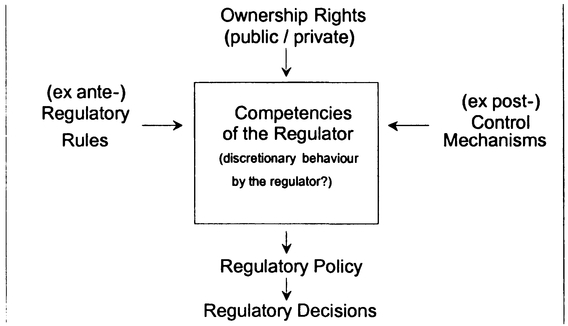

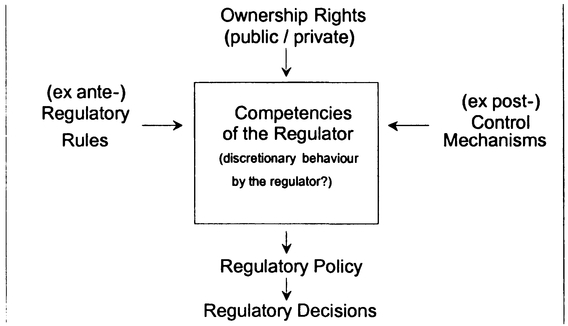

Figure 14.1 Elements of a regulatory system

Source: Wolf (2003)

Hartmut Wolf

Airport privatisation has been - and still is - on the agenda of national air transport policies of many countries throughout the world. Privatisation may take many different avenues, ranging from only a minor divestiture of airport companies by public shareholders (for example in Germany) to a complete sell-off of (former) public airports to private investors (for example in Australia). Privatisation can be restricted to the operation of public infrastructure facilities by a private firm (for example in Bolivia), or it can also involve privatising the airport's infrastructure (for example in the UK). As infrastructure facilities of airports are usually regarded to be non-contestable monopolies, privatisation is typically accompanied by some form of price regulation.1

The regulation may take a variety of forms, ranging from strict rate-of-return to price-cap regulation (with various sliding scale mechanisms in between).2 It may be restricted to the airside activities of airports (for example Hamburg Airport), or it may also cover non-airside activities (for example in the UK). Not least, airports can be privatised while all markets for airport services are fully deregulated (as in New Zealand). Against this variety of institutional settings that govern the airport sector, policy makers might ask what form of privatisation, and what design of the institutional setting within which privatised airports will have to operate, will prove to be most adequate to ensure efficient operation of privatised airports.

This chapter analyses the determinants of the appropriate design of ownership structures in the airport sector and of the institutional setting for airport service markets. The analysis is based on The New Institutional Economics.3 This paradigm focuses on asymmetric information and incomplete contracts and the institutions that govern these contracts. Contracting parties are aware of the dangers of opportunism that might emerge because of informational asymmetries and the incompleteness of contracts, and they design governance structures to protect their own quasi-rents against opportunism by their respective partners. A governance structure is efficient if it minimises transaction costs, the latter comprising the operating costs as well as the incentive costs that are generated by that structure. The efficient design depends on the specific characteristics of the transaction in question. The main dimensions are the asset specificity of supporting investments and the frequency of transaction. Asset specificity refers to the dedication of investments to specific uses and/or transaction partners (for example complex baggage systems for hub and spoke carriers represent highly specific assets while land - although it is immobile - generally does not). Thus, a high degree of asset specificity makes the economic value of that investment highly dependent on the transaction in question and hence locks the investor into that transaction.

The chapter is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the choice of airport ownership structures and the design of airport regulation as a contract problem. Section 3 evaluates alternative governance structures and identifies complementarities between the distribution of ownership rights and the design of the institutional setting within which privatised airports operate. Within section 4, some general guidelines on how to appropriately design airport privatisation policy will be derived from the results achieved so far. Finally, the overall results of this chapter will be summarised in section 5.

Following Goldberg (1976), the distribution of ownership rights to airports and the design of price regulation can be analysed as a contract problem. As he argued, regulation may generally be viewed as a transaction cost saving device for controlling the behaviour of natural monopolies in cases where transaction-specific investments lead to non-contestability of monopoly markets while at the same time locking the seller's investments into that transaction.4 Hence, it is not only the buyer of the natural monopolist's services that needs to be protected against opportunism by the seller (i.e. monopoly pricing), but also the seller needs security of expectations, otherwise she would not invest specifically in that transaction. Regulation as a governance structure has to protect both parties' reasonable interests, otherwise inefficient outcomes will occur.

As regards the airport sector, aprons, runways, and - to lesser degree - also terminals represent immobile investments dedicated for specific uses and with long working lives. Once these investments have been made, the future economic fate of a regulated airport is bound to future decisions by the regulator. On the other hand, the social welfare effects of airport regulation depend on the willingness of airport authorities to invest in such facilities. Because airport infrastructure is often a regional non contestable monopoly, the regulator (as an agent for the airports' users and regions) is typically tied within bilateral relationships with the airport authorities. Hence, both sides (i.e. airport authorities and the regulator) need protection against opportunism by the respective partner either by self-insuring or self-action or by a third party.

If all transaction-specific investments were dividable into fairly small steps the regulatory risk of an airport authority would be minimal. She could employ a trigger strategy realising her planned investment step by step, making her particular next step depend on the regulator's past decisions. As long as the regulator is interested in ongoing investment the airport authority may exercise a threat of not realizing the next step of investment if the regulator behaves opportunistically by exploiting the airport's quasi-rents. Also, the regulator could retaliate for opportunistic behaviour by the airport by lowering the level of airport charges below long run marginal costs. Both threats would make the regulatory contract self-enforcable without collateral institutional safeguards (Salant and Woroch 1991). However, in reality expanding major infrastructure facilities has to be done in large discrete steps, which seriously restricts the ability of airport authorities to retaliate to an opportunistic regulatory policy once these investments have been realized. Because indivisibilities in airport infrastructure investments prevent self-enforcement of regulatory contracts without institutional safeguards against opportunism, appropriate governance structures have to be implemented.

Airport regulation means that the task of controlling the behaviour of the airport company is not performed by the users of that airport, but by a regulator, who simultaneously acts as a principal for the regulated airport and as an agent for the airport users. Asymmetric information and bounded rationality prevent perfect (i.e. in the sense of neoclassical economics: first best welfare maximising) regulatory outcomes. Instead, dangers of opportunism might exist. In this respect, opportunism may come in three ways. First, informational disadvantages of the regulator about the real conditions of production for the airport might lead to opportunistic behaviour by the airport company, which would result in allocative and/or productive inefficiency.5 Second, transaction-specific investments create a lock-in effect for the airport company which might give the regulator ex post-opportunities to expropriate the firm's quasi-rents. And third, as the results of price regulation usually affect all airport's users regardless of their individual efforts to control the regulator, their control efforts might be socially suboptimal,6 which provides the regulator with opportunities to behave opportunistically against the users' interests.7 To achieve efficient outcomes of airport privatisation, the governance structure that defines the relationship between airport company, regulator, and airport users has to be designed carefully to protect the reasonable interests of airport companies and airport users. In this sense, the design of airport privatisation policy does not only mean a change in the ownership structures in the airport industry, but to design an institutional setting for the airport sector that guarantees the maximum of social welfare gains that can be realised by privatisation.

Williamson (1986: 112 pp.) generally identifies four prototypes of governance structures, namely (1) market governance, (2) trilateral governance (neoclassical contracting), (3) transaction-specific governance (relational contracting), and (4) unified governance (internal organisation). Market governance is the main governance structure for non-specific transactions of both occasional and recurrent contracting. Such transactions do not need institutional safeguards against opportunism, as all transacting parties have outside options for their investments and hence have the opportunity to end the transaction without incurring sunk costs. Buyers can easily turn to alternative sources, and suppliers can sell output intended for one order to other buyers without difficulty. Ground handling fits into that kind of transaction, as buses and cargo loaders can easily be transferred between different airports and customers. These costless exit options prevent opportunism. A trilateral governance structure means that the contracting partners choose an independent institution as an arbitrator for conflict resolution, for example the legal system and its courts may act as an arbitrator. However, a precondition for an effective trilateral governance structure, i.e. a governance structure that effectively protects the contractors' quasi-rents, is a regulatory contract that is either almost complete or entails unambigous conflict resolution mechanisms, so that the arbitrator is able clearly to detect contract breeching and to identify clearly the party that has breached the contract. Transaction-specific governance means that the contractors do not rely on conflict resolution by an independent arbitrator, but instead agree on self-enforcing contracts that protect each other's quasi-rents. A contract is self-enforcing if the partners supply hostages to each other in order to commit to ongoing contractual relationships (Williamson 1983). Finally, a unified governance structure means vertical integration between the contractors. Vertical integration eliminates the danger of losing quasi-rents as a result of opportunistic behaviour by the partner. However, agency problems within the unified governance structure might occur, as vertical integration eliminates the disciplinary exit option of market governance.

In the airport sector, and with respect to privatisation, leaving transactions solely to the market would mean total privatisation without any regulation. This would avoid dangers of opportunistic behaviour by a regulator and related under-investment by the airports. Markets for ground handling are highly contestable, hence markets are appropriate institutions for governing transactions in handling services. Infrastructure facilities, however, may be non-contestable monopolies in their location. If so, the regions that are served by these facilities depend on the behaviour of the monopoly supplier of infrastructure services. It might be expected that unregulated airports with strong market power would raise the level of infrastructure charges well above long run marginal costs in order to reap monopoly profits. It has been argued in the literature, however, that this should cause no concern with regard to efficiency considerations, as airports could engage in almost perfect price discrimination. Perfect price discrimination would lead to the production of the maximum of output of infrastructure services that cover its costs. Hence, reaping monopoly rents by unregulated airports would only generate a fairly small welfare loss in terms of allocative efficiency while the airports would have all incentives to produce efficiently. In particular, regulation-induced over-capitalisation (or under-investment), X-inefficiency and costly rent seeking behaviour by the airports in a regulatory process would be avoided. That would probably overcompensate for the small loss of allocative efficiency that has to be expected (Forsyth 2002: 21).

Figure 14.1 Elements of a regulatory system

Source: Wolf (2003)

Note, however, that full deregulation of the markets for infrastructure services does not automatically mean that the economic behaviour of airports is not subject to control by state authorities. Instead, even the services of a fully privatised airport are typically supervised by a national competition authority on the grounds of common competition law. Further, recall the lumpy character of the airport's investments in major infrastructure facilities, which means that differentiation of airport charges according to the price elasticities of different markets lies at the heart of the problem of ensuring efficient usage of the infrastructure facilities. In contrast, common competition law is often not suited to encourage efficient price differentiation. For this reason, competition authorities might refuse efficient differentiation of airport charges.8 Hence, it might be doubtful if almost perfect price discrimination would occur after the markets for airport infrastructure services had been fully deregulated. Therefore, political reliance on the functioning of fully deregulated markets for infrastructure services may generate high social costs. If common competition law in the country under consideration is not suited to allow for perfect price discrimination, it might be wise to install another governance structure, i.e. either an internal, a trilateral, or a transaction-specific one.

Accordingly, airport regulation may come in three ways (Figure 14.1). First, regulation may be performed by means of internal regulation, which means that the state as owner of an airport company exercises ownership rights to control the behaviour of the company by internal command. With respect to airport privatisation, a precondition for internal regulation is only partial divestiture of airport companies by public owners. Internal regulation eliminates the regulatory risk to the airport company (because expropriation of the airports' quasi-rents by an opportunistic regulatory policy that sets the level of charges below long run marginal costs would harm the regulator herself) and hence avoids related problems of under-investment in specific airport facilities. In effect, such a structure provides a set of incentives that leads the airport to superior if not optimal investment decisions. However, public ownership probably leads to inefficient outcomes for political-economic reasons: the regulatory process is likely to be influenced by pressure groups and self-interested politicians and hence by political considerations that might not be in the interests of the airport's users. Without going into political-economic details here why - and if always - public ownership is likely to generate considerable inefficiencies9 it might be noticeable that airport privatisation is often justified as a means to improve the efficiency of airport services by altering incentives for the airport's management. Obviously, as incentive structures of an airport's management are shaped by the objectives of owners, expectations about improved efficiencies of privatised airports must rest on the assumption that privatisation leads to a depoliticisation of the regulatory process. That is only credible if state authorities cannot influence the airport's management decisions by internal regulation, i.e. if full privatisation (or at least a major divestiture of public airports) takes place.

Alternatively, and second, regulation can be strictly bound to ex ante-specified rules which are enforceable before courts, thus leaving the regulator no discretion. Such rules would effectively protect the airport company's quasi-rents and thus would facilitate complete airport privatisation without inducing problems of under-investment. However, while eliminating the dangers of opportunism by the regulator, such governance structure might give airports the opportunity to behave opportunistically, as such rules are unavoidable inflexible. For example the well known rate of return-regulatory mechanism, that guarantees the airport company a fair and reasonable rate-of-return on employed capital whatever its costs, represents such a rule, which eliminates the (otherwise existing) hold-up problem of the airport operator, but also gives the company incentives for over-capitalisation (Averch and Johnson 1962). Furthermore, ex ante-rules make regulation heavy handed because the rules must be tailored to control for all action parameters of the airports, otherwise price regulation could be easily undermined by non-pricing strategies of the airport operators. For example a fixed price-cap gives the airport incentives to lower the quality of its services in order to circumvent regulatory restrictions unless rules are implemented that explicitly control for service quality. A rate-of-return mechanism gives the airport incentives to set an inefficient structure of charges in order to create additional demand at peak times (which can be used to justify the building of additional airport capacity) unless the structure of charges becomes subject to regulatory control (Bailey and White 1974). All in all it is very doubtful if regulating a private airport by strictly defined ex ante rules leads to better results in terms of social welfare than internal regulation by means of public ownership. Indeed, as Vickers and Yarrow (1988: 40) conclude after examining the results of empirical studies about the relative performance of private and public companies, private companies that are heavily regulated tend not to perform better than public ones.

Inflexible and heavy handed regulation may be avoided by allowing for discretion by the regulator, especially by giving her the opportunity to sanction opportunistic behaviour by the airport by lowering charges ex post, thus making regulation a repeated game between the airport and the regulator. This might probably reduce incentives of the airport to exploit informational advantages from the beginning, which in turn reduces the need for continously ex ante control of all action parameters of the company. For example regulatory discretion would enable the regulator to lower price-caps if she detects quality dumping by the airport, thus weakening the airport's incentives to lower the quality of her services, and, hence, making ex ante specification of quality standards by inflexible rules avoidable. However, a precondition for efficient outcomes of a discretionary policy is again the existence of institutional safeguards that protect the airport's quasi rents. Otherwise, regulation may fail to achieve efficient infrastructure investments by the airport.

These considerations lead to the third prototype of regulatory governance, namely ex post control of regulatory outcomes. Implementing a governance structure that relies heavily on ex post control mechanisms means giving the regulator freedom to skim monopoly rents from the airport ex post by lowering charges below long run marginal costs for a while. At the same time, they can protect the airport's quasi-rents by exerting a threat of sanctions on the regulator if regulatory outcomes prove to be inefficient. The idea is to make regulation more light handed by designing a relational regulatory contract that is self-enforceable.

The self-enforcement of relational contracts, as we have stated, needs collateral that each of the contractors provide to their counterparts. The investments by the airport in major infrastructure facilities represents such collateral, as such investments bind its economic fate to the future decisions of the regulator. For the part of the regulator, her competencies to regulate may represent an effective hostage that might protect the airport's quasi-rents. Hence, protection can be provided by the threat of the regulator losing her capability. To make this threat credible, regulatory outcomes have to be controlled by an independent institution that is allowed to stop regulation, but even this control institution might behave opportunistically. Therefore, guidelines are needed as to what constitutes inefficient outcomes of regulation. In order to preserve flexibility in the system, these guidelines necessarily have to be somewhat vague. A further safeguard could be a division of competencies between different institutions (a) of assessing the efficiency of regulatory outcomes and (b) of deciding about the future of regulation. If so, those institutions that are commissioned to detect inefficient regulatory outcomes would not profit from the abolition of regulation. This would probably reduce the incentives to cheat. To sum up, a precondition for improving the efficiency of regulation is the implementation of a system of checks and balances with various institutions involved.

However, such an institutional setting remains to represent an incomplete contract with only vague guidelines on what constitutes inefficient regulatory outcomes. Hence, it would be wise to install additional elements into the system that may serve as safeguards to protect the airport against unduly regulatory decisions. Appropriate safeguards may be (a) the abolition of the single till principle, which would mean that the airport's revenue from non-airside activities is shielded from misbehaviour by the regulator, and (b) delegating the task of regulating designated airports to an institution that is responsible for regulation of all airports that are subject to regulation (or even also of other regulated industries like electricity, gas, and telecommunications). If so, the regulator has to take into account the effects of her decisions regarding one particular airport on the whole airport system (respectively on the system of all regulated industries). Note, that different airports will realise their investments at different times. Therefore, exploitation of one airport's past investments in immobile assets by the regulator would harm this airport, but would also probably lead to the unwillingness of other airports to further invest in major infrastructure facilities. Hence, the responsibility for the whole airport system would defuse the problem of indivisibilities of infrastructure investments, which lies at the heart of the credibility problem.

Although the introduction of a regulatory system that heavily relies on ex post control mechanisms may improve the efficiency of regulatory outcomes, the building and operation of the needed institutions comes not without costs. These costs may probably be higher than maintaining public ownership or designing a set of strict ex ante rules. They must be weighted against the expected improvements in efficiency through regulation by ex post controls. It may be expected that these costs will become smaller compared to the benefits of such a system the more airports will become subject to ex post control under a unified legal framework, as the operation of the needed institutions is likely to be characterised by economies of density. In contrast, it can be expected that the smaller the number of airports that will become subject to privatisation, the less attractive is the introduction of effective ex post-control mechanisms. Thus, the building and operation of an institutional setting that heavily relies on ex post controls is more attractive, the more airports that operate under that setting.

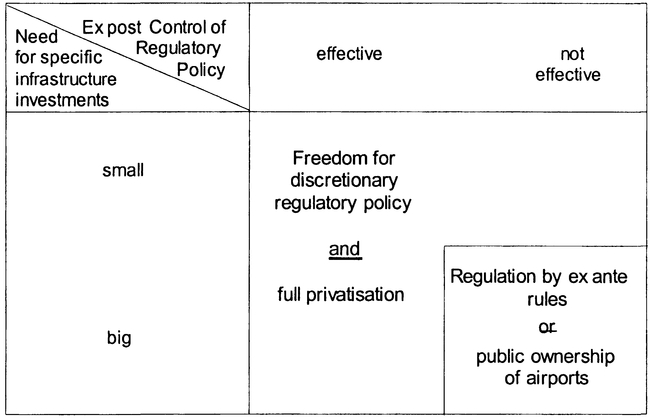

The discussion so far leads us to the following results with regard to the appropriate design of privatisation policy for the airport sector. First, complementarities exist between the optimal choice of the form of privatisation and the design of the legal framework within which privatised airports will operate. Full privatisation is only feasible if the institutional framework guarantees effective protection of the airports' quasi-rents (Figure 14.2). Otherwise airport privatisation has to be restricted to a minor divestiture of public airport companies or to the operation of public infrastructure facilities by a private contractor. The latter would mean that the state would be responsible for infrastructure investments.

Second, if the governance structure ensures effective ex-post control of regulatory policy, inflexible ex ante-regulatory rules can be avoided, and regulatory policy could be more light handed than if it is based on such rules. Hence, light handed regulation needs strong institutions that interact within a system of checks and balances.

Finally, the building of ex post control-mechanisms will be especially suitable in countries that had privatised (or plan to privatise) not only a single but a greater number of airports.

Figure 14.2 Governance structures in the airport industry: Complementarities

Source: Wolf (2003).

The following guidelines for the appropriate design of an airport privatisation policy that aims at enhancing the efficiency of the airport sector may be derived from the results achieved so far.

The discussion in the preceding sections has shown that complementarities exist between the legal framework for the airport sector and the privatisation strategy of public owners. Designing privatisation policy means deciding simultaneously on the airports' ownership structures as well as on the legal framework that cover the airport sector. Privatisation will only lead to improved efficiency of airport services if it is accompanied by full deregulation of the airport sector or - if full deregulation is not feasible - by implementing a governance structure that allows for light handed regulation. However, light handed regulation needs strong institutions that may act discretionally, and discretion needs to be supervised, otherwise inefficient outcomes will occur.

1 A noticeable exemption is New Zealand, which privatised its major airports without any accompanying price regulation.

2 The new airport at Athens may serve as an example for the application of rate-of-return regulation, the BAA airports in the UK may serve as examples for airports that are regulated by a price-cap regime, and the airside charges of Vienna Airport are subject to a sliding scale mechanism.

3 For an overview see Richter and Furubotn (1996).

4 See also Williamson (1976).

5 Productive inefficiency is likely to occur if the airport company cannot fully transform rents into profits for her shareholders because the regulator would tax that profit away. Then she may have incentives to transform potential profits into rents for the insiders within the firm (X-inefficiency) as it is much more difficult for the regulator to detect and expropriate insider-rents than profits.

6 Any Airport user is affected by the results of regulation regardless of the individual efforts to control the regulator.

7 Regulatory capture (i.e. the regulator identifies herself with, and pursues the aims of the regulated firm against the airport's users' interests) fits into this type of opportunistic behaviour.

8 In some countries (for example in Germany) decisions by the national competition authorities against anti-competitive behaviour may be challenged by the offenders before courts, which could overrule the competition authorities' orders. The effect on the efficiency of market outcomes might be twofold: on the one side such a governance structure might protect the suppliers' quasi-rents against opportunistic orders by the competition authorities. On the other side, it might lead to a tendency by competition authorities to base their orders against monopolistic misbehaviour on considerations with regard to the suppliers' costs or on a comparison with a particular supplier's prices in different markets on which the supplier operates (which can be clearly seen for example from the historic track record of the German competition authority). In this way, the competition authorities might try to base their decisions on objective and clear criteria in order to avoid overruling of their orders by the courts, which could, however, reduce the firms' incentives to enhance productive efficiency.

9 There exists a considerable body of literature on this subject that suggests that public ownership is not in itself going to generate inefficiencies but incentives and broader public mandates can explain some of the inefficiencies. Thus, giving the same incentives to public managers should lead to the same results as in the private sector. For an overview see for example Vickers and Yarrow (1988: 11) and Brenck (1993: 56).

Averch, H. and L.L. Johnson (1962) Behaviour of the Finn under Regulatory Constraint. American Economic Review 52 (5): 1052-1069.

Bailey, E.E. and L.J. White (1974). Reversals in Peak- and Off-Peak Prices. Bell Journal of Economics 5 (1): 75-92.

Brenck, A. (1993) Privatisierungsmodelle für die Deutsche Bundesbahn. In W. Allemeyer, A. Brenck, P. Wittenbrinck and F. v. Stackelberg (Eds.), Privatisierung des Schienenverkehrs. Vandenhoek & Ruprecht, Göttingen.

Forsyth, P. (2002) Privatisation and Regulation of Australian and New Zealand Airports. Journal of Air Transport Management 8 (1): 19-28.

Goldberg, V.P. (1976). Regulation and Administered Contracts. Bell Journal of Economics 7 (2): 426-452.

Richter, R., und E. Furubotn (1996) Neue Institutionenökonomik. Eine Einführung und kritische Würdigung. Mohr, Tübingen.

Salant, D.J. and G.A. Woroch (1991) Crossing Dupuit's Bridge Again: A Trigger Policy for Efficient Investment in Infrastructure. Contemporary Policy Issues 9(2): 101-114.

Vickers, J. und G. Yarrow (1988) Privatisation: An Economic Analysis. MIT-Press, Cambridge, Mass.

Williamson, O.E. (1976) Franchise Bidding for Natural Monopoly in General and with Respect to CATV. The Bell Journal of Economics 7 (1): 73-104.

Williamson, O.E. (1983) Credible Commitments: Using Hostages to Support Exchange. American Economic Review 73 (4): 519-540.

Williamson, O.E. (1986) Economic Organization. Firms, Markets and Policy Control. Wheatsheaf, Brighton, Sussex.

Wolf, H. (2003) Privatisierungspolitik im Flughafensektor. Eine ordnungspolitische Analyse, Springer, Heildelberg.