment (Niemeier, 2001).

To avoid any misunderstandings, the argument is not so much about the expansion or otherwise of Frankfurt, Hamburg or any other airport. Expansion may indeed be warranted on economic grounds - however this has not yet been established.

The analysis of the previous three sections leads to the following four conclusions.

The German system of airports shows all the signs of an inefficient allocation of resources and it is just these phenomena which regulatory economics expects from a system of low-powered cost-based regulation. The loosely defined German system seems to be a rate-of-return regulation as it allows charges to be raised with increasing costs allowing for an normal rate-of-return on capital (Niemeier, 2002).

Of course, there might be also other factors such as public ownership8 which contribute to the misallocation of resources, but as the regulatory framework sets the incentives and defines the rules of the game, the cost-based type of regulation plays at least a major role. The more airports tend to become profit-seeking companies the more important these factors will become.

The economic regulation of German airports stems from the times of a regulated aviation market. Unlike the UK, Germany did not change the airport regulations with the liberalization of the aviation market, and even with the beginning of the process of privatization of airports the old system of cost-related regulation of airport charges remained unchanged, with the two exceptions of Hamburg and Frankfurt (see section B). Germany did not even separate the functions of ownership and regulation so that very often they are done within the same ministry of a federal state.

Regulatory economics has developed several methods to increase the efficiency of a system (for an overview cf. Kunz, 2000). I shall confine myself to three concepts that are currently debated by airport regulators and analyse whether these concepts are appropriate for the present situation of the German airport system with its specific institution. In other words, I do not intend to argue in general that the two other options are inferior. The first option is to give up ex-ante regulation and rely on general competition law. It is an option recommended by David Gillen for Canada (Gillen et al, 2001) and David Starkie for the UK (Starkie, 2001). Monitoring, the second option, is the new regulatory system for Australian airports, which supersedes the former price cap regulation (Productivity Commission, 2002). Thirdly, I will discuss the merits of the price cap regulation (see section 8), which I find appropriate for German airports.

Gillen and Starkie argue in short that the airport industry has lost the character of a natural monopoly. The abuse of monopoly power is limited by competition among airports and from other transport modes. Furthermore, the complementarity of revenue from competitive non-aviation and monopolistic aviation business provides an incentive for airports not to charge monopoly prices. The profit-seeking motive will lead even the monopolist to differentiate prices, introducing peak and congestion pricing. As all types of regulation are far from perfect and might result in distortions, the balance shifts towards liberalization and giving up ex-ante regulation. In case airports abuse monopoly power position, the competition regulator can step in.

In the past, airports were depicted as almost natural examples of natural monopoly.9 It is one of the merits of Starkie to have questioned this belief as early as the mid 1980s (Starkie and Thompson, 1985). The empirical support is not conclusive because only a few studies have been carried out. However, research seems to indicate that average costs decline up to a level of 150,000 movements and 12.5 million passengers, stay constant and finally increase as hubs experience diseconomies of scale, due to congestion and environmental constraints (Pels, 2000, Productivity Commission, 2002). There is an agreement about the sunk cost character of airports.

However, the crucial question of up to what level the range of economies of scale and scope prevails relative to demand for a particular airport is hard to answer as the slope of the average cost curve and the borders of the local market are not known. As a first rough guess it seems that Frankfurt and Munich are definitely beyond that range. Düsseldorf might have no cost advantage over Cologne. All secondary hubs such as Hamburg, Stuttgart, Berlin and small airports like Bremen, Dresden, Hannover and Leipzig seem to have a natural monopoly in their origin destination traffic.10 This strong market position is enhanced by legal barriers to entry so that even the hubs face no strong competition in the origin-destination market and only some competition in the transfer market. Perhaps with the exception of the Rhine area around Cologne and Düsseldorf the competitive pressures will be rather low. This at least the case in the North German market, where Hamburg faces an inelastic demand, and doubling the level of airport charges would decrease passenger demand by only 10 per cent Mandel (1997).

Given the mild pressures of competition it is doubtful if airports will be prevented from abusing their monopoly power in Germany. However, the complementarity of the different airport services might be an effective counter force. The complementary nature of non-aviation and aviation services is evident. The question is how strong this relation is.11 I believe that it might be rather less powerful, as a first reaction of an airport management facing the complementarity would be to differentiate airport charges in order to increase traffic and thereby non-aviation revenue. This has not happened at German airports. Giving up ex-ante regulation for Germany might not change much. It may just stabilize a system with monopolistic slack and an inefficient price structure unsuited to deal efficiently with the capacity problems. Also, this inefficient system would have no reason to fear the power of German ex-post regulation. The ruling of the court in the case between Düsseldorf Airport and the airline Hapag-Lloyd is in this respect very instructive. Hapag-Lloyd, as with other airlines, refused to pay an 7.5 per cent increase in charges in April 2000. The court compared the charges of Düsseldorf with other German airports. As the charges were about the same level the court ruled that Düsseldorf was not abusing its monopoly power. The lower charges of price capped Hamburg airport were explicitly treated as an exception (Landgericht Düsseldorf, 2001). The German competition law, at least as practised by the courts, is quite ineffective in setting incentives for efficiency or even preventing the abuse of monopoly power.

Price monitoring is another option. On 13 May 2002, the Australian transport minister decided to abolish price cap regulation and to adopt a more light-handed regulation, namely price monitoring of the main airports for a period of five years with an independent review and the right to reverse powers of price control in case of abusive pricing. The decision is based on a study of the Productivity Commission, which analysed the two options of an improved price cap regulation and a monitoring system. The Commission recommended the latter one (Productivity Commission, 2002) and the minister agreed because monitoring should give "greater scope for airports to price, invest and operate efficiently (Commonwealth Treasurer, 2002, p. 3). In respect to capacity problems, the monitoring system explicitly encourages efficient price systems with price discrimination, peak and congestion pricing.

Monitoring differs from abolishing ex-ante regulation insofar as the behaviour of airports is closely followed. It claims to be more light handed and to avoid regulatory mistakes, but ftom my point of view these claims are doubtful. Price cap regulation gives the airport a price ceiling under which the airport can set freely the relative prices, thereby giving incentives to adopt efficient price structures. The Australian price monitoring system simply sets a range of price ceiling by the qualitative aim of preventing the abuse of market power. Furthermore, it encourages price differentiation by defining it as a review principle. Thus, the differences might be not as great as they appear at first sight.12

To be effective, monitoring needs a credible threat (Kunz, 1999). This has not been the case in New Zealand, as the Productivity Commission points out. Given the expertise gained in five years' experience of price capping and the strong institutional backing of the Productivity Commission, the threat against monopoly abuse and the incentives for efficient pricing may be sufficient in Australia. However, this institutional setting is not present in Germany, which even lacks the institution of an independent regulator. Therefore, monitoring might create a situation similar to New Zealand, where agreements between the airport and its users have led to long lasting litigation, and in the case of Auckland Airport, excessively high prices, such that the Commerce Commission of New Zealand recommended ex-ante regulation (New Zealand Commerce Commission, 2002). Such litigation is a sign that the transaction costs due to opportunist behavior are substantial and a severe problem of the relationship between airports and airlines. The court case between Düsseldorf airports and Hapag Lloyd might be just the beginning of long lasting court actions. Ex-ante regulation by price cap has the advantage of reducing transactions costs as it brings all parties involved together in an orderly described discourse.

The most serious problem13 of German airports is the inefficient distribution of traffic due to a malfunctioning price system leading to the inability of rational investment decision making and to irrational planning processes of airport expansions. In addition, the lack of an independent regulator increases the potential for increasing transaction costs, as the Düsseldorf court case shows.

I would argue that in this specific situation price cap regulation copying the Hamburg model is the best way to improve the current situation of German airports (Niemeier, 2002). This process is gaining momentum as Frankfurt airport has also adopted a kind of fee cap. The price cap regulation of Hamburg airport has been effective from May 2001. It is intended to regulate only the bottleneck facilities. Thus, the price cap is based on a dual till principle, leaving the non-aviation business unregulated. The X is to be determined by the projected growth of productivity without rate of return considerations. Quality of services is being monitored taking into consideration the different quality levels airlines demand. Users are informed through improved consultations. Although the implementation has some shortcomings, for example, not covering the fee for central infrastructure for ground handling, or the asymmetry of the sliding scale factor in case of a downturn in traffic, the model (see below) could easily be developed to be an effective model for regulation of German airports. Essential for such a reform is the establishment of an independent regulator for the industry on the federal level (Niemeier, 2002; Wolf, 1997). The pro and cons of such an approach are as follows.

The cons of such a reform are mainly related to the question of how in practice price cap regulation works. Price cap regulation was intended by Littlechild as a pragmatic approach for a workable regulation of a monopolistic bottleneck without the negative incentives of cost based regulation. In the following discussions, price cap regulation lost some of his theoretical elegance and merits (Bös, 1991). In the static setting, incentives for cost reduction are lessened if the regulator bases his decisions on X on the cost of the regulated firm or on its rate of return. The Australian Productivity Commission has taken up this well known fact and argued that price caps "converge towards cost-based regulation ... with associated high levels of regulatory involvement and risks of regulatory error..." (Productivity Commission, 2002, p. 308). However, from my point of view this argument is not conclusive as the regulator tries to estimate future productivity gains by avoiding gold plating. This intention is limited by the fact that the regulator does not want to set the X below the cost of the firm thereby risking bankruptcy, and also the limited knowledge of the regulator on the cost and demand function of the airport. However, the lag or price cap sets incentives to reveal not all, but at least some of the potential productivity gains.14 Furthermore, benchmarking although far from perfect might be useful to prevent the regulator from underestimating the cost potential in a large degree. "The worse he is informed about costs or demand, the lower the X he must choose", writes Bös (2001, p. 18). However, the opposite can also be true.

One should not expect more from the pragmatic price cap method than it promises, namely fairly good regulation. Bös concludes his theoretical analysis on different regulatory methods that price cap regulation "implies a satisfactory compromise between information requirements for the regulator and negative incentives for the public" (Bös, 2001, p. 6). How well or badly price cap regulation performs in the airport sector has so far been not studied, but the results from other industries at least indicate that incentive regulation reduces prices and costs and performs better than traditional cost-based regulation (Ai and Sappington, 2001, Giulietti and Waddams Price, 2000).

The cons of price cap regulation must be taken seriously: however, they focus on the question how much of a possible productivity gain can be passed to the airlines and the final consumer by price cap regulation. They do not directly15 effect the first necessary object of reform, namely to establish an efficient price structure without high transaction costs in order to use the given capacity more effectively and to have the right price signals for investment. In other words, price cap regulation might not create such good incentives for productive efficiency as some have hoped, but it creates good incentives for Ramsey prices (Bradley and Price, 1988) and peak pricing (Brunekraft, 1998). Therefore, I think it is worthwhile to risk price cap regulation in Germany.

It would be naive to expect that excess demand will vanish forever once prices are established, reflecting the relative scarcity of airport infrastructure. Sooner or later investment in airport infrastructure will be necessary. This raises the question of whether price cap regulation provides sufficient incentives for investment.

Investment in new terminals or in a new runway are long term projects with sunk costs while price caps have a shorter period, usually of five years. In the first stage the regulator sets the price cap, then the airport makes its investment decision and in the final stage the regulator reviews the previous price cap. Obviously, the airport might be subject to opportunistic behaviour of the regulator as it might reduce prices below long run average costs so that the return on investment becomes too low. The regulation might cause underinvestment and the investment decision depends on the credibility of regulation to allow for a fair return on investment (Vickers and Yarrow, 1988).

Helm and Thompson (1991) found that "there are some grounds for believing that privatized utility regulation - as practised in the UK - may result in underinvestment on the part of firms with high sunk cost infrastructure" (Helm and Thompson 1991, p. 238). They named BAA as an example for possible underinvestment. They acknowledged that the empirical question is open and I may add that it still is - both in general for public utilities16 and, in particular, for the UK airports.

The CAA faces the particular problem of regulating Heathrow airport along with Manchester and the other BAA London airports. Heathrow airport faces heavy excess demand. The building of Terminal 5 has been discussed for years. The CAA is confined by law to the economic regulation in the narrow sense, leaving the external benefits and costs of such an investment to be decided in a public planning process. The statutory objectives of the CAA are among others "to promote the efficient, economic and profitable operation of such airports ... and to encourage investment in new facilities to satisfy anticipated demands" (CAA, 2001, p. ix). The investment is characterized by large sunk costs for fixed 'lumpy' capital with relatively low operating costs. The historic accounting values are below the opportunity costs given the land valuations of such an attractive site in west London. In order to address this problem the CAA has evaluated several options for setting the price cap (CAA, 2001).

Firstly, the CAA finds the current standard model with average accounting costs on a single till basis inappropriate as it would lead to the greatest divergence of prices from the market clearing level. Furthermore, it argues that regulation should focus on monopolistic bottlenecks, but not extend to services, where market works work more or less effectively and high profits reflect the scarcity of specific sites. The single till might distort commercial business in the non-aviation sector.17 Secondly, it proposes a revised regulatory cost base (RRCB) on dual till basis with revaluation of existing assets and returns allowable on future capital reflecting alternative use value. This focuses regulation on a monopolistic bottleneck with prices above single till prices, but below market clearing levels and below forward looking incremental (long run average) costs, thereby increasing incentives to invest. The CAA proposes to set the price cap for current outputs (up to 70 million passengers) on this basis. Thirdly, it proposes a price cap based on the incremental cost of new capacity at Heathrow for a price path beyond 2008 with existing output based on RRCB plus a premium for additional aircraft movements delivered by existing runways. The premium should reflect the difference between the cost of additional output for the airport and the value of additional output for users. Furthermore, contracting between airport and users is recommended, a service quality term should be introduced and enhanced information on capital investment planning should be provided to the airlines (see Andrew and Hendricks, 2002).

This package addresses the central problem of a credible commitment very well. Of course, the current regulator cannot bind the future regulator, but establishing a clear framework clearly signals to the airports that the regulator will leave the airport a fair return on investment for cost effective investments. The whole process is transparent to all parties, strikes a good balance between various interests, and should lead to relatively low transaction costs. It avoids the risk of a fully liberalized system, in which an unregulated monopoly might increase capacity too slowly to reap scarcity rents. It is superior to the German cost-related regulation of investment, where the airlines miss even the basic rights of information on investment programmes given to UK-airport users for years. Adopting such a regulation for German airports would enhance the economic rationality of investment decisions in narrow sense and could be a basis for a rational decision addressing the environmental problem.

Price cap regulation is not a "panacea" (Armstrong et al, 1994, p. 193), but only an imperfect substitute for workable competition. Therefore, it needs to be supplemented by a strategy to promote competition and to decide rationally public policy issues.

There are two options19 to address the problem of investment and externalities. Major projects of airport expansions can be assessed in a public planning process on the basis of benefit-cost analysis. The alternative should be chosen which maximizes social welfare. The second option is to set environmental standards like noise or pollution by politics, which must be met by the airport (cf. Baumol and Oates, 1988). The privatized airport bears the risk of investment. Hamburg's Aviation policy has been increasingly guided by the second option in setting a noise budget (Niemeier, 2000) thereby outperforming other German airports such as Diisseldorf airport in the rational management of environmental issues.

The assessment of the current and future capacity problems of German airports shows that only one of the two German hubs and one of the secondary hubs has excess demand with a rising tendency. Some secondary hubs will have peak problems, but even in the long term the majority of German airports have idle capacity reserves. These unbalances occur under a system in which prices (charges and slot prices) have lost their function to guide traffic to their best uses and to signal when, where and to what extent capacity should be provided. In this environment the airports have adopted a predict and provide strategy to increase capacity whenever future demand might reach capacity limits at peak times. In order to overcome environmental problems they have adopted a strategy of "jobs versus the environment" relying on regional impact studies showing that that airport expansion creates thousands of new jobs. Both strategies are increasingly risky. Increasing capacity well ahead of time is very costly and furthermore, overestimates the negative impact on the environment making the political process more complicated. Investment decisions cannot be based on impact studies20, but only by a benefit-cost analysis. Given these risks a political consensus on airport expansion might not be reached.

The economic and political problems are mainly rooted in the inefficient incentive structure of the regulatory framework. Cost plus regulation sets incentives to an inefficient choice of inputs, which leads to costly airport infrastructure with excess capacity and gold plated terminals, and to an inefficient price structure, which leads to average charges with too low prices for peak demand in order to justify capacity expansion.

As an alternative to cost plus regulation, there are currently three regulatory systems discussed, namely liberalization without ex ante regulation, monitoring and price cap regulation. These systems are evaluated as to whether they might be appropriated to increase the efficiency of the German airport system. Relying only on ex-post regulation will probably lead to a system with monopolistic slack and inefficient price structure as German airports are mostly regional natural monopolies and/or sheltered from competition by law. They face no effective competition and German competition law cannot act a substitute for competition. Monitoring presupposes a creditable threat to regulate the industry if monopoly abuse occurs. While it may be argued that, in Australia, the institutions have gained the necessary experience and knowledge of the industry through price cap regulation, German regulators lack these. The threat to regulate cannot be called credible in Germany. Therefore monitoring might lead to a system as in New Zealand with long lasting litigation and high transaction costs.

The pros and cons of price cap regulation are discussed. As price cap regulation is practised at Hamburg airport it may be easily extended to other airports A truly independent regulator should be implemented who will take care of the technical shortcomings of the Hamburg model, like the asymmetry of the sliding scale. Price cap regulation has the advantage of giving the airports more freedom in their pricing policy than cost plus regulation. Incentives are set for a new price structure and a better use of the existing capacity. As a new price structure with peak pricing creates winners and losers among the airlines, it is very important that price cap regulation passes the productivity gains to airlines and to consumers through a lower level. The combination of an efficient price structure and a lower level of charges might even overcome the resistance of those airlines choosing to fly at peak times. Price cap regulation has the advantage of establishing an efficient price structure with low transactions costs. In the short run, price cap regulation could reduce excess demand and install a price system that signals where and when to expand capacity.

Price cap regulation is supposed to lead to underinvestment, if the regulator cannot credibly promise the airport a fair return on investment. The clear, transparent, and robust approach of investment regulation of the CAA shows that a credible promise can be given.21 Compared to Germany the process is superior as it provides the airlines and the public with more information.

Price cap, far from being a perfect substitute for effective competition, can and should be combined with a variety of measures to promote competition. Slot trading, open skies, privatization with cross ownership controls should be part of a comprehensive reform of the basic rules of the airport industry. Such a reform could lead to a rational management of airport infrastructure with less excess demand and a realistic demand for new capacity. The negative environmental impact would be less than currently forecast, giving the airports an opportunity to engage in a rational discourse on the social cost and benefits of airports' extensions.

In a nutshell, the answer to the question of wheter the German airport industry needs new rules to use and extend capacity efficiently can only be positive. The industry needs less, but effective, regulation with incentives for more competition and for a rational discourse on environmental problems.

The author is grateful to Achim Czerny, Heinz Decker, Ingo Fehrs, Peter Forsyth, David Gillen, Cathal Guiomard, Kai Hüschelrath, Benedikt Mandel, Jürgen Müller, Till Neuscheler, Wilhelm Pfähler and Hartmut Wolf for extensive comments on earlier drafts of the paper. The responsibility for any remaining shortcomings remains the author's.

1 Given the current overcapacity one might argue that the forecast is out of date. I think that this is an open question. On the one hand the forecast is a point forecast of the year 2010 assuming normal conditions. By the year 2010, the crisis might be over and might have not changed the underlying structure of the aviation industry. On the other hand, the rise of low cost carriers and the response of a full service carrier might lead to a market segmentation radically changing the structure of the industry.

2 Düsseldorf with an increase from 36 to 75 movements is an exception as the use of the second runway is assumed, which cannot be used currently due to environmental restrictions.

3 From my point of view this well-behaved function should be interpreted very carefully. Its purpose is more to show how an industry with a functioning price mechanism could work than how it realistically will work. As the function does not take account of the lumpiness character of airport expansions a very important aspect of the airport industry is neglected. With lumpy investment the pattern of prices would fluctuate more (cf. Vickrey, 1971). On the level of the industry the lumpiness of adding capacity at a single airport might be smoothened by the aggregation process if substitutes are available, but this is rather unlikely.

4 Weight-based landing charges are sometimes interpreted as quasi-Ramsey prices because heavier aircraft are able to pay a higher charge than small aircraft (Productivity Commission, 2002). This interpretation is correct, although the system has its shortcomings and can probably never be designed in a perfect way, as the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC, 2001) points out. The important thing is that, as Morrison (1982) shows, the approximation can be improved easily.

5 Figure 12.8 shows an efficient allocation of slot capacity. However, the current slot distribution rules have the danger of reducing welfare (Starkie, 1998). If the historically determined initial distribution of slots prevails because of institutional obstacles, the demand might be suppressed by inefficient carriers.

6 Compared with network airlines, charter airlines use larger aircraft with narrow seating and high load factors. The rise of low-cost airlines was not foreseen in 1995.

7 The mediation process also overlooks that the results have a bias towards full expansion and that the induced effects which amount to at least a fifth of the total effects are independent of the decision to expand capacity at Frankfurt Airport (Niemeier, 2001).

8 Public ownership has obviously also a major impact on the performance as very often airports are seen as a tool of regional policy. Airports should increase local employment. Terminals are seen as highlighting the dynamism of a city. No doubt even for commercially run airports these factors are important as long as the owners remain the local government.

9 Ex-ante regulation is commonly justified by a combination of economies scale and scope and sunk costs relative to demand. A different reasoning is that even if scale economies have been exhausted, it may not be possible to build additional airports for environmental reasons. Thus, airports have a locational monopoly.

10 Of course, this is just a rough estimation. What is necessary is an industry analysis taking into account also the competition of other transport modes. The multi modal approach by Mandel (1997) for Northern Germany could be extended for German airports including the competition from other European airports.

11 While the Productivity Commission finds "an incentive for airports to temper prices for aeronautical services" (2002, p. 188) the Network Economics Consulting Group on behalf of the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission concludes that the price elasticity for aeronautical services is rather too low to temper prices (ACCC, 2001).

12 For a more critical assessment compare Forsyth (2002). So far, monitoring is a rather loosely defined concept. Therefore, a possible outcome might be a system similar to cost plus regulation as Forsyth argues.

13 On the problem of productive inefficiency see Niemeier (2002).

14 in the dynamic setting strategic behavior might induce the regulated firm to have relative high costs at the end of the review period so that the potential of the increase of productivity is hidden from the regulator (Bös, 1991).

15 Of course, an efficient price structure on a too high level due to productive inefficiency is still an inefficient outcome in the strict sense of Pareto. However, we are here aiming at something very pragmatic, namely some price differentiation and some decrease in the price level.

16 Lieb-Doczy and Shuttleworth (2002) name three examples for a hold up problem between regulator and private firm, but Ai and Sappington (2001) found that aggregate investment of US telecommunications does not vary systematically under incentive regulation reiativel to rate-of return regulation.

17 For an extensive discussions of the pro and cons of the single till principle see "The Single Till Approach to the Price Regulation of Airports" by Starkie and Yarrow (2000) Surprisingly the Competition Commission finds the "arguments and current evidence for moving to the dual till ... not persuasive" (CAA, Press Release, 13 August 2002).

18 Economic and environmental regulation are analytically two separate issues. Having said that, it is important to address both problems as even the best incentives to invest by good economic regulation cannot overcome blockades of investment projects due to environmental restrictions.

19 There is also the option of voluntary agreements between the airport and it's neighbours along the lines developed by the Coase and Buchanan school. However, because of the public good character of externalities, the greater the numbers affected by airport pollution the lower the probability to reach efficient solutions (cf. Frank, 1983 p. 288).

20 Impact studies tend to exaggerate the effects on economic activity and do not provide measures of benefits.

21 Of course, the creditability depends also on future regulators.

Ai, C. and Sappington, D.E. (2001) The Impact of State Incentive Regulation on the U.S. Telecommunications Industry, http://bear.cba.ufl.edu/sappington/papers/itxt4.pdf.

Andrew, D. and Hendriks, N. (2002) Price cap regulation of airports in the UK, Paper presented at the German Aviation Research Seminar, "The Economic Regulation of Airports: Recent Developments in Australia, North America and Europe, November 8-9, Bremen.

Armstrong, M., Cowan, S. and Vickers J. (1994) Regulatory Reform: Economic Analysis and British Experience, Cambridge Mass, MIT Press.

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2001) Price Regulation of Airport Services, Submission to the Productivity Commission's draft Report October 2001, www.pc.gov.au.

Baumol, W.J. and Oates, W.E. (1988) The Theory of Environmental Policy, 2nd edition, Cambridge University Press.

Bös, D. (1991) Privatization, A Theoretical Treatment, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Bös, D. (2001) Regulation: Theory and Concepts, Bonn http://www.wiwi.unibonn.de/users/fiwi/www/papers/pps/ppslist.htm.

Bradley, I. and Price, C. (1988) The economic regulation of private industries by price constraints, Journal of Industrial Economics, Vol. 37, pp. 99-106.

Brunekreeft, G. (1998) Price capping and peak-load pricing in network industries, Discussion Paper No. 73, University of Freiburg.

Bulwien, H., Hujer, R. Kokot, S., Mehlinger, C., Rürup, B., Voßkamp, T. (1999) Einkommens- und Beschäftigungseffekte des Flughafens Frankfurt/Main, Frankfurt.

Button, K.and Stough, R. (2000) Air Transport Networks, Edward Elger Cheltenham.

CAA (2002) Competition Commission Current Thinking on Dual Till - CAA statement on process Press Release, 13 August 2002, London, www.caa.co.uk.

CAA (2001) Heathrow, Gatwick, Stansted and Manchester Airports Price Caps 2003-2008: CAA Preliminary Proposals - Consultation Paper, London, www.caa.co.uk.

Commonwealth Treasurer (2002) Productivity Commission Report on Airport Price Regulation, Joint Press Release Minister for Transport & Regional Services and Treasurer, www.treasurer.gov.au/tsr/content/pressreleases/2002/024

Costa, P.R., Hamed, D.S. And Lundquist, J.T. (2002) Rethinking the aviation industry, McKninsey Quarterly, 2002, number 2, www.mckinseyquarterly.com/article.

Doganis, R. (1992) The Airport Business, London, Routledge

Ewers, H.-J., Tegner, H., Joerss, I., Eckhardt, C. F., Jacubowski, P., Meyer, C.A., Brenck, A. and Czerny, A. (2001) Possibilities for the Better Use of Airports Slots in Germany and the EU, Berlin, TU-Berlin.

Forsyth, P. (1977) Price Regulation of Airports: Principles with Australian Applications, Transportation Research-E, Vol. 33, No 4, 297-309.

Forsyth, P. (2001) Airport Price Regulation: Rationales, Issues and Directions for Reform, Submission to the Productivity Commission Inquiry: Price Regulation of Airport Services, Department of Economics Discussion Paper 19/02, Monash University Clayton.

Forsyth, P. (2002) Replacing Regulation: Airport Price Monitoring in Australia, Paper presented at the German Aviation Research Seminar, "The Economic Regulation of Airports: Recent Developments in Australia, North America and Europe, November 8-9, Bremen.

Flughafen Hamburg GmbH (1996) Antrag der Flughafen Hamburg GmbH auf Planfeststellungsbeschluss gemäß 8 Abs, I LuftVG für die Änderung des Flughafens Hamburg durch Errichtung und Betrieb eines Vorfeldes 2 nebst damit im Zusammenhang stehenden und im Antrag konkretisierten Maßnahmen und durch eine neue Lärmschutzhalle vom 23. Dezember 1996, Hamburg.

Fridström, L. et al. (2002) Competitive Airlines: Towards a more Competitive Policy in Relation to the Air Travel Market, Report from the Nordic Competition Authorities, Copenhagen, Helsinki, Oslo, Stockholm, www.konkurransetilsynet.no/archive/internett/publikasjoner/nordisk_rapport/nordic_report_competitive_airlines_01_02.pdf.

Frank, J. (1983) Markt versus Staat. Zur Kritik einer Chicago-Doktrin, in Jahrbuch Ökonomie und Gesellschaflt, Vol. 1, pp. 257-298, Frankfurt.

Gillen, D., Hinsch, H., Mandel, B., and Wolf, H., (2000), The Impact of Liberalizing International Aviation Bilaterals on the Northern German Region, Ashgate.

Gillen, D., Henriksson, L. and Morrison, W. (2001), Airport Financing, Costing, Pricing and Performance in Canada, Final Report to the Canadian Transportation Act Review Committee, Waterloo.

Giulietti, M. and Waddams Price, C. (2000) Incentive Regulation and Efficient Pricing: Empirical Evidence, Research Paper Series No. 00/2 Centre for Management under Regulation Warwick Business School.

Graham, A. (2001) Managing Airports, An International Perspective, Butterworth Heinemann, Oxford.

Helm, D. and Thompson, D. (1991) Privatised Transport Infrastructure and Incentives to Invest, Journal of Transport Economics and Policy, 25(3), pp. 231.246.

Hujer, R, and Kokot, S. (2001) Frankfurt Airport's impact on regional and national employment and income, in W. Pfähler (ed.), Regional Input-Output Analysis, Baden-Baden, Nomos Verlag.

Kunz, M. (1999) Airport Regulation: The Policy Framework, in: Pfähler, W., Niemeier, H.-M. and Mayer (Eds.), O. Airports and Air Traffic - Regulation, Privatisation and Competition, Peter Lang Verlag: Frankfurt New York, pp. 11-55.

Kunz, M. (2000) Regulierungsregime in Theorie und Praxis, in: Knieps, G./Brunekreeft, G. (Eds.) Zwischen Regulierung und Wettbewerb Netzsektoren in Deutschland, Heidelberg, Physica.

Landgericht Düsseldorf (2001) Urteil in dem Rechtsstreit der Flughafen Düsseldorf GmbH gegen Hapag-Lloyd Fluggesellschaft mbH vom 20.6.01, 34 0 (Kart) 36/01 Düsseldorf.

Levine, M.E. (1969) Landing fees and the Airport Congestion Problem, Journal of Law and Economics, 12, pp.79-109.

Lieb-Doczy E. and Shuttleworth G. (2002) Grundprinzipien eines wirtschaftlich effizienten regulatorischen Prozesses, London, www.nera.com.

Mandel, B. (1997) Luftverkehrsprognose für den Flughafen Hamburg, Untersuchung von MKmetric im Auftrag der Wirtschaftsbehörde der Freien und Hansestadt Hamburg, Hamburg.

Marshall, A. (1890/1920) Principles of Economics, 1st edition 1890, 8th edition 1920, London, Macmillan.

Mediationsgruppe Flughafen Frankfurt (2000) Bericht Flughafen Frankfurt/Main, Frankfurt.

Morrison, S.A. (1982) The Structure of Landing Fees at Uncongested Airports, Journal of Transport Economics and Policy 16, pp. 151-159.

Niemeier, H.-M. (2000) Towards an efficient market-based environmental policy a view form the Hamburg Region, in Immelmann, T., Mayer, O. G., Niemeier, H.M., Pfähler, W., (editors), Aviation versus Environment?, Frankfurt M., New York, Peter Lang Verlag.

Niemeier, H.-M. (2001) On the use and abuse of Impact Analysis for airports: A critical view from the perspective of regional policy, in W. Pfähler (ed.), Regional Input-Output Analysis, Baden-Baden, Nomos Verlag.

Niemeier, H.-M. (2002) Regulation of Airports: The Case of Hamburg Airport - a View from the Perspective of Regional Policy, Journal of Air Transport Management, Vol. 8, pp. 37-48.

Niemeier, H.-M. and Wolf, H. (2002) Strategische Allianzen zwischen Flughäfen notwendiges Gegengewicht zur Blockbildung der Fluggesellschaftten? in Knorr, A., Europäischer Luftverkehr - wem nutzen die strategischen Allianzen?, Schriftenreihe der DVWG, B 246 Bergisch-Gladbach.

New Zealand Commerce Commission (2002) Final Report. Part IV Inquiry into Airfield Services at Auckland, Wellington and Christchurch International Airports, August.

Pels, E. (2000) Airport Economics and Policy Efficiency, Competition and Interaction with Airlines, Tinbergen Research Series 222, Netherlands.

Productivity Commission (2002) Price Regulation of Airport Services; Report No 19, Auslnfo, Canberra.

Sherman, R. (1989) The Regulation of Monopoly, Cambridge UK, Cambridge University Press.

Soltwedel, R. and Wolf, H. (1996), Privatisierung öffentlicher Unternehmen Eine ordnungspolitsche Reflexion, in: DVWG (editor), Privatisierung deutscher Flughäfen, Bergisch Gladbach, pp. 4-20.

Starkie, D. (1998) Allocating Airport Slots: A Role for the Market, Journal of Air Transport Management, Vol. 4, pp. 111-116.

Starkie, D. (2001) Reforming UK Airport Regulation, Journal of Transport Economics and Policy, 35, 119-135.

Starkie, D and Thompson, D. (1985) Privatising London's Airports, Institute for Fiscal Studies, Report 16, London.

Starkie, D. and Yarrow (2000), The Single Till Approach to the Price Regulation of Airports, London, www.caa.co.uk.

Urbatzka, E., Focke, H,, Stader, A. and Wilken, D. (1999) Szenarien des Luftverkehrs im Jahr 2010 vor dem Hintergrund kapazitätsbeengter Flughafeninfrastruktur, Forschungsbericht 43, Deutsches Zentrum für Luft-und Raumfahrt, Koln.

Viner, J (1931) Cost curves and supply curves, Zeitschrift für Nationalökonomie, Vol. 3, pp. 23-46.

Vickers, J. and Yarrow, G. (1988) Privatization, An Economics Analysis, MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass.

Vickrey, W. (1971), Responsive pricing of public utility services, Bell Journal of Economics, 2, pp. 337-46.

Williamson, O.E. (1985) The Economic Institutions of Capitalism, Free Press, New York.

Wolf, H. (1997) Grundsatzfragen einer Flughafenprivatisierung in Deutschland, Kiel.